Impact of Long Working Hours on Mental Health Status in Japan: Evidence from a National Representative Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

3. Empirical Study Methodology

3.1. Model

3.2. Date and Variable Setting

- (a)

- Do you feel nervous?

- (b)

- Do you feel hopeless?

- (c)

- Do you feel restless?

- (d)

- Do you feel depressed and like nothing could clear your mind?

- (e)

- Did you experience difficulty in doing anything?

- (f)

- Do you feel worthlessness?

- (a)

- 40 h (1 = 40 h, 0 = otherwise)

- (b)

- 45 h (1 = 45 h, 0 = otherwise)

- (c)

- 50 h (1 = 50 h, 0 = otherwise)

- (d)

- 55 h (1 = 55 h, 0 = otherwise)

- (e)

- 60 h (1 = 60 h, 0 = otherwise)

- (1)

- A female dummy variable (1= female, 0 = male) was used to control for the gender gap in work hours, as numerous studies have reported that work hours differ by gender, with men generally working longer hours than women.

- (2)

- To account for potential differences in work hours among age groups (younger, middle-aged, and older), we included age as a variable in our analysis.

- (3)

- The co-residence relationship dummy variable was used to control for the influence of family members on mental health status.

- (4)

- Occupational dummy variables were employed in the analysis to categorize workers into nine types of occupations: (a) manager; (b) professional job; (c) clerks; (d) sales job; (e) service job; (f) security job; (g) agriculture, forestry, and fishery job; (h) elementary job; and (i) other occupations.

- (5)

- To account for the influence of firm size on mental health status, we included eight types of firm size dummy variables: (a) 1–29 employees, (c) 30–99 employees, (d) 100–299 employees, (e) 300–499 employees, (f) 500–999 employees, (g) 1000–4999 employees, (h) 5000 or more employees, and (i) government offices.

- (6)

- We consider the impact of non-earned income on labor supply and household income.

- (7)

- The spouse’s employment status was categorized using seven types of dummy variables: (a) regular worker, (b) part-time worker, (c) temporary worker, (d) dispatched worker, (e) contract worker, (f) entrusted worker, and (g) other employment status excepting the above types.

- (8)

- To control the influence of childcare on working hours, we constructed a variable representing the number of children.

- (9)

- We created five types of dummy variables representing regions based on the population in cities to control for the influence of city size on mental health status: (a) city with a population of less than 50 thousand; (b) city with a population of 50–149 thousand; (c) city with a population of 150 thousand; (d) large city; and (e) countryside.

4. Descriptive Statistics Results

5. Econometric Analysis Results

5.1. Results Based on the OLS Method

- (1)

- Model 1: Using the working hours variable and excluding the interaction term.

- (2)

- Model 2: Using the 40-h dummy variable and including the interaction term.

- (3)

- Model 3: Using the 50-h dummy variable and including the interaction term.

- (4)

- Model 4: Using the 55-h dummy variable and including the interaction term.

- (5)

- Model 5: Using the 60-h dummy variable and including the interaction term.

5.2. Results Based on the PSM Method

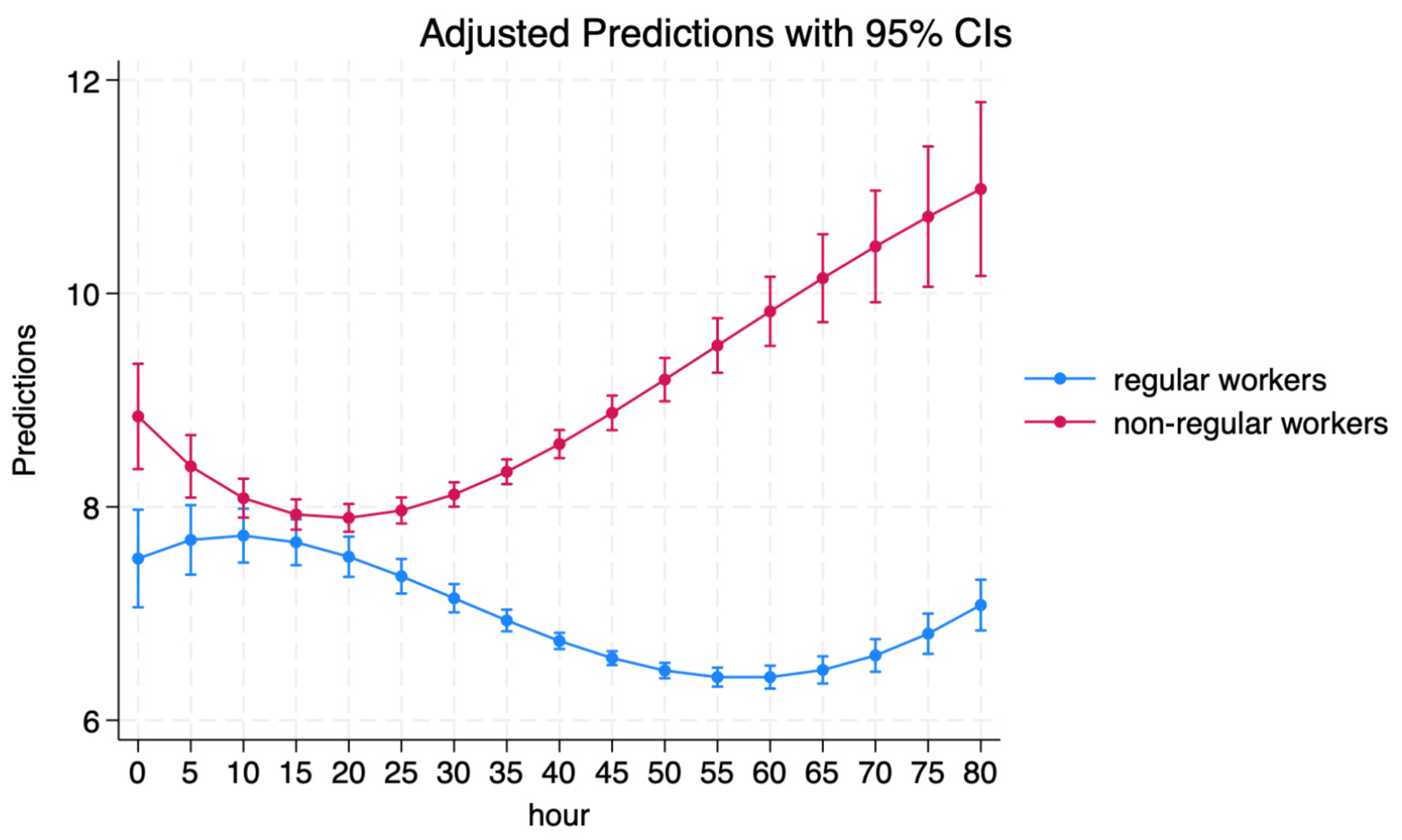

5.3. Results by Regular and Non-Regular Workers Based on the PSM Method

5.4. Results by Gender and Work-Related Groups Based on the PSM Method

6. Discussion

6.1. Novel Findings of This Study

6.2. Practical Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Total | Male | Female | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dF/dx | dF/dx | dF/dx | ||||

| Age group [Ref.: Age 30–39] | ||||||

| Age 15–29 | 0.060 | *** | 0.081 | *** | −0.015 | * |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.009) | ||||

| Age 40–49 | 0.030 | *** | −0.013 | *** | 0.033 | *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.007) | ||||

| Age 50+ | 0.189 | *** | 0.243 | *** | 0.073 | *** |

| (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.007) | ||||

| Ln family income | −0.116 | *** | −0.084 | *** | −0.115 | *** |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.004) | ||||

| Marital status [Married] | ||||||

| Unmarried | −0.015 | *** | 0.089 | *** | −0.189 | *** |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.009) | ||||

| Widow/Widower | 0.092 | *** | 0.014 | −0.022 | ||

| (0.012) | (0.016) | (0.015) | ||||

| Divorced | −0.015 | ** | −0.009 | −0.168 | *** | |

| (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.010) | ||||

| Education [Ref.: Senior high school] | ||||||

| Junior high school | 0.060 | *** | 0.072 | *** | 0.053 | *** |

| (0.007) | (0.008) | (0.013) | ||||

| Training college | −0.007 | −0.007 | −0.023 | *** | ||

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.007) | ||||

| Junior college/technical college | 0.094 | *** | −0.008 | 0.023 | *** | |

| (0.006) | (0.010) | (0.007) | ||||

| University | −0.070 | *** | −0.002 | −0.045 | *** | |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.007) | ||||

| Graduate school | −0.093 | *** | −0.005 | −0.065 | ** | |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.025) | ||||

| Occupation [Ref.: Manager] | ||||||

| Technician | 0.138 | *** | 0.055 | *** | 0.215 | *** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.020) | ||||

| Clerk | 0.234 | *** | 0.081 | *** | 0.277 | *** |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.020) | ||||

| Sales workers | 0.353 | *** | 0.118 | *** | 0.542 | *** |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.021) | ||||

| Service workers | 0.458 | *** | 0.251 | *** | 0.556 | *** |

| (0.007) | (0.008) | (0.020) | ||||

| Security workers | 0.168 | *** | 0.151 | *** | 0.072 | |

| (0.014) | (0.013) | (0.050) | ||||

| Agriculture, forestry and fishery workers | 0.271 | *** | 0.156 | *** | 0.506 | *** |

| (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.036) | ||||

| Elementary occupations | 0.214 | *** | 0.099 | *** | 0.482 | *** |

| (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.021) | ||||

| Not elsewhere classified | 0.438 | *** | 0.272 | *** | 0.565 | *** |

| (0.011) | (0.013) | (0.023) | ||||

| Firm Size [Ref: 1–4 workers] | ||||||

| 5–29 | −0.011 | −0.015 | −0.007 | |||

| (0.008) | (0.010) | (0.012) | ||||

| 30–99 | −0.023 | *** | 0.002 | −0.046 | *** | |

| (0.009) | (0.010) | (0.012) | ||||

| 100–299 | −0.035 | *** | 0.002 | −0.062 | *** | |

| (0.009) | (0.010) | (0.012) | ||||

| 200–499 | −0.050 | *** | −0.010 | −0.068 | *** | |

| (0.010) | (0.011) | (0.014) | ||||

| 500–999 | −0.027 | *** | 0.008 | −0.034 | ** | |

| (0.010) | (0.011) | (0.014) | ||||

| 1000–4999 | −0.031 | *** | −0.009 | −0.013 | ||

| (0.009) | (0.011) | (0.013) | ||||

| 5000+ | −0.051 | *** | −0.018 | * | −0.033 | ** |

| (0.009) | (0.011) | (0.014) | ||||

| Government office | −0.072 | *** | −0.050 | *** | −0.049 | *** |

| (0.010) | (0.011) | (0.014) | ||||

| Spouse’s employment status [Ref.: Non-work] | ||||||

| Regular worker | 0.146 | *** | −0.062 | *** | 0.042 | *** |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.007) | ||||

| Part-time | −0.138 | *** | −0.041 | *** | 0.026 | |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.022) | ||||

| Temporary worker | −0.005 | 0.024 | * | 0.041 | ||

| (0.013) | (0.015) | (0.028) | ||||

| Dispatched worker | −0.024 | −0.029 | 0.051 | |||

| (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.045) | ||||

| Contract worker | 0.081 | *** | 0.018 | 0.092 | *** | |

| (0.012) | (0.014) | (0.018) | ||||

| Entrusted worker | 0.127 | *** | 0.040 | * | 0.113 | *** |

| (0.017) | (0.023) | (0.025) | ||||

| Other | 0.046 | −0.015 | 0.049 | |||

| (0.029) | (0.032) | (0.047) | ||||

| Number of children | 0.194 | *** | 0.111 | *** | 0.246 | *** |

| (0.012) | (0.011) | (0.019) | ||||

| City Scale [Ref.: Large city (Population 150 thousands)] | ||||||

| Population 50–149 | −0.027 | *** | −0.015 | *** | −0.039 | *** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.007) | ||||

| Population 50 or less | −0.031 | *** | −0.017 | *** | −0.050 | *** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.007) | ||||

| County | −0.051 | *** | −0.026 | *** | −0.083 | *** |

| (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.009) | ||||

| Constant term | −0.052 | *** | −0.032 | *** | −0.082 | *** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.009) | ||||

| Number of Observations | 75,602 | 40,396 | 35,206 | |||

| Pseudo-R-squares | 0.153 | 0.199 | 0.182 | |||

| Log Likelihood | −41,931.3 | −15,866.9 | −19,772.6 | |||

| Chi2 | 12,785 | 6598.7 | 7160.1 | |||

References

- Lee, S.; McCann, D.; Messenger, J.C. Working Time around the World: Trend in Working Hours, Laws and Policies in a Global Comparative Perspective; International Labor Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dattani, S.; Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. OurWorldInData.org. Mental Health. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Available online: https://www.who.int/china/health-topics/mental-health (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Sparks, K.; Cooper, C.; Fried, Y.; Shirom, A. The Effect of Hours of Work on Health: A Meta-analytic Review. J. Occup. Psychol. 1997, 70, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannai, A.; Tamakoshi, A. The Association between Long Working Hours and Health: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Evidence. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2014, 40, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopasker, D.; Montagna, C.; Bender, K.A. Economic Insecurity: A Socioeconomic Determinant of Mental Health. SSM Popul. Health 2018, 6, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mclsaac, M.A.; Reaume, M.; Phillips, S.P.; Michaelson, V.; Steeves, V.; Davison, C.M.; Vafae, A.; King, N.; Pickett, W. A Novel Application of a Data Mining Technique to Study Intersections in the Social Determinants of Mental Health among Young Canadians. SSM Popul. Health 2021, 16, 100946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verduin, F.; Smid, G.E.; Wind, T.R.; Scholte, W.F. In Search of Links between Social Capital, Mental Health and Sociotherapy: A Longitudinal Study in Rwanda. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 121, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Piao, X.; Oshio, T. Impact of Social Participation on Health among Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults: Evidence from Longitudinal Survey Data in China. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Symoens, S.; Colman, E.; Bracke, P. Divorce, Conflict, and Mental Health: How the Quality of Intimate Relationships is Linked to Post-Divorce Well-being. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 44, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jace, C.E.; Makridis, C.A. Does Marriage Protect Mental Health? Evidence from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Soc. Sci. Q. 2021, 102, 2499–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Yang, F. Motherhood Health Penalty: Impact of Fertility on Physical and Mental Health of Chinese Women of Childbearing Age. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 787844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.M.; Cho, S. Socioeconomic Status, Work-Life Conflict, and Mental Health. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2022, 63, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, R.N.; Alp, Y.T.; Shell, I.A. The Mental Health Consequences of Work-Life and Life-Work Conflicts for STEM Postdoctoral Trainees. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 750490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, V.; Smyth, R. Work Hours in Chinese Enterprises: Evidence from Matched Employer-Employee Data. Ind. Relat. 2013, 44, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, P.; Fonseca, M.; Pires, J.F. Impact of Working Hours on Sleep and Mental Health. Occup. Med. 2017, 67, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.; Chan, A.H.S.; Ngan, S.C. The Effect of Long Working Hours and Overtime on Occupational Health: A Meta-Analysis of Evidence from 1998 to 2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Kuroda, S.; Owan, H. Mental Health Effect of Long Work Hours, Night and Weekend Work, and Short Rest Periods. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 246, 11274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujino, Y.; Horie, S.; Hoshuyama, T.; Tsutsui, T.; Tanaka, Y. A Systematic Review of Working Hours and Mental Health Burden. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi 2006, 48, 87–97. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, R.; Seo, E.; Takami, M.; Ito, M.; Sanuki, M.; Maeno, T. The Relationship between Long Working Hours and Depression among First-year Residents in Japan. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hino, A.; Inoue, A.; Mafune, K.; Hiro, H. The Effect of Changes in Overtime Work Hours on Depressive Symptoms among Japanese White-Collar Workers: A 2-year Follow-up Study. J. Occup. Health 2018, 61, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuno, K.; Kawachi, I.; Inoue, A.; Nakai, S.; Tanigaki, T.; Nagatomi, H.; Kawakami, N. JSTRESS Group Long Working Hours and Depressive Symptoms: Moderating Effects of Gender, Socioeconomic Status, and Job Resources. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2019, 92, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, H.; Odagiri, Y.; Ohya, Y.; Nakanishi, Y.; Shimomitsu, T.; Theorell, T.; Inoue, S. Association of Overtime Work Hours with Various Stress Responses in 59,021 Japanese Workers: Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochiai, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Matsuo, T.; Sasaki, T.; Sato, Y.; Fukasawa, K.; Araki, T.; Otsuka, Y. Characteristics of Long Working Hours and Subsequent Psychological and Physical Responses: JNIOSH Cohort Study. Occup. Environ. Med. 2022, 80, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X. Do Long Work Hours Cause Mental Health Problems of Workers? In Dynamism of Household Behavior in Japan V: Rising Quality of the Labor Market and Employment Behavior; Higuchi, Y., Seko, M., Teruyama, H., Eds.; Keio University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2009. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda, S.; Yamamoto, I. Why Do People Overwork at the Risk of Impairing Mental Health? J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 1519–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, S. Hours of Work and Health in Japan. Ann. Epidemiol. 2019, 33, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X. A Comparison of the Wage Differentials in Regular and Irregular Sectors between Japan and China. J. Ohara Inst. Soc. Res. 2009, 601, 17–28. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Nagase, N. The Gap between Non-Regular and Regular Employment. Jpn. Inst. Labour Policy Train. 2018, 691, 19–38. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi, D. Empirical Analysis of Wage Differentials between Employment Types. Jpn. Inst. Labour Policy Train. 2018, 701, 4–16. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Guston, N.; Kishi, T. Part-time Workers Doing Full-Time Work in Japan. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 2007, 21, 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A. Job Demands, Job Decision Latitude, and Mental Strain. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse Health Effects of High-Effect/Low-Reward and Conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gronau, R. Leisure, Home Production, and Work: The Theory of the Allocation of Time Revisited. J. Pol. Econ. 1977, 85, 1099–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S. Human Capital, Effort, and the Sexual Division of Labor. J. Labor Econ. 1985, 3, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.J.; Erickson, J.J.; Holmes, E.K.; Ferris, M. Workplace Flexibility, Work Hours, and Work-Life Conflict: Finding an Extra Day or Two. J. Fam. Psychol. 2010, 24, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henly, J.R.; Lambert, S.J. Unpredictable Work Timing in Retail Jobs: Implications for Employee Work–Life Conflict. ILR Rev. 2014, 67, 986–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoikov, V. Size of Firm, Worker Earnings, and Human Capital: The case of Japan. ILR Rev. 1973, 26, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, K. How Does Firm Size Determine the Wage Distribution of Wage and Quality of Job? From the Perspective of Dual Labor Market Hypothesis. Jpn. Sociol. Rev. 2022, 73, 230–245. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Weekly Working Hours ≥ 55 h (N = 5931) | Weekly Working Hours < 55 h (N = 52,446) | Gap | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (a) | S.D. | Mean (b) | S.D. | a–b | |

| Mental health score | 3.536 | 4.387 | 3.204 | 4.086 | 0.332 |

| Weekly work hours | 64.375 | 7.066 | 36.264 | 12.785 | 28.111 |

| Female dummy | 0.121 | 0.327 | 0.489 | 0.500 | 0.368 |

| Log of age | 3.772 | 0.239 | 3.863 | 0.260 | −0.091 |

| Having a spouse | 0.083 | 0.276 | 0.380 | 0.485 | 0.297 |

| Number of children | 0.018 | 0.136 | 0.017 | 0.136 | 0.001 |

| Log of family income | 6.432 | 0.568 | 6.325 | 0.662 | 0.107 |

| Family Income | 721.765 | 418.416 | 673.128 | 403.529 | 48.637 |

| Employment status | |||||

| Non-regular worker | 0.070 | 0.255 | 0.414 | 0.493 | −0.344 |

| Regular worker | 0.930 | 0.255 | 0.586 | 0.493 | 0.344 |

| Occupation | |||||

| Managers | 0.114 | 0.318 | 0.065 | 0.247 | 0.049 |

| Professional | 0.312 | 0.463 | 0.259 | 0.438 | 0.053 |

| Clerk | 0.067 | 0.251 | 0.172 | 0.377 | −0.105 |

| Sale job | 0.102 | 0.302 | 0.076 | 0.265 | 0.026 |

| Service job | 0.113 | 0.317 | 0.167 | 0.373 | −0.054 |

| Security job | 0.030 | 0.170 | 0.016 | 0.125 | 0.014 |

| Agriculture, forestry, and fishery job | 0.010 | 0.100 | 0.010 | 0.097 | 0.000 |

| Elementary job | 0.229 | 0.420 | 0.198 | 0.399 | 0.031 |

| Not elsewhere classified | 0.022 | 0.148 | 0.037 | 0.188 | −0.015 |

| Firm size | |||||

| 1–4 | 0.029 | 0.168 | 0.046 | 0.209 | −0.017 |

| 5–29 | 0.185 | 0.388 | 0.203 | 0.402 | −0.018 |

| 30–99 | 0.176 | 0.380 | 0.173 | 0.378 | 0.003 |

| 100–299 | 0.144 | 0.351 | 0.147 | 0.354 | −0.003 |

| 200–499 | 0.063 | 0.244 | 0.063 | 0.242 | 0.000 |

| 500–999 | 0.062 | 0.242 | 0.069 | 0.253 | −0.007 |

| 1000–4999 | 0.107 | 0.309 | 0.104 | 0.306 | 0.003 |

| 5000– | 0.103 | 0.304 | 0.105 | 0.307 | −0.002 |

| Government office | 0.131 | 0.337 | 0.091 | 0.288 | 0.040 |

| Spouse’s type of employment status | |||||

| Not in work | 0.494 | 0.500 | 0.458 | 0.498 | 0.036 |

| Regular worker | 0.213 | 0.410 | 0.342 | 0.474 | −0.129 |

| Part-time worker | 0.224 | 0.417 | 0.133 | 0.339 | 0.091 |

| Temporary worker | 0.021 | 0.144 | 0.017 | 0.130 | 0.004 |

| Dispatched worker | 0.010 | 0.101 | 0.006 | 0.080 | 0.004 |

| Contract worker | 0.024 | 0.154 | 0.027 | 0.162 | −0.003 |

| Entrusted worker | 0.009 | 0.095 | 0.012 | 0.110 | −0.003 |

| Other | 0.004 | 0.062 | 0.004 | 0.066 | 0.000 |

| Scale of resident city (thousands) | |||||

| Large city (more than 150) | 0.262 | 0.440 | 0.228 | 0.419 | 0.034 |

| Population Scale 150 | 0.311 | 0.463 | 0.298 | 0.457 | 0.013 |

| Population Scale 50–149 | 0.255 | 0.436 | 0.272 | 0.445 | −0.017 |

| Population Scale 149 or less | 0.066 | 0.249 | 0.085 | 0.279 | −0.019 |

| County | 0.106 | 0.308 | 0.116 | 0.321 | −0.010 |

| Survey year | |||||

| 2010 | 0.261 | 0.439 | 0.223 | 0.416 | 0.038 |

| 2013 | 0.297 | 0.457 | 0.274 | 0.446 | 0.023 |

| 2016 | 0.248 | 0.432 | 0.255 | 0.436 | −0.007 |

| 2019 | 0.193 | 0.395 | 0.248 | 0.432 | −0.055 |

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Gender | ||||

| Male | 45.05 | 13.18 | 0 | 89 |

| Female | 31.92 | 13.81 | 0 | 88 |

| (2) Age | ||||

| Aged 16–29 | 40.52 | 16.25 | 0 | 89 |

| Aged 30–49 | 41.22 | 15.17 | 0 | 89 |

| Aged 50 and above | 36.95 | 14.31 | 0 | 89 |

| (3) Education | ||||

| Low education | 38.09 | 14.41 | 0 | 89 |

| Middle education | 36.29 | 15.06 | 0 | 89 |

| High education | 43.24 | 15.03 | 0 | 89 |

| (4) Occupation | ||||

| Non-managers | 38.58 | 15.04 | 0 | 89 |

| Managers | 46.32 | 11.75 | 0 | 85 |

| (5) Region | ||||

| Small cities | 39.14 | 15.46 | 0 | 89 |

| Large cities | 39.09 | 14.40 | 0 | 88 |

| (6) Employment status | ||||

| Non-Regular workers | 28.43 | 12.91 | 0 | 88 |

| Regular workers | 45.81 | 11.92 | 0 | 89 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | 0.249 | *** | −0.155 | *** | −0.187 | *** | −0.175 | *** | −0.158 | *** |

| (3.04) | (−10.69) | (−14.45) | (−14.3) | (−13.07) | ||||||

| WH | −0.038 | *** | ||||||||

| (−7.33) | ||||||||||

| WH*Regular | −0.047 | *** | ||||||||

| (−10.45) | ||||||||||

| WH2 | 0.001 | *** | ||||||||

| (6.45) | ||||||||||

| WH2*Regular | 0.001 | *** | ||||||||

| (6.26) | ||||||||||

| WH3 | −0.000 | *** | ||||||||

| (−4.25) | ||||||||||

| WH2*Regular | 0.000 | ** | ||||||||

| (2.07) | ||||||||||

| Ref. 45WH | ||||||||||

| 40WH | 0.218 | *** | ||||||||

| (7.36) | ||||||||||

| 40WH*Regular | 0.105 | *** | ||||||||

| (3.20) | ||||||||||

| 50WH | 0.386 | *** | ||||||||

| (9.01) | ||||||||||

| 50WH*Regular | −0.125 | *** | ||||||||

| (−2.76) | ||||||||||

| 55WH | 0.472 | *** | ||||||||

| (7.79) | ||||||||||

| 55WH*Regular | −0.086 | |||||||||

| (−1.36) | ||||||||||

| 60WH | 0.617 | *** | ||||||||

| (8.30) | ||||||||||

| 60WH*Regular | −0.238 | *** | ||||||||

| (−3.08) | ||||||||||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Number of Observations | 549,524 | 549,524 | 549,524 | 549,524 | 549,524 | |||||

| Adjuster R-square | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||||

| Log Likelihood | −1,566,039 | −1,566,407 | −1,566,274 | −1,566,217 | −1,566,265 | |||||

| F statistics | 42.44 | 16.68 | 28.79 | 33.96 | 29.55 | |||||

| Prob>F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40WH | 50WH | 55WH | 60WH | |||||

| Female | −0.462 | *** | −0.512 | *** | −0.559 | *** | −0.609 | *** |

| (−17.65) | (−17.71) | (−15.80) | (−15.05) | |||||

| Ln age | −0.689 | *** | −0.811 | *** | −0.720 | *** | −0.737 | *** |

| (−22.45) | (−25.94) | (−20.65) | (−19.71) | |||||

| Having a spouse | −0.190 | *** | −0.173 | *** | −0.133 | *** | −0.123 | ** |

| (−6.17) | (−5.02) | (−3.13) | (−2.51) | |||||

| Ln family income | 0.198 | *** | 0.236 | *** | 0.199 | *** | 0.174 | *** |

| (13.49) | (14.85) | (10.75) | (8.62) | |||||

| Occupation [Manager] | ||||||||

| Professional | −0.081 | *** | −0.089 | *** | −0.053 | * | −0.056 | * |

| (−3.21) | (−3.56) | (−1.88) | (−1.84) | |||||

| Clerk | −0.381 | *** | −0.462 | *** | −0.456 | *** | −0.450 | *** |

| (−13.36) | (−15.51) | (−12.95) | (−11.41) | |||||

| Sales workers | 0.145 | *** | 0.169 | *** | 0.209 | *** | 0.230 | *** |

| (4.26) | (5.01) | (5.68) | (5.82) | |||||

| Service workers | −0.069 | ** | −0.053 | 0.029 | 0.085 | ** | ||

| (−2.14) | (−1.64) | (0.79) | (2.16) | |||||

| Protective service workers | −0.258 | *** | −0.339 | *** | −0.165 | *** | −0.085 | |

| (−4.79) | (−6.20) | (−2.76) | (−1.34) | |||||

| Agriculture, forestry and fishery workers | 0.025 | −0.124 | 0.029 | −0.002 | ||||

| (0.30) | (−1.44) | (0.30) | (−0.02) | |||||

| Elementary occupations | −0.039 | −0.165 | *** | −0.060 | ** | −0.026 | ||

| (−1.43) | (−6.05) | (−1.96) | (−0.78) | |||||

| Not elsewhere classified | −0.264 | *** | −0.230 | *** | −0.146 | ** | −0.104 | |

| (−5.04) | (−4.24) | (−2.38) | (−1.58) | |||||

| Firm size (number of employees) | ||||||||

| 5–29 | 0.114 | *** | 0.138 | *** | 0.190 | *** | 0.178 | *** |

| (2.86) | (3.17) | (3.70) | (3.18) | |||||

| 30–99 | 0.067 | * | 0.153 | *** | 0.191 | *** | 0.181 | *** |

| (1.66) | (3.48) | (3.70) | (3.21) | |||||

| 100–299 | −0.033 | 0.098 | ** | 0.092 | * | 0.043 | ||

| (−0.82) | (2.21) | (1.75) | (0.76) | |||||

| 200–499 | −0.060 | 0.071 | 0.058 | 0.016 | ||||

| (−1.33) | (1.46) | (1.00) | (0.26) | |||||

| 500–999 | −0.067 | 0.098 | ** | 0.025 | −0.047 | |||

| (−1.48) | (2.03) | (0.44) | (−0.76) | |||||

| 1000–4999 | −0.087 | ** | 0.027 | 0.006 | −0.025 | |||

| (−2.06) | (0.58) | (0.10) | (−0.43) | |||||

| 5000- | −0.130 | *** | −0.024 | −0.056 | −0.133 | ** | ||

| (−3.09) | (−0.53) | (−1.05) | (−2.26) | |||||

| Government office | 0.024 | 0.240 | *** | 0.336 | *** | 0.300 | *** | |

| (0.56) | (5.15) | (6.20) | (5.05) | |||||

| Spouse’s employment status [non-work] | ||||||||

| Regular worker | −0.102 | *** | −0.115 | *** | −0.128 | *** | −0.111 | *** |

| (−5.25) | (−5.69) | (−5.57) | (−4.39) | |||||

| Part-time | 0.054 | *** | 0.007 | −0.024 | 0.017 | |||

| (2.79) | (0.37) | (−1.10) | (0.72) | |||||

| Temporary worker | 0.022 | −0.006 | 0.012 | 0.061 | ||||

| (0.42) | (−0.12) | (0.20) | (0.98) | |||||

| Dispatched worker | 0.048 | 0.072 | 0.022 | 0.118 | ||||

| (0.60) | (0.91) | (0.25) | (1.29) | |||||

| Contract worker | 0.019 | 0.060 | 0.016 | −0.019 | ||||

| (0.40) | (1.27) | (0.30) | (−0.32) | |||||

| Entrusted worker | 0.015 | 0.009 | 0.021 | 0.018 | ||||

| (0.20) | (0.13) | (0.26) | (0.20) | |||||

| Other | −0.004 | 0.094 | 0.070 | 0.050 | ||||

| (−0.03) | (0.84) | (0.57) | (0.36) | |||||

| Number of children | 0.027 | −0.015 | 0.057 | 0.102 | * | |||

| (0.53) | (−0.29) | (0.99) | (1.68) | |||||

| City Scale [Large city] (thousands) | ||||||||

| Population 150 | −0.047 | ** | −0.070 | *** | −0.046 | ** | −0.073 | *** |

| (−2.50) | (−3.63) | (−2.15) | (−3.15) | |||||

| Population 50−149 | −0.080 | *** | −0.111 | *** | −0.103 | *** | −0.118 | *** |

| (4.12) | (−5.55) | (−4.55) | (−4.84) | |||||

| Population 149 or less | −0.101 | *** | −0.169 | *** | −0.163 | *** | −0.234 | *** |

| (−3.57) | (−5.75) | (−4.82) | (−6.21) | |||||

| County | −0.097 | *** | −0.148 | *** | −0.126 | *** | −0.173 | *** |

| (−3.89) | (−5.74) | (−4.30) | (−5.38) | |||||

| Constant term | 2.480 | *** | 2.153 | *** | 1.435 | *** | 1.514 | *** |

| (17.94) | (15.33) | (9.03) | (8.76) | |||||

| Number of observations | 35,870 | 35,870 | 35,870 | 35,870 | ||||

| Pseudo-R-Square | 0.063 | 0.071 | 0.067 | 0.073 | ||||

| Log Likelihood | −23,109 | −21,585 | −16,013 | −13,163 | ||||

| Chi2 Statistics | 2868.900 | 2830.200 | 1907.500 | 1613.600 | ||||

| Prob > Chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40WH | 50WH | 55WH | 60WH | |||||

| Female | −0.200 | *** | −0.317 | *** | −0.307 | *** | −0.432 | *** |

| (−4.68) | (−5.65) | (−4.15) | (−4.91) | |||||

| Ln age | −0.699 | *** | −0.762 | *** | −0.690 | *** | −0.707 | *** |

| (−13.79) | (−12.17) | (−8.80) | (−7.80) | |||||

| Spouse of household | −0.357 | *** | −0.207 | *** | −0.160 | * | −0.149 | |

| (−7.40) | (−3.21) | (−1.86) | (−1.41) | |||||

| Ln family income | 0.102 | *** | 0.115 | *** | 0.125 | *** | 0.106 | ** |

| (4.69) | (4.15) | (3.55) | (2.48) | |||||

| Type of work [Part-time] | ||||||||

| Dispatched worker | 0.010 | −0.020 | 0.050 | −0.070 | ||||

| (0.21) | (−0.37) | (0.68) | (−0.76) | |||||

| Contract worker | 0.450 | *** | 0.380 | *** | 0.350 | *** | 0.330 | *** |

| (8.16) | (5.60) | (3.83) | (3.08) | |||||

| Entrusted Worker | 0.660 | *** | 0.520 | *** | 0.460 | *** | 0.390 | *** |

| (19.65) | (12.18) | (8.45) | (5.95) | |||||

| Occupation [Manager] | ||||||||

| Professional | 0.069 | 0.130 | 0.032 | 0.077 | ||||

| (0.76) | (1.17) | (0.23) | (0.44) | |||||

| Clerk | −0.060 | −0.073 | −0.218 | −0.306 | ||||

| (−0.64) | (−0.62) | (−1.44) | (−1.53) | |||||

| Sale | 0.038 | 0.048 | 0.080 | 0.162 | ||||

| (0.39) | (0.39) | (0.52) | (0.84) | |||||

| Service | 0.101 | 0.136 | 0.195 | 0.310 | * | |||

| (1.11) | (1.20) | (1.38) | (1.75) | |||||

| Security | 0.375 | *** | 0.417 | *** | 0.360 | ** | 0.435 | ** |

| (3.04) | (2.85) | (1.97) | (2.03) | |||||

| Agriculture, forestry and Fishery workers | 0.341 | ** | 0.394 | ** | 0.285 | −0.132 | ||

| (2.52) | (2.38) | (1.37) | (−0.42) | |||||

| Elementary | 0.356 | *** | 0.272 | ** | 0.210 | 0.242 | ||

| (3.97) | (2.45) | (1.51) | (1.40) | |||||

| Not elsewhere classified | 0.036 | 0.022 | 0.019 | 0.135 | ||||

| (0.35) | (0.17) | (0.12) | (0.68) | |||||

| Firm size [1–4] (number of employees) | ||||||||

| 5–29 | −0.075 | −0.123 | −0.145 | −0.053 | ||||

| (−1.26) | (−1.61) | (−1.52) | (−0.45) | |||||

| 30–99 | −0.017 | −0.036 | −0.063 | −0.013 | ||||

| (−0.27) | (−0.48) | (−0.66) | (−0.11) | |||||

| 100–299 | −0.018 | −0.058 | −0.083 | −0.080 | ||||

| (−0.29) | (−0.73) | (−0.84) | (−0.65) | |||||

| 200–499 | −0.033 | −0.096 | −0.177 | −0.128 | ||||

| (−0.44) | (−1.02) | (−1.48) | (−0.89) | |||||

| 500–999 | −0.025 | −0.074 | −0.231 | ** | −0.218 | |||

| (−0.35) | (−0.81) | (−1.97) | (−1.52) | |||||

| 1000–4999 | −0.072 | −0.146 | * | −0.255 | ** | −0.292 | ** | |

| (−1.07) | (−1.67) | (−2.28) | (−2.09) | |||||

| 5000– | −0.222 | *** | −0.212 | ** | −0.317 | *** | −0.348 | ** |

| (−3.11) | (−2.35) | (−2.70) | (−2.30) | |||||

| Government office | −0.560 | *** | −0.347 | *** | −0.224 | * | −0.230 | |

| (−6.57) | (−3.35) | (−1.75) | (−1.44) | |||||

| Spouse’s employment status [non-work] | ||||||||

| Regular worker | −0.226 | *** | −0.284 | *** | −0.297 | *** | −0.282 | *** |

| (−5.63) | (−5.43) | (−4.32) | (−3.34) | |||||

| Part-time | 0.058 | 0.076 | 0.071 | 0.042 | ||||

| (1.32) | (1.44) | (1.08) | (0.55) | |||||

| Temporary worker | 0.060 | −0.038 | 0.044 | 0.184 | ||||

| (0.68) | (−0.33) | (0.32) | (1.26) | |||||

| Dispatched worker | 0.060 | 0.224 | 0.008 | −0.397 | ||||

| (0.38) | (1.30) | (0.04) | (−1.04) | |||||

| Contract worker | −0.012 | −0.041 | 0.024 | −0.071 | ||||

| (−0.17) | (−0.45) | (0.22) | (−0.51) | |||||

| Entrusted worker | −0.106 | −0.060 | −0.067 | −0.099 | ||||

| (−0.92) | (−0.43) | (−0.37) | (−0.42) | |||||

| Other | −0.243 | −0.007 | ||||||

| (−1.07) | (−0.03) | |||||||

| Number of children | 0.088 | 0.202 | * | 0.204 | 0.193 | |||

| (0.99) | (1.85) | (1.52) | (1.16) | |||||

| City Scale [Large city] (thousands) | ||||||||

| Population 150 | 0.060 | * | 0.006 | 0.049 | 0.007 | |||

| (1.73) | (0.15) | (0.87) | (0.10) | |||||

| Population 50–149 | 0.083 | ** | −0.020 | −0.037 | −0.054 | |||

| (2.35) | (0.43) | (−0.62) | (−0.77) | |||||

| Population 149 or less | 0.128 | ** | 0.083 | 0.078 | −0.051 | |||

| (2.57) | (1.32) | (0.95) | (0.49) | |||||

| County | 0.196 | *** | 0.097 | * | 0.161 | ** | 0.086 | |

| (4.46) | (1.73) | (2.30) | (1.04) | |||||

| Constant term | 1.422 | *** | 1.249 | *** | 0.540 | 0.677 | ||

| (5.93) | (4.22) | (1.48) | (1.58) | |||||

| Number of observations | 21,884 | 21,884 | 21,798 | 21,798 | ||||

| Pseudo-R-Square | 0.135 | 0.122 | 0.110 | 0.124 | ||||

| Log Likelihood | −6278 | −3577 | −2030 | −1353 | ||||

| Chi2 Statistics | 1803.500 | 848.600 | 423.300 | 303.100 | ||||

| Prob>Chi2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| (1) | (2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE. | Coef. | SE. | |

| (1) 50WH | ||||

| ATT | 0.306 | 0.048 | 0.403 | 0.051 |

| Covariates | No | Yes | ||

| (2) 55WH | ||||

| ATT | 0.353 | 0.059 | 0.454 | 0.061 |

| Covariates | No | Yes | ||

| (3) 60WH | ||||

| ATT | 0.324 | 0.06 | 0.435 | 0.069 |

| Covariates | No | Yes | ||

| (1) Regular | (2) No-Regular | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE. | Coef. | SE. | |||

| ATT | 0.457 | *** | 0.061 | 0.518 | ** | 0.277 |

| Covariates | Yes | Yes | ||||

| (a) gender | |||||||||

| Men | (2) Women | ||||||||

| Coef. | SE. | Coef. | SE. | ||||||

| ATT | 0.43 | *** | 0.063 | 0.718 | *** | 0.16 | |||

| Covariates | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| (b) occupation | |||||||||

| (1) Manager | (2) Non-Manager | ||||||||

| Coef. | SE. | Coef. | SE. | ||||||

| ATT | 0.767 | *** | 0.161 | 0.43 | *** | 0.063 | |||

| Covariates | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| (c) firm size | |||||||||

| (1) Small (1-99) | (2) Middle (100–299) | (3) Large (300 or more) | |||||||

| Coef. | SE. | Coef. | SE. | Coef. | SE. | ||||

| ATT | 0.547 | *** | 0.135 | 0.285 | *** | 0.105 | 0.612 | *** | 0.098 |

| Covariates | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| (d) city size | |||||||||

| (1) Large city | (2) Middle-size city | (3) Small-size city | |||||||

| Coef. | SE. | Coef. | SE. | Coef. | SE. | ||||

| ATT | 0.415 | *** | 0.078 | 0.531 | *** | 0.089 | 0.547 | *** | 0.135 |

| Covariates | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, X.; Kawakami, A.; Inui, T. Impact of Long Working Hours on Mental Health Status in Japan: Evidence from a National Representative Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070842

Ma X, Kawakami A, Inui T. Impact of Long Working Hours on Mental Health Status in Japan: Evidence from a National Representative Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(7):842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070842

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Xinxin, Atushi Kawakami, and Tomohiko Inui. 2024. "Impact of Long Working Hours on Mental Health Status in Japan: Evidence from a National Representative Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 7: 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070842

APA StyleMa, X., Kawakami, A., & Inui, T. (2024). Impact of Long Working Hours on Mental Health Status in Japan: Evidence from a National Representative Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(7), 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070842