Abstract

(1) Background: During pregnancy, changes in foot biomechanics affect structural stability and gait. (2) Objective: To map the available evidence for changes in foot biomechanics during pregnancy and the postpartum period. (3) Methods: Scoping review according to the methodology of the Joanna Briggs Institute through the relevant databases via EBSCO, MEDLINE with full text, BioOne Complete, CINAHL Plus with full text, Academic Search Complete, and SPORT Discus with full text. The search was conducted in SCOPUS and PubMed. (4) Results: Eight studies were included in the scoping review. Two independent reviewers performed data extraction and synthesized data in narrative form. We found that changes in the length and volume of the foot occur during pregnancy and remain in the postpartum period. (5) Conclusions: During pregnancy, anatomical and biomechanical changes occur in the pregnant woman’s foot, potentially contributing to the risk of musculoskeletal disorders. However, more research is needed to determine whether these biomechanical changes can lead to the risk of musculoskeletal disorders.

1. Introduction

Pregnancy is a specific period in a woman’s life where several hormonal and physiological changes occur [1], including weight gain, unevenly distributed body mass, and an altered center of gravity [2]. These changes impact the distribution of plantar pressures, forces, and other foot characteristics [3,4], and the pregnant woman needs to adapt to maintain structural and gait stability [4,5]. From a biomechanical point of view, the gravid uterus shifts the center of gravity forward, increasing the lumbar lordosis, moving the base of support (feet) away, and altering the gait [6,7]. In addition, endocrine changes cause relaxation of the ligaments that support the arch and consequent loss of height in the arch of the foot [8].

Thus, the foot, the most distal structure in the human body and an essential element of gait, undergoes several changes during pregnancy [5,9,10].

Due to the change in the pregnant woman’s body configuration, i.e., as the fetus develops, the position of the woman’s center of gravity moves superiorly and anteriorly, more significant pressure is applied to the forefoot areas during standing, and anteroposterior sway becomes prominent [11]. Also, a compensatory anti-fall mechanism that decreases lateral sway has been reported, such as an increase in support width in pregnant women [11].

Lower frequency and smaller steps also characterize the gait pattern throughout pregnancy, translating into longer support time and greater support width, which are compensated by the medial–lateral component of the vertical reaction force [12,13]. In addition, there is an increase in anterior pelvic tilt, overload on the hip joint, and higher plantar loads on the midfoot and forefoot [12].

These changes have always been considered during pregnancy and are increasingly so in the postpartum period. In other words, women are increasingly the main agents in promoting their well-being and enjoying physical and emotional recovery. Evidence shows that women are more affected by musculoskeletal disorders than men and that this may, in part, be related to the biochemical changes that occur in the woman’s body during pregnancy [8]. Thus, whether these changes return to baseline values or persist after childbirth is as essential—if not more so—than the changes in the feet reported during pregnancy.

Therefore, it is important to explore how the foot’s biomechanics are modified throughout pregnancy to understand the mechanisms, identify possible complications, and develop effective prevention and intervention strategies [8,11,14].

This review aims to map the available evidence on changes in foot biomechanics during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a scoping review using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology [15]. The OSF https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/36FM9 (accessed on 11 May 2024) is the registered title of the review.

Considering the topic, the authors established the following question:

What changes in foot biomechanics are observed during pregnancy and postpartum?

Components of the PPC question include the following:

P (population)—Pregnant and postpartum women;

C (concept)—Biomechanical changes in the foot;

C (context)—Pregnancy and postpartum period.

2.1. Criteria for Eligibility

Population:

Studies whose participants were pregnant, regardless of gestational age, were included, i.e., studies referring to the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd trimesters of pregnancy. We also found studies whose population was women up to one year postpartum. We only included studies with pregnant or postpartum women over the age of 18 years.

Concept:

The various biomechanical changes that occur in the foot during pregnancy and postpartum, namely, increases in the length, width, and volume of the foot, are an integral part of the concept. We also considered the concept of the foot’s center of pressure and musculoskeletal conditions.

Context:

This review considers all anatomical and biomechanical changes in the foot in the context of pregnancy and the postpartum period.

Types of studies/sources:

This review considered quantitative and qualitative studies and systematic reviews. Quantitative designs include any experimental study design (including randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials, or other quasi-experimental studies such as before–after intervention) and observational studies (descriptive, cohort, cross-sectional, case, and case series studies). Qualitative designs include any studies that focus on qualitative data, such as, but not limited to, phenomenology, grounded theory, and ethnography designs, among others.

2.2. Research Strategy and Databases

We developed the research strategy in three stages. First, we conducted an initial limited exploratory search in PubMed to identify articles on the topic. The authors used text words in the titles and abstracts of the relevant articles, and index terms were used to describe the articles falling within the subject under study to develop an advanced search strategy (Table 1). The search strategy, including all the keywords and index terms identified, was adapted for each database, as shown in Table 1. Finally, the reviewers screened the bibliographical references of the included studies. As a limiting factor, the reviewers decided that studies published in English, Portuguese, or Spanish would be included, with no date limit.

Table 1.

Search strategy in the different databases.

2.3. Study Selection

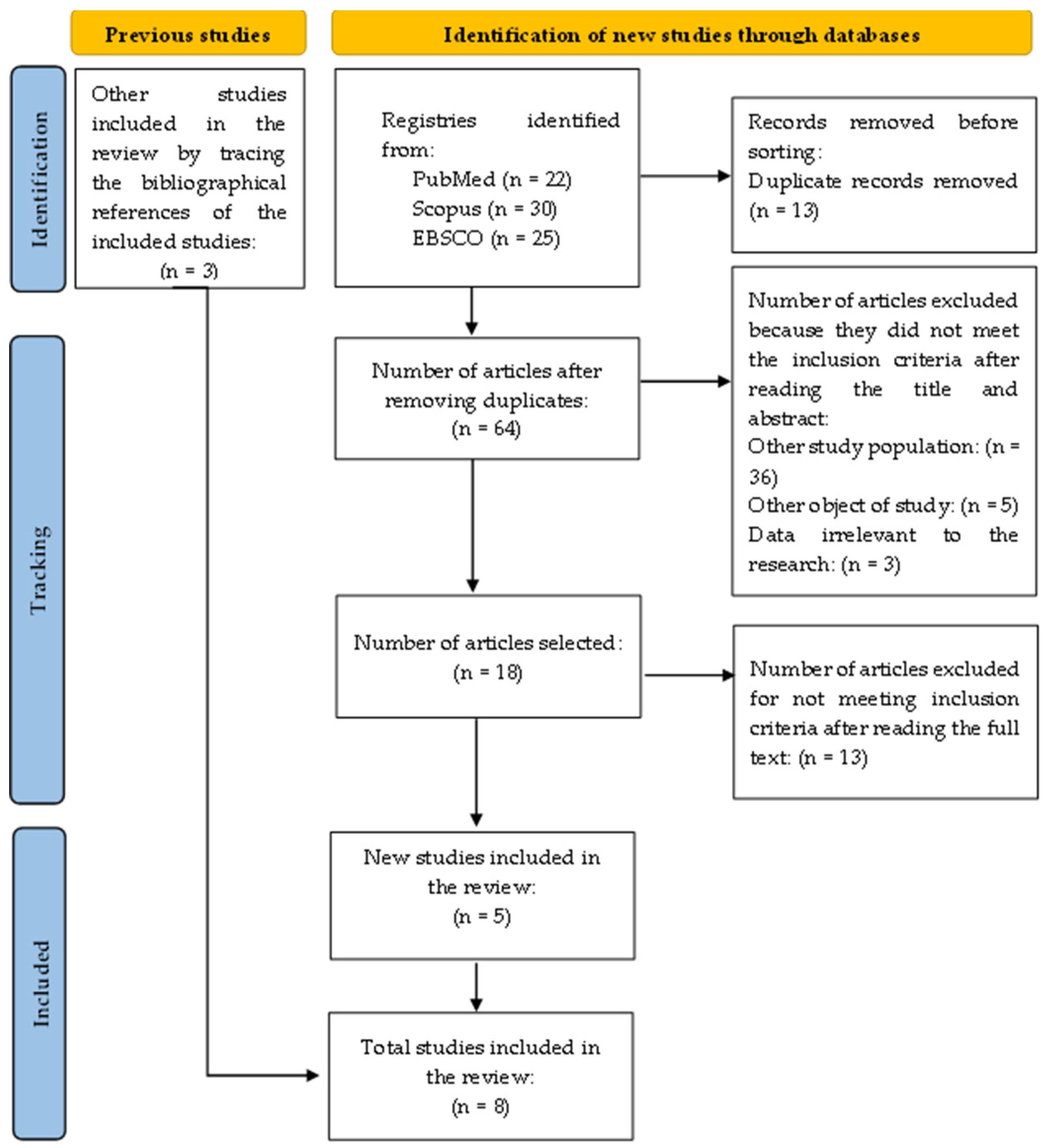

After the search, the reviewers entered all the citations into an Excel® file (considering the low number of studies, total = 75) and removed duplicates. The titles and abstracts were read and selected by two independent reviewers for evaluation according to the inclusion criteria. After this assessment, 18 studies were read in full by two independent reviewers. The two reviewers solved the points where they disagreed through discussion. The search results and the study inclusion process are described in the PRISMA-ScR diagram (Figure 1) [15].

Figure 1.

Presentation of the study selection diagram.

2.4. Data Extraction

Data from the different studies included in this scoping review were extracted by two independent reviewers using a data extraction tool developed by the reviewers. The extracted data will consist of specific details about the participants, concept, context, study method, and main findings relevant to the review questions.

3. Results

We present the main results in table format (Table 2).

Table 2.

Main results of the included studies.

4. Discussion

The current review sought to analyze the evidence for changes in foot biomechanics during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

We found in our research that around half of the body mass acquired during pregnancy is in the woman’s abdominal region (anterior part of the trunk), which leads to changes in the center of gravity and more significant oscillations in the center of pressure [2,21]. These factors induce disturbances in the pregnant woman’s gait [3,12,22]. Changes in foot size may also be due to fluid retention during pregnancy [19,23], a change resulting from this period [24]. In the study by Alcahuz-Griñan [25], a slight increase was reported during the third trimester, which normalizes after delivery, a circumstance also mentioned in other studies cited in the aforementioned study.

In addition, the increases in step width and the kinetic parameters of hip and ankle gait characterize the regular gait pattern in late pregnancy, implying greater use of the hip abductor, hip extensor, and ankle plantar flexor muscle groups. Overuse of these muscle groups during pregnancy can be a contributing factor to lower back pain, foot pain, and painful muscle cramps in gastrocnemius [26].

Starting exercise programs in the early stages of pregnancy will help adjust to changes in static and dynamic grip parameters and balance, especially in the third trimester. Pregnant women need to perform coordination exercises to strengthen the hip, knee, and ankle muscles, which are the supporting muscles. Thus, pregnant women are expected to have less pain in the lower limbs and more outstanding balance [11].

Karadag-Saygi, Unlu-Ozkan, and Basgul [11] suggest that foot pain associated with forefoot loading during pregnancy can be treated with an orthosis to redistribute the increased pressure. Therefore, shoe modification may be necessary for pain relief in pregnant women. In our research, we found another study [6] that suggests that the design of specific footwear or corrective models for pregnancy could be recommended by midwives in response to changes in the feet and the influence of these changes on pain during pregnancy.

The results confirmed that although anthropometric changes are moderate, that pregnant women adopt a more pronated posture [8,16], and that the feet of pregnant women tend to become pronated as pregnancy progresses, not reaching baseline levels even six weeks after giving birth [17]. In this sense, these alterations suggest a change in the gait, causing a decrease in the cadence of the step and in the habitual musculature [16]. Concerning pain, the study by Vico et al. [6] states that although pronation increases during pregnancy, this does not influence the appearance of pain in the lower limbs.

Pregnant women tend to bear more weight on the dominant foot, translating into increased static pressure values in the hindfoot throughout pregnancy [17]. The physiological and biomechanical variabilities of pregnancy impact the distribution of plantar pressures throughout pregnancy, which also depend on individual properties. There was a significant increase in peak pressure only in the hindfoot and midfoot areas in both groups [18]. The effect of orthopedic footwear has not been demonstrated on foot characteristics [18].

The results obtained confirm that the process of the gradual adaptations of the loading pattern on the feet during pregnancy and its dependence on individual anthropometric factors, i.e., the changes in plantar pressure that occur during pregnancy, may be related to both individual biomechanical factors and gait adaptations [3,5]. A longer support time is observed during the load response phase, possibly due to decreased gait speed [20]. Another explanation for the increased support time may be related to the physiological changes of pregnancy itself, which may be a gestational adaptation to better absorb impact due to weight gain [20].

As pregnancy progresses, there is a tendency towards mediolateral oscillation, possibly due to the attempt to increase postural stability by anteriorly shifting the center of gravity due to mass gain [20]. This fact leads to an increase in the support base of up to 30% [13].

Pregnancy seems to be associated with a persistent loss of arch height and rigidity and a more significant arch drop and foot elongation, with greater expression in the first pregnancy [8]. Another study [25] also found a reduction in the height of the foot arch and reported that these changes were more permanent after childbirth. These changes in the feet could contribute to an increased risk of subsequent musculoskeletal disorders in women [8].

Not all the studies included in this review show the time of day when the assessment of the different parameters was carried out, which could be a potential variable skewing the results and even the comparison of the same results in different studies since tiredness accumulates throughout the day and consequently influences the parameters assessed [27,28,29].

Knowing that physical activity and exercise improve endurance, muscle strength, and flexibility, thus improving the musculoskeletal system and posture control [30], assessing the relationship between this variable and changes in the biomechanics of pregnant women’s feet would be essential. This proposal has similarities with the study by Karadag-Saygi et al. [11]. Although the authors did not assess the practice of physical activity, recommendations were made regarding the practice of physical exercise. Also, in another study [31], it is reported that physical activity is important for improving gait stability during pregnancy.

4.1. Limitations

This review did not include other possible languages of publication, only Portuguese and English, so we assume that some evidence may not have been included in this scoping review. However, there was a concern not to set a time limit so as to cover more relevant evidence on the subject.

4.2. Implications for Future Research

Some studies [3,11,17] have found that peak pressure differs between the feet; it has a tendency to be higher in the dominant or right foot. However, none of the studies evaluated the fetal position during the pedobarographic assessment, especially in the third trimester, and the location of placental implantation, which could influence weight distribution and the positioning of the pregnant woman due to discomfort. Therefore, it is essential to understand the relationship between these two variables, the distribution pattern of plantar pressure, and their relationship with physical activity throughout pregnancy and postpartum. In future studies on changes in foot biomechanics during pregnancy and postpartum, data about regular or non-regular physical exercise should also be considered to understand whether this variable has an effect.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, during pregnancy there are changes in the biomechanics of the pregnant woman’s foot which can contribute to the risk of musculoskeletal disorders. These changes are influenced by various factors, including hormonal changes and weight gain. We found that some women experience discomfort and pain in the foot during pregnancy and the postpartum period, which can negatively impact their quality of life and well-being. We found that few longitudinal studies follow changes in foot biomechanics throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period and propose appropriate therapeutic interventions. In this sense, we conclude that more research is needed to determine whether these changes in the foot lead to altered musculoskeletal conditions and/or pain and/or changes in the quality of life of pregnant women.

This scoping review fulfills its purpose, which is to draw attention to the need for more studies on this population and a focus on foot alterations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O.B.Z. and A.F.P.; methodology, M.O.B.Z. and A.F.P.; software, M.O.B.Z. and A.F.P.; validation, M.O.B.Z., A.F.P., M.B. and R.S.-R.; formal analysis, M.O.B.Z. and A.F.P.; research, M.O.B.Z. and A.F.P.; resources, M.O.B.Z. and A.F.P.; data curation, M.O.B.Z. and A.F.P.; preparation of the original draft, M.O.B.Z. and A.F.P.; revision and editing, M.O.B.Z., A.F.P., M.B. and R.S.-R.; visualization, M.O.B.Z., A.F.P., M.B. and R.S.-R.; supervision, M.O.B.Z., A.F.P., M.B. and R.S.-R.; project administration, M.O.B.Z., A.F.P. and R.S.-R.; obtaining funding, M.O.B.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The present publication was funded by Fundação Ciência e Tecnologia, IP national support through CHRC (UIDP/04923/2020).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lowdermilk, D.L.; Perry, S.E.; Cashion, K.; Alden, K.R.; Olshansky, E.F. Maternity and Women’s Health Care, 11th ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-323-16918-9. [Google Scholar]

- Nyska, M.; Sofer, D.; Porat, A.; Howard, C.B.; Levi, A.; Meizner, I. Planter foot pressures in pregnant women. Isr. J. Med. Sci. 1997, 33, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Masłoń, A.; Suder, A.; Curyło, M.; Frączek, B.; Salamaga, M.; Ivanenko, Y.; Forczek-Karkosz, W. Influence of pregnancy related anthropometric changes on plantar pressure distribution during gait-A follow-up study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.P.; Trombini-Souza, F.; de Camargo Neves Sacco, I.; Ruano, R.; Zugaib, M.; João, S.M. Changes in the plantar pressure distribution during gait throughout gestation. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2011, 101, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, Q.; Gu, Y.; Fernandez, J. Alterations of Pregnant Gait during Pregnancy and Postpartum. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vico Pardo, F.J.; López Del Amo, A.; Pardo Rios, M.; Gijon-Nogueron, G.; Yuste, C.C. Changes in foot posture during pregnancy and their relation with musculoskeletal pain: A longitudinal cohort study. Women Birth 2018, 31, e84–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.; Shin, D.; Song, C. Changes in the spinal curvature, degree of pain, balance ability, and gait ability according to pregnancy period in pregnant and nonpregnant women. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, N.A.; Boyer, E.R.; Teran-Yengle, P.; Glass, N.A.; Hillstrom, H.J.; Yack, H.J. Pregnancy leads to lasting changes in foot structure. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 92, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuit, J.; Leyh, C.; Rooze, M.; Feipel, V. Plantar Pressure During Gait in Pregnant Women. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2016, 106, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitternacht, J.; Klement, A.; Lampe, R. Plantar pressure distribution during and after pregnancy. Eur. Orthop. Traumatol. 2013, 4, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag-Saygi, E.; Unlu-Ozkan, F.; Basgul, A. Plantar pressure and foot pain in the last trimester of pregnancy. Foot Ankle Int. 2010, 31, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forczek, W.; Ivanenko, Y.P.; Bielatowicz, J.; Wacławik, K. Gait assessment of the expectant mothers—Systematic review. Gait Posture 2018, 62, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimunová, M.; Kasović, M.; Zvonar, M.; Turčínek, P.; Matković, B.; Ventruba, P.; Vaváček, M.; Knjaz, D. Analysis of ground reaction force in gait during different phases of pregnancy. Kinesiology 2015, 47, 236–241. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, N.A.; Neuman, L.N.; Hochstedler, M.C.; Hillstrom, H.L. Static and dynamic effects of customized insoles on attenuating arch collapse with pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. Foot 2018, 37, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI. 2024. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 1 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Gijon-Nogueron, G.A.; Gavilan-Diaz, M.; Valle-Funes, V.; Jimenez-Cebrian, A.M.; Cervera-Marin, J.A.; Morales-Asencio, J.M. Anthropometric foot changes during pregnancy: A pilot study. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2013, 103, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ramachandra, P.; Kumar, P.; Kamath, A.; Maiya, A.G. Do Structural Changes of the Foot Influence Plantar Pressure Patterns During Various Stages of Pregnancy and Postpartum? Foot Ankle Spec. 2017, 10, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikeska, O.; Gimunová, M.; Zvonař, M. Assessment of distribution of plantar pressures and foot characteristics during walking in pregnant women. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 2019, 21, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wetz, H.H.; Hentschel, J.; Drerup, B.; Kiesel, L.; Osada, N.; Veltmann, U. Changes in shape and size of the foot during pregnancy. Orthopade 2006, 35, 1124–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albino, M.A.; Moccellin, A.S.; Firmento Bda, S.; Driusso, P. Gait force propulsion modifications during pregnancy: Effects of changes in feet’s dimensions. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2011, 33, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, E.E.; Colón, I.; Druzin, M.L.; Rose, J. Postural equilibrium during pregnancy: Decreased stability with an increased reliance on visual cues. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 195, 1104–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, A.R.; Menz, H.B.; Hyde, C.C. The effect of pregnancy on footprint parameters. A prospective investigation. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 1999, 89, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, R.; Stokes, I.A.; Asprinio, D.E.; Trevino, S.; Braun, T. Dimensional changes of the feet in pregnancy. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1988, 70, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widen, E.M.; Gallagher, D. Body composition changes in pregnancy: Measurement, predictors and outcomes. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcahuz-Griñan, M.; Nieto-Gil, P.; Perez-Soriano, P.; Gijon-Nogueron, G. Alterações morfológicas e posturais no pé durante a gravidez e puerpério: Um estudo longitudinal. J. Int. Pesqui. Ambient. E Saúde Pública 2021, 18, 2423. [Google Scholar]

- Foti, T.; Davids, J.R.; Bagley, A. A biomechanical analysis of gait during pregnancy. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2000, 82, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, Á.S.; Bombach, G.D.; Duysens, J.; Carpes, F.P. Differences in foot sensitivity and plantar pressure between young adults and elderly. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 63, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolwijk, N.M.; Duysens, J.; Louwerens, J.W.; Keijsers, N.L. Plantar pressure changes after long-distance walking. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 2264–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, W.K.; Chiu, H.T.; Chao, A.S.; Wang, M.H.; Chen, Y.L. The influence of body mass on foot dimensions during pregnancy. Appl. Ergon. 2015, 46 Pt A, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Rocha, R. Guia da Gravidez Ativa—Atividade Física, Exercício, Desporto e Saúde na Gravidez e Pós-Parto; Escola Superior de Desporto de Rio Maior: Rio Maior, Portugal, 2020; ISBN 978-989-8768-26-1 (print); 978-989-8768-27-4 (e-book). [Google Scholar]

- Forczek, W.; Ivanenko, Y.; Curyło, M.; Frączek, B.; Masłoń, A.; Salamaga, M.; Suder, A. Progressive changes in walking kinematics throughout pregnancy-A follow up study. Gait Posture 2019, 68, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).