Abstract

Introduction: Public safety personnel (PSP) experience operational stress injuries (OSIs), which can put them at increased risk of experiencing mental health and functional challenges. Such challenges can result in PSP needing to take time away from the workplace. An unsuccessful workplace reintegration process may contribute to further personal challenges for PSP and their families as well as staffing shortages that adversely affect PSP organizations. The Canadian Workplace Reintegration Program (RP) has seen a global scale and spread in recent years. However, there remains a lack of evidence-based literature on this topic and the RP specifically. The current qualitative study was designed to explore the perspectives of PSP who had engaged in a Workplace RP due to experiencing a potentially psychologically injurious event or OSI. Methods: A qualitative thematic analysis analyzed interview data from 26 PSP who completed the RP. The researchers identified five themes: (1) the impact of stigma on service engagement; (2) the importance of short-term critical incident (STCI) program; (3) strengths of RP; (4) barriers and areas of improvement for the RP; and (5) support outside the RP. Discussion: Preliminary results were favorable, but further research is needed to address the effectiveness, efficacy, and utility of the RP. Conclusion: By addressing workplace reintegration through innovation and research, future initiatives and RP iterations can provide the best possible service and support to PSP and their communities.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Public safety personnel (PSP) experience operational, personal, and organizational stressors that put them at heightened risk of developing mental health challenges compared to civilian populations [1]. A broad and evolving “term to describe the people who ensure the safety and security of the public” [2], PSP includes “border services officers, serving Canadian Armed Forces members and Veterans, correctional service and parole officers, firefighters (career and volunteer), Indigenous emergency managers, operational intelligence personnel, paramedics, police officers, public safety communicators (e.g., 911 dispatchers), and search and rescue personnel” [3]. One Canadian study found that 36.7% of municipal police, 34.1% of firefighters, 50.2% of Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), and 49.1% of paramedical staff surveyed screened positive for one or more mental health conditions including but not limited to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [1].

Operational stress injuries (OSIs) is a term “often used by PSP to describe mental health problems that may result from performing their assigned duties” [3]. OSIs are not listed as a diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) [4]. The term can encompass a range of mental health conditions, including PTSD, major depressive disorder, and various mood-, anxiety-, trauma-, and substance use-related disorders [3] as well as moral injury and burnout. OSI symptoms may result in diminished cognitive functioning, increased social isolation, difficulty with interpersonal relationships, and increased workplace absenteeism [5,6]. Functional impairments from OSIs contribute to challenges with returning to work in a present, meaningful, and engaged manner [7]. An unsuccessful return-to-work process can exacerbate financial and mental health distress for the PSP member and their family as well as contribute to staffing shortages that can have adverse consequences for PSP organizations and the communities they serve. Although the economic burden of OSIs among Canadian PSP is unknown [8], estimates of productivity losses for mental health disorders among the Canadian population due to factors like absenteeism range from 16.6 to 21 billion annually [9,10,11].

Despite the importance of successful return-to-work experiences and processes, the published literature on workplace reintegration after clinical rehabilitation to address OSIs is limited. Initiatives to address gaps between clinical care and functional workplace tasks are beginning to emerge through grassroots efforts by various PSP organizations. Many PSP organizations have recognized peer support as a component of an overall work reintegration strategy that may help PSP return to work following injury. Formalized peer support refers to a variety of mental health supports and resources implemented via programs or services and offered by a peer who provides social, emotional, spiritual, and instrumental support to promote well-being and recovery [3,12]. Historically, PSP peer support has been based on a shared lived experience, such as similar employment or exposure to potentially psychologically injurious events (PPIEs) [3,13]. Based on a review of the literature on initiatives designed to support PSP in their workplace reintegration after incidents, Sutton and Polaschek (2022) [14] identified the incorporation of peer support, focusing on stress and well-being outcomes and education, across all types of studies but noted “a dearth of research into the influence of critical incident interventions on work performance, attitudes or experiences” (pp. 732). In formal peer-support initiatives, the knowledge and expertise possessed by the peer supporter through their lived experience is often supplemented with additional training and mental health knowledge [3,15,16].

Peer-support programs are difficult to evaluate in an implementation science or research context. This is because there does not exist standardization among these programs, making examination of the safety, effectiveness, efficacy, and impact of such initiatives challenging [16]. The training and experience of peer supporters, level of formalization and structure, accessibility (i.e., virtual versus in-person), and the mandates or goals of peer-support initiatives vary widely across organizations, professions, and jurisdictions [10,17,18]. To improve the evaluation of the effectiveness of peer-support programs and crisis-focused psychological intervention programs, the current literature recommends further standardization of research and peer-support programs, rigorous methodological research designs, and research engagement of independent, qualified, and established researchers [10,17,18].

1.2. A Peer-Led Workplace Reintegration Program

The Edmonton Police Service (EPS) identified a need to assist police officers who were off work following some PPIE exposures designated as “critical incidents”. Operational definitions of critical incidents can vary among PSP organizations and professions but often include officer-involved shootings and events where serious injury or death of an individual has occurred. Workplace reintegration efforts were introduced in 2009 as a response to this issue, by providing officers with a peer-led program to guide them through their critical incidents and regain confidence in operational skills [19]. The EPS Reintegration Program (RP) has evolved and spread to several other PSP organizations and professions across Canada, the United States, and New Zealand [7,20]. RPs may include elements specific to each PSP organization and profession, but the goal of the program remains to assist PSP with returning to work as soon as possible following a PPIE, illness, or injury while diminishing the potential for long-term psychological injury [19].

The RP incorporates short-term critical incident (STCI) and long-term RP streams [19]. Detailed descriptions of the RP have previously been published in detail [20]. The STCI stream is a proactive psychological program [10] offered to PSP immediately after a critical incident to assist with rebuilding confidence in skills and providing support in hopes to mitigate the potential future impact of an OSI on workplace reintegration and engagement. This stream may also incorporate mandatory time away from work and engage clearance and short-term intervention by a medical or mental health professional prior to full return to duty. Both streams of the RP include elements of relationship building, reorientation to equipment related to their role, skill building, and exposure to common workplace scenarios. PSP enrolled in the RP are guided by a trained peer RP facilitator who assists with exposure to unique stressors that the PSP may experience in their role [19]. Peer support offered by RPs is complementary to clinical interventions but outside the scope of what officers receive from their healthcare professionals [19]. Peer-support duties within the RP expand beyond the scope of basic peer support and into a formalized program of meaningful assistance, for which the RP facilitators receive specialized training [15,16]. The previous literature on RPs has emphasized the importance of having the right fit for peers in the role as facilitators, including a positive reputation and respect by peers within the organization, to facilitate buy-in and reduce stigma [7,16].

Research on initiatives targeting PSP after PPIEs similar to the RP have recently been published. A Canadian literature review reported limited evidence supporting post-exposure peer support and crisis-focused psychological interventions, which may include critical-incident stress debriefing, stress management, peer support, psychological first aid, and trauma risk management in isolation or combination, in mitigating PTSIs among PSP [16]. A literature review from New Zealand noted promising preliminary findings for peer-led tertiary interventions, indicating that further evaluation and research of these types of programs, including the RP, is warranted [14]. Published studies on the RP itself are limited but include work describing program stakeholder perspectives [7], introducing internally collected program statistics [19], and clarifying the outcomes of the RP facilitator training [15,16]. Research addressing whether this specific RP is effective, efficacious, or safe from an evidence-based perspective is yet to be completed. Initiatives such as the RP must be evaluated to clarify current effectiveness, support continuous improvement, and protect investment returns.

1.3. Research Question and Study Purpose

This qualitative study aimed to explore experiences and perspectives of PSPs who had engaged in the workplace RP designed by EPS after experiencing a PPIE or an OSI. This study aimed to address the following research questions: (1) What are the experiences of PSP engaged in the RP after a PPIE or OSI? (2) Do PSP engaged in the RP perceive it as effective in assisting in their return-to-work process? The study results can provide valuable information on participant perspectives regarding the impact of the RP on PSP returning to duty. Based on previous research, PSP participants were expected to view the RP as a favorable element of the workplace reintegration process [7,20].

2. Materials and Methods

This qualitative study used an overarching community-engaged and pragmatic research approach [21,22] with a thematic analysis to better understand the perspectives of PSP regarding the workplace RP within Alberta, Canada. Ethical approval was received from the Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta (Pro00118357).

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

Potential participants for the current study included PSP who had participated in an RP program within their organization. Participating organizations included EPS, Alberta Health Services Emergency Medical Services, St. Albert Fire Services, and the RCMP. Study participants were recruited through purposeful sampling. Potential participants were asked by their RP facilitator at their initial contact if they would be interested in participating in the study. Study team members contacted potential participants who consented to be contacted. After screening for eligibility, willing PSP provided written consent to participate in the study. PSP were eligible if they had taken time off work due to experiencing a PPIE identified as a critical incident or an OSI. As a result, the participants had engaged or were about to engage in the STCI or long-term stream of the workplace RP within their respective organizations. Participants were not eligible if they had engaged in the RP due to time off of work for a medical illness, musculoskeletal injury, or maternity leave that did not directly include a PPIE or psychological challenges related to the workplace. Recruitment took place from May 2022 to September 2023.

2.2. Data Collection

Quantitative and qualitative data were collected between May 2022 and December 2023. Consent and demographic questionnaires were administered via REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), which is a secure, web-based software platform [23]. The research team designed a deductive semi-structured interview script based on the research questions and after consultation with key partners of the RP. Steps used to develop the guide included (1) considering which event(s) illustrate phenomena of interest, (2) ordering questions to optimize flow, and (3) refining the schedule through a series of review and piloting [24]. Based on the iterative process and in line with suggested qualitative research methodology for the development of interview scripts for thematic analysis [25], six topic areas were included in the interview: (1) events that led to being off work; (2) level and type of support; (3) steps in the reintegration process; (4) relationships with key partners and organizations; (5) perceived strengths, facilitators, and barriers of the RP; and (6) perceived effectiveness and efficacy of the RP (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of Questions in the Semi-Structured Interview Guide.

Participants were asked to participate in an interview at three months post initiation of their involvement with either the STCI or long-term stream of the RP. Individual interviews (n = 26) lasting approximately 60 min were conducted and recorded over a secure Zoom video conferencing link according to the existing literature and guidelines for qualitative data collection [26]. Data collection continued until information power was reached [25]. Information power considers study focus, sample specificity, established theory, quality of dialogue, and analysis strategy, which would ideally also correlate with data saturation [27].

2.3. Data Analyses

Quantitative data were captured and analyzed descriptively using Microsoft Excel software. Qualitative data in the form of audio or video-recorded interviews were professionally transcribed. Data were anonymized at this step by assigning a participant number to each transcript. The transcripts were then thematically analyzed deductively and inductively following an iterative process [26]. Initial codes were developed through an inductive process by identifying both manifest and latent themes that presented in the data. The semi-structured interview script was deductive and included specific questions about the RP. Manifest content emerged, including content related to logistic aspects of the RP, that was analyzed at face value.

There were two researchers (S.S. and E.O.) who independently conducted open coding of the transcribed data for each interview, after which arms-length researchers (C.J. and S.B.-P.) reviewed and provided feedback on the codes. Axial coding and the development of preliminary themes followed, with disagreements being resolved through discussion.

Trustworthiness [27] was considered throughout and facilitated through the clear problem statement, development of a relevant research question, and an a priori research method. Appropriate and thoughtful qualitative approaches were used to address the research question with flexibility [28,29,30]. Additionally, critical reflexivity was considered throughout data analyses, and discussions regarding researcher positionality, perspectives, relationships, and biases were engaged at multiple points throughout the study [28].

Once the final themes were determined, key quotes were isolated to illustrate the themes, and the final presentation of the thematic analysis was prepared. The Standard for Reporting Qualitative Research was used to guide the reporting process [31].

2.4. Triangulation

The overarching mixed-methods research study used method and data triangulation of multiple qualitative and quantitative approaches and sources of which have [7] and will be reported in future peer-reviewed manuscripts. A concurrent parallel approach following a data transformation model was used in this larger initiative’s final data analysis process to converge the data for comparing and contrasting the quantitative results with qualitative findings [32].

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

The demographic details of study participants (n = 26) are presented in Table 2 below. Study participants were an average age of 35.08 (SD = 7.95) years and belonged to one of Alberta’s four participating PSP organizations. Levels of experience within their respective fields varied, with the average years in their profession being 9.85 (SD = 6.45).

Table 2.

Sample Demographics.

3.2. Qualitative Thematic Analysis Results

The thematic analysis revealed a breadth of information on the experience of the participants who engaged in the RP. The participants experienced numerous PPIEs and other workplace stressors throughout their career, all of which was conveyed through their stories and anecdotes. Participants were acutely aware of the potential for greater mental unwellness with increased exposures to PPIEs. Some participants had previously engaged in the RP after past PPIEs. Other participants had not had the opportunity for participation in an RP until present, as their past PPIEs had occurred before the installation of the RP within their organization. A few participants noted they had participated in the RP multiple times to date. Overall, the participants generally perceived the RP as positively impacting their workplace reintegration.

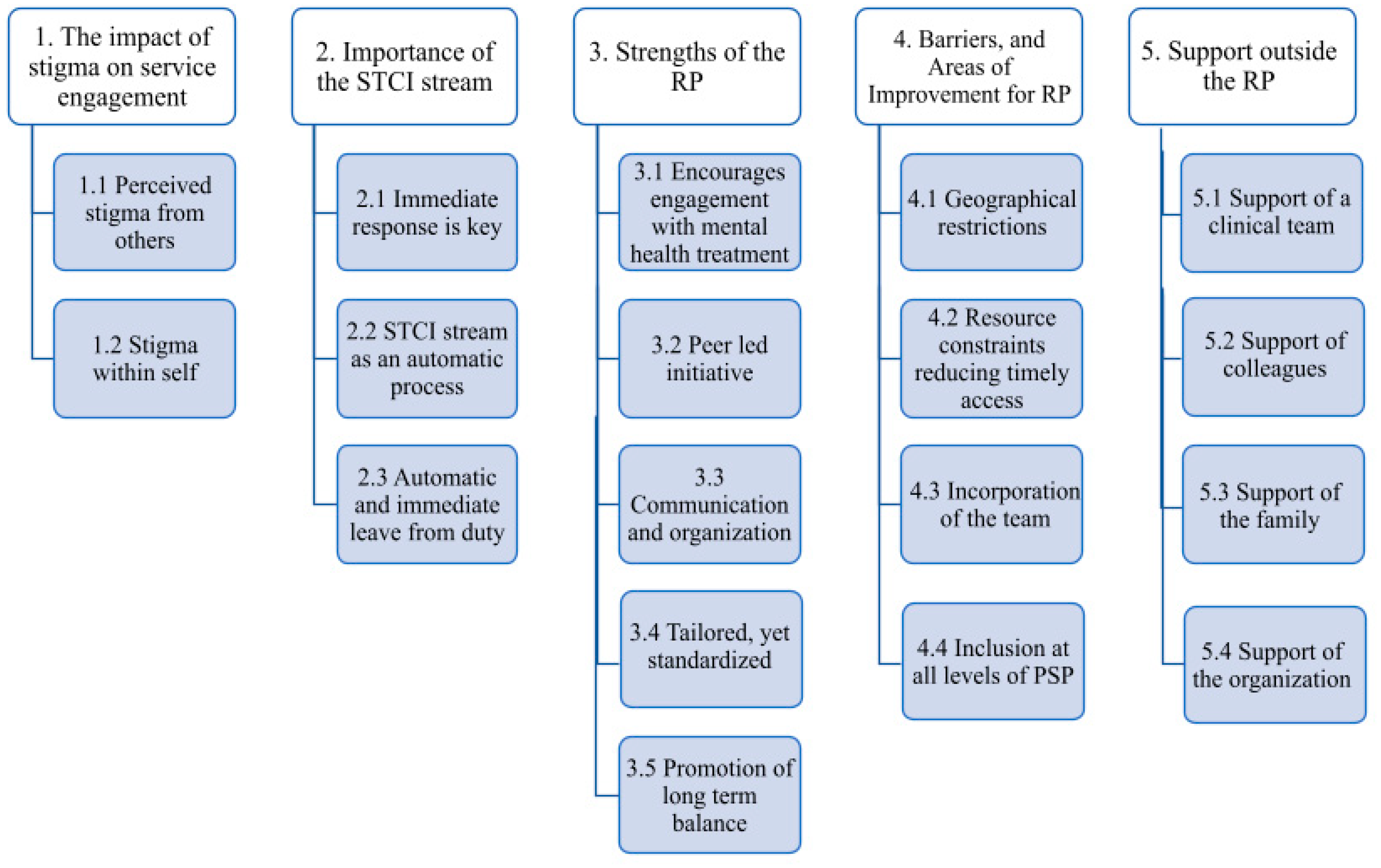

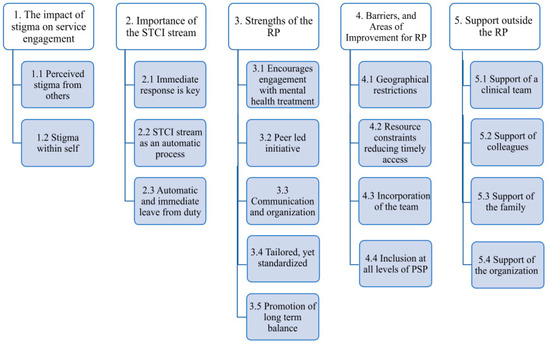

The thematic analysis yielded five main themes: (1) the impact of stigma on service engagement; (2) importance of the STCI program; (3) strengths of RP; (4) barriers and areas of improvement for the RP; and (5) support outside the RP (Figure 1). The themes are summarized below, supported by detailed descriptions and supporting quotes.

Figure 1.

Qualitative Analysis Results.

3.2.1. The Impact of Stigma on Service Engagement

Stigma was identified by participants as an important factor that affected decision-making regarding taking time off work, engaging in mental health services, and participating in other formal and informal peer support, including the RP. Participants reported experiencing stigma from colleagues and the organization in the workplace and within PSP themselves due to internalized pressure to perform and a strong professional identity. Stigma contributed to feelings of shame or guilt when affected by an OSI. Stigma from others or self was noted to potentially contribute to PSP staying in the workplace longer than is indicated with an OSI, avoiding seeking clinical treatment, and potentially attempting to navigate workplace reintegration without a formalized program such as the RP.

Despite stigma remaining a factor that may affect PSP engagement in services designed to assist them, many participants noted that mental health stigma has decreased and continues to decrease in the workplace and PSP professions. Improvements were largely attributed to numerous initiatives within PSP organizations and their professions designed to increase mental health knowledge, normalize discussions about mental health, improve recognition of the signs and symptoms of OSI, and encourage seeking help when needed (Table 3).

Table 3.

The Impact of Stigma on Service Engagement.

3.2.2. The Importance of the STCI Stream

Participants who participated in the STCI stream of the RP endorsed its importance to the work RP after experiencing a PPIE in the workplace. Implementing the STCI stream was described as providing a prompt and supportive response for PSP to get directions on reintegration, peer support, and mandatory time away from work. Many participants felt that integrating the STCI stream into mandatory processes was a strength of the RP. The STCI stream was found to be a helpful process for those who engaged in it, positively impacting their personal and professional lives. Some participants noted that they were likely to voluntarily engage in the STCI stream as needed in the future.

It is important to note that not all of the PSP organizations had an STCI stream. A few participants reported that they wished to advocate for PSP organizations whose RPs did not include a STCI stream because they believed so strongly in the benefits of this approach and process (Table 4).

Table 4.

The Importance of the STCI Stream of the RP.

3.2.3. Strengths of the RP

The participants identified perceived strengths of both the STCI and long-term streams of the RP. These included (a) encouraging clinical mental health engagement; (b) peer involvement; (c) communication and organization by the RP team; (d) a standardized program with the flexibility to adjust to individual needs; and (e) promotion of long-term health and wellness. The RP implementation created a community and minimized the impacts of social isolation. Participants conveyed that the RP assisted in their workplace reintegration and was a welcomed component of their recovery journey (Table 5).

Table 5.

Strengths of the RP.

3.2.4. Barriers and Areas of Improvement for RP

The barriers and areas of improvement cited by participants varied among PSP organizations, as each had its own unique jurisdictions, demands, resourcing, and slight variations in program design. Many participants across the PSP organizations identified geographical restrictions as a barrier to participation in the RP. Some also noted that factors such as resourcing restricted timely access to the RP after a critical incident. Additionally, some participants conveyed that incorporation of their team members would be a benefit to the reintegration process. Participants also reported that the RP is viewed by others within the organizations as an initiative for those on the front lines of PSP work, and PSP in more administrative or supervisory roles may feel less welcome. Refer to Table 6 for further detail.

Table 6.

Barriers and Areas of Improvement for RP.

3.2.5. Support outside the RP

The RP was described as a source of support during the return-to-work process; nevertheless, participants reported other support as important for their workplace reintegration, such as clinical support from a healthcare team through formal OSI treatments. Additionally, support, or a lack of it, from colleagues, family, the profession, and the organization were identified as potentially affecting the success of the process by either adversely contributing to or mitigating stressors during workplace reintegration (Table 7).

Table 7.

Support Outside the RP.

4. Discussion

The current qualitative study was designed to explore the experiences and perspectives of PSP who had engaged in a workplace RP due to experiencing a PPIE, identified as a critical incident, or OSI. The current study is the first to address the perceived effectiveness and utility of a specific workplace RP, demonstrating favorable results. The results of this study successfully provided insight into the following research questions: (1) What are the experiences of PSP engaged in the RP after a PPIE or OSI? (2) Do PSP engaged in the RP perceive it as effective in assisting in their return-to-work process? Overall, PSP felt favourably towards the RP and reported that they found it was a valuable component of their return-to-work journey after a PPIE or OSI.

Most participants identified as men (77%), which is consistent with the gender estimates among policing professions in Canada [33]. Many participants were in their early to mid-career (n = 22), and over half (n = 15) had participated in the STCI stream of the RP opposed to the long-term stream (n = 11). Having entered the program immediately after a PPIE may be, in part, why most of the participants had already returned to work at full capacity. As data collection commenced at three months post entry into the RP, it remains possible that some participants may still be affected by an OSI in the future.

Through the qualitative thematic analysis, five themes were developed. Of note, the themes shared some similarities to the recent qualitative literature regarding the return to duty of Canadian PSP as well as discussions of peer support and the current state of programs and initiatives that aim to mitigate the effects of PPIEs on PSP.

Stigma remains an influential factor in the decision making of PSP regarding seeking mental health support, taking time off from work, and engaging formal and informal services [32], which may include the RP. Participants noted internal and perceived external stigma as a barrier to acknowledging OSIs and seeking treatment, which is consistent with the recent literature [34,35,36,37]. An overall reduction in stigma and increase in mental health literacy is being observed among PSP populations [14,15,16,35], which the data from this study corroborated. Reducing stigma, therefore, may facilitate workplace reintegration [35,37].

The STCI stream of the RP is a peer-led, tertiary intervention [14] that is used by some of the PSP organizations after a PPIE exposure that meets the organization’s criteria for being a critical incident. The current results suggested participants felt the STCI was a particularly important part of the RP. Important elements included automatic participation post PPIE, mandated leave from duty after this event, and the immediate engagement of the RP facilitators. Further research is warranted on the impact of the mandatory nature of workplace reintegration initiatives and time off work after exposure to PPIEs.

Participants reported several strengths of the RP. First, the RP reportedly encouraged participants to engage with mental health treatment and was often responsible for providing resources for the PSP member to connect with healthcare professionals. Second, participants identified the peer-led aspect as an integral strength of the workplace reintegration process. This result is consistent with the previous literature establishing the benefits of both formal and informal peer supports related to reducing mental health stigma [36,37,38,39,40] and facilitating PSP workplace reintegration [7,14,35]. Third, the ability to accommodate and tailor the RP approach within the standard format was a program strength. Pacing exposure activities and graduating the return to duties in a way that fostered choice and control within the individual was paramount to fostering trust with the RP facilitator as well as others within the PSP organization. An individualized and tailored approach to workplace reintegration has been recommended in the literature for civilian populations and is also emerging in the literature specific to PSP [16,35,37].

The importance of high-quality communication strategies as part of the reintegration process was emphasized as a contingency for the satisfaction and success of returning to work after illness or injury in multiple sectors. This was also an evident theme among study participants, which is consistent with the literature regarding workplace reintegration of PSP [16,35,37,41]. Workplace reintegration is a complex process that requires coordination of multiple parties, necessitating timely, clear, and genuine communication between the individual and others, with varying privacy and confidentiality requirements [39,41]. This need may be amplified when PSP are experiencing mental health symptoms or acute stress due to a critical incident [41]. Most participants felt the RP enhanced communication throughout their involvement.

Lastly, participants appreciated the focus on the balance of their professional and personal lives and emphasis on sustained wellness. Other studies of PSP engaged in workplace reintegration also cited aspirations of improving lifestyle behaviours, finding joy, and managing stress over the long term [35].

Barriers and areas of improvement related to the RP were also noted in the findings. Geographical restrictions and difficulties with adequate resourcing to meet demands were noted by participants, which is consistent with previous publications [7]. The incorporation of the team into the RP as well as encouraging a safe and welcome program for all ranks, including leadership, were ideas that emerged in the data as potentially strengthening the RP.

Support from outside the RP was observed as an important element of a successful workplace reintegration after a critical incident or OSI. Healthcare providers were noted as a support used by many of the participants. A recent Canadian study found that during the workplace reintegration process, PSP were most likely to access psychologists, occupational therapists [42], and family physicians when engaged with a workers compensation organization [35]. This study also noted that, due to the nature of PSP careers, it is advantageous for healthcare providers to be informed of the different roles and traumatic events that various PSP experience to improve engagement and outcomes with experienced healthcare providers being cited as a facilitator for return to work [35].

Colleagues within the profession and organization were noted to play an important role through informal peer support. Strong co-worker and supervisor support were observed as positive organizational factors that facilitate better mental health among PSP organizations [40]. Colleagues have been highlighted for the important part they play in the return-to-work processes [39,43], and it has been suggested that a more formalized role may facilitate improved reintegration experiences [44].

Family support was identified as an important factor in workplace reintegration, consistent with other literature [35,45]. Some PSP felt comfortable reaching out to their spouses or other family for support when needed. On the contrary, some participants did not feel comfortable speaking to their family, as they felt they would not understand the nuances and context of PSP work or may be burdened by the challenging nature of the work.

The importance of feeling supported by the PSP organization as a whole was important to participants. The RP was important for facilitating trust and connection with the organization. Connection with the workplace was previously noted as a facilitator of a more successful workplace reintegration for PSP [46,47]. Numerous publications have emphasized the importance of trust and buy-in with the organization in reintegration efforts for PSP [6,7,37,40,41].

4.1. Practice Recommendations

First, the continued facilitation of strong communication between the RP, individual PSP, and partner department, organizations, and healthcare teams appears particularly important [7]. Organizations using an RP without the STCI stream should consider trialing this piece of the RP. In the organizational context, RP teams should assess whether the intra-organizational messaging and marketing of the program fosters trust and feelings of inclusion for all levels of leadership, including PSP in supervisory and administrative positions.

RP delivery and training of RP facilitators should remain standardized to support implementation consistency across jurisdictions, professions, and organizations, thereby facilitating meaningful evaluations of effectiveness. Research and evaluation tools across RPs should also remain consistent. If research results regarding the RP are favourable, the use of effective implementation science and program evaluation approaches would best facilitate sustainable spread and scale with fidelity and quality control [16]. The use of validated pre–post surveys or outcome measures for PSP going through the RP would also provide useful and detailed information regarding the impact of the RP.

4.2. Research Recommendations

Research conducted by qualified arms-length research teams external to the PSP organizations is recommended for mitigation of bias and conflict of interest with programs like the RP and its partners [17]. Future research should incorporate constructs and conditions that may correlate with success in sustained return to work, such as measures of absenteeism, presenteeism, organizational injustice, work function, work performance, and perceived stigma as well as mental health knowledge and attitudes [8,15,18]. Studies on the organizational and cultural impact of the RP and a cost–benefit analysis would also be advantageous to assist in providing the best and most appropriate programming possible for PSP [8,9]. Studies that employ larger samples and quantitative methods are also needed to further address the question of efficacy, effectiveness, and utility of the program on constructs of return to work [17,18]. Both randomized and non-randomized studies are needed to inform further program modalities and delivery methods for PSP, which may include virtual means of service delivery [17,18]. Favourable research results would potentially pave the way for more widespread program adoption and integration that ensures risk management strategies and the maintenance of program fidelity [7,17].

The RP may also be a promising initiative to trial in other sectors where there is increased exposure to PPIEs, such as in healthcare settings [48]. Further research and exploration are still needed prior to the implementation, spread, and scale of the RP to other industries.

4.3. Limitations of Study

Limitations associated with the study include a convenience sample that drew on pre-existing relationships with a small number of PSP organizations. The reduced generalizability of the results must be noted, as differences in jurisdiction, government policy, internal processes, resourcing, needs of the community being served, and other factors may affect the implementation, delivery, and use of the RP. Results may vary in other provinces, states, or countries.

5. Conclusions

Research and initiatives that address clinical interventions for PSP with OSIs have increased over the past decade. The topic warrants investigation, investment, and advocacy; however, the policies, processes, and programs that facilitate successful workplace reintegration post clinical treatment must also be addressed through evidence-based evaluation and consideration. The results of this initial qualitative study demonstrated that participants view the RP as facilitating mental health support and assisting in their return to work. The STCI also emerged as being viewed as favorable by participants for assisting those after a critical incident. This study also highlighted additional variables outside the RP that PSP perceived as impacting workplace reintegration, including stigma and additional sources of support. Access to evidence-based RPs may facilitate retention of PSP and enable PSP to continue to be engaged, present, and healthy as they serve their communities.

The EPS RP is a grassroots effort specifically created to support the return-to-duty process of PSP. It has undergone global spread and scale even with the absence of published literature, which demonstrates the need and desire for a focus on workplace reintegration among PSP. Rigorous, independent, and outcome-based research is still needed to help meet the RP objectives. By addressing workplace reintegration through innovation and research, future program iterations can provide continuously improving service and support for PSP and their communities.

Author Contributions

The study was conceptualized and designed by C.J., L.S.-M. and S.B.-P.; material preparation was performed by C.J. and S.B.-P.; data collection was conducted by C.J., E.O. and S.S.; data were analyzed by C.J., S.S., E.O. and S.B.-P.; the first draft of the manuscript was written by S.S., with ongoing editing of the draft performed by C.J., E.O., K.S.B., A.J.B., R.N.C., L.B., A.G., J.H., Y.Z., P.R.S., B.C. and S.B.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Supporting Psychological Health in First Responders (SPHIFR) Grant program through the Ministry of Labour and Immigration, Government of Alberta, Canada (21SPHIFHR24-2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta (1 March 2022/No. Pro00118357).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the sensitive nature of the data collected for this study, data are not available for sharing.

Acknowledgments

The research team at the Heroes in Mind, Advocacy and Research Consortium (HiMARC) would like to thank Edmonton Police Services, Calgary Police Services, Alberta Health Services Emergency Medical Services, the RCMP K-Division, and St. Albert Fire Services for their participation in and support of this study. Special thanks to Glen Klose, Colleen Mooney, Kevin Jerubic, and Ray Savage for their continued support of this research program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Turner, S.; Taillieu, T.; Duranceau, S.; LeBouthillier, D.M.; Sareen, J.; Ricciardelli, R.; Macphee, R.S.; Groll, D.; et al. Mental Disorder Symptoms among Public Safety Personnel in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 2018, 63, 54–64. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5788123/ (accessed on 13 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment (CIPSRT). Glossary of Terms: A Shared Understanding of the Common Terms Used to Describe Psychological Trauma (Version 2.1). 2019. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10294/9055 (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Glossary of Terms: A Shared Understanding of the Common Terms Used to Describe Psychological Trauma, Version 3.0, HPCDP: Vol 43(10/11), October/November 2023. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/health-promotion-chronic-disease-prevention-canada-research-policy-practice/vol-43-no-10-11-2023/glossary-common-terms-psychological-trauma-version-3-0.html (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; Text Revision; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bisson Desrochers, A.; Rouleau, I.; Angehrn, A.; Vasiliadis, H.M.; Saumier, D.; Brunet, A. Trauma on duty: Cognitive functioning in police officers with and without posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2021, 12, 1959117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgelow, M.M.; MacPherson, M.M.; Arnaly, F.; Tam-Seto, L.; Cramm, H.A. Occupational therapy and posttraumatic stress disorder: A scoping review. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 86, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Spencer, S.; Juby, B.; O’Greysik, E.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; Vincent, M.; Bremault-Phillips, S. Stakeholder experiences of a public safety personnel work reintegration program. J. Community Saf. Well-Being 2023, 8 (Suppl. S1), S23–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliphant, R.; Healthy Minds, Safe Communities: Supporting Our Public Safety Officers through a National Strategy for Operational Stress Injuries. Canadian House of Commons. 2016. Available online: https://www.ourcommons.ca/documentviewer/en/42-1/secu/report-5 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Wilson, S.; Guliani, H.; Boichev, G. On the economics of post-traumatic stress disorder among first responders in Canada. J. Community Saf. Well-Being 2016, 1, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nota, P.M.; Bahji, A.; Groll, D.; Carleton, R.N.; Anderson, G.S. Proactive psychological programs designed to mitigate posttraumatic stress injuries among at-risk workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer. How Much Are You Losing to Absenteeism? Our Thinking. Available online: https://www.mercer.ca/en/our-thinking/how-much-are-you-losing-to-absenteeism.html (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Price, J.A.B.; Ogunade, A.O.; Fletcher, A.J.; Ricciardelli, R.; Anderson, G.S.; Cramm, H.; Carleton, R.N. Peer Support for Public Safety Personnel in Canada: Towards a Typology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderland, K. Guidelines for the Practice and Training of Peer Support; Mishkin, W., Ed.; Mental Health Commission of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013; Available online: https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/resource/guidelines-for-the-practice-and-training-of-peer-support/ (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- Sutton, A.; Polaschek, D.L.L. Evaluating Return-to-Work Programmes after Critical Incidents: A Review of the Evidence. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 2022, 37, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; Pike, A.; Bright, K.S.; Bremault-Phillips, S. Effectiveness of a Workplace Reintegration Facilitator Training Program on Mental Health Literacy and Workplace Attitudes of Public Safety Personnel: Pilot Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Bright, K.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; Pike, A.D.; Brémault-Phillips, S. Peers supporting reintegration after operational stress injuries: A qualitative analysis of a workplace reintegration facilitator training program developed by municipal police for public safety personnel. Police J. Theory Pract. Princ. 2021, 95, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.S.; Di Nota, P.M.; Groll, D.; Carleton, R.N. Peer Support and Crisis-Focused Psychological Interventions Designed to Mitigate Post-Traumatic Stress Injuries among Public Safety and Frontline Healthcare Personnel: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahji, A.; Di Nota, P.M.; Groll, D.; Carleton, R.N.; Anderson, G.S. Psychological interventions for post-traumatic stress injuries among public safety personnel: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonton Police Services. Edmonton Police Services Reintegration Program: Final Report; Edmonton Police Services: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Klose, G.; Mooney, C.; McLeod, D. Reintegration: A New Standard in First Responder Peer Support. J. Community Saf. Wellbeing 2017, 2, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkin, S.; Schlundt, D.; Smith, P. Community-Engaged Research Perspectives: Then and Now. Acad. Pediatr. 2013, 13, 93–97. Available online: https://www.academicpedsjnl.net/article/S1876-2859(12)00330-0/fulltext (accessed on 2 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Esmail, L.; Moore, E.; Rein, A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: Moving from theory to practice. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2015, 4, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearman, M. Focus on Methodology: Eliciting rich data: A practical approach to writing semi-structured interview schedules. Focus Health Prof. Educ. A Multi-Prof. J. 2019, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.E. Qualitative Interview Questions: Guidance for Novice Researchers. Qual. Rep. 2020, 25, 3185–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.; Shamdasani, P.; Rook, D. Focus Groups, 2nd ed; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: Thousand Oaks , CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.L.; Adkins, D.; Chauvin, S. A Review of the Quality Indicators of Rigor in Qualitative Research. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, 138–146. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7055404/ (accessed on 2 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonenboom, J.; Johnson, R.B. How to Construct A mixed Methods Research Design. KZfSS Kölner Z. Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie 2017, 69, 107–131. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5602001/ (accessed on 2 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Conor, P.; Robson, J.; Marcellus, S. Police Resources in Canada, 2018; Government of Canada, Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019; Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2019001/article/00015-eng.htm (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Haugen, P.T.; McCrillis, A.M.; Smid, G.E.; Nijdam, M.J. Mental health stigma and barriers to mental health care for first responders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017, 94, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgelow, M.; Legassick, K.; Novecosky, J.; Fecica, A. Return to Work Experiences of Ontario Public Safety Personnel with Work-Related Psychological Injuries. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2023, 33, 796–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, C.; Fisher, A.; Jamiel, A.; Lynn, T.J.; Hill, W.T. Stigmatizing Attitudes Toward Police Officers Seeking Psychological Services. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 2018, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eerd, D.; Le Pouésard, M.; Yanar, B.; Irvin, E.; Gignac, M.A.M.; Jetha, A.; Morose, T.; Tompa, E. Return-to-Work Experiences in Ontario Policing: Injured but Not Broken. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2023, 34, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.P.; Papazoglou, K.; Koskelainen, M.; Nyman, M. Knowledge and Training Regarding the Link Between Trauma and Health. SAGE Open 2015, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliard, B. Utilization and Impact of Peer-Support Programs on Police Officers’ Mental Health. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgelow, M.; Scholefield, E.; McPherson, M.; Legassick, K.; Novecosky, J. Organizational Factors and Their Impact on Mental Health in Public Safety Organizations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetha, A.; Le Pouésard, M.; Mustard, C.; Backman, C.; Gignac, M.A.M. Getting the Message Right: Evidence-Based Insights to Improve Organizational Return-to-Work Communication Practices. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2021, 31, 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgelow, M.; Petrovic, A.; Gaherty, C.; Fecica, A. Occupational Therapy and Public Safety Personnel: Return to Work Practices and Experiences. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2024, 91, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosny, A.; Lifshen, M.; Pugliese, D.; Majesky, G.; Kramer, D.; Steenstra, I.; Soklaridis, S.; Carrasco, C. Buddies in Bad Times? The Role of Co-workers After a Work-Related Injury. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2013, 23, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunstan, D.A.; MacEachen, E. Bearing the Brunt: Co-workers’ Experiences of Work Reintegration Processes. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2013, 23, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysaght, R.M.; Larmour-Trode, S. An exploration of social support as a factor in the return-to-work process. Work 2008, 30, 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, M.; Mulhall, C.; Eppich, W. Breaking down barriers to help-seeking: Preparing first responders’ families for psychological first aid. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2022, 13, 2065430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, D.P.; Rachor, G.S.; Yamamoto, S.S.; Dick, B.D.; Brown, C.; Senthilselvan, A.; Straube, S.; Els, C.; Jackson, T.; Brémault-Phillips, S.; et al. Characteristics and Prognostic Factors for Return to Work in Public Safety Personnel with Work-Related Posttraumatic Stress Injury Undergoing Rehabilitation. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2021, 31, 768–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; O’Greysik, E.; Juby, B.; Spencer, S.; Vincent, M.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; Mooney, C.; Brémault-Phillips, S. How do we keep our heads above water? An Embedded Mixed-Methods Study Exploring Implementation of a Workplace Reintegration Program for Nurses Affected by Operational Stress Injury. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).