Understanding the Food Insecurity and Coping Strategies of Indigenous Households during COVID-19 Crisis in Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Ethical Approval

3.2. Study Area and Location

3.3. Sample Size, Data Collection, and Instruments

3.4. Data Analysis Procedures, Approaches of Taking Measurements, and Coding

4. Results

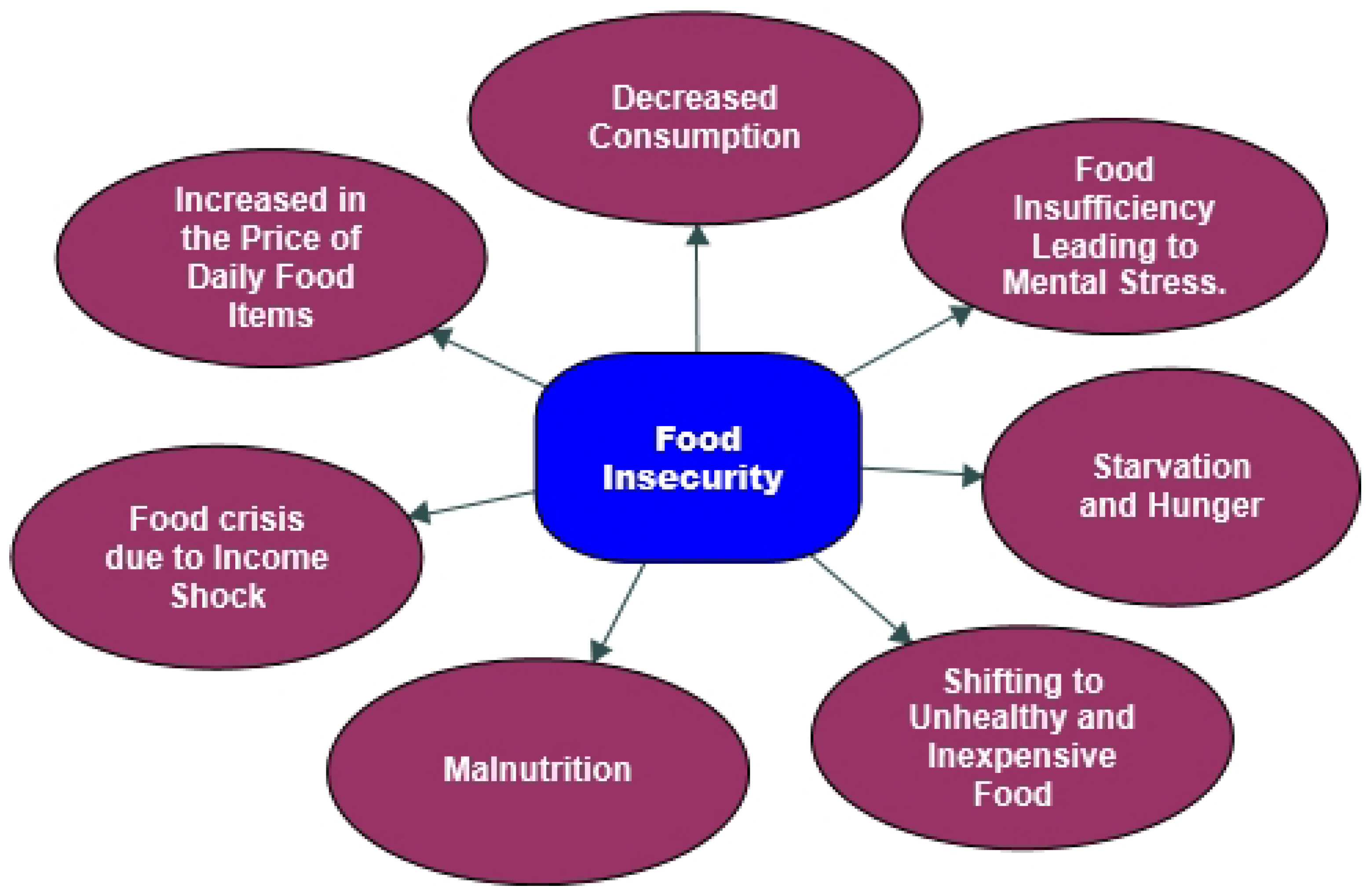

4.1. Food Insecurity

4.1.1. Decreased Food Consumption

“We had to reduce our consumption due to the pandemic. We had no income and sat idly at home during the lockdowns. We ate what we had at home”(Interviewee #10)

“Before the lockdown, I had access to three meals daily. During the 2nd lockdown, food availability was limited. I eat twice a day, one kg of pulses. Markets were inaccessible for buying or selling goods. When there are opportunities to sell, it is impossible to get a fair price. Goods are sold at low prices”(Interviewee #6)

4.1.2. The Increased Price of Food Items

“When the government imposed the 1st nationwide lockdown, there was a massive food crisis in the market with a limited number of goods. This imposition caused an increase in foods price relative to food supplies”(Interviewee #16)

“I have a grocery shop. All types of transport services were shut down due to the lockdown. I have to contact a local delivery agency to hire a vehicle to transport goods. They overcharged us for their services”(Interviewee #5)

“We had no oil in the house; cooking was impossible. Grocery stores open at certain times of the day. I couldn’t go to the store due to my busy schedule. Also, the shops were closed, so we had to buy inflated goods at a high price secretly. Isn’t that a problem?”(Interviewee 1)

4.1.3. Food Crisis due to Income Shock

“My son worked as a store manager in Dhaka. He lost his job due to the lockdown. We worried about this. We can hardly afford food due to our poor economic condition”(Interviewee #23)

“My trade business has been closed since the first lockdown limiting income-earning capacity. I have been doing this job since childhood. Now, I cannot continue the business. The job market is failing, and I have been living on my savings. Before the lockdown, I ate fish and meat almost every day. Now I cannot buy fish anymore. I have a meager budget for food”(Interviewee #8)

4.1.4. Malnutrition

“Police did not allow us to go outside nor go to work. I ate pulses for many days and could not afford nutritious food because I had no money”(Interviewee #24)

“My child often cried continuously due to inconsistent breastfeeding. No milk didn’t come in my breast because I was starved very often”(Interviewee #19)

4.1.5. Shifting to Cheap and Unhealthy Food

“This is so embarrassing, but the truth is that I had no money. So, I bought rotten vegetables and rice. During the whole lockdown, I preferred cheap food.”(Interviewee #7)

“Cheap and semi-rotten foods are less expensive than fresh foods. It is the perfect option for me in this crisis. I do not have enough money or savings. Hence, the only option was to survive by eating semi-rotten food. It does not matter whether it is wrong or good for health”(Interviewee #9)

“Mashed potatoes, snails, and mussels were in my food chart during the lockdown because it was cheap“(Interviewee #33)

4.1.6. Starvation and Hunger

“My husband died two years ago. Now, I have to work for survival. But I can only afford to eat a simple morning breakfast during the COVID-19 quarantine. I cannot afford to have proper three times meals daily. I am worried about starvation”(Interviewee #50)

“I can’t afford to eat properly. Sometimes, particularly in the first lockdown, I just drink water to fill my stomach “(Interviewee #48)

“Most tribal families in the hill areas are poor and have more or fewer food problems. But COVID-19 exacerbated the food crisis. In my case, some days, I remained starved and hungry during the lockdown. I cannot request food from anyone. I feel shy. That’s why I suffered more”(Interviewee # 29)

4.1.7. Food Insufficiency Leads to Mental Stress

“Lockdowns have destroyed our normal life. I have no income, employment, and no food in my house. I don’t bother about myself but worry about my kids and wife. Day by day, the mental stress is increasing”(Interviewee# 50)

“Sometimes I feel like committing suicide. The lockdown sent me into depression, especially when I had to cater to a family of five with no husband to provide support. Before the lockdown, I used to sell street foods. But now I can’t do it because of the government’s strict restrictions. My child cries for food. I don’t know when the lockdown will be lifted. We live in a remote hilly, and hard-to-reach area. It is challenging to receive food assistance here”(Interviewee #23)

4.2. Indigenous Coping Strategies during COVID-19

4.2.1. Taking Loans and Borrowing Foods

“I had to borrow one lakhs money from Janata bank and relatives. Having no income for such a long-time (6/7 months), I had to take loans to maintain the family. But I have not been able to repay the loan with reduced income. I spend a large amount of money monthly. It is challenging to repay loans because of the daily expenses”(Interviewee #36)

“I had no income, no money, and food at home. I stayed for a few days without food, and didn’t want to die because my wife and three children rely on me. So, I had to borrow food from my relatives”(Interviewee #39)

“I approached some people to borrow foodstuff, but none of them were able to give me. I hardly borrow paddy from a neighbor. But now, I am tense about paying them back. I am not certain my situation can improve in the future”(Interviewee #21)

4.2.2. Reducing Expenses

“I had to reduce my budget for food because I could not afford three meals daily”(Interviewee #23)

“Usually, we eat fish and meat at least two days a week. Now, to cope with the food situation, I do not buy fish anymore”(Interviewee #8)

“My income is quite low. I could only afford green vegetables and no other food items”(Interviewee #60)

4.2.3. Changing Food Habits

“Before the outbreak, I used to eat three times, and now I have to eat twice a day one kg of pulses”(Interviewee #57)

“Before lockdown, I could purchase meat. Now, meat and Fish are unaffordable with my current income. I mostly now eat hill potatoes or pulses with rice twice daily during the lockdown“(Interviewee #2)

4.2.4. Selling Domestic Animals and Property

“Yes, I had to sell chickens and goats since I was unable to repay all the loans”(Interviewee #17)

“The only way to earn money is to drive a tomtom (autorickshaw). I had to sell my tomtom. Before the pandemic, I had three tomtoms; now, there is only one. I had to sell the other two because of the food crisis”(Interviewee #56)

“We had to sell our cows and goat. Due to the food shortage, we had to sell them cheaply”(Interviewee #38)

4.2.5. Collecting Forest and Hills Foods

“I collected cauliflowers (a popular hill vegetable) from local forests as it was an easy food option”(Interviewee #6)

“Our homes are located near the hills. Therefore, my brother and I gathered beans and sweet potatoes daily since it was tough for us to go to the market or afford high-priced food”(Interviewee #33)

“I used to sell clothes at my shop near Jogonnath Mondir(temple). But, after the lockdown, we had to shut down our shops and could not get out for months. I collected beans, green jack fruits, and seeds from the forest”(Interviewee #22)

4.2.6. Social and Governmental Reliefs

“They couldn’t provide everything we needed, but they tangibly supported us. I am satisfied. I don’t know the names of the organization, but they supported us along with some rich individuals”(Interviewee #60)

“The chairman donated rice, pulses, and oil twice during the lockdowns. He donated in the first lockdown and second lockdown. They engaged the military in arranging the market in the stadium. Army personnel gave me the slip, and I went there to get rice, pulses, arums, and cucumber”(Interviewee #57)

“I was sitting in the yard here. A few Tripura young people came and gave us 5 kg of cooked rice once. Our relatives gave some rice, pulses, and oil. We got those twice during the lockdowns”.(Interviewee #3)

5. Discussion

5.1. Policy Recommendations

5.2. Strength and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chriscaden, K. Impact of COVID-19 on People’s Livelihoods, Their Health and Our Food Systems; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sohel, M.S.; Hossain, B.; Sarker, M.N.I.; Horaira, G.A.; Sifullah, M.K.; Rahman, M.A. Impacts of COVID-19 induced food insecurity among informal migrants: Insight from Dhaka, Bangladesh. J. Public Aff. 2021, 11, e2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Food Program. WFP Global Update on COVID-19: November 2020; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WFP. COVID-19 Will Double Number of People Facing Food Crises Unless Swift Action Is Taken; World Food Programme: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Oxfam International. A Rapid Assessment Report: The impact of COVID-19 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Bangladesh; IWGIA–International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021; Available online: https://www.iwgia.org/en/bangladesh/3863-kapaeeng-covid-19-ra.html (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- United Nations. Food & United Nations; After remaining virtually unchanged from, world faced hunger in 2020; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/food#:~:text= (accessed on 27 June 2021).

- Africa Hunger, Famine: Facts, FAQs, and How to Help. In World Vision. 2021. Available online: https://www.worldvision.org/hunger-news-stories/africa-hunger-famine-facts (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Rashid, S.F.; Theobald, S.; Ozano, K. Towards a socially just model: Balancing hunger and response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.; Oliveira, A.M. Poverty and food insecurity may increase as the threat of COVID-19 spreads. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 3236–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukari, C.; Aning-Agyei, M.A.; Kyeremeh, C.; Essilfie, G.; Amuquandoh, K.F.; Owusu, A.A.; Otoo, I.C.; Bukari, K.I. Effect of COVID-19 on Household Food Insecurity and Poverty: Evidence from Ghana. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 159, 991–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kansiime, M.K.; Tambo, J.A.; Mugambi, I.; Bundi, M.; Kara, A.; Owuor, C. COVID-19 implications on household income and food security in Kenya and Uganda: Findings from a rapid assessment. World Dev. 2020, 137, 105199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bilali, H.; Ben Hassen, T.; Baya Chatti, C.; Abouabdillah, A.; Alaoui, S.B. Exploring Household Food Dynamics during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Morocco. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, L.; Murray, L. Children and Covid 19 in the UK. Taylor Fr. 2021, 20, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmet, A.; Stroebele-Benschop, N. Food Bank Operations during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2021, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, K. How Has COVID-19 Impacted Food Security in the US? World Economic Forum. 2021. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/09/united-states-us-food-insecurity-covid-pandemic-lockdown-coronavirus/ (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Dondi, A.; Candela, E.; Morigi, F.; Lenzi, J.; Pierantoni, L.; Lanari, M. Parents’ Perception of Food Insecurity and of Its Effects on Their Children in Italy Six Months after the COVID-19 Pandemic Outbreak. Nutrients 2020, 13, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golunov, S.; Smirnova, V. Russian Border Controls in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Social, Political, and Economic Implications. Probl. Post-Communism 2021, 69, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, R.M. Changes in the food-related behaviour of italian consumers during the covid-19 pandemic. Foods 2021, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, L. Final Report for Eight Assembly of First Nations Regions. Assembly of First Nations, University of Ottawa, Université de Montréal, Canada. 2019. Available online: https://www.fnfnes.ca/docs/FNFNES_draft_technical_report_Nov_2__2019.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Cupertino, G.A.; do Carmo Cupertino, M.; Gomes, A.P.; Braga, L.M.; Siqueira-Batista, R. COVID-19 and Brazilian indigenous populations. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN. UN/DESA Policy Brief #70: The Impact of COVID-19 on Indigenous Peoples. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2021. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/un-desa-policy-brief-70-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-indigenous-peoples/ (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- ILO. COVID-19 and the world of work: A focus on indigenous and tribal peoples, Policy Brief. Pancanaka 2020, 1, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, P.; Deshwara, M.; Ethnic Population in 2022 Census: Real Picture Not Reflected. The Daily Star. 2022. Available online: https://www.thedailystar.net/news/bangladesh/news/ethnic-population-2022-census-real-picture-not-reflected-3090941 (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Jamil, I.; Panday, P.K. The elusive peace accord in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh and the plight of the indigenous people. Commonw. Comp. Polit. 2008, 46, 464–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruk, M.O.; Ching, U.; Chowdhury, K.U.A. Mental health and well-being of indigenous people during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, G. A Strategic Framework for Sustainable Development in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh; ICIMOD Working Paper; International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development: Lalitpur, Nepal, 2015; pp. x + 17. Available online: http://lib.icimod.org/record/31134/files/WP_2015_3.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- Ali, H.M.A.; Vallianatos, H. Women’s Experiences of Food Insecurity and Coping Strategies in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2017, 56, 462–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkat, A.; Halim, S. Baseline Survey of Chittagong Hill Tracts. Methodology. UNDP. 2009. Available online: http://www.hdrc-bd.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/6.-Socio-economic-Baseline-Survey-of-Chittagong-Hill-Tracts.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Kirstyn, M. Covid-19 Exacerbates Food Insecurity for Indigenous Peoples. International Bar Association. 2021. Available online: https://www.ibanet.org/article/D36C40DA-C2CA-4E1C-94AB-557CB1BF648F (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- Shibli, A. Food Insecurity Increases Amidst the Latest Covid-19 Spike. 2021. Available online: https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/open-dialogue/news/food-insecurity-increases-amidst-the-latest-covid-19-spike-2087621 (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Trimita Chakma, P.C. Still Left behind: Covid-19 and Indigenous Peoples of Bangladesh. The Daily Star. 2020. Available online: https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/news/still-left-behind-covid-19-and-indigenous-peoples-bangladesh-1941817 (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Rabbi, M.F.; Oláh, J.; Popp, J.; Máté, D.; Kovács, S. Food security and the covid-19 crisis from a consumer buying behaviour perspective—The case of Bangladesh. Foods 2021, 10, 3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottaleb, K.A.; Mainuddin, M.; Sonobe, T. COVID-19 induced economic loss and ensuring food security for vulnerable groups: Policy implications from Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobarok, M.H.; Thompson, W.; Skevas, T. COVID-19 and policy impacts on the Bangladeshi rice market and food security. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, V.; Grépin, K.A.; Rabbani, A.; Navia, B.; Ngunjiri, A.S.W.; Wu, N. Food insecurity and COVID-19 risk in low- and middle-income countries. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2022, 44, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Islam, A.; Pakrashi, D.; Rahman, T.; Siddique, A. Determinants and dynamics of food insecurity during COVID-19 in rural Bangladesh. Food Policy 2021, 101, 102066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.C.; Boidya, P.; Haque, M.I.M.; Hossain, A.; Shams, Z.; Mamun, A. Al The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fish consumption and household food security in Dhaka city, Bangladesh. Glob. Food Sec. 2021, 29, 100526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, S.; Al Banna, M.H.; Sayeed, A.; Sultana, M.S.; Brazendale, K.; Harris, J.; Mandal, M.; Jahan, I.; Abid, M.T.; Khan, M.S.I. Determinants of household food security and dietary diversity during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Rasul, M.G.; Hossain, M.S.; Khan, A.-R.; Alam, M.A.; Ahmed, T.; Clemens, J.D. Acute food insecurity and short-term coping strategies of urban and rural households of Bangladesh during the lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic of 2020: Report of a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e043365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, G.M.M.; Khatun, M.N. Impact of COVID-19 on vegetable supply chain and food security: Empirical evidence from Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruszczyk, H.A.; Rahman, M.F.; Bracken, L.J.; Sudha, S. Contextualizing the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on food security in two small cities in Bangladesh. Environ. Urban. 2021, 33, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syafiq, A.; Fikawati, S.; Gemily, S.C. Household food security during the COVID-19 pandemic in urban and semi-urban areas in Indonesia. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2022, 41, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John-Henderson, N.A.; Oosterhoff, B.J.; Johnson, L.R.; Ellen Lafromboise, M.; Malatare, M.; Salois, E. COVID-19 and food insecurity in the Blackfeet Tribal Community. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, D.X.; Morales, S.A.; Beltran, T.F. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Household Food Insecurity During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Nationally Representative Study. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2020, 8, 1300–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanova, E.; Andronov, S.; Morell, I.A.; Hossain, K.; Raheem, D.; Filant, P.; Lobanov, A. Food Sovereignty of the Indigenous Peoples in the Arctic Zone of Western Siberia: Response to COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimani, M.E.; Sarr, M.; Cuffee, Y.; Liu, C.; Webster, N.S. Associations of race/ethnicity and food insecurity with COVID-19 infection rates across US counties. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2112852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Mohan, S.B. The impact of food security disruption due to the Covid-19 pandemic on tribal people in India. In Advances in Food Security and Sustainability; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 6, pp. 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Salin, M.; Kaittila, A.; Hakovirta, M.; Anttila, M. Family coping strategies during finland’s COVID-19 lockdown. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, H.M.; Supple, A.J.; Proulx, C.M. Mexican-Origin Couples in the Early Years of Parenthood: Marital Well-Being in Ecological Context. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2011, 3, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mantel, S.; Khan, M. Chittagong Hill Tracts Improved Natural Resource Management. In Proceedings of the National Workshop held in Rangamati, Rangamati, Bangladesh, 15–16 February 2006; CHARM Project Report 1. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/17025 (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Sandelowski, M. Qualitative analysis: What it is and how to begin. Res. Nurs. Health 1995, 18, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, M.; McKenzie, H. The logic of small samples in interview-based qualitative research. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2006, 45, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, K. Business Statistics For Contemporary Decision Making, 6th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Available online: http://staffnew.uny.ac.id/upload/197907162014041001/pendidikan/referensi-statistic-cp1.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Dawson, S.; Manderson, L.; Tallo, V.L. Methods for Social Research in Disease. A Manual for the Use of Focus Groups; International Nutrition Foundation for Developing Countries: Boston, MA, USA, 1993; p. 96. Available online: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/41795 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 8th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2012; Available online: https://www.pearson.com/us/higher-education/product/Berg-Qualitative-Research-Methods-for-the-Social-Sciences-8th-Edition/9780205809387.html (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Denzin, N. An Introduction to Triangulation; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/sub_landing/files/10_4-Intro-to-triangulation-MEF.pdf. (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Available online: http://eli.johogo.com/Class/Qualitative-Research.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Pölkki, T.; Utriainen, K.; Kyngäs, H. Qualitative Content Analysis. SAGE Open 2014, 4, 215824401452263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muellbauer, J. The Coronavirus Pandemic and US Consumption.VOX, CEPR, Centre for Economic Policy Research. 2020. Available online: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/coronavirus-pandemic-and-us-consumption (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Pan, D.; Yang, J.; Zhou, G.; Kong, F. The influence of COVID-19 on agricultural economy and emergency mitigation measures in China: A text mining analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuit, C.K.; On, P.A. Counting the Cost as New COVID-19 Waves Disrupt Supply Chains in Asia; CNA: Singapore, 2021; Available online: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/business/supply-chain-disruptions-asia-costs-consumers-money-mind-1934071 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- UNCTAD. Shipping during COVID-19: Why Container Freight Rates Have Surged; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: 2021. Geneva, Switzerland. Available online: https://unctad.org/news/shipping-during-covid-19-why-container-freight-rates-have-surged (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Akter, S.; Basher, S.A. The impacts of food price and income shocks on household food security and economic well-being: Evidence from rural Bangladesh. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 25, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Islam, A.; Rahman, A.; Nisat, R. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Small and Medium Enterprises in Bangladesh; Development Economics Series 01; Report No.: 62; BIGD: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Malnutrition Hangs on Hill Districts. The Asian Age. 2016. Available online: https://dailyasianage.com/news/42994/malnutrition-hangs-on-hill-districts (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- The World Bank. Food Security and COVID-19; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/brief-food-security-and-covid-19 (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Hansen, T. How Covid-19 Could Destroy Indigenous Communities-BBC Future. Available online: :https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200727-how-covid-19-could-destroy-indigenous-communities (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Reid, K. 10 World Hunger Facts You Need to Know. 2022. Available online: https://www.worldvision.org/hunger-news-stories/world-hunger-facts (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Al Jazeera. World Hunger Rising as UN Agencies Warn of ‘Looming Catastrophe’. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/7/6/world-hunger-rising-as-un-agencies-warn-of-looming-catastrophe (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Rozario, S.U. Ethnic Communities Face Starvation in Bangladesh. 2020. Available online: https://www.ucanews.com/news/ethnic-communities-face-starvation-in-bangladesh/87768 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Fang, D.; Thomsen, M.R.; Nayga, R.M. The association between food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, B.; Shi, G.; Ajiang, C.; Sarker, N.I.; Sohel, S.; Sun, Z.; Hamza, A. Impact of climate change on human health: Evidence from riverine island dwellers of Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, B.; Ryakitimbo, C.M.; Sohel, M.S. Climate Change Induced Human Displacement in Bangladesh: A Case Study of Flood in 2017 in Char in Gaibandha District. Asian Res. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 2020, 10, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hossain, B.; Sohel, M.S.; Ryakitimbo, C.M. Climate change induced extreme flood disaster in Bangladesh: Implications on people’s livelihoods in the Char Village and their coping mechanisms. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 6, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, B.; Sarker, N.I.; Sohel, S. Assessing the Role of Organizations for Health Amenities of Flood Affected People in Char Areas of Bangladesh; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, T.L. The social ecology of marriage and other intimate unions. J. Marriage Fam. 2000, 62, 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A. “One Meal a Day”: How Pandemic Hit Families before Unicef’s Aid. The Guardian. 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/dec/18/one-meal-a-day-how-pandemic-hit-families-before-unicefs-aid (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Sohel, M.S.; Hossain, B.; Alam, M.K.; Shi, G.; Shabbir, R.; Sifullah, M.K.; Mamy, M.M.B. COVID-19 induced impact on informal migrants in Bangladesh: A qualitative study. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2021, 42, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf Ali, H.M.; Vallianatos, H. Indigenous foodways in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh: An alternative-additional food network. In Postcolonialism, Indigenity and Struggles for Food Sovereignty: Alternative Food Networks in Subaltern Spaces; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; pp. 34–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.H.; Alam, K. Forest dependent indigenous communities’ perception and adaptation to climate change through local knowledge in the protected area-A Bangladesh Case Study. Climate 2016, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miah, M.D.; Chakma, S.; Koike, M.; Muhammed, N. Contribution of forests to the livelihood of the Chakma community in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh. J. For. Res. 2012, 17, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, C. Indigenous Food Systems Prove Highly Resilient during COVID-19; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Leweniqila, I.; Vunibola, S. Food Security in COVID-19: Insights from Indigenous Fijian Communities. Oceania 2020, 90, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakravan-Charvadeh, M.R.; Savari, M.; Khan, H.A.; Gholamrezai, S.; Flora, C. Determinants of household vulnerability to food insecurity during COVID-19 lockdown in a mid-term period in Iran. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 1619–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, A.; Cini, E. Will the COVID-19 pandemic make us reconsider the relevance of short food supply chains and local productions? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 99, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food in a time of COVID-19. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 429. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akter, S. The impact of COVID-19 related ‘stay-at-home’ restrictions on food prices in Europe: Findings from a preliminary analysis. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. The Impact of COVID-19 on Indigenous Peoples. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/PB_70.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Hossain, B.; Shi, G.; Ajiang, C.; Sarker, M.N.I.; Sohel, M.S.; Sun, Z.; Yang, Q. Climate change-induced human displacement in Bangladesh: Implications on the livelihood of displaced riverine island dwellers and their adaptation strategies. Front. Psychol. 2022, 5975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Amin, A.; Mohan, S.B.; Mohan, P. Food Insecurity in Tribal High Migration Communities in Rajasthan, India. Food Nutr. Bull. 2020, 41, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indigenous Food Systems Are at the Heart of Resilience; International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD): Rome, Italy, 2021.

- Levkoe, C.Z.; McLaughlin, J.; Strutt, C. Mobilizing Networks and Relationships Through Indigenous Food Sovereignty: The Indigenous Food Circle’s Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Northwestern Ontario. Front. Commun. 2021, 6, 672458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombia: Indigenous Kids at Risk of Malnutrition, Death; Human Rights Watch: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Galali, Y. The impact of COVID-19 confinement on the eating habits and lifestyle changes: A cross sectional study. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 2105–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, K.; de Brauw, A.; Abate, G.T. Food Consumption and Food Security during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Addis Ababa. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2021, 103, 772–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J. 14 Countries that Are Paying Their Workers during Quarantine—And How They Compare to America’s $1200 Stimulus Checks. Insider. 2020. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/countries-offering-direct-payments-or-basic-income-in-corona-crisis-2020-4 (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Sohel, S.; Azimul, S.; Noshin, E.; Zaman, T. Understanding rural local government response during COVID-19-induced lockdown: Perspective from Bangladesh. SN Soc. Sci. 2022, 0123456789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Methodology and Sample Size | Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| [32] | Multivariate Multiple Ordinal Logit Regression, partial least squares path model with n = 540 | Higher COVID-19 severity correlating to starvation because of income shock and price hike, and food insecurity affecting purchasing and consuming patterns | Negative weights, multicollinearity, unavailability of global index for model validation, limited use of goodness-of-fit |

| [33] | OLS approach with n = 50,000 | Estimation of the economic damage caused by the COVID-19-induced lockdown and proposed a minimal financial package to maintain food security for Bangladesh’s daily paid workers | Lack of theoretical discussion |

| [34] | Multi-equation partial equilibrium with rice market data from FY96 to FY20 | Decrease in food security, higher import tariff limiting rice supply and stock enhancement strategy mitigating the negative impact | Absence of the influence of economy-wide imbalances on the Bangladeshi rice market, and the dynamics in relation to other agricultural and non-agricultural sectors |

| [35] | Longitudinal study with 3544 persons Bangladesh, 3685 persons in Kenya, and 3582 persons in Nigeria | Unemployment, shutdown of business, disruption in agricultural activities, price hike, sickness/death, selling assets, extra earning, monetary support, decrease food/non-food intake, savings | No mention about most vulnerable demographic groups, and reasons of inequalities, no discussion whether job loss and business shutdown related to labor demand/supply, no theoretical framework |

| [36] | Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES), linear probability model, 10,000 households | Food insecurity increased dramatically across families and began to impact groups that were in a better situation in the first survey | Phone interview, two study areas, no discussion on the issue of endogeneity under various data and interview constraints, lack of exogenous fluctuations, no theoretical linking |

| [37] | Descriptive statistics, n = 397 | Income shock, unemployment, price hike, reducing grocery shopping, high-cost goods and unhealthy snacks, intaking nutrient food, adopted eggs and dried fish and stored rice, lentils and potatoes | Absence of theoretical framework, missing answers to some questions, the number of participants for different indicators was not the same |

| [38] | Cross-sectional survey, n = 1876 | Decrease in consumption, job lost, or shut down businesses, income shock | Lack of theoretical discussion, short time frame—5 months, online participants, unable to assess any seasonal fluctuation in HFS and HDD, self-reported data by the participants |

| [2] | Interpretive phenomenological analysis, 21 in-depth interviews and 4 FGDs | Skipping meals, rising prices, and a scarcity of fish, meat, potatoes, and vegetables, chronic nutritional scarcity, hunger, maternal and child malnutrition, and cheap food. | Limited to informal migrants in Dhaka city, small sample size |

| [39] | Cross-sectional survey, 106 urban and 106 rural households | Selling or crediting property, lending food and money, reducing food quality and amount | Lack of theoretical dimension, short study timeline |

| [40] | Gross margin analysis, n = 120 | Disruption of supply chain, income loss, limiting access to market, and productional capacity, reduction in vegetables’ cultivation, declined food consumption | No theoretical dimension, only focused on vegetables supply and food security, farmers as respondents |

| [41] | Empirical work, n = 201 | Shift in food intake and diet, drop in household income, stockpiling food, skipping food or reducing consumption, raising the amount of budget allotted to food, getting food aid, borrowing | Limited to nine weeks lockdown, no discussion on the role of NGO or government, no theoretical discussion |

| Reference/Sources | Study Area | Methodology and Sample Size | Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [42] | Indonesia | Cross-sectional study with n = 517 | Household Income loss, closure of work, high food insecurity in low-income families and houses comprising a younger member | Online interviews, less variation in socio- demographic profile, no theoretical implication, and inability to use conventional food consumption instruments |

| [43] | USA | Longitudinal study and Food Security Survey Module (FSSM) with n = 167 | Women were more likely to have food insecurity, were less capable of affording proper meals, ended up eating smaller portions, and were more likely to starve than men | Lack of theoretical link, and missing discussion on Blackfeet tribal community’s coping strategies during COVID-19 |

| [44] | USA | Cross-sectional study, n = 74,413 | Households headed by Asian, Black, Hispanic, or other racial minorities were not remarkably more food insecure than White households | Main focus on food access, no discussion on the nutritional consequences of food insecurity, cross-sectional research design and week-one HPS microdata, absence of theoretical dimension |

| [45] | Arctic zone of Western Siberia | Multidisciplinary approach, n = 252 | Insufficient access to local food, vaccines and medicines, rise in production cost, reduction in selling reindeer products’ price, change in food diet, health risk | Missing theoretical dimension, limited numbers of participants in reindeer herding industry |

| [46] | USA | Cross-sectional study, 3133 US counties | Infection rates were higher in Black, American Indian, or Alaska Native group with higher food scarcity and vast populations | Absence of theoretical framework, no explanation about food assistances or support services, and policy measures |

| [47] | India | Cross-sectional study n = 211 | Barriers in getting ration, access to limited food items, starvation, lack of food supply | No theoretical framework, phone interview, short period |

| Steps | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Interview transcription | The interviews were taped and read again after hearing the recordings several times to comprehend their contents. |

| 2. Unit for the formation of meaning analysis | All interviews were analyzed as a single unit. Primary codes were created by abstracting the meaning units. |

| 3. Comprehensive sorting of similar codes | The grouping of similar fundamental codes into more comprehensive categories was conducted. |

| 4. Comparison of codes and establishment of subcategories | In contrast, all codes and data identified similarities and differences. This process resulted in the formation of categories and subcategories. |

| 5. Comparing subcategories and establishing primary categories | The initial interviews yielded an initial set of codes, categories, and subcategories, and the emerging codes were considered to be the results due to the thematic analysis approach. |

| Central Theme | Sub-Theme | Reference Code from NVivo-12 | Descriptive Coding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Insecurity | Decreased consumption | 88 | We had to reduce our consumption due to pandemic |

| Increase the price of daily food items | 67 | The shop was closed, so we had to buy urgent goods at a high price secretly. So, isn’t that a problem? | |

| Income shock to the food crisis | 64 | We have no income right now. We hardly afford our budget for food due to our poor condition | |

| Poor nutrition | 41 | The most difficult time for a mother is when she cannot feed her kids. I could not eat food properly, so there was no milk in my breast | |

| Shifting to unhealthy and inexpensive food | 36 | This is so embarrassing, but the truth is that I had no money during the lockdown. So, I bought rotten vegetables and rice. Even | |

| Starvation and hunger | 29 | I cannot afford to have two-times meal. I am worried about Starvation | |

| Food insufficiency leads to mental stress | 28 | The sensation of hunger is affecting my child’s mental health | |

| Coping Strategies | Taking loans and borrowing foods | 72 | I had to borrow about lakhs both from Janata bank and relatives. Having no income for such a long-time of 6/7 months, I had to take this money to run the family. |

| Reduced expenses and savings | 60 | We used to eat fish meat almost every day, two days in a week. Now to deal with the situation, I do not buy fish anymore. | |

| Changing food habits | 49 | Where I used to eat three times, then I had to eat twice a day with one kg of pulses. | |

| Collecting forest and hill foods | 44 | To feed my family, I collect beans, green jack fruits, seeds from the forest. | |

| Selling domestic animals and property | 29 | Before, I had three tomtoms; now, there is only one. I had to sell the other two due to the food crisis. | |

| Social and governmental reliefs | 25 | Apart from the chairman’s members, an organization was also cooperating from other places. I don’t know which organization it is. Besides, some rich people helped us. |

| Category | Variable | N |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 39 |

| Women | 21 | |

Age | 20–30 | 17 |

| 30–40 | 15 | |

| 40–50 | 11 | |

| 50–60 60–70 | 10 7 | |

| Education | Illiterate | 32 |

| Under Primary School | 13 | |

| Primary School | 9 | |

| High School | 6 | |

| Marital status | Married | 46 |

| Widow | 14 | |

| Ethnicity | Chakma | 24 |

| Marma | 18 | |

| Tripura | 9 | |

| Tanchangya | 9 | |

| Place of residence | Khagrachari | 20 |

| Rangamati | 20 | |

| Bandarban | 20 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sohel, M.S.; Shi, G.; Zaman, N.T.; Hossain, B.; Halimuzzaman, M.; Akintunde, T.Y.; Liu, H. Understanding the Food Insecurity and Coping Strategies of Indigenous Households during COVID-19 Crisis in Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh: A Qualitative Study. Foods 2022, 11, 3103. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11193103

Sohel MS, Shi G, Zaman NT, Hossain B, Halimuzzaman M, Akintunde TY, Liu H. Understanding the Food Insecurity and Coping Strategies of Indigenous Households during COVID-19 Crisis in Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh: A Qualitative Study. Foods. 2022; 11(19):3103. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11193103

Chicago/Turabian StyleSohel, Md. Salman, Guoqing Shi, Noshin Tasnim Zaman, Babul Hossain, Md. Halimuzzaman, Tosin Yinka Akintunde, and Huicong Liu. 2022. "Understanding the Food Insecurity and Coping Strategies of Indigenous Households during COVID-19 Crisis in Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh: A Qualitative Study" Foods 11, no. 19: 3103. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11193103

APA StyleSohel, M. S., Shi, G., Zaman, N. T., Hossain, B., Halimuzzaman, M., Akintunde, T. Y., & Liu, H. (2022). Understanding the Food Insecurity and Coping Strategies of Indigenous Households during COVID-19 Crisis in Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh: A Qualitative Study. Foods, 11(19), 3103. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11193103