Internalized Sexual Stigma and Mental Health Outcomes for Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Asian Americans: The Moderating Role of Guilt and Shame

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Minority Stress Theory and Internalized Sexual Stigma

1.2. ISS at the Intersection of Sexuality and Ethnicity

1.3. Internalized Sexual Stigma for Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Asians

1.4. Aims and Hypotheses

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Characteristics

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Predictor Variables

2.3.2. Mental Health Outcome Variables

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Data Preparation and Screening

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Univariable Analysis

3.3. Mental Health Classifications

3.4. Mediation Analyses

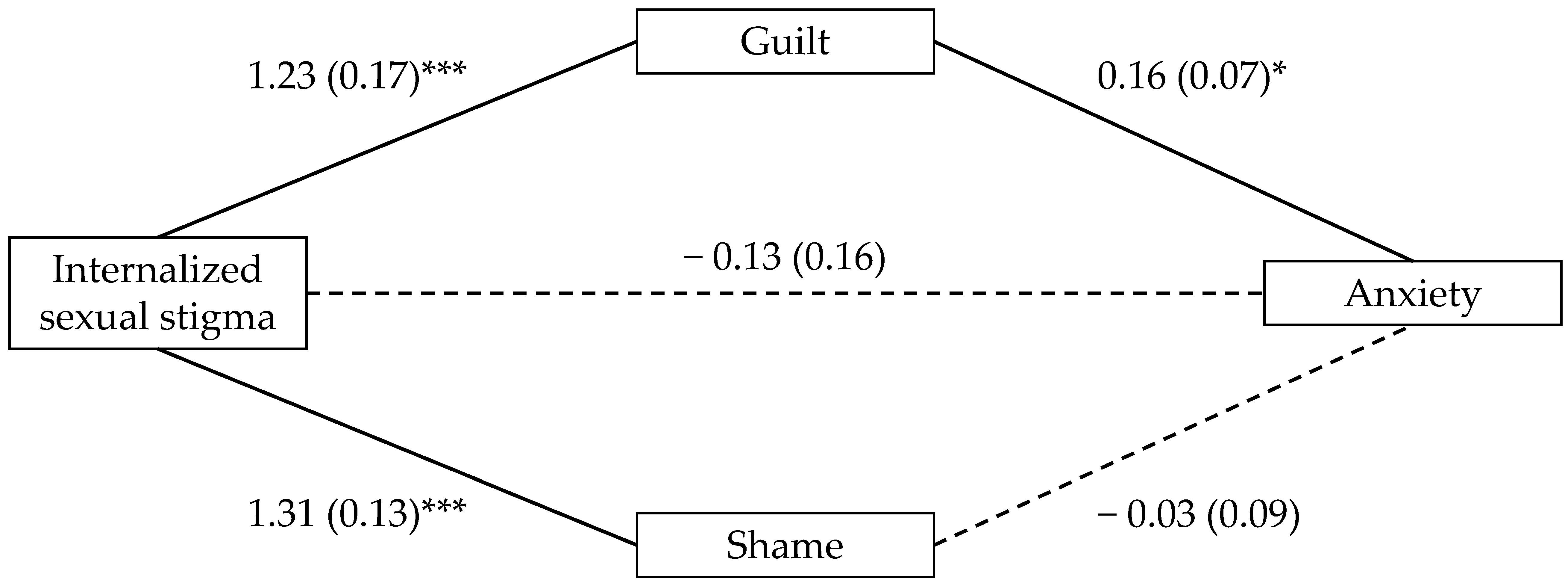

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Major Findings

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

4.3. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- James, S.; Herman, J.; Rankin, S.; Keisling, M.; Mottet, L.; Anafi, M. The Report of the 2015 US Transgender Survey; National Centre for Transgender Equality: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Medley, G.; Lipari, R.N.; Bose, J.; Cribb, D.S.; Kroutil, L.A.; McHenry, G. Sexual orientation and estimates of adult substance use and mental health: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH Data Rev. 2016, 10, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, T.; Bourne, A.; Amos, N.; Power, J.; Anderson, J.; Lim, G.; Carman, M.; Meléndez-Torres, G. Typologies of alcohol and other drug-related risk among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (trans) and queer adults. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2024, 43, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Trevor Project. National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health; The Trevor Project: West Hollywood, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Mental Health Commission. Monitoring Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Reform: National Report 2019; National Mental Health Commission: Sydney, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I.H. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, D.M.; Kashubeck-West, S.; Meyer, J. Internalized heterosexism: A historical and theoretical overview. Couns. Psychol. 2008, 36, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, D.M. Does internalized heterosexism moderate the link between heterosexist events and lesbians’ psychological distress? Sex Roles 2006, 54, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.A.; Pereira, H.; Leal, I. Internalized homonegativity, disclosure, and acceptance of sexual orientation in a sample of Portuguese gay and bisexual men, and lesbian and bisexual women. J. Bisex. 2013, 13, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, V.; Robert-McComb, J.J.; Clopton, J.R.; Reich, D.A. Investigating the influence of shame, depression, and distress tolerance on the relationship between internalized homophobia and binge eating in lesbian and bisexual women. Eat. Behav. 2017, 24, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.; Anderson, J.; Pepping, C.A. A systematic review and research agenda of internalized sexual stigma in sexual minority individuals: Evidence from longitudinal and intervention studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 108, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, D.N.; Mirzayi, C.; Rendina, H.J.; Ventuneac, A.; Grov, C.; Parsons, J.T. Mediating effects of social support and internalized homonegativity on the association between population density and mental health among gay and bisexual men. LGBT Health 2017, 4, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, A.; Pepping, C.A. Prospective effects of social support on internalized homonegativity and sexual identity concealment among middle-aged and older gay men: A longitudinal cohort study. Anxiety Stress Coping 2017, 30, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, M.; Pistella, J.; Ioverno, S.; Laghi, F.; Baiocco, R. Coming out to siblings and internalized sexual stigma: The moderating role of gender in a sample of Italian participants. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2018, 14, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, Y.; Sahin, H.; Garner, A.; Anderson, J.R. Societal acceptance increases Muslim-Gay identity integration for highly religious individuals… but only when the ingroup status is stable. Self Identity 2022, 21, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, J.D.; De la Piedad Garcia, X.; Kaufmann, L.M.; Koc, Y.; Anderson, J.R. A systematic and meta-analytic review of identity centrality among LGBTQ groups: An assessment of psychosocial correlates. J. Sex Res. 2022, 59, 568–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, R.C.; Ross, M.W.; Weatherburn, P.; Schmidt, A.J. Structural and environmental factors are associated with internalised homonegativity in men who have sex with men: Findings from the European MSM Internet Survey (EMIS) in 38 countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 78, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K.W. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. In The Public Nature of Private Violence; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, E.R. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, A.K.J.; Johnson, A.N.; Clockston, R.; Oselinsky, K.; Lundeberg, P.J.; Rand, K.; Graham, D.J. Intersectional health disparities: The relationships between sex, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation and depressive symptoms. Psychol. Sex. 2022, 13, 1068–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, K.; Salter, N.; Thoroughgood, C. Studying individual identities is good, but examining intersectionality is better. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 6, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocco, R.; Laghi, F.; Di Pomponio, I.; Nigito, C.S. Self-disclosure to the best friend: Friendship quality and internalized sexual stigma in Italian lesbian and gay adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspal, R.; Lopes, B.; Rehman, Z. A structural equation model for predicting depressive symptomatology in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic gay, lesbian and bisexual people in the UK. Psychol. Sex. 2021, 12, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, M.; Perrin, P.B. Discrimination, mental health, and suicidal ideation among LGBTQ people of color. J. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 63, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymanski, D.M.; Gupta, A. Examining the relationships between multiple oppressions and Asian American sexual minority persons’ psychological distress. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2009, 21, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangani, S.; Gamarel, K.E.; Ogunbajo, A.; Cai, J.; Operario, D. Intersectional minority stress disparities among sexual minority adults in the USA: The role of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Cult. Health Sex. 2020, 22, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.J.; Anderson, J.R. Systematic literature review and meta-analysis of the impacts of internalised sexual stigma for lesbian, gay, and bisexual Asians. J. Homosex. 2024; Manuscript under review. [Google Scholar]

- Cyrus, K. Multiple minorities as multiply marginalized: Applying the minority stress theory to LGBTQ people of color. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2017, 21, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giwa, S.; Greensmith, C. Race relations and racism in the LGBTQ community of Toronto: Perceptions of gay and queer social service providers of color. J. Homosex. 2012, 59, 149–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.J.; Anderson, J.R.; Amos, N.; de la Piedad Garcia, X.; Thai, M.; Bourne, A. Health and Wellbeing at the Intersection of Gender Identity and Ethnicity in Australia. Int. J. Transgender Health, 2024; Manuscript under review. [Google Scholar]

- Krehely, J. How to Close the LGBT Health Disparities Gap: Disparities by Race and Ethnicity; Centre for American Progress: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, C.; Tan, R.K.J.; Le, D.; Tan, A.; Tyler, A.; Tan, C.; Kwok, C.; Banerjee, S.; Wong, M.L. Association between sexual orientation acceptance and suicidal ideation, substance use, and internalised homophobia amongst the pink carpet Y cohort study of young gay, bisexual, and queer men in Singapore. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 971–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaspal, R. Honour beliefs and identity among British South Asian gay men. In Men, Masculinities and Honour-Based Abuse; Idriss, M., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 114–127. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.-T.; Chan, R.C.H.; Cui, L. Filial piety, internalized homonegativity, and depressive symptoms among Taiwanese gay and bisexual men: A mediation analysis. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2020, 90, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Chui, H.; Chung, M.C. The moderating effect of filial piety on the relationship between perceived public stigma and internalized homophobia: A national survey of the Chinese LGB population. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2021, 18, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, D.M.; Sung, M.R. Asian cultural values, internalized heterosexism, and sexual orientation disclosure among Asian American sexual minority persons. J. LGBT Issues Couns. 2013, 7, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.A.; Chung, Y.B.; Dean, J.K. Acculturation level and internalized homophobia of Asian American lesbian and bisexual women: An exploratory analysis. J. LGBT Issues Couns. 2007, 1, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, N.L. The Role of Masculinity-Based Stress and Minority Stress in the Mental Health of Asian and Pacific Islander Gay and Bisexual Men in the US. Ph.D. Thesis, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, H.B. Shame and guilt in neurosis. Psychoanal. Rev. 1971, 58, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bybee, J.A.; Sullivan, E.L.; Zielonka, E.; Moes, E. Are gay men in worse mental health than heterosexual men? The role of age, shame and guilt, and coming-out. J. Adult Dev. 2009, 16, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R.; Kiernan, E.; Koc, Y. The protective role of identity integration against internalized sexual prejudice for religious gay men. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2023, 15, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, B.; van den Berg, J.J.; Epting, F.R. Threat and guilt aspects of internalized antilesbian and gay prejudice: An application of personal construct theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2009, 56, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Angelique, H. Internalized homonegativity, Confucianism, and self-esteem at the emergence of an LGBTQ identity in modern Vietnam. J. Homosex. 2017, 64, 1617–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, P.K.-Y.; Cheng, S.-T. Shame, internalized heterosexism, lesbian identity, and coming out to others: A comparative study of lesbians in mainland China and Hong Kong. J. Couns. Psychol. 2010, 57, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, Z.; Jaspal, R.; Fish, J. Service provider perspectives of minority stress among black, asian and minority ethnic lesbian, gay and bisexual people in the UK. J. Homosex. 2021, 68, 2551–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Low, W.Y.; Tai, R.; Tong, W.T. Shame, internalized homonegativity, and religiosity: A comparison of the stigmatization associated with minority stress with gay men in Australia and Malaysia. Int. J. Sex. Health 2016, 28, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaffoni, S.; Koc, Y.; Monreal, D.C.; González, R.; Roblain, A.; Hanioti, M.; Anderson, J.R. Reconceptualizing internalised sexual prejudice: Self- Vs. Ingroup-related prejudice has different antecedents and consequences for identity, sexuality, and well-being for gay men. In Proceedings of the European Congress of Social Psychology, Krakow, Poland, 24–27 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.R.; Koc, Y. Identity integration as a protective factor against guilt and shame for religious gay men. J. Sex Res. 2020, 57, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, E.M.; Malmgren, J.A.; Carter, W.B.; Patrick, D.L. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1994, 10, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.T.; Chan, A.C. The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale in older Chinese: Thresholds for long and short forms. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 20, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boey, K.W. Cross-validation of a short form of the CES-D in Chinese elderly. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1999, 14, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer, R.; Spitzer, R. Edited correspondence on the status of homosexuality in DSM-III. J. Hist. Behav. Sci. 1982, 18, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberti, J.W.; Harrington, L.N.; Storch, E.A. Further psychometric support for the 10-item version of the perceived stress scale. J. Coll. Couns. 2006, 9, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling; University of Kansas: Lawrence, KS, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarroel, M.A.; Terlizzi, E.P. Symptoms of Depression among Adults: United States, 2019; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Terlizzi, E.P.; Villarroel, M.A. Symptoms of Generalized Anxiety Disorder among Adults: United States, 2019; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Herek, G.M.; Cogan, J.C.; Gillis, J.R.; Glunt, E.K. Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men. Gay Lesbian Med. Assoc. 1998, 2, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, S. The interrelations between internalized homophobia, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among Australian gay men, lesbians, and bisexual women. J. Homosex. 2016, 63, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, P.B.; Sutter, M.E.; Trujillo, M.A.; Henry, R.S.; Pugh, M., Jr. The minority strengths model: Development and initial path analytic validation in racially/ethnically diverse LGBTQ individuals. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benet-Martínez, V.; Leu, J.; Lee, F.; Morris, M.W. Negotiating biculturalism: Cultural frame switching in biculturals with oppositional versus compatible cultural identities. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2002, 33, 492–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, Y.; Vignoles, V. Global identification helps increase identity integration among Turkish gay men. Psychol. Sex. 2018, 9, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.M.; Simon, K.A.; Henicheck, J. The relationship between sexuality–professional identity integration and leadership in the workplace. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2018, 5, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Bhundia, R.; Mitra, R.; McEwan, K.; Irons, C.; Sanghera, J. Cultural differences in shame-focused attitudes towards mental health problems in Asian and non-Asian student women. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2007, 10, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonov, A.A.; Espinosa, A.; Huynh, Q.-L.; Anglin, D.M. Bicultural identity harmony and American identity are associated with positive mental health in US racial and ethnic minority immigrants. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2019, 25, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siraj, A. “I don’t want to taint the name of Islam”: The influence of religion on the lives of Muslim lesbians. J. Lesbian Stud. 2012, 16, 449–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I.H. Identity, Stress, and Resilience in Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals of Color. Couns. Psychol. 2010, 38, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | Correlations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |||

| 1. ISS | 2.17 | 0.59 | 0.52 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| 2. Guilt | 2.10 | 1.39 | – | 0.71 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.18 * | 0.19 * |

| 3. Shame | 2.12 | 1.20 | – | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.08 | |

| 4. Depression | 1.39 | 0.67 | – | 0.85 ** | 0.81 ** | ||

| 5. Anxiety | 1.39 | 0.87 | – | 0.78 ** | |||

| 6. Stress | 2.21 | 0.76 | – | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, K.J.; Anderson, J.R. Internalized Sexual Stigma and Mental Health Outcomes for Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Asian Americans: The Moderating Role of Guilt and Shame. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040384

Tan KJ, Anderson JR. Internalized Sexual Stigma and Mental Health Outcomes for Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Asian Americans: The Moderating Role of Guilt and Shame. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(4):384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040384

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Kian Jin, and Joel R. Anderson. 2024. "Internalized Sexual Stigma and Mental Health Outcomes for Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Asian Americans: The Moderating Role of Guilt and Shame" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 4: 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040384

APA StyleTan, K. J., & Anderson, J. R. (2024). Internalized Sexual Stigma and Mental Health Outcomes for Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Asian Americans: The Moderating Role of Guilt and Shame. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(4), 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040384