The Architecture of Financial Networks and Models of Financial Instruments According to the “Just Transition Mechanism” at the European Level

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theories of Economic Growth

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Presentation of the Fair Transition Mechanism and How It Will Be Financed

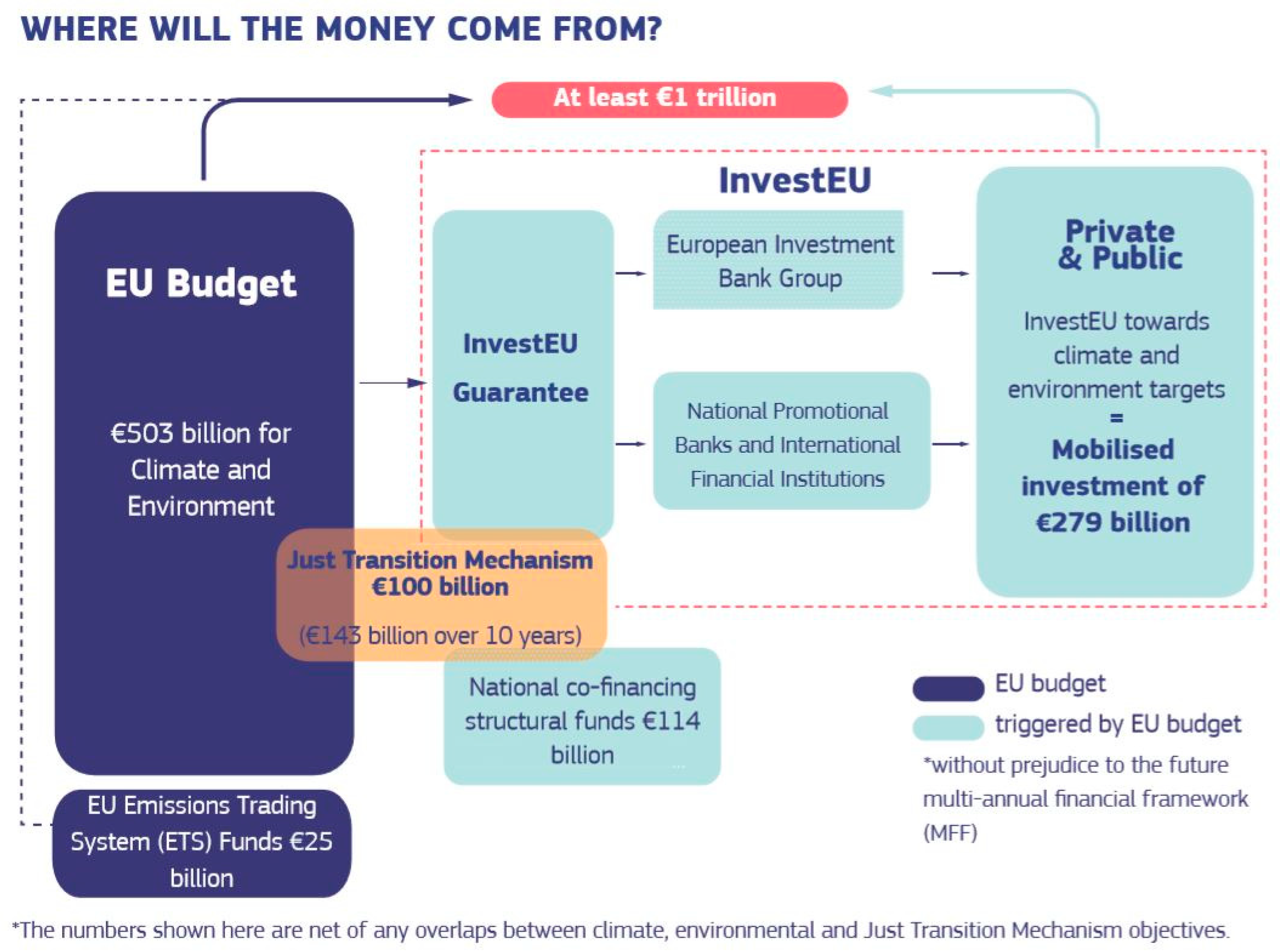

- The Green Deal investment plan. Member States will match each euro in the Fair Transition Fund with a minimum of €1.5 and a maximum of €3 from the European Regional Development Fund and the European Social Plus Fund. These resources from the EU budget will be further supplemented by national cofinancing according to the rules of cohesion policy. Taken together, the funding will reach between 30 and 50 billion euros in period 2021–2027. The fund will primarily provide subsidies to regions where many people work in coal, lignite, oil, and peat shale, or in regions that house greenhouse industries. For example, it will support workers to develop skills and competences for the job market of the future and SMEs, but also new economic opportunities for creating jobs in these regions. It will also support investments in clean energy transition––for example in energy efficiency.

- Transition scheme dedicated only to InvestEU to mobilize investments of up to 45 billion euros. This will attract private investments that will benefit these regions, as well as help their economies to find new sources of growth. For example, this could include decarbonization projects and the economic diversification of regions, energy, transport, as well as social infrastructure. The scheme will operate in accordance with the principles that define InvestEU, whereby part of the financing within InvestEU will be focused on fair transition objectives. The goal of generating up to 45 billion euros of investments corresponds to a supply of approximately 1.8 billion euros from the EU budget for the EU budget InvestEU program.

4.2. The Architecture of Financial Markets––Formalization

4.3. Financial Collector Network (RFC)

- (1)

- Bidders of availability (ODP), represented by households (GP), firms (FR), state (ST) and even financial institutions (IF). For methodological reasons, we did not consider “the outside”––that is, financial relations with the subjects from outside the country.

- (2)

- Collecting financial institutions (IFCs) that can be delimited according to two types of collection institutions (ISCs): banking institutions (IB) and nonbanking institutions (IN).

- from the bidder to the financial institutions, the availability collected by the latter (DSB);

- from financial institutions to bidders, the “price” of loans for deposits, debt securities, and interest rates (DBZ). Cash flows collected in the form of deposits also involve withdrawal flows from banking institutions to bidders, or from conversion into securities.

4.4. Financial Placement Network (PPF)

- from the financial institutions to the applicants for financial resources, especially the companies and the state, through the credits granted and the placement titles purchased on behalf of the bidders that the financial institution has collected;

- from the applicants for investments to the financial institutions where exist monetary flows through which the financial resources are reimbursed only to the due dates and at the same time the prices related to the placement instruments are paid.

- It is a risk that disturbs the interactivity of the network flows, affecting the force of the interactivity and of the active, distributive, and transitive transfers between the elements of the network, especially among its constituents: interactivity that gives the network individuality, potentiality and purpose.

- It is a risk that affects the interconnectivity of the network, its connections, the connections among the elements that allow and favor the realization of the interactivity, and the risk of decoupling, distortion, debilitation, and phase-out of these connections, and the interconnectivity contributing to network coherence, consistency and validity. This characteristic is materialized, for example, by affecting the interfaces and the nodes, the financial centers for coupling and connecting, and the monetary conversion operators.

Principles of the Process of Globalization of Financial Markets

- The principle of “increased exposure to political risk”: Banking financial institutions that extend across national borders increase the uncertainties they face.

- The principle of “increasing the activity of multinational companies”: Raising a larger community of standards and businesses beyond national borders, improved profits and market share can be achieved through mergers and acquisitions, faster than with conventional construction operations.

- The principle of “identifying new forms of competition and cooperation”: Financial institutions entering foreign markets will create new forms of competition.

- The principle of “new cultural sensitivities”: Global travel means improving efficiency and profitability by capitalizing on the world’s best available talent.

- The principle of “common virtual space”: As companies (including financial institutions) expand their geographical operations, managers are responsible for staff from different countries.

- The principle of “best practices”: Acting as a single company with a global, supranational culture excuses justifying the maintenance of national practices, which disappear.

- The principle of “alliances”: Globalization enables many new types of alliances.

- The principle of “finance”: Globalization leads to the harmonization of the functioning mechanism of the financial markets by uniformizing the levers, instruments, techniques, methods, and legal framework of operation.

- The principle of “globalization of suppliers”: a company’s decision to globalize its entire supply chain, which affects all the companies that provide services.

- The principle of “winners and losers in globalization”: While globalization will provide huge aggregate benefits to both producers and consumers, it will not provide these benefits equally.

- The principle of “returning from globalization”: the transition to globalization for countries will not be easy or smooth. Inevitably, a reaction will be generated against globalization that will organize and press the State to resist globalization if not reject it outright.

4.5. Financing and Economic Instruments

4.6. New Instruments That Should Be Developed in the Financial Markets, in Line with Sustainable Development

Concept of “Financing Green”: FinGreenTech

- a paradigm of economic growth that simultaneously pursues the environment’s growth and improvement;

- stimulation of economic growth and job creation through research and development in the field of clean energy and green technologies;

- conservation and efficient use of energy and resources;

- mitigation of climate change and environmental.

4.7. Green Technology

The Need to Develop the New Concept of Green Financing––FinGreenTech

5. Discussion

- There is a period of continuous economic growth, despite a slowdown in rhythm. There is also synchronization of economic cycles, which also proves that what we call connectivity is intense in the global space and not in the chain of “production chains.” However, the global economy also has major vulnerabilities, and connectivity itself is a systemic risk.

- Protectionist tendencies pose a great danger by adding to the use of exchange rates as means of stimulating exports (to support the domestic economic activity). A trade war is no longer a hypothetical risk, and we see the amount of uncertainty increasing (as the IMF also warns). This danger adds to Brexit and Italy’s risk in the Euro area.

- A narrowing of the nonstandard operations of large central banks (the EDF in particular) can be observed as a result of inflationary pressures and the desire to limit the undesirable effects of these operations. However, normalization will be very gradual, especially in Europe.

- Even if “normalization” of monetary policies is gradual, shocks will be felt by the more vulnerable emerging economies through capital flight and increasing margins on loans. In this context, there is the danger of “syncope of access to liquidity” for economies that have large debts (especially external) and internal deficits.

- In today’s uncertain global climate, Europe needs a monetary union that can withstand future economic shocks and enable the euro to play a stronger international role.

- Significant progress must be made in reducing risks in the banking sector and reducing the rate of nonperforming loans in European banks.

- Financial stability in the EU has been considerably strengthened, and risks for the banking sector continue to decline. In particular, for one year (2017), the average rate of nonperforming loans in the EU decreased by 1.2% in 2017 compared with 2016, so that it reached 3.4%. In Croatia, Cyprus, Hungary, Ireland, Portugal, and Slovenia, there were even decreases by 3% or more. However, in Greece and Cyprus there were very low rates of nonperforming loans, of about 45% and 28%, respectively.

- From our point of view, we believe there is no need to give up firm regulation and supervision of the financial system. “Parallel markets” must be regulated, and financial technologies such as fintech are important, but we must not see them as a miracle cure. It is necessary to change the institutional culture of the global financial industry.

- At the international level, new financial products are emerging that are based on the concept of “green transition” and “green financing”, in accordance with sustainable development.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical-Methodological Aspects

- sustainable development for all of us, as a requirement of reducing economic and social inequalities and of inter and intra-country convergence;

- the principle of prevention, as a factor in saving resources and increasing economic efficiency, including financial resources;

- the principle “the polluter pays in full the damages (negative externalities)”, generated for the third parties, on different time horizons;

- the principle of public–private partnership;

- intersectoral, interregional, and interstate cooperation;

- the principle of the “critical mass” of investment;

- the principle of subsidizing the positive externalities in the production of goods and services of public and private character;

- the principle of involving all the members of the company and of financial or other participation in the cause of sustainable development;

- decoupling economic growth from the consumption of environmental resources;

- the principle of circular economy throughout the production and consumption processes;

- the principle of “win–win” cooperation, amended with the requirement of the equivalence (equality) of efficiency for each participant in the cooperation in the sense of achieving benefits, advantages, or profits commensurate with the efforts made;

- the principle of social responsibility and business ethics.

- development of the technical infrastructure, the creation of the vector of “green” indices, and the development of the “index of green companies” in order to promote ecological investments;

- creation of the financing mechanism and a system for providing information on green technologies;

- the creation of “packages” of green financial education for the human resources involved in the green financing process;

- development of new financial products that integrate environmental factors into existing products and that take into account environmental technologies and risks in lending decisions; and

- development of new financial instruments that combine banking, insurance, and investment banking features.

6.2. Practical Applications

- “Will current policies generate a viable future or a collapse?”

- “Do new technologies have the power to influence the long-term trends of global systems, so that they grow or collapse?”

- “Is the free market capable of distributing resources to ensure a viable future?”

- “The market seems to allocate the riches of the rich and emphasize the poverty of the poor. What changes this component of the global system, without which it seems impossible to stabilize population growth?”

- “Can people in industrialized societies learn to live in harmony with nature?”

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldridge, Irene, and Steven Krawciw. 2017. Real-Time Risk: What Investors Should Know About FinTech, High-Frequency. Hoboken: Wiley Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Annicchiarico, Barbara, and Nicola Giammarioli. 2004. Fiscal Rules and Sustainability of Public Finance in an Endogenous Growth Model. ECB Working Paper No. 381. Frankfurt: European Central Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Cynthia Stokes. 2012. Big History: From the Big Bang to the Present. New York: The New Press Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriu, Mihail, and Otilia Manta. 2017. Architecture of Flows and Financial Stocks—Mechanism and Transmission Channels, Flow, Transmitters and Receivers. In Proceedings of the 2017 2nd International Conference on Modelling, Simulation and Applied Mathematics (MSAM2017). Edited by Mohammad Gholami, Ram Jiwari and Kevin Weller. Advances in Intelligent Systems Research. Paris: Atlantis Press, vol. 132, pp. 219–25. [Google Scholar]

- EIB. 2007. Climate Awareness Bonds. Available online: https://www.eib.org/en/investor_relations/cab/index.htm (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- European Commission. 2018. EC Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2020a. The Multiannual Financial Framework for the Period 2021–2027. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2020b. The European Green Deal Investment Plan and Just Transition Mechanism Explained. Brussels: European Commission, January 14. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Yan, Xue-Feng Shao, Xin Cui, Xiao-Guang Yue, Kelvin J. Bwalya, and Otilia Manta. 2019. Assessing Investor Belief: An Analysis of Trading for Sustainable Growth of Stock Markets. Sustainability 11: 5600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, Han, Sicheng Li, Lin Hu, Nelson Duarte, Otilia Manta, and Xiao-Guang Yue. 2019. Risk Factor Identification of Sustainable Guarantee Network Based on Logistic Regression Algorithm. Sustainability 11: 3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Helwege, Jean, Jing-Zhi Huang, and Yuan Wang. 2014. Liquidity effects in corporate bond spreads. Journal of Banking & Finance 45: 105–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kaprauny, Julia, and Christopher Scheinsz. 2019. (In)-Credibly Green: Which Bonds Trade at a Green Bond Premium? Working Paper. Frankfurt: Goethe Universität Frankfurt. [Google Scholar]

- Manta, Otilia. 2018. Microfinance: Concepts and Applications in Rural Environments. Saarbrücken: LAP Lambert Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Manta, Otilia P., and M. Dimitriu. 2017. Architecture of Flows and Financial Stocks (Mechanism and Transmission Channels, Flow, Transmitters and Receivers). In 2nd International Conference on Modelling, Simulation and Applied Mathematics (MSAM2017). Publicarea în Advances in Intelligent Systems Research, Volume 132, 2nd International Conference on Modelling, Simulation and Applied Mathematics (MSAM 2017). Paris: Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar]

- McWaters, R. Jesse. 2015. The Future of Financial Services: How Disruptive Innovations Are Reshaping theWay Financial Services Are Structured, Provisioned and Consumed. Geneva: World Economic Forum, p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Economy. 2020. Integrated National Plan in the Field of Energy and Climate Change 2021–2030, Bucharest, Romania. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/romania_draftnecp_en.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Ristea, Lucia, and Valeriu Franc. 2013. Methodology in Scientific Research. Bucharest: Expert Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Sanicola, Lenny. 2017. What is fintech? Huffington Post. Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/what-is-fintech_b_58a20d80e4b0cd37efcfebaa?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLnJvL3VybD9zYT10JnJjdD1qJnE9JmVzcmM9cyZzb3VyY2U9d2ViJmNkPSZ2ZWQ9MmFoVUtFd2pwNmNuX2dZX3NBaFdrc2FRS0hWZTRCSkVRRmpBQWVnUUlCaEFCJnVybD1odHRwcyUzQSUyRiUyRnd3dy5odWZmcG9zdC5jb20lMkZlbnRyeSUyRndoYXQtaXMtZmludGVjaF9iXzU4YTIwZDgwZTRiMGNkMzdlZmNmZWJhYSZ1c2c9QU92VmF3MHl3eF93YWhjcmFqVmtGWW1WanFodA&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAACeR-ndSJ08INpiQ-1oT7KfzqB8ZfmfI2sVMkL3VLfoDPV4XQlBtEUZPwcB1_Rb_iu93kWdd2O6GxK5_isipDVnbLseBmP1kLQ7pCgq08UqayM2aBoJanS1e4r8n_bGuxTN6DE4qdEybW2uL3fiiaYj5tEwO1szUR0b1i1upWxmZ (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Schoenmaker, Dirk, and Willem Schramade. 2019. Principles of Sustainable Finance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scholten, Miroslava. 2017. Mind the trend! Enforcement of EU law has been moving to ‘Brussels’. Journal of European Public Policy 24: 1348–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schueffel, Patrick. 2017. The concise Fintech Compedium, School of Management Fribourg, School of Management Fribourg (HEG-FR), HES-SO. Western Switzerland: University of Applied Sciences and Arts. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2018. The Green Bond Market: 10 Years Later and Looking Ahead (Authors: Heike Reichelt, Head of Investor Relations and New Products, World Bank, Colleen Keenan, Senior Financial Officer, Investor Relations, World Bank). Available online: http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/554231525378003380/publicationpensionfundservicegreenbonds201712-rev.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Yue, Xiao-Guang, Yong Cao, Nelson Duarte, Xue-Feng Shao, and Otilia Manta. 2019. Social and Financial Inclusion through Nonbanking Institutions: A Model for Rural Romania. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12: 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zonis, Marvin. 2000. A New Decade for Business: Twenty-Four Principles of Globalization. New York: Harry Walker Agency. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manta, O.; Gouliamos, K.; Kong, J.; Li, Z.; Ha, N.M.; Mohanty, R.P.; Yang, H.; Pu, R.; Yue, X.-G. The Architecture of Financial Networks and Models of Financial Instruments According to the “Just Transition Mechanism” at the European Level. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2020, 13, 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13100235

Manta O, Gouliamos K, Kong J, Li Z, Ha NM, Mohanty RP, Yang H, Pu R, Yue X-G. The Architecture of Financial Networks and Models of Financial Instruments According to the “Just Transition Mechanism” at the European Level. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2020; 13(10):235. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13100235

Chicago/Turabian StyleManta, Otilia, Kostas Gouliamos, Jie Kong, Zhou Li, Nguyen Minh Ha, Rajendra Prasad Mohanty, Hongmei Yang, Ruihui Pu, and Xiao-Guang Yue. 2020. "The Architecture of Financial Networks and Models of Financial Instruments According to the “Just Transition Mechanism” at the European Level" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13, no. 10: 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13100235

APA StyleManta, O., Gouliamos, K., Kong, J., Li, Z., Ha, N. M., Mohanty, R. P., Yang, H., Pu, R., & Yue, X.-G. (2020). The Architecture of Financial Networks and Models of Financial Instruments According to the “Just Transition Mechanism” at the European Level. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(10), 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13100235