Dignity of Work and at Work: The Relationship between Workplace Dignity and Health among Latino Immigrants during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Workplace Vulnerabilities for Latino Immigrants

1.2. Our Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Community Partner

2.3. Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Ethics

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Theme 1: Dignity at Work

3.3. Dignity of Work

3.4. Effects of Dignity on Health

4. Discussion

4.1. Denial of Workplace Dignity Leads to Adverse Mental and Physical Health Outcomes

4.2. Expanding the Paradigm on Work and Health to Include Workplace Dignity

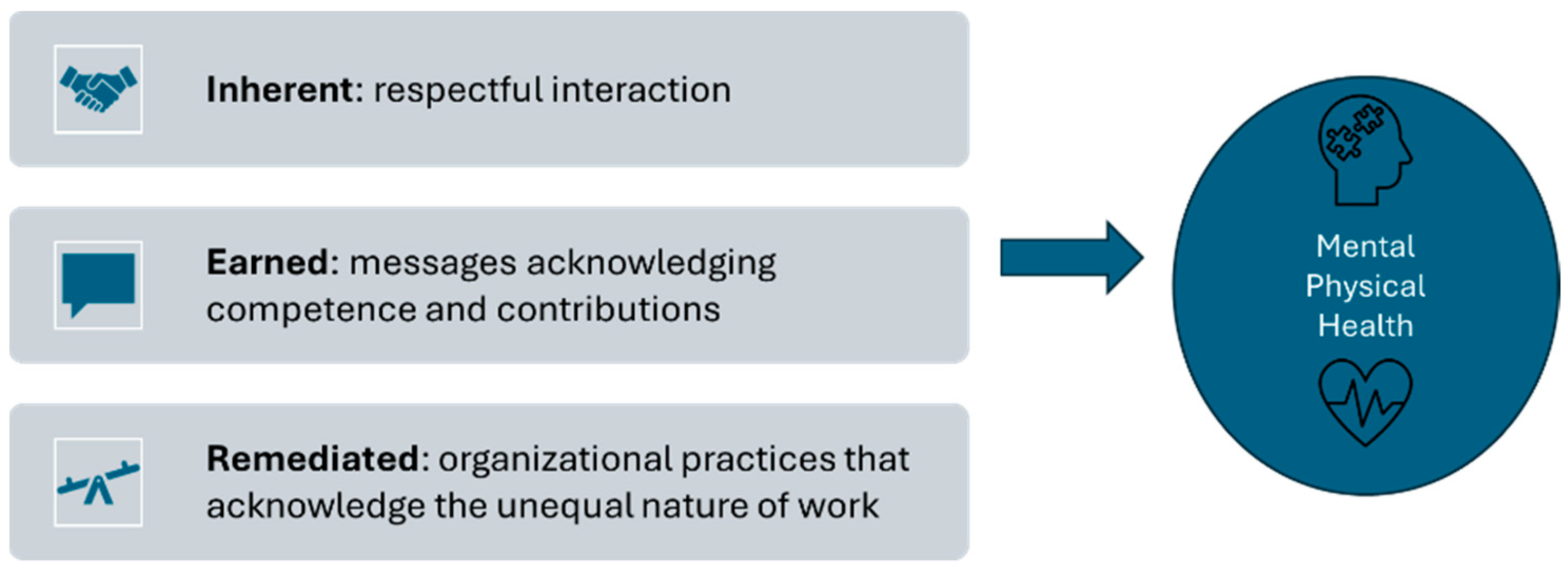

4.3. A New Conceptual Model on Workplace Dignity and Health for Immigrants

4.4. Policy Implications

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cantos, V.D.; Rebolledo, P.A. Structural vulnerability to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) among latinx communities in the United States. In Clinical Infectious Diseases; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; Volume 73, pp. S136–S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death by Race/Ethnicity; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Perry, B.L.; Aronson, B.; Pescosolido, B.A. Pandemic precarity: COVID-19 is exposing and exacerbating inequalities in the American heartland. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2020685118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamarripa, R.; Roque, L. Latinos Face Disproportionate Health and Economic Impacts from COVID-19; Center for American Progress: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/latinos-face-disproportionate-health-economic-impacts-covid-19/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Noe-Bustamante, L.; Krogstad, J.M.; Lopez, M.H. During the Pandemic, Latinos Have Experienced Widespread Financial Challenges. 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/race-ethnicity/2021/07/15/latinos-have-experienced-widespread-financial-challenges-during-the-pandemic/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Frank, J.; Mustard, C.; Smith, P.; Siddiqi, A.; Cheng, Y.; Burdorf, A.; Rugulies, R. Work as a social determinant of health in high-income countries: Past, present, and future. Lancet 2023, 402, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Rugulies, R.; Aust, B.; Greiner, B.A.; Arensman, E.; Kawakami, N.; LaMontagne, A.D.; Madsen, I.E. Work-related causes of mental health conditions and interventions for their improvement in workplaces. Lancet 2023, 402, 1368–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health. The Role of Work in Health Disparities in the U.S.: PAR-21-275; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 25 June 2021. Available online: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-21-275.html (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Lucas, K. Workplace Dignity: Communicating Inherent, Earned, and Remediated Dignity. J. Manag. Stud. 2015, 52, 621–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzmer, D.; Klein, E. (Eds.) The Concept of Human Dignity in Human Rights Discourse; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson, R. Dignity at Work. In Dignity at Work; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, A. Dignity at work: Broadening the agenda. Organization 2007, 14, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, G. Recognition, Reification, and Practices of Forgetting: Ethical Implications of Human Resource Management. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Liang, D.; Anjum, M.A.; Durrani, D.K. Does dignity matter? The effects of workplace dignity on organization-based self-esteem and discretionary work effort. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 4732–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, K.R.; Flores-Miller, A. Lessons We’ve Learned—COVID-19 and the Undocumented Latinx Community. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, B.A.; Blustein, D.L. Precarious work and workplace dignity during COVID-19: A longitudinal study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2022, 136, 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgard, S.A.; Brand, J.E.; House, J.S. Toward a better estimation of the effect of job loss on health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2007, 48, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, P.C.; Crimmins, E.M.; Hurd, M.D. The effect of job loss on health: Evidence from biomarkers. Labour Econ. 2016, 41, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaller, J.; Stevens, A.H. Short-run effects of job loss on health conditions, health insurance, and health care utilization. J. Health Econ. 2015, 43, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleaveland, C.L.; Frankenfeld, C.L. Household Financial Hardship Factors Are Strongly Associated with Poorer Latino Mental Health During COVID-19. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 10, 1823–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czeisler, M.É.; Marynak, K.; Clarke, K.E.N.; Salah, Z.; Shakya, I.; Thierry, J.M.; Ali, N.; McMillan, H.; Wiley, J.F.; Weaver, M.D.; et al. Delay or Avoidance of Medical Care Because of COVID-19–Related Concerns—United States, June 2020. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1250–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcini, L.M.; Rosenfeld, J.; Kneese, G.; Bondurant, R.G.; Kanzler, K.E. Dealing with distress from the COVID-19 pandemic: Mental health stressors and coping strategies in vulnerable latinx communities. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Aguinaga, B.; Dominguez, M.S.; Manzano, S. Immigration and gender as social determinants of mental health during the COVID-19 outbreak: The case of us latina/os. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman-Mellor, S.; Plancarte, V.; Perez-Lua, F.; Payán, D.D.; De Trinidad Young, M.-E. Mental health among rural Latino immigrants during the COVID-19 pandemic. SSM—Ment. Health 2023, 3, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthew, O.O.; Monaghan, P.F.; Luque, J.S. The Novel Coronavirus and Undocumented Farmworkers in the United States. New Solut. 2021, 31, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis, J.; Franco-Paredes, C.; Henao-Martinez, A.F.; Krsak, M.; Zimmer, S.M. Structural vulnerability in the U.S. revealed in three waves of COVID-19. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 25–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, S.A.; Avalos, A.; Gray, M.; Hawthorne, K.M. High Level of Food Insecurity among Families with Children Seeking Routine Care at Federally Qualified Health Centers during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. J. Pediatr. X 2020, 4, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, I.; Rosenblum, M.R.; Baker, B.; Eastman, A. COVID-19 Vulnerability by Immigration Status: Status-Specific Risk Factors and Demographic Profiles. 2021. Available online: https://perma.cc/JZM9-RPZJ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Martínez, M.E.; Nodora, J.N.; Carvajal-Carmona, L.G. The dual pandemic of COVID-19 and systemic inequities in US Latino communities. Cancer 2021, 127, 1548–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A. Latino Immigrants Face an Uphill Battle to Economic Inclusion. National Equity Atlas, 9 August 2016. Available online: https://nationalequityatlas.org/data-in-action/latino-immigrants-economic-inclusion (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014, 129 (Suppl. 2), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A.; Leavell, J.; Collins, C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: Complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 69–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, A.; Kim, S.; Nam, J.; Rossin-Slater, M.; Ruhm, C.; Waldfogel, J. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to and use of paid family and medical leave: Evidence from four nationally representative datasets. Mon. Labor. Rev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raifman, J.R.; Raderman, W.; Skinner, A.; Hamad, R. Paid Leave Policies Can Help Keep Businesses Open and Food on Workers’ Tables. Health Affairs. 2021. Available online: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20211021.197121/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Pew Research Center. Estimates of U.S. Unauthorized Immigrant Population, by Metro Area, 2016 and 2007; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/interactives/unauthorized-immigrants-by-metro-area-table/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Stepler, R.; Lopez, M. Ranking the Latino Population in Metropolitan Areas; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/2016/09/08/5-ranking-the-latino-population-in-metropolitan-areas/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Migration Policy Institute. Profile of the Unauthorized Population: District of Columbia; Migration Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/us-immigration-policy-program-data-hub/unauthorized-immigrant-population-profiles (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Yamanis, T.; Morrissey, T.; Bochey, L.; Cañas, N.; Sol, C. “Hay que seguir en la lucha”: An FQHC’s Community Health Action Approach to Promoting Latinx Immigrants’ Individual and Community Resilience. Behav. Med. 2020, 46, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Esquer, M.E.; Gallardo, K.R.; Diamond, P.M. Predicting the Influence of Situational and Immigration Stress on Latino Day Laborers’ Workplace Injuries: An Exploratory Structural Equation Model. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2019, 21, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro, A.Y.; Kuhn, R.; Rodriguez, M.A.; Theodore, N.; Melendez, E.; Valenzuela, A. Beyond Occupational Hazards: Abuse of Day Laborers and Health. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2020, 22, 1172–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibekwe, L.N.; Atkinson, J.S.; Guerrero-Luera, R.; King, Y.A.; Rangel, M.L.; Fernández-Esquer, M.E. Perceived Discrimination and Injury at Work: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Latino Day Laborers. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 24, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathod, J.M. Danger and Dignity: Immigrant Day Laborers and Occupational Risk. Seton Hall Law Rev. 2016, 46, 813–882. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.A.; Rospenda, K.M.; Richman, J.A.; Minich, L.M. Race, racial discrimination, and the risk of work-related illness, injury, or assault: Findings from a national study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009, 51, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro-Ramos, A.Y.; Rodriguez, H.P. Immigration Policy Vulnerability Linked to Adverse Mental Health Among Latino Day Laborers. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 24, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, C.M.; Williams, E.C.; Ornelas, I.J. Help Wanted: Mental Health and Social Stressors Among Latino Day Laborers. Am. J. Men’s Health 2019, 13, 1557988319838424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubrich, M. On the frontlines: Protecting low-wage workers during COVID-19. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S186–S187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alonzo, K.T.; Johnson, S.; Fanfan, D. A Biobehavioral Approach to Understanding Obesity and the Development of Obesogenic Illnesses among Latino Immigrants in the United States. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2012, 14, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alonzo, K.T.; Sharma, M. Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise The influence of marianismo beliefs on physical activity of mid-life immigrant Latinas: A Photovoice study. Qual. Res. Sport Excercise 2010, 2, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaestner, R.; Pearson, J.A.; Keene, D.; Geronimus, A.T. Stress, allostatic load, and health of Mexican immigrants. Soc. Sci. Q. 2009, 90, 1089–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissen, B.; Angee, A.; Weinstein, M. Immigrant Construction Workers and Health and Safety: The South Florida Experience. Labor Stud. J. 2008, 33, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P.J.; Novak, N.L.; Lopez, W.D. U.S. Immigration Law Enforcement Practices and Health Inequities. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, 858–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnake-Mahl, A.S.; O’Leary, G.; Mullachery, P.H.; Skinner, A.; Kolker, J.; Diez Roux, A.V.; Raifman, J.R.; Bilal, U. Higher COVID-19 Vaccination and Narrower Disparities in US Cities with Paid Sick Leave Compared to Those Without. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 1565–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keisler-Starkey, K.; Bunch, L.N. Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2021 Current Population Reports. 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2022/demo/p60-278.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Dubay, L.; Aarons, J.; Brown, K.S.; Kenney, G.M. How Risk of Exposure to the Coronavirus at Work Varies by Race and Ethnicity and How to Protect the Health and Well-Being of Workers and Their Families. 2020. Available online: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/how-risk-exposure-coronavirus-work-varies-race-and-ethnicity-and-how-protect-health-and-well-being-workers-and-their-families (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Song, H.; McKenna, R.; Chen, A.T.; David, G.; Smith-McLallen, A. The impact of the non-essential business closure policy on Covid-19 infection rates. Int. J. Health Econ. Manag. 2021, 21, 387–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, J.L.; Salinas, M. Systemic racism and undocumented Latino migrant laborers during COVID-19: A narrative review and implications for improving occupational health. J. Migr. Health 2022, 5, 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. COVID-19 Vaccine Access, Information, and Experiences Among Hispanic Adults in the U.S. In KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor; Kaiser Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-access-information-experiences-hispanic-adults/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Rhodes, S.D.; Mann, L.; Simán, F.M.; Song, E.; Alonzo, J.; Downs, M.; Lawlor, E.; Martinez, O.; Sun, C.J.; O’Brien, M.C.; et al. The impact of local immigration enforcement policies on the health of immigrant Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, E.; Sanchez, G.; Juarez, M. Fear by association: Perceptions of anti-immigrant policy and health outcomes. J. Health Politics 2017, 42, 459–483. Available online: https://read.dukeupress.edu/jhppl/article-abstract/42/3/459/13888?casa_token=5fDygwD-Hd0AAAAA:oHB4TElDA4OOCqVyD-UNY2ZXPpiW0l8keaoCo0SCGsr8L0wfmEx9cLCuRfx74cyr7EZ0E6M (accessed on 20 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Yamanis, T.J.; Del Río-González, A.M.; Rapoport, L.; Norton, C.; Little, C.; Barker, S.L.; Ornelas, I.J. Understanding fear of deportation and its impact on healthcare access among immigrant latinx men who have sex with men. In Sexual and Gender Minority Health; Advances in Medical Sociology; Emerald Group Holdings Ltd.: Bingley, UK, 2021; Volume 21, pp. 103–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Selvin, E.; Aboagye, J.; Turkson-Ocran, R.A.; Li, X.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; Ahima, R.S.; Cooper, L.A. Hypertension, overweight/obesity, and diabetes among immigrants in the United States: An analysis of the 2010-2016 National Health Interview Survey. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsan, M.; Chandra, A.; Simon, K. The great unequalizer: Initial health effects of COVID-19 in the United States. J. Econ. Perspect. 2021, 35, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-H.; Glymour, M.; Riley, A.; Balmes, J.; Duchowny, K.; Harrison, R.; Matthay, E.; Bibbins-Domingo, K. Excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic among Californians 18–65 years of age, by occupational sector and occupation: March through November 2020. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, D.; Davis, L.; Kriebel, D. COVID-19 deaths by occupation, Massachusetts, March 1–July 31, 2020. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2021, 64, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanis, T.; Malik, M.; Del Río-González, A.M.; Wirtz, A.L.; Cooney, E.; Lujan, M.; Corado, R.; Poteat, T. Legal immigration status is associated with depressive symptoms among latina transgender women in Washington, DC. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, P.; Kuch, H.; Neuhaeuser, C.; Webster, E. Humiliation, Degradation, Dehumanization: Human Dignity Violated; Kaufmann, P., Kuch, H., Neuhaeuser, C., Webster, E., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, B.L.; Campbell, S.; Meyers, A.R.; Crum, D.A.; Mitchell, C.S.; Hutson, J.; Williams, D.L.; Senesie, S.S.; Gilani, Z.; Reynolds, S.; et al. Factors That Might Affect SARS-CoV-2 Transmission Among Foreign-Born and U.S.-Born Poultry Facility Workers—Maryland, May 2020. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1906–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, D.; Barab, J. Opinion|OSHA Can Do More to Protect Americans from COVID-19. The New York Times. 14 January 2022. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/14/opinion/supreme-court-vaccine-mandate-osha.html (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Berger, Z.D.; Evans, N.G.; Phelan, A.L.; Silverman, R.D. COVID-19: Control measures must be equitable and inclusive. BMJ 2020, 368, m1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, A.; Jackson, K.; Hamad, R. Effects of the 2021 Expanded Child Tax Credit on Adults’ Mental Health: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Health Aff. (Proj. Hope) 2023, 42, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, S.H.; Chen, L.; DeLew, N.; Sommers, B.D. COVID-19 Medicaid Continuous Enrollment Provision Yielded Gains in Postpartum Continuity of Coverage: Study examines Medicaid continuous enrollment on postpartum continuity of coverage. Health Aff. 2024, 43, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chatterjee, S. Financial hardship and depression experienced by pre-retirees during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mitigating role of stimulus payments. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2021, 30, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milczarek-Desai, S. Op-Ed: OSHA Has Long Failed to Protect Some of Our Most Vulnerable Workers. Los Angeles Times. 26 January 2022. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2022-01-26/osha-mandates-worker-safety (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Ornelas, I.; Yamanis, T.J.; Ruiz, R.A. The health of undocumented Latinx immigrants: What we know and future directions. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2020, 41, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanis, T. COVID Stimulus Checks: Does Victory Include Abandoning the Most Vulnerable? The Globe Post. 26 October 2021. Available online: https://theglobepost.com/2021/03/25/covid-stimulus-checks-undocumented/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Leibenluft, J.; Olinsky, B. Protecting Worker Safety and Economic Security during the COVID-19 Reopening. 2020. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/protecting-worker-safety-economic-security-covid-19-reopening/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

| Characteristic | Categories | Number of Participants | % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (n = 29) | 18–25 years | 4 | 13.8% |

| 26–49 years | 18 | 62.1% | |

| 50+ years | 7 | 24.1% | |

| Gender identity (n = 29) | Cisgender women | 15 | 51.7% |

| Cisgender men | 12 | 41.4% | |

| Transgender (male to female) | 2 | 6.9% | |

| Employment status during COVID-19 (n = 28) | Employed | 9 | 32.1% |

| Unemployed | 19 | 67.9% | |

| Place of residence (n = 29) | Washington, D.C. | 18 | 62.1% |

| Prince George’s County, MD | 11 | 37.9% | |

| Immigration status (n = 28) | Undocumented | 8 | 28.5% |

| TPS | 4 | 14.3% | |

| Permanent resident/citizen (≥5 years) | 7 | 25% | |

| Permanent resident/citizen (<5 years) | 1 | 3.6% | |

| Other | 5 | 17.9% | |

| Prefers not to respond | 3 | 10.7% | |

| Country of origin (n = 26) | El Salvador | 14 | 53.9% |

| Guatemala | 6 | 23.1% | |

| Mexico | 2 | 7.7% | |

| Honduras | 2 | 7.7% | |

| Dominican Republic | 1 | 3.8% | |

| Venezuela | 1 | 3.8% |

| Dignity Type | Lack of Dignity at Work | Lack of Dignity of Work |

|---|---|---|

| Inherent | social isolation; COVID-19 stigma at work | lack of government assistance perceived as lack of respect for immigrants who pay taxes |

| Earned | extra burdens at work, including COVID-19 exposures, that were not acknowledged by employers; lack of compensation for sick leave | feeling like their workplace contributions were not acknowledged; lack of self-esteem from not working; forced to quit their jobs because of lack of workplace protections |

| Remediated | stressful and intimidating work conditions; losing work without notice | excluded from the rehiring process |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamanis, T.J.; Rao, S.; Reichert, A.J.; Haws, R.; Morrissey, T.; Suarez, A. Dignity of Work and at Work: The Relationship between Workplace Dignity and Health among Latino Immigrants during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 855. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070855

Yamanis TJ, Rao S, Reichert AJ, Haws R, Morrissey T, Suarez A. Dignity of Work and at Work: The Relationship between Workplace Dignity and Health among Latino Immigrants during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(7):855. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070855

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamanis, Thespina J., Samhita Rao, Alexandra J. Reichert, Rachel Haws, Taryn Morrissey, and Angela Suarez. 2024. "Dignity of Work and at Work: The Relationship between Workplace Dignity and Health among Latino Immigrants during the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 7: 855. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070855

APA StyleYamanis, T. J., Rao, S., Reichert, A. J., Haws, R., Morrissey, T., & Suarez, A. (2024). Dignity of Work and at Work: The Relationship between Workplace Dignity and Health among Latino Immigrants during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(7), 855. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070855