Abstract

Background: While mindfulness-based interventions targeted toward parents (and families) in the U.S. offer promise for the treatment and prevention of youth psychological disorders, current research has established the underrepresentation of diverse participants in the research literature. The full extent of inequalities in the demographics of participation in parent mindfulness intervention is less understood. Objective: This study aimed to utilize a narrative literature review approach to examine and describe the degree to which research on mindful parenting interventions is inclusive of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) communities, non-clinical samples (no diagnosed disorder), cultural adaptions, and skills specific to parenting. Methods: An electronic database search of US-based studies was undertaken for empirical studies that primarily focused on parent mindfulness interventions, which reported outcomes related to either parenting behaviors or child mental health outcomes. After a full-text review, the search resulted in 34 articles. A narrative literature review of the 34 studies was conducted to assess the inclusion of BIPOC communities, non-clinical samples, cultural adaptions, and skills specific to parenting. Results: This review found notable gaps in the degree to which mindful parenting research (1) included BIPOC populations in study samples; (2) focused on non-clinical samples; (3) adapted interventions to align with the cultural needs of participants; and (4) included the application of mindfulness to enhancing knowledge, skills, and behaviors specific to parenting. Conclusions: Given these gaps in the parent mindfulness literature, greater research attention is needed on mindful parenting interventions targeted toward BIPOC communities with no clinical diagnoses, interventions optimized by cultural adaptations, and explicit applications to parenting.

1. Introduction

The prevalence of mental health disorders among children and adolescents has dramatically risen over the last decade, with mental health disorders occurring among 16–20% of children ages 4 to 11, 20–25% of adolescents ages 12 to 17, and 25–40% of young adults ages 18 to 24 [1]. To address this rising demand for mental health support, there is an urgent need for the expansion of preventative family-centered interventions that can prevent or attenuate emergent mental health issues before diagnoses and clinical interventions are required. Mindfulness—commonly defined as non-judgmental awareness of one’s internal states and surroundings [2]—is receiving increased attention as an impactful intervention modality with treatment and preventative implications. Specifically, mindfulness-based interventions that target parents (i.e., mindful parenting interventions) are a well-researched approach that has the potential to benefit whole families [3].

The common objective of mindful parenting interventions is to promote the practices of present-moment, nonjudgmental awareness, such that parents enhance their stress management skills and emotional regulation in the context of parenting. The structure of these interventions typically includes didactic instruction, in-session exercises, and/or home-based exercises. Mindful parenting interventions can vary in mode of delivery (e.g., mobile app, in-person, etc.), frequency, duration, criteria for participation (e.g., parents only or parents and children), and the degree to which curriculum focuses on the application of parenting behaviors (e.g., disciplining children) [3].

In clinical populations (i.e., participants who have an identified medical or mental health condition), parent mindfulness interventions have shown significant benefits to both parents and children across a range of clinical diagnoses. For example, in parents diagnosed with depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and eating disorders, mindfulness-based interventions have been found to be comparable to standard treatments [4], and mindfulness interventions have been shown to significantly improve parents’ well-being and reduce children’s symptoms of ADHD [5].

However, little evidence exists for the potential benefit of mindful parenting interventions for non-clinical samples (i.e., parents or children without an identified diagnosis). The limited research that does exist in non-clinical samples has shown an association between parent participation in mindful parenting interventions with reduced stress and increased emotion regulation ability for parents [6], both of which contribute significantly to positive parenting behaviors and child development; however, more research is needed to fully evaluate the preventive benefits of mindful parenting interventions, especially for child developmental outcomes.

In addition to the dearth of literature on non-clinical samples, research on parent mindfulness (and mindfulness interventions broadly) has demonstrated a significant underrepresentation of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) participants within sample populations. A review of US-based randomized control trials of mindfulness-based interventions, in general, included 69 studies, of which only one specifically focused on racial/ethnic minority or lower socioeconomic status populations; 13 studies reported no data on race/ethnicity; 11 studies reported only the proportion of White participants; and no studies reported intervention effectiveness for disaggregated racial/ethnic groups [7]. These studies demonstrate that limited research focuses on understanding and expanding the benefits of mindfulness-based interventions for BIPOC communities.

This lack of focus on BIPOC research participants is especially alarming in the context of current evidence suggesting that certain aspects of predominant Western mindfulness teaching are not culturally relevant for certain BIPOC communities [8]. The underrepresentation of BIPOC participation also represents not only how the effectiveness of mindfulness in BIPOC communities is understudied but also highlights the opportunities to optimize the efficacy of mindfulness by adapting interventions to the unique cultural, traditional, and spiritual needs of BIPOC communities [9]. While some researchers may be concerned that modifications to treatment manuals could compromise intervention fidelity, the literature for other manualized treatment modalities asserts that cultural adaptions—such as linguistic or conceptual alterations—enhance the adherence and effectiveness of an intervention [10], suggesting a similar approach could enhance parent mindfulness intervention in BIPOC families.

To address this gap in the literature, researchers need an enhanced understanding of how elements of mindfulness instruction can be adapted to optimize the cultural relevance of a given community context, especially BIPOC communities. This paper aims to qualitatively review the recent literature on parent mindfulness interventions, with a specific focus on non-clinical samples of BIPOC parents and the cultural adaptations within the intervention curriculum. Our goal with this narrative literature review was to better understand four main questions within the parent mindfulness intervention literature: to what extent do recent, U.S.-based studies report (1) the inclusion of BIPOC participants; (2) the inclusion of non-clinical samples; (3) adaptations of curriculum to the cultural context of participants; and (4) interventions that focus on developing specific parenting knowledge, skills, or behaviors? A narrative literature review was selected as the method of review to allow for a descriptive perspective, critical analysis, and synthesis of the current state of the literature focusing on these four key questions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

An electronic search for English-language articles was conducted using the Ovid MEDLINE database. While a narrative literature review does not require the strict search and vetting process of a systematic review [11], our team opted for a systematic review approach to thoroughly capture the available published research. While systematic reviews routinely utilize study quality assessments, especially for reviews focused on clinical evidence, we opted not to use a specific quality assessment, as intervention effectiveness was not the focus of our narrative review. We restricted our search to contemporary literature from the last twenty years (2003–2023). Search terms included combinations of the following terms found anywhere within the record, both as Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords including “mindfulness”, “mindful”, “parents” and “children” (see Appendix A for Concept Table with search terms).

2.2. Screening Criteria

We included only intervention studies that reported empirical data; therefore, we excluded editorials, commentaries, perspective essays, case reports, and all reviews. Our inclusion criteria were further narrowed to include only studies that reported parenting-related outcomes and/or developmental outcomes for children, thereby excluding implementation and quality improvement studies that focused on program operations. Of note, we also reviewed the references within relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses; however, we ultimately excluded all reviews during the screening process.

In addition, our screening criteria distinguished between mindfulness-based interventions (e.g., MBSR—Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction) and mindfulness-informed interventions (e.g., acceptance and commitment therapy). Mindfulness-informed interventions often incorporate mindfulness techniques into existing mental health interventions but do not focus primarily on mindfulness, so we removed all studies utilizing mindfulness-informed intervention. This distinction between mindfulness-informed and mindfulness-based approaches has been used in prior literature [12]. Finally, we excluded studies conducted outside of the U.S. Although a wealth of research has been conducted in other countries, the current study focuses on the racial and cultural composition of the U.S. and does not presume that this context could be applied appropriately to the cultural contexts of other countries.

2.3. Study Selection Process

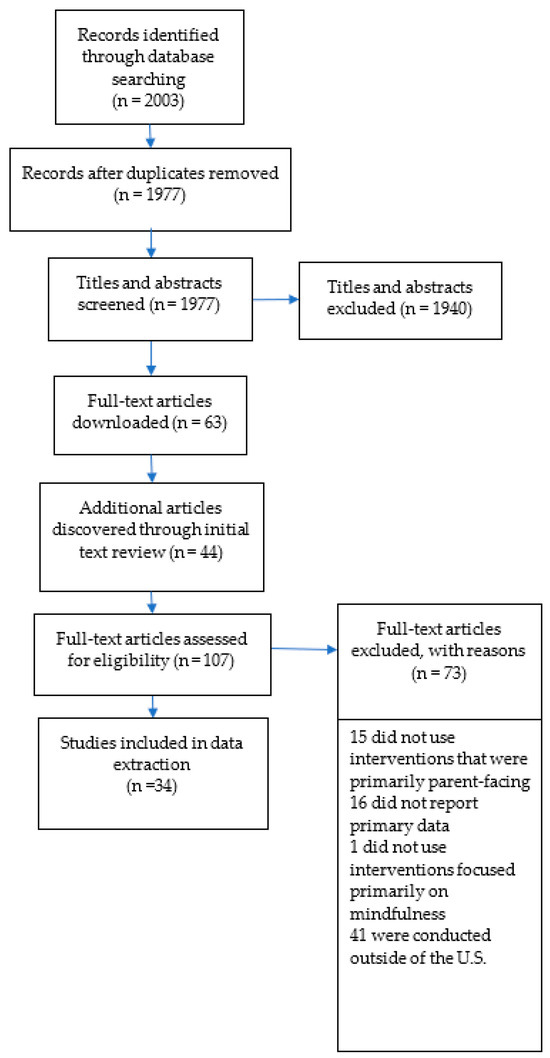

Three independent reviewers (NB, JW, PK) participated in study selection in three general stages: (1) a title review, (2) an abstract review, and (3) a full-text review. The title and abstract reviews were conducted using Rayyan 1.5.0, a systematic review software. All titles assessed as relevant by at least one reviewer were included in the abstract review stages, and all abstracts deemed relevant were included in the full-text review. We utilized team discussions and team consensus to reconcile any disagreement between the three reviewers. At the full-text review stage, only those studies considered relevant by all three reviewers were selected and included for data extraction. During this stage, additional studies were identified by reference reviews of meta-analyses (and systematic reviews) for inclusion in the full-text review (see Figure 1 for flowchart).

Figure 1.

Workflow of the article review process.

2.4. Data Extraction

During the data extraction process, we focused on the degree of inclusion of BIPOC parents by extracting the racial and ethnic demographics that were reported in each study. Next, we extracted data relevant to any non-clinical samples, which we defined as parents/children who are typically developed or parents/children who did not have any identified medical, mental health, or other socioeconomic issues (e.g., homelessness). We also extracted any cultural adaptations reported in the design or delivery of the parent mindfulness interventions. We operationalized cultural adaptation to mean any modifications to the intervention curriculum based on the cultural, social, or historical context of the study population (such as modifications based on linguistic preferences, cultural heritage, spirituality, social needs, cultural values/priorities, etc.). Given this review’s focus on parenting competencies, we extracted data on whether studies applied mindfulness techniques to specific parenting knowledge, skills, and attitudes as well as parent–child interactions (e.g., disciplining children or enhancing parent–child attachment).

3. Results

3.1. General Study Characteristics

A total of 34 articles were identified as being eligible for data extraction for this narrative literature review. Table 1 presents the data extraction from all of the identified studies. The extracted studies were primarily randomized control trials (n = 12, 35% of studies), other quantitative methods (n = 12, 35% of studies), qualitative studies (n = 4, 12%), mixed methods studies (n = 3, 9%) and feasibility studies with preliminary outcome data (n = 3, 9%). Two studies were published as dissertation defenses [13,14]. The sample size of participating parents ranged from 7 to 160. For each included study, reviewers assessed the key areas of interest of the current review, as described below.

Table 1.

Data extraction.

3.2. To What Extent Do Recent Studies Include BIPOC Participants?

A review of the data extracted from each study revealed that all but one study reported at least some data on the race/ethnicity of participants. Twenty studies (59%) reported that the majority of participants identified as White. In terms of reported racial/ethnic demographic data, in 11 studies (32%), the authors presented only the percentage of participants who were White. For instance, Chaplin et al. (2021b) [21] and Duncan et al. (2009) [24] reported that 65% of participants were White and 93% were White, respectively, without reference to the race/ethnicity of the other participants. Fifteen studies (44%) presented data indicating some participation from Black people. For Asian/Pacific Islander participants, 11 studies (32%) presented disaggregated data. Four studies (12%) reported data for American Indian participants. Sixteen studies (47%) reported data for Latine (a gender-neutral term that refers to people of Latin American heritage) participants. Most studies did not report the method by which researchers collected data on race/ethnicity; therefore, it is unknown whether these data were self-reported by participants, assigned by researchers, or based on other data sources.

3.3. To What Extent Do Recent Studies Focus on Non-Clinical Samples?

Six studies (18%) offered a mindful parenting intervention to a non-clinical community sample. The majority, 28 studies (82%), required participating parents or children participants to exhibit clinical symptoms, a diagnosed psychological disorder, or a socioeconomic issue (i.e., poverty/homelessness). Among these problem- or symptom-focused studies, 14 studies (41%) used a diagnosed disorder for the child (i.e., ADHD, ASD, or IDD) as the inclusion criterion. Seven studies (21%) focused on parental symptoms or disorders, consisting of parental stress, anxiety, or SUD/OUD. A smaller subset of studies (n = 3, 9%) focused on parents of children with medical issues requiring hospitalization (i.e., Neonatal Intensive Care Unit). Two studies (6%) focused on parents with physical challenges related to obesity or a genetic condition (i.e., FMR1 premutation) [31,32]. Three studies (9%) focused on parents with socioeconomic challenges of divorce, poverty, and/or homelessness [15,35,46].

3.4. To What Extent Do Recent Studies Include Adaptations of Curriculum According to the Cultural Context of Participants?

No studies reported developing or adapting its intervention to be aligned with the culture of participants. However, a few references were made to adapting the mode of delivery, duration, and frequency of mindful parenting activities to the availability of participants (e.g., busy parents or antepartum women). For example, Doty et al. (2022) [23] utilized a smartphone-based, self-guided mindfulness intervention because it required minimal training and provided maximum flexibility of use, given the attentional demands women experience in an antepartum hospital setting. Another study [24] offered childcare, dinner, and attendance gifts to parents to facilitate participation. Anderson et al. (2015) [16] adapted content to reference the unique life challenges of a child’s psychopathology and discussed how the intervention included applications to the specific challenges of caring for a child with ADHD. No study reported making linguistic alterations according to participants; no studies cited adaptions to the curriculum according to the cultural values and priorities of the participants; and no studies reported any consideration of racial/ethnic concordance between facilitators and participants.

3.5. To What Extent Do Studies Focus on Applying Mindfulness to Knowledge, Skills, and Behaviors Specific to Parenting?

All studies taught core mindfulness practices in some form, such as deep breathing, body awareness, meditation, present-moment awareness, and body scan exercises. Twelve studies (35%) focused solely on the practice of mindfulness for the individual participants and offered no specific or intentional reference to how this practice applies to parenting knowledge, skills, or behaviors. Twenty-two studies (65%) explicitly included applications to parenting in their intervention description. For example, several studies included an explicit focus on the mindful parenting capacities of listening with full attention; emotional awareness of, acceptance of, and compassion for self and child; and self-regulation in parenting [22,24,43]. One intervention went so far as to engage with parent/child dyads in mindful and intentional play while providing real-time feedback on parenting behaviors [28].

4. Discussion

This narrative literature review sought to describe the U.S. landscape of parent mindfulness research with a specific focus on the participation of BIPOC, intervention adaptions based on culture or parenting, and non-clinical samples. In summary, several gaps in the literature became apparent from this narrative literature review. Overall, we found a significant underrepresentation of both BIPOC and non-clinical samples, a lack of research on cultural adaptations of curriculum, and a dearth of studies that specifically employ mindfulness curricula that target parenting-related competencies.

With regards to sample representative diversity, over half of studies reported that a majority of participants identified as White, and almost a third of studies reported participation data for White participants only. Several factors may be driving a sampling and reporting phenomena that favor White-identifying participants. For one, prior research has shown that many intervention studies take place in hospitals, clinics, or university settings that have existing racial disparities in access to services [47]; thus, potential participant pools are limited to predominantly White samples. Plus, traditional non-participatory research designs (e.g., RCTs) typically do not involve significant community outreach efforts to engage participants who have been historically excluded from intervention studies [48]. Further, the fact that only 18% offered a mindful parenting intervention to a non-clinical community sample indicates that mindful parenting interventions are primarily researched as clinical interventions in response to diagnosed disorders rather than a public health approach to the prevention of illness or promotion of healthy child development and family functioning.

This narrative literature review did not identify any studies that developed or adapted an intervention in alignment with the cultural identity of the participants. We speculate that this gap in the literature may represent researchers’ tendency to prioritize standardized training content in the interest of preserving intervention fidelity. Further, this gap may reflect a lack of consideration among researchers that participant cultural identity can play an important role in the acceptance, adherence, and efficacy of the mindfulness intervention. In the broader psychosocial intervention literature, interventions like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) have shown robust results with cultural adaptations, including linguistic modifications [10]. Also, current evidence suggests that the culture of study participants—specifically BIPOC parents—plays an important role in the feasibility and acceptability of mindful parenting interventions [8,49], and the bias embedded in standardized research protocols (designed to advance generalizable interventions) can come at the cost of cultural and local specificity.

Cultural adaption can present implementation challenges for researchers and practitioners, especially given that cultural traditions within a population are heterogeneous and fluid. Guidance for navigating these challenges can be drawn from a wealth of literature on participatory research approaches, such as community-based participatory research (CBPR). CBPR approaches have demonstrated how interventions can be culturally adapted while maintaining adequate fidelity and enhancing intervention efficacy [50]. Plus, this team has published data elsewhere [49,51,52], suggesting how CBPR in the context of mindfulness interventions can lead to cultural adaption and innovations in curriculum, outcome measures, and data interpretation.

The fact that only approximately two-thirds of the studies included explicit applications to parenting in their intervention curriculum raises an important question regarding the design of mindful parenting interventions. While decades of empirical scholarship have built a strong case for developing individual mindfulness practices that promote general wellness among parents, which in turn promote positive parenting [4], explicit training on applying mindfulness concepts and practices to parenting behaviors is under-studied. Emphasizing specific applications of mindfulness to parenting can potentially enhance the impact of mindful parenting training on parent–child interactions, thus, fostering healthy child development. Future studies should explore how explicit application to parenting through activities, such as applying present-moment awareness to interactions with children, or during play, can improve child development and other metrics of family well-being.

Several limitations emerged throughout this review, which may have impacted the findings. Notably, the specificity of our aims required the exclusion of many studies related to mindful parenting that may have offered additional observations. The exclusion of international studies did not allow for the examination of research in non-U.S. contexts, and the focus on mindfulness-based (vs. mindfulness-inspired) interventions led to the exclusion of some parent-involved research related to mindfulness that could have yielded additional insights. Finally, the majority of the selected studies did not include detailed descriptions of the mindfulness curriculum that was utilized, which may have contributed to an under-recognition of specific cultural adaptations or parenting applications in the interventions, but were not fully described within published articles.

5. Conclusions

Mindful parenting interventions offer great promise as a whole-family and preventative approach to ameliorating emergent youth mental health challenges. This review has revealed that both the potential preventative benefits and the benefits within parent–child interactions for mindful parenting interventions are understudied areas. These interventions need not be restricted to clinically treated populations, and they can be made more broadly available to families through a public health approach, serving families in educational, recreational, religious, and broader community settings. And, to ensure BIPOC communities benefit from these interventions, cultural adaptations, and targeted community engagement strategies should be developed, implemented, and evaluated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.W., N.B. and J.H.; methodology, J.C.W., P.K., N.B. and K.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.W. and N.B.; writing—review and editing, J.C.W., P.K., N.B. and K.G.; supervision, J.C.W. and N.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, J.C.W, upon reasonable request. Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the dedication of the parent mindfulness team at the Early Childhood Innovation Network (ECIN) in Washington, DC.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Concept Table for Database Search Strategy

| Mindfulness [Concept A] | Parenting [Concept B] | Child Mental Health [Concept C] |

| Key Words | ||

| Mindfulness Relational mindfulness Meditation Mindful parenting Awareness Self-compassion Cognitive therapy Family-based intervention Parenting intervention | Parents Parenting Parenting behaviors Personal satisfaction Parent well-being Parenting stress Attachment Psychopathology Marital functioning Co-parenting Relationship quality Parent–child dyads Parent–child relations Interpersonal relations | Depression Anxiety Externalization Internalization Psychopathology Challenging behavior Adolescence Child internalizing Child externalizing Internal–external control |

| MeSH | ||

|

|

|

References

- Bai, M.S.; Miao, C.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Jia, F.Y.; Du, L. COVID-19 and mental health disorders in children and adolescents (Review). Psychiatry Res. 2022, 317, 114881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life; Hachette Books: New York, NY, USA, 1994; 132p. [Google Scholar]

- Townshend, K.; Jordan, Z.; Stephenson, M.; Tsey, K. The effectiveness of mindful parenting programs in promoting parents’ and children’s wellbeing: A systematic review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2016, 14, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgdorf, V.; Szabó, M.; Abbott, M.J. The Effect of Mindfulness Interventions for Parents on Parenting Stress and Youth Psychological Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiri, M.; Fatemi, S.A.M.; Jabbari, S.; Nesayan, A.; Farmani, P. The effectiveness of mindful parenting training on attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in male students. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Corthorn, C.; Milicic, N. Mindfulness and Parenting: A Correlational Study of Non-meditating Mothers of Preschool Children. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 1672–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, E.M.; Hong, S.; Moskowitz, J.T.; Burnett-Zeigler, I. A Systematic Review of the Demographic Characteristics of Participants in US-Based Randomized Controlled Trials of Mindfulness-Based Interventions. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 1671–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, N.N.; Black, A.R.; Hunter, C.D. African American Women’s Perceptions of Mindfulness Meditation Training and Gendered Race-Related Stress. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S. Mindfulness: Towards A Critical Relational Perspective. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2012, 6, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, S.I.; Romano, M.; Hudson, J.L. A Comparison of Interactions Among Children, Parents, and Therapists in Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Anxiety Disorders in Australia and Japan. Behav. Ther. 2022, 53, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, R.S.; Brewer, J.; Feldman, C.; Kabat-Zinn, J.; Santorelli, S.; Williams, J.M.G.; Kuyken, W. What defines mindfulness-based programs? The warp and the weft. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voos, A.C. An Initial Evaluation of the Mindful Parenting Group for Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1990616153/abstract/289119BA97CE40A8PQ/1 (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Xu, Y. Parental Stress, Emotion Regulation, Meta-Emotion, and Changes Following an MBSR Intervention. Ph.D. Thesis, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2002542936/abstract/8D50EF1069D94CB8PQ/1 (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Alhusen, J.L.; Norris-Shortle, C.; Cosgrove, K.; Marks, L. I’m opening my arms rather than pushing away: Perceived benefits of a mindfulness-based intervention among homeless women and young children. Infant. Ment. Health J. 2017, 38, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, S.B.; Guthery, A.M. Mindfulness-based psychoeducation for parents of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: An applied clinical project. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2015, 28, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzano, A.; Wolfe, C.; Zylowska, L.; Wang, S.; Schuster, E.; Barrett, C.; Lehrer, D. Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) for Parents and Caregivers of Individuals with Developmental Disabilities: A Community-Based Approach. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.M.; Chan, N.; Neece, C.L. Parent Perspectives of Applying Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Strategies to Special Education. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 55, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.K.C.; Zhang, D.; Bögels, S.M.; Chan, C.S.; Lai, K.Y.C.; Lo, H.H.M.; Yip, B.H.K.; Lau, E.N.S.; Gao, T.T.; Wong, S.Y.S. Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention (MYmind) for children with ADHD and their parents: Protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, T.M.; Turpyn, C.C.; Fischer, S.; Martelli, A.M.; Ross, C.E.; Leichtweis, R.N.; Miller, A.B.; Sinha, R. Parenting-Focused Mindfulness Intervention Reduces Stress and Improves Parenting in Highly Stressed Mothers of Adolescents. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, T.M.; Mauro, K.L.; Curby, T.W.; Niehaus, C.; Fischer, S.; Turpyn, C.C.; Martelli, A.M.; Miller, A.B.; Leichtweis, R.N.; Baer, R.; et al. Effects of A Parenting-Focused Mindfulness Intervention on Adolescent Substance Use and Psychopathology: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Res. Child. Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2021, 49, 861–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coatsworth, J.D.; Duncan, L.G.; Nix, R.L.; Greenberg, M.T.; Gayles, J.G.; Bamberger, K.T.; Berrena, E.; Demi, M.A. Integrating mindfulness with parent training: Effects of the Mindfulness-Enhanced Strengthening Families Program. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doty, M.S.; Chen, H.Y.; Ajishegiri, O.; Sibai, B.M.; Blackwell, S.C.; Chauhan, S.P. Daily meditation program for anxiety in individuals admitted to the antepartum unit: A multicenter randomized controlled trial (MEDITATE). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2022, 4, 100562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, L.G.; Coatsworth, J.D.; Greenberg, M.T. Pilot study to gauge acceptability of a mindfulness-based, family-focused preventive intervention. J. Prim. Prev. 2009, 30, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felver, J.; Tipsord, J.; Morris, M.; Racer, K.; Dishion, T. The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Children’s Attention Regulation. J. Atten. Disord. 2014, 21, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraioli, S.J.; Harris, S.L. Comparative Effects of Mindfulness and Skills-Based Parent Training Programs for Parents of Children with Autism: Feasibility and Preliminary Outcome Data. Mindfulness 2013, 4, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, M.; Mackenzie, M.; Kaltenbach, K.; Abatemarco, D. Impact of Mindfulness-Based Parenting on Women in Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder. J. Addict. Med. 2017, 11, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gannon, M.; Mackenzie, M.; Short, V.; Reid, L.; Hand, D.; Abatemarco, D. “You can’t stop the waves, but you can learn how to surf”: Realized mindfulness in practice for parenting women in recovery. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2022, 47, 101549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.H.; Guarino, A.; Chenausky, K.; Klein, L.; Prager, J.; Petersen, R.; Forget, A.; Freeman, M. CALM Pregnancy: Results of a pilot study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for perinatal anxiety. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2014, 17, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, C.H.; Stephens, R.L.; Ratliff, M.L.; Short, S.J. Parent-Child Mindfulness-Based Training: A Feasibility and Acceptability Study. J. Evid. Based Integr. Med. 2021, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.E.; Jenkins, C.L.; Grim, V.; Leung, S.; Charen, K.H.; Hamilton, D.R.; Allen, E.G.; Sherman, S.L. Feasibility of an app-based mindfulness intervention among women with an FMR1 premutation experiencing maternal stress. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 89, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff, A.M.; Chaplin, T.M.; Finnie, S.; Savoye, M.; Stults-Kolehmainen, M.; Silverman, W.K.; Sinha, R. Preventing Childhood Obesity Through a Mindfulness-Based Parent Stress Intervention: A Randomized Pilot Study. J. Pediatr. 2018, 202, 136–142.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantrowitz-Gordon, I.; Abbott, S.; Hoehn, R. Experiences of Postpartum Women after Mindfulness Childbirth Classes: A Qualitative Study. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2018, 63, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewallen, A.C.; Neece, C.L. Improved Social Skills in Children with Developmental Delays After Parent Participation in MBSR: The Role of Parent–Child Relational Factors. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 3117–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, R.; Altmaier, E. An initial evaluation of a mindful parenting program. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 63, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marshall, A.; Guillen, U.; Mackley, A.; Sturtz, W. Mindfulness Training among Parents with Preterm Neonates in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Pilot Study. Am. J. Perinatol. 2019, 36, 1514–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendelson, T.; McAfee, C.; Damian, A.J.; Brar, A.; Donohue, P.; Sibinga, E. A mindfulness intervention to reduce maternal distress in neonatal intensive care: A mixed methods pilot study. Arch. Women Ment. Health 2018, 21, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neece, C.L. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Parents of Young Children with Developmental Delays: Implications for Parental Mental Health and Child Behavior Problems. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2014, 27, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noroña-Zhou, A.N.; Coccia, M.M.; Epel, E.; Vieten, C.; Adler, N.E.; Laraia, B.; Jones-Mason, K.J.; Alkon, A.; Bush, N.R. The Effects of a Prenatal Mindfulness Intervention on Infant Autonomic and Behavioral Reactivity and Regulation. Psychosom. Med. 2022, 84, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petteys, A.R.; Adoumie, D. Mindfulness-Based Neurodevelopmental Care: Impact on NICU Parent Stress and Infant Length of Stay; A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Adv. Neonat. Care 2018, 18, E12–E22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.R.; Neece, C.L. Feasibility of Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction Intervention for Parents of Children with Developmental Delays. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 36, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, L.R.; Boostrom, G.G.; Dehom, S.O.; Neece, C.L. Self-Reported Parenting Stress and Cortisol Awakening Response Following Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Intervention for Parents of Children With Developmental Delays: A Pilot Study. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2020, 22, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, V.L.; Gannon, M.; Weingarten, W.; Kaltenbach, K.; LaNoue, M.; Abatemarco, D.J. Reducing Stress Among Mothers in Drug Treatment: A Description of a Mindfulness Based Parenting Intervention. Matern. Child. Health J. 2017, 21, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitlauf, A.S.; Broderick, N.; Stainbrook, J.A.; Taylor, J.L.; Herrington, C.G.; Nicholson, A.G.; Santulli, M.; Dykens, E.M.; Juárez, A.P.; Warren, Z.E. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Parents Implementing Early Intervention for Autism: An RCT. Pediatrics 2020, 145 (Suppl. S1), S81–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weitlauf, A.S.; Broderick, N.; Alacia Stainbrook, J.; Slaughter, J.C.; Taylor, J.L.; Herrington, C.G.; Nicholson, A.G.; Santulli, M.; Dorris, K.; Garrett, L.J.; et al. A Longitudinal RCT of P-ESDM With and Without Parental Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction: Impact on Child Outcomes. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 5403–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Emory, E.K. A mindfulness-based intervention for pregnant African-American women. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Tsai, J.; Higgins, P.C.; Lebrun, L.A. Racial/Ethnic and Socioeconomic Disparities in Access to Care and Quality of Care for US Health Center Patients Compared With Non–Health Center Patients. J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2009, 32, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain-Gambles, M.; Atkin, K.; Leese, B. Why ethnic minority groups are under-represented in clinical trials: A review of the literature. Health Soc. Care Community 2004, 12, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathis, E.T.; Hawkins, J.; Charlot-Swilley, D.; Spencer, T.; Lingo, K.J.; Trachtenberg, D.; McPherson, S.K.L.; Domitrovich, C.E.; Shapiro, A.; Williams, J.C.; et al. Mindfulness Intervention with African-American Caregivers at a Head Start Program: An Acceptability and Feasibility Study. Mindfulness 2024. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.; Trickett, E.J. Collaborative Measurement Development as a Tool in CBPR: Measurement Development and Adaptation within the Cultures of Communities. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2014, 54, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, A., Jr.; Gavins, A.; Watson, A.; Domitrovich, C.E.; Oruh, C.M.; Morris, C.; Boogaard, C.; Sherwood, C.; Sharp, D.N.; Charlot-Swilley, D.; et al. Advancing Antiracism in Community-Based Research Practices in Early Childhood and Family Mental Health. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 61, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.; Williams, J.C.; Bravo, N.; McPherson, S.K.; Spencer, T.; Charlot-Swilley, D.; Domitrovich, C.E.; Biel, M.G. Evolving Toward Community-Based Participatory Research: Lessons Learned from a Mindful Parenting Project. Mindfulness 2024. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).