Raynaud’s Phenomenon of the Nipple: Epidemiological, Clinical, Pathophysiological, and Therapeutic Characterization

Abstract

1. Introduction

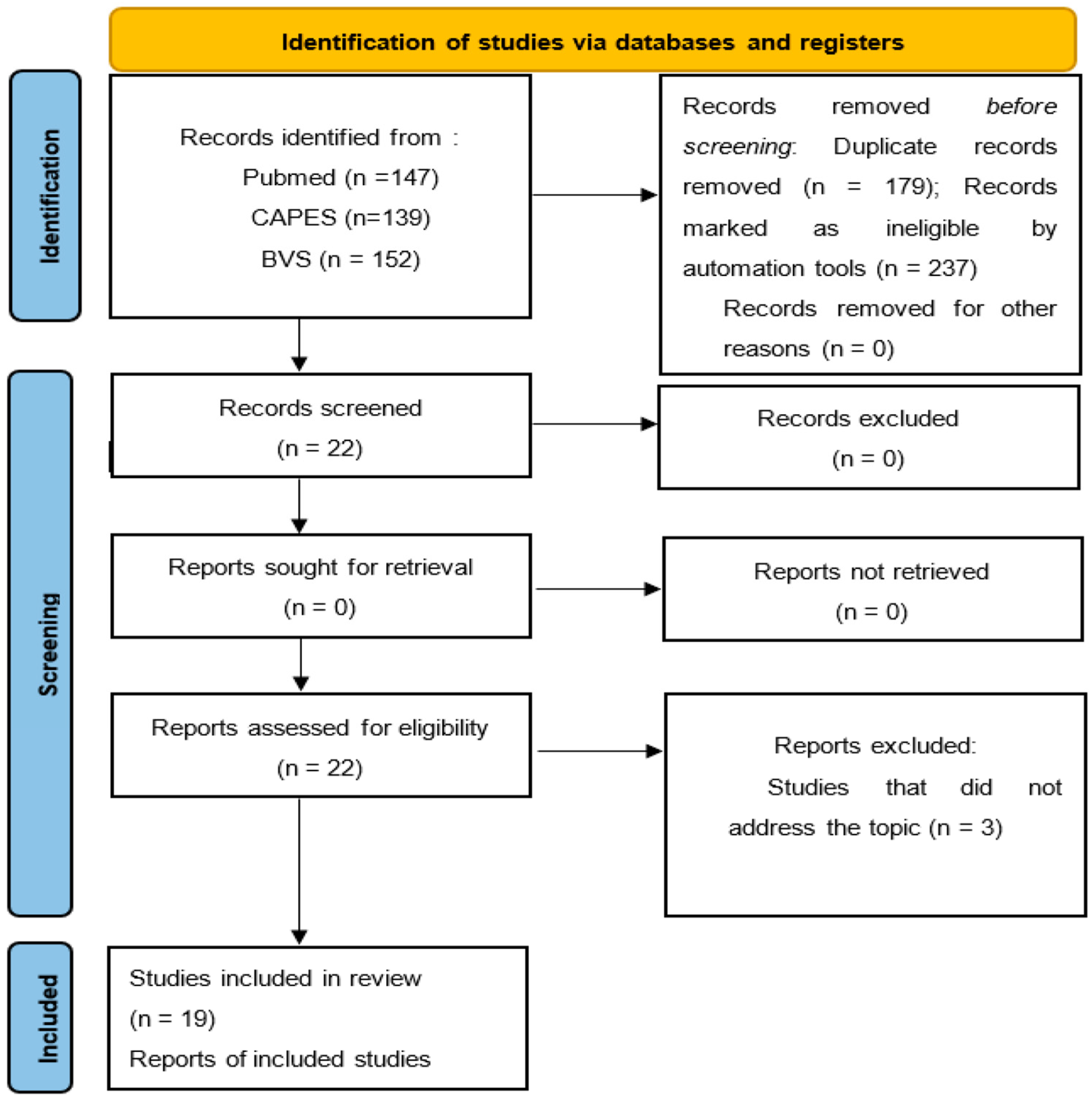

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

| Author (Year)-Country | Study Type- Quality Assessment | Patients (n) | Age (Years) | When RP Appears | Type of RP | Type of Color Change | Previous Clinical Symptoms | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrando et al. (2023) [3] - Spain | Case report - Fair | 1 | 39 | 1 week postpartum and 12 months postpartum | Secondary | Unspecified | Yes | Nifedipine |

| Morino and Winn (2007) [4] - USA | Case report - Fair | 1 | 24 | 27 days postpartum | Primary | Triphasic | Yes | Non- Pharmacological |

| McGuinness and Cording (2013) [5] - England | Case report - Good | 1 | 37 | 34 weeks of pregnancy | Secondary | Triphasic | Yes | Weaning Labetalol postpartum |

| Holmen and Backe (2009) [8] - Norway | Case report - Good | 1 | 25 | Beginning of second trimester of pregnancy | Primary | Triphasic | Yes | Nifedipine |

| Lawlor-Smith and Lawlor-Smith (1997) [9] - Australia | Case series - Fair | 5 | 28 | 1 week postpartum | Primary | Triphasic | No | Unspecified |

| 30 | 3 weeks postpartum | Primary | Triphasic | Yes | Unspecified | |||

| 32 | 2 weeks postpartum | Primary | Biphasic | Yes | Unspecified | |||

| 32 | 1 week postpartum | Primary | Biphasic | No | Unspecified | |||

| 30 | day postpartum | Primary | Biphasic | No | Unspecified | |||

| Gallego and Aleshaki (2020) [10] - USA | Case report - Good | 1 | 36 | 3 weeks postpartum | Primary | Triphasic | No | Nifedipine and Pregabalin |

| Hardwick, McMurtrie and Melrose (2002) [15] - UK | Case report - Fair | 1 | 41 | 16 weeks of pregnancy | Secondary | Biphasic | No | Non- Pharmacological |

| Stammler, Lawall and Diehm (2003) [16] - Germany | Case report - Good | 1 | 38 | 13 weeks of pregnancy | Secondary | Triphasic | Yes | LMWH and AAS |

| Jansen and Sampene (2019) [17] - USA | Case series - Good | 2 | 40 | 17 weeks of pregnancy | Secondary | Triphasic | Yes | Substitution of Labetalol for Nifedipine |

| 32 | Postpartum | Primary | Triphasic | Yes | Non- Pharmacological | |||

| O’ Sullivan and Keith (2011) [19] - USA | Case report - Good | 1 | 32 | Immediately postpartum | Primary | Biphasic | Yes (previous diagnostic) | Nifedipine and Nitroglycerin ointment |

| Wu, Chason and Wong (2012) [20] - USA | Case series - Good | 2 | 23 | 3 months postpartum | Primary | Biphasic | No | Nifedipine |

| 32 | Postpartum | Primary | Biphasic | Yes | Nifedipine | |||

| Laursen and Rørbye (2013) [21] - Denmark | Case report - Fair | 1 | 33 | 35 weeks of pregnancy | Primary | Triphasic | Yes | Calcium channel blocker |

| Di Como et al. (2020) [22] - USA | Case report - Fair | 1 | 38 | 33 weeks of pregnancy | Primary | Triphasic | Yes | Non- Pharmacological |

| Page and McKenna (2006) [31] - USA | Case report - Good | 1 | 26 | 5 weeks postpartum | Primary | Biphasic | No | Nifedipine |

| Javier et al. (2012) [32] - Spain | Case report - Fair | 1 | 28 | 2 weeks postpartum | Primary | Biphasic | No | Nifedipine |

| Quental et al. (2023) [33] - Portugal | Case report - Good | 1 | 29 | 2 months postpartum | Primary | Biphasic | No | Nifedipine |

| Anderson, Held and Wright (2004) [34] - USA | Case series - Good | 3 | 28 | 3 weeks postpartum | Primary | Unspecified | No | Refused (Nifedipine) |

| 31 | 2 weeks postpartum | Primary | Biphasic | No | Non- Pharmacological | |||

| 35 | Immediately postpartum | Primary | Biphasic | No | Nifedipine | |||

| Abrantes et al. (2016) [38] - Portugal | Case series - Good | 3 | 39 | 2 weeks postpartum | Primary | Triphasic | No | Nifedipine |

| 30 | 2 weeks postpartum | Primary | Triphasic | No | Refused | |||

| 31 | 6 weeks postpartum | Primary | Triphasic | No | Non- Pharmacological |

4. Discussion

4.1. Epidemiological, Pathophysiological, and Clinical Characterization of Raynaud’s Phenomenon of the Nipple

4.2. Treatment of Raynaud’s Phenomenon of the Nipple

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Devgire, V.; Hughes, M. Raynaud’s Phenomenon. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2019, 80, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrick, A.L.; Wigley, F.M. Raynaud’s Phenomenon. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 34, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Ferrer, J.G.M.; Puig, F.S.; Garcia, C.V. Una paciente con fenómeno de Raynaud del pezón e hipertiroidismo. Rev. Clin. Med. Fam. 2023, 16, 304–306. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morino, C.; Winn, S.M. Raynaud’s Phenomenon of the Nipples: An Elusive Diagnosis. J. Hum. Lact. 2007, 23, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, N.; Cording, V. Raynaud’s Phenomenon of the Nipple Associated with Labetalol Use. J. Hum. Lact. 2012, 29, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauling, J.D.; Hughes, M.; Pope, J.E. Raynaud’s Phenomenon-an update on diagnosis, classification and management. Clin. Rheumatol. 2019, 38, 3317–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, A.; Hughes, M. Raynaud’s Phenomenon. Clin. Med. 2020, 20, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmen, O.L.; Backe, B. An underdiagnosed cause of nipple pain presented on a camera phone. BMJ 2009, 339, b2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor-Smith, L.; Lawlor-Smith, C. Vasospasm of the nipple—A manifestation of Raynaud’s Phenomenon: Case reports. BMJ 1997, 314, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, H.; Aleshaki, J.S. Raynaud Phenomenon of the Nipple Successfully Treated With Nifedipine and Gabapentin. Cutis 2020, 105, E22–E23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, C.; Corrêa, M.J.U.; Andrade, L.E.C. Fenômeno de Raynaud. Rev. Bras. Reum. 2009, 49, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Garner, R.; Kumari, R.; Lanyon, P.; Doherty, M.; Zhang, W. Prevalence, risk factors and associations of primary Raynaud’s Phenomenon: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchon, B.; Pistorius, M.-A.; Beurrier, P.; De Faucal, P. Primary Raynaud’s Phenomenon. Age of onset and pathogenesis in a prospective study of 424 patients. Angiology 1994, 45, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, M.; Catharino, A.M.S.; Silveira, V.C.; Reis, C.H.M.; De Sant, M.; Cardoso, C.E., Jr. Raynaud’s Phenomenon after cold exposure: A case report. Int. J. Case Rep. Images 2021, 12, 101267Z01MO2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, J.C.R.; McMutrie, F.; Melrose, E.B. Raynaud’s syndrome of the nipple in pregnancy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2002, 102, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stammler, F.; Lawall, H.; Diehm, C. Repeated attacks of pain in the nipple of a pregnant woman. Unusual manifestation of Raynaud’s Phenomenon. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 2003, 128, 1825–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, S.; Sampene, K. Raynaud Phenomenon of the Nipple: An Under-Recognized Condition. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 133, 975–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrison, C.P. Nipple vasospasms, Raynaud’s syndrome, and nifedipine. J. Hum. Lact. 2002, 18, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, S.; Keith, M.P. Raynaud Phenomenon of the nipple: A rare finding in rheumatology clinic. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2011, 17, 371–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Chason, R.; Wong, M. Raynaud’s Phenomenon of the nipple. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 119, 447–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, J.B.; Rørbye, C. Raynaud’s Phenomenon of the papilla mammae caused by breastfeeding. Ugeskr. Laeger. 2015, 177, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Di Como, J.; Tan, S.; Weaver, M.; Edmonson, D.; Gass, J.S. Nipple pain: Raynaud’s beyond fingers and toes. Breast J. 2020, 26, 2045–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wigley, F.M.; Flavahan, N.A. Raynaud’s Phenomenon. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, J.C.; Dowd, P.M. Raynaud’s disease. Lancet 2003, 361, 2078–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, A.; Snyder, B. Raynaud Phenomenon. Am. J. Nurs. 2005, 105, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeRoy, E.C.; Medsger, T.A., Jr. Raynaud’s Phenomenon: A proposal for classification. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 1992, 10, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gayraud, M. Raynaud’s Phenomenon. Jt. Bone Spine 2007, 74, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, M.E.; Heller, M.M.; Stone, H.F.; Murase, J.E. Raynaud Phenomenon of the nipple in breastfeeding mothers: An underdiagnosed cause of nipple pain. JAMA Dermatol. 2013, 149, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, J.P.; Marshall, J.M. Mechanisms of Raynaud’s disease. Vasc. Med. 2005, 10, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavahan, N.A. A vascular mechanistic approach to understanding Raynaud Phenomenon. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2015, 11, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.M.; McKenna, D.S. Vasospasm of the nipple presenting as painful lactation. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 108, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, F.J.M.; Martos, M.D.C. Fenómeno de Raynaud y el amamantamienteo doloroso. Rev. Clin. Med. Fam. 2012, 5, 51–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quental, C.; Brito, D.B.; Sobral, J.M.; Macedo, A.M. Raynaud Phenomenon of the Nipple: A Clinical Case Report. J. Fam. Reprod. Health 2023, 17, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.E.; Held, N.; Wright, K. Raynaud’s Phenomenon of the nipple: A treatable cause of painful breastfeeding. Pediatrics 2004, 113, e360–e364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neville, M.C.; Anderson, S.M.; McManaman, J.L.; Badger, T.M.; Bunik, M.; Contractor, N.; Crume, T.; Dabelea, D.; Donovan, S.M.; Forman, N.; et al. Lactation and neonatal nutrition: Defining and refining the critical questions. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2012, 17, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, P.O. Drug Treatment of Raynaud’s Phenomenon of the Nipple. Breastfeed. Med. 2020, 15, 686–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrantes, A.; Djokovic, D.; Bastos, C.; Veca, P. Fenómeno de Raynaud do mamilo em mulheres a amamentar: Relato de três casos clínicos. Rev. Port. Med. Geral Fam. 2006, 32, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.E.; Pope, J.E. Calcium channel blockers for primary Raynaud’s Phenomenon: A meta-analysis. Rheumatology 2005, 44, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moreira, T.G.; Castro, G.M.; Gonçalves Júnior, J. Raynaud’s Phenomenon of the Nipple: Epidemiological, Clinical, Pathophysiological, and Therapeutic Characterization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070849

Moreira TG, Castro GM, Gonçalves Júnior J. Raynaud’s Phenomenon of the Nipple: Epidemiological, Clinical, Pathophysiological, and Therapeutic Characterization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(7):849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070849

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreira, Thaís Gomes, Giovana Mamede Castro, and Jucier Gonçalves Júnior. 2024. "Raynaud’s Phenomenon of the Nipple: Epidemiological, Clinical, Pathophysiological, and Therapeutic Characterization" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 7: 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070849

APA StyleMoreira, T. G., Castro, G. M., & Gonçalves Júnior, J. (2024). Raynaud’s Phenomenon of the Nipple: Epidemiological, Clinical, Pathophysiological, and Therapeutic Characterization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(7), 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070849