A Scoping Review of the Factor Associated with Older Adults’ Mobility Barriers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Question

2.2. Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

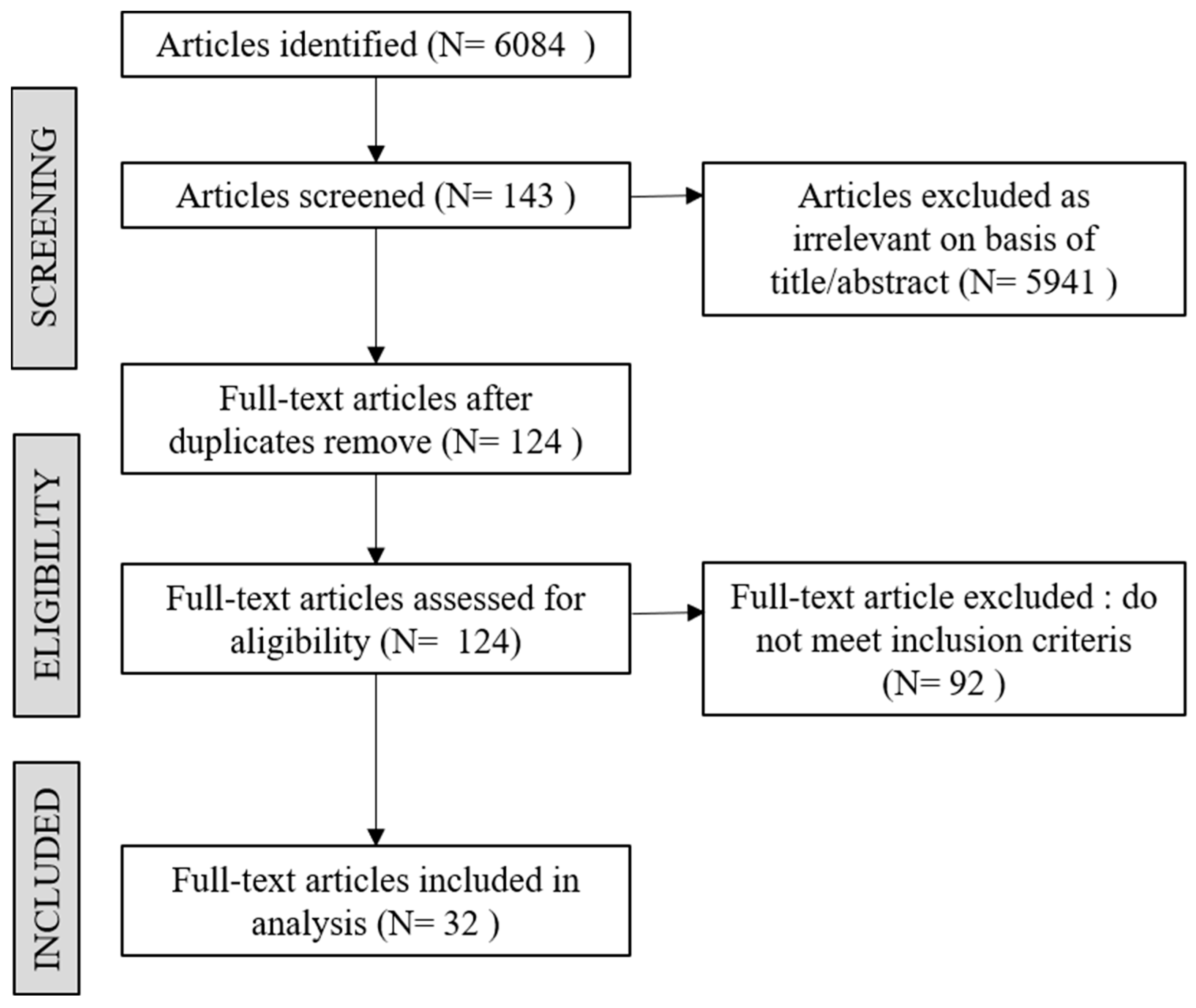

2.3. Screening

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Health, Disabilities and Fear of Falling

3.2. Build Environment

| Author | Country/Setting | Objective | Design/Method | Sample Size | Characteristics | Analysis Method | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nordbakke and Schwanen 2015 [11] | Norway | To investigate the relationship between transportation and well-being by examining the extent to which older adults believed their needs for outdoor activity participation were unsatisfied. | Survey | 4712 | Aged 67 and above | SPSS | The level of unmet needs for out-of-home activities was shaped by transportation-related factors, such as having a driver’s license and subjective evaluations of public transportation supply. Actual participation in out-of-home activities, self-perceived health, and walking problems, outlook on life, residential location, and indicators of social support and networks, also explained differences in the extent of unmet activity needs. |

| Rantakokko et al. 2017 [16] | Finland | To perceive the relationship between perceived environmental barriers to outdoor mobility and loneliness among a community-dwelling older people. | Survey | 848 | Aged 75–90 years | Wald test by applying the delta method | Long distances to services and nearby hills, directly or indirectly, increased loneliness through restricted autonomy in outdoor participation. |

| Siren and Haustein 2016 [22] | Denmark | To observe how retirement affected older adult travel. | Telephone interviews | 864 | Born in 1946 to 1947 | Pearson’s χ2 test, Kruskal–Wallis H-test and variance analysis | Owing to retirement, a clear tendency to reduce car use and mileage were highlighted. |

| Yang et al. 2018 [23] | United States | To examine active travel and public transportation used among older adults, and the built environment characteristics associated with them. | Survey | 180,475 | Aged 45 and above | Linear regression models and logistic regression models | Older adults over the age of 75 made fewer total trips, had lesser variety in travel purposes, and travelled shorter distances. Female elderly with medical conditions, who did not drive and had a lower household income tended to make fewer total trips, reflected a lower diversity of trips and travelled a shorter distance. |

| Shirgaokar et al. 2020 [25] | Canada | To investigate older adults’ unmet travel needs, and the relationship between personal abilities, living situation and socio-demographic factors with the trips not taken. To compare the likelihood of trips not taken following the lack of a ride in urban versus rural areas. | Survey | 1390 | Aged 65 and above | Ordinal logit models | Compared to older adults in urban areas, older adults in rural areas tended not to travel as they lived alone or in low-density housing. |

| Berg 2016 [39] | Sweden | To explore how mobility strategies evolved in the first years of retirement. | Interviews | 27 | Aged 66 to 73 years and retired | Content analysis | During the first year of retirement, significant changes involving illness or a decline in physical and social networks, and changing residence impacted, mobility strategies. |

| Choi and DiNitto 2016 [40] | United States | To investigate alternative modes of transportation used by non-driving older adults and their impact on well-being. | Survey | 12,093 | Aged 65 and above | Stata13/MP’s svy | Non-drivers relied on their informal support system and/or paid assistance to travel. Health deterioration was the most common cause of driving cessation. |

| Corran et al. 2018 [41] | London | To investigate the indicator of immobility in later life. | Travel diary data | 123,562 | Aged 18 and above | Logistic regression model | Retirement and disability were significant contributors to mobility decline. |

| Hjorthol 2013 [42] | Norway | To investigate the distribution of transportation resources among various groups of older people, unmet transportation needs, and their relationship to their well-being. | Survey | 4723 | Aged 67 and above | SPSS | Health, age, and transportation resources (driver’s license and access to a car) significantly impacted the unmet need to visit others, whereas gender and place of living demonstrated no effect. |

| Luiu and Tight 2021 [43] | England | To investigate the factors contributing to travel difficulties among people over the age of 60. | Survey | 4025 | Aged 60 and above | SPSS (descriptive statistics and binomial logistic regressions) | Poor health and well-being, lack of transportation resources, and gender were the main predictors of experiencing travel difficulties later in life. Travel proved more difficult for older people who lived alone or are widowed. |

| Mariotti et al. 2021 [44] | Italy | To explore the motivations of older adults in Milan and Genoa to not take trips and activities, owing to the perceived inadequacy of public transportation. | Survey | 411 | Aged 65 and above | Multivariate logistic regression models | Age, gender, and other control factors were the most significant variables associated with health status, neighbourhood, and LPT satisfaction. Furthermore, perceived LPT service quality and neighbourhood satisfaction influenced the likelihood of abandoning trips and activities: higher satisfaction induced lower likelihood of abandonment. |

| Murray and Musselwhite 2019 [45] | United Kingdom | To investigate the experiences of people who have stopped driving with informal support, following their decision based on individual circumstances. | Semi-structured in-depth interviews | 7 | Aged over 60 years and given up driving within the previous 6 years | Thematic analysis | Physical health issues were the primary reason for quitting driving, which also rendered it impossible to walk or use public transportation. When receiving lifts from family, friends, and neighbours: cars, the element of personal assistance and the accommodation of retired drivers’ physical mobility needs were recognised as important factors. |

| Noh and Joh 2012 [46] | South Korea | To examine elderly travel patterns in Seoul, South Korea. | Survey | 481 | Aged 65 and above | Sequence alignment method | Older age, living alone, a high level of physical disability, a low level of education, long distances from home to the nearest public transportation, having paid work, and the inability to drive discouraged the elderly from travelling. |

| Ryan et al. 2019 [47] | Sweden | To determine which resources and characteristics were associated with fewer opportunities among those aged between 65 and 79 years compared to their peers. | Survey | 1149 | Aged 65–79 | Statistical analyses | Travelling proved complicated due to health issues. Income significantly impacted how people perceived their health. |

| Smith et al. 2016 [48] | Detroit | To investigate the impact of individual and community risk factors on mobility trajectories in a vulnerable community-dwelling elderly population. | Survey data | 1188 | Aged 55 and above | Latent-class growth analysis | Older age, severe mobility impairment, and the fear of falling were risk factors for membership in homebound and infrequent-mobility groups. Being homebound was associated with outdoors barriers. |

| Stjerborg et al. 2015 [49] | Sweden | To identify the daily changing mobility of an elderly couple living in a Swedish suburb. | Semi-structured interviews and time-geographical diaries | 2 | Older couple (married) | Narrative | Older adults were highly dependent on car use. The deterioration of health impacted their mobility ability, and surrounding barriers and authority constraints. |

| Faber and Van-Lierop 2020 [50] | Netherland | To investigate older adults’ mobility needs and desires in the Dutch province of Utrecht, and assess how they envisioned the future use of four different AV scenarios. | Focus group discussion | 24 | Older adults | Content analysis | Elderly perceived barriers to using active modes, such as walking, cycling, and public transportation, due to mobility limitations or fear of an accident. |

| Scott et al. 2023 [51] | Australia | To analyse the frequency of several personal and environmental obstacles. | Telephone survey | 432 | Aged 65 years old or older | - | Physical health was the most frequently reported impediment, followed by sensory issues, financial constraints, and caregiving obligations. |

| Luoma-Halkola and Haikio 2022 [52] | Finland | To explore older individuals’ perspectives of how they manage outdoor mobility and independent living when faced with mobility limitations. | Focus group interview | 28 | Older people | Thematic analysis | The elderly encountered mobility limitations owing to personal health issues and a wide range of contextual factors (inclement weather, lengthy travelling distances, hills, loss of local amenities, construction projects, spousal disease, and institutional aged care and health-care settings). |

| Gong et al. 2022 [53] | China | To identify the barriers to community care access in senior-only urban households. | Phenomenology approach using in-depth interview | 18 | Elderly aged 75 and above | Content analysis | Older persons frequently suffered from multiple chronic conditions that hindered their physical access to care resources. |

| Dickins et al. 2022 [54] | Australia | To determine the barriers to and facilitators of service access for this population. | Semi structured interview | 37 | Elderly women living alone | Thematic analysis | Health was the leading cause of women’s loss of driving privileges, with serious health occurrences precipitating licence revocation. Many participants mentioned that friends and family drove them to engagements; this dependence was usually prefaced by apprehensions and a desire not to disturb them. |

| Kuo et al. 2022 [55] | Taiwan | To analyse the risk factors associated with the longitudinal course of mobility problems and falls. | Data from Taiwan longitudinal study on aging (2003–2015) | 5267 | Middle-aged and older adults | Linear mixed-effects regression models and cumulative logit model analysis | The elderly reported having difficulty standing, walking, kneeling, and jogging. The likelihood of repeated falls, the amount of mobility impairment, cognitive status, living alone, and the number of comorbid conditions rose considerably with age. |

| Nordbakke 2013 [56] | Norway | To examine older women’s daily travel needs, behaviours, and activity participations in an urban setting, and investigate the complex relations between barriers, strategies and alternatives for mobility in old age. | Focus group interviews | 31 | Women aged 67–89 | Thematic | Individual resources, contextual conditions, and strategies were interconnected, thus resulting in the opportunity for mobility. |

| Ozbilen et al. 2022 [57] | Ohio, US | To explore elderly travel patterns with an emphasis on the elements leading to sustainable mobility patterns. | Survey data | 1221 | Aged 60 years or older | Multinomial logistic regression model analysis | In mid-sized, and auto-dependent metropolitan areas, enhancements to the built environment supported sustainable travel among the elderly. |

| Misfud et al. 2019 [58] | Malta | To explore the psychological factors influencing older people’s mobility in Malta. | Survey | 500 | Aged 60 and above | Structural equation modelling | Older people were uncomfortable with public transportation. Their health issues also limited their ability to travel. |

| Mattson 2011 [59] | Dakota | To investigate ageing and mobility problems in rural and small urban areas. | Survey | 1009 | 50–97 years old (AARP member) | Logit model | Public transportation was an option for the elderly who could not or did not intend to drive, but several barriers or problems discouraged their use. |

| Luiu et al. 2018 [60] | Birmingham | To examine the factors influencing elderly travel needs. | Survey | 288 | Aged 60 and above, live in urban area | IBM SPSS Statistics 24 | Car ownership and individuals’ health and wellbeing were the two primary factors influencing travel need fulfilment. |

| Sundling et al. 2016 [61] | Sweden | To determine how negative or positive critical incidents in the public transportation environment affected behaviour, and examine how travel behaviour had changed. | In-depth interview | 30 | Older adult aged 65–91 and experiencing public transport | Qualitative method | Some cases negatively impacted on travel behaviour. Most critical incidents occurred in the physical environment of vehicles and stations/stops, and pricing/ticketing. |

| He et al. 2018 [62] | Hong Kong | To understand the impact of the economy on elderly mobility. | Survey | 47,794 | Aged 18 and above | Descriptive statistics | Some seniors with certain socioeconomic and geographic characteristics encountered potential spatial barriers to fulfil their mobility needs at certain times of the day. |

| Siren et al.2015 [63] | Denmark | To explore the relationship between mobility and well-being by emphasising various types of everyday out-of-home activities. | Semi-structured interviews | 11 | Aged 80–95 (experienced mobility-related limitations) | Qualitative method | With increasing mobility impediments, older adults’ prioritised and selected their activities for only necessary and nearby activities. |

| Ahmad et al. 2019 [64] | Pakistan | To understand elderly individuals’ current mobility characteristics, perceived needs, and limiting factors. | Survey | 450 | Aged 60 years or older | Descriptive and comparative analyses | Vehicle ownership and socio-demographic factors significantly impacted trip-making. Older people were concerned about public transportation and self-driving safety, and the behaviour of transportation crews. |

| Kim et al. 2014 [65] | South Korea | To investigate transportation deficiencies for older adults in Seoul. | Survey | 812 | Aged 65 and lived in Seoul | Ordered logit model | Low-income-earning participants who were 75 or older, with a physical disability, who had given up driving and lived with children in areas with difficult pedestrian conditions, might have limited access to transportation. |

3.3. Socio-Economic Background

3.4. Social Relation Change

3.5. Weather

4. Discussion

4.1. Personal Factors

4.2. Environment Factors

4.3. Recommended Strategies

4.4. Limitation of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DOSM. Malaysia Population Pyramid 2010–2040; Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM): Putrajaya, Malaysia. Available online: https://www.dosm.gov.my (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Gabriel, Z.; Bowling, A. Quality of life from the perspectives of older people. Ageing Soc. 2004, 24, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, S.C.; Porter, M.M.; Menec, V.H. Mobility in older adult: A comprehensive framework. Gerontol. 2010, 50, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L.; Kunkel, S. Aging: The Social Context; Pine Forge Press: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mackett, R. Older people’s travel and relationship to their health and wellbeing. In Transport, Travel and Later Life; Musselwhite, C., Ed.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, G.; Delbosc, A. Exploring public transport usage trends in an ageing population. Transportation 2010, 37, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, P.; Schmöcker, J.D. Active ageing in developing countries?—Trip generation and tour complexity of older people in Metro Manila. J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesel, F.; Rahn, C. Everyday Life in the Suburbs of Berlin: Consequences for the Social Participation of Aged Men and Women. J. Women Aging 2015, 27, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, K.M.N.; Hui, V. An activity-based approach of investigating travel behaviour of older people: Application of a time-space constrained scheduling model (CUSTOM) for older people in the National Capital Region (NCR) of Canada. Transportation 2017, 44, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.L. Critiquing the logic of the domain section of the occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2006, 60, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbakke, S.; Schwanen, T. Transport, unmet activity needs and wellbeing in later life: Exploring the links. Transportation 2015, 42, 1129–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carp, F.M. Transportation in Aging Society: Improving Mobility and Safety for Older People—Special Report 218; National Academic Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, J.; Lucas, K. Workshop 6 Report: Delivering sustainable public transport. Res. Transp. Econ. 2014, 28, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, D. Mobility of Older people and their quality of of life. Transp. Policy 2000, 7, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musselwhite, C.; Haddad, H. Mobility, accessibility and quality of later life. Qual. Ageing Older Adults 2010, 11, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantakokko, M.; Portegijs, E.; Viljanen, A.; Iwarsson, S.; Kauppinen, M.; Rantanen, T. Perceived environmental barriers to outdoor mobility and changes in sense of autonomy in participation outdoors among older people: A prospective two-year cohort study. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasir, R.; Zamani, Z.A.; Khairudin, R.; Sulaiman, W.S.W.; Sani, M.N.M.; Amin, A.S. Hubungan antara kesunyian dan sokongan sosial terhadap kemurungan dalam kalangan wanita hamil tanpa nikah. J. Psikol. Malays. 2016, 30, 152–159. [Google Scholar]

- Zakaria, S.M.; Alavi, K.; Subhi, N. Risiko kesunyian dalam kalangan warga tua di rumah seri kenangan. J. Psychol. Hum. Dev. 2013, 1, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, R.; Momtaz, Y.A.; Hamid, T.A. Social isolation in older malaysians: Prevalence and risk factors. Psychogeriatrics 2013, 13, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, H.; de Bell, S.; Flemming, K.; Sowden, A.; White, P.; Wright, K. Older people’s experiences of everyday travel in the urban environment: A thematic synthesis of qualitative studies in the United Kingdom. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 842–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Tracy, E.L.; Tracy, C.T. A cross-lagged model of depressive symptoms and mobility disability among middle-aged and older Chinese adults with arthritis. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2020, 20, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siren, A.; Haustein, S. How do baby boomers’ mobility patterns change with retirement? Ageing Soc. 2016, 36, 988–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, Y.Q.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Michael, Y.; Zhang, H.M. Active travel, public transportation use, and daily transport among older adults: The association of built environment. J. Transp. Health 2018, 9, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikder, S.; Pinjari, A.R. Immobility levels and mobility preferences of the elderly in the United States: Evidence from 2009 national household travel survey. Transp. Res. Rec. 2012, 2318, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirgaokar, M.; Dobbs, B.; Anderson, L.; Hussey, E. Do rural older adults take fewer trips than their urban counterparts for lack of a ride? J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 87, 102819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, J.A.; Cao, X.; Handy, S.L. Exploring Travel Behavior of Elderly Women in Rural and Small Urban North Dakota: An Ecological Modeling Approach. Transp. Res. Rec. 2008, 2082, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollenkopf, H.; Marcellini, F.; Ruoppila, I. Enhancing Mobility in Later Life: Personal Coping, Environmental Resources and Technical Support; The Out-of-Home Mobility of Older Adults in Urban and Rural Regions of Five European Countries; Ios Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J. The influence of built environment on travel behavior of the elderly in urban China. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 1, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, Q.; Wu, W.; Li, C. Public transport use among the urban and rural elderly in China. J. Transp. Land Use 2018, 11, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamanna, M.; Klinger, C.A.; Liu, A.; Mirza, R.M. The association between public transportation and social isolation in older adults: A scoping review of the literature. Can. J. Aging 2020, 39, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haustein, S.; Siren, A. Older People’s Mobility: Segments, Factors, Trends. Transp. Rev. 2015, 35, 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiu, C.; Tight, M.; Burrow, M. The unmet travel needs of the older population: A review of the literature. Transp. Rev. 2016, 37, 488–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist. Available online: https://prisma-statement.org/documents/PRISMA-ScR-Fillable-Checklist_11Sept2019.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, H.; Yardley, L. Content and thematic analysis. In Research Methods for Clinical and Health Psychology; SAGE: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, A.M. Thematic Analysis; a critical review of its process and evaluation. West East J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 1, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, J. Mobility changes during the first years of retirement. Qual. Ageing Older Adult 2016, 17, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.G.; DiNitto, D.M. Depressive symptoms among older adults who do not drive: Association with mobility resources and perceived transportation barriers. Gerontologist 2016, 36, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corran, P.; Steinbach, R.; Saunders, L.; Green, J. Age, disability and everyday mobility in London: An analysis of the correlates of ‘non-travel’ in travel diary data. J. Transp. Health 2018, 8, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorthol, R. Transport resources, mobility and unmet transport needs in old age. Ageing Soc. 2013, 33, 1190–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiu, C.; Tight, M. Travel difficulties and barriers during later life: Evidence from the national travel survey in England. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 91, 102973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, I.; Burlando, C.; Landi, S. Is local public transport unsuitable for elderly? exploring the cases of two Italian cities. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 40, 100643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Musselwhite, C. Older peoples’ experiences of informal support after giving up driving. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2019, 30, 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.H.; Joh, C.H. Analysis of elderly travel patterns in Seoul metropolitan area, South Korea, through sequence alignment and motif search. Transp. Res. Rec. 2012, 2323, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.; Wretstrand, A.; Schmidt, S.M. Disparities in mobility among older people: Findings from a capability-based travel survey. Transp. Policy 2019, 79, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.R.; Chen, C.; Clarke, P.; Gallagher, N.A. Trajectories of outdoor mobility in vulnerable community-dwelling elderly: The role of individual and environmental factors. J. Aging Health 2016, 28, 796–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stjernborg, V.; Wretstrand, A.; Tesfahuney, M. Everyday life mobilities of older persons—A case study of ageing in a suburban landscape in Sweden. Mobilities 2015, 10, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, K.; Van Lierop, D. How will older adults use automated vehicles? assessing the role of AVs in overcoming perceived mobility barriers. Transp. Res. Part A-Policy Pract. 2020, 133, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.E.; Luszcz, M.A.; Walker, R.; Mazzucchelli, T.; Windsor, T.D. Barriers to activity engagement in older adulthood: Results of a community survey. Australas. J. Ageing 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoma-Halkola, H.; Häikiö, L. Independent living with mobility restrictions: Older people’s perceptions of their out-of-home mobility. Ageing Soc. 2022, 42, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, N.; Meng, Y.; Hu, Q.; Du, Q.; Wu, X.; Zou, W.; Zhu, M.; Chen, J.; Luo, L.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Obstacles to access to community care in urban senior-only households: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickins, M.; Johnstone, G.; Renehan, E.; Lowthian, J.; Ogrin, R. The barriers and enablers to service access for older women living alone in Australia. Ageing Soc. 2022, 42, 849–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F.L.; Yen, C.M.; Chen, H.J.; Liao, Z.Y.; Lee, Y. Trajectories of mobility difficulty and falls in community-dwelling adults aged 50+ in Taiwan from 2003 to 2015. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbakke, S. Capabilities for mobility among urban older women: Barriers, strategies and options. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 26, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbilen, B.; Akar, G.; White, K.; Dabelko-Schoeny, H.; Cao, Q. Analysing the travel behaviour of older adults: What are the determinants of sustainable mobility? Ageing Soc. 2022, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mifsud, D.; Attard, M.; Ison, S. An exploratory study of the psychological determinants of mobility of older people in Malta. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2019, 30, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, J.W. Aging and Mobility in Rural and Small Urban Areas: A Survey of North Dakota. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2011, 30, 700–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luiu, C.; Tight, M.; Burrow, M. An investigation into the factors influencing travel needs during later life. J. Transp. Health 2018, 11, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundling, C.; Nilsson, M.; Hellqvist, S.; Pendrill, L.; Emardson, R.; Berglund, B. Travel behaviour change in old age: The role of critical incidents in public transport. Eur. J. Ageing 2016, 13, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.Y.; Cheung, Y.N.H.Y.; Tao, S. Travel mobility and social participation among older people in a transit metropolis: A socio-spatial-temporal perspective. Transp. Res. Part A-Policy Pract. 2018, 118, 608–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siren, A.; Hjorthol, R.; Levin, L. Different types of out-of-home activities and well-being amongst urban residing old persons with mobility impediments. J. Transp. Health 2015, 2, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Batool, Z.; Starkey, P. Understanding mobility characteristics and needs of older persons in urban Pakistan with respect to use of public transport and self-driving. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 74, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Ulfarsson, G.F.; Sohn, K. Transportation deficiencies for older adults in Seoul, South Korea. Transp. Res. Rec. 2014, 2469, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.J.; Scott-Parker, B.J. Older male and female drivers in car-dependent settings: How much do they use other modes, and do they compensate for reduced driving to maintain mobility? Ageing Soc. 2017, 37, 1249–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollenkopf, H.; Marcellini, F.; Ruappila, I.; Sze´man, Z.; Tacken, M.; Wahl, H.W. Social and behavioural science perspectives on out-of-home mobility in later life: Findings from the European project MOBILATE. Eur. J. Aging 2004, 1, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeom, H.A.; Fleury, J.; Keller, C. Risk Factors for Mobility Limitation in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Social Ecological Perspective. Geriatr. Nurs. 2008, 29, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, K. Dilema Penjagaan Warga Tua; Penerbit UKM: Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge, L.M.; Jette, A.M. The disablement process. Soc. Sci. Med. 1994, 38, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, N.C.; Alavi, K.; Subramaniam, P. Hubungan antara kebimbangan dan kemurungan dengan kualiti hidup warga emas demensia: Keperluan terapi kenangan berkelompok di institusi penjagaan. Univ. Malays. Teren. J. Ndergraduate Res. 2019, 1, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Litwin, H.; Levinson, M. The association of mobility limitation and social networks in relation to late-life activity. Ageing Soc. 2018, 38, 1771–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nation. World Population Aging 2019; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nation: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, T.A.T.; Din, H.M.; Bagat, M.F.; Ibrahim, R. Do Living Arrangements and Social Network Influence the Mental Health Status of Older Adults in Malaysia? Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 624394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binswanger, J.; Carman, K.G. The Role of Decision-Making Processes in the Correlation Between Wealth and Health; Center Discussion Paper Series No. 2011-005; Tilburg University: Tilburg, The Netherlands, 27 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, A.; Hine, J. Rural transport—Valuing the mobility of older people. Res. Transp. Econ. 2012, 34, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, T.; Winters, M.; McKay, H.; Chaudhury, H.; Sims-Gould, J. A grounded visualization approach to explore sociospatial and temporal complexities of older adults’ mobility. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 193, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olawole, M.O.; Aloba, O. Mobility characteristics of the elderly and their associated level of satisfaction with transport services in Osogbo, Southwestern Nigeria. Transp. Policy 2014, 35, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitler, E.; Buys, L. Mobility and out-of-home activities of older people living in suburban environments: ‘because i’m a driver, i don’t have a problem’. Ageing Soc. 2015, 35, 785–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.P. Place Identification and Positive Realities of Aging. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2001, 16, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowles, G.D.; Ravadal, H. Aging, place and meaning in the face of changing circumstances. In Challenges of the Third Age: Meaning & Purpose of Life; Weiss, R.S., Bass, S.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Alavi, K.; Sail, R.M.; Idris, K.; Samah, A.A.; Omar, M. Living arrangement preference and family relationship expectation of elderly parents. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2011, 19, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Alavi, K.; Sutan, R.; Shahar, S.; Manaf, M.R.A.; Jaafar, M.H.; Abdul Maulud, K.N.; Embong, Z.; Keliwon, K.B.; Markom, R. Connecting the Dots between Social Care and Healthcare for the Sustainability Development of Older Adult in Asia: A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novel, L.; Sulaiman, N.S.; Yusoff, N.; Mad Jali, M.F. Naratif sosiologi tingkah laku bunuh diri dalam kalangan warga emas. Akedemika 2020, 90, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide. Active Ageing: A Policy Framework; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Usui, C. Japan’s Population Aging and Silver Industries. In The Silver Market Phenomenon; Kohlbacher, F., Herstatt, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, Y.; Hashimoto, N.; Ando, T.; Sato, T.; Konishi, N.; Takeda, Y.; Akamatsu, M. Associations between motorized transport access, out-of-home activities, and life-space mobility in older adults in Japan. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, M.P.P.; Barros, J.O.; de Almeida, M.H.M.; Mângia, E.F.; Lancman, S. Formal caregivers of older adults: Reflection about their practice. Rev. Saúde Pública 2014, 48, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.R.; Windle, G. Evaluation of an intervention targeting loneliness and isolation for older people in North Wales. Perspect. Public Health 2020, 140, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, O.C.; Blinka, M.D.; Roth, D.L. Non-spouse Companion Accompanying Older Adult to Medical Visit; a qualitative analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 21, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, R.; AntonioPáez, A. Determinants of distance traveled with a focus on the elderly: A multilevel analysis in the Hamilton CMA, Canada. J. Transp. Geogr. 2009, 17, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes | Health | Build Environment | Socio-Economic Background | Social-Relation Changes | Weather |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-themes | Mobility impairment, illness, fear of falling | House location, hills, facilities, structure, public transport issues, urbanization | Education, income, license and car ownership | Living alone, losing spouse, losing family or close friends, moving to other location, retirement | Heavy rain/snow |

| Number of included studies | 19 | 16 | 14 | 11 | 2 |

| References | [11,25,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55] | [11,16,42,43,44,46,50,51,52,56,57,58,59,60,61,62] | [11,22,23,39,41,42,43,46,47,56,60,62,63,64] | [11,25,39,43,46,49,51,53,54,55,65] | [16,52] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Che Had, N.H.; Alavi, K.; Md Akhir, N.; Muhammad Nur, I.R.; Shuhaimi, M.S.Z.; Foong, H.F. A Scoping Review of the Factor Associated with Older Adults’ Mobility Barriers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054243

Che Had NH, Alavi K, Md Akhir N, Muhammad Nur IR, Shuhaimi MSZ, Foong HF. A Scoping Review of the Factor Associated with Older Adults’ Mobility Barriers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054243

Chicago/Turabian StyleChe Had, Nur Hasna, Khadijah Alavi, Noremy Md Akhir, Irina Riyanti Muhammad Nur, Muhammad Shakir Zufayri Shuhaimi, and Hui Foh Foong. 2023. "A Scoping Review of the Factor Associated with Older Adults’ Mobility Barriers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054243

APA StyleChe Had, N. H., Alavi, K., Md Akhir, N., Muhammad Nur, I. R., Shuhaimi, M. S. Z., & Foong, H. F. (2023). A Scoping Review of the Factor Associated with Older Adults’ Mobility Barriers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054243