Offsetting Risk in a Neoliberal Environment: The Link between Asset-Based Welfare and NIMBYism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Typology for Understanding Trends in Housing and Public Pension Policies across Nations

3. The Neoliberal Preference for Homeownership

4. Homeownership as Asset-Based Welfare

This underpins the broader commodification of social relations, with market practices constituted as the best and most appropriate means of welfare provision, and state mediation the least. This inevitably supports the reduction of public spending and the transfer of economic and social risks from the state to individuals, which underlie a more globalized model of a competitive and market-orientated neo-liberal state.(p. 12)

[H]ousing wealth is not wealth on the aggregate level … Rising house prices are advantageous for individual house owners ... [t]hey are however disadvantageous for (potential) house buyers and for renters insofar as rental prices co-move with house prices. Rising prices redistribute and do not add to total production and economic growth ... [c]hanging house prices lead to unpredictable, unfair and inefficient redistribution of wealth.

5. Asset-Based Welfare as an Incentive for Exclusionary Land Use

6. Conclusions

Breton (1973) invoked economic theory to explain the existence of zoning and the difficulties it posed for developers. He identified the cause of residents’ aversion to development as an incomplete insurance market. Since residents cannot insure against neighborhood change, zoning offers a kind of second-best institution. If homeowners were insured against neighborhood decline, they wouldn’t worry so much about seemingly unlikely scenarios and behave like NIMBYs.(p. 145)

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

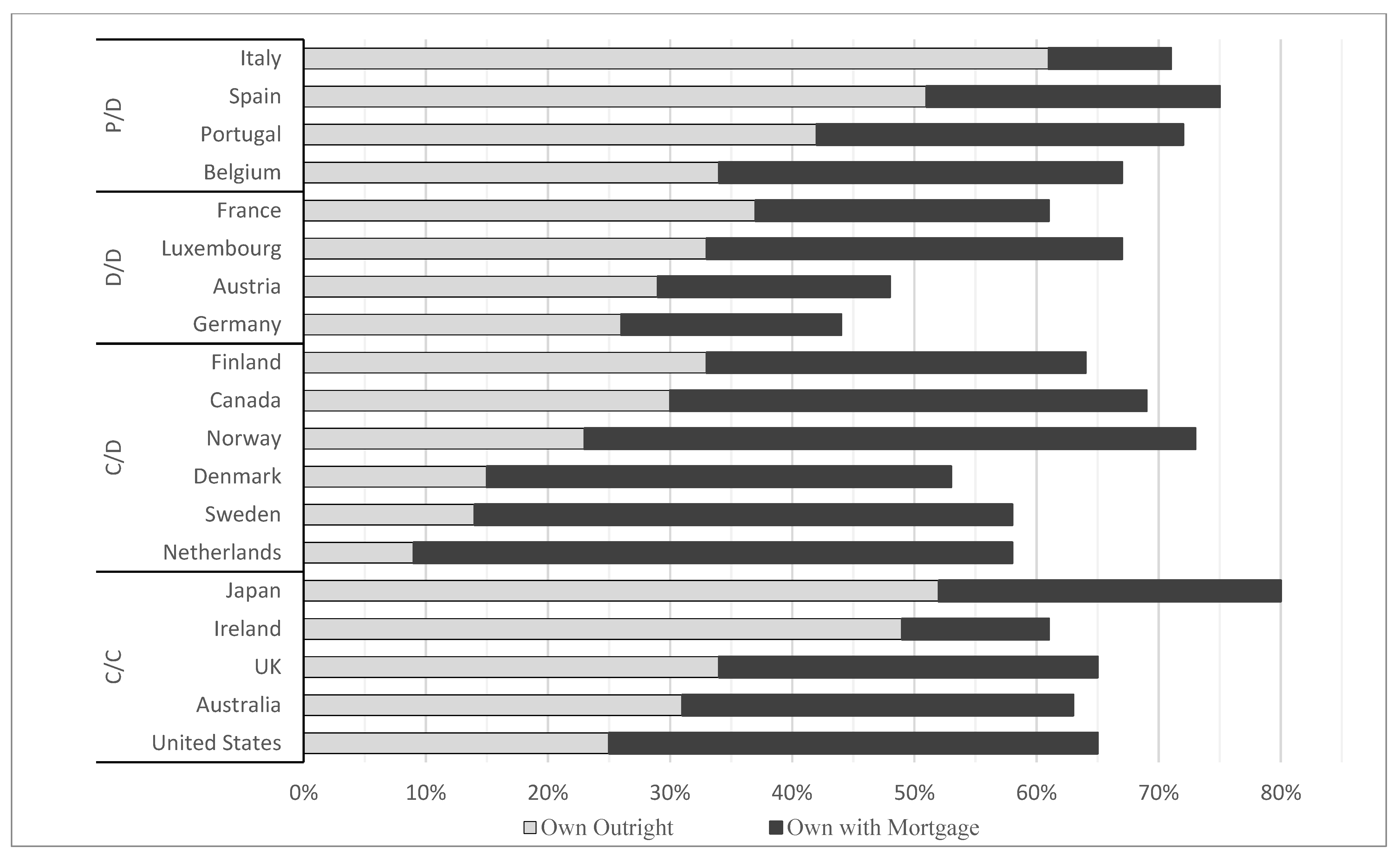

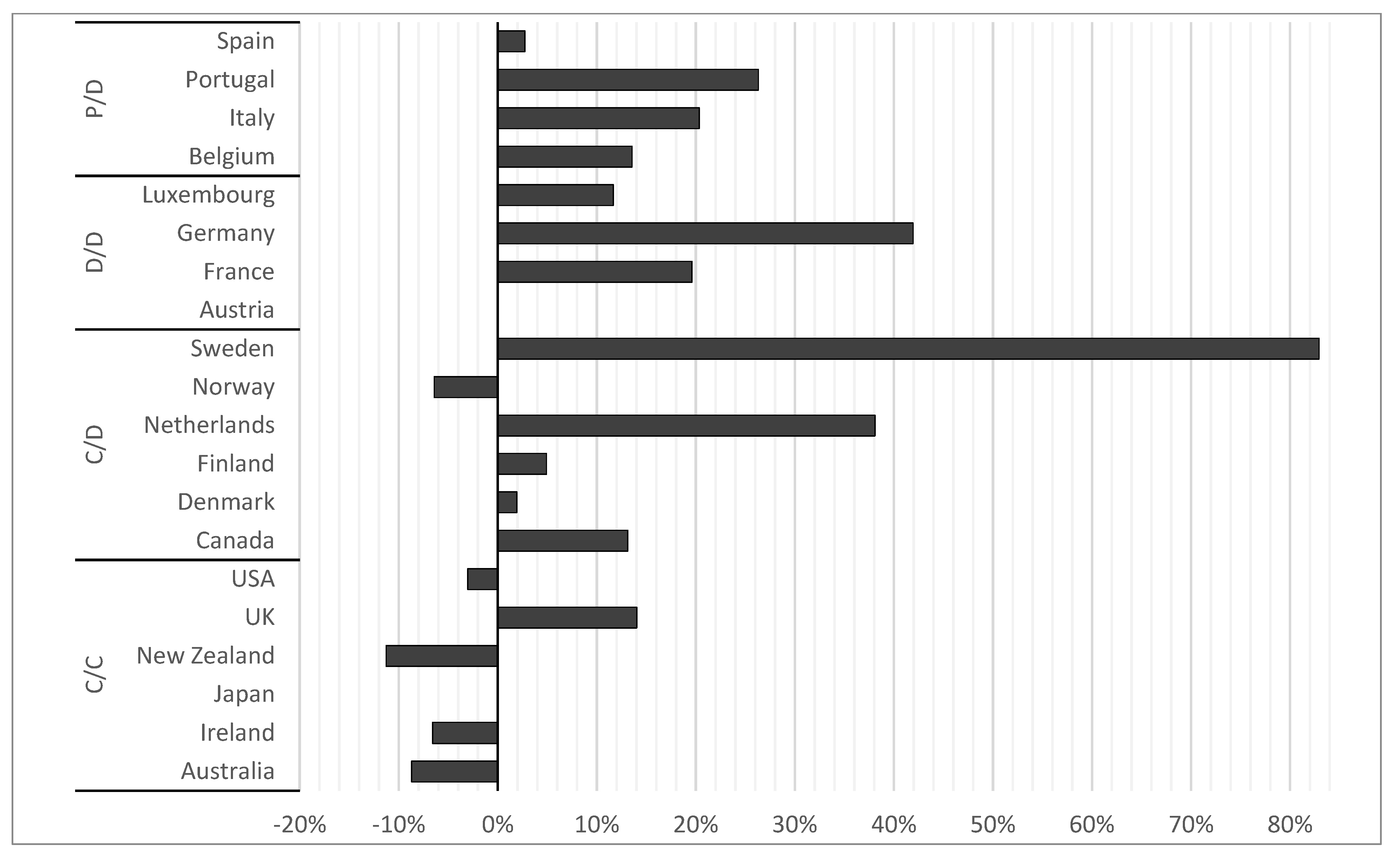

| 1 | Only suggestive because while it is possible to track long-term trends in homeownership rates to an extent, data on the prevalence home-debtors over time is scant. |

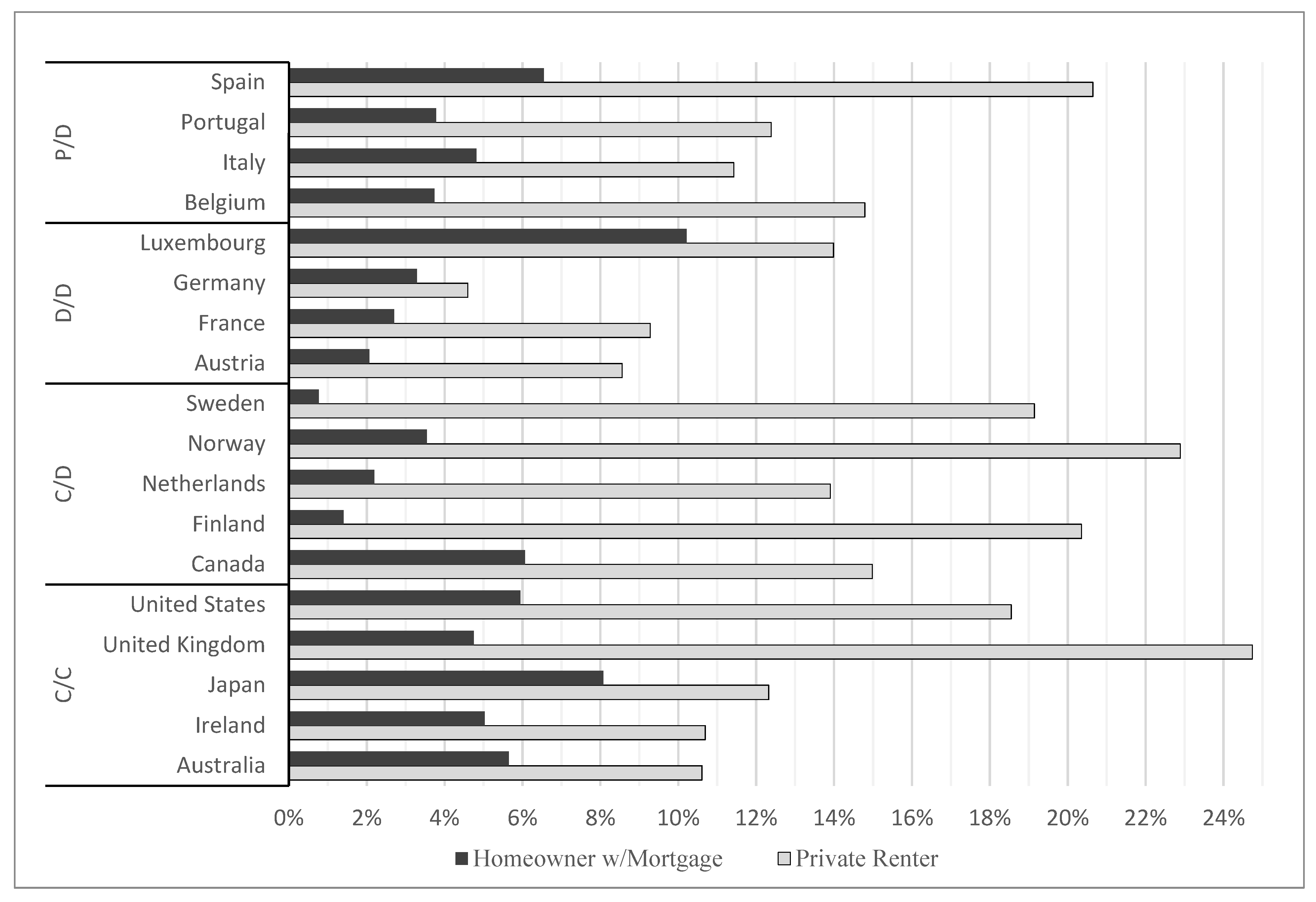

| 2 | Individual data sources for Figure 2: (Anacker et al. 2019; Central Statistics Office 2016; Davis et al. 2008; Doling and Elsinga 2012; Kettenhofen 2021; Statistics Canada 2021). |

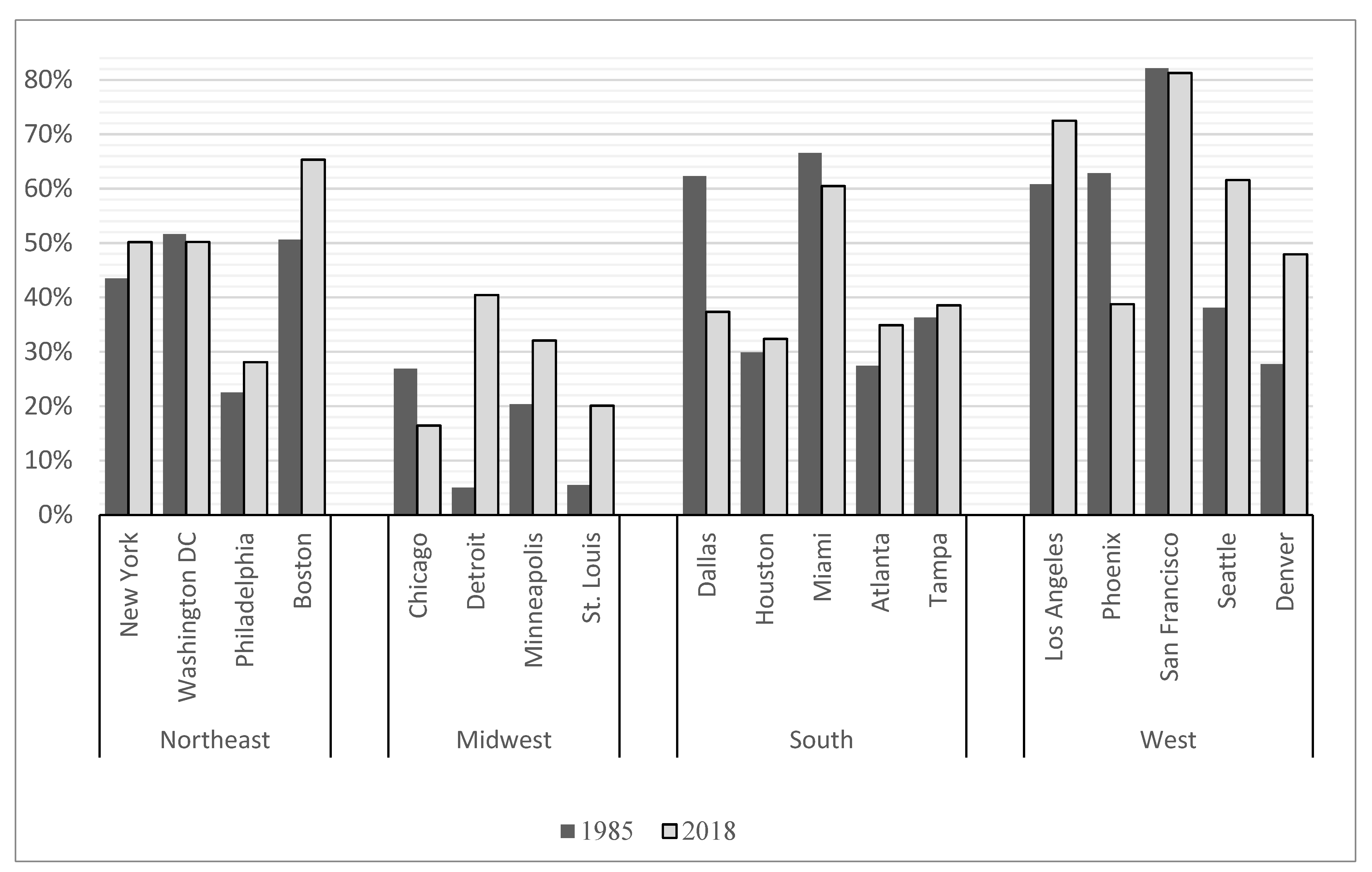

| 3 | One possible exception to this may be Chicago which saw land drop as a percentage of homes built and, generally, does not follow a development pattern similar to cities like Dallas and Pheonix. Exploring this specific case in greater detail, however, is beyond the scope of this paper. |

| 4 | Mirowski and Plehwe (2015) would point out that neoliberal ideology is not opposed to government interventions that prop up markets or protect stocks of wealth. |

References

- Aalbers, Manuel B. 2009. The Sociology and Geography of Mortgage Markets: Reflections on the Financial Crisis. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 33: 281–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalbers, Manuel B. 2011. Place, Exclusion and Mortgage Markets. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, vol. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Aalbers, Manuel B. 2015. The Great Moderation, the Great Excess and the Global Housing Crisis. International Journal of Housing Policy 15: 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Enterprise Institute. 2021. Historical Land Price Indicators. American Enterprise Institute-AEI (blog). Available online: https://www.aei.org/historical-land-price-indicators/ (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Amior, Michael, and Jonathan Halket. 2014. Do Households Use Home-Ownership to Insure Themselves? Evidence across US Cities. Quantitative Economics 5: 631–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anacker, Katrin B., Mai Thi Nguyen, and David P. Varady. 2019. The Routledge Handbook of Housing Policy and Planning. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- André, Stéfanie, and Caroline Dewilde. 2016. Home Ownership and Support for Government Redistribution. Comparative European Politics 14: 319–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badger, Emily, and Quoctrung Bui. 2019. Cities Start to Question an American Ideal: A House with a Yard on Every Lot. The New York Times. June 18 The Upshot. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/06/18/upshot/cities-across-america-question-single-family-zoning.html (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Beer, Andrew, and Debbie Faulkner. 2011. Housing Transitions through the Life Course: Aspirations, Needs and Policy. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal, Pamela M., John R. McGinty, and Rolf Pendall. 2016. Strategies for Increasing Housing Supply in High-Cost Cities. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, Tyler, and Dan Doonan. 2020. The Growing Burden of Retirement. National Institute on Retirement Security. Available online: https://www.nirsonline.org/reports/growingburden/ (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1998. Neo-Liberalism, the Utopia (Becoming a Reality) of Unlimited Exploitation. In Acts of Resistance: Against the Tyrranny of the Market. France: Blackwell Publishers Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Brainard, Keith, and Alex Brown. 2018. Significant Reforms to State Retirement Systems. National Association of State Retirement Administrators. Available online: https://www.nasra.org/files/Spotlight/Significant%20Reforms.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Brennan, Maya, Pam Blumenthal, Laurie Goodman, Ellen Seidman, and Brady Meixell. 2017. Housing as an Asset Class. Available online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/93601/housing-as-an-asset-class_0.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Breton, A. 1973. Neighborhood Selection and Zoning. In Issues in Urban Public. Edited by Harold Hochman. Saarbrucken: Institute Internationale de Finance Publique. [Google Scholar]

- Castles, Francis G. 1998. The Really Big Trade-off: Home Ownership and the Welfare State in the New World and the Old. Acta Politica 33: 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Causa, Orsetta, Nicolas Woloszko, and David Leite. 2019. Housing, Wealth Accumulation and Wealth Distribution: Evidence and Stylized Facts. OECD Economics Department Working Papers 1588. OECD Economics Department Working Papers. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/housing-wealth-accumulation-and-wealth-distribution-evidence-and-stylized-facts_86954c10-en (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Central Statistics Office. 2016. Census of Population 2016–Profile 1 Housing in Ireland. Available online: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cp1hii/cp1hii/hs/ (accessed on 21 January 2019).

- Cerny, Philip G. 2008. Embedding Neoliberalism: The Evolution of a Hegemonic Paradigm. The Journal of International Trade and Diplomacy 2: 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chia, Ngee Choon, and Albert K. C. Tsui. 2019. Nexus between Housing and Pension Policies in Singapore: Measuring Retirement Adequacy of the Central Provident Fund. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 18: 304–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophers, Brett. 2013. A Monstrous Hybrid: The Political Economy of Housing in Early Twenty-First Century Sweden. New Political Economy 18: 885–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clingermayer, James C. 2004. Heresthetics and Happenstance: Intentional and Unintentional Exclusionary Impacts of the Zoning Decision-Making Process. Urban Studies 41: 377–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Sarah. 2001. Addressing Vulnerability through Asset Building and Social Protection. In Asset-Based Welfare: International Comparisons. Edited by Sue Regan and Will Paxton. London: IPPR. [Google Scholar]

- Crook, Tony, and Peter A. Kemp. 2011. Transforming Private Landlords: Housing, Markets and Public Policy. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, vol. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, Colin. 2011. The Strange Non-Death of Neo-Liberalism. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Morris A., Andreas Lehnert, and Robert F. Martin. 2008. The Rent-Price Ratio for the Aggregate Stock of Owner-Occupied Housing. Review of Income and Wealth 54: 279–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Morris A., and Michael G. Palumbo. 2008. The Price of Residential Land in Large US Cities. Journal of Urban Economics 63: 352–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Decker, Pascal, and Caroline Dewilde. 2010. Home-Ownership and Asset-Based Welfare: The Case of Belgium. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 25: 243–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfani, Neda, Johan De Deken, and Caroline Dewilde. 2014. Home-Ownership and Pensions: Negative Correlation, but No Trade-Off. Housing Studies 29: 657–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F. Frederic. 2003. The Rebound of Private Zoning: Property Rights and Local Governance in Urban Land Use. Environment and Planning A 35: 133–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewilde, Caroline, and Pascal De Decker. 2016. Changing Inequalities in Housing Outcomes across Western Europe. Housing, Theory and Society 33: 121–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Feliciantonio, Cesare, and Manuel B. Aalbers. 2018. The Prehistories of Neoliberal Housing Policies in Italy and Spain and Their Reification in Times of Crisis. Housing Policy Debate 28: 135–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, Robert D., and Donald R. Haurin. 2003. The Social and Private Micro-Level Consequences of Homeownership. Journal of Urban Economics 54: 401–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doling, John, and Marja Elsinga. 2012. Demographic Change and Housing Wealth: Home-Owners, Pensions and Asset-Based Welfare in Europe. Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Elledge, Jonn. 2016. Treat Houses as Assets Rather than Homes and This Is What Happens|Jonn Elledge. The Guardian. February 12. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/feb/12/houses-assets-homes-housing-tenants-evicted (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Elsinga, Marja, and Joris Hoekstra. 2015. The Janus Face of Homeownership-Based Welfare. Critical Housing Analysis 2: 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elster, J. 1986. The Market and the Forum: Three Varieties of Political Theory. In Foundations of Social Choice Theory. Edited by J. Elster and A. Hyland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- England, Kim, and Kevin Ward. 2016. Theorizing Neoliberalization. In Handbook of Neoliberalism. Edited by Simon Springer, Kean Birch and Julie MacLeavy. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Esaiasson, Peter. 2014. NIMBYism–A Re-Examination of the Phenomenon. Social Science Research 48: 185–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Alan W. 2008. Economics and Land Use Planning. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson, Alan. 2009. Financialisation, Financial Literacy and Asset-Based Welfare. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 11: 400–421. [Google Scholar]

- Fischel, William A. 2001. Why Are There NIMBYs? Land Economics 77: 144–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischel, William A. 2004. An Economic History of Zoning and a Cure for Its Exclusionary Effects. Urban Studies 41: 317–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, Ray, and Ngai Ming Yip. 2011. Housing Markets and the Global Financial Crisis: The Uneven Impact on Households. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, Ray, and Yosuke Hirayama. 2015. The Financialisation of the Social Project: Embedded Liberalism, Neoliberalism and Home Ownership. Urban Studies 52: 233–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, James C., and Edward L. Kick. 2007. The Role of Public, Private, Non-Profit and Community Sectors in Shaping Mixed-Income Housing Outcomes in the US. Urban Studies 44: 2357–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilderbloom, Ji, and Jp Markham. 1995. The Impact of Homeownership on Political Beliefs. Social Forces 73: 1589–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, Edward L., and Bryce A. Ward. 2009. The Causes and Consequences of Land Use Regulation: Evidence from Greater Boston. Journal of Urban Economics 65: 265–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, Edward L., Joseph Gyourko, and Raven E. Saks. 2005. Why Have Housing Prices Gone Up? American Economic Review 95: 329–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, Edward G. 2013. New Deal Ruins: Race, Economic Justice, and Public Housing Policy. New York: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gurran, Nicole, and Glen Bramley. 2017. Urban Planning and the Housing Market: International Perspectives for Policy and Practice. London: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hackworth, Jason. 2007. The Neoliberal City: Governance, Ideology, and Development in American Urbanism. New York: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haffner, Marietta E.A. 2009. Bridging the Gap between Social and Market Rented Housing in Six European Countries? Amsterdam: IOS Press, vol. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson, Michael. 2018. When Do Renters Behave like Homeowners? High Rent, Price Anxiety, and NIMBYism. American Political Science Review 112: 473–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, John F. 1996. Colonial Land Use Law and Its Significance for Modern Takings Doctrine. Harvard Law Review 109: 1252–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, Douglas A., Kène Henkens, and Hendrik P. Van Dalen. 2007. Mapping the Minds of Retirement Planners: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 38: 361–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilber, Christian A.L. 2010. New Housing Supply and the Dilution of Social Capital. Journal of Urban Economics 67: 419–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hodkinson, Stuart. 2011. Housing Regeneration and the Private Finance Initiative in England: Unstitching the Neoliberal Urban Straitjacket. Antipode 43: 358–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollanders, David. 2016. Pension Systems Do Not Suffer from Ageing or Lack of Home-Ownership but from Financialisation. International Journal of Housing Policy 16: 404–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hsieh, Chang-Tai, and Enrico Moretti. 2015. Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation. w21154. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlanfeldt, Keith R. 2004. Exclusionary Land-Use Regulations within Suburban Communities: A Review of the Evidence and Policy Prescriptions. Urban Studies 41: 261–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlanfeldt, Keith R. 2007. The Effect of Land Use Regulation on Housing and Land Prices. Journal of Urban Economics 61: 420–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

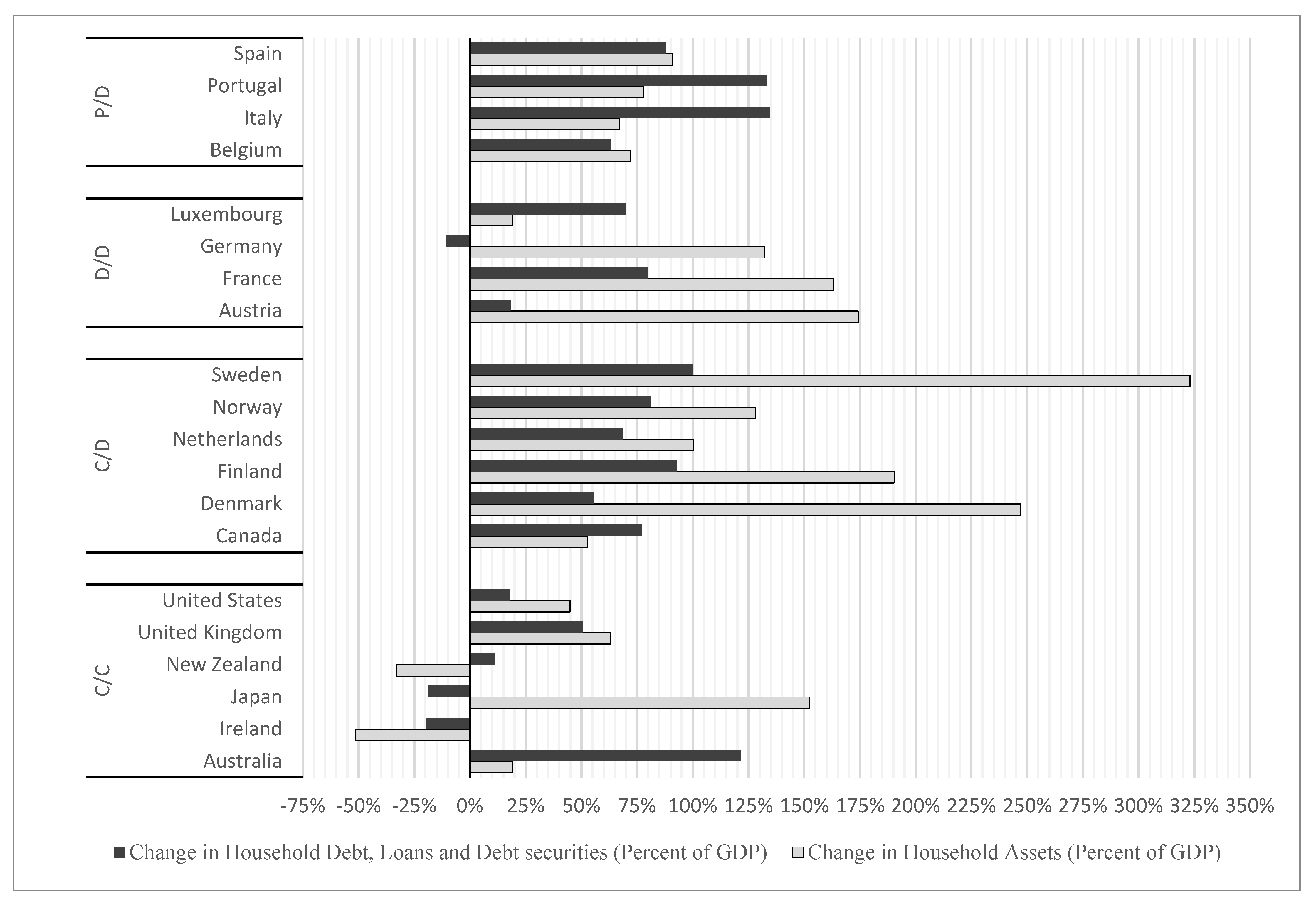

- International Monetary Fund. 2020. Household Debt, Loans and Debt Securities. IMF Global Debt Database. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/HH_LS@GDD (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Izuhara, Misa. 2016. Reconsidering the Housing Asset-Based Welfare Approach: Reflection from East Asian Experiences. Social Policy and Society 15: 177–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeszeck, Charles A., Margie K Shields, Justine Augeri, Christina Cantor, Gustavo Fernandez, Jennifer Gregory, Adam Wendel, and Seyda Wentworth. 2017. The Nation’s Retirement System: A Comprehensive Re-Evaluation Is Needed to Better Promote Future Retirement Security. Government Accountability Office. Available online: https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3062574 (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Jones, Colin, and Craig Watkins. 2009. Housing Markets and Planning Policy. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, vol. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Kadi, Justin, and Richard Ronald. 2016. Undermining Housing Affordability for New York’s Low-Income Households: The Role of Policy Reform and Rental Sector Restructuring. Critical Social Policy 36: 265–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadi, Justin, and Sako Musterd. 2015. Housing for the Poor in a Neo-Liberalising Just City: Still Affordable, but Increasingly Inaccessible. Journal of Economic and Social Geography 106: 246–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemeny, Jim. 1980. Home Ownership and Privatization. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 4: 372–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemeny, Jim. 2005. ‘The Really Big Trade-Off’ between Home Ownership and Welfare: Castles’ Evaluation of the 1980 Thesis, and a Reformulation 25 Years On. Housing, Theory & Society 22: 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettenhofen, L. 2021. Japan: Home Ownership Rate 1973–2018. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1005428/home-ownership-rate-japan/ (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Kingston, Pw, and Jc Fries. 1994. Having a Stake in the System-the Sociopolitical Ramifications of Business and Home Ownership. Social Science Quarterly 75: 679–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyotaki, Nobuhiro, Alexander Michaelides, and Kalin Nikolov. 2011. Winners and Losers in Housing Markets. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 43: 255–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, Katharina, Moritz Schularick, and Thomas Steger. 2017. No Price like Home: Global House Prices, 1870–2012. American Economic Review 107: 331–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köppe, Stephan. 2015. Housing Wealth and Asset-Based Welfare as Risk. Critical Housing Analysis 2: 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwin, Howard, and Adi Meir. 2013. Financial Worry among Older People: Who Worries and Why? Journal of Aging Studies 27: 113–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeavy, Julie. 2016. Neoliberalism and Welfare. In Handbook of Neoliberalism. Edited by Simon Springer, Kean Birch and Julie MacLeavy. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Malpass, Peter. 2008. Histories of Social Housing: A Comparative Approach. In Social Housing in Europe II. Edited by Kathleen Scanlon and Christine Whitehead. London: London School of Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Matejczyk, Anthony P. 2001. Why Not NIMBY? Reputation, Neighbourhood Organisations and Zoning Boards in a US Midwestern City. Urban Studies 38: 507–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, Brian J. 2016. No Place Like Home: Wealth, Community, and the Politics of Homeownership. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, Zhan, and Kim McKee. 2012. Creating Sustainable Communities through Tenure-Mix: The Responsibilisation of Marginal Homeowners in Scotland. GeoJournal 77: 235–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, Kim. 2012. Young People, Homeownership and Future Welfare. Housing Studies 27: 853–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirowski, Philip. 2013. Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown. New York: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowski, Philip. 2018. Neoliberalism: The Movement that Dare Not Speak Its Name. American Affairs Journal. February 20. Available online: https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2018/02/neoliberalism-movement-dare-not-speak-name/ (accessed on 2 July 2019).

- Mirowski, Philip, and Dieter Plehwe. 2015. The Road from Mont Pelerin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Monbiot, George. 2016. How Did We Get into This Mess?: Politics, Equality, Nature. New York: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomerie, Johnna, and Mirjam Büdenbender. 2015. Round the Houses: Homeownership and Failures of Asset-Based Welfare in the United Kingdom. New Political Economy 20: 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, Stefano. 2016. Interventionist Responsibilities for the Emergence of the US Housing Bubble and the Economic Crisis: ‘Neoliberal Deregulation’ Is Not the Issue. European Planning Studies 24: 1295–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munck, Ronaldo. 2003. Neoliberalism, Necessitarianism and Alternatives in Latin America: There Is No Alternative (TINA)? Third World Quarterly 24: 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2019. Affordable Housing. In Society at a Glance 2019: OECD Social Indicators. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2021a. Household Accounts-Household Financial Assets. Available online: http://data.oecd.org/hha/household-financial-assets.htm (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- OECD. 2021b. Pension Spending (Indicator). Available online: http://data.oecd.org/socialexp/pension-spending.htm (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- OECD Affordable Housing Database. 2021a. OECD Affordable Housing Database. Housing Costs over Income. OECD Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs-Social Policy Division (blog). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/els/family/HC1-2-Housing-costs-over-income.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- OECD Affordable Housing Database. 2021b. Housing Tenures. OECD Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs-Social Policy Division (blog). 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/els/family/HC1-2-Housing-costs-over-income.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Plehwe, Dieter. 2016. Neoliberal Hegemony. In Handbook of Neoliberalism. Edited by Simon Springer, Kean Birch and Julie MacLeavy. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, Russell. 2016. Neoliberalism Everywhere: Mobile Neoliberal Policy. In Handbook of Neoliberalism. Edited by Simon Springer, Kean Birch and Julie MacLeavy. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ronald, Richard. 2008. The Ideology of Home Ownership: Homeowner Societies and the Role of Housing. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ronald, Richard, and Caroline Dewilde. 2017. Why Housing Wealth and Welfare? In Housing Wealth and Welfare. Gloucestershire: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell, Jonathan, and Douglas S. Massey. 2009. The Effect of Density Zoning on Racial Segregation in US Urban Areas. Urban Affairs Review 44: 779–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusch, Lara. 2012. New Neighbors, Old Neighborhood: Affordable Homeownership and Engagement in an East Detroit Neighborhood. Spaces and Flows: An International Journal of Urban and ExtraUrban Studies 3: 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan-Collins, Josh, Toby Lloyd, and Laurie Macfarlane. 2017. Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing. London: Zed Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Saegert, Susan, Desiree Fields, and Kimberly Libman. 2009. Deflating the Dream: Radical Risk and the Neoliberalization of Homeownership. Journal of Urban Affairs 31: 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, Tore. 2011. Neo-Liberal Urban Planning Policies: A Literature Survey 1990–2010. Progress in Planning 76: 147–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, Anna M., George C. Galster, and Peter Tatian. 2001. Assessing the Property Value Impacts of the Dispersed Subsidy Housing Program in Denver. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management: The Journal of the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management 20: 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, Ana C. 2016. Financialisation, Social Provisioning and Well-Being in Five EU Countries. FESSUD Working Paper Series 176. Available online: https://estudogeral.sib.uc.pt/handle/10316/40972 (accessed on 13 November 2018).

- Schively, Carissa. 2007. Understanding the NIMBY and LULU Phenomena: Reassessing Our Knowledge Base and Informing Future Research. Journal of Planning Literature 21: 255–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Alex F. 2010. Trends, Patterns, Problems. In Housing Policy in the United States. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Herman, and Leonard Seabrooke. 2008. Varieties of Residential Capitalism in the International Political Economy: Old Welfare States and the New Politics of Housing. Comparative European Politics 6: 237–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherraden, Michael, ed. 2005. Inclusion in the American Dream: Assets, Poverty, and Public Policy. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sowell, Thomas. 2011. The Housing Boom and Bust. New York: Basic Books, Revised edition. [Google Scholar]

- Springer, Simon, Kean Birch, and Julie MacLeavy. 2016. An Introduction to Neoliberalism. In Handbook of Neoliberalism. Edited by Simon Springer, Kean Birch and Julie MacLeavy. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. 2021. Canada Home Ownership Rate|1997–2018 |Data|2020–2021 Forecast|Historical|Chart. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/canada/home-ownership-rate (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Stephens, Mark, Martin Lux, and Petr Sunega. 2015. Housing: Asset-Based Welfare or the ‘Engine of Inequality’? Critical Housing Analysis 2: 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touraine, Alain. 2001. Beyond Neoliberalism. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Walks, Alan, and Brian Clifford. 2015. The Political Economy of Mortgage Securitization and the Neoliberalization of Housing Policy in Canada. Environment and Planning 47: 1624–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, Matthew. 2009. Planning for a Future of Asset-Based Welfare? New Labour, Financialized Economic Agency and the Housing Market. Planning, Practice & Research 24: 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wind, Barend, Philipp Lersch, and Caroline Dewilde. 2017. The Distribution of Housing Wealth in 16 European Countries: Accounting for Institutional Differences. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 32: 625–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolsink, Maarten. 2004. Policy Beliefs in Spatial Decisions: Contrasting Core Beliefs Concerning Space-Making for Waste Infrastructure. Urban Studies 41: 2669–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2021. Population Ages 65 and above, Total|Data. World Bank Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.65UP.TO (accessed on 30 June 2021).

| Doling and Elsinga (2012) | Delfani et al. (2014) | |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | Corporatist | Decommodified Housing/Decommodified Pension System (D/D) |

| France | Corporatist | Decommodified Housing/Decommodified Pension System (D/D) |

| Germany | Corporatist | Decommodified Housing/Decommodified Pension System (D/D) |

| Luxembourg | — | Commodified Housing/Decommodified Pension System (D/D) |

| Belgium | Corporatist | Decommodified Housing/Decommodified Pension System (P/D) |

| Netherlands | Corporatist | Precommodified Housing/Decommodified Pension System (C/D) |

| Denmark | Social democratic | Commodified Housing/Decommodified Pension System (C/D) |

| Finland | Social democratic | Commodified Housing/Decommodified Pension System (C/D) |

| Sweden | Social democratic | Commodified Housing/Decommodified Pension System (C/D) |

| Canada | — | Commodified Housing/Decommodified Pension System (C/D) |

| Norway | — | Commodified Housing/Decommodified Pension System (C/D) |

| Italy | Mediterranean | Precommodified Housing/Decommodified Pension System (P/D) |

| Portugal | Mediterranean | Precommodified Housing/Decommodified Pension System (P/D) |

| Spain | Mediterranean | Precommodified Housing/Decommodified Pension System (P/D) |

| US | Liberal | Commodified Housing/Commodified Pension System (C/C) |

| UK | Liberal | Commodified Housing/Commodified Pension System (C/C) |

| Australia | — | Commodified Housing/Commodified Pension System (C/C) |

| Ireland | — | Commodified Housing/Commodified Pension System (C/C) |

| Japan | — | Commodified Housing/Commodified Pension System (C/C) |

| New Zealand | — | Commodified Housing/Commodified Pension System (C/C) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Record, M.C. Offsetting Risk in a Neoliberal Environment: The Link between Asset-Based Welfare and NIMBYism. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2021, 14, 547. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14110547

Record MC. Offsetting Risk in a Neoliberal Environment: The Link between Asset-Based Welfare and NIMBYism. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2021; 14(11):547. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14110547

Chicago/Turabian StyleRecord, Matthew C. 2021. "Offsetting Risk in a Neoliberal Environment: The Link between Asset-Based Welfare and NIMBYism" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14, no. 11: 547. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14110547

APA StyleRecord, M. C. (2021). Offsetting Risk in a Neoliberal Environment: The Link between Asset-Based Welfare and NIMBYism. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(11), 547. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14110547