COVID-19 Pandemic and Food Insecurity among Pregnant Women in an Important City of the Amazon Region: A Study of the Years 2021 and 2022

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Characterization of the Collection Site

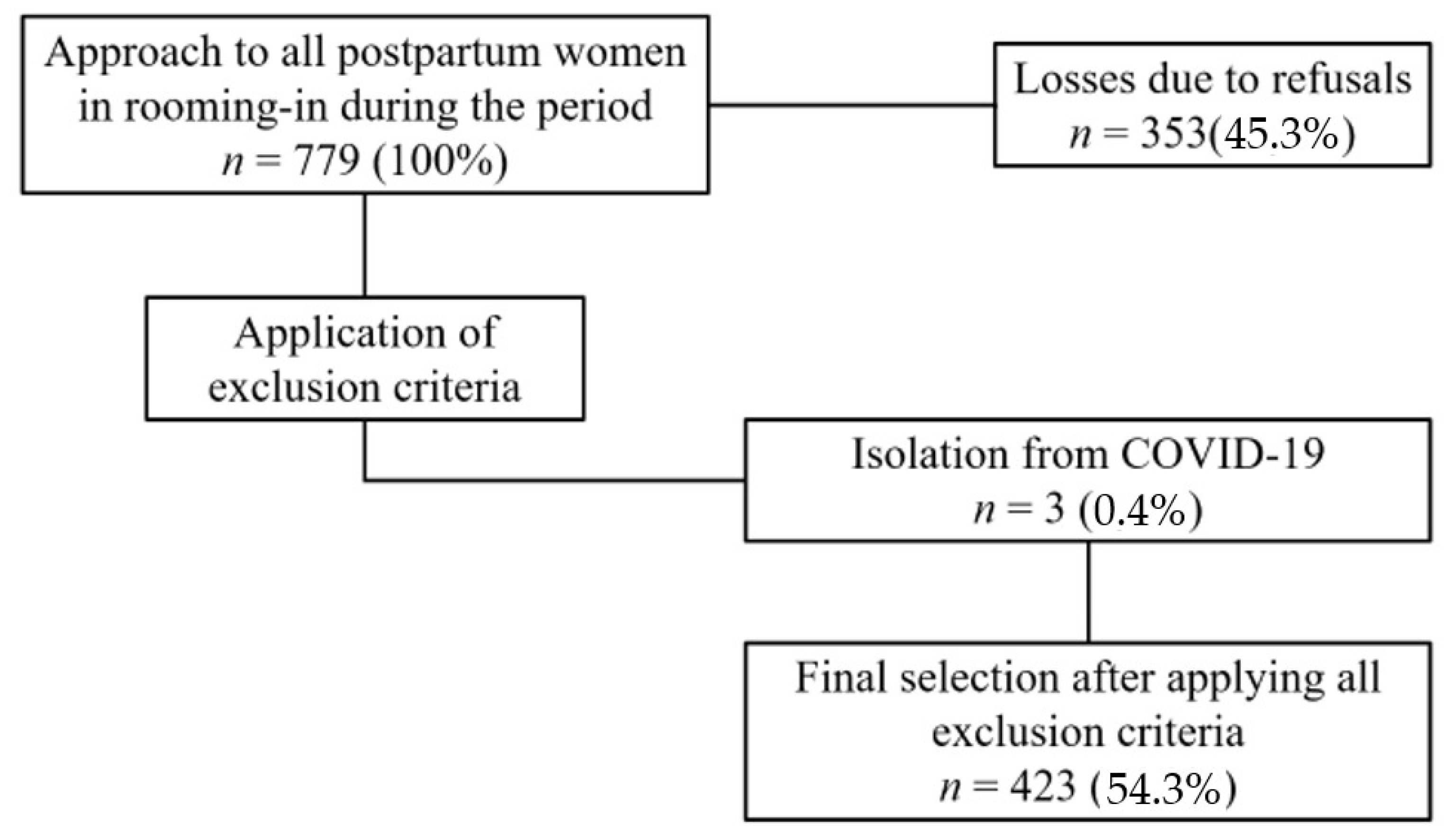

2.3. Population and Selection of the Census Group

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

2.5. Exposure Variables

2.6. Data Analysis

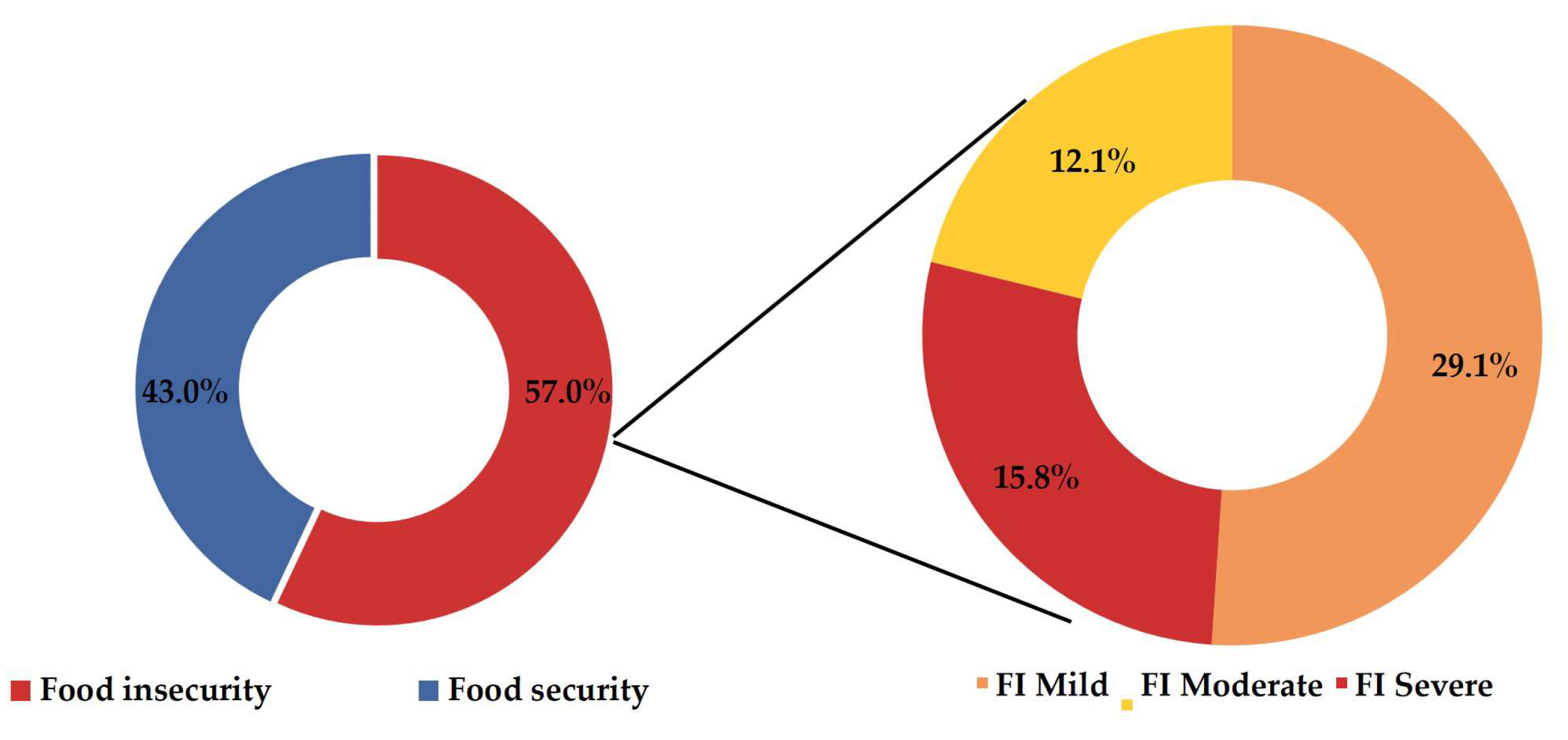

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- BRASIL. Lei no 11.346, de 15 de Setembro de 2006. Cria o Sistema Nacional de Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional–SISAN com Vistas em Assegurar o Direito Humano à Alimentação Adequada e dá Outras Providências. 2006. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2006/lei/l11346.htm (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Bezerra, M.S.; Jacob, M.C.M.; Ferreira, M.A.F.; Vale, D.; Mirabal, I.R.B.; Lyra, C.d.O. Food and nutritional insecurity in Brazil and its correlation with vulnerability markers. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2020, 25, 3831–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. El Estado de la Seguridad Alimentaria y la Nutrición en el Mundo 2018: Fomentando la Resiliencia Climatica en ara de la Seguridad Alimentaria y la Nutricion; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/I9553ES (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. In Transforming Food Systems for Food Security, Improved Nutrition and Affordable Healthy Diets for All; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, J.G.D.; Hoffmann, R.; Miranda, S.H.G.D. Insegurança alimentar, pobreza e distribuição de renda no Brasil. Rev. Econ. E Sociol Rural. 2024, 62, e281936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rede Brasileira de Pesquisa e Soberania e Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional (Rede PENSSAN). Food Insecurity and Covid-19 in Brazil: VIGISAN National Survey of Food Insecurity in the Context of the Covid-19 Pandemic in Brazil. Rede PENSSAN 2021. Available online: http://olheparaafome.com.br/VIGISAN_Inseguranca_alimentar.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Rede Brasileira de Pesquisa e Soberania e Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional (Rede PENSSAN). Food Insecurity and Covid-19 in Brazil: II VIGISAN National Survey on Food Insecurity in the Context of the Covid-19 Pandemic in Brazil. Rede PENSSAN 2022. Available online: https://olheparaafome.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Relatorio-II-VIGISAN-2022.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Barbosa, M.W.; de Sousa, P.R.; de Oliveira, L.K. The Effects of Barriers and Freight Vehicle Restrictions on Logistics Costs: A Comparison before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Brazil. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Silva, R.d.C.; Pereira, M.; Campello, T.; Aragão, É.; Guimarães, J.M.d.M.; Ferreira, A.J.; Barreto, M.L.; dos Santos, S.M.C. Implicações da pandemia COVID-19 para a segurança alimentar e nutricional no Brasil. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2020, 25, 3421–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, L.P.; Schäfer, A.A.; Meller, F.d.O.; Harter, J.; Nunes, B.P.; da Silva, I.C.M.; Pellegrini, D.d.C.P. Tendências e desigualdades na insegurança alimentar durante a pandemia de COVID-19: Resultados de quatro inquéritos epidemiológicos seriados. Cad. De Saude Publica 2021, 37, e00268520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, A.C.M.; Tavares, M.C.M.; Bezerra, A.R. Insegurança alimentar em gestantes da rede pública de saúde de uma capital do nordeste brasileiro. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2017, 22, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto, A.L.P.; Rodrigues, A.V.d.A.; Domingos, T.B.; Salles-Costa, R. Household food insecurity associated with gestacional and neonatal outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, S.M.T.; Hossain, D.; Ahmed, F.; Khan, A.; Begum, F.; Ahmed, T. Association of Household Food Insecurity with Nutritional Status and Mental Health of Pregnant Women in Rural Bangladesh. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmel, B.; Höfelmann, D.A. Mental distress and food insecurity in pregnancy. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2022, 27, 2045–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laraia, B.; Vinikoor-Imler, L.C.; Siega-Riz, A.M. Food insecurity during pregnancy leads to stress, disordered eating, and greater postpartum weight among overweight women. Obesity 2015, 23, 1303–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, F.H.; Spiteri, S.; Zinga, J.; Sulemani, K.; Jacobs, S.E.; Ranjan, N.; Ralph, L.; Raeburn, E.; Threlfall, S.; Bergmeier, M.L.; et al. Systematic Review of Interventions Addressing Food Insecurity in Pregnant Women and New Mothers. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2022, 11, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laraia, B.A.; Siega-Riz, A.M.; Gundersen, C. Household Food Insecurity Is Associated with Self-Reported Pregravid Weight Status, Gestational Weight Gain, and Pregnancy Complications. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastian, A.; Parks, C.; Yaroch, A.; McKay, F.H.; Stern, K.; van der Pligt, P.; McNaughton, S.A.; Lindberg, R. Factors Associated with Food Insecurity among Pregnant Women and Caregivers of Children Aged 0–6 Years: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agho, K.E.; van der Pligt, P. BMC pregnancy and childbirth-‘screening and management of food insecurity in pregnancy’. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalho, A.A.; Holanda, C.M.; Martins, F.A.; Rodrigues, B.T.; Aguiar, D.M.; Andrade, A.M.; Koifman, R.J. Food Insecurity during Pregnancy in a Maternal–Infant Cohort in Brazilian Western Amazon. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, M.U.; Giacomini, I.; Sato, P.M.; Lourenço, B.H.; Nicolete, V.C.; Buss, L.F.; Matijasevich, A.; Castro, M.C.; Cardoso, M.A. SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity and COVID-19 among 5 years-old Amazonian children and their association with poverty and food insecurity. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. In Repurposing Food and Agricultural Policies to Make Healthy Diets More Affordable; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; Available online: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cc0639en (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Schall, B.; Gonçalves, F.R.; Valente, P.A.; Rocha, M.; Chaves, B.S.; Porto, P.; Moreira, A.M.; Pimenta, D.N. Gênero e Insegurança alimentar na pandemia de COVID-19 no Brasil: A fome na voz das mulheres. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva 2022, 27, 4145–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lira, A.F.D.A.; Guilherme, E.; Souza, M.B.D.; Carvalho, L.S. Scorpions (Arachnida, Scorpiones) from the state of Acre, southwestern Brazilian Amazon. Acta Amaz. 2021, 51, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Brasil /Acre / Cruzeiro do Sul. IBGE | Cidades@ | Acre | Cruzeiro do Sul | Panorama. 2023. Available online: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/ac/cruzeiro-do-sul/panorama (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Bernarde, P.S.; Gomes, J.d.O. Venomous snakes and ophidism in Cruzeiro do Sul, Alto Juruá, State of Acre, Brazil. Acta Amaz. 2012, 42, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SINASC-Sistema de Informações sobre Nascidos Vivos. DATASUS Tecnologia da Informação a Serviço do SUS AJUDA. Nascidos Vivos-Acre: Nascim p/ocorrênc por Ano do Nascimento Segundo Município; Município: 120020 CRUZEIRO DO SUL.; Período: 2016–2020. 2024. Available online: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?sinasc/cnv/nvac.def (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- IBGE. Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares, 2017–2018: Análise da Segurança Alimentar no Brasil; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020; 59p. Available online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv101749.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- BRASIL. Cadernos de Atenção Básica: Atenção ao Pré-Natal de Baixo Risco [Internet]; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2012; 318p. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/cadernos_atencao_basica_32_prenatal.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Blencowe, H.; Cousens, S.; Chou, D.; Oestergaard, M.; Say, L.; Moller, A.B.; Kinney, M.; Lawn, J.; Born Too Soon Preterm Birth Action Group. Born Too Soon: The global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health 2013, 10, S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios Contínua: Notas técnicas. Versão 1.7 2020. p. 115. Available online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/index.php/biblioteca-catalogo?view=detalhes&id=2101708 (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Chapanski, V.D.R.; Costa, M.D.; Fraiz, G.M.; Höfelmann, D.A.; Fraiz, F.C. Food insecurity and sociodemographic factors among children in São José dos Pinhais, Paraná, Brazil, 2017: A cross-sectional study. Epidemiol Serv Saude 2021, 30, e2021032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirreff, L.; Zhang, D.; DeSouza, L.; Hollingsworth, J.; Shah, N.; Shah, R.R. Prevalence of Food Insecurity Among Pregnant Women: A Canadian Study in a Large Urban Setting. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2021, 43, 1260–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, F.; Masoumi, S.Z.; Shayan, A.; Shahidi Yasaghi, S.Z. Prevalence of food insecurity in pregnant women and its association with gestational weight gain pattern, neonatal birth weight, and pregnancy complications in Hamadan County, Iran, in 2018. Agric Food Secur. 2020, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr-Porter, M.; Sullivan, A.; Watras, E.; Winn, C.; McNamara, J. Community-Based Designed Pilot Cooking and Texting Intervention on Health-Related Quality of Life among College Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2024, 21, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demétrio, F.; Teles, C.A.d.S.; Santos, D.B.D.; Pereira, M. Food insecurity in pregnant women is associated with social determinants and nutritional outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2020, 25, 2663–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, D.d.C.; Lopes, S.O.; Priore, S.E. Evaluation indicators of Food and Nutritional Insecurity and associated factors: Systematic review. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2020, 25, 2687–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, E.E.S.; Bernardino, Í.d.M.; Pedraza, D.F. Food and nutritional insecurity of families using the Family Health Strategy in the inner Paraíba State. Cad Saúde Coletiva. 2021, 29, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.O.M.; Poblacion, A.; Giudice, C.L.; Moura, L.C.M.D.; Lima, A.A.R.; Lima, D.B.; Toloni, M.H.D.A.; Teixeira, L.G. Factors associated with food insecurity among pregnant women assisted by Universal Health Care in Lavras-Minas Gerais State. Rev. Bras. Saúde Matern. Infant. 2022, 22, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Ali, I. Maternal food insecurity in low-income countries: Revisiting its causes and consequences for maternal and neonatal health. J. Agric. Food Res. 2021, 3, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpino, T.d.M.A.; Santos, C.R.B.; de Barros, D.C.; de Freitas, C.M. COVID-19 and food and nutritional (in)security: Action by the Brazilian Federal Government during the pandemic, with budget cuts and institutional dismantlement. Cad. Saúde Pública 2020, 36, e00161320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciel, B.L.L.; Lyra, C.D.O.; Gomes, J.R.C.; Rolim, P.M.; Gorgulho, B.M.; Nogueira, P.S.; Rodrigues, P.R.M.; Da Silva, T.F.; Martins, F.A.; Dalamaria, T.; et al. Food Insecurity and Associated Factors in Brazilian Undergraduates during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2022, 14, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalho, A.A.; Martins, F.A.; Koifman, R.J. Food insecurity during the gestational period and factors associated with maternal and child health. J. Nutr. Health Food Eng. 2017, 7, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fernandes, R.C.; Manera, F.; Boing, L.; Höfelmann, D.A. Socioeconomic, demographic, and obstetric inequalities in food insecurity in pregnant women. Rev. Bras. Saúde Matern. Infant. 2018, 18, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domene, S.; Álvares, M.; Agostini, K.; Almeida, G.N.P.D.; Camargo, R.G.M.; Carvalho, A.; Corrêa, F.E.; Delbem, A.C.B.; Domingos, S.S.; Drucker, D.P.; et al. Segurança alimentar: Reflexões sobre um problema complexo. Estud. Av. 2023, 23, 181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables/Categories | n = 423 | % = 100 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± Standard Deviation | Min. | Max. | |

| Age (Years) | 24.87 ± 6.69 | 13 | 44 |

| Number of residents | 4.71 ± 1.96 | 2 | 14 |

| Number of pregnancies | 2.51 ± 2.09 | 1 | 19 |

| Birth weight (Kg) | 3.390 ± 0.509 | 1.070 | 4.680 |

| n | % | ||

| Education | |||

| No education | 7 | 1.7 | |

| Incomplete/Complete elementary education | 124 | 29.3 | |

| Incomplete/Complete high school education | 223 | 52.7 | |

| Higher education/Postgraduate degree | 69 | 16.4 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single/Divorced/Separated | 97 | 22.9 | |

| Married/Common-law marriage | 326 | 77.1 | |

| Self-reported race | |||

| White | 34 | 8.0 | |

| Black | 50 | 11.8 | |

| Brown/Mixed race | 326 | 77.1 | |

| Yellow | 6 | 1.4 | |

| Indigenous | 7 | 1.7 | |

| Head of household | |||

| Partner | 206 | 48.7 | |

| Woman | 61 | 14.4 | |

| Both (partner/woman) | 75 | 17.7 | |

| Others | 81 | 19.1 | |

| Occupation | |||

| With remuneration | 116 | 27.4 | |

| Without remuneration | 307 | 72.6 | |

| Social Class a | |||

| Class A (+15 salaries) | 4 | 0.9 | |

| Class B (5 to 15 salaries) | 5 | 1.2 | |

| Class C (3 to 5 salaries) | 24 | 5.7 | |

| Class D (1 to 3 salaries) | 111 | 26.2 | |

| Class E (up to 1 salary) | 279 | 66.0 | |

| Receipt of government assistance | |||

| No | 209 | 49.4 | |

| Yes | 214 | 50.6 | |

| Housing Situation | |||

| Own | 335 | 79.2 | |

| Rented | 35 | 8.3 | |

| Provided | 53 | 12.5 | |

| Residential Zone | |||

| Urban | 161 | 38.1 | |

| Rural | 262 | 61.9 | |

| Water Source | |||

| Piped | 203 | 48.0 | |

| Well | 82 | 19.4 | |

| Cistern | 95 | 22.4 | |

| Rivers or streams | 43 | 10.2 | |

| Electricity | |||

| No | 49 | 11.6 | |

| Yes | 374 | 88.4 | |

| Type of Sewage | |||

| None | 43 | 10.2 | |

| Public sewer system | 79 | 18.7 | |

| Septic tank | 144 | 34.0 | |

| Primitive septic tank | 52 | 12.3 | |

| Open ditch/river or stream | 105 | 24.8 | |

| Residents under 18 years old | |||

| No | 93 | 22.0 | |

| Yes | 330 | 78.0 | |

| Variables/Categories | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 423 | 100 | |

| Clinical and prenatal characteristics | ||

| Type of prenatal care | ||

| Mixed | 37 | 8.7 |

| Private | 17 | 4.0 |

| Public | 369 | 87.2 |

| Primiparity | ||

| No | 248 | 58.6 |

| Yes | 175 | 41.4 |

| Childbirth method | ||

| Cesarean section | 285 | 67.4 |

| Vaginal | 138 | 32.6 |

| Nutritional status in the last trimester of pregnancy (n = 421) a | ||

| Adequate | 166 | 39.2 |

| Low weight | 60 | 14.2 |

| Overweight and Obesity | 195 | 46.1 |

| Gestational diabetes | ||

| No | 287 | 67.8 |

| Yes | 71 | 16.8 |

| Unknown | 65 | 15.4 |

| Increased blood pressure levels during pregnancy | ||

| No | 352 | 83.2 |

| Yes | 71 | 16.8 |

| Diagnosis of COVID-19 during pregnancy | ||

| No | 385 | 91.0 |

| Yes | 38 | 9.0 |

| Newborn characteristics | ||

| Prematurity | ||

| No | 391 | 92.4 |

| Yes | 32 | 7.6 |

| Low birth weight | ||

| No | 397 | 93.9 |

| Yes | 26 | 6.1 |

| Macrosomia | ||

| No | 395 | 93.4 |

| Yes | 28 | 6.6 |

| Hospitalization in the ICU b | ||

| No | 410 | 96.9 |

| Yes | 13 | 3.1 |

| Variables/Categories | Food Insecurity (n = 423) | Crude Analysis | Adjusted Analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No n (%) | Yes n (%) | |||||||||

| 182 (43) | 241 (57) | PR a | CI 95% b | p-Value c | PR a | CI 95% b | p-Value c | |||

| Age | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| ≥20 | 145 | 50.5 | 142 | 49.5 | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | ||

| <20 | 37 | 27.2 | 99 | 72.8 | 1.47 | 1.37–1.72 | 1.52 | 1.29–1.79 | ||

| Years of Education | 0.001 | |||||||||

| >9 years | 140 | 47.9 | 152 | 52.1 | 1.00 | - | ||||

| ≤9 years | 42 | 32.1 | 89 | 67.9 | 1.30 | 1.11–1.53 | ||||

| Marital Status | 0.160 | |||||||||

| With partner | 36 | 37.1 | 61 | 62.9 | 1.00 | |||||

| Without partner | 146 | 44.8 | 180 | 55.2 | 0.88 | 0.73–1.05 | ||||

| Self-reported Race | 0.895 | |||||||||

| White | 15 | 44.1 | 19 | 55.9 | 1.00 | - | ||||

| Non-white | 167 | 42.9 | 222 | 57.1 | 1.02 | 0.75–1.39 | ||||

| Occupation | 0.023 | |||||||||

| With remuneration | 61 | 52.6 | 55 | 47.4 | 1.00 | |||||

| Without remuneration | 121 | 39.4 | 186 | 60.6 | 1.28 | 1.03–1.58 | ||||

| Social Class d | 0.012 | |||||||||

| Class A, B, and C (more than 3 salaries) | 23 | 69.7 | 10 | 30.3 | 1.00 | |||||

| Class D and E (up to 3 salaries) | 159 | 40.8 | 231 | 59.2 | 1.96 | 1.16– 3.30 | ||||

| Receipt of government assistance | 0.019 | 0.002 | ||||||||

| No | 102 | 48.8 | 107 | 51.2 | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | ||

| Yes | 80 | 37.4 | 134 | 62.6 | 1.22 | 1.03–1.45 | 1.31 | 1.10–1.55 | ||

| Family job loss during pandemic | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 159 | 47.7 | 174 | 52.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | - | |||

| Yes | 23 | 25.6 | 67 | 74.4 | 1.42 | 1.22–1.67 | 1.40 | 1.20–1.64 | ||

| Own domicile | 0.040 | |||||||||

| No | 30 | 34.1 | 58 | 65.9 | 1.00 | - | ||||

| Yes | 152 | 45.4 | 183 | 54.6 | 0.83 | 0.69–0.99 | ||||

| Number of residents | 0.014 | 0.047 | ||||||||

| ≤4 residents | 117 | 48.1 | 125 | 51.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | - | |||

| >4 residents | 66 | 36.3 | 116 | 63.7 | 1.23 | 1.04–1.45 | 1.17 | 1.00–1.37 | ||

| Residential Zone | 0.023 | |||||||||

| Urban | 81 | 50.3 | 80 | 49.7 | 1.00 | - | ||||

| Rural | 101 | 38.5 | 161 | 61.5 | 1.24 | 1.03–1.48 | ||||

| Piped Water | 0.473 | |||||||||

| No | 91 | 41.4 | 129 | 58.6 | 1.00 | - | ||||

| Yes | 91 | 44.8 | 112 | 55.2 | 0.94 | 0.80–1.11 | ||||

| Electricity | 0.003 | |||||||||

| No | 13 | 26.5 | 36 | 73.5 | 1.00 | - | ||||

| Yes | 169 | 45.2 | 205 | 54.8 | 0.75 | 0.62–0.90 | ||||

| Type of sewage in the residence | 0.007 | 0.064 | ||||||||

| Public sewerage system; Septic tank or rudimentary | 131 | 47.6 | 143 | 52.4 | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | ||

| None; Open-air ditch; River or stream | 51 | 34.5 | 97 | 65.5 | 1.25 | 1.06–1.47 | 1.16 | 0.99–1.36 | ||

| Type of prenatal care | 0.001 | 0.032 | ||||||||

| Private or mixed | 37 | 68.5 | 17 | 31.5 | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | ||

| Public | 145 | 39.3 | 224 | 60.7 | 1.93 | 1.29–2.88 | 1.53 | 1.04–2.26 | ||

| Number of ANC e | 0.009 | |||||||||

| ≥6 ANC | 152 | 46.1 | 178 | 53.9 | 1.00 | - | ||||

| <6 ANC | 30 | 32.3 | 63 | 67.7 | 1.26 | 1.06–1.49 | ||||

| Childbirth method | 0.007 | |||||||||

| Cesarean section | 135 | 47.4 | 150 | 52.6 | 1.00 | - | ||||

| Vaginal | 47 | 34.1 | 91 | 65.9 | 1.25 | 1.06–1.47 | ||||

| Prematurity of the newborn | 0.168 | |||||||||

| No | 164 | 41.9 | 227 | 58.1 | 1.00 | - | ||||

| Yes | 18 | 56.3 | 14 | 43.8 | 0.75 | 0.50–1.13 | ||||

| Low birth weight | 0.528 | |||||||||

| No | 171 | 42.6 | 230 | 57.4 | 1.00 | - | ||||

| Yes | 11 | 50.0 | 11 | 50.0 | 0.87 | 0.57–1.34 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, M.T.L.d.; Costa, K.M.d.M.; Ramalho, A.A.; Valentim-Silva, J.R.; Andrade, A.M.d. COVID-19 Pandemic and Food Insecurity among Pregnant Women in an Important City of the Amazon Region: A Study of the Years 2021 and 2022. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 710. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21060710

Santos MTLd, Costa KMdM, Ramalho AA, Valentim-Silva JR, Andrade AMd. COVID-19 Pandemic and Food Insecurity among Pregnant Women in an Important City of the Amazon Region: A Study of the Years 2021 and 2022. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(6):710. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21060710

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Maria Tamires Lucas dos, Kleynianne Medeiros de Mendonça Costa, Alanderson Alves Ramalho, João Rafael Valentim-Silva, and Andreia Moreira de Andrade. 2024. "COVID-19 Pandemic and Food Insecurity among Pregnant Women in an Important City of the Amazon Region: A Study of the Years 2021 and 2022" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 6: 710. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21060710

APA StyleSantos, M. T. L. d., Costa, K. M. d. M., Ramalho, A. A., Valentim-Silva, J. R., & Andrade, A. M. d. (2024). COVID-19 Pandemic and Food Insecurity among Pregnant Women in an Important City of the Amazon Region: A Study of the Years 2021 and 2022. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(6), 710. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21060710