Feasibility Randomised Control Trial of OptiMal: A Self-Management Intervention for Cancer Survivors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Intervention

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Data Collection

2.5.1. Primary Outcomes

2.5.2. Secondary Outcomes

3. Data Analysis

4. Results

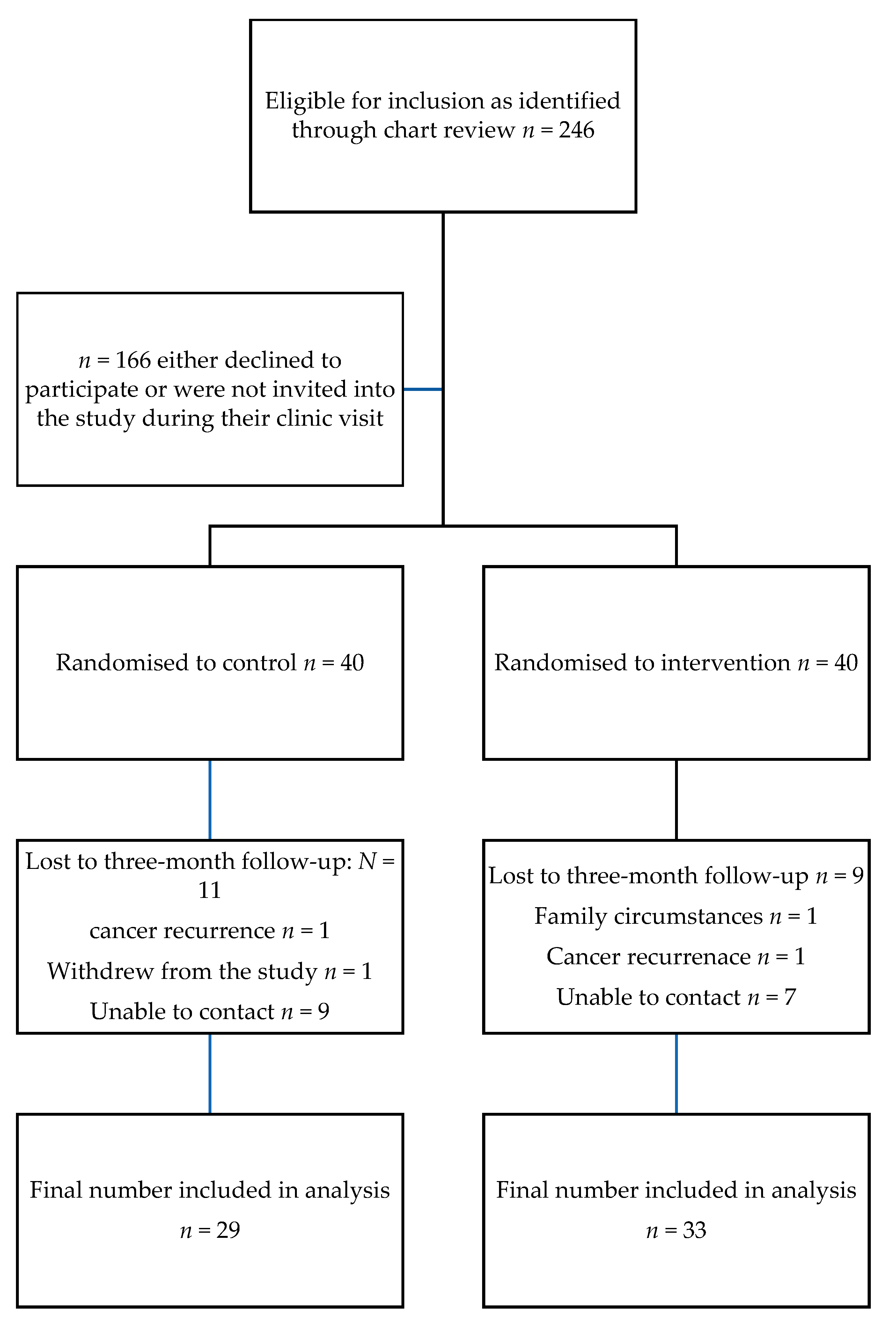

4.1. Recruitment and Retention

4.2. Adherence to Intervention

4.3. Fidelity of Intervention Delivery

4.4. Comparison of Secondary Outcomes between Control and Intervention Participants

5. Discussion

Feasibility

6. Potential Effectiveness

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Department of Health. National Cancer Strategy 2017–2026. Department of Health, Dublin. 2017. Available online: https://assets.gov.ie/9315/6f1592a09583421baa87de3a7e9cb619.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Stark, L.L.P.; Tofthagen, C.P.; Visovsky, C.P.; McMillan, S.C.P. The Symptom Experience of Patients With Cancer. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2012, 14, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; Fenlon, D. Recovery and self-management support following primary cancer treatment. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 105, S21–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.; Wright, C.; Sheasby, J.; Turner, A.; Hainsworth, J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: A review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2002, 48, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.R.; Holman, H.R. Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2003, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, M.; Greenfield, S.; Stovall, E. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivors: Lost in Transition; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boland, L.; Bennett, K.; Connolly, D. Self-management interventions for cancer survivors: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 1585–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, C.A.; Farragher, J.F.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Ding, Q.; McKinnon, G.P.; Cheung, W.Y. Self-management interventions for cancer survivors: A systematic review and evaluation of intervention content and theories. Psycho-Oncol. 2019, 28, 2119–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toole, L.O.; Connolly, D.; Smith, S. Impact of an occupation-based self-management programme on chronic disease management. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2013, 60, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, J.; Connolly, D.; Boland, F.; Smith, S.M. OPTIMAL, an occupational therapy led self-management support programme for people with multimorbidity in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam. Pr. 2015, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.R. Goal Setting and Action Planning for Health Behavior Change. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2017, 13, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCorkle, R.; Ercolano, E.; Lazenby, M.; Schulman-Green, D.; Schilling, L.S.; Lorig, K.; Wagner, E.H. Self-management: Enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, S.M.; Chan, C.L.; Campbell, M.J.; Bond, C.M.; Hopewell, S.; Thabane, L.; Lancaster, G.A. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016, 355, i5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingham, S.A.; Whitehead, A.L.; Julious, S.A. An audit of sample sizes for pilot and feasibility trials being undertaken in the United Kingdom registered in the United Kingdom Clinical Research Network database. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, L.M.; Furberg, C.D.; DeMets, D.L. Fundamentals of Clinical Trials, 3rd ed.; Mosby-Year Book, Inc.: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Boland, L.; Bennett, K.; Cuffe, S.; Gleeson, N.; Grant, C.; Kennedy, J.; Connolly, D. Cancer survivors’ experience of OptiMal, a 6-week, occupation-based, self-management intervention. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 82, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.; Skilbeck, C.E. An activities index for use with stroke patients. Age Ageing 1983, 12, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.; Baptiste, S.; Carswell, A.; McColl, M.A.; Polatajko, H.; Pollock, N. Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), 3rd ed.; CAOT Publications: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, D.T.; Legh-Smith, J.; Langton Hewer, R. Social activities after stroke: Measurement and natural history using the Frenchay Activities Index. Int. Rehabilit. Med. 1985, 7, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carswell, A.; McColl, M.A.; Baptiste, S.; Law, M.; Polatajko, H.; Pollock, N. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: A research and clinical literature review. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2004, 7, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl-Jacobsen, L.; Hansen, D.G.; Wæhrens, E.E.; la Cour, K.; Søndergaard, J. Performance of activities of daily living among hospitalized cancer patients. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 22, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, K.; Cella, D.; Yost, K. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System: Properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yellen, S.B.; Cella, D.F.; Webster, K.; Blendowski, C.; Kaplan, E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the functional assessment of cancer therapy (FACT-F) Measurement System. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 1997, 13, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olssøn, I.; Mykletun, A.; Dahl, A.A. The hospital anxiety and depression rating scale: A cross-sectional study of psychometrics and case finding abilities in general practice. BMC Psychiatry 2005, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, D.E.; Cooper, P.F.; FitzGerald, P.; Parkes, K.R. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1982, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidi, A.; Christensen, S.; Mehlsen, M.; Jensen, A.B.; Pedersen, A.D.; Zachariae, R. Long-term subjective cognitive functioning following adjuvant systemic treatment: 7–9 years follow-up of a nationwide cohort of women treated for primary breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 113, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ahles, T.A.; Root, J.C.; Ryan, E.L. Cancer- and Cancer Treatment–Associated Cognitive Change: An Update on the State of the Science. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 3675–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.; Stewart, A.; Ritter, P.; Gonzalez, V.; Laurent, D.; Lynch, J. Outcome Measures for Health Education and Other Health Care Interventions; SAGE Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, C.; Breckons, M.; Cotterell, P.; Barbosa, D.; Calman, L.; Corner, J.; Fenlon, D.; Foster, R.; Grimmett, C.; Richardson, A.; et al. Cancer survivors’ self-efficacy to self-manage in the year following primary treatment. J. Cancer Surviv. 2015, 9, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EuroQol Group. EuroQol—A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990, 16, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.F.; Pickard, A.S.; Golicki, D.; Gudex, C.; Niewada, M.; Scalone, L.; Swinburn, P.; Busschbach, J. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: A multi-country study. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallingberg, B.; Turley, R.; Segrott, J.; Wight, D.; Craig, P.; Moore, L.; Murphy, S.; Robling, M.; Simpson, S.A.; Moore, G. Exploratory studies to decide whether and how to proceed with full-scale evaluations of public health interventions: A systematic review of guidance. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018, 4, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, S.A.; O’Connor, L.; McGee, A.; Kilcoyne, A.Q.; Connolly, A.; Mockler, D.; Guinan, E.; O’Neill, L. Recruitment rates and strategies in exercise trials in cancer survivorship: A systematic review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2023; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treweek, S.; Pitkethly, M.; Cook, J.; Fraser, C.; Mitchell, E.; Sullivan, F.; Jackson, C.; Taskila, T.K.; Gardner, H. Strategies to improve recruitment to randomised trials. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2, MR000013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brueton, V.C.; Tierney, J.F.; Stenning, S.; Meredith, S.; Harding, S.; Nazareth, I.; Rait, G. Strategies to improve retention in randomised trials: A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e003821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; Mols, F.; Vingerhoets, A.J.J.M.; Voogd, A.C.; Roumen, R.M.H.; Coebergh, J.W.W. Increased health care utilisation among 10-year breast cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2006, 14, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, E.; Algeo, N.; Connolly, D. Feasibility of OptiMaL, a Self-Management Programme for Oesophageal Cancer Survivors. Cancer Control. 2023, 30, 10732748231185002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdas, P.; Darwin, Z.; Kidd, L.; Blickem, C.; McPherson, K.; Hunt, K.; Bower, P.; Gilbody, S.; Richardson, G. The accessibility and acceptability of self-management support interventions for men with long term conditions: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abshire, M.; Dinglas, V.D.; Cajita, M.I.A.; Eakin, M.N.; Needham, D.M.; Himmelfarb, C.D. Participant retention practices in longitudinal clinical research studies with high retention rates. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2017, 17, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad, M.; Afshari, M.; Kazilan, F. Family support in cancer survivorship. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2011, 12, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar]

- Deimling, G.T.; Bowman, K.F.; Sterns, S.; Wagner, L.J.; Kahana, B. Cancer-related health worries and psychological distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncol. 2006, 15, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, V.; Koch-Gallenkamp, L.; Jansen, L.; Bertram, H.; Eberle, A.; Holleczek, B.; Schmid-Höpfner, S.; Waldmann, A.; Zeissig, S.R.; Brenner, H. Quality of life in long-term and very long-term cancer survivors versus population controls in Germany. Acta Oncol. 2017, 56, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, A.S.; Neary, M.P.; Cella, D. Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, A.; Howell, D. The experience of breast cancer survivors’ participation in important activities during and after treatments. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 80, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Kuo, Y.; Tai, W.; Liu, H. Exercise effects on fatigue in breast cancer survivors after treatments: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2022, 28, e12989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Weekly Session 2.5 h/Session | Content | Facilitator/s |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Introduction to OptiMal Principles of self-management Introduction to SMART goal setting | Occupational Therapist |

| Week 2 | Cancer-Related Fatigue (CRF) Causes of CRF and factors that exacerbate CRF Fatigue management strategies Weekly goal setting | Occupational Therapist |

| Week 3 | Exercise and Physical Activity Role of physical activity in recovery from cancer treatment Benefits of physical activity Recommendations for physical activity in cancer survivorship Weekly goal setting and review | Physiotherapist and Occupational Therapist |

| Week 4 | Mental Health and Cancer-related Cognitive Impairments Factors that impact on mental health Strategies for optimising mental health Cancer-related cognitive impairments Cognitive-based strategies for management of cancer-related cognitive impairments Weekly goal setting and review | Occupational Therapist |

| Week 5 | Healthy Eating Benefits of balanced diet post-treatment Integrating healthy eating habits into daily routines Weekly goal setting and review | Dietician and Occupational Therapist |

| Week 6 | Effective Communication Barriers to, and facilitators of, communicating with health professionals, employers and family members Weekly goal review | Occupational Therapist |

| Control Group (n = 40) | Intervention Group (n = 40) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 50.4 (11.75) | 51.68 (11.73) | 0.48 |

| Gender | 0.69 | ||

| Male n (%) | 3 (7.5%) | 4 (10%) | |

| Female n (%) | 37 (92.5%) | 36 (90%) | |

| Type of Cancer | 0.61 | ||

| Breast n (%) | 30 (75%) | 28 (70%) | |

| Other n (%) | 10 (25%) | 12 (30%) | |

| Type of Treatment | 0.98 | ||

| Surgery, Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy n (%) | 21 (52.5%) | 20 (50%) | |

| Other n (%) | 19 (47.5%) | 20 (50%) | |

| Time since treatment completion | 0.96 | ||

| <12 months: n (%) | 14 (35%) | 12 (30%) | |

| 12–24 months: n (%) | 26 (65%) | 28 (70%) | |

| Marital Status | 0.36 | ||

| Married n (%) | 20 (50%) | 24 (60%) | |

| Other n (%) | 20 (50%) | 16 (40%) | |

| Living Situation | 0.49 | ||

| Family n (%) | 34 (85%) | 36 (90%) | |

| Other n (%) | 6 (15%) | 4 (10%) | |

| Level of Education | 0.49 | ||

| Primary-Leaving Cert n (%) | 21 (52.5%) | 24 (60%) | |

| College/University n (%) | 19 (47.5%) | 16 (40%) | |

| Chronic Condition (Self-reported) | 0.17 | ||

| Yes n (%) | 13 (32.5%) | 19 (47.5%) | |

| No n (%) | 27 (67.5%) | 21 (52.5%) | |

| Employment Status Prior to Treatment | 0.63 | ||

| Full-time n (%) | 18 (45%) | 18 (45%) | |

| Part-time n (%) | 6 (15%) | 9 (22.5%) | |

| Other (n, %) | 16 (40%) | 13 (32.5%) | |

| Employment Status After Treatment | 0.17 | ||

| Full-time n (%) | 10 (25%) | 9 (22.5%) | |

| Part-time n (%) | 6 (15%) | 13 (32.5%) | |

| Other n (%) | 24 (60%) | 8 (20%) |

| Control Group (n = 29) | Intervention Group (n = 33) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures (Score Range) | Baseline Mean (SD) | Three-Month Follow-Up Mean (SD) | Mean Change (SD) | Baseline Mean (SD) | Three-Month Follow-Up Mean (SD) | Mean Change (SD) | Effect Size | (t-Statistic) p-Value |

| FAI 1 (0–45) | 33.3 (5.94) | 35.3 (3.44) | 2.07 (4.0) | 34.1 (5.46) | 35.9 (4.33) | 1.97 (3.6) | −0.06 | (0.99) 0.89 |

| HADS-A 2 (0–21) | 7.66 (4.58) | 8.00 (4.80) | 0.34 (2.7) | 9.21 (3.70) | 7.76 (3.23) | −1.45 (3.9) | −0.52 | (2.05) * 0.04 |

| HADS-D 3 (0–21) | 5.34 (3.50) | 5.31 (4.18) | −0.07 (3.04) | 4.97 (3.21) | 4.48 (3.33) | −0.49 (3.7) | −0.12 | (0.47) 0.61 |

| SES 4 (1–10) | 7.08 (1.54) | 7.38 (1.62) | 0.30 (1.2) | 6.93 (1.71) | 7.75 (1.85) | 0.87 (1.9) | 0.24 | (−1.37) 0.22 |

| FACIT-F 5 (0–52) | 31.72 (12.75) | 32.14 (11.59) | 0.48 (6.4) | 33.18 (10.71) | 35.67 (10.44) | 2.48 (8.3) | 0.27 | (−1.05) 0.28 |

| COPM-S 6 (1–10) | 3.52 (2.77) | 5.69 (2.43) | 2.2 (2.6) | 3.76 (2.12) | 6.36 (2.32) | 2.6 (2.2) | 0.17 | (−0.64) 0.52 |

| Control Group (n = 29) | Intervention Group (n = 33) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures (Score Range) | Baseline Median (IQR) | Three-Month Follow-Up Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) Change Score | Baseline Median (IQR) | Three-Month Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) Change Score | (z-Score) p-Value |

| EQ-5D-3L Health Index score (0–1) | 0.73 (0.1) | 0.73 (0.2) | 0 (−0.2) | 0.68 (0.1) | 0.75 (0.2) | 0.07 (−0.20) | (−3.3) 0.001 * |

| EQ-5D-3L VAS | 67.5 (31.25) | 70 (30) | 0 (−5.00) | 70 (12.5) | 75 (15) | 4.18 (14.9) | (−2.1) 0.035 * |

| COPM-P 1 (1–10) | 5 (2.6) | 6 (2.4) | 1.2 (3.0) | 5 (1.5) | 7 (2.4) | 2 (2.3) | (−0.42) 0.41 |

| CFQ 2 (0–100) | 34 (22) | 39 (24) | 1 (7.5) | 40 (28) | 39 (24) | −1.0 (1.0) | (−1.1) 0.26 |

| EQ-5D Outcomes | Control Group | Intervention Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 29) (%) | 3-month follow-up (n = 29) (%) | Baseline (n = 33) (%) | 3-month follow-up (n = 33) (%) | |

| Mobility | ||||

| No Problems | 23 (79.3%) | 17 (58.6%) | 20 (60.6%) | 24 (72.7%) |

| Moderate/Severe Problems | 6 (20.7%) | 12 (41.4%) | 13 (29.4%) | 9 (27.3%) |

| Self-Care | ||||

| No Problems | 29 (100%) | 29 (100%) | 33 (100%) | 33 (100%) |

| Usual Activities | ||||

| No Problems | 15 (51.7%) | 18 (62.1%) | 14 (42.4%) | 21 (63.6%) |

| Moderate/Severe Problems | 14 (48.3%) | 11 (37.9%) | 19 (57.6%) | 12 (36.4%) |

| Pain/Discomfort | ||||

| No Problems | 9 (31%) | 9 (31%) | 7 (21.2%) | 13 (39.4%) |

| Moderate/Severe Problems | 20 (69%) | 20 (69%) | 26 (78.8%) | 20 (60.6%) |

| Anxiety/Depression | ||||

| No Problems | 14 (48.3%) | 14 (48.3%) | 7 (21.2%) | 13 (39.4%) |

| Moderate/Severe Problems | 15 (51.7%) | 15 (51.7%) | 26 (78.8%) | 20 (60.6%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boland, L.; Bennett, K.E.; Cuffe, S.; Grant, C.; Kennedy, M.J.; Connolly, D. Feasibility Randomised Control Trial of OptiMal: A Self-Management Intervention for Cancer Survivors. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 10195-10210. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30120742

Boland L, Bennett KE, Cuffe S, Grant C, Kennedy MJ, Connolly D. Feasibility Randomised Control Trial of OptiMal: A Self-Management Intervention for Cancer Survivors. Current Oncology. 2023; 30(12):10195-10210. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30120742

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoland, Lauren, Kathleen E. Bennett, Sinead Cuffe, Cliona Grant, M. John Kennedy, and Deirdre Connolly. 2023. "Feasibility Randomised Control Trial of OptiMal: A Self-Management Intervention for Cancer Survivors" Current Oncology 30, no. 12: 10195-10210. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30120742

APA StyleBoland, L., Bennett, K. E., Cuffe, S., Grant, C., Kennedy, M. J., & Connolly, D. (2023). Feasibility Randomised Control Trial of OptiMal: A Self-Management Intervention for Cancer Survivors. Current Oncology, 30(12), 10195-10210. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30120742