The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Poorer: Social Media and the Post-IPO Behavior of Investors in Biotechnology Firms: The Relationship with Twitter Volume

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. IPOs and Long-Term Stock Performance

2.2. Media and (Post-IPO) Stock Performance

This leads to a positive feedback effect, in which big returns are followed by more big returns as a result of increased media coverage. By contrast, Fang and Peress (2009), found that a portfolio of stocks not covered by the media outperformed a portfolio of stocks with high media coverage by 3% per year following the portfolio’s formation. In their view, the “no media premium” may stem from limitations on trading or may serve as compensation for little or lack of information. Bhattacharya et al. (2009) explored the role of the media in the internet IPO bubble between 1996 and 2000, finding that media coverage was much more intense for internet IPOs. There were more total news items, both positive and negative, for internet IPOs than for a matching sample of non-internet IPOs. The effect on daily abnormal returns, which was lower for internet IPOs, especially during the bubble period, indicates that the market largely discounted the media hype. Siev (2014) documented that firms publishing a low number of press releases (PRs) enjoy higher returns than those publishing a high number of PRs. Firms that enjoy a high level of public attention due to a much higher volume of annual PRs get noticed more, which leads to overpricing, which can ultimately yield lower returns.“The role of the news media in the stock market is not, as commonly believed, simply as a convenient tool for investors who are reacting directly to the economically significant news itself. The media actively shape public attention and categories of thought, and they create the environment within which the stock market events we see are played out”.

3. Stock Behavior Post-IPO

3.1. Research Goals and Hypotheses

3.2. Data and Method

3.3. Results

4. Tweets and IPO Returns

4.1. Research Goals and Hypotheses

4.2. Data and Method

4.3. Results

4.3.1. Univariate Analysis

4.3.2. Multivariate Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Market Value Above | USD 100 Million | USD 200 Million | USD 300 Million | USD 400 Million | USD 500 Million | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days Relative to Event | CAAR | t-Stat. | CAAR | t-Stat. | CAAR | t-Stat. | CAAR | t-Stat. | CAAR | t-Stat. |

| 1 to 10 | 1.70% | 0.31 | 3.15% | 0.58 | 3.10% | 0.56 | 2.59% | 0.47 | 2.54% | 0.46 |

| 1 to 20 | 4.25% | 0.88 | 6.16% | 1.37 | 5.76% | 1.28 | 5.50% | 1.18 | 5.69% | 1.21 |

| 1 to 50 | 3.08% | 0.62 | 6.01% | 1.22 | 9.99% | 2.07 | 9.48% | 1.94 | 9.60% | 1.88 |

| 1 to 100 | 1.16% | 0.25 | 4.87% | 1.10 | 10.23% | 2.32 | 9.38% | 2.11 | 13.78% | 3.25 |

| 1 to 150 | −5.75% | −1.30 | −1.49% | −0.35 | 5.42% | 1.27 | 4.27% | 0.99 | 10.20% | 2.47 |

| 1 to 200 | −9.59% | −2.08 | −3.24% | −0.73 | 5.33% | 1.24 | 5.29% | 1.21 | 13.88% | 3.55 |

| 1 to 250 | −15.43% | −3.31 | −7.14% | −1.67 | 0.44% | 0.10 | −1.61% | −0.37 | 7.81% | 2.03 |

| 1 to 375 | −27.48% | −5.85 | −15.69% | −3.49 | −3.00% | −0.67 | −3.03% | −0.66 | 6.26% | 1.54 |

| 1 to 550 | −48.65% | −9.76 | −38.58% | −7.71 | −19.47% | −3.99 | −11.8% | −2.83 | −5.62% | −1.51 |

| 1 to 755 | −77.80% | −17.7 | −68.63% | −14.9 | −46.55% | −13.20 | −37.4% | −11.7 | −38.46% | −11.39 |

| 1 | VIX is a popular measure of the stock market’s expectation of volatility implied by S&P 500 index options. It is calculated and disseminated on a real-time basis by the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE), and is commonly referred to as the fear index or the fear gauge (Wikipedia). |

| 2 | EvaluatePharma database is one of the leading global pharma databases: http://www.evaluate.com/ (accessed on 22 September 2017). |

| 3 | A detailed list of the companies can be provided upon request. |

| 4 | Market capitalization for December of the IPO year was calculated by multiplying the number of shares appearing in the firms’ profit and loss statements by the stock prices on that day. The results were confirmed with the values appearing on the stockraw.com website. |

| 5 | The companies’ market capitalization series is not normally distributed, as evidenced by Jarque-Bera Test results. |

| 6 | One of the research goals was to explore whether firms that had an active tweeting policy had an advantage over these that did not, with respect to returns. Surprisingly, firms’ activity on Twitter was non-existent or very low. For example, in the IPO year, only 15 out of 182 companies used Twitter and were responsible for less than 0.6% of the total number of tweets. This low participation rate within the total number of tweets rendered this analysis meaningless. |

| 7 | Due to the limitations of using Twitter API, I performed this analysis only for the years 2013–2017. |

| 8 | Market capitalization is calculated for December 31 of each year relative to the IPO date. |

| 9 | Despite the relative simplicity of the regression models offered, they are well specified, as was proven by heteroscedasticity tests. |

References

- Antweiler, Werner, and Murray Z. Frank. 2004. Is all that talk just noise? The information content of internet stock message boards. The Journal of Finance 59: 1259–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, Brad M., and Terrance Odean. 2007. All that glitters: The effect of attention and news on the buying behavior of individual and institutional investors. The Review of Financial Studies 21: 785–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berk, Ales S., and Polona Peterle. 2015. Initial and long-run IPO returns in Central and Eastern Europe. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 51: S42–S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, Utpal, Neal Galpin, Rina Ray, and Xiaoyun Yu. 2009. The role of the media in the internet IPO bubble. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 44: 657–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Binder, John. 1998. The event study methodology since 1969. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 11: 111–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubaker, Sabri, Alexis Cellier, Riadh Manita, and Narjess Toumi. 2020. Ownership structure and long-run performance of French IPO firms. Management International 24: 135–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Jerry, Fuwei Jiang, and Jay R. Ritter. 2015. Patents, Innovation, and Performance of Venture Capital-Backed IPOs. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2364668 (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Chen, Chao, and Haoping Xu. 2015. The Roles of Innovation Input and Outcome in IPO Pricing—Evidence from the Bio-Pharmaceutical Industry in China. Working Paper. Shanghai: Fudan University. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Hailiang, Prabuddha De, Yu Jeffrey Hu, and Byoung-Hyoun Hwang. 2014. Wisdom of crowds: The value of stock opinions transmitted through social media. The Review of Financial Studies 27: 1367–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambra, Michael, Laura Casares Field, and Matthew T. Gustafson. 2015. The JOBS Act and IPO volume: Evidence that disclosure costs affect the IPO decision. Journal of Financial Economics 116: 121–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, Sanjiv R., and Mike Y. Chen. 2007. Yahoo! for Amazon: Sentiment extraction from small talk on the web. Management Science 53: 1375–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edwards, Mark. 2021. The Indomitable Biotech IPO Window—What’s Keeping it Open? Les Nouvelles-Journal of the Licensing Executives Society 56: 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Lily, and Joel Peress. 2009. Media coverage and the cross-section of stock returns. The Journal of Finance 64: 2023–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbergskog, Jens-Otto, and Christer Ryland Blom. 2014. Twitter and Stock Returns. Master’s thesis, BI Norwegian Business School Oslo, Oslo, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Yan, Connie X. Mao, and Rui Zhong. 2006. Divergence of opinion and long-term performance of initial public offerings. Journal of Financial Research 29: 113–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Eric, and Karrie Karahalios. 2010. Widespread Worry and the Stock Market. Paper presented at Fourth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Washington, DC, USA, May 23–26; pp. 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Goergen, Marc, Arif Khurshed, and Luc Renneboog. 2009. Why are the French so different from the Germans? Underpricing of IPOs on the Euro New Markets. International Review of Law and Economics 29: 260–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gregori, Gian Luca, Luca Marinelli, Camilla Mazzoli, and Sabrina Severini. 2020. The social side of IPOs: Twitter sentiment and investors’ attention in the IPO primary market. African Journal of Business Management 14: 529–39. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Re-Jin, and Nan Zhou. 2016. Innovation capability and post-IPO performance. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 46: 335–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, Bharat A., and Omesh Kini. 1994. The post-issue operating performance of IPO firms. The Journal of Finance 49: 1699–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komenkul, Kulabutr, and Santi Kiranand. 2017. Aftermarket Performance of Health Care and Biopharmaceutical IPOs: Evidence from ASEAN Countries. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing 54: 0046958017727105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, Abhishek, and Seshadev Sahoo. 2021. Do anchor investors affect long run performance? Evidence from Indian IPO markets. Pacific Accounting Review 33: 322–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, Tammy. 2015. Twitter Volume and First Day IPO Performance. New York: The Leonard Glucksman Institute for Research in Securities Markets, Stern School of Business. [Google Scholar]

- Liew, Jim Kyung-Soo, and Garrett Zhengyuan Wang. 2016. Twitter sentiment and IPO performance: A cross-sectional examination. The Journal of Portfolio Management 42: 129–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, Tim, and Jay R. Ritter. 1995. The new issues puzzle. The Journal of Finance 50: 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, Antonio S., and John E. Parsons. 1998. Going public and the ownership structure of the firm. Journal of Financial Economics 49: 79–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, Robert C. 1987. A simple model of capital market equilibrium with incomplete information. The Journal of Finance 42: 483–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, Jay R. 2020. IPO Statistics for 2020 and Earlier Years. Available online: https://site.warrington.ufl.edu/ritter/ipo-data/ (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Ritter, Jay R., and Ivo Welch. 2002. A review of IPO activity, pricing, and allocations. The Journal of Finance 57: 1795–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shiller, Robert J. 2015. Six. The News Media. In Irrational Exuberance. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 101–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, Yoshiki, and Hideki Takei. 2016. Examining the Existence of Long-run Initial Public Offering (IPO) Underperformance at Three Different Stock Exchange Markets in Japan. Business Management and Strategy 7: 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siev, Smadar. 2014. The PR Premium. Journal of Behavioral Finance 15: 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/1764/global-pharmaceutical-industry/ (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Sul, Hongkee, Alan R. Dennis, and Lingyao Ivy Yuan. 2014. Trading on Twitter: The financial information content of emotion in social media. Paper presented at 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, January 6–9; pp. 806–15. [Google Scholar]

- Thakor, Richard T., Nicholas Anaya, Yuwei Zhang, Christian Vilanilam, Kien Wei Siah, Chi Heem Wong, and Andrew W. Lo. 2017. Just how good an investment is the biopharmaceutical sector? Nature Biotechnology 35: 1149–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wysocki, Peter D. 1998. Cheap Talk on the Web: The Determinants of Postings on Stock Message Boards; University of Michigan Business School. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.160170 (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Zhang, Xue, Hauke Fuehres, and Peter A. Gloor. 2011. Predicting stock market indicators through twitter “I hope it is not as bad as I fear”. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 26: 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zingales, Luigi. 1995. Insider ownership and the decision to go public. The Review of Economic Studies 62: 425–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Total | Biotech. | Biotech. (%) | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 248 | 52 | 17% | 30 |

| 2014 | 312 | 85 | 24% | 70 |

| 2015 | 200 | 64 | 27% | 49 |

| 2016 | 128 | 33 | 25% | 29 |

| 2017 | 210 | 51 | 24% | 50 |

| 2018 | 258 | 82 | 32% | 82 |

| 2019 | 266 | 69 | 26% | 57 |

| Total | 1622 | 403 | 367 |

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2013–2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 487 | 405 | 489 | 425 | 499 | 766 | 650 | 556 |

| Median | 374 | 229 | 287 | 299 | 368 | 337 | 301 | 297 |

| Min. | 45 | 11 | 1 | 9 | 19 | 12 | 8 | 1 |

| Max. | 2308 | 2165 | 2347 | 1843 | 2685 | 11,528 | 7166 | 11,528 |

| Std. Dev. | 456 | 452 | 576 | 444 | 521 | 1600 | 1129 | 964 |

| Count | 30 | 70 | 49 | 29 | 50 | 82 | 57 | 367 |

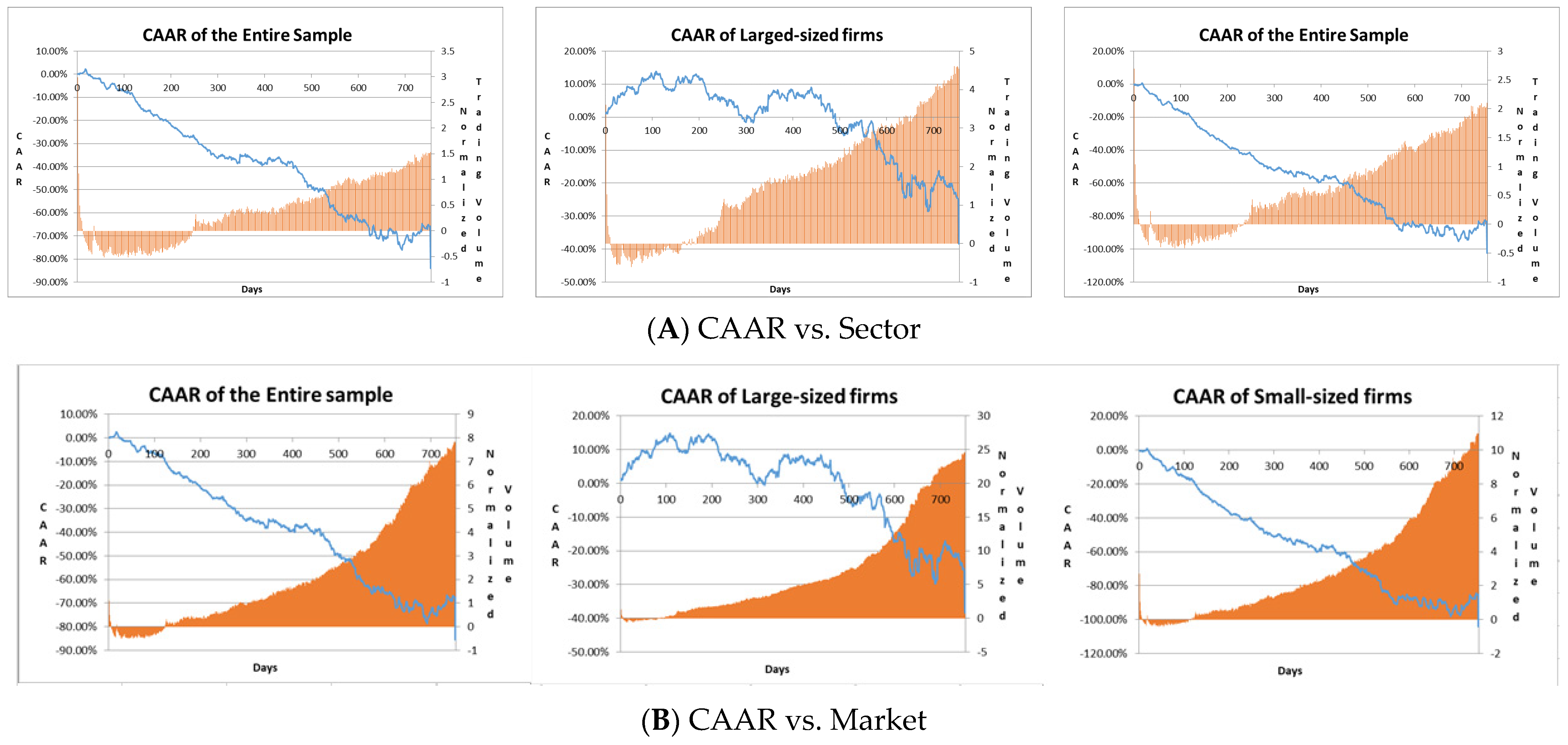

| Sector Index | Market Index | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days | All Sample | Large Firms | Small Firms | All Sample | Large Firms | Small Firms | ||||||

| CAAR | t-Stat. | CAAR | t-Stat. | CAAR | t-Stat. | CAAR | t-Stat. | CAAR | t-Stat. | CAAR | t-Stat. | |

| 1 to 10 | 0.26% | 0.05 | 2.71% | 0.50 | −0.66% | −0.12 | 0.41% | 0.07 | 2.86% | 0.52 | −0.80% | −0.14 |

| 1 to 17 | 2.35% | 0.47 | 6.13% | 1.22 | 0.60% | 0.12 | 2.58% | 0.52 | 6.20% | 1.22 | 0.91% | 0.18 |

| 1 to 50 | −2.70% | −0.52 | 9.25% | 1.81 | −8.22% | −1.65 | −2.20% | −0.43 | 9.60% | 1.88 | −8.54% | −1.71 |

| 1 to 100 | −7.10% | −1.54 | 12.91% | 3.14 | −16.51% | −3.64 | −6.31% | −1.36 | 13.78% | 3.25 | −16.38% | −3.62 |

| 1 to 150 | −16.04% | −3.55 | 9.07% | 2.26 | −26.80% | −5.99 | −15.08% | −3.29 | 10.20% | 2.47 | −27.70% | −6.28 |

| 1 to 200 | −21.46% | −4.62 | 12.47% | 3.28 | −36.35% | −7.77 | −20.53% | −4.32 | 13.88% | 3.55 | −37.06% | −8.09 |

| 1 to 250 | −26.74% | −5.71 | 6.00% | 1.58 | −40.56% | −8.46 | −25.21% | −5.33 | 7.81% | 2.03 | −41.89% | −8.84 |

| 1 to 375 | −36.80% | −8.03 | 5.96% | 1.49 | −55.31% | −12.01 | −36.72% | −7.84 | 6.26% | 1.54 | −55.30% | −12.32 |

| 1 to 550 | −58.61% | −11.92 | −4.09% | −1.11 | −83.62% | −16.24 | −60.40% | −12.07 | −5.62% | −1.51 | −81.71% | −16.23 |

| 1 to 755 | −84.08% | −19.00 | −38.45% | −11.55 | −104.17% | −22.45 | −85.40% | −19.19 | −38.46% | −11.39 | −102.3% | −22.10 |

| Obs. | 367 | 116 | 251 | 367 | 116 | 251 | ||||||

| IPO Year − 1 | IPO Year | IPO Year + 1 | IPO Year + 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 359 | 2237 | 3083 | 3558 |

| Median | 246 | 1524 | 2377 | 2326 |

| Std. Dev. | 377 | 2690 | 2978 | 3976 |

| Min. | 0 | 0 | 197 | 15 |

| Max. | 2035 | 26,126 | 20,022 | 27,579 |

| Tweet Volumes | 65,349 | 407,067 | 548,815 | 542,232 |

| Observations | 182 | 182 | 178 | 147 |

| Panel A: IPO Year | |||||

| LTV | HTV | Diff. | p-Value | ||

| Market Value (USD million) | 322.74 | 585.66 | 262.91 | 0 | |

| Return | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.08 | |

| Trading Volume | 94,321 | 267,332 | 173,011 | 0 | |

| Return’s Volatility | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.14 | |

| Beta | 0.68 | 1 | 0.31 | 0.03 | |

| Observations | 91 | 91 | |||

| Panel B: IPO Year + 1 | |||||

| LTV | HTV | Diff. | p-Value | ||

| Market Value (USD Million) | 418.17 | 844.56 | 426.38 | 0.001 | |

| Return | −0.15 | 0.36 | 0.51 | 0.001 | |

| Trading Volume | 162,046 | 441,602 | 279,556 | 0 | |

| Return’s Volatility | 0.044 | 0.057 | 0.013 | 0.001 | |

| Beta | 0.65 | 0.87 | 0.22 | 0.07 | |

| Observations | 89 | 89 | |||

| Panel C: IPO Year + 2 | |||||

| LTV | HTV | Diff. | p-Value | ||

| Market Value (USD million) | 493.44 | 841.79 | 348.35 | 0.017 | |

| Return | 0 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.043 | |

| Trading Volume | 244,890 | 660,862 | 415,973 | 0 | |

| Return’s Volatility | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0 | |

| Beta | 0.83 | 1.26 | 0.43 | 0 | |

| Observations | 75 | 72 | |||

| Panel D: Absolute Tweet Volumes per Firm Size | |||||

| Absolute Tweet Volume | Small | Large | p-Value | ||

| IPO Year − 1 | 310 | 474 | 0.01 | ||

| IPO Year | 2068 | 2636 | 0.07 | ||

| IPO Year + 1 | 3063 | 3135 | 0.43 | ||

| IPO Year + 2 | 3404 | 4001 | 0.20 | ||

| Panel A: Explaining Returns | ||||||

| IPO Year | IPO Year + 1 | IPO Year + 2 | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Intercept | 1.09 (0.07) | 1.21 (0.05) | −0.14 (0.44) | −0.21 (0.26) | −0.05 (0.80) | −0.05 (0.79) |

| Year 2013 | −1.06 (0.05) | −1.23 (0.03) | 0.00 (0.98) | 0.00 (0.99) | −0.55 (0.08) | −0.54 (0.08) |

| Year 2014 | −1.03 (0.05) | −1.23 (0.03) | −0.12 (0.61) | −0.08 (0.75) | −0.03 (0.88) | −0.04 (0.85) |

| Year 2015 | −1.45 (0.02) | −1.61 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.88) | −0.07 (0.71) | ||

| Year 2016 | −1.28 (0.02) | −1.49 (0.01) | ||||

| Rm | 1.60 (0.20) | 1.64 (0.20) | 2.13 (0.05) | 2.69 (0.02) | 1.2 (0.37) | 1.2 (0.36) |

| NMV | 0.22 (0.00) | 0.26 (0.00) | 0.03 (0.74) | |||

| HTV | 0.18 (0.21) | 0.30 (0.04) | 0.36 (0.01) | 0.47 (0.00) | 0.46 (0.01) | 0.47 (0.01) |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| F stat (p-val.) | 7.08 (0.00) | 6.18 (0.00) | 9.86 (0.00) | 7.68 (0.00) | 2.96 (0.01) | 3.69 (0.00) |

| Obs. | 182 | 182 | 178 | 178 | 147 | 147 |

| Panel B: Explaining AR to Sector | ||||||

| IPO Year | IPO Year + 1 | IPO Year + 2 | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Intercept | 0.20 (0.59) | 0.31 (0.42) | −0.13 (0.38) | −0.22 (0.16) | 0.07 (0.74) | 0.06 (0.77) |

| Year 2013 | −0.18 (0.64) | −0.32 (0.42) | −0.05 (0.80) | −0.05 (0.80) | −0.58 (0.02) | −0.58 (0.02) |

| Year 2014 | −0.08 (0.84) | −0.24 (0.53) | −0.34 (0.03) | −0.37 (0.02) | −0.02 (0.91) | −0.03 (0.87) |

| Year 2015 | −0.69 (0.07) | −0.84 (0.03) | −0.04 (0.82) | −0.16 (0.34) | ||

| Year 2016 | −0.36 (0.35) | −0.54 (0.18) | ||||

| Beta | −0.19 (0.00) | −0.19 (0.00) | −0.03 (0.78) | 0.07 (0.49) | −0.08 (0.52) | −0.08 (0.54) |

| NMV | 0.18 (0.00) | 0.25 (0.00) | 0.03 (0.69) | |||

| HTV | 0.08 (0.4) | 0.18 (0.07) | 0.19 (0.09) | 0.27 (0.03) | 0.49 (0.01) | 0.50 (0.01) |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| F stat (p-val.) | 8.43 (0.00) | 7.06 (0.00) | 6.55 (0.00) | 3.14 (0.01) | 2.25 (0.05) | 2.79 (0.03) |

| Obs. | 182 | 182 | 178 | 178 | 147 | 147 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siev, S. The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Poorer: Social Media and the Post-IPO Behavior of Investors in Biotechnology Firms: The Relationship with Twitter Volume. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2021, 14, 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14100456

Siev S. The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Poorer: Social Media and the Post-IPO Behavior of Investors in Biotechnology Firms: The Relationship with Twitter Volume. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2021; 14(10):456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14100456

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiev, Smadar. 2021. "The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Poorer: Social Media and the Post-IPO Behavior of Investors in Biotechnology Firms: The Relationship with Twitter Volume" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14, no. 10: 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14100456

APA StyleSiev, S. (2021). The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Poorer: Social Media and the Post-IPO Behavior of Investors in Biotechnology Firms: The Relationship with Twitter Volume. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(10), 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14100456