Psychological Distress and Associated Factors among Technical Intern Trainees in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Objective

2.2. Study Design and Setting

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Participants

2.5. Measurements

2.5.1. Assessment of Psychological Distress

2.5.2. Assessment of Demographic Factors and Other Health Conditions

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

| Frequency (n, %) | |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 304 (100) |

| Age, mean | 27.1 (SD—4.5) |

| Age group (years) | |

| 20–29 | 208 (68.4) |

| 30–38 | 96 (31.6) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 120 (39.5) |

| Female | 184 (60.5) |

| Nationality | |

| Vietnam | 202 (66.4) |

| Philippines | 75 (24.7) |

| Thailand | 12 (4.0) |

| Indonesia | 12 (4.0) |

| Other | 3 (0.9) |

| Line of work | |

| Food production | 180 (59.2) |

| Construction | 85 (28.0) |

| Nursing care | 32 (10.5) |

| Others | 7 (2.3) |

| Length of stay | |

| <1 year | 27 (9.1) |

| ≥1 year but <2 years | 47 (15.8) |

| ≥2 years but <3 years | 155 (52.0) |

| ≥3 years | 69 (23.1) |

| Conversational skills in Japanese | |

| Hardly able to converse in Japanese | 20 (6.6) |

| Enough for daily living | 138 (45.4) |

| Work purposes without issues | 144 (47.3) |

| Like a native | 2 (0.7) |

| Financial situation | |

| A little to very tough | 75 (24.7) |

| Okay | 201 (66.1) |

| A little to significant surplus | 28 (9.2) |

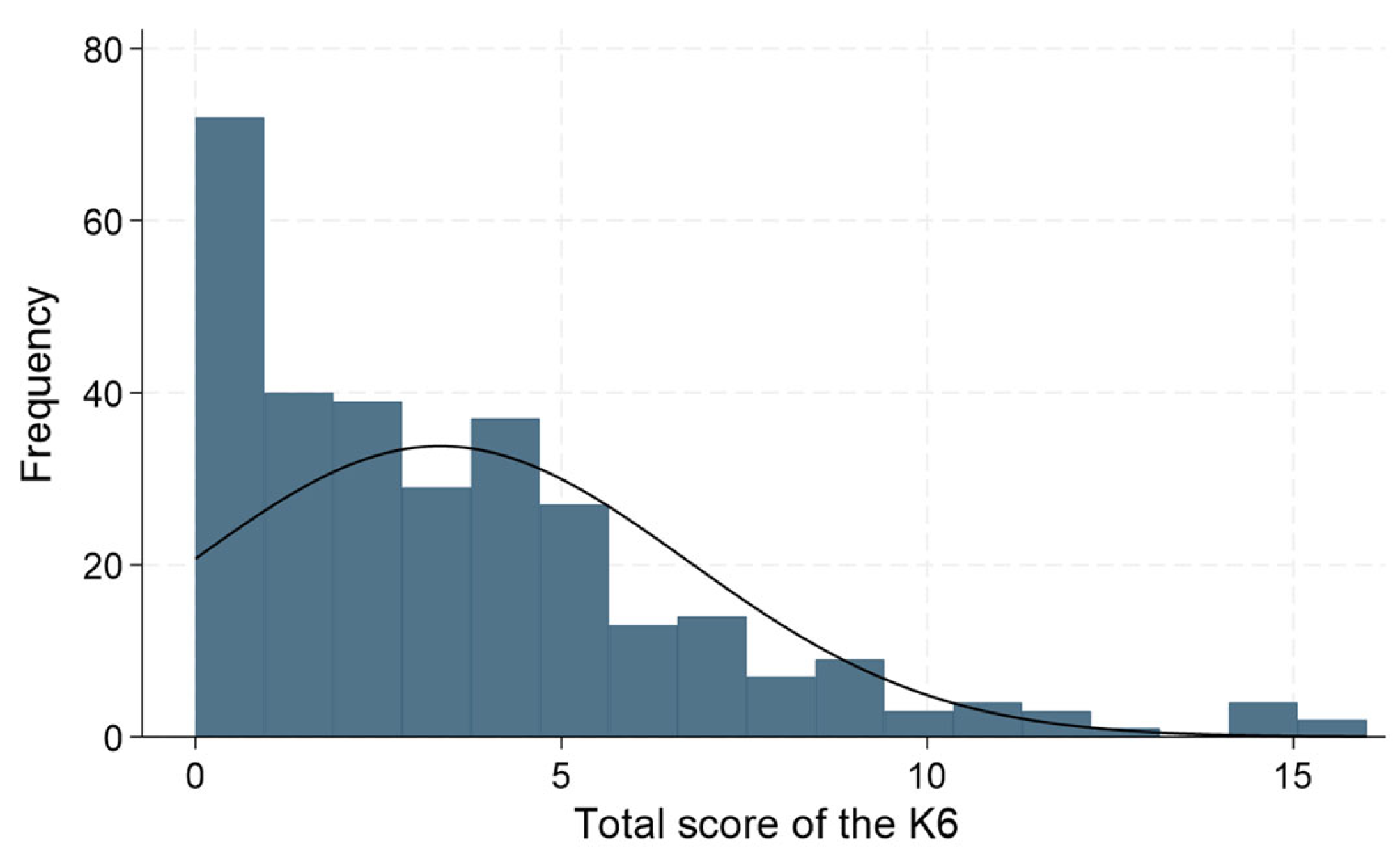

3.2. Psychological Distress and Health Condition of the Participants

| Frequency (n, %) | |

|---|---|

| Psychological distress | |

| No distress (K6 < 5) | 217 (71.4) |

| Moderate distress (5 ≤ K6 < 13) | 80 (26.3) |

| Severe distress (K6 ≥ 13) | 7 (2.3) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |

| <18.5 | 31 (10.2) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 253 (83.2) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 20 (6.6) |

| Self-reported health condition | |

| Good to excellent | 249 (81.9) |

| Not so good/poor | 55 (18.1) |

| Experienced a sense of insecurity or concern about health | |

| Yes | 45 (14.8) |

| No | 257 (85.2) |

| Wanted to see a doctor but ended up not going | |

| Yes | 46 (15.1) |

| No | 258 (84.9) |

3.3. Factors Associated with Moderate Psychological Distress

| K6 < 5 (n = 217) | K6 ≥ 5 (n = 87) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age group (years) | |||

| 20–29 | 148 (68.2) | 60 (69.0) | 0.88 |

| 30–38 | 69 (31.8) | 27 (31.0) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 95 (43.8) | 25 (28.7) | <0.05 |

| Female | 122 (56.2) | 62 (71.2) | |

| Nationality | |||

| Vietnam | 163 (75.1) | 39 (44.8) | <0.001 |

| Philippines | 37 (17.0) | 38 (43.7) | |

| Thailand | 7 (3.2) | 5 (5.7) | |

| Indonesia | 7 (3.2) | 5 (5.7) | |

| Other | 3 (1.4) | 0 | |

| Line of work | |||

| Food production | 121 (55.8) | 59 (67.8) | 0.47 |

| Construction | 65 (30.0) | 20 (23.0) | |

| Nursing care | 25 (11.5) | 7 (8.0) | |

| Others | 6 (2.7) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Length of stay | |||

| Less than 2 years | 56 (25.8) | 18 (20.7) | 0.35 |

| 2 years and more | 161 (74.2) | 69 (79.3) | |

| Conversational skills in Japanese | |||

| Hardly able to converse in Japanese | 11 (5.1) | 9 (10.3) | 0.14 |

| Enough for daily living | 96 (44.2) | 42 (48.3) | |

| Work purposes without issues | 110 (50.7) | 36 (41.4) | |

| Like a native | |||

| Financial situation | |||

| A little to very tough | 171 (78.8) | 58 (66.7) | <0.05 |

| Okay/surplus | 46 (21.2) | 29 (33.3) | |

| Experience of health insecurity | |||

| Yes | 25 (11.5) | 20 (23.0) | <0.05 |

| No | 192 (88.5) | 67 (77.0) | |

| Wanted to see a doctor but ended up not going | |||

| Yes | 22 (10.1) | 24 (27.6) | <0.001 |

| No | 195 (89.9) | 63 (72.4) |

| Variable | Crude | Adjusted # | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | AOR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Ref | Ref | ||

| Female | 1.93 (1.13–3.30) | 0.016 * | 2.62 (1.12–6.12) | 0.026 * |

| Nationality | ||||

| Vietnamese | Ref | Ref | ||

| Other | 3.72 (2.20–6.26) | <0.001 *** | 4.85 (2.60–9.07) | <0.001 *** |

| Financial condition | ||||

| Okay/surplus | Ref | Ref | ||

| A little to very tough | 1.86 (1.07–3.23) | 0.028 * | 2.23 (1.18–4.19) | 0.013 * |

| Experience of health insecurity | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2.30 (1.19–4.39) | 0.012 * | 2.21 (1.04–4.67) | 0.038 * |

| Wanted to see a doctor but ended up not going | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 3.38 (1.77–6.43) | <0.001 *** | 3.06 (1.49–6.30) | 0.002 ** |

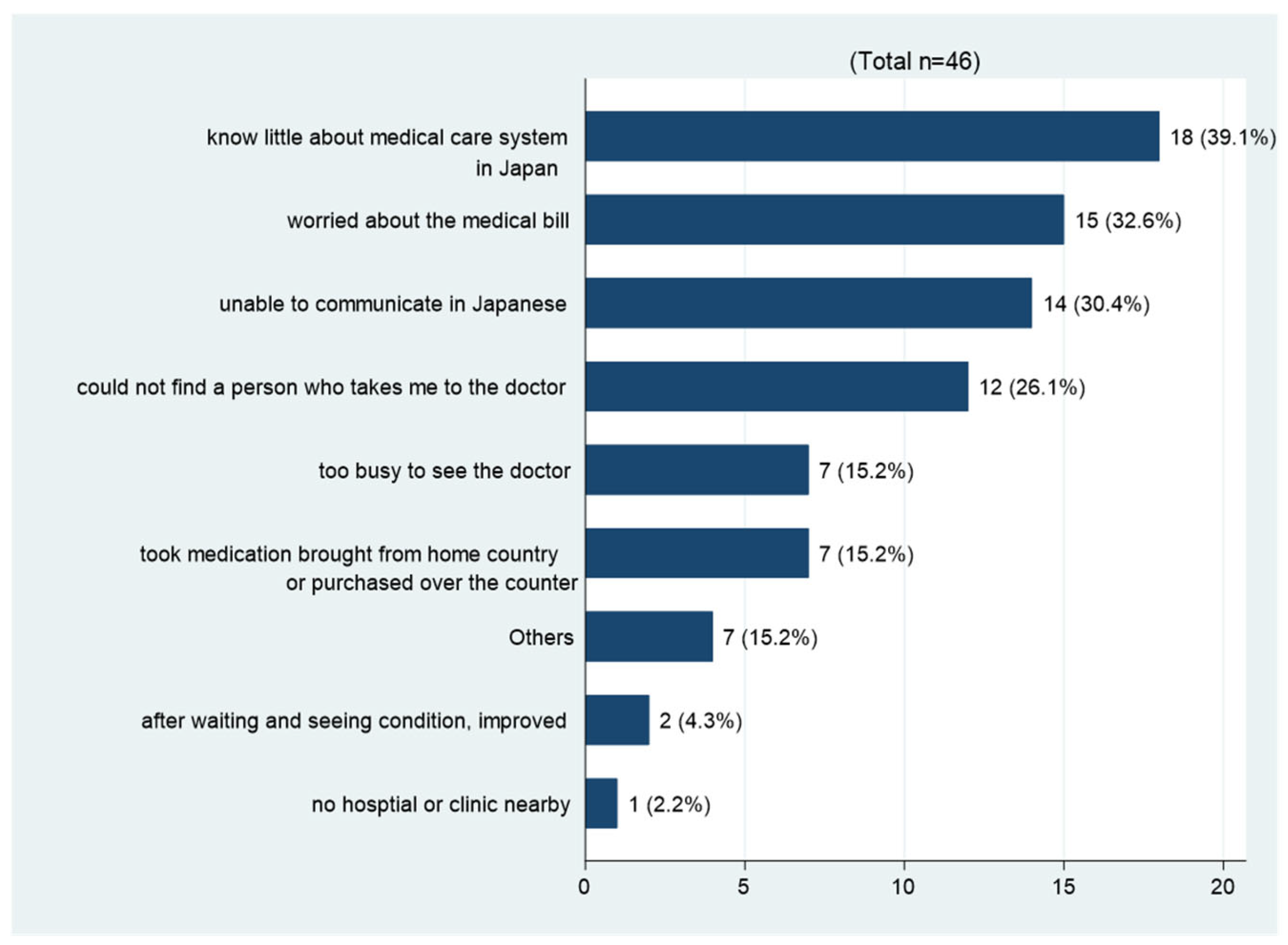

3.4. Health-Seeking Behaviors and Barriers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, R.S.; Seitani, H. Labour market reform in Japan to cope with a shrinking and ageing population. OECD Econ. Dep. Work. Pap. 2019, 1568, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaguchi, K. How have Japanese policies changed in accepting foreign workers? Jpn. Labor. Issues 2019, 3, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. About the Foreign Technical Internship System. 2023. Available online: https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/content/930005177.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2023). (In Japanese)

- Davies, A.A.; Basten, A.; Frattini, C. Migration: A social determinant of the health of migrants. Eurohealth 2009, 16, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Aktas, E.; Bergbom, B.; Godderis, L.; Kreshpaj, B.; Marinov, M.; Mates, D.; McElvenny, D.M.; Mehlum, I.S.; Milenkova, V.; Nena, E.; et al. Migrant workers occupational health research: An OMEGA-NET working group position paper. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2022, 95, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bener, A. Health Status and Working Condition of Migrant Workers: Major Public Health Problems. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 8, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mucci, N.; Traversini, V.; Giorgi, G.; Tommasi, E.; De Sio, S.; Arcangeli, G. Migrant workers and psychological health: A systematic review. Sustainability 2019, 12, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnayake, P.; De Silva, S.; Kage, R. Workforce development with Japanese technical intern training program in Asia: An overview of performance. Saga Univ. Econ. Rev. 2016, 49, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Status of Supervision, Guidance, and Detention of Foreign Technical Intern Trainees’ Training Providers. 2017. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/houdou/0000212372.html (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Hane Aida, Y.M. Literature review of the health of technical intern trainees in Japan: A study using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi 2021, 63, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K. Risk factors for mental health of Technical Intern Trainees from Philippines. J. Int. Health 2018, 33, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koji, S. A International Comparative Study on the Acceptance System of Foreign Workers in Japan and Korea: Focusing on low-skilled workers. J. Korean Econ. Stud. 2020, 17, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujimura, H. A review of research on Technical Intern Trainees’ health and life problems. J. Jpn. Soc. Int. Nurs. 2020, 3, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, M.; Endo, M.; Yoshino, A. Factors associated with access to health care among foreign residents living in Aichi Prefecture, Japan: Secondary data analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudva, K.G.; El Hayek, S.; Gupta, A.K.; Kurokawa, S.; Bangshan, L.; Armas-Villavicencio, M.V.C.; Oishi, K.; Mishra, S.; Tiensuntisook, S.; Sartorius, N. Stigma in mental illness: Perspective from eight Asian nations. Asia-Pac. Psychiatry 2020, 12, e12380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauber, C.; Rössler, W. Stigma towards people with mental illness in developing countries in Asia. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2007, 19, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swartz, J.A.; Jantz, I. Association Between Nonspecific Severe Psychological Distress as an Indicator of Serious Mental Illness and Increasing Levels of Medical Multimorbidity. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 2350–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Mino, Y.; Uddin, S. Strategies and future attempts to reduce stigmatization and increase awareness of mental health problems among young people: A narrative review of educational interventions. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 65, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamawaki, N.; Pulsipher, C.; Moses, J.D.; Rasmuse, K.R.; Ringger, K.A. Predictors of negative attitudes toward mental health services: A general population study in Japan. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2011, 25, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, P.C.F.; Too, L.S.; Butterworth, P.; Witt, K.; Reavley, N.; Milner, A.J. A systematic review on the effect of work-related stressors on mental health of young workers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 93, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, A.; Okumi, H.; Matsuoka, H.; Makimura, C.; Sakamoto, R.; Sakai, K. The physical and psychological problems of immigrants to Japan who require psychosomatic care: A retrospective observation study. BioPsychoSocial Med. 2016, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas-Sarmiento, P.; Saucedo-Moreno, M.J.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, M.; Poza-Méndez, M. Mental Health in Immigrants Versus Native Population: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brydsten, A.; Rostila, M.; Dunlavy, A. Social integration and mental health—A decomposition approach to mental health inequalities between the foreign-born and native-born in Sweden. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertsson, T.; Kokko, S.; Lilja, E.; Castañeda, A.E. Prevalence and risk factors of psychological distress among foreign-born population in Finland: A population-based survey comparing nine regions of origin. Scand. J. Public. Health 2023, 51, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handiso, D.W.; Paul, E.; Boyle, J.A.; Shawyer, F.; Meadows, G.; Enticott, J.C. Trends and determinants of mental illness in humanitarian migrants resettled in Australia: Analysis of longitudinal data. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcão, V.; Candeias, P.; Stefanovska-Petkovska, M.; Pintassilgo, S.; Machado, F.L.; Virgolino, A.; Santos, O. Mental Health and Well-Being of Migrant Populations in Portugal Two Years after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumaa, J.A.; Bendau, A.; Ströhle, A.; Heinz, A.; Betzler, F.; Petzold, M.B. Psychological distress and anxiety in Arab refugees and migrants during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Transcult. Psychiatry 2023, 60, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barker, P.R.; Colpe, L.J.; Epstein, J.F.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Normand, S.-L.T.; Manderscheid, R.W.; Walters, E.E.; et al. Screening for Serious Mental Illness in the General Population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batterham, P.; Sunderland, M.; Slade, T.; Calear, A.; Carragher, N. Assessing distress in the community: Psychometric properties and crosswalk comparison of eight measures of psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 1316–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mewton, L.; Kessler, R.C.; Slade, T.; Hobbs, M.J.; Brownhill, L.; Birrell, L.; Tonks, Z.; Teesson, M.; Newton, N.; Chapman, C. The psychometric properties of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6) in a general population sample of adolescents. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staples, L.G.; Dear, B.F.; Gandy, M.; Fogliati, V.; Fogliati, R.; Karin, E.; Nielssen, O.; Titov, N. Psychometric properties and clinical utility of brief measures of depression, anxiety, and general distress: The PHQ-2, GAD-2, and K-6. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2019, 56, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Green, J.G.; Gruber, M.J.; Sampson, N.A.; Bromet, E.; Cuitan, M.; Furukawa, T.A.; Gureje, O.; Hinkov, H.; Hu, C.Y. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: Results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2010, 19, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, T.A.; Kawakami, N.; Saitoh, M.; Ono, Y.; Nakane, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Tachimori, H.; Iwata, N.; Uda, H.; Nakane, H. The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2008, 17, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, J.W.; Chia, C.; Koh, C.J.; Chua, B.W.B.; Narayanaswamy, S.; Wijaya, L.; Chan, L.G.; Goh, W.L.; Vasoo, S. Healthcare-seeking behaviour, barriers and mental health of non-domestic migrant workers in Singapore. BMJ Glob. Health 2017, 2, e000213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brijnath, B.; Antoniades, J.; Temple, J. Psychological distress among migrant groups in Australia: Results from the 2015 National Health Survey. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, D.; Mendieta-Marichal, Y.; Martínez-Ortega, J.M.; Agrela, M.; Ariza, C.; Gutiérrez-Rojas, L.; Araya, R.; Lewis, G.; Gurpegui, M. World region of origin and common mental disorders among migrant women in Spain. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2014, 16, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prochaska, J.J.; Sung, H.-Y.; Max, W.; Shi, Y.; Ong, M. Validity study of the K6 scale as a measure of moderate mental distress based on mental health treatment need and utilization. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 21, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagasu, M.; Muto, K.; Yamamoto, I. Impacts of anxiety and socioeconomic factors on mental health in the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic in the general population in Japan: A web-based survey. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.; Tomita, Y.; Ong, K.I.C.; Shibanuma, A.; Jimba, M. Mental well-being of international migrants to Japan: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, B.; Yaskina, M.; Hegadoren, K.; Diaz, E.; Meherali, S.; Rammohan, A.; Ben-Shlomo, Y. Migration and social determinants of mental health: Results from the Canadian Health Measures Survey. Can. J. Public. Health 2017, 108, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedraza, S. Women and migration: The social consequences of gender. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1991, 17, 303–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.M.; Wallace, S.P. Migration circumstances, psychological distress, and self-rated physical health for Latino immigrants in the United States. Am. J. Public. Health 2013, 103, 1619–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. ILO Global Estimates on International Migrant Workers; Results and Methodology. 2018. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_652001.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Summary of “Status of Employment of Foreign Nationals” (as of October 31, 2022). Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_30367.html (accessed on 2 March 2024). (In Japanese)

- Uezato, A.; Sakamoto, K.; Miura, M.; Futami, A.; Nakajima, T.; Quy, P.N.; Jeong, S.; Tomita, S.; Saito, Y.; Fukuda, Y.; et al. Mental health and current issues of migrant workers in Japan: A cross-sectional study of Vietnamese workers. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2024, 70, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, T.; Quy, P.N.; Nogami, E.; Seto-Suh, E.; Yamada, C.; Iwamoto, S.; Shimazawa, K.; Kato, K. Depression and anxiety symptoms among Vietnamese migrants in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Trop. Med. Health 2023, 51, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Nguyen, N.H.T.; Takaoka, S.; Do, A.D.; Shirayama, Y.; Nguyen, Q.P.; Akutsu, Y.; Takasaki, J.; Ohkado, A. A Study on the Health-Related Issues and Behavior of Vietnamese Migrants Living in Japan: Developing Risk Communication in the Tuberculosis Response. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhopal, R.; Rafnsson, S. Global inequalities in assessment of migrant and ethnic variations in health. Public Health 2012, 126, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Routen, A.; Akbari, A.; Banerjee, A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Mathur, R.; McKee, M.; Nafilyan, V.; Khunti, K. Strategies to record and use ethnicity information in routine health data. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1338–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supakul, S.; Jaroongjittanusonti, P.; Jiaranaisilawong, P.; Phisalaphong, R.; Tanimoto, T.; Ozaki, A. Access to Healthcare Services among Thai Immigrants in Japan: A Study of the Areas Surrounding Tokyo. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aida, H.; Mori, Y.; Tsujimura, H.; Sato, Y. Health of technical intern trainees: One-year qualitative longitudinal study after arrival in Japan. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2023, 70, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Editorial, End of Technical Intern Program: Use Reformed System to Improve Working Environment for Foreigners. The Japan News by The Yomiuri Shinbun. 2024. Available online: https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/editorial/yomiuri-editorial/20240210-168083/ (accessed on 21 February 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khin, E.T.; Takeda, Y.; Iwata, K.; Nishimoto, S. Psychological Distress and Associated Factors among Technical Intern Trainees in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21080963

Khin ET, Takeda Y, Iwata K, Nishimoto S. Psychological Distress and Associated Factors among Technical Intern Trainees in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(8):963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21080963

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhin, Ei Thinzar, Yuko Takeda, Kazunari Iwata, and Shuhei Nishimoto. 2024. "Psychological Distress and Associated Factors among Technical Intern Trainees in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 8: 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21080963

APA StyleKhin, E. T., Takeda, Y., Iwata, K., & Nishimoto, S. (2024). Psychological Distress and Associated Factors among Technical Intern Trainees in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(8), 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21080963