Application of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) to Prioritize Real-World Evidence Studies for Health Technology Management: Outcomes and Lessons Learned by the Canadian Real-World Evidence for Value of Cancer Drugs (CanREValue) Collaboration

Abstract

:1. Introduction

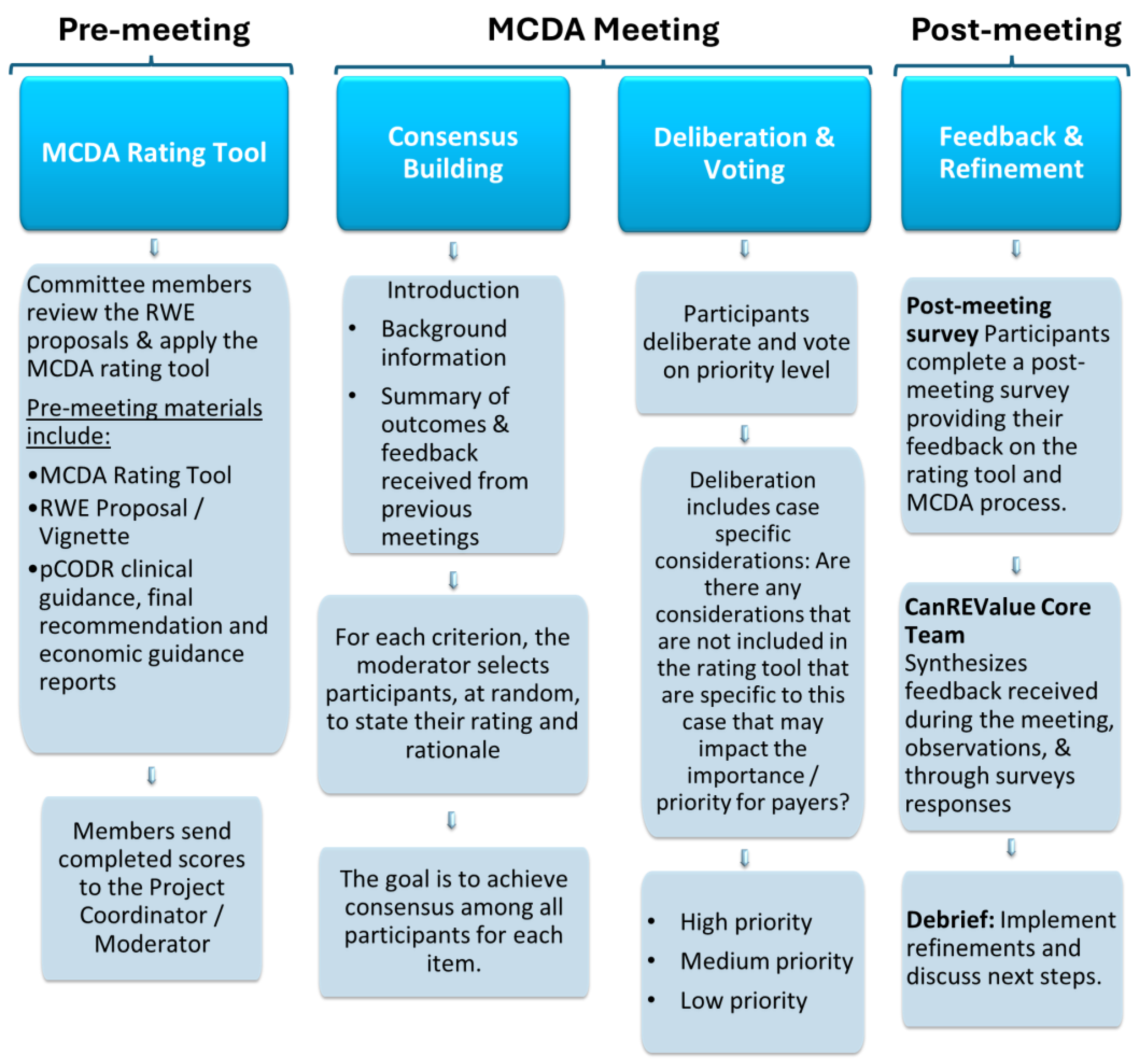

2. MCDA Validation Exercise: Approach

2.1. Development of the MCDA Rating Tool

2.2. Composition of the MCDA Committee

2.3. Format and Procedures for the MCDA Process

2.3.1. Meeting Frequency and Duration

2.3.2. Selection of Potential RWE Proposals

2.3.3. Meeting Materials and Instructions

2.3.4. MCDA Process: Consensus Building and Deliberation

2.3.5. Feedback and Tool Refinement

3. MCDA Validation Exercise: Findings

4. MCDA Rating Tool: Observations, Feedback, and Lessons Learned

4.1. Alignment between Criterion Name and Description

4.2. Improving Clarity on Criterion Instructions and Rating Descriptions

4.3. Inconsistent Interpretation

Initial instructions for Criterion 3: “The objective of this criterion is to assess the relevance of resolving the uncertainty to decision-makers (i.e., what is the likelihood that resolving uncertainty with the findings from the proposed RWE study will alter the funding status or clinical treatment recommendations).”

Revised instructions for Criterion 3: “The objective of this criterion is to assess the relevance of resolving the uncertainty to decision-makers. Specifically, users are asked to provide a qualitative assessment on whether the data generated from the proposed RWE study could lead to future policy change (i.e., price re-negotiation, change in funding criteria or disinvestment) assuming that a life-cycle reassessment platform existed.”

4.4. Increasing Transparency on Performance Measures

4.5. Value of Criterion 7 (Availability of Expertise and Methodology)

5. MCDA Process (Consensus Building and Deliberation): Observations, Feedback, and Lessons Learned

| Criteria | Rating Scale | Weight | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Group A—Criteria to Assess the Importance of the RWE Question | |||||

| Criterion 1: Drug’s perceived clinical benefit (quantitative assessment) The objective of this criterion is to evaluate the perceived clinical benefit of the therapy compared to existing options. The “perceived” clinical benefit is based on the currently available objective evidence, with preference given to primary clinical trial data or indirect comparisons, a utilized in the setting of single-arm studies or to assess effectiveness in comparison to contemporary Canadian standard-of-care treatments. Assessment of the perceived clinical benefit is based on ratings derived from the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (MCBS) version 1.1 [17]. Users are asked to provide a quantitative assessment using the ESMO-MCBS-endorsed rating. The ESMO-MCBS-endorsed rating will be provided in the corresponding vignette (if available); if not, CanREValue will provide a suggested score based on the ESMO-MCBS evaluation forms. Recognizing inter-rater variability, users are asked to double check the suggested score using the information provided in the vignette and corresponding evaluations found below. ESMO-MCBS (v1.1) scores:

| Rated using the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (MCBS) v1.0. [17] | 17.65 | |||

| Minimal to low clinically meaningful incremental benefit, as evidenced by ESMO-MCBS v1.1 score of: (a) Curative setting: Grade C for new approaches to adjuvant therapy or potentially new curative therapies (please refer to Evaluation Form 1 below for details on rating); or (b) Non-curative setting: Grade 1 or 2 for therapies that are not likely to be curative (please refer to relevant Evaluation Form 2a, 2b, 2/c, or 3 below, depending on primary endpoint available for details on rating). | Moderate clinically meaningful incremental benefit, as evidenced by ESMO-MCBS v1.1 score of: (a) Curative setting: Grade B for new approaches to adjuvant therapy or potentially new curative therapies (please refer to Evaluation Form 1 below for details on rating); or (b) Non-curative setting: Grade 3 for therapies that are not likely to be curative (please refer to relevant Evaluation Form 2a, 2b, 2c, or 3 below, depending on primary endpoint available for details on rating). | Substantial clinically meaningful incremental benefit, as evidenced by ESMO-MCBS v1.1 score of: (a) Curative setting: Grade A for new approaches to adjuvant therapy or potentially new curative therapies (please refer to Evaluation Form 1 below for details on rating); or (b) Non-curative setting: Grade 4 or 5 for therapies that are not likely to b e curative (please refer to relevant Evaluation Form 2a, 2b, 2c, or 3 below, depending on primary endpoint available for details on rating). | |||

| Criterion 2: Magnitude of perceived uncertainty (qualitative assessment) The objective of this criterion is to assess the degree of uncertainty regarding the endpoint in question. Users are asked to provide a qualitative assessment of whether the primary clinical trial data available is characterized by features of minimal, moderate, or substantial uncertainty. There may be features related to the design of the study that may make the results of the study or the expected clinical benefit of the drug to be more uncertain. Common attributes to consider when ascertaining uncertainty include, but are not limited to: | Minimal uncertainty | Moderate uncertainty | Substantial uncertainty | 10.6 | |

| ☐ Immature trial data; ☐ Single arm studies; ☐ Use of surrogate endpoints; | Phase of the trial: Consider whether the trial was early or late phase ☐ Phase I ☐ Phase II ☐ Phase III | ||||

| ☐ Trials lacking a relevant Canadian standard-of-care comparator; ☐ Existing controversary in the literature or clinical practice; | ☐ RWE Applicability: Consider whether there are concerns with generalizability of the trial to the general unselected population in the real world ☐ Other uncertainties Consider other possible sources of uncertainty | ||||

| Criterion 3: Relevance of uncertainty (qualitative assessment) The objective of this criterion is to assess the relevance of resolving the uncertainty to decision-makers. Specifically, users are asked to provide a qualitative assessment on whether the data generated from the proposed RWE study could lead to future policy change (i.e., price re-negotiation, change in funding criteria, or disinvestment), assuming that a health technology life-cycle reassessment platform existed. | Low relevance: As assessed by expert opinions, there is an expected low likelihood for the findings of the proposed RWE study to facilitate a change in policy (i.e., price re-negotiation, change in funding criteria, disinvestment). | Moderate relevance: As assessed by expert opinions, there is uncertainty in the likelihood for the findings of the proposed RWE study to facilitate a change in policy (i.e., price re-negotiation, change in funding criteria, disinvestment). | Substantial relevance: As assessed by expert opinions, there is an expected high likelihood for the findings of the proposed RWE study to facilitate a change in policy (i.e., price re-negotiation, change in funding criteria, disinvestment). | 18.8 | |

| Group B—Criteria to Assess the Feasibility of the RWE Project | |||||

| Criterion 4: Identification and assembly of cases and comparator control cohort (qualitative assessment) The objective of this criterion is to assess the likelihood that cases and a relevant historical Canadian comparator cohort can be identified and assembled in at least one Canadian province. A ”relevant” comparator is a group of patients that has been treated according to current Canadian standard of care regimen. To rate this criterion, users are asked to provide a qualitative assessment by assessing whether cases and the comparator cohort can be identified based on the availability and completeness of data pertaining to (a) type of cancer (i.e., primary cancer), (b) type of treatment received, and (c) clinical characteristics (i.e., biomarkers, stage, etc.). Note: Sample size of the cases and comparator control cohort should not be considered for the rating of this criterion, as it will be considered in the rating of Criterion 5 (Sample size for cases and comparator control cohort). Further, the availability of covariates and outcomes should not be considered for the rating of this criterion, as it will be considered in the rating of Criterion 6 (Availability of Data for Covariates and Outcomes). | Substantial concern | Moderate concern | Low concern | 11.8 | |

| Criterion 5: Sample sizes for cases and comparator control cohort (qualitative assessment) The objective of this criterion is to assess the likelihood that there will be a sufficient sample size of patients receiving the treatment in question (cases) and that a relevant historical Canadian comparator cohort (control) can be identified within a reasonable time frame (i.e., within time to be relevant to the funding decision). Users are asked to provide a qualitative assessment by referring to the formal sample size calculation provided in the respective vignette to perform rating for this criterion. | Substantial concern: Unlikely to establish a sufficient sample size within a reasonable timeframe to effect meaningful policy change. | Moderate concern: Likely to establish a sufficient sample size (as noted in rating scale 3) but additional concern noted (e.g., concern for loss of sample size for cases due to emerging alternative novel therapies with upcoming availability through access programs or public funding). | Low concern: Very likely to establish a sufficient sample size within a reasonable timeframe to effect meaningful policy change. | 14.1 | |

| Criterion 6: Availability of data for covariates and outcomes (qualitative assessment) The objective of this criterion is to assess the availability and completeness of data in at least one Canadian province for key covariates and outcome of interest. To rate this criterion, users are asked to provide a qualitative assessment by assessing whether key criteria and outcomes can be identified within currently available administrative databases pertaining to data for: (a) Covariates: Relevant patient and/or disease characteristics required to be adjusted and/or accounted for given the non-randomized nature of RWE study design (e.g., consider baseline characteristics listed in Table 1 of the pivotal clinical trial). (b) Outcome of interest Please note: If the uncertainty is related to cost, users are also to consider data for relevant costing inclusive of total healthcare costs accrued during treatment (e.g., systemic treatment, planned and unplanned healthcare resource utilization). Note: Sample size of the exposed cohort should not be considered for the rating of this criterion (as sample size is considered in the rating of Criterion 5 “Sample size for cases and comparator control cohort”). | Substantial concern | Moderate concern | Low concern | 17.65 | |

| Criterion 7: Availability of Expertise and Methodology (qualitative assessment) The objective of this criterion is to evaluate the availability of required expertise (e.g., clinical experts, data analysts, and methodologists) and methodology to conduct the study. Users are asked to provide a qualitative assessment. | Substantial concern: Expected challenges to find the necessary expertise and need to develop new methods to conduct the study, with above limitations in data taken into consideration (if applicable). | Moderate concern: Expected challenges to find the necessary expertise or need to develop new methods to conduct the study, with above limitations in data taken into consideration (if applicable). | Low concern: No expected issues with the availability of the necessary expertise and no new methods required to conduct the study. | 9.4 | |

6. Summary and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Initial Set of MCDA Criteria

| Criteria | Rating Scale | Weight | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Group A—Criteria to Assess the Importance of the RWE Question | ||||

| Drug’s perceived incremental benefit: The objective of this criterion is to evaluate the perceived clinical benefit of the therapy compared to existing options. The ‘perceived’ clinical benefit is based on the currently available objective evidence (including primary clinical trial data and indirect comparisons 1) and expected long-term outcomes (in the setting of immature data). | Rated using the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (MCBS) v1.0. [17] | 17.65 | ||

| Minimal to low clinically meaningful incremental benefit, as evidenced by: (a) overall survival benefit demonstrated through a hazard ratio >0.65 and/or gain in median overall survival of <2.5 months, as compared to current standard(s) of care, for therapies with a median overall survival of <1 year; or (b) overall survival benefit demonstrated through a hazard ratio of >0.70 and/or gain in median overall survival of <3 months, as compared to current standard(s) of care, for therapies with a median overall survival > 1 year; or (c) median progression free survival benefit demonstrated through a hazard ratio of >0.65, as compared to current standard(s) of care; or) clinical benefit demonstrated in an alternative outcome (including improvements in response rate, quality-of-life or other clinically meaningful outcome). | Moderate clinically meaningful incremental benefit, as evidenced by: (a) survival benefit demonstrated by a hazard ratio ≤0.65 and gain in median survival of 2.5–2.9 months, as compared to current standard(s) of care, for therapies with median overall survival ≤ 1 year; or (b) overall survival benefit demonstrated by a hazard ratio ≤0.70 and gain in median overall survival of 3–4.9 months, as compared to current standard(s) of care, for therapies with median overall survival > 1 year; or (c) progression-free survival benefit demonstrated by a hazard ratio ≤0.65 and gain ≥1.5 months, as compared to current standard(s) of care. | Substantial clinically meaningful incremental benefit, as evidenced by: (a) overall survival benefit demonstrated through a hazard ratio of <0.65 and gain in median overall survival of 2.5–3.0 months, as compared to current standard(s) of care, for therapies with median overall survival < 1 year; or (b) overall survival benefit demonstrated through a hazard ratio ≤ 0.70 and gain in median overall survival of ≥5 months, as compared to current standard(s) of care, for therapies with median overall survival > 1 year. | ||

| Magnitude of uncertainty: The objective of this criterion is to assess the degree of uncertainty in question (the uncertainty can be about toxicity, clinical effectiveness, quality-of-life, treatment sequence, generalizability of benefits, costs or other). | Minimal uncertainty: This can be based upon either a qualitative assessment or quantitative assessment (the latter can be conceptualized as a <10% variation in either of the following: (a) the confidence intervals around the survival estimates; (b) the upper and lower range of ICERs from the pCODR assessment 1). | Moderate uncertainty: This can be based upon either a qualitative assessment or quantitative assessment (the latter can be conceptualized as a 10–25% variation in either of the following: (a) the confidence intervals around the survival estimates; (b) the upper and lower range of ICERs from the pCODR assessment 1). | Substantial uncertainty: This can be based upon either a qualitative assessment or quantitative assessment (the latter can be conceptualized as a >25% variation in either of the following: (a) the confidence intervals around the survival estimates; (b) the upper and lower range of ICERs from the pCODR assessment 1). | 10.6 |

| Relevance of uncertainty: The objective of this criterion is to assess the relevance of resolving the uncertainty to decision-makers (i.e., what is the likelihood that resolving the uncertainty with new evidence will alter the funding status or clinical treatment recommendations). | Indirect relevance: As assessed by expert opinions, there is an expected low likelihood for new evidence to facilitate a change in funding status (i.e., facilitate drug price re-negotiations) and/or change in clinical treatment recommendations (i.e., indicated patient populations or treatment sequence). | Moderate relevance: As assessed by expert opinions, there is uncertainty in the likelihood for new evidence to facilitate a change in funding status (i.e., facilitate drug price re-negotiations) and/or change in clinical treatment recommendations (i.e., indicated patient populations or treatment sequence). | Substantial relevance: As assessed by expert opinions, there is an expected high likelihood for new evidence to facilitate a change in funding status (i.e., facilitate drug price re-negotiations) and/or change in clinical treatment recommendations (i.e., indicated patient populations or treatment sequence). | 18.8 |

| Group B—Criteria to Assess the Feasibility of the RWE Project | ||||

| Comparator: The objective of this criterion is to assess the likelihood that a relevant historical or contemporaneous Canadian comparator population, of sufficient size, can be identified within a reasonable time frame (i.e., within time to be relevant to the funding decision, for contemporaneous control). A ‘relevant’ comparator is a group that has been treated according to current Canadian standard of care regimen. | Substantial concern: Unlikely to identify an appropriate comparator population within a reasonable time due to absence of clear standard-of-care therapy (i.e., >2 relevant standard-of-care treatments currently available or evolving standard-of-care treatment) and/or low-volume patient population. | Moderate concern: Moderate concern for the identification of an appropriate comparator population due to absence of clear standard-of-care therapy (i.e., 2 relevant standard-of-care treatments currently available) and/or moderate-volume patient population. | Low concern: Appropriate comparator population will be easily identified due to a well-defined standard of care therapy and high-volume patient population. | 11.8 |

| Cases: The objective of this criterion is to assess the likelihood that there will be enough patients receiving the treatment in question to have a sufficient sample size within a reasonable time frame (i.e., within time to be relevant to the funding decision). | Substantial concern: Unlikely to establish a sufficient sample size (with appropriate follow-up for relevant outcome(s)) within a reasonable time 2 based upon expected incidence of disease (using Canadian provincial estimates) and required sample size for analysis. | Moderate concern: Likely to establish a sufficient sample size, based upon expected incidence of disease (using Canadian provincial estimates) but unlikely to have follow-up for relevant outcome(s) within a reasonable time 2 based upon expected incidence (using Canadian provincial estimates) and required sample size for analysis. | Low concern: Very likely to establish a sufficient sample size (with appropriate follow-up for relevant outcome(s)) within a reasonable time 2 based upon expected incidence of disease (using Canadian provincial estimates) and required sample size for analysis. | 14.1 |

| Data: The objective of this criterion is to assess the quality of data available in at least one Canadian province to address the uncertainty. This requires an assessment of the availability and completeness of data for both the exposed and comparator cohorts pertaining to: (a) data for relevant patient and disease characteristics to account for important co-variates, ensure un-biased comparability between groups and measure relevant outcomes +/− (b) data for relevant costing inclusive of total health care costs accrued during treatment (ex. systemic treatment, planned and unplanned health care resource utilization). | Substantial concern: Substantial concern for the availability of high-quality and complete data for both exposed and comparator cohorts in known real-world databases (as assessed by an absence of ≥1 of the following: (a) patient and/or disease characteristics required to define current funding eligibility; (b) >2 relevant patient and/or disease co-variates; (c) ability to identify primary systemic treatment, inclusive of line-of-therapy). | Moderate concern: Moderate concern for the availability of high-quality and complete data for both exposed and comparator cohorts in known real-world databases (as assessed by an absence of ≥1 of the following: (a) 1–2 relevant patient and/or disease co-variates; (b) ability to identify prior or subsequent treatment inclusive of line-of-therapy). | Low concern: No expected issues in accessing high-quality and complete data in known real-world databases. | 17.65 |

| Expertise and Methodology: The objective of this criterion is to evaluate the availability of required expertise (ex. clinical experts, data analysts and methodologists) and methodology to conduct the study. | Substantial concern: Expected challenges to find the necessary expertise and need to develop new methods to conduct the study, with above limitations in data taken into consideration (if applicable). | Moderate concern: Expected challenges to find the necessary expertise or need to develop new methods to conduct the study, with above limitation in data taken into consideration (if applicable). | Low concern: No expected issues with the availability of the necessary expertise and no new methods required to conduct the study. | 9.4 |

References

- Impact of RWE on HTA Decision-Making. IQVIA Institute December 2022. Available online: https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports-and-publications/reports/impact-of-rwe-on-hta-decision-making (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- CADTH. Guidance for Reporting Real-World Evidence; CADTH: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023; Available online: https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/RWE/MG0020/MG0020-RWE-Guidance-Report-Secured.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Real-World Evidence Framework. 2022. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/corporate/ecd9/resources/nice-realworld-evidence-framework-pdf-1124020816837 (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Framework for FDA’s Real-World Evidence Program; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/120060/download?attachment (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Health Canada. Elements of Real World Data/Evidence Quality throughout the Prescription Drug Product Life Cycle; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/health/publications/drugs-health-products/real-world-data-evidence-drug-lifecycle-report.html (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- CoLab: Canada’s Leader in Post-Market Drug Evaluation. CADTH. Available online: https://colab.cadth.ca/#meet-the-colab-network (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Garrison, L.P., Jr.; Neumann, P.J.; Erickson, P.; Marshall, D.; Mullins, C.D. Using real-world data for coverage and payment decisions: The ISPOR Real-World Data Task Force report. Value Health J. Int. Soc. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2007, 10, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.; Nam, S.; Evans, B.; de Oliveira, C.; Chambers, A.; Gavura, S.; Hoch, J.; Mercer, R.E.; Dai, W.F.; Beca, J.; et al. Developing a framework to incorporate real-world evidence in cancer drug funding decisions: The Canadian Real-world Evidence for Value of Cancer Drugs (CanREValue) collaboration. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e032884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, W.F.; Arciero, V.; Craig, E.; Fraser, B.; Arias, J.; Boehm, D.; Bosnic, N.; Caetano, P.; Chambers, C.; Jones, B.; et al. Considerations for Developing a Reassessment Process: Report from the Canadian Real-World Evidence for Value of Cancer Drugs (CanREValue) Collaboration’s Reassessment and Uptake Working Group. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 4174–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gongora-Salazar, P.; Rocks, S.; Fahr, P.; Rivero-Arias, O.; Tsiachristas, A. The Use of Multicriteria Decision Analysis to Support Decision Making in Healthcare: An Updated Systematic Literature Review. Value Health J. Int. Soc. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2023, 26, 780–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thokala, P.; Devlin, N.; Marsh, K.; Baltussen, R.; Boysen, M.; Kalo, Z.; Longrenn, T.; Mussen, F.; Peacock, S.; Watkins, J.; et al. Multiple criteria decision analysis for health care decision making—An introduction: Report 1 of the ISPOR MCDA Emerging Good Practices Task Force. Value Health 2016, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, K.; Ijzerman, M.; Thokala, P.; Baltussen, R.; Boysen, M.; Kaló, Z.; Lönngren, T.; Mussen, F.; Peacock, S.; Watkins, J.; et al. Multiple criteria decision analysis for health care decision making—Emerging good practices: Report 2 of the ISPOR MCDA Emerging Good Practices Task Force. Value Health 2016, 19, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, A.; Dai, W.F.; Dionne, F.; Geirnaert, M.; Denburg, A.; Ahuja, T.; Beca, J.; Bouchard, S.; Chambers, C.; Hunt, M.J.; et al. Development of a Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Rating Tool to Prioritize Real-World Evidence Questions for the Canadian Real-World Evidence for Value of Cancer Drugs (CanREValue) Collaboration. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 3776–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, K.D.; Sculpher, M.; Caro, J.J.; Tervonen, T. The Use of MCDA in HTA: Great Potential, but More Effort Needed. Value Health J. Int. Soc. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2018, 21, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltussen, R.; Marsh, K.; Thokala, P.; Diaby, V.; Castro, H.; Cleemput, I.; Garau, M.; Iskrov, G.; Olyaeemanesh, A.; Mirelman, A.; et al. Multicriteria Decision Analysis to Support Health Technology Assessment Agencies: Benefits, Limitations, and the Way Forward. Value Heal. J. Int. Soc. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2019, 22, 1283–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oortwijn, W.; Husereau, D.; Abelson, J.; Barasa, E.; Bayani, D.D.; Santos, V.C.; Culyer, A.; Facey, K.; Grainger, D.; Kieslich, K.; et al. Designing and Implementing Deliberative Processes for Health Technology Assessment: A Good Practices Report of a Joint HTAi/ISPOR Task Force. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2022, 38, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherny, N.I.; Sullivan, R.; Dafni, U.; Kerst, J.M.; Sobrero, A.; Zielinski, C.; de Vries, E.G.E.; Piccart, M.J. A Standardized, generic, validated approach to stratify the magnitude of clinical benefit that can be anticipated from anti-cancer therapies: The European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS). Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1547–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dionne, F.; Mitton, C.; Macdonald, T.; Miller, C.; Brennan, M. The challenge of obtaining information necessary for multi-criteria decision analysis implementation: The case of physiotherapy services in Canada. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2013, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelis, A.; Linch, M.; Montibeller, G.; Molina-Lopez, T.; Zawada, A.; Orzel, K.; Arickx, F.; Espin, J.; Kanavos, P. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis for HTA across four EU Member States: Piloting the Advance Value Framework. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 246, 112595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, H.E.; Moreno-Mattar, O.; Rivillas, J.C. HTA and MCDA solely or combined? The case of priority-setting in Colombia. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2018, 16 (Suppl. 1), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jedai, A.; Almudaiheem, H.; Alruthia, Y.; Althemery, A.; Alabdulkarim, H.; Ojeil, R.; Alrumaih, A.; AlGhannam, S.; AlMutairi, A.; Hasnan, Z. A Step Toward the Development of the First National Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Framework to Support Healthcare Decision Making in Saudi Arabia. Value Health Reg. Issues 2024, 41, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M.D.; Mataloto, I.; Kanavos, P. Multi-criteria decision analysis for health technology assessment: Addressing methodological challenges to improve the state of the art. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2019, 20, 891–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, F.; Bowen, J.M.; Sutherland, S.C.; Burke, N.; Blackhouse, G.; Tarride, J.E.; O’Reilly, D.; Goeree, R. Using health technology assessment to support evidence-based decision-making in Canada: An academic perspective. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2011, 11, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laba, T.-L.; Jiwani, B.; Crossland, R.; Mitton, C. Can multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) be implemented into realworld drug decision-making processes? A Canadian provincial experience. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2020, 36, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeife, D.A.; Dionne, F.; Fares, A.F.; Cusano, E.L.R.; Fazelzad, R.; Ng, W.; Husereau, D.; Ali, F.; Sit, C.; Stein, B.; et al. Value assessment of oncology drugs using a weighted criterion-based approach. Cancer 2020, 126, 1530–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Validation Exercise Meeting Dates | RWE Proposal | Research Question(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 18 August 2021 | Polatuzumab vedotin for relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | What is the real-world comparative effectiveness (overall survival) of polatuzumab vedotin in combination with bendamustine and rituximab in patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) who are not eligible for autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) and have received at least one prior therapy, as compared to standard systemic therapy? |

| 22 November 2021 | Dabrafenib and Trametinib for BRAF V600E mutation Positive Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | What is the real-world progression-free survival (RQ1) of dabrafenib and trametinib as first line-line systemic therapy in patients with BRAF V600E mutation positive metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), as compared to standard platinum-doublet chemotherapy +/− pembrolizumab? |

| What is the real-world overall survival (RQ2) of dabrafenib and trametinib as first line-line systemic therapy in patients with BRAF V600E mutation positive metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), as compared to standard platinum-doublet chemotherapy +/− pembrolizumab? | ||

| What is the real-world time to next treatment (RQ3) of dabrafenib and trametinib as first line-line systemic therapy in patients with BRAF V600E mutation positive metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), as compared to standard platinum-doublet chemotherapy +/− pembrolizumab? | ||

| What is the real-world duration of treatment (RQ4) of dabrafenib and trametinib as first line-line systemic therapy in patients with BRAF V600E mutation positive metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), as compared to standard platinum-doublet chemotherapy +/− pembrolizumab? | ||

| 23 February 2022 | Nivolumab in relapsed/ Refractory Classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma | What is the real-world overall survival of nivolumab in patients with classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma with evidence of disease progression following autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) and brentuximab vedotin (BV), as compared to standard single-agent chemotherapy or pembrolizumab immunotherapy? * |

| Atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab for unresectable/metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma | What is the real-world overall survival of atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with unresectable or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), as compared to either sorafenib or lenvatinib? | |

| 23 June 2022 | Durvalumab in Combination with Platinum Etoposide for Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer | What is the real-world overall survival of durvalumab in combination with platinum-etoposide as first-line treatment for patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer, as compared to platinum-etoposide alone? |

| Nivolumab in Combination with Fluoropyrimidine and Platinum-containing Chemotherapy for Metastatic Gastric Adenocarcinoma | What is the real-world overall survival of nivolumab in combination with fluoropyrimidine and platinum-containing chemotherapy as first-line systemic therapy for HER-2 negative locally advanced or metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma, as compared to fluoropyrimidine and platinum-containing chemotherapy alone? | |

| 5 December 2022 | Nivolumab in Combination with Fluoropyrimidine and Platinum-containing Chemotherapy for Metastatic Gastric Adenocarcinoma † | What is the real-world overall survival of nivolumab in combination with fluoropyrimidine and platinum-containing chemotherapy as first-line systemic therapy for HER-2 negative locally advanced or metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma, as compared to fluoropyrimidine and platinum-containing chemotherapy alone? |

| Meeting Dates | RWE Proposal | Endpoint | Consensus Score * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Importance | Feasibility | Total | Priority | |||

| 18 August 2021 | Polatuzumab vedotin for relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | OS | 122 | 104 | 226 | High |

| 22 November 2021 | Dabrafenib and trametinib for BRAF V600E mutation Positive Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | PFS | 87 | 98 | 185 | Low |

| OS | 124 | 133 | 256 | High | ||

| TTNT | 68 | 129 | 198 | Low | ||

| DOT | n/a † | n/a † | n/a † | n/a † | ||

| 23 February 2022 | Nivolumab in relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma | OS | 105 | 115 | 220 | Medium |

| Atezolizumab in combination with Bevacizumab for unresectable/metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma | OS | 105 | 107 | 212 | Medium | |

| 23 June 2022 | Durvalumab in Combination with Platinum Etoposide for Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer | OS | 68 | 141 | 209 | Medium |

| Nivolumab in Combination with Fluoropyrimidine and Platinum-containing Chemotherapy for Metastatic Gastric Adenocarcinoma | OS | 58 | 127 | 185 | Low | |

| 5 December 2022 | Nivolumab in Combination with Fluoropyrimidine and Platinum-containing Chemotherapy for Metastatic Gastric Adenocarcinoma ‡ | OS | 77 | 127 | 204 | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Takhar, P.; Geirnaert, M.; Gavura, S.; Beca, J.; Mercer, R.E.; Denburg, A.; Muñoz, C.; Tadrous, M.; Parmar, A.; Dionne, F.; et al. Application of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) to Prioritize Real-World Evidence Studies for Health Technology Management: Outcomes and Lessons Learned by the Canadian Real-World Evidence for Value of Cancer Drugs (CanREValue) Collaboration. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 1876-1898. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31040141

Takhar P, Geirnaert M, Gavura S, Beca J, Mercer RE, Denburg A, Muñoz C, Tadrous M, Parmar A, Dionne F, et al. Application of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) to Prioritize Real-World Evidence Studies for Health Technology Management: Outcomes and Lessons Learned by the Canadian Real-World Evidence for Value of Cancer Drugs (CanREValue) Collaboration. Current Oncology. 2024; 31(4):1876-1898. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31040141

Chicago/Turabian StyleTakhar, Pam, Marc Geirnaert, Scott Gavura, Jaclyn Beca, Rebecca E. Mercer, Avram Denburg, Caroline Muñoz, Mina Tadrous, Ambica Parmar, Francois Dionne, and et al. 2024. "Application of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) to Prioritize Real-World Evidence Studies for Health Technology Management: Outcomes and Lessons Learned by the Canadian Real-World Evidence for Value of Cancer Drugs (CanREValue) Collaboration" Current Oncology 31, no. 4: 1876-1898. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31040141

APA StyleTakhar, P., Geirnaert, M., Gavura, S., Beca, J., Mercer, R. E., Denburg, A., Muñoz, C., Tadrous, M., Parmar, A., Dionne, F., Boehm, D., Chambers, C., Craig, E., Trudeau, M., Cheung, M. C., Houlihan, J., McDonald, V., Pechlivanoglou, P., Taylor, M., ... Chan, K. K. W. (2024). Application of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) to Prioritize Real-World Evidence Studies for Health Technology Management: Outcomes and Lessons Learned by the Canadian Real-World Evidence for Value of Cancer Drugs (CanREValue) Collaboration. Current Oncology, 31(4), 1876-1898. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31040141