Effects of Online Video Sport Spectatorship on the Subjective Well-Being of College Students: The Moderating Effect of Sport Involvement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Hypothesis Development

2.1. SWB

2.2. Sports and SWB

2.3. Sport Involvement as a Moderator

3. Participants and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Sample Size Calculation

3.3. Experimental Procedure and Implementation

3.4. Study Protocol

3.5. Measurements

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Results

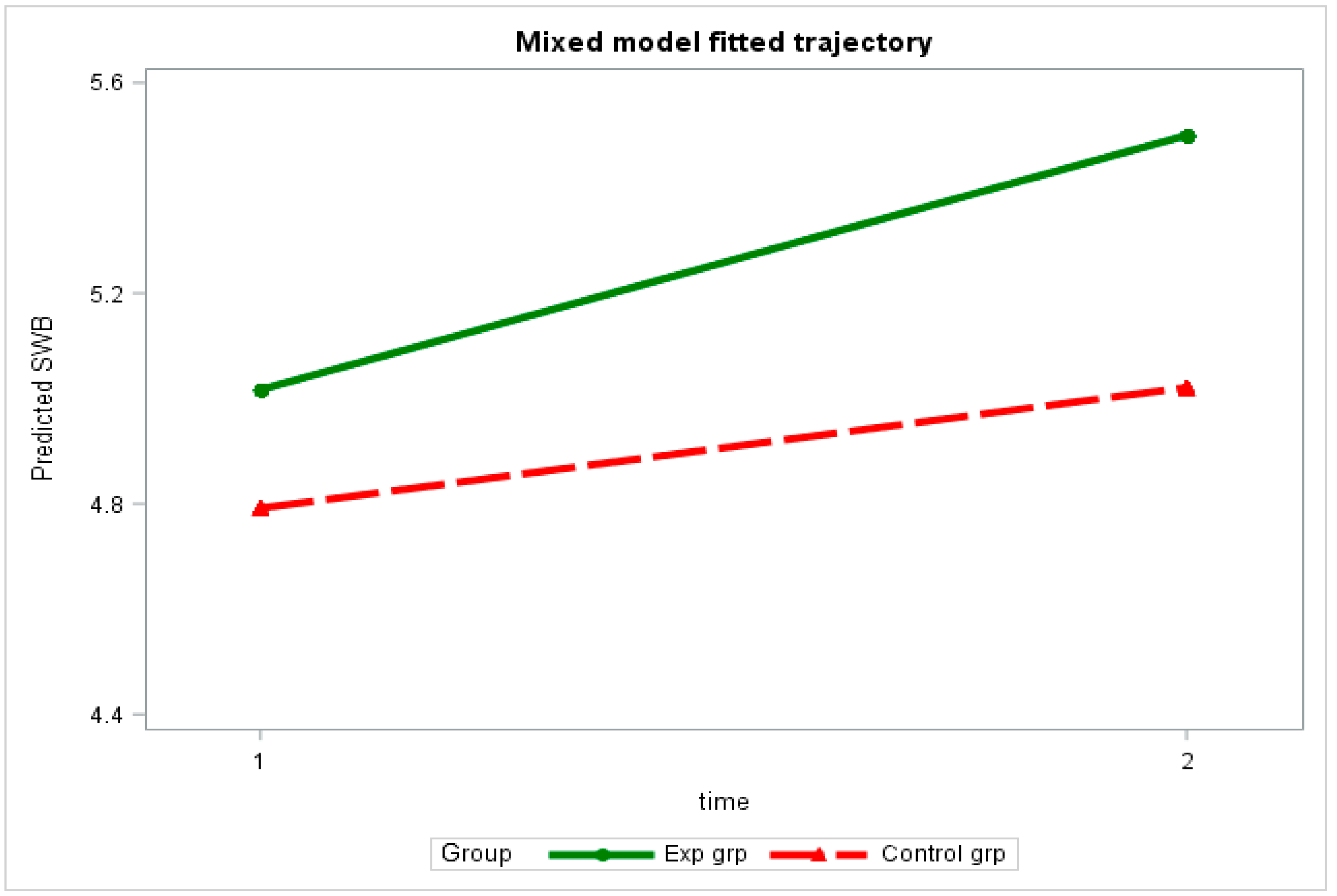

4.1. Results of H1 Testing

4.2. Results of H2 Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. OVSS and SWB

5.3. Moderating Effect of Sport Involvement

5.4. Practical Implications

5.5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D’Agostino, A.; Grilli, G.; Regoli, A. The determinants of subjective well-being of young adults in Europe. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 14, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seehuus, M.; Moeller, R.W.; Peisch, V. Gender effects on mental health symptoms and treatment in college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 69, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Barrington-Leigh, C.P. Measuring and understanding subjective well-being. Can. J. Econ. Revue Can. Conomique 2010, 43, 729–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silva, A.; Monteiro, D.; Sobreiro, P. Effects of sports participation and the perceived value of elite sport on subjective well-being. Sport Soc. 2019, 23, 1202–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, L. Sport and dance interventions for healthy young people (15–24 years) to promote subjective well-being: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jetzke, M.; Mutz, M. Sport for pleasure, fitness, medals or slenderness? Differential effects of sports activities on well-being. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2020, 15, 1519–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.R.; Luo, J. The relationship among college students’ physical exercise, self-efficacy, emotional intelligence, and subjective well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, P.; Schulte, J.; Raube, S.; Disouky, H.; Kandler, C. The role of leisure interest and engagement for subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 1135–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Wann, D.L.; Lock, D.; Sato, M.; Moore, C.; Funk, D.C. Enhancing older adults’ sense of belonging and subjective well-being through sport game attendance, team identification, and emotional support. J. Aging Health 2020, 32, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jang, W.; Lee, J.S.; Wann, D.L.L. Delay effect of sport media consumption on sport consumers’ subjective well-being: Moderating role of team identification. Sport Mark. Q. 2021, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lera-Lopez, F.; Ollo-Lopez, A.; Sanchez-Santos, J.M. Is passive sport positively associated with happiness? Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2021, 13, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.; Kim, Y. College students’ social media use and communication network heterogeneity: Implications for social capital and subjective well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; James, J.D. Sport and happiness: Understanding the relations among sport consumption activities, long- and short-term subjective well-being, and psychological need fulfillment. J. Sport Manag. 2019, 33, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, D.H. Improving well-being through hedonic, eudaimonic, and social needs fulfillment in sport media consumption. Sport Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal, R. Measuring the multidimensional nature of sporting event performance consumption. J. Leis. Res. 2006, 38, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Advances and open questions in the science of subjective well-being. Collabra Psychol. 2018, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, C.; Kaplanidou, K. The effect of sport involvement on support for mega sport events: Why does it matter? Sustainability 2019, 11, 5687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jang, W.; Kim, Y.J.; Chang, K.; Kim, T. The effects of high-tech cameras on sports consumers’ viewing experiences: The moderating role of sports involvement. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2022, 23, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutz, M.; Gerke, M. Major sporting events and national identification: The moderating effect of emotional involvement and the role of the media. Commun. Sport. 2018, 6, 605–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poiesz, T.B.; Bont, C. Do we need involvement to understand consumer behavior? Adv. Consum. Res. 1995, 22, 448–452. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Sujective Well-Being: The Science of Happiness and Life Satisfaction. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Brickman, P.; Campbell, D.T. Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In Adaptation-Level Theory; Appley, M.H., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971; pp. 287–305. [Google Scholar]

- Passmore, H.A.; Howell, A.J.; Holder, M.D. Positioning implicit theories of well-being within a positivity framework. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 19, 2445–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Lyubomirsky, S. How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. J. Posit. Psychol. 2006, 1, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkach, C.; Lyubomirsky, S. How do people pursue happiness?: Personality, happiness-increasing strategies, and well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2006, 7, 183–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J.; Tang, B.; Goh, B. Exploring the influence of audiences’ subjective well-being in sport event: The moderating role of leisure engagement. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2020, 16, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, C.W.; Kuykendall, L.; Tay, L. Get active? A meta-analysis of leisure-time physical activity and subjective well-being. J Posit. Psychol. 2018, 13, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyle, M. The Psychology of Happiness; Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gantz, W.; Wang, Z.; Paul, B.; Potter, R.F. Sports versus all comers: Comparing TV sports fans with fans of other programming genres. J. Broadcast. Electron. 2006, 50, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trail, G.T.; James, J.D. Sport Consumer Behavior, 2nd ed.; Sport Consumer Research Consultants LLC.: Seattle, WA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the involvement construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, S.R.; Chalip, L. Effects of commercialism and nationalism on enjoyment of an event telecast: Lessons from the Atlanta Olympics. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2002, 2, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.H.; Tang, Y.Y. Job stress and well-being of female employees in hospitality: The role of regulatory leisure coping styles. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1038–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.Z. Relationship between leisure activities and stress, depression, well-being of undergraduates. Chin. Gen. Pract. 2015, 18, 2341–2345. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.Y.; Lin, Y.H. Persuasion effect of corporate social responsibility initiatives in professional sport franchise: Moderating effect analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieger, S.; Götz, F.M.; Gehrig, F. Soccer results affect subjective well-being, but only briefly: A smartphone study during the 2014 FIFA World Cup. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Anokye, N.; Mansfield, L.; Kay, T.; Sanghera, S.; Lewin, A.; Fox-Rushby, J. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a complex community sport intervention to increase physical activity: An interrupted time series design. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e024132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkvord, F.; Anschütz, D.; Geurts, M. Watching TV cooking programs: Effects on actual food intake among children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flurry, L.A.; Swimberghe, K.; Allen, J. Exposing the moderating impact of parent-child value congruence on the relationship between adolescents’ materialism and subjective well-being. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.; Absher, J.; Norman, W.; Hammitt, W.; Jodice, L. A modified involvement scale. Leis. Stud. 2007, 26, 399–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craske, M.G.; Niles, A.N.; Burklund, L.J.; Wolitzky-Taylor, K.B.; Vilardaga, J.C.P.; Arch, J.J.; Lieberman, M.D. Randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy for social phobia: Outcomes and moderators. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mesri, B.; Niles, A.N.; Pittig, A.; LeBeau, R.T.; Haik, E.; Craske, M. Public speaking avoidance as a treatment moderator for social anxiety disorder. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2017, 55, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, D.; Kluger, A.N. Task type as a moderator of positive/negative feedback effects on motivation and performance: A regulatory focus perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 1084–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experiment Group | Control Group | Total | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 30) | (n = 24) | (n = 54) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 17 (56.7%) | 14 (58.3%) | 31 (57.4%) | 0.9020 |

| Female | 13 (43.3%) | 10 (41.7%) | 23 (42.6%) | |

| IN, Mean (SD) | 4.8 (1.37) | 4.1 (1.64) | 4.5 (1.52) | 0.11121 |

| SWB at T1, Mean (SD) | 5.0 (1.13) | 4.8 (1.34) | 4.9 (1.22) | 0.50581 |

| SWB at T2, Mean (SD) | 5.5 (0.97) | 5.0 (1.38) | 5.3 (1.18) | 0.14101 |

| Items | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Subjective well-being (pretest) | ||

| 1. I am happy with my life. | 4.96 | 1.23 |

| 2. In most ways, my life is close to perfect. | 4.87 | 1.30 |

| Satisfaction well-being (posttest) | ||

| 1. I am happy with my life. | 5.24 | 1.21 |

| 2. In most ways, my life is close to perfect. | 5.33 | 1.23 |

| Sport involvement | ||

| Attraction | ||

| 1. Sport is one of the most enjoyable things I do. | 4.69 | 1.74 |

| 2. Sport is very important to me. | 4.31 | 1.83 |

| 3. Sport is one of the most satisfying things I do. | 4.39 | 1.71 |

| Centrality | ||

| 4. A considerable portion of my life revolves around sports. | 4.48 | 1.82 |

| 5. Sports play a central role in my life. | 4.24 | 1.81 |

| 6. Changing my preference from sports to any other recreational activity would require substantial rethinking. | 4.07 | 1.76 |

| Social bonding | ||

| 7. I enjoy discussing sports with my friends. | 4.57 | 1.87 |

| 8. Most of my friends are in some way connected with sports. | 4.85 | 1.72 |

| 9. Participating in sports provides me with an opportunity to spend time with friends. | 4.48 | 1.87 |

| Identity affirmation | ||

| 10. When I participate in sports, I can be myself. | 4.59 | 1.79 |

| 11. I resonate with people and media associated with sports. | 4.83 | 1.60 |

| 12. When playing sports, I do not have to be concerned about my appearance. | 4.89 | 1.57 |

| Identity expression | ||

| 13. You can tell a lot about people by seeing them play sports. | 4.74 | 1.68 |

| 14. Sport participation says a lot about who I am. | 3.81 | 1.57 |

| 15. When I participate in sports, others see me the way I want them to see me. | 3.91 | 1.56 |

| Effect | Beta | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 0.731 | 0.213 | 3.430 | 0.001 * |

| OVSS | 0.555 | 0.434 | 1.280 | 0.207 |

| Involvement | 1.387 | 0.415 | 3.340 | 0.002 * |

| Time × OVSS | −0.731 | 0.296 | −2.470 | 0.017 * |

| OVSS × involvement | −1.373 | 0.624 | −2.200 | 0.033 * |

| Time × involvement | −0.437 | 0.283 | −1.540 | 0.130 |

| Time × OVSS × involvement | 0.987 | 0.426 | 2.320 | 0.024 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, Y.-H.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-K.; Lee, C.-Y.; Cheng, C.-Y. Effects of Online Video Sport Spectatorship on the Subjective Well-Being of College Students: The Moderating Effect of Sport Involvement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054381

Lin Y-H, Chen C-Y, Lin Y-K, Lee C-Y, Cheng C-Y. Effects of Online Video Sport Spectatorship on the Subjective Well-Being of College Students: The Moderating Effect of Sport Involvement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054381

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Yi-Hsiu, Chen-Yueh Chen, Yen-Kuang Lin, Chen-Yin Lee, and Chia-Yi Cheng. 2023. "Effects of Online Video Sport Spectatorship on the Subjective Well-Being of College Students: The Moderating Effect of Sport Involvement" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054381