1. Introduction

Family entrepreneurship has a long tradition and is one of the most common forms of entrepreneurship in the world (

Nordqvist et al. 2013), and thus it needs to be given sufficient attention. There are family businesses in Europe that have been operating continuously for more than 100 years (

Ansari et al. 2014), and even some Asian family businesses are among the largest multinational companies (

Zhou et al. 2016). The critical point in the life cycle of every family business is the process of generational exchange, i.e., succession (

Bennedsen et al. 2015). It is a dynamic process that involves the transfer of knowledge, property and resources from one generation to another (

Cabrera-Suárez and Martín-Santana 2012). Although, “cronyism” is assessed negatively, it is a widespread practice in family businesses that can be a source of business benefits (

Steier and Miller 2010).

The generational exchange of a CEO is an important and, at the same time, challenging event for all types of companies (

Reinganum 1985). The success of succession has two dimensions: subjective satisfaction with the process of succession, and objective effectiveness of this process (

Morris et al. 1997). According to research, only 30% of family businesses survive this process in the first generational exchange (

Davis and Harveston 1998;

Mathews and Blumentritt 2015;

Lefebvre and Lefebvre 2016), and after this process, 8 to 32.5% of companies fail (

Wright et al. 1995). Smaller family businesses that have been on the market for about 30 years are often at risk of sudden owner departure. With this sudden departure, problems arise in the area of an insufficiently implemented succession process as the cause of the company’s demise (

Santarelli and Lotti 2005). Every year, about a thousand family businesses fail in the succession process (

Yedder 2018). In Japan, almost 70,000 SMEs stop operations each year, and thus succession is considered one of the biggest social problems (

Kamei and Dana 2012). The research thus far is considered an important element in this process of planning and management professionalization (

Yedder 2018). The succession process is included in the risk management of family businesses. Family members do not take risk-related measures because it is difficult for them and thus they avoid it, which is also related to the great failure of generational transfer. Risk assessment is challenging in family businesses because it lacks the ability to set priorities, procedures and controls for risk assessment (

Visser and van Scheers 2018). According to research, family businesses have a greater risk aversion than non-family businesses (

Naldi et al. 2007;

Yeh and Liao 2019).

We found several studies that claim that the succession process fails due to an unclear succession plan, incompetent and unprepared successors or family disputes (

Dyer 1986;

Morris et al. 1997). In family businesses, this process is influenced by all family members (

Sharma et al. 2001), and for this reason, the process of succession is influenced mainly by emotions (

Astrachan and Jaskiewicz 2008). A successful succession process can help a family business achieve or maintain a competitive advantage over non-family businesses (

Cabrera-Suárez et al. 2001). According to

Coffman (

2014), small family businesses need help to develop a succession plan to ensure the smooth retirement of current owners, as these businesses have a higher risk of succession failure.

Senegović et al. (

2015) considered the postponement of the decision on generational transfer to be the biggest business and managerial risk. A well-run generational change with a risk-based approach can turn a family business into a growing and dynamic business. The problem with research in family businesses is that we cannot examine the organization from an evolutionary point of view (

Aldrich 1999).

The research of this article focuses on the critical factors that influence the success of the business transfer between owner and successor. To explore these topics in depth, we opted for qualitative research (

De Massis and Kotlar 2014;

Pöschl and Freiling 2020). In our research, we focused on the period before handing over the family business to the successor. The respondents of our research were the current owners of family businesses in Slovakia, in which we dealt with the discovery of risk factors during the entire succession process (starting the succession process, successor selection, successor education, intergenerational transfer) (

Hešková and Vojtko 2008). As a method of data collection, we chose semi-structured interviews (

Santarelli and Lotti 2005;

Tirdasari and Dhewanto 2012;

Liu 2018;

Xian et al. 2021), which were performed with each owner separately, and then the answers were transcribed into written form. The entered data were evaluated by the text mining method (

Miner et al. 2012;

Jung and Lee 2020), where we determined the importance of expressions in individual phases of the succession process. Based on the results of the research of the succession process, we propose recommendations for the elimination of these risks in business practice, which can help to successfully manage the succession process not only in Slovakia but also elsewhere.

We consider the Slovak experience to be relevant from the point of view that in Slovakia, only the first generational changes are taking place in many companies because family businesses in Slovakia began to emerge after 1989, while in other parts of the world, there have been several generational changes. These results show the state of family businesses in a region where the first generational changes are taking place and can be further compared with countries where they have been dealing with this issue for several generations. The given comparison can reveal whether the risk factors in succession are the same or change with a change in culture or with the possibility of a family business in a given country.

We focused our research on family business owners. We see the potential for further research in the implementation of similar research on potential successors of family businesses. We also see the potential for further research on the former owners and successors of family businesses, where the family business has disappeared through a generational transfer.

4. Results

This research evaluates the position of the current owners of family businesses in the succession process. It focuses on the detection of risk factors that may have a negative impact on generational exchange in family businesses and thus cause the demise of the business. The owners evaluated the individual phases of the succession process in their family business from the start of the process to the generational transfer.

We found that only 48.64% of family business owners have already started the succession process. It was mainly about determining the successor of the family business, the direction of their education and their involvement in the operation of the family business. The owners placed the greatest weight on the deal (

Table 3) between them and the potential successors. The need to address succession was added to the time period the company has been on the market. For companies that have been on the market for a shorter period, these did not attach importance to this issue. Succession in our research was actively addressed mainly by companies that have been on the market for more than 15 years. The time was also associated with the age of the owner and what time they had until retirement. If the owners felt that they would be able to run a family business for at least another 10 years, they did not address the issue of succession or did not address it in detail. We found that succession is handled mainly by owners over 50 years of age. As many as 81.08% of family businesses do not have a succession plan in place. In the survey, we found that 70.27% of family businesses have no succession plan and do not plan to compile it in the future. A total of 10.81% of the respondents stated that they do not have a plan, but it is a good incentive for them, and they plan to draw one up. If we go to family businesses that have a succession plan, we see that only 18.92% of family businesses have one, of which 8.11% have one in writing and elaborated in detail, and 10.81% only have one orally. Succession plans in oral form are mostly compiled only in points, without any time specificity.

Preparing a succession plan is an activity that owners are responsible for. Owners who have a succession plan in place said that they have drawn it up in writing and have been leading the successor according to it. In most cases, the plan has been consulted with an expert and is aimed at the gradual development of the successor in the family business. The plan was described orally by the owners as an informal agreement between them and potential successors. We did not find any connection in the results with the development of the succession plan and with factors such as the age of the owner or the age of the family business. The only factor related to the development of the plan was gender. The owners who have a succession plan were men. Owners who do not have a succession plan said that they do not feel the need to draw up such a plan. They feel they have enough time to deal with this issue. They let the succession run its course and postpone the start of the process. They want to stand by their successors in taking over the business and making decisions. For them, the succession process means only a generational transfer. In the survey, we found that many family business owners had only just first heard about succession plans. In practice, this meant that they did not know that this process needed to be planned and managed. It was not just younger owners or younger businesses. The older owners also took succession for granted without taking any necessary steps. Some have been inspired and want to build it in the future, while others find it unnecessary because they only have a small family business. Although we found that most owners do not have a succession plan, the plan came out as the second most important term, especially the written plan. The basis of the written plan for them was the legal conditions of the generational exchange (division of competencies in the company and part of the company among the successors). Owners with more than one offspring focused on this legal division. They wanted to prevent disagreements between siblings from disrupting the company’s life cycle in the future. Only after this step did they consider it appropriate to address the timing of the succession process. The last two terms were “successor”, which represented that the succession does not begin until the owner has a descendant, and “time”. The time in the answers was mainly related to the age of the owner and successor. On the one hand is the owner, who can feel healthy, and on the other, the age of the successor, who may be too young for the owner to start this process. During the interviews, we found that the owners do not consider the succession process to be long.

In our research, all owners who had a designated successor had as successors a direct offspring. Owners who did not have a designated successor had no offspring yet. As many as 2/3 of the successors (59.46%) were led from childhood to take over the family business. Successors who have not been led since childhood are given the opportunity by the owners to decide in adulthood whether they want to join the family business or not. There were 27.03% of them in the survey. Successors who have not been led since childhood mainly dominated companies that have been on the market for more than 21 years, but we did not find a relationship with the age of the owner or gender. Only 13.51% of family businesses did not have a designated successor. A successor was not intended primarily for companies that have been on the market for less than 15 years and, at the same time, where the owners are less than 50 years old. Although not all successors have been led since childhood to take over the family business, all owners have agreed that they prefer their own offspring as successors, in order to keep the business in the family.

Family business owners placed the greatest emphasis on guiding their children to work in the family business (

Table 4). Almost all the owners agreed that the successors built an emotional bond with the company from childhood (also those successors who have not been led since childhood), thus connecting the family with the company. The only exception was family businesses up to 5 years of age. Their owners stated that the successors have had knowledge of the field since childhood. From the owners’ point of view, it was about influencing potential successors, especially in the choice of secondary school and subsequently also university. If we look at the owners who did not lead their descendants to take over the family business, we found that the owners tried to build an emotional bond with the successors but, at the same time, left them free to choose their school and then their job. Therefore, the choice of school is one of the most important factors in choosing a successor. The focus of education should be related to the family business. We see from the survey that these successors also indirectly chose unions that relate to the family business. The knowledge of the successor is also related to education, which, in addition to the theoretical basis, is also related to practical experience. In the survey, the owners said that the successors have experience of working in the company. They relied on their knowledge, which they gradually expanded to be competent to take over the family business. Other important expressions were “family” and “son”. In the context of family businesses, it is natural that the owners emphasize the importance of the successor being from the family, as we found in the research. However, in the expression “son”, we see that in Slovak family businesses, sons are preferred as successors.

The choice of school, due to the possibility of becoming a successor, produced the same results as in the previous question on the lead of the successor to take over the family business. The owners positively assessed the involvement of potential successors in education (

Table 5) because it was their own decision. Therefore, this word was of the utmost importance in the subject of successor education. The owners said that they have the initiative to get involved in the company’s activities and bring several innovative ideas. They also want to take part in decision making in the company, which the owners also allow, but only to a considerable extent, adapted to their experience and possibilities, and accordingly, they are also entrusted with tasks. The younger successors were primarily concerned with being able to work alongside the school in a family business in the form of a part-time job, thus connecting theory with practice. As we see in

Table 5, the owners of the examples in education assigned a high weight to orientation to the field of business as well as to the interest of successors. As we also found out from the interviews, the successors themselves develop the initiative of education (up to 72.93%). The successors did not show interest in only 13.51% of the family businesses, which were micro companies. This fact was not affected by the age of the owner as well as the business or the gender of the owner. For the remaining number of owners, no successor was appointed, and therefore they could not comment on this issue. However, they said that when they choose a successor, they certainly want them to be educated in the form of work in a company. The last expression is the word task, which has great weight in practical training in a family business. By fulfilling the tasks of the owners, the owners can find out the practical skills of the successors.

Regarding the attitude of the current owner to the operation of the company after the process of generational exchange, only 51.35% of owners of family businesses plan to remain active in the company even after the process of generational exchange. In this fact, we found that the owners who want to stay active in the company even after a generational change are mainly aged 41 to 50 years and over 62 years. A total of 48.65% of owners want to withdraw from the management of the family business after the process of generational exchange, of which only 21.62% of owners want to leave the business completely and leave it to the successors. The remaining 21.62% of owners want to remain an advisory body for the successors after the generational transfer if necessary, and 5.41% of owners want to remain the controlling body of the company.

For the owners, providing help to the successor after the generational transfer had the greatest weight (

Table 6). The interviews showed that the owners are very attached to their business. They have been building it for years, and it is also a part of them. This implies the second most important term and that is the entrustment of the possibility of the next generation to grow the company. Successors have the possibility to try out the management of the company (under the owner) before the generational transfer. Therefore, after the generational transfer, the original owner should leave the management of the family business only to the successor. In our research, after generational exchange, owners offer successors the possibility to realize themselves, but they want to always be at hand and sell their experience. They also placed importance on the “successor” because the further survival of the family business will depend on them. The current owners have an emotional bond with the company, meaning they want to stay interested in it. Therefore, the term “helping hand” is among the most important expressions. Although the company will belong to the next generation, they have expressed an interest in being helpful in the company’s difficulties, especially shortly after the generational transfer. The term “management” represented the importance attached to the successor in the management of the business. If the successor fails to manage, the generational exchange will be unsuccessful.

5. Discussion

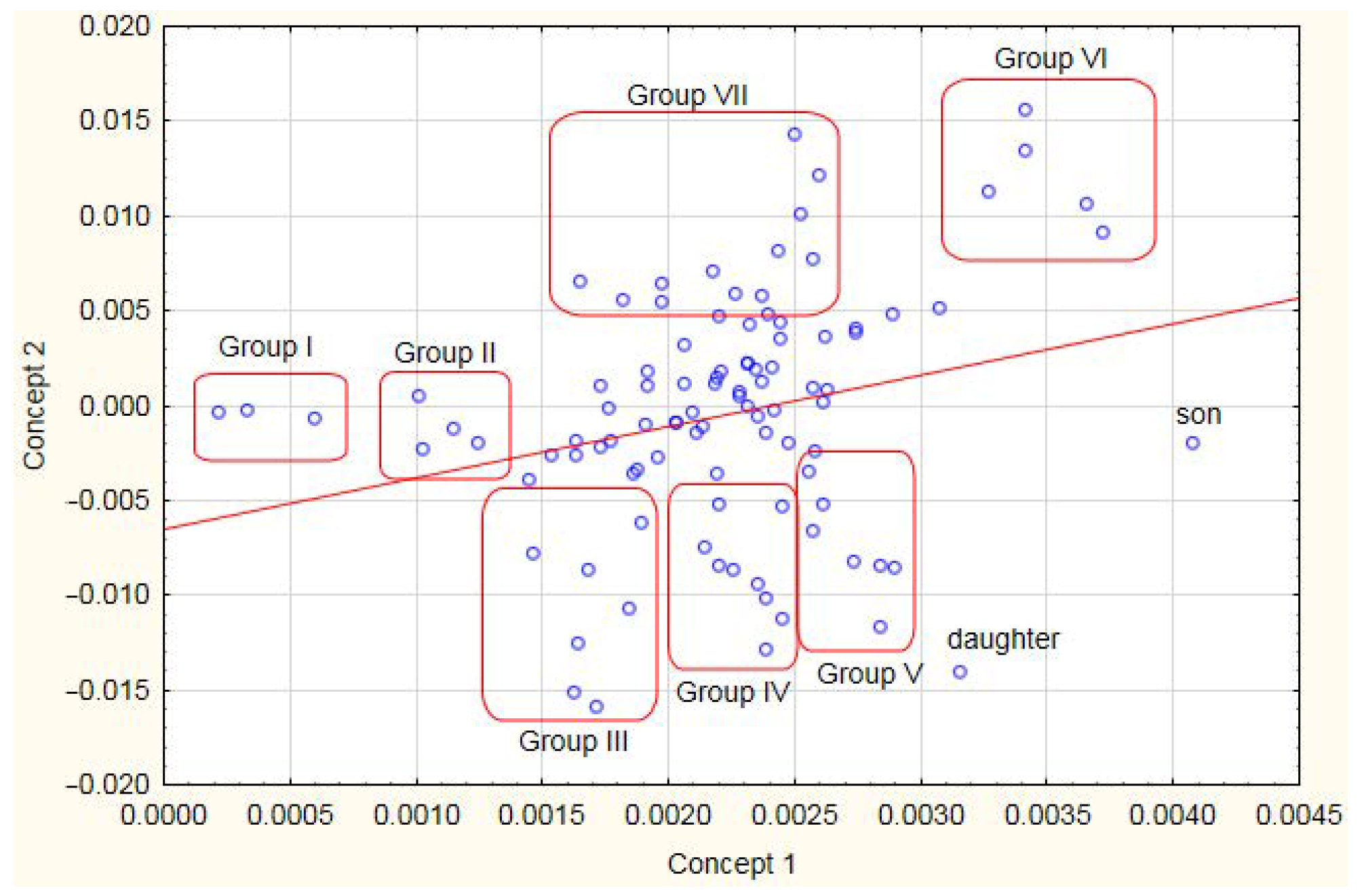

By extracting the concepts into a scatter chart, we learned that the owners of family businesses focused on the topic of succession:

Blending of the personal and professional lives of owners as well as their successors;

The need for succession planning in sufficient time in advance, particularly the establishment of a succession plan;

Launching a succession process that should affect the actual education of the potential successor;

The need to gain experience and knowledge in a family business before a generational transfer;

The very attitude of potential successors to generational exchange;

The need for stakeholder communication, thus eliminating the problems associated with the succession process;

Clarification of how the company will work after the generational exchange and what role the current owner still wants to play in it.

The most important expression on the issue of generational exchange in family businesses was the agreement between the owner and the successor, which corresponds to the research of

Sharma et al. (

2003). Succession planning has been the subject of much research around the world. We found that 70.27% of owners have no succession plan in place, and this figure is higher than that reported by

Effron and Ort (

2010), who claimed that it is only up to 70%. Just as Slovak family businesses underestimate planning and a plan, in the research of

Dalpiaz et al. (

2014), they found that this underestimation is also found in Italian family businesses.

Bąkiewicz (

2020) revealed that succession planning is also influenced by the status of a post-communist country. According to the Bąkiewicz, the specifics of such a cultural background are detrimental to the planning of succession in family businesses. Among the specifics of post-communist countries, Bąkiewicz mentioned individualism, short-term orientation, masculinity, avoiding high insecurity, the cultural gap between generations and even the assertiveness of millennia. Bąkiewicz supported his claim with research, where he found that in Poland, as a post-communist country, only 14% of family businesses have a succession plan, while in Indonesia, 92% have a plan.

Allioui et al. (

2021) again argued that the main resistance to succession planning is linked to psychological characteristics, which affect the owner’s willingness to resign from the company’s management. The term time was also associated with succession. The Slovak Business Agency (

SBA 2018) also pointed out that owners start to deal with succession only when the time to retire comes.

Family membership was an important factor in choosing a successor. Slovak owners preferred their own descendants as successors. This statement also corresponds to research in Taiwanese family businesses (

Luan et al. 2018).

Drewniak et al. (

2020) claimed, however, that an external successor can increase a family business’s sales. When owners prefer their own offspring, according to

Kandade et al. (

2021), their early affiliation to the family business is required. This affiliation can increase their socialization with stakeholders and provide a good environment for building relationships and creating emotional mutual respect and trust in the company. In this research, we found that owners prefer sons as successors, and this statement corresponds to

Wang (

2010), and

Ahrens et al. (

2015). In selecting a successor,

Drewniak et al. (

2020) pointed out that the successor should have the charisma and personality of a manager. They do not need to be an ideal copy of the current owner. It is also necessary to take into account education and knowledge, as we found out in this research. If a direct descendant of the owner is not suitable as a successor, the owner may divide the ownership and management of the family business (

Morris et al. 1997;

Takwi et al. 2020).

On the topic of successor education, we revealed that successors in Slovak family businesses are taking the initiative to learn (the expressions “decision” and “interest”), which corresponds to the results of the research of

Lušňáková et al. (

2019), who also focused on Slovak family businesses. Successors try to become involved in the day-to-day running of the company and thus gain practical experience.

Dhaenens et al. (

2018) recommended educating successors through mentoring.

Kandade et al. (

2021) found that mentoring in family businesses creates a quality relationship between the mentor and the mentee, which affects the faster socialization of the successor. Mentoring can improve the interpersonal relationship between the owner and the successor. This statement also corresponds to research in the social field of family businesses (

Zellweger et al. 2019). According to research, early belonging to a family business helps successors to gain solid knowledge in education (

Samara and Arenas 2017) and increase experience (

Miller et al. 2011).

The last area we focused on was the transfer of a business from owner to successor. This phase is the most critical, and many family businesses cease to exist after it (

Bennedsen et al. 2015). Our research shows that up to 51.35% of current owners want to stay in the family business after a generational transfer. This is also evidenced by the importance of expressions such as “help”, “possibility” and “helping hand”. Our results correspond to the statements of

Filser et al. (

2013) and

Gagnè et al. (

2011).

Allioui et al. (

2021) argued that it is the timely planning of a generational change that can help to ensure a smooth transition of ownership. The reason for the reluctance of the owner to leave the business was considered to be that the owners could not disengage from the family business because they did not have time to perform hobbies in addition to their daily work.

Kandade et al. (

2021) stated that the level of trust in the successor may be an important factor in staying in the company. Therefore, owners should not underestimate the planning and determine, in advance, when the successor should join the family business.

Morris et al. (

1997) focused on research into successful family business managers and revealed that succession was successful if successors were properly prepared for their new role. The readiness consisted of their academic background and the diversity of work experience in a family business.

6. Conclusions

Although family businesses are the most widespread form of business, in Slovakia, family businesses began to emerge only after 1989 due to the political situation. While the first generational exchanges have been taking place in Slovakia in recent years, this process has been common in the world for several decades to centuries. In Slovakia, it was only in this period that SME support institutions began to address the issue of succession in family businesses. However, all the world’s research has one thing in common: most family businesses will not survive a generational change. For this reason, the aim of this paper was to evaluate the attitude of Slovak family companies to the succession process and to reveal the risk factors that affect this process.

Based on the results of this research, we found that more than 50% of family businesses have not yet started to address the issue of succession. Although owners emphasized the importance of how long they have until retirement, they should be aware that this process is long term and can take up to 15 years (

Hešková and Vojtko 2008). Therefore, we consider the postponement of the start of the succession process to be the first risk factor. An important point after starting the process is to draw up a succession plan. We therefore recommend drawing up a plan, especially in writing, as its importance in research has been elucidated, and consulting it with experts. Therefore, we consider leaving the succession to be free without a specified plan as the second risk factor. While it may seem that micro and small business owners do not need this plan, the opposite is true. During the discussion, we found that post-communist countries have a greater problem with succession planning than family businesses in other countries.

In this research, we found that the owners of Slovak family businesses prefer their own descendants as successors, which we also see in

Table 4. One of the surprising findings is that in the age of globalization, management positions are still attributed mainly to male descendants, which we have seen in the importance of the term “son”. As many as 59.46% of successors were led to take over the family business from childhood. It is also necessary to address the issue of school selection during the student years when choosing a successor.

Based on the results, we consider the selection of a suitable successor as another risk factor. The successor does not have to only be male, or only a direct descendant. Owners should evaluate the abilities of their offspring and use them to select a suitable successor. However, if the direct descendant is not suitable as the successor in the management of the company, the owner may leave the management to a professional manager, and the direct descendant will not be bound by the management of the company or only by their ownership. Leading direct descendants in a family business from childhood can increase their competence to run a family business, as confirmed by foreign research. Therefore, we consider the late affiliation of the successor to the family business as another risk factor.

In addition to the abilities of successors, we also consider their attitude to generational change to be a risk factor. If the direct descendant is not interested in taking over the family business or has a different vision of the direction of the business from the owner, the owner should also consider choosing another successor.

In our research, the initiative to gain education, especially for successors, manifested itself in the topic of education. Based on this research, we did not notice any negative factors that are found in family businesses in Slovakia in the education of successors. However, the willingness to learn does not yet guarantee the success of a generational transfer. Therefore, we consider the personality of the successor to be a risk factor. We recommend owners to evaluate successors also on the basis of personality and soft skills. This factor is also related to the abilities of the successors, which we addressed above. Managerial skills are important in leading any team, not just a family business. It is the personality of the successor that can be a factor that prevents the company’s demise. We recommend revealing weak personality traits and working on them before the generational transfer. In education, we consider another risk point, regarding the need for diverse practical experience in the company as well as outside the company. Working outside a family business, the successor can bring innovative practices and ideas to the business.

On the topic of generational transfer, up to 51.35% of owners wanted to remain active in running the family business. We also consider this fact to be risky. Although this may seem to reduce the risk of default, if the owner decides to leave the business to a successor, they should no longer interfere in the management of the business unless requested by the successor. This avoids the frustration of the successor and demotivation to continue running the business. We recommend that before the generational transfer, the owner and the successor should agree on what the company’s management will look like after it.

Based on the extraction of concepts, we found that, in addition to the above topics, succession is influenced by family conflicts and the connection between work and private life. Therefore, we consider communication at a sufficient level to be the last risk factor from our research.

These factors are influenced by the culture, demographic and religious culture of a given geographical area, and thus we consider them to be a contribution to the succession process for a specific geographical area. By focusing on family business owners and given risk factors, it can increase the success of generational change in a company.

Based on the results of the structured guided interviews, we evaluated the established research assumptions:

Succession is an important topic for family businesses not only in Slovakia but also elsewhere. Various studies have revealed that a sizable percentage of family businesses do not survive generational exchanges. Therefore, it is important not only to address this issue in academia but also to make family businesses aware of the importance of the succession process.

We consider the results of this research from Slovak family businesses to be beneficial due to the fact that we focused on the succession process in a country that belongs to the post-communist countries, and thus the current owners of family businesses are significantly affected. As

Botero et al. (

2015) stated, most of the literature on family entrepreneurship is developed in a North American context. Therefore, the results of our research contribute to information on the succession of family businesses in the European context.

We focused our research on family business owners. We see the potential for further research in the implementation of similar research on potential successors of family businesses. We also see the potential for further research on the former owners and successors of family businesses, where the family business has disappeared through a generational transfer.