Symptom Reporting Behaviors, Symptom Burden, and Quality of Life in Patients with Hormone Receptor–Positive Breast Cancer Undergoing Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Statistical Analysis

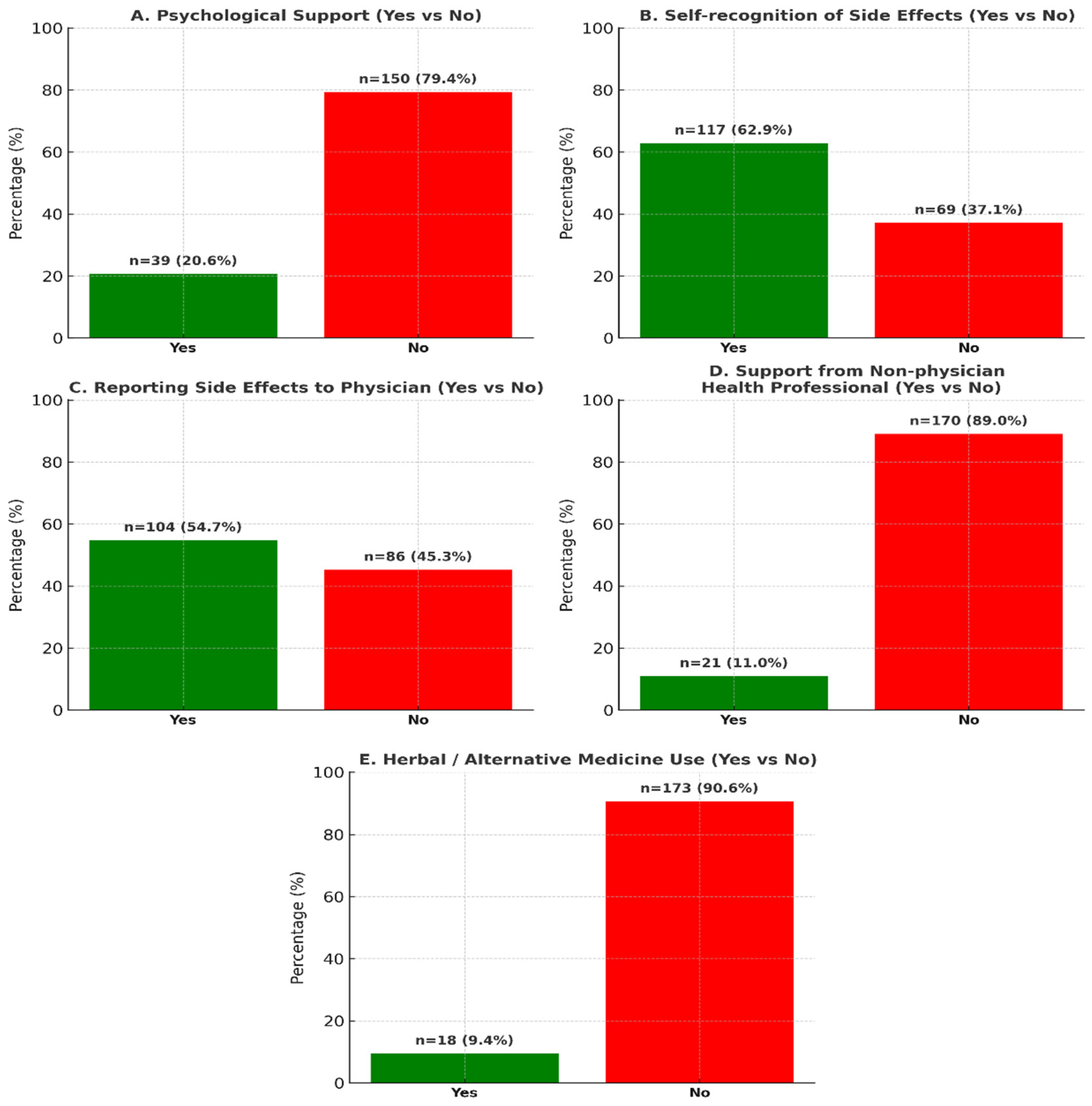

2.3. Findings

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen in early breast cancer: Patient-level meta-analysis of the randomized trials. Lancet 2015, 386, 1341–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer. Version 4.2023. Available online: https://www.nccn.org (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Davies, C.; Pan, H.; Godwin, J.; Gray, R.; Arriagada, R.; Raina, V.; Abraham, M.; Medeiros Alencar, V.H.; Badran, A.; Bonfill, X.; et al. Adjuvant Tamoxifen: Longer Against Shorter (ATLAS) Collaborative Group. Long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years after diagnosis of estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer: ATLAS, a randomized trial. Lancet 2013, 381, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, P.A.; Pagani, O.; Fleming, G.F.; Walley, B.A.; Colleoni, M.; Láng, I.; Gómez, H.L.; Tondini, C.; Ciruelos, E.; Burstein, H.J.; et al. SOFT and TEXT Investigators and International Breast Cancer Study Group. Tailoring adjuvant endocrine therapy for premenopausal breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Reeve, B.B.; Mitchell, S.A.; Clauser, S.B.; Minasian, L.M.; Dueck, A.C.; Mendoza, T.R.; Hay, J.; Atkinson, T.M.; Abernethy, A.P.; et al. Development of the National Cancer Institute’s patient-reported outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueck, A.C.; Mendoza, T.R.; Mitchell, S.A.; Reeve, B.B.; Castro, K.M.; Rogak, L.J.; Atkinson, T.M.; Bennett, A.V.; Denicoff, A.M.; O’Mara, A.M.; et al. Validity and reliability of the US National Cancer Institute’s patient-reported outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademaker, L.M.; Gal, R.; May, A.M.; Batenburg, M.C.T.; van der Leij, F.; Bijlsma, R.M.; Verkooijen, H.M.; Doeksen, A.; Ernst, M.F.; Evers, D.J.; et al. Side-effects in women treated with adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Breast 2025, 80, 104416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrar, M.; Peddie, N.; Agnew, S.; Diserholt, A.; Fleming, L. Breast Cancer Survivors’ Lived Experience of Adjuvant Hormone Therapy: A Thematic Analysis of Medication Side Effects and Their Impact on Adherence. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 861198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; de Haes, J.C.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprangers, M.A.; Groenvold, M.; Arraras, J.I.; Franklin, J.; te Velde, A.; Muller, M.; Franzini, L.; Williams, A.; de Haes, H.C.; Hopwood, P.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer–specific quality-of-life module (QLQ-BR23): First results from a three-country field study. J. Clin. Oncol. 1996, 14, 2756–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assad-Suzuki, D.; Laperche-Santos, D.; Resende, H.; Moura, F.C.; Oliveira, S.C.S.; Shimada, A.K.; Arakelian, R.; Galvão, A.L.Z.; de Souza, B.S.W.; Custódio, A.G.C.; et al. Adherence to Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Patients With Nonmetastatic Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: A Comprehensive Brazilian Real-World Data Study. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2025, 11, e2400351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menz, B.D.; Modi, N.D.; Abuhelwa, A.Y.; Kuderer, N.M.; Lyman, G.H.; Swain, S.M.; Kichenadasse, G.; Shahnam, A.; Haseloff, M.; Vitry, A.; et al. Patient-reported outcome thresholds and their associations with survival, adverse events, and quality of life in a pooled analysis of breast cancer trials. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 157, 2135–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhard, J.; Luo, W.; Ribi, K.; Colleoni, M.; Burstein, H.J.; Tondini, C.; Pinotti, G.; Spazzapan, S.; Ruhstaller, T.; Puglisi, F.; et al. Patient-reported outcomes with adjuvant exemestane plus ovarian function suppression versus tamoxifen plus ovarian function suppression in premenopausal women with early breast cancer: A combined analysis of the TEXT and SOFT trials. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribi, K.; Luo, W.; Bernhard, J.; Francis, P.A.; Burstein, H.J.; Ciruelos, E.; Bellet, M.; Pavesi, L.; Lluch, A.; Visini, M.; et al. Adjuvant tamoxifen with or without ovarian function suppression in premenopausal women with early breast cancer: Patient-reported outcomes in the TEXT and SOFT trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1601–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallowfield, L.; Cella, D.; Cuzick, J.; Francis, S.; Locker, G.; Howell, A. Quality of life of postmenopausal women in the Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination adjuvant breast cancer trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 4261–4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basch, E.; Iasonos, A.; McDonough, T.; Barz, A.; Culkin, A.; Kris, M.G.; Scher, H.I.; Schrag, D. Patient versus clinician symptom reporting using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: Results of a questionnaire-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2006, 7, 903–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maio, M.; Gallo, C.; Leighl, N.B.; Piccirillo, M.C.; Daniele, G.; Nuzzo, F.; Gridelli, C.; Gebbia, V.; Ciardiello, F.; De Placido, S.; et al. Symptomatic toxicities experienced during anticancer treatment: Agreement between patient and physician reporting in three randomized trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Patient-Reported Outcomes Version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). Available online: https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/pro-ctcae/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Faller, H.; Schuler, M.; Richard, M.; Heckl, U.; Weis, J.; Küffner, R. Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, W.K.W.; Law, B.M.H.; Ng, M.S.N.; He, X.; Chan, D.N.S.; Chan, C.W.H.; McCarthy, A.L. Symptom clusters experienced by breast cancer patients at various treatment stages: A systematic review. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 2531–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwekkeboom, K.L.; Wieben, A.; Braithwaite, L.; Hopfensperger, K.; Kim, K.S.; Montgomery, K.; Reske, M.; Stevens, J. Characteristics of Cancer Symptom Clusters Reported through a Patient-Centered Symptom Cluster Assessment. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 44, 662–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Ren, S.; Jin, J.; Xu, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, W.; Lu, T.; Lin, H.; Liu, J. Symptom burden and symptom clusters in patients with breast cancer undergoing endocrine therapy: A cross-sectional survey. Support. Care Cancer 2025, 33, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitlinger, A.; Shelby, R.A.; Van Denburg, A.N.; White, H.; Edmond, S.N.; Marcom, P.K.; Bosworth, H.B.; Keefe, F.J.; Kimmick, G.G. Higher symptom burden is associated with lower function in women taking adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2019, 10, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan Nayeri, N.; Bakhshi, F.; Khosravi, A.; Najafi, Z. The effect of complementary and alternative medicine on the quality of life of patients with breast cancer: A systematic review. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2020, 26, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.; Zhao, F.; Yu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Li, C.G. Interactions Between Natural Products and Tamoxifen in Breast Cancer: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 847113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncology Nursing Society. Complementary and Integrative Therapies in Supportive Care: Levels of Evidence and Recommendations. Available online: https://www.ons.org (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Basch, E.; Deal, A.M.; Dueck, A.C.; Scher, H.I.; Kris, M.G.; Hudis, C.; Schrag, D. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA 2017, 318, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Walker, M.S.; Stepanski, E.; Kaplan, C.M.; Martin, M.Y.; Vidal, G.A.; Schwartzberg, L.S.; Graetz, I. Racial Differences in Patient-Reported Symptoms and Adherence to Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy Among Women With Early-Stage, Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2225485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, V.B.; Sutton, A.L.; Hurtado-de-Mendoza, A.; He, J.; Dahman, B.; Edmonds, M.C.; Hackney, M.H.; Tadesse, M.G. Race and Patient reported Symptoms in Adherence to Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy: A Report from the Women’s Hormonal Initiation and Persistence Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2021, 30, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, M.J.; Inoue, K.; Matsuda, A.; Kroep, J.R.; Nagai, S.; Tozuka, K.; Momiyama, M.; Weijl, N.I.; Langemeijer-Bosman, D.; Ramai, S.R.S.; et al. Cross-cultural comparison of breast cancer patients’ Quality of Life in the Netherlands and Japan. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 166, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Quality of Life Group. Update on the Breast Cancer–Specific Module (EORTC QLQ-BR45). Available online: https://www.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/08/Specimen-BR45-English.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

| n = 191 | |

|---|---|

| Age (Med.) | 54 (46–61) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 191 (100%) |

| Menopausal Status | |

| Pre-Perimenopause | 73 (38.2%) |

| Postmenopausal | 118 (61.8%) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0–1 | 191 (100%) |

| Comorbid Disease | |

| None | 60 (31.4%) |

| Yes | 131 (68.6%) |

| Diagnosis Stage | |

| 1 | 74 (38.7%) |

| 2 | 72 (37.7%) |

| 3 | 45 (23.6%) |

| C-Erb B2 | |

| Negative | 146 (76.4%) |

| Positive | 45 (23.6%) |

| Chemotherapy History | |

| None | 33 (17.3%) |

| Yes | 156 (81.7%) |

| Unknown | 2 (1.0%) |

| History of Radiotherapy | |

| None | 26 (13.6%) |

| Yes | 165 (86.4%) |

| Type of Hormone Therapy | |

| Tamoxifen | 71 (37.2%) |

| Aromatase Inhibitor | 120 (62.8%) |

| Using OFS | |

| None | 135 (70.7%) |

| Yes | 56 (29.3%) |

| Educational Status | |

| Elementary-Middle School | 95 (49.7%) |

| High School-Undergraduate-Graduate | 90 (47.1%) |

| Unknown | 6 (3.1%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 131 (68.6%) |

| Single/Widowed | 56 (29.3%) |

| Unknown | 4 (2.1%) |

| Employment Status | |

| Employed | 43 (22.5%) |

| Not actively working | 148 (77.5%) |

| Univariate Analyses | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Symptom Burden Score (Low/High) | p Value | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | p Value | |

| Age | 0.001 | 0.240 | ||

| ≤50 (Ref.) | 31.4%/68.6% | |||

| >50 | 56.2%/43.8% | 0.54 (0.19–1.51) | ||

| Menopausal Status | 0.005 | 0.759 | ||

| Postmenopausal (Ref.) | 55.1%/44.9% | |||

| Pre-Perimenopause | 34.2%/65.8 | 1.27 (0.28–5.77) | ||

| Stage | 0.189 | |||

| 1 (Ref.) | 55.4%/44.6 | |||

| 2 | 41.7%/58.3% | 1.24 (0.53–2.92) | 0.619 | |

| 3 | 42.2%/57.8% | 1.01 (0.38–2.70) | 0.981 | |

| Comorbidity | 0.074 | 0.889 | ||

| None (Ref.) | 42.7%/57.3 | |||

| Yes | 56.7%/43.3 | 0.94 (0.42–2.13) | ||

| C-ErbB2 | 0.786 | |||

| Negative (Ref.) | 46.6%/53.4% | |||

| Positive | 48.9%/51.1 | |||

| Chemotherapy History | 0.013 | 0.006 | ||

| None (Ref.) | 66.7%/33.3 | |||

| Yes | 42.9%/57.1% | 3.75 (1.46–9.69) | ||

| History of Radiotherapy | 0.597 | |||

| None (Ref.) | 42.3%/57.7 | |||

| Yes | 47.9%/52.1 | |||

| Type of Hormone Therapy | 0.025 | 0.290 | ||

| Tamoxifen (Ref.) | 36.6%/63.4 | |||

| Aromatase Inhibitor | 53.3%/56.7 | 1.85 (0.59–5.77) | ||

| OFS Use | 0.002 | 0.003 | ||

| None (Ref.) | 54.4%/45.6% | |||

| Yes | 29.1%/70.9% | 3.29 (1.51–7.15) | ||

| Educational Status | 0.493 | |||

| Primary-Secondary School | 49.5%/50.5 | |||

| High School-Undergraduate-Graduate | 44.4%/55.6 | |||

| Marital Status | 0.243 | 0.108 | ||

| Married (Ref.) | 44.3%/55.7 | |||

| Single/Widowed | 53.6%/46.4 | 0.55 (0.26–1.14) | ||

| Employment Status | 0.661 | |||

| Employed (Ref.) | 44.2%/45.8 | |||

| Not actively working | 48.0%/52.0 | |||

| Receiving Psychological Support | 0.022 | 0.087 | ||

| None (Ref.) | 51.3%/48.7% | |||

| Yes | 30.8%/69.2% | 2.09 (0.90–4.87) | ||

| Visiting a Non-Physician Healthcare Professional | 0.609 | |||

| No (Ref.) | 46.5%/53.5 | |||

| Yes | 52.4%/47.6 | |||

| Report Side Effects to Your Doctor | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| No (Ref.) | 66.3%/33.7 | |||

| Yes | 30.8%/69.2% | 3.52 (1.80–6.88) | ||

| Herbal Product/Alternative Medicine Application | 0.007 | 0.011 | ||

| No (Ref.) | 50.3%/49.7 | |||

| Yes | 16.7%/83.3% | 7.27 (1.57–33.63) | ||

| Univariate Analyses | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Symptom Burden Score (Low/High) | p Value | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | p Value | |

| Age | 0.07 | 0.227 | ||

| ≤50 (Ref.) | 52.9%/47.1% | |||

| >50 | 38.8%/61.2% | 1.52 (0.77–2.97) | ||

| Menopausal Status | 0.177 | 0.690 | ||

| Postmenopausal (Ref.) | 39.8%/60.2% | |||

| Pre-Perimenopause | 50.7%/49.3% | 0.81 (0.29–2.25) | ||

| Stage | 0.334 | |||

| 1 (Ref.) | 37.8%/62.2% | |||

| 2 | 50.0%/50.0% | 0.53 (0.25–1.10) | 0.086 | |

| 3 | 44.4%/55.6% | 0.63 (0.28–1.44) | 0.272 | |

| Comorbidity | 0.876 | |||

| None (Ref.) | 43.5%/56.5 | |||

| Yes | 45.0%/55.0 | |||

| C-ErbB2 | 0.732 | |||

| Negative (Ref.) | 43.2%/56.8 | |||

| Positive | 46.7%/53.3 | |||

| Chemotherapy History | 0.816 | |||

| None (Ref.) | 42.4%/57.6 | |||

| Yes | 44.2%/55.8 | |||

| History of Radiotherapy | 0.853 | |||

| No (Ref.) | 42.3%/57.7 | |||

| Yes | 44.2%/55.8 | |||

| Type of Hormone Therapy | 0.815 | |||

| Tamoxifen (Ref.) | 45.1%/54.9 | |||

| Aromatase Inhibitor | 43.3%/56.7 | |||

| OFS Use | 0.630 | |||

| None (Ref.) | 42.6%/57.4 | |||

| Yes | 47.3%/52.7 | |||

| Education | 0.378 | 0.630 | ||

| Primary-Secondary School | 41.1%/58.9 | |||

| High School-Undergraduate-Graduate | 47.8%/52.2 | 1.19 (0.59–2.40) | ||

| Marital Status | 0.107 | 0.176 | ||

| Married (Ref.) | 39.7%/60.1 | |||

| Single/Widowed | 53.6%/46.4 | 0.62 (0.31–1.24) | ||

| Employment Status | 0.601 | |||

| Employed (Ref.) | 39.5%/60.5 | |||

| Not actively working | 45.3%/54.7% | |||

| Receiving Psychological Support | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||

| None (Ref.) | 38.0%/62.0 | |||

| Yes | 69.2%/30.8% | 0.36 (0.19–0.67) | ||

| Visiting a Non-Physician Healthcare Professional | 0.817 | |||

| No (Ref.) | 43.5%/56.5 | |||

| Yes | 47.6%/52.4 | |||

| Reporting Side Effects to Doctor | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| No (Ref.) | 30.2%/69.8% | |||

| Yes | 54.8%/45.2% | 0.28 (0.13–0.64) | ||

| Herbal Product/Alternative Medicine Application | 0.327 | 0.181 | ||

| No (Ref.) | 42.8%/57.2 | |||

| Yes | 55.6%/44.4% | 0.47 (0.16–1.42) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ulukal Karanci, E.; Güzel, H.G.; Öztürk, B. Symptom Reporting Behaviors, Symptom Burden, and Quality of Life in Patients with Hormone Receptor–Positive Breast Cancer Undergoing Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32110599

Ulukal Karanci E, Güzel HG, Öztürk B. Symptom Reporting Behaviors, Symptom Burden, and Quality of Life in Patients with Hormone Receptor–Positive Breast Cancer Undergoing Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(11):599. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32110599

Chicago/Turabian StyleUlukal Karanci, Ece, Halil Göksel Güzel, and Banu Öztürk. 2025. "Symptom Reporting Behaviors, Symptom Burden, and Quality of Life in Patients with Hormone Receptor–Positive Breast Cancer Undergoing Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy" Current Oncology 32, no. 11: 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32110599

APA StyleUlukal Karanci, E., Güzel, H. G., & Öztürk, B. (2025). Symptom Reporting Behaviors, Symptom Burden, and Quality of Life in Patients with Hormone Receptor–Positive Breast Cancer Undergoing Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy. Current Oncology, 32(11), 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32110599