Workplace Bullying and Harassment in Higher Education Institutions: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Workplace Bullying and Harassment in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs)

2. Methods

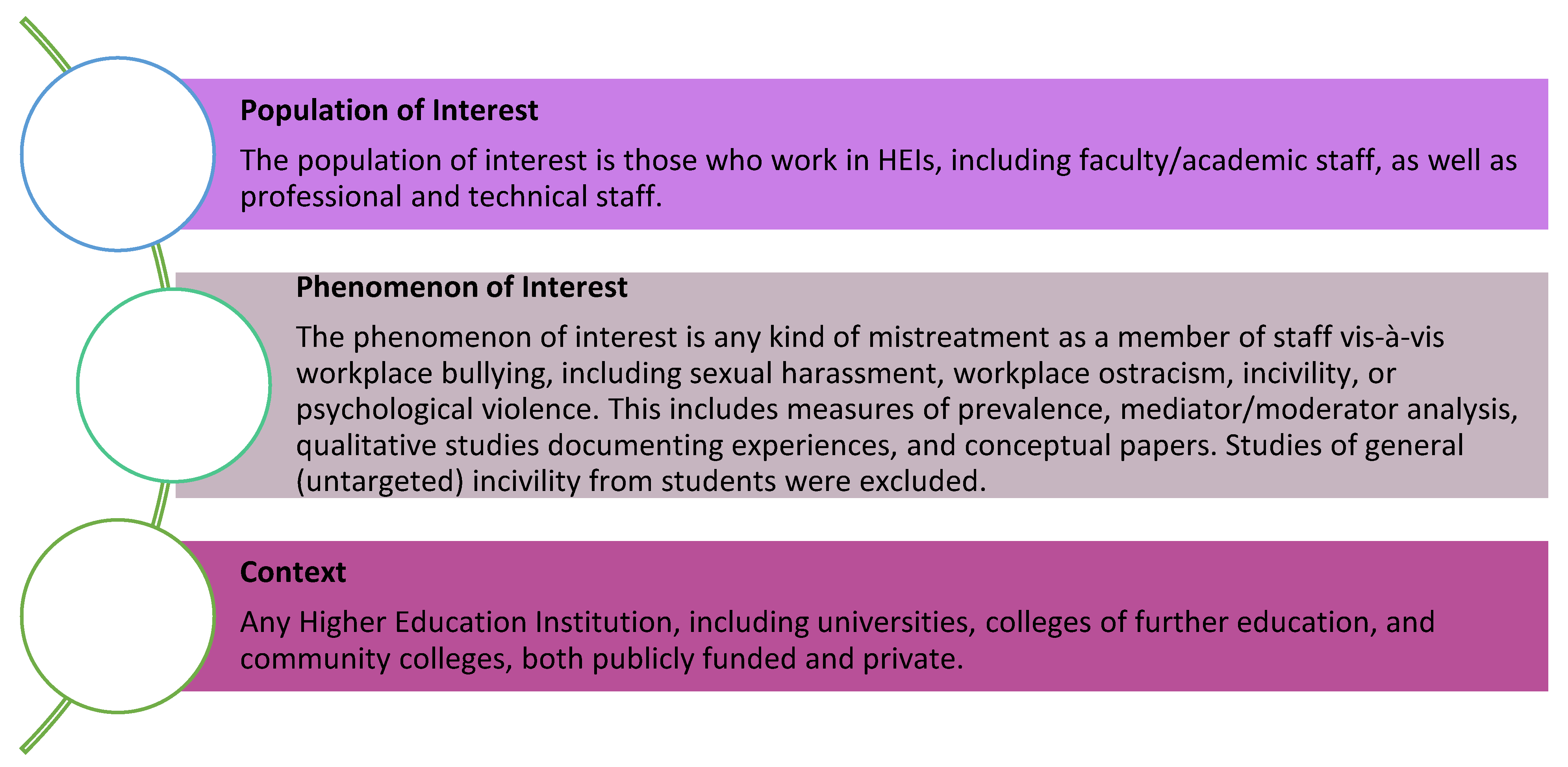

2.1. Research Questions

2.2. Identification of Relevant Studies

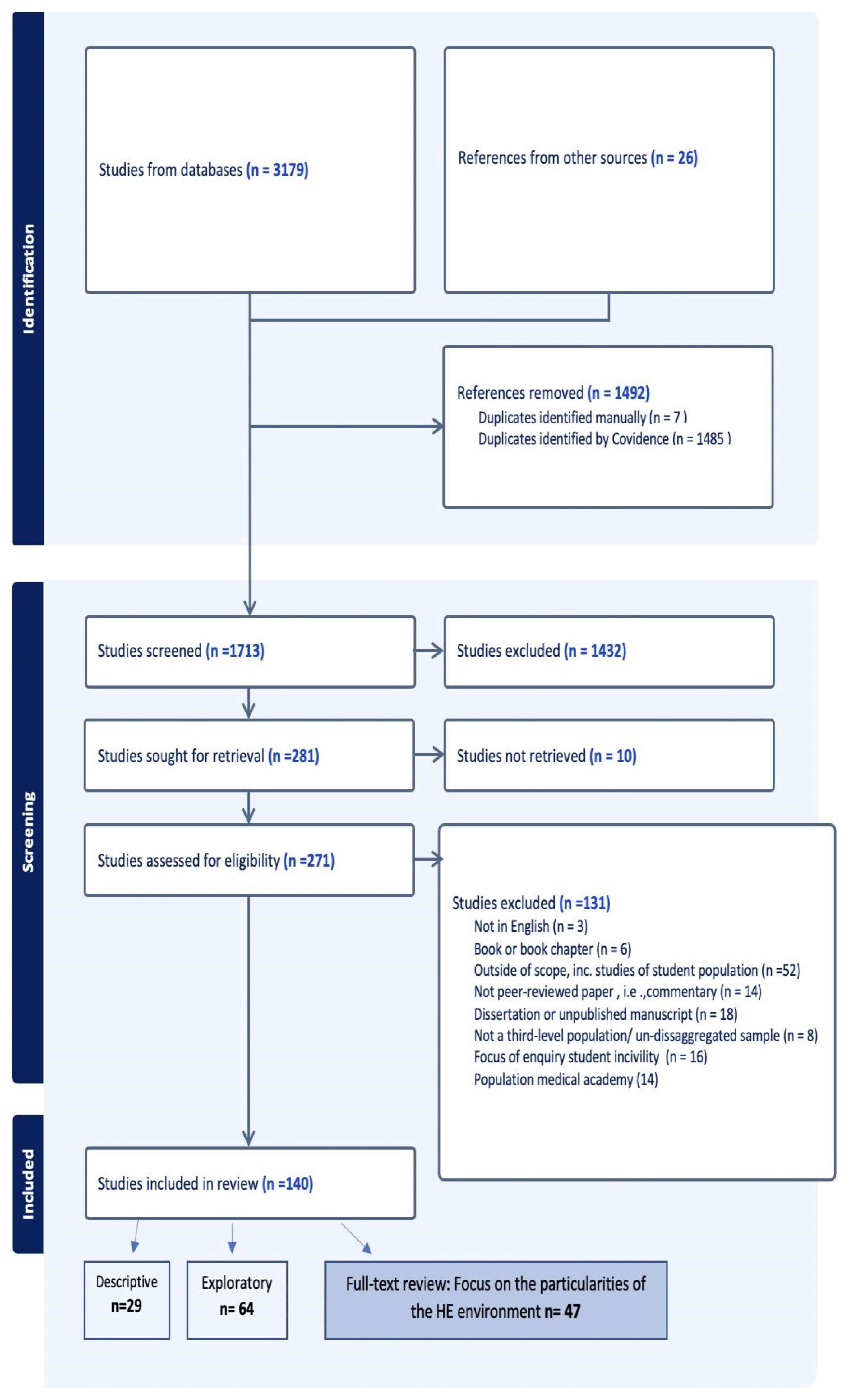

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Charting

- Studies that are primarily descriptive, viz., descriptive reporting of levels of exposure with demographic or other (e.g., section or staff group) breakdown. The context is a workplace (n = 29).

- Studies that are exploratory, i.e., aiming to advance the understanding of bullying and harassment through moderators, mediators, and/or processes and organisational nuances. The context is the workplace as a complex organisation (n = 64).

- The focus on is on the particularities of the HE environment (beyond the brief mention of high levels of bullying/the topic being understudied, etc.), including power differentials in the context of gender inequity or students, and/or (b) the challenges inherent in the changing context of HE. Category three does not preclude category two. The categorisation is on the basis of the inclusion of contextual discussion within the paper (n = 47).

3. Results

3.1. Collation and Summary of Data

3.2. The Impact of Neoliberalism

3.2.1. Neoliberalism Compounds Existing Contextual Factors

3.2.2. Precarity and Job Insecurity

3.3. Complex and Malevolent Gendered Power Dynamics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nielsen, M.; Einarsen, S. What we know, what we do not know, and what we should and could have known about workplace bullying: An overview of the literature and agenda for future research. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 42, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgins, M.; Mannix McNamara, P. Bullying and incivility in higher education workplaces: Micropolitics and the abuse of power. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. Int. J. 2017, 12, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S. The nature and causes of bullying at work. Int. J. Manpow. 1999, 20, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fevre, R.; Lewis, D.; Robinson, A.; Jones, T. Insight into Ill-Treatment in the Workplace: Patterns, Causes and Solutions; Cardiff School of Social Sciences: Cardiff, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, C.; Porath, C. On the nature, consequences and remedies of workplace incivility: No time for “nice”? Think again. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2005, 19, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilpzand, P.; De Pater, I.E.; Erez, A. Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 57–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.V.; Hoel, H.; Zapf, D.; Cooper, C.L. The Concept of Bullying and Harassment at Work: The European Tradition. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace Theory, Research and Practice; Einarsen, S.V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2020; pp. 3–53. [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Heyndyk, R. Quarter of BAME Staff Bullied or Harassed at Work. HR. 2019. Available online: https://pearnkandola.com/press/quarter-of-bame-staff-bullied-or-harassed-at-work/ (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Nielsen, M.B.; Bjorkelo, B.; Notelaers, G.; Einarsen, S. Sexual Harassment: Prevalence, Outcomes, and Gender Differences Assessed by Three Different Estimation Methods. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2010, 19, 252–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoel, H.; Lewis, D.; Einarsdottir, A. The Ups and Downs of LGBs’ Workplace Experiences: Discrimination, Bullying and Harassment of Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Employees in Britain; Manchester University Business School: Manchester, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf, D.; Einarsen, S. Bullying in the workplace: Recent Trends in research and practice. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2001, 10, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosander, M.; Nielsen, M.; Blomberg, S. The last resort: Workplace bullying and the consequences of changing jobs. Health Work Psychol. 2022, 63, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L.; Areguin, M.A. Putting People Down and Pushing Them Out: Sexual Harassment in the Workplace. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2021, 8, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, E.G.; Hansen, A.M.; Persson, R.; Byrgesen, M.F.; Hogh, A. Individual Consequences of Being Exposed to Workplace Bullying. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace Theory, Research and Practice; Einarsen, S.V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2020; pp. 163–208. [Google Scholar]

- Richman, J.A.; Rospenda, K.M.; Nawyn, S.J.; Flaherty, J.A.; Fendrich, M.; Drum, M.L.; Johnson, T.P. Sexual Harassment and Generalized Workplace Abuse Among University Employees:Prevalence and Mental Health Correlates. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, P. Workplace Sexual Harassment 30 Years on: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2012, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L.M.; Berdahl, J.L. Sexual harassment in organizations: A decade of research in review. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Behavior: Vol. I. Micro Approaches; Cooper, C.L., Ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 469–497. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M. Nurse bullying: Organizational considerations in the maintenance and perpetration of health care bullying cultures. J. Nurs. Manag. 2006, 14, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. Will the real bully please stand up. Occup. Health 2004, 56, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- O’Moore, M.; Seigne, E.; McGuire, L.; Smith, M. Victims of workplace bullying in Ireland. Ir. J. Psychol. 1998, 19, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgins, M.; McNamara, P.M. An Enlightened Environment? Workplace Bullying and Incivility in Irish Higher Education. SAGE Open 2019, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cruz, P.; Noronha, E. Clarifying My World: Identity Work in the Context of Workplace Bullying. Qual. Rep. 2012, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogh, A.; Mikklesen, E.G.; Hansen, A.M. Individual consequences of workplace bullying/mobbing. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace; Einarsen, S.H.H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- De Vos, J.; Kirsten, G.J.C. The nature of workplace bullying experienced by teachers and the biopsychosocial health effects. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2015, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoel, H.; Faragher, B.; Cooper, C.L. Bullying is detrimental to health, but all bullying behaviours are not necessarily equally damaging. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2004, 32, 367–387. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, J.; Hutchinson, M.; Jackson, D.; Bradbury, J.; Browne, G. Nexus between preventive policy inadequacies, workplace bullying, and mental health: Qualitativefindings from the experiences of Australian public sector employees. Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 25, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D. Bullying at work: The impact of shame among university and college lecturers. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2004, 32, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallberg, L.R.M.; Strandmark, M.K. Health consequences of workplace bullying: Experiences from the perspective of employees in the public service sector. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2006, 1, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naezer, M.; Benschop, Y.; van den Brink, M.C.L. Harassment in Dutch Academics. Exploring Manifestations, Facilitataing Factors, Effects and Solutions; Landelijk Netwerk Vrouwelijke Hoogleraren: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf, D.; Escartin, J.; Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Vartia, M. Empirical Findings on Prevalance and Risk Groups of Bullying in the Workplace. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace; Einarsen, S.V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf, D.; Escartin, J.; Scheppa-Lahyani, M.; Einarsen, S.V.; Hoel, H.; Vaartia, M. Empirical Findings on Prevalence and Risk Groups of Bullying in the Workplace. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace, 3rd ed.; Einarsen, S.V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Reknes, I.; Einarsen, S.; Gejerstad, J.; Nielsen, M. Dispositional affect as a moderator in the relationship between role conflict and exposure to bullying behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Brande, W.; Baillien, E.; De Witte, H.; Vander Elst, T.; Godderis, L. The role of work stressors, coping strategies and coping resources in the process of workplace bullying: A systematic review and development of a comprehensive model. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2016, 29, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauge, L.J.; Skogstad, A.; Einarsen, S. Individual and situational predictors of workplace bullying: Why do perpetrators engage in the bullying of others? Work Stress 2009, 23, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, P.J.; Calvert, E.; Watson, D. Bullying in the Workplace: Survey Reports; Economic and Social Research Institute: Dublin, Ireland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins, M.; Lewis, D.; MacCurtain, S.; Mannix McNamara, P.; Pursell, L.; Hogan, V. ‘…a bit of a Joke’: Policy and workplace bullying. SAGE Open 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S. Restructuring workplace cultures: The ultimate work-familiy challenge? Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2010, 25, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S. Nursing Workforce Retention: Challenging a Bullying Culture. Health Aff. 2002, 21, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijfeijken, T. “Culture Is What You See When Compliance Is Not in the Room”: Organizational Culture as an Explanatory Factor in Analyzing Recent INGO Scandals. Nonprofit Policy Forum 2019, 10, 20190031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leymann, H. The content and development of mobbing at work. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1996, 5, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, D. Ways of Explaining Workplace Bullying: A Review of Enabling, Motivating and Precipitating Structures and Processes in the Work Environment. Hum. Relat. 2003, 56, 1213–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefooghe, A.P.D.; MacDavey, K. Accounts of Workplace Bullying: The Role of the Organisation. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2010, 10, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgins, M.; MacCurtain, S.; Mannix McNamara, P. Power and inaction: Why organizations fail to address workplace bullying. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2020, 13, 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cruz, P.; Noronha, E. Experiencing depersonalised bullying: A study of Indian call-centre agents. Work. Organ. Labour Glob. 2009, 3, 26–46. [Google Scholar]

- Branch, S.; Shallcross, L.; Barker, M.; Ramsay, S.; Murray, J.P. Theoretical Frameworks That Have Explained Workplace Bullying: Retracing Contributions Across the Decades. In Concepts Approachs and Methods; D’Cruz, P., Noronha, E., Notelaers, G., Rayner, C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 87–130. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.; Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J. Personal and workgroup incivility: Impact on work and health outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giga, S.I.; Hoel, H.; Lewis, D. The Costs of Workplace Bullying; Universities of Bradford: Manchester, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hoel, H.; Sparks, K.; Cooper, C.L. The Cost of Violence/Stress at Work and the Benefits of a Violence/Stress-Free Working Environment; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan, J.; Hodgins, M.; Hogan, V.; Pursell, L. The value of lost productivity from workplace bullying in Ireland. Occup. Med. 2020, 70, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirlwall, A. Organisational sequestering of workplace bullying: Adding insult to injury. J. Manag. Organ. 2015, 21, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodrow, C.; Guest, D.E. When good HR gets bad results: Exploring the challenge of HR implementation in the case of workplace bullying. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2013, 24, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgins, M.; Pursell, L.; Hogan, V.; MacCurtain, S.; Mannix-McNamara, P. Irish Workplace Behaviour Study; Institute of Occupational Safety Health: Wigston, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- D’Cruz, P.; Norohna, E.; Mendonca, A.; Bhatt, R. Engaging with the East: Showcasing workplace bullying in Asia. In Asian Perspectives on Workplace Bullying and Harassment; D’Cruz, P., Norohna, E., Mendonca, A., Bhatt, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Keashly, L.; Neuman, J.H. Faculty Experiences with Bullying in Higher Education. Adm. Theory Prax. (ME Sharpe) 2010, 32, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskauskas, J. Bullying in Academia: An Examination of Workplace Bullying in New Zealand Universities; American Education Research Association: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Conco, D.N.; Baldwin-Ragaven, L.; Christofides, N.J.; Libhaber, E.; Rispel, L.C.; White, J.A.; Kramer, B. Experiences of workplace bullying among academics in a health sciences faculty at a South African university. S. Afr. Med. J. 2021, 111, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, R.; Arnold, D.H.; Fratzl, J.; Thomas, R. Workplace Bullying in Academia: A Canadian Study. Empl. Rights Responsib. J. 2008, 20, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M. Bullying among support staff in a higher education instituion. Health Educ. 2004, 105, 273287. [Google Scholar]

- Bondestam, F.; Lundqvist, M. Sexual harassment in higher education—A systematic review. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2020, 10, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Task Force on the Prevention of Workplace Bullying; Economic and Social Research Institute: Dublin, Ireland, 2001.

- Baillien, E.; Griep, Y.; Vander Elst, T.; De Witte, H. The relationship between organisational change and being a perpetrator of workplace bullying: A three-wave longitudinal study. Work Stress 2018, 33, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercelle, J.; Murphy, E. The Neoliberalisation of Irish Higher Education under Austerity. Crit. Sociol. 2017, 43, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, J. The Toxic University. Zombie Leadership. Academic Rock Stars, and Neoliberal Ideology; Palgrave: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ivancheva, M.; Lynch, K.; Keating, K. Precarity, gender and care in the neoliberal academy. Gend. Work. Organ. 2019, 26, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K.; Ivancheva, M. Academic freedom and the commercialisation of universities: A critical ethical analysis. Ethics Sci. Environ. Politics 2015, 15, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P. Why is it so difficult to reduce gender inequality in male-dominated higher educational organizations? A feminist institutional perspective. Interdiscip. Sci. Rev. 2020, 45, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, L.; Batrtneck, C.; Voges, K. Over-Competitiveness in Academia: A Literature Review. Disruptive Sci. Technol. 2013, 1, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binswanger, M. Excellence by Nonesense: The Competition for Publications in Modern Science. Open. Sci. 2014, 8, 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf, D.; Vaartia, M. Prevention and treatment of workplace bullying: An overview. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace Theory Research and Practice; Einarsen, S.V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Keashly, L.; Neuman, J. Bullying in Higher Education: What Current Research, Theorizing and Practice tell us. In Wotrkplace Bullying in Higher Education; Lester, J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Henning, M.A.; Zhou, C.; Adams, P.; Moir, F.; Hobson, J.; Hallett, C.; Webster, C.S. Workplace harassment among staff in higher education: A systematic review. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2017, 18, 521–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, H.S.; Hosier, S.; Zhang, H. Prevalence, Antecedents, and Consequences of Workplace Bullying among Nurses—A Summary of Reviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colaprico, C.; Addari, S.; La Torre, G. The effects of bullying on healthcare workers: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Riv. Psichiatr. 2023, 58, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromatrais, E.; Munn, Z. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. TPRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Internal Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlingieri, A. Workplace bullying: Exploring an emerging framework. Work Employ. Soc. 2015, 29, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgins, M.; MacCurtain, S.; Mannix-McNamara, P. Workplace Bullying and Incivility: A systematic review of interventions. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2014, 7, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.; Indregard, A.-M.; Overland, S. Workplace bullying and sickness absence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the research literature. Scandanavian J. Work Environ. Health 2016, 42, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijó, F.R.; Gräf, D.D.; Pearce, N.; Fassa, A.G. Risk factors for workplace bullying: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillen, P.A.S.M.; Kernohan, W.G.; Begley, C.M.; Luyben, A.G. Interventions for Prevention of Bullying in the Workplace. Cochrane. DB Syst. Rev. 2017, 1, CD009778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.M. Theory and Method on the Social Sciences; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Meriläinen, M.; Sinkkonen, H.; Puhakka, H.; Käyhkö, K. Bullying and inappropriate behaviour among faculty personnel. Policy Futures Educ. 2016, 14, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. Students and managers behaving badly: An exploratory analysis of the vulnerability of feminist academics in anti-feminist, market-driven UK higher education. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2005, 28, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzki, M.; Jensen, T. Bullying and the neoliberal university: A co-authored autoethnography. Manag. Learn. 2020, 51, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabrodska, K.; Linnell, S.; Laws, C.; Davies, B. Bullying as intra-active process in neoliberal universities. Qual. Inq. 2011, 17, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P.; Hodgins, M.; Woods, D.R.; Wallwaey, E.; Palmen, R.; Van Den Brink, M.; Schmidt, E.K. Organisational Characteristics That Facilitate Gender-Based Violence and Harassment in Higher Education? Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdemir, B.; Demir, C.E.; Yıldırım Öcal, J.; Kondakçı, Y. Academic Mobbing in Relation to Leadership Practices: A New Perspective on an Old Issue. Educ. Forum 2020, 84, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, K.N.; Smittick, A.L.; He, Y.; Costa, P.L. Organizations Behaving Badly: Antecedents and Consequences of Uncivil Workplace Environments. J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl. 2019, 153, 528–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berquist, R.; St-Pierre, I.; Holmes, D. Uncaring Nurses: An Exploration of Faculty-to-Faculty Violence in Nursing Academia. Int. J. Hum. Caring 2017, 21, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, K.; Barnes, K. Workplace Bullying Among Higher Education Faculty: A Review of the Theoretical and Empirical Literature. J. High. Educ. Theory Pract. 2021, 21, 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Goodboy, A.K.; Martin, M.M.; Mills, C.B.; Clark-Gorden, C.V. Workplace Bullying in Academia: A Conditional Process Model. Manag. Commun. Q. 2022, 36, 664–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahie, D. The lived experience of toxic leadership in Irish higher education. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2020, 13, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriläinen, M.; Käyhkö, K.; Kõiv, K.; Sinkkonen, H.M. Academic bullying among faculty personnel in Estonia and Finland. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2019, 41, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L.M.; Cortina, M.G.; Cortina, J.M. Regulating rude: Tensions between free speech and civility in academic employment. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 12, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedivy-Benton, A.; Stroheschen, G.; Cavazos, N.; Boden-McGill, C. Good Ol’ Boys, Mean Girls and Tyrants. A Phenomenological Study of the Lived Experiences and Survival Strategies of Bullied Women Adult Educators. Adult Learn. 2014, 26, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, A. Reckoning up: Sexual harassment and violence in the neoliberal university. Gend. Educ. 2020, 32, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgins, M.; Mannix McNamara, P. The Neoliberal university in Ireland: Institutional bullying by another name? Societies 2021, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, C.T. Spotlight on ethics: Institutional review boards as systemic bullies. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2015, 37, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coy, M.; Bull, A.; Libarkin, J.; Page, T. Who is the Practitioner in Faculty-Staff Sexual Misconduct Work?: Views from the UK and US. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP14996–NP15019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.; Cohen, C. Dangerous Work: The Gendered Nature of Bullying in the Context of Higher Education. Gend. Work Organ. 2004, 11, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, G.; Cheng, H. Gender and power in the ivory tower: Sexual harassment in graduate supervision in China. J. Gend. Stud. 2023, 32, 600–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eller, A. Transactional sex and sexual harassment between professors and students at an urban university in Benin. Cult. Health Sex. 2016, 18, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizardi, M.; Gonzálvez, H.; Stefoni, C. The Shoemaker and Her Barefooted Daughter: Power Relations and Gender Violence in University Contexts. Front. J. Women Stud. 2022, 43, 32–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, L.P. In the Room, but no Seat at the Table: Mixed Methods Analysis of HBCU Women Faculty and Workplace Bullying. J. Educ. 2024, 204, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, E.; Bustelo, M. Sexual and sexist harassment in Spanish universities: Policy implementation and resistances against gender equality measures. J. Gend. Stud. 2022, 31, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, A.; Ali, R. Negotiating Sexual Harassment: Experiences of Women Academic Leaders in Pakistan. J. Int. Women’s Stud. 2022, 23, 263–279. [Google Scholar]

- D’Cruz, P.; Noronoha, E. Mapping “Varieties of Workplace Bullying”: The Scope of the Field. In Concepts, Approaches and Methods; Handbooks of Workplace Bullying Emotional Abuse and Harassment Vol. 1; D’Cruz, P., Noronha, E., Notelaers, G., Rayner, C., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- D’Cruz, P. India: A paradoxical context for workplace bullying. In Workplace Abuse, Incivility and Bullying: Methodological and Cultural Perspectives; Omari, M., Paull, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, J.; O’Sullivan, M.; MacCurtain, S.; Murphy, C.; Ryan, L. “It’s not us, it’s you”: Extending Managerial Control through Coercion and Internalisation in the Context of Workplace Bullying amongst Nurses in Ireland. Societies 2021, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, B.; Krupa, G.; McCall, D. Settings for Health Promotion: An analytic Framework to Guide Intervention Design and Implementation. Health Promot. Pract. 2009, 10, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, M. Bullshit Towers; Lang: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Desierto, A.; de Maio, C. The impact of neoliberalism on academics and students in higher education: A call to adopt alternative philosophies. J. Acad. Lang. Learn. 2020, 14, 148–159. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, P. Dark Academia. How Universities Die; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Agócs, C. Institutionalized Resistance to Organizational Change: Denial, Inaction and Repression. J. Bus. Ethics 1997, 16, 917–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eylon, D. Understanding empowerment and resolving its paradox: Lessons from Mary Parker Follett. J. Manag. Hist. 1998, 4, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fevre, R.; Lewis, D.; Robinson, A.; Jones, T. Trouble at Work; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Phenomenon | AND | Population | AND | Context |

| “Sexual Harassment” | Faculty | “College of further Education” | ||

| OR | OR | OR | ||

| “Psychological aggression” | Lecturer* | “Higher Education institution” | ||

| OR | OR | OR | ||

| “Psychological violence” | Academic* | University | ||

| OR | OR | OR | ||

| Bully* | Professor* | “Tertiary education institution” | ||

| OR | OR | OR | ||

| Incivility | Staff | College | ||

| OR | ||||

| Mistreatment | ||||

| OR | ||||

| Ostracism |

| Methods Employed | Number |

|---|---|

| Prevalence (survey) | 42 |

| Intervention (e.g., before vs. after, or (q) experimental design) | 1 |

| X-sectional (e.g., correlational) | 18 |

| Mechanism, i.e., mediator/moderator analysis | 25 |

| Factor analysis | 10 |

| Outcome quantitatively measured (e.g., effects as measured by a scale) | 22 |

| Qualitative study (e.g., focus groups or interviews) * | 32 |

| Economic evaluation | 1 |

| Review (narrative, systematic, or scoping review) | 5 |

| Conceptual | 11 |

| Perceptions or attitudes towards events or policy | 21 |

| Documentary | 6 |

| Mixed methods (combined qualitative * and quantitative) | 5 |

| Testing or developing a model | 5 |

| Other § | 7 |

| Focus of Enquiry: Type of Institution | |

| Public university | 74 |

| Private university | 6 |

| University (type unstated) | 17 |

| College (e.g., community, nursing, etc.) | 6 |

| Mixed | 26 |

| Unclear | 4 |

| Not applicable | 7 |

| Focus of Enquiry: Population | |

| Faculty/academic | 76 |

| Combined students and staff | 22 |

| Professional staff (administration, library, laboratory, technical) | 16 |

| All staff (i.e., not specified) | 24 |

| Other ± | 2 |

| Students (as perpetrators sexual harassment) | 2 |

| Focus of Enquiry: Types of Ill Treatment | |

| Workplace bullying | 62 |

| Sexual harassment | 49 |

| Gender-based violence | 8 |

| Incivility | 31 |

| Institutional bullying | 1 |

| Workplace ostracism | 4 |

| Mobbing (i.e., group bullying) | 4 |

| Toxic leadership | 3 |

| Gender-based discrimination | 4 |

| Unclear | 1 |

| Focus of Enquiry: Continent and Country $ | |

| America (USA: 38; South America: 3; Canada: 4) | 45 |

| Europe (UK: 10; Estonia: 5; Sweden: 5; Finland: 3; Ireland: 4; Spain: 3; Czech Republic: 2; Italy: 2; Albania, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Lithuania, Norway: 1 each) | 40 |

| Asia (Pakistan: 7; Turkey: 7; China: 4; Malaysia: 2; Indonesia: 2; India: 2; Jordan: 2; Japan: 1; Singapore: 1; Iran: 1) | 29 |

| Africa (South Africa: 5; Botswana: 2; Nigeria: 2; Ethiopia: 2; Benin, Egypt, Zambia, and Zimbabwe: 1 each) | 15 |

| Oceania (Australia: 5; New Zealand: 1) | 6 |

| Dates of Publication | |

| 2003–2008 | 11 |

| 2009–2013 | 17 |

| 2014–2018 | 34 |

| 2019–2023 | 74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hodgins, M.; Kane, R.; Itzkovich, Y.; Fahie, D. Workplace Bullying and Harassment in Higher Education Institutions: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091173

Hodgins M, Kane R, Itzkovich Y, Fahie D. Workplace Bullying and Harassment in Higher Education Institutions: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(9):1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091173

Chicago/Turabian StyleHodgins, Margaret, Rhona Kane, Yariv Itzkovich, and Declan Fahie. 2024. "Workplace Bullying and Harassment in Higher Education Institutions: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 9: 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091173

APA StyleHodgins, M., Kane, R., Itzkovich, Y., & Fahie, D. (2024). Workplace Bullying and Harassment in Higher Education Institutions: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(9), 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091173