Stepping into the Void: Lessons Learned from Civil Society Organizations during COVID-19 in Rio de Janeiro

Abstract

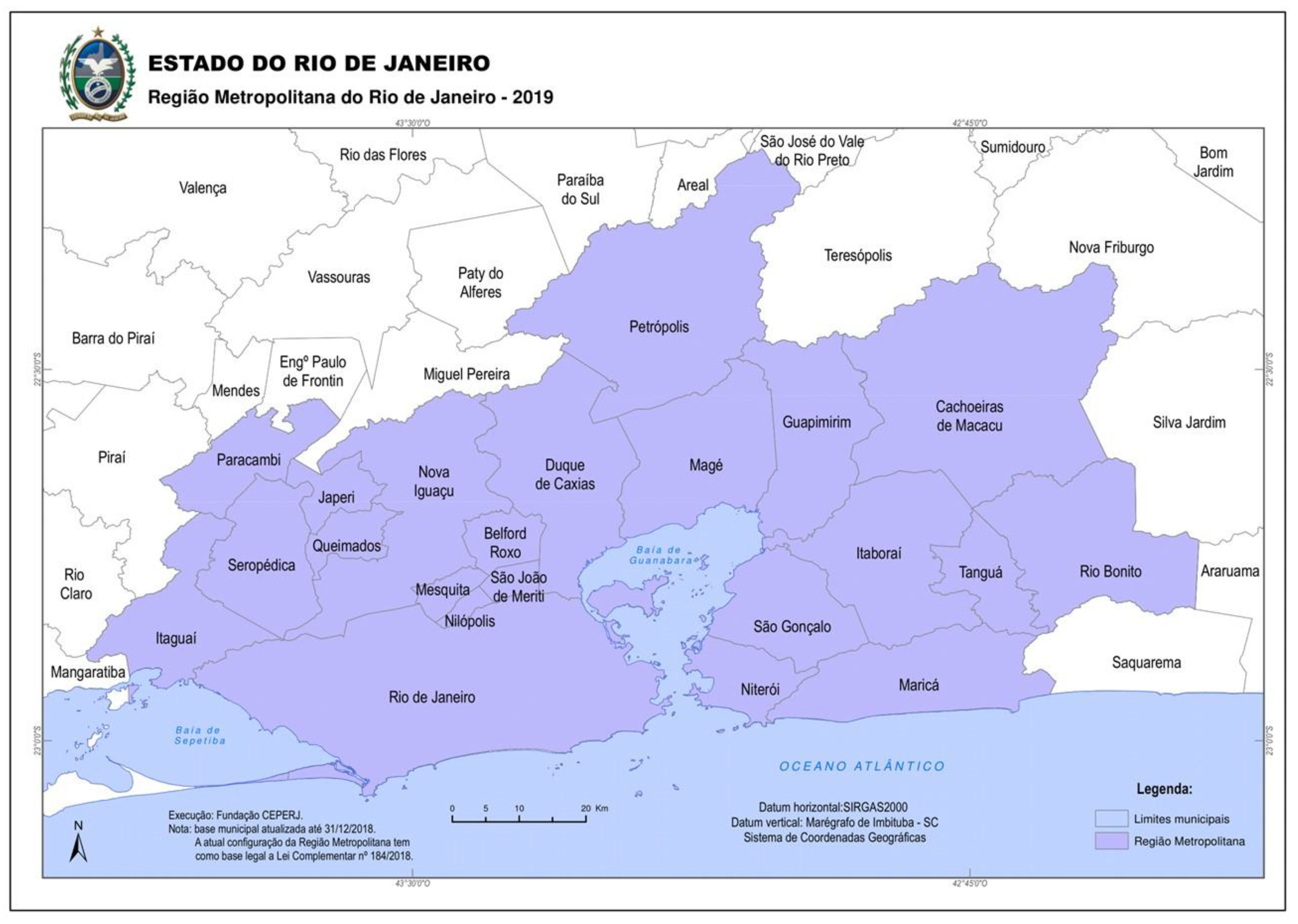

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on WASH-Deprived Populations

I have been hearing stories of the homeless population being more contaminated. This was when everybody started going to the beach, going out, gathering at parties.(KI1, serving the homeless in the Capital)

| Sub-Theme | Participants Mentioning (n = 15) | % | Number of Mentions | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High rate of infections observed | 5 | 33% | 7 | 30% |

| Low rate of infections observed | 4 | 27% | 6 | 26% |

| Unknown rate of infections | 3 | 20% | 3 | 13% |

| TOTAL | 23 | 100% |

There is no data because the issue of sub-notification is grave. But we see through social media, there is not a day that you go online and there isn’t someone grieving. I think this is a great indicator.(KI11, serving those of low income in the Periphery)

It was harder for women because some worked doing hair, nails, a lot of interpersonal contact. In the beginning, people didn’t want close contact .(KI15, serving those of low income and the homeless in the Periphery)

Hunger arrived before the virus in slums because the population that lived without formal employment earned at lunchtime what they would buy for dinner, and they lost their income.(KI3, serving the slums and those of low income in the Capital and Periphery)

In the beginning, they were scared because we came with gloves, masks, face shields, etc. This caused a lot of surprises and distancing.(KI1, serving the homeless in the Capital)

I heard many stories of people who left the streets and were able to pay the rent of a small room with the emergency aid. After its suspension, they could no longer pay rent.(KI1, serving the homeless in the Capital)

I observed a very large increase in women on the streets. Some live in nearby communities and end up commuting to get food for their families. And women with kids and without partners, which is a new profile.(KI10, serving the homeless in the Capital)

Everybody observed an increase in service. We had around 800 weekly actions. Suddenly it jumped to 1200. The street population remained the same, but we had an increase in informal workers.(KI10, serving the homeless in the Capital)

There were violent actions in Rio de Janeiro where homeless people were fined for not wearing masks. Keep in mind that the mayor decided to buy paper masks that looked like birthday hats for the vulnerable population.(KI1, serving the homeless in the Capital)

Organizations that welcome LGBTQIA+ when they are kicked out of their houses had to be closed during lockdowns. So, LGBTQIA+ people who were already vulnerable because they had to live with violent parents, were now having to social isolate with them.(KI12, serving the homeless and those of low income in the Capital)

3.2. CSO Initiatives during the COVID-19 Pandemic

We adapted. We couldn’t be face to face with the people we were dealing with. Before, I would go to CEDAE [state water company], to the state assembly, watch the deliberations and confront the decision-makers.(KI2, serving the slums in the Capital)

| Sub-Theme | Participants Mentioning (n = 15) | % | Number of Mentions | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suspended in-person activities | 8 | 53% | 17 | 20% |

| Reduced or adapted in-person activities | 7 | 47% | 12 | 14% |

| Increased scope or area of focus | 8 | 53% | 11 | 13% |

| Changed focus to relief aid | 8 | 53% | 10 | 12% |

| Reduced connection with assisted population | 5 | 33% | 9 | 11% |

| TOTAL | 83 | 100% |

We thought long and hard about how are we going to propose therapy from home since it’s usually the space where people are abused. Are people going to feel free to speak inside the house?.(KI2 serving the slums in the Capital)

We were frustrated for not being able to perform our regular activities. Our organization’s mandate was never to provide emergency relief, to donate meals, etc.(KI10, serving the homeless in the Capital)

| Sub-Theme | Participants Mentioning (n = 15) | % | Number of Mentions | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal education | 10 | 67% | 15 | 18% |

| Art and culture | 6 | 40% | 12 | 14% |

| Health support | 7 | 47% | 12 | 14% |

| Income generation | 7 | 47% | 9 | 11% |

| Political incidence | 4 | 27% | 9 | 11% |

| Food donation | 3 | 20% | 7 | 8% |

| WASH | 5 | 33% | 7 | 8% |

| Community development | 5 | 33% | 7 | 8% |

| Sheltering or housing | 3 | 20% | 4 | 5% |

| Research | 1 | 7% | 1 | 1% |

| Facilitating access to assistance programs | 1 | 7% | 1 | 1% |

| TOTAL | 84 | 100% |

| Sub-Theme | Participants Mentioning (n = 15) | % | Number of Mentions | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food donation | 13 | 87% | 33 | 11% |

| Partnering with local/regional CSOs | 12 | 80% | 28 | 10% |

| Donation of hygiene kits | 13 | 87% | 27 | 9% |

| Water donation | 9 | 60% | 22 | 8% |

| Raising awareness about COVID-19 | 9 | 60% | 19 | 7% |

| Donation of PPE | 11 | 73% | 16 | 5% |

| Fundraising for relief aid | 8 | 53% | 15 | 5% |

| Raising awareness about hygiene practices/public health measures | 5 | 33% | 10 | 3% |

| Partnering with communities/individuals | 8 | 53% | 10 | 3% |

| Partnering with private organizations | 6 | 40% | 9 | 3% |

| Formal education | 5 | 33% | 9 | 3% |

| TOTAL | 292 | 100% |

Many groups made banners in the favelas stressing the importance of handwashing and prevention.(KI2, serving the slums in the Capital)

We had partnerships with different organizations to provide showers or services of documentation. When the opportunity shows up, we provide the service.(KI10, serving the homeless in the Capital)

I only work in partnership. I don’t see another way without partnerships. When someone leaves the streets definitively, other projects acted there so that they could be successful.(KI5, serving the homeless in the Capital)

We always had to supply the community with water. We started installing some very large water tanks with lids. And each family takes what they need. The water truck comes, fills it up, the water stays in a covered container, tidy, and clean.(KI6, serving the slums in the Periphery)

| Sub-Theme | Participants Mentioning (n = 15) | % | Number of Mentions | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No direct supply | 12 | 80% | 22 | 61% |

| Intermittent supply | 4 | 27% | 12 | 33% |

| Regular supply | 2 | 13% | 2 | 6% |

| TOTAL | 36 | 100% |

There’s nothing else left to affect the street population. If the water is good, they don’t have water. If the water is bad, they don’t have water. Those who donate bring good water.(KI9, serving the homeless in the Capital)

| Sub-Theme | Participants Mentioning (n = 15) | % | Number of Mentions | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remained unsafe | 5 | 33% | 5 | 63% |

| Worsened | 2 | 13% | 3 | 38% |

| TOTAL | 8 | 100% |

We don’t have public washrooms or sinks in the city. They end up bathing in the sea, in waterfalls or paying to shower somewhere else. Often, they must choose between the food or the shower.(KI10, serving the homeless in the Capital)

| Sub-Theme | Participants Mentioning (n = 15) | % | Number of Mentions | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No washrooms | 10 | 67% | 20 | 44% |

| No sewage treatment | 5 | 33% | 8 | 18% |

| Hygiene facility provided by others | 3 | 20% | 6 | 13% |

| Improvised washrooms | 2 | 13% | 3 | 7% |

| Shared washrooms | 2 | 13% | 3 | 7% |

| Paid hygiene facilities | 2 | 13% | 3 | 7% |

| Inadequate sewage treatment | 2 | 13% | 2 | 4% |

| TOTAL | 45 | 100% |

3.3. Perceived Level of Success of Interventions

It consisted of sinks made of plywood and plastic, with a tap and all, where the homeless population would wash their hands. It was brilliant.(KI13, serving the homeless in the Capital)

In deserted places, the sinks were destroyed. Otherwise, the reception was good. They truly embraced it.(KI5, serving the homeless in the Capital and Periphery)

In many campaigns, we knew how to capture this feeling, this driving force to help and we redirected it to donations.(KI2, serving the slums in the Capital)

They don’t wear masks. There is no form of isolation. In Jardim Gramacho, you go to a drug store and not even the receptionists wear masks.(KI6, serving the slums in the Periphery)

At the beginning of the pandemic, the president spread that it was just a flu, that we would only lose 800 people. That heavily affected the way people saw the pandemic.(KI15, serving the homeless and those of low income in the Periphery)

The government took a long time to reach these people, so the NGOs and collective groups provided aid to them.(KI11, serving those of low income in the Periphery)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO; UNICEF. Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2000–2017: Special Focus on Inequalities. 2017. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/progress-on-drinking-water-sanitation-and-hygiene-2019 (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Johns Hopkins University. COVID-19 Map. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. 22 January 2020. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- SNIS. Sistema Nacional de Informações Sobre Saneamento: 25° Diagnóstico dos Serviços de Água e Esgotos. 2019. Available online: http://www.snis.gov.br/diagnostico-anual-agua-e-esgotos/diagnostico-dos-servicos-de-agua-e-esgotos-2019 (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Bisung, E.; Elliott, S.J. Psychosocial impacts of the lack of access to water and sanitation in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. J. Water Health 2017, 15, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, M.C.; Stocks, M.E.; Cumming, O.; Jeandron, A.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Wolf, J.; Prüss-Ustün, A.; Bonjour, S.; Hunter, P.R.; Fewtrell, L.; et al. Systematic review: Hygiene and health: Systematic review of handwashing practices worldwide and update of health effects. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2014, 19, 906–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. Safe Water, Better Health. World Health Organization. 2019. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329905/9789241516891-eng.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Hillier, M.D. Using effective hand hygiene practice to prevent and control infection. Nurs. Stand. 2020, 35, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senado Federal. PEC 6/2021 (Fase 1—CD). 2021. Available online: https://www.camara.leg.br/propostas-legislativas/2277279 (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Aith, F.M.A.; Rothbarth, R.O. Estatuto jurídico das águas no Brasil. Estud. Av. 2015, 29, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UN-Water. Summary Progress Update 2021: SDG 6—Water and Sanitation for All. UN-Water Integrated Monitoring Initiative. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwater.org/new-data-on-global-progress-towards-ensuring-water-and-sanitation-for-all-by-2030/ (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Sistema Nacional de Informações sobre Saneamento. Diagnóstico Temático Serviços de Água e Esgoto Visão Geral; Sistema Nacional de Informações sobre Saneamento: Brasília, Brazil, 2022.

- De Paula, H.C.; Daher, D.V.; Koopmans, F.F.; Faria, M.G.A.; Lemos, P.F.S.; Moniz, M.A. No Place to Shelter: Ethnography of the Homeless Population in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73, e20200489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- G1 Rio. Como Doar Para O Combate Ao Coronavírus no RJ. G1, 27 March 2020. Available online: https://g1.globo.com/rj/rio-de-janeiro/noticia/2020/03/27/moradores-criam-rede-de-solidariedade-para-recolher-e-distribuir-alimentos-no-rio.ghtml (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Cabopianco, M. Coronavírus: Conheça Projetos Sociais que Fazem Doações a Quem Precisa. Veja Rio, 2 April 2020. Available online: https://vejario.abril.com.br/coronavirus/doacoes-campanhas-ajuda-covid-pandemia/ (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Elliott, S.J. Global health for all by 2030. Can. J. Public Health 2022, 113, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, M.; Masombuka, L.N. Failed Intentions? Meeting the Water Needs of People Living with HIV in South Africa. Water SA 2020, 46, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, A.C.; Willms, D.; Schuster-Wallace, C.; Watt, S. From Rhetoric to Reality: An NGO’s Challenge for Reaching the Furthest behind. Dev. Pract. 2017, 27, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, C.; Elliott, S.J.; Matthews, R.; Elliott, B. The Political Ecology of Health: Perceptions of Environment, Economy, Health and Well-being among ‘Namgis First Nation. Health Place 2005, 11, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B. Political ecologies of health. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 34, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Governo do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. “Lei Complementar 184/18”. Jusbrasil. 2018. Available online: https://gov-rj.jusbrasil.com.br/legislacao/661847132/lei-complementar-184-18-rio-de-janeiro-rj (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- IBGE. Tabelas Complementares—Estimativas da População 2021. Available online: https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-detalhe-de-midia.html?view=mediaibge&catid=2103&id=4956 (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Da Silva, L.H.P. De Recôncavo da Guanabara à Baixada Fluminense: Leitura de um Território pela História. Recôncavo Rev. História UNIABEU 2013, 3, 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fortes, A.; de Oliveira, L.D.; de Sousa, G.M. A COVID-19 na Baixada Fluminense: Colapso e apreensão a partir da periferia metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro. Espaço E Econ. 2020, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Casa Fluminense. Mapa Da Desigualdade: Região Metropolitana Do Rio de Janeiro. Available online: https://casafluminense.org.br/mapa-da-desigualdade/ (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- UFRJ. Nota Técnica da UFRJ Sobre os Problemas da Qualidade da Água que a População do Rio de Janeiro Está Vivenciando. 2020. Available online: https://ufrj.br/sites/default/files/img-noticia/2020/01/nota_tecnica_-_caso_cedae.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample Sizes for Saturation in Qualitative Research: A Systematic Review of Empirical Tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Presidência da República. Lei nº 13.982, de 2 de Abril de 2020. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2019-2022/2020/lei/l13982.htm (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Cardoso, B.B. The Implementation of Emergency Aid as an Exceptional Measure of Social Protection. Rev. Adm. Pública 2020, 54, 1052–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Cidadania. Auxílio Emergencial 2021. Governo Brasileiro. Available online: https://www.gov.br/cidadania/pt-br/servicos/auxilio-emergencial (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Santos, D.D.S.; Bittencourt, E.A.; Malinverni, A.C.D.M.; Kisberi, J.B.; Vilaça, S.d.F.; Iwamura, E.S.M. Domestic Violence against Women during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Forensic Sci. Int. Rep. 2022, 5, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haworth, B.T.; Cassal, L.C.B.; Muniz, T.D.P. ‘No-one Knows How to Care for LGBT Community like LGBT Do’: LGBTQIA+ Experiences of COVID-19 in the UK and Brazil. Disasters 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, F.; Orsini, M. Governing COVID-19 without government in Brazil: Ignorance, neoliberal authoritarianism, and the collapse of public health leadership. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 1257–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Fonseca, E.M.; Nattrass, N.; Lazaro, L.L.B.; Bastos, F.I. Political discourse, denialism and leadership failure in Brazil’s response to COVID-19. Glob. Public Health 2021, 16, 1251–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, F.; Béhague, D. Contested leadership and the governance of COVID-19 in Brazil: The role of local government and community activism. Glob. Public Health 2022, 17, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, F.M.; McCall, S.J.; Ayoub, H.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Mumtaz, G.R. Vulnerability of Syrian refugees in Lebanon to COVID-19: Quantitative insights. Confl. Health 2021, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, C.D.F.; Machado, M.F.; Do Carmo, R.F. Human development, social vulnerability and COVID-19 in Brazil: A study of the social determinants of health. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, R.; Kajal, F.; Jahan, N.; Mushi, V. Now or Never: Will COVID-19 Bring about Water and Sanitation Reform in Dharavi, Mumbai? Local Environ. 2021, 26, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A. Preventing COVID-19 Amid Public Health and Urban Planning Failures in Slums of Indian Cities. World Med. Health Policy 2020, 12, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasdani, K.P.; Prasad, A. The Impossibility of Social Distancing among the Urban Poor: The Case of an Indian Slum in the Times of COVID-19. Local Environ. 2020, 25, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.K. Making COVID-19 Prevention Etiquette of Social Distancing a Reality for the Homeless and Slum Dwellers in Ghana: Lessons for Consideration. Local Environ. 2020, 25, 536–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Pesquisa Nacional Por Amostra de Domicílios: PNAD COVID19. 2020. Available online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv101763.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- FGV; TETO. COVID-19: Dificuldades e Superações Nas Favelas. 2021. Available online: https://conteudo.teto.org.br/fgv-e-teto (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Brauer, M.; Zhao, J.T.; Bennitt, F.B.; Stanaway, J.D. Global access to Handwashing: Implications for COVID-19 control in low-income countries. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020, 128, 057005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shermin, N.; Rahaman, S.N. Assessment of sanitation service gap in urban slums for tackling COVID-19. J. Urban Manag. 2021, 10, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.M.; Das, S.; Hanifi, S.M.A.; Shafique, S.; Rasheed, S.; Reidpath, D.D. A place-based analysis of COVID-19 risk factors in Bangladesh urban slums: A secondary analysis of World Bank microdata. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Betancur, J.C.; Martínez-Herrera, E.; Pericàs, J.M.; Benach, J. Coronavirus disease 2019 and slums in the Global South: Lessons from Medellín (Colombia). Glob. Health Promot. 2021, 28, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, M.; Nyamandi, V.; Siachema, C.; Shirihuru, N.; Dhoba, L.; Baggen, A.; Kanyowa, T.; Mwenda, J.; Dodzo, L.; Manangazira, P.; et al. Using the Water and Sanitation for Health Facility Improvement Tool (WASH FIT) in Zimbabwe: A Cross-Sectional Study of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Services in 50 COVID-19 Isolation Facilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A. ‘A little flu’: Brazil’s Bolsonaro Playing down Coronavirus Crisis. Euronews, 6 April 2020. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/2020/04/06/a-little-flu-brazil-s-bolsonaro-playing-down-coronavirus-crisis (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Cardwell, F.S.; Elliott, S.J.; Chin, R.; Pierre, Y.S.; Choi, M.Y.; Urowitz, M.B.; Ruiz-Irastorza, G.; Bernatsky, S.; Wallace, D.J.; Petri, M.A.; et al. Health Information Use by Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) Pre and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Lupus Sci. Med. 2022, 9, e000755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGraw, M.; Stein, S. It’s Been Exactly One Year Since Trump Suggested Injecting Bleach. We’ve Never Been the Same. Politico, 23 April 2021. Available online: https://www.politico.com/news/2021/04/23/trump-bleach-one-year-484399 (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Zvobgo, L.; Do, P. COVID-19 and the call for ‘Safe Hands’: Challenges facing the under-resourced municipalities that lack potable water access—A case study of Chitungwiza municipality, Zimbabwe. Water Res. X 2020, 9, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, N.R.A. The power that comes from within: Female leaders of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas in times of pandemic. Glob. Health Promot. 2021, 28, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, R.; Redding, D.W.; Chin, K.Q.; Donnelly, C.A.; Blackburn, T.M.; Newbold, T.; Jones, K.E. Zoonotic host diversity increases in human-dominated ecosystems. Nature 2020, 584, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.F.; Goldberg, M.; Rosenthal, S.; Carlson, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, C.; Ramachandran, S. Global rise in human infectious disease outbreaks. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Sub-Theme | Participants Mentioning (n = 15) | % | Number of Mentions | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income loss | 9 | 60% | 15 | 29% |

| More people seeking assistance | 8 | 53% | 9 | 18% |

| Generalized fear or confusion | 7 | 47% | 7 | 30% |

| Diversified profile of assistance seekers | 4 | 27% | 7 | 14% |

| Increased policing | 3 | 20% | 6 | 12% |

| Increased domestic violence | 5 | 33% | 6 | 12% |

| TOTAL | 51 | 100% |

| Sub-Theme | Participants Mentioning (n = 15) | % | Number of Mentions | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unsafe piped water | 6 | 40% | 7 | 47% |

| Unsafe water from alternative sources | 6 | 40% | 7 | 47% |

| Safe water from alternative sources | 1 | 7% | 1 | 7% |

| TOTAL | 15 | 100% |

| Sub-Theme | Participants Mentioning (n = 15) | % | Number of Mentions | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Successful initiatives | ||||

| Installation of mobile sinks | 4 | 27% | 9 | 41% |

| Fundraising | 3 | 20% | 5 | 23% |

| General public engagement | 3 | 20% | 3 | 14% |

| Adoption of hygiene practices | 2 | 13% | 3 | 14% |

| Public health compliance | 1 | 7% | 1 | 5% |

| TOTAL | 22 | 100% | ||

| Unsuccessful initiatives | ||||

| Public health compliance (other than masks) | 5 | 33% | 6 | 25% |

| Adoption of masks | 4 | 27% | 6 | 25% |

| Mobile sink maintenance | 4 | 27% | 5 | 21% |

| Suspended in-person activities | 2 | 13% | 3 | 13% |

| Solely providing relief aid | 3 | 20% | 3 | 13% |

| TOTAL | 24 | 100% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Curty Pereira, R.; Elliott, S.J.; Llaguno Cárdenas, P. Stepping into the Void: Lessons Learned from Civil Society Organizations during COVID-19 in Rio de Janeiro. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085507

Curty Pereira R, Elliott SJ, Llaguno Cárdenas P. Stepping into the Void: Lessons Learned from Civil Society Organizations during COVID-19 in Rio de Janeiro. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(8):5507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085507

Chicago/Turabian StyleCurty Pereira, Rodrigo, Susan J. Elliott, and Pablo Llaguno Cárdenas. 2023. "Stepping into the Void: Lessons Learned from Civil Society Organizations during COVID-19 in Rio de Janeiro" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 8: 5507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20085507