Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an important opportunistic pathogen in recreational waters and the primary cause of hot tub folliculitis and otitis externa. The aim of this surveillance study was to determine the background prevalence and antimicrobial resistance profile of P. aeruginosa in swimming pools and hot tubs. A convenience sample of 108 samples was obtained from three hot tubs and eight indoor swimming pools. Water and swab samples were processed using membrane filtration, followed by confirmation with polymerase chain reaction. Twenty-three samples (21%) were positive for P. aeruginosa, and 23 isolates underwent susceptibility testing using the microdilution method. Resistance was noted to several antibiotic agents, including amikacin (intermediate), aztreonam, ceftriaxone, gentamicin, imipenem, meropenem (intermediate), ticarcillin/clavulanic acid, tobramycin (intermediate), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. The results of this surveillance study indicate that 96% of P. aeruginosa isolates tested from swimming pools and hot tubs were multidrug resistant. These results may have important implications for cystic fibrosis patients and other immune-suppressed individuals, for whom infection with multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa would have greater impact. Our results underlie the importance of rigorous facility maintenance, and provide prevalence data on the occurrence of antimicrobial resistant strains of this important recreational water-associated and nosocomial pathogen.

1. Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an important Gram-negative opportunistic pathogen, is the primary cause of hot tub folliculitis, otitis externa, as well as the principal cause of morbidity and mortality in cystic fibrosis patients [1]. P. aeruginosa is highly ubiquitous in water systems, and has intrinsic antimicrobial resistance due to low outer membrane permeability, as well as an extensive efflux pump system [2–4]. Additionally, some P. aeruginosa strains exhibit mutations in fluoroquinolone binding sites, the loss of porin channels, and increased beta-lactamase or cephalosporinase production [3,4]. P. aeruginosa frequently acquires additional resistance mechanisms (i.e., from plasmids) and routinely develops multidrug resistance throughout the course of a treatment regimen [4,5]. The overall prevalence of antibiotic resistant P. aeruginosa is increasing, with up to 10% of global isolates found to be multidrug-resistant [6]. This represents a major treatment challenge, as P. aeruginosa is the second leading cause of gram-negative nosocomial infections [7].

Indoor recreational water is an important reservoir for P. aeruginosa and is a meaningful exposure pathway for bacterial transmission, where wet skin and occlusion provide optimal conditions for P. aeruginosa to thrive [8]. P. aeruginosa has been implicated in numerous nosocomial and community outbreaks, with therapy tanks and whirlpools frequently acting as the environmental reservoir [8–10]. Complex or hard to clean piping has been noted as a factor in P. aeruginosa contamination; in nosocomial and household settings, contaminated sinks and shower heads have been a common reservoir for P. aeruginosa, where the inaccessible armature is nearly impossible to adequately decontaminate [8,11]. Swimming pools and hot tubs have even more complex piping systems than sinks and showers, thus increasing the difficulty of cleaning. The temperature range in indoor recreational water is ideal for P. aeruginosa proliferation, which routinely grows in water 4–42 °C [8,12,13]. Finally, the high temperature and considerable agitation/aeration of hot tub water may cause rapid dissipation of halogen levels, thus rendering chlorine-based disinfectants ineffective [14,15].

While conditions are ideal for P. aeruginosa contamination, the background prevalence of P. aeruginosa in indoor recreational water has not been well evaluated during non-outbreak periods, where adequate chlorine levels are expected to prevent contamination [15,16]. Determining the endemicity of P. aeruginosa in indoor swimming pools and hot tubs during non-outbreak periods may have important infection control and facility maintenance implications. Our first study goal was to examine the prevalence of P. aeruginosa contamination in both of these indoor recreational waters, through the collection of water and swab samples.

The second goal of the study was to evaluate the level of antimicrobial resistance among the P. aeruginosa isolates from swimming pools and hot tubs. The presence of multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa in a recreational environment may be important for immune-suppressed or other at-risk individuals, for whom treatment difficulties have greater implications [1]. Indeed, infections with drug-resistant P. aeruginosa often result in increased cost of treatment, lengthy stay, and overall morbidity and mortality [7,17,18]. In addition, given the propensity of P. aeruginosa to proliferate rapidly when disinfectant levels fall below recommended levels, monitoring the prevalence of resistant strains may be important for the prevention of future outbreaks.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Sample Collection

A convenience sample of 50 water and 58 swab samples were obtained from eight indoor swimming pools and three hot tubs from March, 2009 through April, 2010 from throughout the central Ohio area in the United States. All swimming pools were public Class A or B competition or large recreation pools (Class A pools are large public pools intended primarily for competition; Class B pools are public recreation pools). One hot tub was a small residential model and two were public, large capacity systems. All public hot tubs and pools were operated by either an educational institution or municipality. Water samples were collected in sterile, polypropylene tubes, at approximately 0.30–0.50 meters below the water surface to best simulate an exposure zone; this depth is similar to a sampling regime recommended for beach water [19]. Sterile rayon swabs were used to collect biofilm from swimming pool and hot tub jets, strainers, and side drain locations. Swab samples were rotated (spun) both along the swab axis and moved laterally to collect an appropriate biofilm sample. All samples were transported to the laboratory on ice for immediate analysis. Aseptic technique was observed throughout sampling activities. Temperature readings were obtained while onsite using a digital thermometer.

Water samples were analyzed for free chlorine, total chlorine, and turbidity. Free and total chlorine levels were measured immediately according to DPD Method 10069 and 10070 using a Hach 2800 spectrophotometer (Hach, Loveland, CO, USA). The method reporting range is 0.1–10.0 mg/L (although >10.0 mg/L is provided by the Hach). Turbidity readings were measured using a Hach 2100P portable turbidimeter (Hach, Loveland, CO, USA).

2.2. Bacterial Isolation and Confirmation with PCR

Water samples were concentrated by membrane filtration using a sterile 0.45-μm-pore-size, 47-mm-diameter cellulose membrane filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) [19]. Swab samples were processed similarly, also using membrane filtration. In order to maximize bacterial recovery from a swab, the swab-containing tube was filled with approximately 5mL of buffer, vortexed for 10s, and the buffer passed through a 0.45-μm-pore-size, 47-mm-diameter cellulose membrane filter. All membrane filters were placed directly onto Pseudomonas Isolation Agar (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA) and incubated at 37 °C for up to 48 hours. After incubation, up to three randomly selected colonies with appropriate morphological characteristics were sub-cultured for enrichment and purification using R2A agar with 0.5% yeast extract (in order to maximize the growth of the bacteria isolated from disinfectant-treated source). R2A plates were incubated at 37 °C for up to 48 hours. R2A was used because recovered bacteria may have been injured or stressed due to the presence of chlorine, and R2A is an efficient medium for recovering bacteria from disinfectant-containing samples by providing a low concentration of diverse nutrients [20]. In previous work, we modified this method by adding a low concentration of yeast extract, which showed good recovery of bacterial isolates from potable water [21]. Up to three isolates were obtained from purified, suspected P. aeruginosa samples, and confirmed using polymerase chain reaction (end-point and real time qPCR). Negative and positive controls (ATCC 27853) were utilized for all reactions. All end-point PCR was conducted using a MultiGene Thermal Cycler (Labnet International Inc., Edison, NJ, USA), under the following conditions: 95 ºC for 1 min; 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 ºC for 15 s, annealing at 58 ºC for 20 s; final extension at 68 ºC for 40 s; with primer pa722F (5′-GGCGTGGGTGTGGAAGTC-3′) and pa899R (5′-TGGTGGCGATCTTGAAC TTCTT-3′). For the real-time PCR, we used ABI Pseudomonas detection kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with a 48-well StepOne™ Real Time System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) to 22 antimicrobial agents was determined using a TREK Sensititre Sensitouch microdilution system (TREK, Cleveland, OH, USA). Twenty-three randomly selected isolates (at least one per P. aeruginosa-positive sample) were chosen for analysis and processed according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol and the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute methods [22]. The 23 screened isolates represent 20 of the 23 total P. aeruginosa-positive samples; isolates from three samples failed to be subcultured sufficiently for microdilution analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

A total of 108 water (swimming pool samples n = 41; hot tub samples n = 17) and swab samples (swimming pool samples n = 36; hot tub samples n = 14) were collected from eight swimming pools and three hot tubs. Twenty-three samples (21%) were positive for P. aeruginosa, of which 16 were from hot tubs (70%); all samples from the residential hot tub were positive. Sixty-seven percent (2/3) of hot tubs and 63% (5/8) of swimming pools were positive at least once for P. aeruginosa. P. aeruginosa-positive samples were much more likely to come from swabs than from water samples. The positive swab locations were diverse, including side-wall tiles, gutter drains, jets, and strainer baskets which may indicate that these are biofilm-rich locations. Table 1 shows the prevalence data.

Table 1.

Prevalence of P. aeruginosa in hot tubs and swimming pools.

Water analysis indicated low turbidity overall (0.1–0.6 NTUs), and a wide range of free (FC) and total chlorine (TC) levels (FC: 0.8 to >10.0 mg/L, average 8.46 mg/L; TC: 1.0 to >10.0 mg/L, average >10 mg/L). Swimming pool temperature ranged from 25.9 °C to 32.4 °C, and hot tub temperature 38.7 °C to 39.3 °C. Differences were noted between P. aeruginosa-positive and negative samples with respect to water temperature and free chlorine. Turbidity levels were very similar between the groups. Water quality data were not available for the residential hot tub (which comprised 63% of the P. aeruginosa positive hot tub samples).

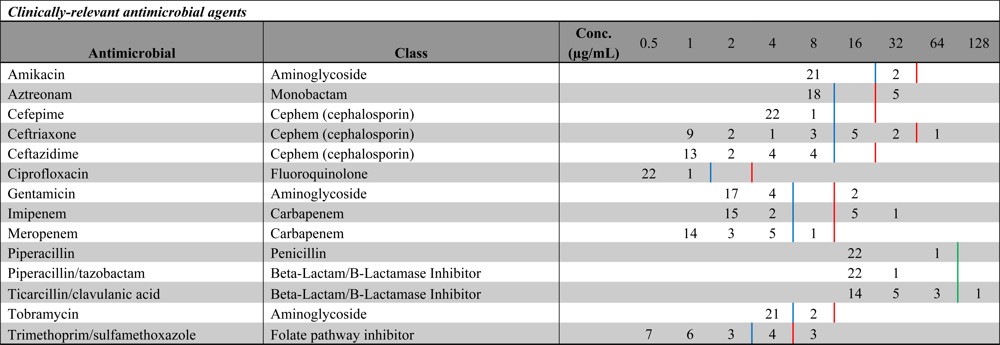

All 23 isolates analyzed were resistant to at least one antimicrobial, and several were multidrug-resistant. Of the clinically relevant antibiotics included in the screening panel, there was resistance to amikacin (intermediate, 9%), aztreonam (22%), ceftriaxone (4% resistant, 30% intermediate), gentamicin (9%), imipenem (26%), meropenem (intermediate, 4%), ticarcillin/clavulanic acid (4%), tobramycin (intermediate, 9%), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (13% resistant, 17% intermediate). Table 2 shows minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) to these antibiotics. High levels of resistance were noted to eight additional antibiotics (e.g., ampicillin, nitrofurantoin, etc.; See Table 3), but these were not included in the MIC analysis as they are not clinically indicated for the treatment Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Resistance is defined as an MIC result above the susceptibility upper bound, and intermediate resistance is defined as an MIC result above the susceptibility lower bound, but below the susceptibility upper bound.

Table 2.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) to 14 clinically-relevant antimicrobial agents for P. aeruginosa. Blue lines represent susceptibility lower bound and red lines represent susceptibility upper bound. Green lines indicate no intermediate susceptibility breakpoint zone.

Table 3.

Percentage of resistance of P. aeruginosa isolates to eight additional antimicrobial agents.

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that P. aeruginosa contamination is common in swimming pools and hot tubs, even where chlorine concentrations are well above recommended levels. Recommendations for adequate chlorine levels are 2 to 4 mg/L for swimming pools, and 3 to 5 mg/L for hot tubs, measured as free chlorine [23]. According to NSPF recommendations, facilities should consider immediate closure when free chlorine levels fall below 1 mg/L, because contamination can quickly reach unsafe concentrations. With regard to hot tubs, prior research has demonstrated that even when hot tubs are drained, cleaned, and refilled, P. aeruginosa may return with a level of 104–106 cells/mL within 24 to 48 hours when adequate chlorine levels are not maintained [15]. In the current study, chlorine concentrations were higher than in past studies; and while P. aeruginosa was routinely isolated, the regularly high chlorine levels found here likely reduced prevalence. This confirms the importance of not only adequate disinfectant levels, but also constant monitoring and adjustment to ensure chlorine levels never drop below recommended levels. It should be noted that the facilities in this study conducted hourly monitoring of pool and hot tub chlorine concentrations, except the residence, which performed weekly monitoring. The less frequent monitoring of the residential hot tub may have resulted in greater halogen fluctuations, and thus higher prevalence of P. aeruginosa.

Consistent with previous research, a relationship between high chlorine levels, biofilm growth (as indicated by swab samples, which contain higher levels of biofilm-embedded bacteria, versus water samples, which are more likely to represent planktonic bacteria), and the presence of P. aeruginosa, was noted. LeChevallier et al. (1988) have described several mechanisms leading to disinfectant resistance, of which attachment to surfaces was most important [24]. They note that low-nutrient environments enhanced free chlorine resistance by two to three times. Thus, it is not surprising that this study indicated higher prevalence of P. aeruginosa in pools/hot tubs with higher chlorine levels. There was also a relationship between higher water temperature and the presence of P. aeruginosa. This finding is consistent with the thermo-tolerant nature of P. aeruginosa.

There are several possible reasons why P. aeruginosa was more likely to be isolated from hot tubs over swimming pools. Hot tub piping systems are complex and inaccessible for cleaning; this complexity may enhance biofilm formation [9]. In addition, hot tub capacity is lower (per bather) than swimming pools (0.757 m3/person for a hot tub versus 6.81 m3/person for swimming pools); this may act to concentrate microbial load present in the water [23]. Finally, high pressure jets are an integral component of hot tubs, with bathers often using jets to enhance relaxation. Contact with jets in this manner may enhance sloughing of skin squames, further fouling hot tub piping systems.

The results of this study also indicated that environmental P. aeruginosa has considerable levels of antibiotic resistance. Isolates demonstrated resistance to a wide range of clinically relevant antimicrobial agents, including antipseudomonal agents aztreonam (22%), gentamicin (9%), and imipenem (26%); and intermediate resistance to amikacin (9%), meropenem (4%), and tobramycin (9%). Resistance was also noted to alternate agents ceftriaxone (4% resistant, 30% intermediate), ticarcillin/clavulanic acid (4%), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (13% resistant, 17% intermediate). Although P. aeruginosa is a model of antimicrobial resistance (due to a number of intrinsic factors), past research has found that the degree of resistance to antipseudomonal agents varies considerably. The current results are similar to past studies, which have found analogous prevalence levels of resistant P. aeruginosa in both the hospital and community [4,10].

The origins of multidrug-resistant strains in the swimming pool and hot tub environment are unknown, but may have developed through several mechanisms. Since P. aeruginosa is intrinsically resistant, it is possible that the frequency with which we isolated resistant P. aeruginosa is representative of natural background levels. Alternately, in some cases resistant P. aeruginosa strains may ultimately be traced to a human source, either direct shedding from colonized humans or indirect transmission through the contamination in upstream aquatic reservoir. P. aeruginosa is not a predominant component of normal human flora (colonization rates are low: up to 2% on the skin and to 24% in fecal matter) [4,25]. However, during hospitalization, colonization rate may reach 50% [4,25]. Also, immune suppressed individuals or those whom have recently undergone antimicrobial treatment may have higher colonization rates [4,25,26]. In addition, in clinical settings, there is a strong relationship between the P. aeruginosa strains which infect patients and those in the immediate patient environment. Rogues et al. [27] pointed-out that carriage of P. aeruginosa by patients was “both the source and the consequence of (tap) water colonization”. That is, a colonized or infected patient may lead to in-room and neighboring area contamination; and contaminated water, fomites, and aerosols may infect susceptible individuals [27]. A similar phenomenon may occur in recreational water, particularly if frequented by colonized or infected individuals.

In some cases, there may be selective pressure for resistance by the presence of low-level antibiotic concentrations in either sweat secretions, which may enter recreational water through bather use, or from supply water. Prior research has demonstrated the presence of a range of antimicrobial agents in arm and axilla sweat secretions after oral or intravenous dosing [28]. While isolated concentrations were found to be quite low, this is a possible mechanism for the development of resistant strains. Antibiotics have also been routinely isolated in water at various stages of processing, including in post-chlorination drinking water [29]. Importantly, in some cases chlorinated water was found to select for more multidrug-resistant strains over non-chlorinated water [30]. Given that the swimming pool and hot tub supply water in our study begins as municipal drinking water but then becomes highly chlorinated to reach disinfection levels, there may be enhanced selection for resistant strains.

While the levels of resistance among study isolates are similar to those previously reported, it is important to draw the distinction between a nosocomial setting and the non-clinical, non-outbreak, recreational setting of the current study. In clinical scenarios, there is constant selective pressure to enhance the proliferation of multidrug-resistant strains. Given that P. aeruginosa has both intrinsic resistance and a dynamic ability to develop resistance during the course of infection, a high frequency of resistance is now expected in hospitals. However, in the non-clinical environment, the absence of selective pressure may reduce antimicrobial resistance levels. The presence of resistance to front-line antipseudomonal drugs may have important clinical and prevention implications. Given how common swimming pool and hot tub use is, immune-suppressed or other high-risk individuals may wish to exercise caution before use, especially hot tub use. Exposure to resistant P. aeruginosa results in even greater risk for individuals with cystic fibrosis.

Study limitations include a relatively small sample size and the convenience design. Although only one residential hot tub was accessible for sampling in this study, there was a desire to broadly evaluate whether differences existed in the prevalence of P. aeruginosa and the degree of antimicrobial resistance. The residential hot tub owner did not experience previous skin diseases related to the hot tub and the hot tub did not undergo thorough maintenance and flush-fill cycles as did the public hot tubs, which were cleaned daily, drained completely once per week, and have fresh water introduced continually. Further study is required with expanded sample size to determine if the frequency of multidrug-resistant strains remains steady over time. Additional studies should focus primarily on hot tubs, where 53% of samples were positive. Also, isolates from three P. aeruginosa-positive samples were unable to be revived for antimicrobial resistance analysis.

4. Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that Pseudomonas aeruginosa can be regularly isolated from both swimming pools and hot tubs, with substantial prevalence. In addition, isolated P. aeruginosa is resistant to a wide variety of antimicrobial agents, including front-line antipseudomonal drugs. These results are despite the high disinfectant levels noted in water samples. We believe that these findings underlie the critical importance of regular, thorough, aggressive maintenance to ensure a clean, healthy swimming pool and hot tub environment. The results confirm that high chlorine levels are not alone sufficient to prevent P. aeruginosa growth, and that notable levels of antimicrobial resistant P. aeruginosa are endemic in both hot tubs and swimming pools.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially funded through a grant from the Center for Clinical and Translational Science/Public Health Preparedness for Infectious Disease at the Ohio State University. We wish to thank Thomas Wittum and Dixie Mollenkopf, for the use and assistance with the Sensititre system. In addition, we greatly appreciate the laboratory assistance of Chang Soo Lee, and the access and support of the swimming pool and hot tub facility managers.

References and Notes

- Bodey, GP; Bolivar, R; Fainstein, V; Jadeja, L. Infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Rev. Infect. Dis 2008, 5, 279–313. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, K; Iwai, S; Kumasaka, K; Horikoshi, A; Inada, S; Inamatsu, T; Ono, Y; Nishiya, H; Hanatani, Y; Narita, T; Sekino, H; Hayashi, I. Survey of antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by the Tokyo Johoku Association of Pseudomonas Studies. J. Infect. Chemother 2001, 7, 258–262. [Google Scholar]

- Aeschlimann, J. The role of multidrug efflux pumps in the antibiotic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacteria. Pharmacotherapy 2003, 23, 916–924. [Google Scholar]

- Lister, PD; Wolter, DJ; Hanson, ND. Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2009, 22, 582–610. [Google Scholar]

- Strateva, T; Yordanov, D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa—A phenomenon of bacterial resistance. J. Med. Microbiol 2009, 58, 1133–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Gales, AC; Jones, RN; Turnidge, J; Rennie, R; Ramphal, R. Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates: occurrence rates, antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, and molecular typing in the global SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997–1999. Clin. Infect. Dis 2001, 32, S146–S155. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, Y; Troillet, N; Karchmer, AW; Samore, MH. Health and economic outcomes of antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Arch. Intern. Med 1999, 159, 1127–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Zichichi, L; Asta, G; Noto, G. Pseudomonas aeruginosa folliculitis after shower/bath exposure. Int. J. Dermatol 2000, 39, 270–273. [Google Scholar]

- Berrouane, YF; McNutt, LA; Buschelman, BJ; Rhomberg, PR; Sanford, MD; Hollis, RJ; Pfaller, MA; Herwaldt, LA. Outbreak of severe Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections caused by a contaminated drain in a whirlpool bathtub. Clin. Infect. Dis 2000, 31, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai-Komada, N; Hirano, M; Nagata, I; Ejima, Y; Nakamura, M; Koike, KA. Risk of transmission of imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa through use of mobile bathing service. Environ. Health Prev. Med 2006, 11, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, S; Sigge, A; Wiedeck, H; Trautmann, M. Analysis of transmission pathways of Pseudomonas aeruginosa between patients and tap water outlets. Crit. Care Med 2002, 30, 2222–2228. [Google Scholar]

- Blondel-Hill, E; Henry, DA; Speert, DP. Pseudomonas. In Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 9th ed; Murray, PR, Baron, EJ, Jorgensen, JH, Landry, ML, Pfaller, MA, Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 734–748. [Google Scholar]

- Dulabon, LM; LaSpina, M; Riddell, SW; Kiska, DL; Cynamon, M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa acute prostatitis and urosepsis after sexual relations in a hot tub. J. Clin. Microbiol 2009, 47, 1607–1608. [Google Scholar]

- Muraca, P; Stout, JE; Yu, VL. Comparative assessment of chlorine, heat, ozone, and UV light for killing Legionella pneumophila within a model plumbing system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 1987, 53, 447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Price, D; Ahearn, DG. Incidence and persistence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in whirlpools. J. Clin. Microbiol 1988, 26, 1650–1654. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, CF; Smith, PG. The survival of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during bromination in a model whirlpool spa. Lett. Appl. Microbiol 1992, 14, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Aloush, V; Navon-Venezia, S; Seigman-Igra, Y; Cabili, S; Carmeli, Y. Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: risk factors and clinical impact. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2006, 50, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gasink, LB; Fishman, NO; Weiner, MG; Nachamkin, I; Bilker, WB; Lautenbach, E. Fluoroquinolone-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: assessment of risk factors and clinical impact. Am J Med 2006, 119, 526e19–526e25. [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association; American Water Works Association; Water Environmental Federation. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 18th ed; American Public Health Association: New York, NY, USA, 1992; Section 9213,; pp. 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Reasoner, DJ; Geldreich, EE. A new medium for the enumeration and subculture of bacteria from potable water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 1985, 49, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J; Lee, CS; Hugunin, KM; Maute, CJ; Dysko, RC. Bacteria in drinking water supply and their fate in gastrointestinal tracts of germ-free mice: a phylogenetic comparison study. Water Res 2010, 44, 5050–5058. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; eighteenth informational supplement (document M100-S18); The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- NSPF Pool and Spa Operator Handbook; National Swimming Pool Foundation: Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2007.

- LeChevallier, MW; Cawthon, CD; Lee, RG; Lechevallier, MW; Cawthon, CD; Lee, RG. Factors promoting survival of bacteria in chlorinated water supplies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 1988, 54, 649–654. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, AJ; Wenzel, RP. Epidemiology of infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Rev. Infect. Dis 1984, 6, S627–S642. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In Principles and Practices of Infectious Diseases; Mandell, GL, Dolan, R, Bennett, JE, Eds.; Churchill Livingstone: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 1820–2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rogues, AM; Boulestreau, H; Lashéras, A; Boyer, A; Gruson, D; Merle, C; Castaing, Y; Bébear, CM; Gachie, JP. Contribution of tap water to patient colonisation with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a medical intensive care unit. J. Hosp. Infect 2007, 67, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hoiby, N; Pers, C; Johansen, HK; Hansen, H. Excretion of beta-lactam antibiotics in sweat—A neglected mechanism for development of antibiotic resistance? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2000, 44, 2855–2857. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Z; Weinberg, HS; Meyer, MT. Trace analysis of trimethoprim and sulfonamide, macrolide, quinolone, and tetracycline antibiotics in chlorinated drinking water using liquid chromatography electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem 2007, 79, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, GE; Tobin, RS; Junkins, B; Kushner, DJ. Effect of chlorination on antibiotic resistance profiles of sewage-related bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 1984, 48, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).