Dynamic Deconstructive Psychotherapy for Suicidal Adolescents: Effectiveness of Routine Care in an Outpatient Clinic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Treatments

2.4. Measures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Primary Outcome

3.2. Secondary Outcomes

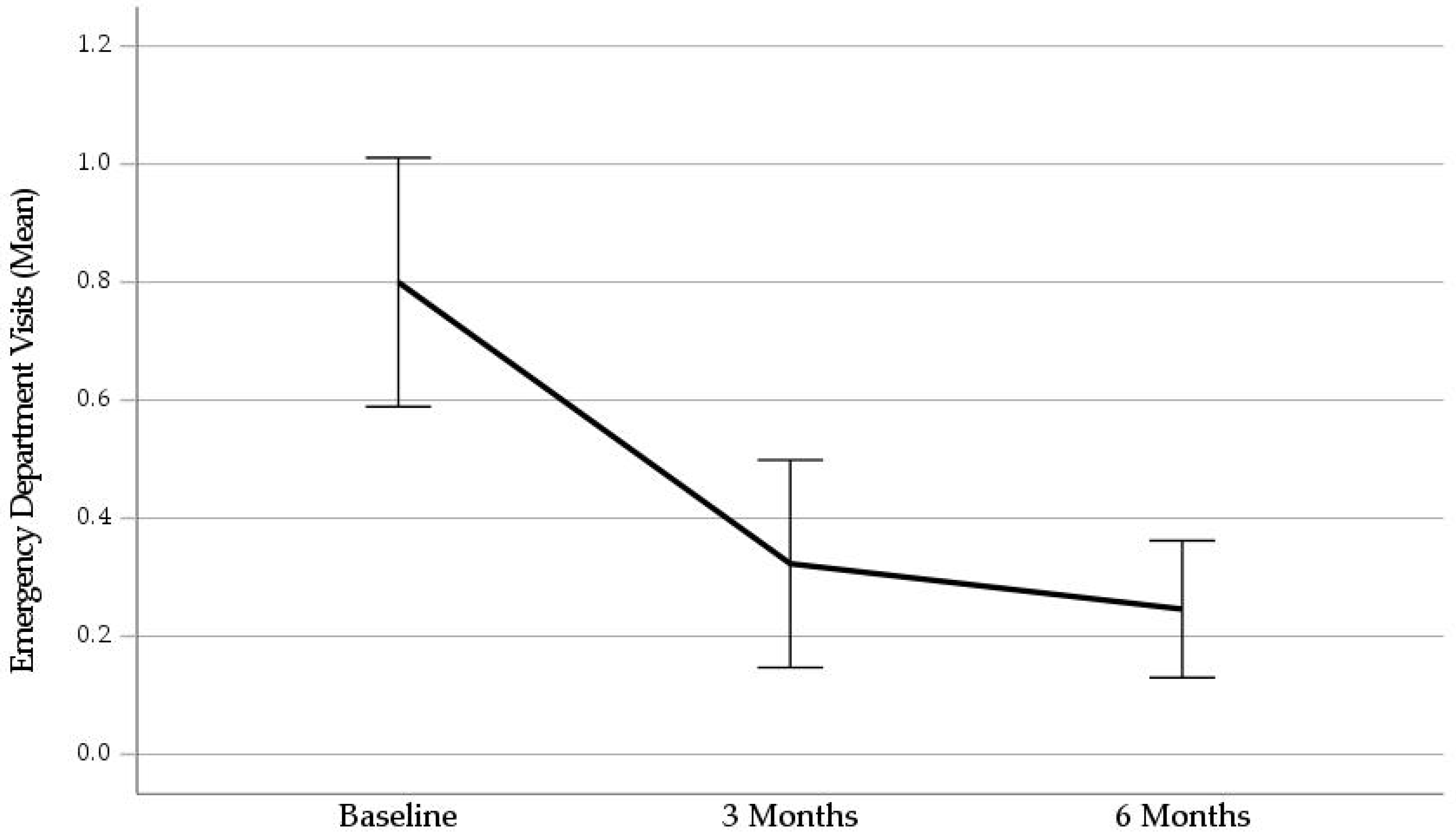

3.3. Utilization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ivey-Stephenson, A.Z.; Demissie, Z.; Crosby, A.E.; Stone, D.M.; Gaylor, E.; Wilkins, N.; Lowry, R.; Brown, M. Suicidal ideation and behaviors among high school students—Youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Suppl. 2020, 69, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Leading Causes of Death Visualization Tool. Available online: https://wisqars.cdc.gov/data/lcd/home (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- World Health Organization. Suicide Worldwide in 2019: Global Health Estimates. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026643 (accessed on 26 January 2023).

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report 2011–2021. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/YRBS_Data-Summary-Trends_Report2023_508.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Arakelyan, M.; Freyleue, S.; Avula, D.; McLaren, J.L.; O’Malley, A.J.; Leyenaar, J.K. Pediatric mental health hospitalizations at acute care hospitals in the US, 2009–2019. JAMA 2023, 329, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bommersbach, T.J.; McKean, A.J.; Olfson, M.; Rhee, T.G. National Trends in Mental Health–Related Emergency Department Visits Among Youth, 2011–2020. JAMA 2023, 329, 1469–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, L.M. Surgeon General Calls for Action to Address Youth Mental Health Crisis. Psychiatr. News 2022, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothgassner, O.D.; Goreis, A.; Robinson, K.; Huscsava, M.M.; Schmahl, C.; Plener, P.L. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescent self-harm and suicidal ideation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 1057–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, T.R.; Merranko, J.; Rode, N.; Sylvester, R.; Hotkowski, N.; Fersch-Podrat, R.; Hafeman, D.M.; Diler, R.; Sakolsky, D.; Birmaher, B.; et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with bipolar disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossouw, T.I.; Fonagy, P. Mentalization-based treatment for self-harm in adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2012, 51, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito-Smythers, C.; Spirito, A.; Kahler, C.W.; Hunt, J.; Monti, P. Treatment of co-occurring substance abuse and suicidality among adolescents: A randomized trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 79, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahji, A.; Pierce, M.; Wong, J.; Roberge, J.N.; Ortega, I.; Patten, S. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of psychotherapies for self-harm and suicidal behavior among children and adolescents: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e216614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, E.; Bo, S.; Jørgensen, M.S.; Gondan, M.; Poulsen, S.; Storebø, O.J.; Andersen, C.F.; Folmo, E.; Sharp, C.; Simonsen, E.; et al. Mentalization-based treatment in groups for adolescents with borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, R.J.; Remen, A.L. A manual-based psychodynamic therapy for treatment-resistant borderline personality disorder. Psychotherapy 2008, 45, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, R.J.; Chlebowski, S.; Kang, D.; Remen, A.L.; Soderberg, M.G.; Stepkovitch, J.; Virk, S. A controlled trial of psychodynamic psychotherapy for co-occurring borderline personality disorder and alcohol use disorder. Psychotherapy 2008, 45, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, R.J.; Delucia-Deranja, E.; Mogle, J.A. Dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy versus optimized community care for borderline personality disorder co-occurring with alcohol use disorders: A 30-month follow-up. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2010, 198, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majdara, E.; Rahimian-Boogar, I.; Talepasand, S.; Gregory, R.J. Dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy in Iran: A randomized controlled trial with follow-up for borderline personality disorder. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2021, 38, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, R.J.; Sachdeva, S. Naturalistic outcomes of evidence-based therapies for borderline personality disorder at a medical university clinic. Am. J. Psychother. 2016, 70, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.G.; Sperry, S.D.; Shields, R.J.; Gregory, R.J. A novel recovery-based suicide prevention program in upstate New York. Psychiatr. Serv. 2022, 73, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, K.; Brown, G.K.; Stanley, B.; Brent, D.A.; Yershova, K.V.; Oquendo, M.A.; Currier, G.W.; Melvin, G.A.; Greenhill, L.; Shen, S.; et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, M.D.; Eisenberger, N.I.; Crockett, M.J.; Tom, S.M.; Pfeifer, J.H.; Way, B.M. Putting feelings into words: Affect labeling disrupts amygdala activity in response to affective stimuli. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durkheim, E. A Study in Sociology; Routledge and Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden, K.A.; Witte, T.K.; Cukrowicz, K.C.; Braithwaite, S.R.; Selby, E.A.; Joiner, T.E. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, I.; Barry, C.N.; Cooper, S.A.; Kasprow, W.J.; Hoff, R.A. Use of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) in a large sample of Veterans receiving mental health services in the Veterans Health Administration. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2020, 50, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, G.E.; Rutter, C.M.; Peterson, D.; Oliver, M.; Whiteside, U.; Operskalski, B.; Ludman, E.J. Does response on the PHQ-9 depression questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death? Psychiatr. Serv. 2013, 64, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, K.H.; Sheehan, D.V. Assessing treatment effects in clinical trials with the discan metric of the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2008, 23, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raes, F.; Pommier, E.; Neff, K.D.; Van Gucht, D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2011, 18, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trautman, P.D.; Stewart, N.; Morishima, A. Are adolescent suicide attempters noncompliant with outpatient care? J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1993, 32, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCauley, E.; Berk, M.S.; Asarnow, J.R.; Adrian, M.; Cohen, J.; Korslund, K.; Avina, C.; Hughes, J.; Harned, M.; Gallop, R.; et al. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents at high risk for suicide a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, G.J.; Rodean, J.; Zima, B.T.; Doupnik, S.K.; Zagel, A.L.; Bergmann, K.R.; Hoffmann, J.A.; Neuman, M.I. Trends in pediatric emergency department visits for mental health conditions and disposition by presence of a psychiatric unit. Acad. Pediatr. 2019, 19, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yard, E.; Radhakrishnan, L.; Ballesteros, M.F.; Sheppard, M.; Gates, A.; Stein, Z.; Hartnett, K.; Kite-Powell, A.; Rodgers, L.; Adjemian, J.; et al. Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12–25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January 2019–May 2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyz, E.K.; Berona, J.; King, C.A. Rehospitalization of suicidal adolescents in relation to course of suicidal ideation and future suicide attempts. Psychiatr. Serv. 2016, 67, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Beurs, D. Network analysis: A novel approach to understand suicidal behaviour. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | n | % |

| Age | ||

| 13–15 | 26 | 40 |

| 16 | 20 | 31 |

| 17 | 19 | 29 |

| Sex Assigned at Birth | ||

| Male | 10 | 15 |

| Female | 55 | 85 |

| Gender Identity | ||

| Cisgender | 44 | 68 |

| Transgender | 6 | 9 |

| Non-Binary | 15 | 23 |

| Race | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 | 2 |

| Asian | 2 | 3 |

| Black or African American | 1 | 2 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 |

| White | 61 | 94 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 | 5 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 62 | 95 |

| Insurance | ||

| Government Insurance | 26 | 40 |

| Private Insurance | 39 | 60 |

| Participants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Diagnoses | n | % |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 7 | 11 |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 2 | 3 |

| Other neurodevelopmental disorders | 1 | 2 |

| Major depressive disorder | 61 | 94 |

| Persistent depressive disorder | 4 | 6 |

| Other mood disorders | 3 | 5 |

| Panic disorder | 4 | 6 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 31 | 48 |

| Other anxiety disorders | 4 | 6 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 8 | 12 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 35 | 54 |

| Dissociative identity disorder | 1 | 2 |

| Anorexia nervosa | 10 | 15 |

| Bulimia nervosa | 7 | 11 |

| Binge-eating disorder | 3 | 5 |

| Other feeding or eating disorders | 3 | 5 |

| Gender dysphoria | 7 | 11 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 5 | 8 |

| Cannabis use disorder | 17 | 26 |

| Nicotine use disorder | 4 | 6 |

| Borderline personality disorder | 50 | 77 |

| Measure | Baseline M (SD) | 3 Months M (SD) | 6 Months M (SD) | Z | p | r c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-SSRS Suicide Ideation | 3.26 (1.06) | 2.25 (1.41) | 1.74 (1.62) | −5.52 | <0.001 | 0.68 |

| C-SSRS Suicide Attempts | 1.38 (2.34) | 0.46 (1.04) | 0.26 (0.91) | −3.64 | <0.001 | 0.45 |

| PHQ-9 Depression | 19.86 (4.84) | 16.98 (5.17) | 14.12 (6.39) | −5.69 | <0.001 | 0.71 |

| PHQ-9 Suicide Ideation | 2.11 (1.00) | 1.48 (1.04) | 1.00 (1.06) | −5.67 | <0.001 | 0.70 |

| Self-Harm Behaviors | 5.51 (7.40) | 1.52 (2.12) | 0.86 (1.89) | −5.23 | <0.001 | 0.65 |

| GAD-7 Anxiety | 15.71 (4.61) | 13.98 (4.56) | 11.79 (5.24) | −4.92 | <0.001 | 0.61 |

| Sheehan Disability Scale | 6.97 (1.77) | 6.63 (1.84) | 5.37 (2.72) | −3.93 | <0.001 | 0.49 |

| Self-Compassion Scale | 2.07 (0.54) | 2.40 (0.65) | 2.68 (0.65) | −5.96 | <0.001 | 0.74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shields, R.J.; Helfrich, J.P.; Gregory, R.J. Dynamic Deconstructive Psychotherapy for Suicidal Adolescents: Effectiveness of Routine Care in an Outpatient Clinic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 929. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070929

Shields RJ, Helfrich JP, Gregory RJ. Dynamic Deconstructive Psychotherapy for Suicidal Adolescents: Effectiveness of Routine Care in an Outpatient Clinic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(7):929. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070929

Chicago/Turabian StyleShields, Rebecca J., Jessica P. Helfrich, and Robert J. Gregory. 2024. "Dynamic Deconstructive Psychotherapy for Suicidal Adolescents: Effectiveness of Routine Care in an Outpatient Clinic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 7: 929. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070929

APA StyleShields, R. J., Helfrich, J. P., & Gregory, R. J. (2024). Dynamic Deconstructive Psychotherapy for Suicidal Adolescents: Effectiveness of Routine Care in an Outpatient Clinic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(7), 929. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070929