1. Introduction

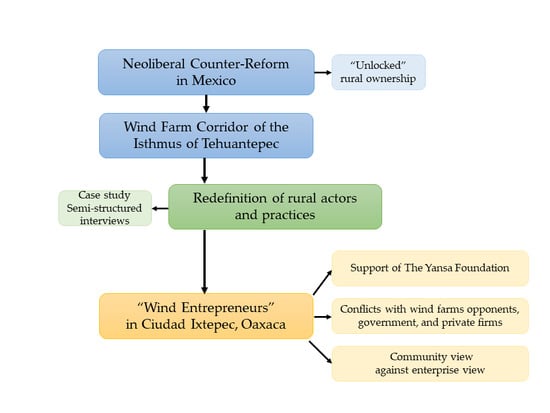

Through the perspective of new rural problems or new rurality, this paper aims to examine the redefinition of rural actors and practices in the Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec facing the Wind Farm Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec as a project oriented to boost economic development through the use of wind on a large scale. Since 1994, under the sponsorship of the Federal Electricity Commission (Comisión Federal de Electricidad, CFE), private companies have built wind farms, confronting the disapproval of residents claiming dispossession, because rural ownership is the basis for undertaking the business use of the wind.

However, in Ciudad Ixtepec, there is a different perspective on the idea of a community wind farm, which confronts the annoyance of opponents and the disbelief of the CFE and private firms. Many of the landowners have decided to become wind entrepreneurs, motivated by an inventory of natural resources that made them aware of the attractive economic benefits that wind, which is abundant in their territory, offers.

This implies a transformation of their expertise in order to get into the neoliberal counter-reform as “wind entrepreneurs”, although the original idea of a locked rural ownership in Mexico fades. That change requires openness to a global market and technological innovation as fundamental promoters to redefine rural actors and practices.

In this vein, to understand that redefinition, it is important to focus on aspects as benefits of wind farms, role of the land in the use of wind energy, requirements for the use of wind, arguments of disagreement with wind farms in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, manifestations of that disagreement, and feasibility of a community wind farm.

Hence, this paper launches a literature review to explain the context in which the case study is generated, consisting of the proposal of a wind farm managed by owners of commune land of Ciudad Ixtepec, Oaxaca. Meanwhile, the methodology emphasizes a qualitative focus supported by a case study, “worded” through semi-structured interviews. Finally, the results present the context, description, and analysis of the project of a community wind farm to expose some lights and shadows of rural transitions

2. Literature Review

The 1992 neoliberal rural reform was an amendment to constitutional and legal frameworks in order to give openness to the Mexican agro, removing rural ownership protections, and diversifying its capacities, in which the primary sector provided opportunities to the secondary and tertiary sectors of the economy. In the face of the disappearance of rural ownership protections,

Durand-Alcántara (

2009) states that “the chains were broken which once situated

ejidos and

comunidades (options of rural co-ownership in Mexico) as not attachable, inalienable, nor subject to statutory limitation, nor subject to sale or lease—by now allowing their free circulation in the capitalist market.”

The above follows the economic policy approach called the Washington Consensus, focused on counteracting the impact of the “Lost Decade” of the 1980s and restoring high growth rates (during the 1960s and 1970s). Thus, state participation in strategic sectors was replaced by the law of supply and demand, emphasizing financial liberalization, open trade, foreign direct investment and privatization.

“The Lost Decade” is the term given to Latin America’s economy in the 1980s. On this subject,

Moreno-Brid and Ros-Bosch (

2010) indicate that

During the period 1982–88 Mexico experienced a negative GDP (Gross Domestic Product) rate, and the GDP growth per capita fell more than 15%. The average annual inflation was almost 90%. In the period 1983–88, the total wage income decreased by an average of 8.1% per year. With acute contractions (24.6% in 1983 and 10.7% in 1986) in the two years of greater economic crisis. Government spending on education and health fell 30.2% and 23.9%, respectively, due to declining in real wages and decreasing of government spending and public investment in social sectors.

The Mexican economy suffered two major external shocks with negative consequences in the economy as a whole, a downfall in economic activity, hyperinflation, and many complications in the exchange and financial markets—in sum, stagnation. The first major shock was the international debt crisis, when service on foreign debt increased, thus hindering access to credit in the global capital markets.

Oks and Van Wijnbergen (

1993) mention that

The implementation of monetary policies by the United States and the United Kingdom in 1979 suddenly changed the international environment to the detriment of Mexico. Real interest rates became abruptly positive, while after the 1979 euphoria, oil prices fell almost as quickly as they had previously risen.

The second shock was the worldwide drop of oil prices in 1986 (a loss of foreign exchange income of almost $8.5 billion USD for Mexico), as well as capital flight. The combination of these circumstances resulted in the high-level debt crisis of early 1982, which was comparable at the time with the recession of the twenties and early thirties.

It is important to mention the role of international financial institutions in securing the repayment commitments of the Latin American countries’ debt crisis of 1982, which were crucial in executing Mexico’s adjustment program. Accordingly, two restructuring plans to solve the debt problem should be mentioned—the Baker Plan and the Brady Plan.

According to

Oks and Van Wijnbergen (

1993),

The Baker Plan required that the restructuring of debts with commercial banks (including new loans) be associated with structural reform programs with the seal of approval of international financial institutions (often in connection with structural adjustment loans of these institutions). Although fiscal adjustment in Mexico had begun in 1982, forced by the debt crisis, trade reform began in 1985–86; originated by the failure of previous policies, though it coincided with the increased influence of international financial institutions with the Baker Plan. Although the structural reform was accelerated, the new amounts provided by commercial banks were not enough to restore confidence or boost growth.

Given that it did not have adequate funding, the Baker Plan failed because Mexico and other Latin American countries lacked enough funds from either private banks or the World Bank to carry out the structural reform program. As a result of this failure, in 1982, Mexico suspended debt servicing commitments, thus causing the end of the Baker Plan.

During the stagnation that occurred in 1982, Mexico reached a level of deficit never seen before. Realizing that the situation could lead to the social destabilization of the area, the United States developed another plan, the Brady Plan, whose goal was to grow up in order to pay the interest burden on loans, although a reduction of debt was necessary. This would allow the debtor country a faster recovery; its effect would be a greater payment capacity of the country.

Olave (

1989) highlights Brady Plan’s most important points:

It increased the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank’s financial contribution, either with new loans or through guarantees of the payment of interest on exit bonds;

It encouraged commercial banks to work with debtor nations to achieve debt reduction and service;

It proposed changes in the rules of regulation, accounting, and tax regulations of the institutions in order to eliminate any obstacles to possible negotiations;

It gave preference to swaps (debt-for-investment swaps) as a debt-reduction mechanism;

It reinforced the idea of negotiations on a case-by-case basis, as well as the need to continue with existing stability programs.

This is how, by the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s the Mexican economic policy changed to a “Three-D” policy, the following aspects of which are mentioned by

Villarreal (

2005):

Deprotection through commercial, finance, and foreign investment liberalization;

Deregulation through liberalization of domestic markets;

Denationalization through privatization of public companies.

The most important phase of trade and financial liberalization was the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). There were many international events that favored the negotiation of this agreement and its entry into force in January 1994. One of these was precisely the political and economic transformation favored by Mikhail Gorbachev in what would soon be the former Soviet Union. Another timely event was the Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan duo, who promoted a policy of privatization and economic liberalization. Of course, the fall of the Berlin Wall must also be considered.

In recognition of these changes, the administration of Carlos Salinas De Gortari deepened not only the commercial opening, but also the financial liberalization and the privatization of several state-owned enterprises.

With NAFTA, Mexico continued its process of trade liberalization and its modernization through treaties signed with other countries, as well as its adhesion to various organizations. During the Salinas administration, Mexico signed agreements with Costa Rica, Colombia, Venezuela, and Bolivia and joined the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the World Trade Organization.

Moreno-Brid and Ros-Bosch (

2010) point out that the Mexican government had three objectives when promoting NAFTA:

Firstly, it conceived the agreement as an element of great and exclusive potential to boost Mexico’s trade with the United States and Canada, as well as the flow of foreign direct investment. Secondly, it was believed it would introduce foreign domestic companies (inside and outside the NAFTA region) to invest in the production of commercial goods in Mexico to exploit its benefits as a platform for export to the United States. Finally, the agreement also had the economic and the underscored political objective of preventing future Mexican governments from reversing the process of the economic reforms.

The policy of financial liberalization adopted by Salinas reflects the orthodox macroeconomic theory in the beginning of the 1990s also had its effects in other fields. For example, one point within the Washington Consensus was that Mexico would need financial liberalization if the country really wanted to be competitive. Mexican financial authorities were convinced that one of the problems that prevented the country from growing satisfactorily was the lack of consolidation of a financial system capable of generating enough resources for its development.

Under this idea, it was important to make the necessary adjustments to attract foreign direct investment as an important tool for the economic growth of an emerging country. In this regard, Joseph

Stiglitz (

2000) noted that

Foreign investment is not one of the three pillars of the Washington Consensus, but it is a key part of the new globalization. According to the Washington Consensus, growth takes place through liberalization, “unlocking” markets. It is assumed that privatization, liberalization and macro-stability generate a climate that attracts investment, including foreign investment. This investment produces growth. Foreign firms provide expertise and access to foreign markets, opening new possibilities for employment. These companies also have access to sources of financing, especially important in underdeveloped countries with weak local financial institutions.

The financial liberalization strategy attempted to eliminate all legal barriers to the country’s ability to receive capital from abroad. To do this, it was necessary to modify the Foreign Investment Law enacted in 1973, which restricted foreigners to a maximum participation of 49% of foreign companies in the country.

According to

Guillén-Romo (

1997), “Mexican neoliberals, such as Pedro Aspe, thought that this law contained very ambiguous definitions regarding to which sectors would actually be subject to these limits, which allowed the discretionary application of prescriptions.”

The Mexican financial system was extremely protected, with restrictions and controlled interest rates; the financial market could not respond to the demand of the international economy. Therefore, it was necessary and unpostponable to modify some laws to establish the proper panorama for a developed stock market and, at the same time, amend the imbalances of public finances. In line with Álvarez and Azpeitia (see

Álvarez-Texocotitla and Azpeitia-Sánchez 2005), the Salinas administration had two basic objectives that the financial system had to fulfill:

To increase and channel national savings effectively to more dynamic productive activities;

To expand, diversify, and modernize the system to boost productivity and competitiveness of the Mexican economy.

A basic orthodox model is also incorporated where interest rates, international reserve, and a free market play a crucial role in the modern macro dynamics. Thus, in order for the market to operate in an effective way, independently from what was stipulated in a new foreign investment legislation (1993), the Salinas administration undertook the following measures:

Liberalization of bank interest rates;

Elimination of compulsory channeling of credit resources;

Substitution and subsequent elimination of the legal reserve and the liquidity ratio.

Owing to this liberalization, of the 1155 entities that made up the State Owned Enterprises sector at the end of 1982, there were only 941 in December 1985, falling to 200 in the following 12 months (

Figure 1); since mostly all those with minority shares from the state were sold (see

Moreno-Brid 1999).

In this context,

Hoffman (

2012) noted that

Neoliberal policies (such as NAFTA in 1994) and liberalization of markets introduced since the 1980s have changed Mexico’s agricultural sector radically and have made small-scale farmers, like those in Ixtepec, increasingly vulnerable to decreasing global market prices for food crops. […] The decreasing importance of agriculture as form of livelihood for people in Ixtepec has thus also caused a weakened role of the communal governance bodies such as Ixtepec’s Commune.

Hence, private capital became available through projects of intervention in social ownership, a fact that revealed the need for a transition in knowledge in order to adapt to neoliberal rural reform, which modified the original idea of rural ownership in Mexico. It requires considering openness to global markets and technological innovation as the crucial drivers of the redefinition of rural actors and practices.

In this regard,

Keilbach (

2008) argues that “the new rurality that has crystallized in Mexico has been described and analyzed widely in terms of the emergence of new actors, new activities, and economic opportunities, in terms of resistance and conformation of new identities.”

Social phenomena are conceived from a global and local focus because openness to the world guarantees a critical and purposeful framework with contributions from diversity. In addition, the environmental resources adjacent to rural ownership are the subject of renewed management, dispute, and conflict, whose impact is also global and of interest to the public, private, and social sectors. Rural actors must consider this background while they meditate, decide, and operate their practices.

In this same way,

Sánchez-Albarrán (

2011) offers the following aspects; the new rural problem involves considering three contexts that have undergone enormous changes and in which rural society is reproduced:

The economic context, which prioritizes the effects of capital investment on land based on the application of new technologies;

The sociopolitical context allows the establishment of a legal framework to exercise civil rights, as new political actor, but also as new economic agent, as land and capital holder; and

The sociocultural context involves the gradual, but firm transformation, of their culture, customs, and ideology promoting the emergence of new rural identities.

The free circulation of rural ownership in the capitalist market has generated, and continues to generate, reaction both in favor and against, though it is possible to consider an intermediate opinion that accepts the redefinition of rural actors and practices by light of alternatives that do not involve a total adhesion to the neoliberal framework; that is to say, an adjustment from an ownership essence.

Under this modality, rural actors have the power to make decisions regarding the fate of rural ownership, and so it is crucial to include opportune advisory, technological innovation, and collective self-esteem for an optimum use of their resources in order to motivate a change of vision and action that concerns rural areas. It should be noted, however, that the rural/urban contrast has vanished due to the presence of neoliberal rural reform, which demands, in a strong way, that rural transitions be analyzed from the perspective of complexity.

3. Materials and Methods

The redefinition of rural actors and practices reveals, according to

Osorio (

2012), that “the complexity of social reality implies understanding that there is an overlap between the deep and the surface that triggers movements and processes that go in both directions.”

Hence, case study methodology from a qualitative perspective is adopted, and “worded” data was collected through semi-structured interviews because the main aspiration revolves around examining the redefinition of rural actors and practices in the Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec. This approach considers the decided intention to become wind entrepreneurs.

Of course, this circumstance links these social actors with all others involved in the Mexican electricity sector, generating interactions of interest for research that gives preeminence to the perspective from the actor.

Thus,

Long (

2007) states that an actor-oriented approach “holds that all forms of external intervention are necessarily introduced into the livelihoods of affected individuals and social groups, and as a result are mediated and transformed by those actors and their structures.”

Accordingly, semi-structured interviews were conducted with a diverse group of actors who supported or opposed the implementation of wind energy technology in the area to gain insight from their various positions (

Table 1).

Planned themes and key aspects obtained from interviews are summarized in

Table 2.

Those themes are distinguished in the case study, consisting of the project of a community wind farm in the municipality of Ciudad Ixtepec, Oaxaca. This alternative is related to the fact that the mentioned municipality is part of the Wind Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, an initiative of the Government of the state of Oaxaca aimed at managing economic development based on the use of wind on a large scale. Together with the wind farms of the CFE and private companies, the owners of commune land of Ciudad Ixtepec are attempting to become “wind entrepreneurs.” For this, they have faced several obstacles, mainly economic and political obstacles.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that all those interactions involve power relations as a feature of rural transitions.

4. Background and Context

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec region is considered a strategic site for Mexico’s energy and economic development through using wind energy to produce electricity because, pursuant to

Winrock International et al. (

2003),

Winds are extremely unidirectional, blowing mainly from North to Northeast. In addition, the land is relatively flat. For wind projects in this region, the minimum field requirement will be approximately 7.7 Ha/MW (hectares per megawatt), optimal conditions for a robust generation of wind energy. However, in some cases where there are hills, this figure may be closer to 15 Ha/MW.

Given these conditions, the capacities of electric power generation through the force of the wind oscillate between 6250 megawatts and 8800 megawatts (see

Henestroza-Orozco 2009). For this reason, the federal government and Oaxaca’s state government have taken on the management of the economic development of the Isthmus region, based on the large-scale wind sector.

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec Wind Corridor is an initiative of the State of Oaxaca, in accordance with national energy policies, oriented to promote economic development based on the use of wind. This project started in 1986, when the Federal Electricity Commission (Comisión Federal de Electricidad, CFE) installed wind power stations in the region, which drew attention to the possibilities of taking advantage of existing wind resources. Consequently, the CFE launched two wind farms, known as La Venta I, in 1994, and La Venta II, in 2006. Since 2008, several private developers have been working on placing wind farms in the region, mostly under the guise of self-sufficiency, as a response to calls from the CFE (

Table 3).

Private wind companies participate in biddings in order to obtain permits for the construction of wind farms, whose purpose is to generate electricity for self-supply or as independent producers. These procedures followed the abrogated Law of Public Electric Power Service (Ley del Servicio Público de Energía Eléctrica, LSPES) (

Ley del Servicio Público de Energía Eléctrica 1975), as well as signed contracts of interconnection with the CFE, which committed them to direct all the electric energy produced to the National Electrical System. This public entity distributes the energy as it deems necessary.

Self-supply consists of the generation of electric energy by either individuals or enterprises and is aimed at the satisfaction of their own needs, provided that this is not deleterious for the country in the judgment of the Ministry of Energy, according to Article 36, Section I, of the LSPES. It is important to point out that some of these wind parks operate as independent energy producers, accordingly to what is stipulated in Article 36, Section III, of the LSPES.

The LSPES was repealed by the Law of Electrical Industry (Ley de la Industria Eléctrica, LIE) (

Ley de la Industria Eléctrica 2014). However, the last paragraph of its second transitory article indicates that

Permissions and contracts for self-supply, cogeneration, independent production, small production, import, export and continuous self-uses granted or processed under the Public Electrical Energy Service Law will continue to be governed by the terms established in that law and other prescriptions emanated from it, while not opposed to the Law of Electrical Industry and its transitory articles.

Thereby, private wind companies share with the federal government the role of taking advantage of wind energy through the construction and management of wind farms. They mainly do so out of the requirements for capital and for knowledge and experience in the area of electric power generation by wind.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Wind Farms in the Oaxacan Isthmus: Agreement and Disagreement

In order to have the needed area to build wind farms, private wind companies enter into lease and easement agreements with landowners selected for their wind capabilities. The lease occurs from the moment in which two contracting parties mutually oblige to each other, first, to grant the temporary use of one thing, and second, to pay for that use at a previously established price. In the case of an easement, it is a nonpossessory right to use and/or enter onto the real property of another without possessing it. An example would be the permission to enter authorized by the landowner located in an area that is necessary to cross in order to access the land in which a wind farm is built, which can manifest itself through the construction of a road.

In the case of lands that belong to an

ejido or

comunidad, these contracts would be regulated by the Rural Law (Ley Agraria, LA) (

Ley Agraria 1992). In compliance with what is established in Articles 117 to 120 of the LIE, the principles of sustainability and human rights of the communities and peoples of the regions in which the electric infrastructure projects are implemented must be considered. This is done by conducting information and consultation activities directed at the communities and submitting a social impact assessment to the Ministry of Energy.

For this, private wind companies argue the benefits of placing wind technology, in the sense that they favor the conservation of the planet and the socioeconomic development of the region, and are conducted respecting the social structure of the sites in which they take part. However, they emphasize that the direct benefits to the population will be over the long term.

Against this picture, the reactions of the Isthmus population have turned primarily in an oppositional direction. This is supported by the debate of the distribution of benefits of electric energy production in the region. Thus, there has been talk of improvements in the infrastructure of the region and fairer payments for land leasing on which wind farms are built, as manifestations of reciprocity given the interference in the region.

The opposition in the Oaxacan Isthmus, especially in places like Juchitán, La Venta, or San Dionisio del Mar, has led some private companies to transfer their permits to others. This transfer disrupts the proper execution of the construction or operation of wind farms, which, from a business perspective, constitutes losses that must be addressed immediately, either through negotiations with opponents or by deciding to leave the region.

The insertion of wind technology in the Oaxacan Isthmus has confronted the following reactions:

Granting permits to the CFE for the use of commune lands;

Entering contracts of leasing commune land with private wind farms enterprises;

Promoting civil and rural lawsuits, calling for the nullification of lease contracts;

Establishment of a judicial procedure aimed at protecting human rights, claiming the illegal occupation of communal lands by the CFE for the establishment of wind parks and substations, as auxiliaries for the transmission of electricity produced;

Blockading access to wind farms under construction;

Public protests (marches, sit-ins, blockades);

Activism from a human rights perspective;

Spreading awareness of the phenomenon through forums, conferences, articles, videos, and websites, among others;

Requests for support by private wind farms enterprises, comparable to those carried out by government agencies of social development;

Partnership with non-governmental organizations to promote community-based wind projects;

Negotiations with government bodies to be part of the dynamics of wind energy utilization.

The last two responses underly the difference in the Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec. Although the granting of permits and the human rights judicial procedures are also part of this difference, this paper focuses on the partnership with non-governmental organizations to promote community-based wind projects.

5.2. Wind Entrepreneurs in Ciudad Ixtepec

In Ciudad Ixtepec, many landowners have decided to become wind entrepreneur, because “wind is part of our inventory, we are the owners” (Daniel González, Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec), by which they became aware that the wind, which is abundant in their territory, generates attractive economic benefits.

This implies a transition in knowledge for adapting to the neoliberal rural reform in order to build wind farms. This transition includes an alternative adaptation to the neoliberal model by the Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec, that is, the set of landowners under to the commune regime within that municipality. The commune regime is stipulated in article 98 of the LA under the following terms—the recognition as commune of rural cores is generated by the following processes:

A rural action of restitution for the communes stripped of their ownership;

An act of non-adversarial jurisdiction promoted by those who keep the commune status when there is no litigation in matters of possession and commune ownership;

The resolution of a lawsuit promoted by those who preserve the commune status when there is litigation or opposition of interested party regarding it; or

The process of converting from ejido to comunidad.

From these processes derive the corresponding registration in the Public Registry of Property and National Registry of Rural Land.

The Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec was recognized and titled in an area of 29,440 hectares by a presidential resolution on 17 May 1944, published in the DOF on 6 February 1945, and executed on 12 July 1945. This community is derived from the materialization of the assumption based on Section I of Article 98 of the LA, which has been presented above. On the other hand, Section II of Article 99 of the LA stipulates the existence of a Commission of Commune Ownership as a representative and administrative management organ for of the assembly of landowners, on the terms established by the commune statute and by custom. It is precisely within the Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec where this alternative option of private initiative of construction and administration of wind farms is being developed, as well as multiple expressions against it.

The area that includes the municipality of Ciudad Ixtepec is approximately 95% comunidad-owned land. Due to this, any initiative that involves the use of these areas must be approved by the majority of the landowners. For this reason, wind farm construction projections have been the subject of debates and decisions from the assembly. The landowners manifest their firm power to manage a community wind project so that they can become wind entrepreneurs, favoring economic development for landowners in the medium term and for the municipality in the long term.

The CFE built a substation in that municipality, called Ixtepec Potencia, through which wind farms are operating the interconnection to the National Electrical System. Likewise, it contracts a total of 500 megawatts of wind power. By 2012, 200 megawatts had already been awarded.

Since 2008, landowners from Ciudad Ixtepec have been planning the construction of a community wind farm with the support of the Yansa Foundation. The goal was that, through this project, they would be awarded production of at least 100 megawatts of electrical energy. That is why no wind farm is managed by a private company in this municipality, and the landowners continue negotiations with Eoliatec del Istmo, reviewing the conditions for leases and easements in order to correct mistakes and make amendments.

Together with the Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec, the Yansa Foundation is another main social actor in this alternative proposal of wind management. The Yansa Foundation is a non-governmental organization whose objective is to democratize the control of local resources and the creation of sustainable energy, food, and water systems through projects created with the collaboration of rural communities.

The Yansa Foundation is part of the Yansa Group, along with the Yansa Community Interest Company (CIC), which produces wind turbines with its own technology, and the Yansa Low-Profit Limited Liability Company (Yansa L3C), which is an investment fund that finances CIC and Yansa Foundation projects. The Yansa Foundation itself promotes wind projects in partnership with communities.

The Yansa Foundation likewise opposes the appropriation of space and management of energy resources driven by government and business institutions because these respond to a logic of capital, aimed purely at economic objectives. These institutions underrate a fundamental element in the intervened area, the population, which they consider the legitimate owner of the territory, as well as the resources that are inherent to it, including the wind.

5.3. The Model of a Community Wind Farm

The Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec has requested advice and financial support from the Yansa Foundation to develop their idea of a community wind farm. This intention to associate grew from the research carried out by Ixtepec landowners about financing options for their own wind farm; from which came the contact and later the link to a sort of business partnership. So, “wind energy can be good, it can be communal, it can be the community who decides what is needed, where it is needed, what it is needed for, and it should be the community who receives the projects’ benefits” (Sergio Oceransky, The Yansa Foundation). Thereby, Yansa L3C means to supply the capital and the Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec means to contribute the land used and its wind resources. The dividends obtained after the payment of capital costs would be divided in half between

Sustainable community development projects of social interest in Ciudad Ixtepec;

The promotion and financing of community renewable energy projects in other communities, following the same model.

The project’s budget would be made in such form that the income from the electricity produced will be sufficient to

According to the Yansa Group (

Yansa, Inc. 2020), “community involvement in Yansa projects is absolutely essential, and ensures their fundamental economic, cultural, environmental, and political rights. Collective community participation is manifested in the design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of all projects.”

Therefore, in a community wind project,

The ownership of the project belongs to the local community;

The local community plays a leading role in its planning and operation;

They assume a much greater contribution to the local economy;

The participation of the local population brings a deeper knowledge of land uses and contributes to better decisions;

The local community maintains control of the territory.

Accordingly,

Hoffman (

2012) emphasized the following three dimensions of the entrepreneurship of Ciudad Ixtepec:

An organizational, a personal and a collectivistic dimension, that all complement each other. Hence, the local indigenous collective governance body’s (Commune) ownership and control over communal territories could be secured, accountability to external shareholders avoided, and full amount of generated revenues be used for the local community’s development and further advocacy and promotion of community wind models.

The above is in opposition to private wind farm schemes, which give greater benefits to those who have one or several wind turbines on their land and much less profit to those who grant them control of their territory but who do not have a wind turbine installed in them. That model is considered individualistic and is generating conflicts in the region. Thus, a community alternative to the private business approach is one that compensates the landowners where wind turbines are installed with equivalent land in another part of the community. This option avoids conflicts in the distribution of wind turbines and contributes to a fairer and more community distribution of the benefits.

5.4. Project Preparation

Within preparations by the Commission of Commune Ownership of Ciudad Ixtepec and the Yansa Foundation to participate in biddings from CFE, a modular program of information, training, and planning was created. Each training module was tied to an element of project management—for example, environmental management, public works, business plan and management, maintenance, etc. The community is expected to participate in an effective and informed manner in the planning and execution of the project. The intention is still to begin with the first module as soon as the project’s implementation is assured.

As can be seen, this is another way of negotiating sovereignty through community participation, but confronting the conventional framework requires economic support, which in this case comes from a non-governmental organization, which is one of the emerging social actors that questions the state’s effectiveness. The Yansa Foundation’s participation has been lobbying federal government, which has not yielded the expected fruits of openness by gaining access to biddings for wind farms. Despite this, that organization continues to insist on the formation of community enterprises, not only in the Oaxacan Isthmus, since its activity has already spread to other states, such as Baja California. This makes the Yansa Foundation a mediating institution, though one of the strongest criticisms it has received is in relation to its lack of experience, since Ciudad Ixtepec constitutes the first attempt to materialize the community business dynamics.

On the other hand, the Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec granted CFE permission to build the Ixtepec Potencia substation in its lands, in exchange for allowing them to participate in biddings related to the use of wind energy. According to the landowners, although a representative of the CFE points out that “the deal with the landowners of Ciudad Ixtepec was that they gave us the space for the substation and we gave them two job placements in it, which brought us complications with the labor union” (Valentín Vences, CFE).

5.5. Community View Against Enterprise View

The discrepancy in the narratives of the social actors involved accounts for the diversity of representations, aspirations, actions, and reactions as elements which mark the tension between them.

In any case, the Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec marks the difference in the responses to the launching of wind technology in the Oaxacan Isthmus, since it has used negotiations to take part under a business logic, a dynamic that has been criticized by radical opponents, because

It is not true that government and companies say that we are business partners, no, they do not want independent projects or community projects … Our struggle is against the wind project, because it is a project that has been imposed, that is not ours, that comes from outside, that does not respect us, that competes with our life. The experience of Ciudad Ixtepec is respectable, however, we say no to the wind project.

(Bettina Cruz, activist from Juchitán, Oaxaca)

In addition, the Front of Mexican Energy Workers (

Frente de Trabajadores de la Energía de México 2012) noted that “the Yansa group and ‘environmentalists’ who represent them mislead the communities. What they are proposing is a private business, attracting landowners as partners. ‘Convinced’ or deceived, they are deluded into putting their territory as capital and believing that they can market wind in exchange for money.”

In the same way that private wind farms have been looked upon with suspicion, so too has this initiative to take advantage of the wind under a community form. The argument is that they do not have the capital, knowledge, and experience for the great task of producing electricity through wind, “since we need qualified and specialized, not makeshift, companies that know only a little about how to operate a park or build a park, neither of these two is simple” (Itzia Andrade, Acciona Energía).

Nonetheless, the confidence of the owners of commune land of Ciudad Ixtepec resonates in statements such as the following: “Each enterprise has the risk of failure. Our risk would be minimal, perhaps a part of land that could never be used for anything else” (Daniel González, Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec).

The proposal of the landowners from Ixtepec to join as wind entrepreneurs has still not been satisfactorily addressed. Despite the power with which they count, as shown in negotiations with CFE and the support of the Yansa Foundation, it has been because of capital conditions that they have not been allowed to participate in any bidding. In this way, the Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec still faces obstacles to become a participant in the wholesale electricity market.

In this regard,

Boyer (

2019) observed that

Ixtepec shows us the oscillating life-and-death drives of aeolian political imagination: images of revolutionary breakthroughs and alternative futures coexisting with repetitions of habit and tradition. It gives us a glimpse of the turbulence that gathers along the edges of flows of enabling pouvoir as they swirl around sites of rapid energy development. And because it is still not clear whether Yansa-Ixtepec will never be or whether it is simply not yet, it even captures something of the paradoxical quality of life and the experience of time in the Anthropocene.

As can be seen, there is a duality to the owners of commune land of Ciudad Ixtepec—they can be affected by wind technology, but they are able to allow or disclaim the use of their land to the CFE and private companies and, likewise, the planning a wind farm. In this way, they support the idea of managing resources to obtain economic benefits, facing opposition and mistrust regarding their capacities, which constitutes a common scheme of the redefinition of rural actors and practices.

6. Conclusions

The Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec continues to promote the project of a community wind farm under the premise that its members want to be wind entrepreneurs because they are aware that the use of this resource, which is abundant in their territory, generates economic benefits. It should be emphasized that the development of an inventory of natural resources is the starting point of the Ixtepec initiative.

Therefore, it is possible to affirm the redefinition of rural actors and practices. In this redefinition, traditional aspects are conserved in terms of territory perception and the internal management of the community, the latter appropriate to the stipulations of the LA to secure the formality that this law establishes, with a view to be linked with the actors immersed in the wholesale electricity market, for which they already promote strategic alliances. Of course, its object of work has been modified, since it will be the production of electrical energy from wind turbines; in other words, using technological innovation.

If this initiative has not yet materialized, it is due to the Commune of Ciudad Ixtepec being an atypical social actor in the neoliberal context for the exploitation of natural resources, at least in Mexico. However, the new rural problem predicts these ups and downs, so strategies such as expert advice are visualized to refine the arguments and mechanisms of intervention, basing them on theory, legislation, institutions, and the discourse of inclusion as it is evoked in international society.

At this point, it is possible to note that

Owners of commune land of Ciudad Ixtepec are attempting to become wind entrepreneurs;

This scope arises by an inventory of natural resources, showing wind economic benefits;

This decision conflicts with wind farms opponents, government, and private firms;

The base is the neoliberal counter reform, oriented to remove legal protections to rural ownership;

It is possible to affirm a redefinition of rural actors and practices in a neoliberal framework, even though this new approach could appear incongruous to commune uses.

In this context, different interests generate diverse management strategies, including the proposal of a wind farm lead by owners of commune land of Ciudad Ixtepec, who were not considered in the business models of the government and private wind companies, in view of which they argue that they can also become “wind entrepreneurs”.