1. Introduction

Responding to existential dilemmas, the COVID-19 pandemic calls for a major transdisciplinary research effort that necessarily combines several levels of empirical analysis and methodological tools (statistical, experimental, qualitative, comparative, interpretative) and bridges distinct academic and scientific traditions. The questions raised by COVID-19 are germane to the medical and the social sciences. From an international relations perspective, COVID-19 gets to the heart of what comprises a common good—the global commons. From a public policy perspective, COVID-19 is the wicked policy problem par excellence, requiring interagency collaboration. From a comparative politics perspective, COVID-19 provides a vast living dataset to engage in multilevel comparisons and real-time experiments. In the medical research field, the pandemic has provided advancements in medical science that would not have been possible without access to a living laboratory. However, the advancement in knowledge related to the pandemic may have been further accelerated if the local and international communities and policy makers were united in their administrative approach. By linking the medical and social sciences, through the distinct prism of trust, the article contributes to reflections upon the COVID-19 pandemic.

The article engages in a transnational and transdisciplinary exercise in reflexivity around the theme of trust and COVID-19. This scoping article is centered on the question of whether the COVID-19 pandemic represents, inter alia, a crisis of trust, one theme that successfully travels between the social and medical sciences. The article does not attempt to process trace public policy in relation to COVID-19 as a result of public policy. Any attempt to do so, would be extremely complicated to achieve. Process-tracing involving study-based empirical analysis might allow inferences in relation to a specific country case; but could not easily be replicated. Mapping statistical indicators in a comparative sense lies beyond the scope of this article. As (

Cole and Stivas 2020) have demonstrated (

Table 1), trust is deeply contextual. Interpretation is the best way forward, in the context where outcomes cannot be known. Outputs, on the other hand, can be interpreted.

Meijer et al. (

2018), for example, provide an interpretative framework to guide and structure assessments of government transparency. Moreover, the imposing body of literature that has been published on trust and transparency is targeted at processes and possibly outputs.

Lægreid and Rykkja (

2019) connect successful crisis management with the citizens’ behavior that is based on trust in government and on government capacity.

Boin et al. (

2017) suggest that to assess the crisis response, one must, among others, ask how prepared the authorities were, and how they made sense of the crisis and communicated with citizens. The article maps out common understandings of trust across disciplinary boundaries and discusses how these might be applied to cognitive fields in the medical and social sciences.

Building on the diagnosis of a crisis of trust in the field of health security and governance (

Downs and Larson 2007;

Hilyard et al. 2010;

Lo Yuk-ping and Thomas 2010), the article renews with calls to restore trust (thereby improving understandings of the challenges raised by COVID-19) by enhancing transparency. Section One introduces a brief review of the core dimensions of trust and COVID-19, while section two develops a multi-layered, transnational and transdisciplinary inquiry. In the final section, the authors provide pointers for how to rebuild trust by restoring an optimum trust balance.

2. A Question of Trust

Trust has long been identified as an essential component of social, economic and political life (

Cook 2001;

Rothstein 2005). Earle and Siegrist identify trust as the willingness to make oneself vulnerable to another based on a judgement of similarity of intentions or values (2008). The wider trust literature has identified a range of potential factors underpinning trust, such as citizen satisfaction with policy, economic performance, the prevalence of political scandals and corruption and the influence of social capital.

Parker et al. (

2014, p. 87) sum up the underlying assumption in much of the literature that ‘the public is more trusting when they are satisfied with policy outcomes, the economy is booming, citizens are pleased with incumbents and institutions, political scandals are nonexistent, crime is low, a war is popular, the country is threatened, and social capital is high.’ There is also a frequent link with mistrust, though the latter phenomenon also has its own distinct literature (

Avery 2009;

Davis 1976;

Fraser 1970;

Sztompka 2006). Health scandals, such as mad cow disease in the UK or the tainted blood scandal in France, have a particular place in the interface between citizens and their trust in politics and the health and related professions (

Lanska 1998). In the current literature, trust is treated as one of the main determinants of citizens’ compliance and collaboration with the governmental measures during a pandemic (

Balog-Way and McComas 2020;

Rowe and Calnan 2006;

Slovic 1999). Considering trust and the COVID-19 pandemic,

Fetzer et al. (

2020) associated the high levels of trust in government with the low levels of stress and misperceptions. They concluded that high levels of trust generated higher degrees of compliance with the governmental measures. Similar were the findings of

Oksanen et al. (

2020) who studied the relationship between trust and compliance in various countries of Europe.

There are powerful causal narratives around the loss of trust in contemporary societies. Four types of explanation are typically provided for the loss of trust (

Devine et al. 2020;

IPSOS 2020;

Martin et al. 2020;

Seyd 2020). Is the loss of trust a consequence of poor performance (after a decade of sluggish economic growth and inability to recover from the financial crisis of 2008–09) (

van der Meer and Hakhverdian 2017)? Or is it the result of a disconnect and distance between government and citizens, with the former unable to accommodate the preferences of the latter (

Fledderus et al. 2014;

Fisher et al. 2010;

Hardin 2002)? Or does it result from a general belief that politicians in general are corrupt and self-serving (

Grimmelikhuijsen 2012;

Park and Blenkinsopp 2011)? Or, indeed, is it the consequence of a lack of transparency and accountability? These four dimensions—trust and performance, trust and disconnect, trust and honesty or benevolence, trust and transparency—are each pertinent as forms of bridging research agendas. These precise linkages are explored here in terms of the health and security crisis represented by COVID-19.

Trust and performance: Is trust a consequence of ‘output legitimacy’ whereby users reward or punish service providers on account of results? In many countries, there has been a diffusion of new public management-type solutions in health care, whereby services are evaluated on the basis of key performance indicators such as the number of operations delivered or beds occupied. A holistic view of healthcare has, arguably, suffered (

Kruk and Freedman 2008;

Veillard et al. 2005). Financial resources (30–35% of budgets) invested in medical care have been diverted into human resources involved in a myriad of administrative tasks (

Shrank et al. 2019). The narrative of performance runs counter to the absolute belief in healthcare. Part of the problem is one of process: how effectively are resources devoted to frontline services? Hence, in France there is controversy over organizations such as the regional health agencies, run by technocrats rather than professionals, on the basis of ‘managerial’ performance indicator regimes. While this can be interpreted in terms of corporate defense on behalf of the medical profession, it is also the case that narrow key performance indicators do not lend themselves to more holistic risk management strategies. There were controversies in several countries, at the height of the pandemic, over the lack of medical supplies because of outsourcing and the negative consequences of management by objectives (allegedly reducing the number of beds available for COVID-19 emergency patients). Such disputes did little to reduce mistrust between governments and citizens.

Trust and disconnect: The pandemic has revealed how administrative complexity can be an independent factor of mistrust. Who does what is a vital question in terms of basic transparency. Competition between bureaus can have a debilitating effect in terms of access to public services, especially during a period of pandemic. In the case of France, for example, how to obtain masks, gloves, sprays, or simply to undertake a test involved intense interagency (regional health agency, prefectures) and intergovernmental (the state against the regions) competition. Similar stories emerged elsewhere, not least between the central government and the devolved administrations in the UK or the central government and the autonomous communities in Spain. This issue is not a simple one of distinction between types of polity, for example federal versus unitary systems: while the US and Brazilian federations descended into partisan-based rivalries between states, federal Germany initially demonstrated one of the most joined-up responses to the pandemic.

Trust and honesty or benevolence: Health professionals have been in the forefront of the fight against COVID-19, but they are not always free to tell the truth. Scientific communities themselves are divided, adding to the contested status of scientific truth. From the perspective of medical practitioners, questions of distributive justice (

Huxtable 2020)—about the allocation of resources and the determination of which patients should receive treatment—are paramount, yet difficult to assume politically, hence the link to questions of transparency.

Trust and transparency: The presupposition that transparency produces better outcomes underpins much contemporary policy. Transparency might also be framed in terms of building confidence via accountability and participation and enhancing trust on account of fairness and open procedures.

Heald (

2013) outlines four directions of transparency: vertical transparency (where a person or an organization has hierarchical oversight over another person or organization), upwards transparency (when the superior can observe the subordinate), downwards transparency (where the rulers are accountable to the ruled), and horizontal transparency (further elaborated by

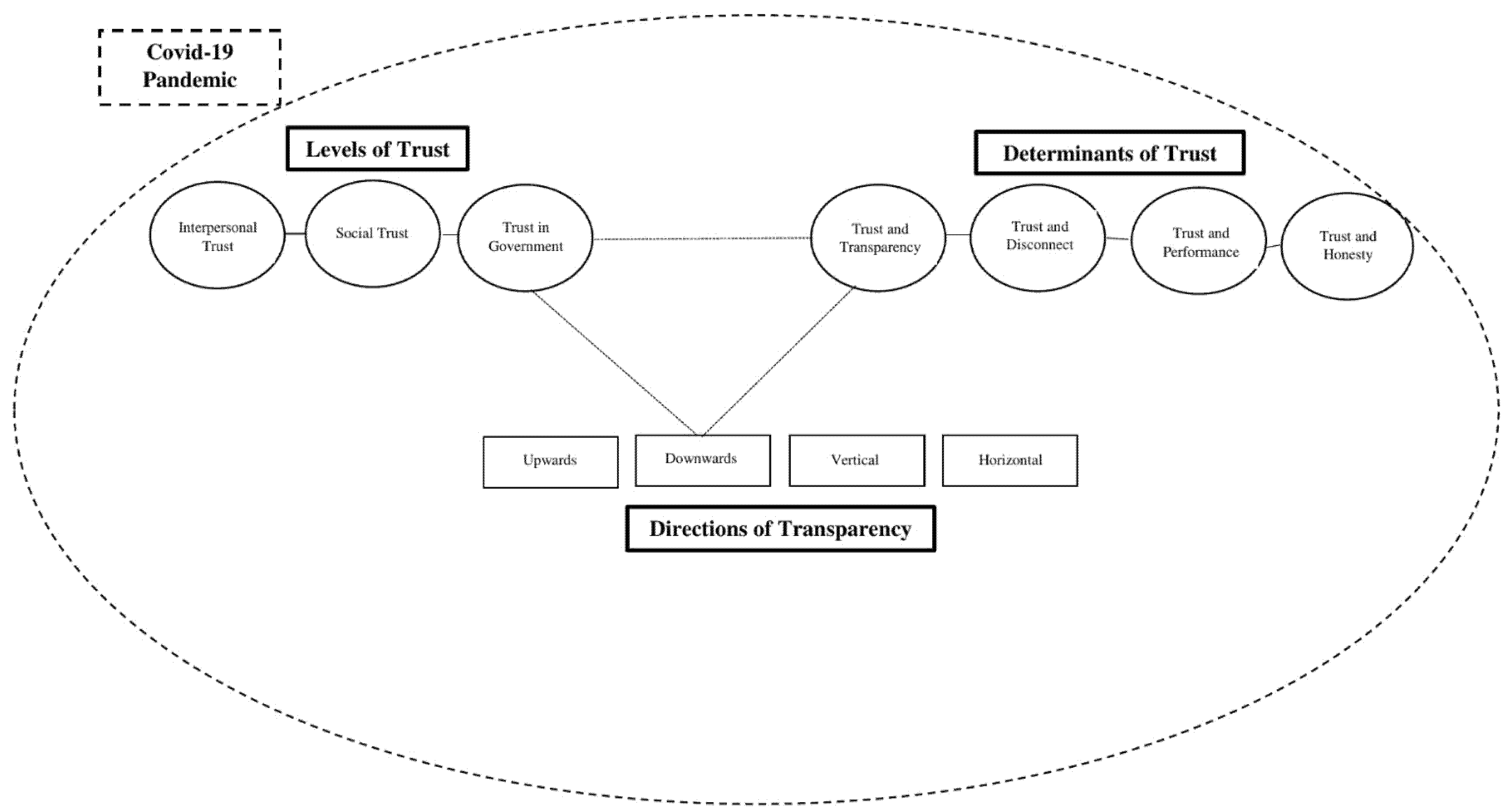

Grimmelikhuijsen 2012, p. 563) as ‘the availability of information about an organization’). Unpicking Heald’s model, and applying its approach to COVID-19, there are variable linkages to trust and transparency across time and space. Vertical transparency and upwards transparency can be combined. They appear as a modern equivalent of Bentham’s panopticon, where the central guardians (of a prison, of the state) can observe and thereby control all activities of subordinates. Such data-intensive and intrusive mechanisms have come to the fore during the COVID-19 crisis, as governments have resorted to extraordinary measures to ‘securitize’ the pandemic. Such measures are possibly efficient and probably necessary, especially when physical movement needs to be limited. Such methods have not been limited to authoritarian regimes, but they have spilled over into more general use in Western democracies (worn down by the past decade of terrorist attacks). Blurred processes, emergency procedures and a constitutional decision-making circuit have scarcely ensured clear information about how crisis decisions were reached during the pandemic. They have fallen down against the standard of trust as honesty and diminished the bases of freedom. They are unlikely to build trust. In Hong Kong, for instance, despite the local government’s attempts to persuade the public that its dealings with the pandemic are transparent (the government explicitly emphasized transparency in official statements, activated COVID-19-relevant information proxies, and conducted daily press conferences), the trust in Hong Kong government is amongst the lowest globally. How the different ‘directions’ of transparency intervene with the ‘levels’ and ‘determinants’ of trust is illustrated in

Figure 1. We assume that transparency can influence trust mostly at the ‘trust in government’ level of trust and therefore, in a downwards direction of transparency. To support our arguments, we build on the most up-to-date literature on COVID-19. We substantiate our claims with evidence from various administrations and we highlight notable events from each administration’s struggle to control the pandemic.

Throughout the article, we make the point that trust as performance, connection, benevolence and transparency is most effective when these facets are combined. Specifically, we do not rank these values or prioritize transparency. We focus more on transparency, however, in part because of content and word limitations, in part because of the growing couplings of the two concepts (

Cucciniello et al. 2017) but mainly because it is the best one for distinguishing between national responses.

3. Trust, COVID-19 and Transdisciplinary Enquiry

The social scientist is bound to defer in some respects to the medical sciences, but each has an interest in conceptualizing the role of trust and mistrust during health crises. The agendas are genuinely transdisciplinary. There has been mass mobilization: from governments, research agencies, big pharmaceutical firms, professional bodies, the medical, scientific and artificial intelligence communities, all in search of problem solutions and understanding. No interest has been left unaffected, be it in international organizations (the World Health Organization, the European Union), powerful nations (United States, China), multinational firms, the professions, civil society and individuals.

The pandemic demonstrates the contested nature of medical knowledge: as testified by the early controversies over hydroxychloroquine, through the race for a vaccine, or contrasting containment strategies (herd immunity against lockdown and, more recently, zero-cases against endemic virus approaches). Scientists have replaced politicians as regular guests of radio and 24 h television programs. However, the crisis also illustrates the barriers to the functioning of a global medical epistemic community, free to exchange in the interests of scientific discovery.

The article interrogates one dimension of the health crisis: namely, the role of trust. Trust is one of the most contested concepts within academic research. The

OECD (

2017, p. 3) has argued that ‘governments cannot function effectively without the trust of citizens, nor can they successfully carry out public policies, notably more ambitious reform agendas.’ Elsewhere we have defined trust in terms of human-like constructs such as relationships (interpersonal, intermediate, institutional), properties (benevolence, honesty, ability, trustworthiness), levels (interpersonal, social, institutional, international), types (confidential, community), in relation to associated concepts (resilience, risk, confidence, transparency), and in terms of public policy and processes (

Stafford et al. 2022). For current purposes, trust needs to be understood as a generic term to describe dynamics taking place at different levels of analysis: interpersonal, social and collective. The trust literature allows a fairly precise operationalization, especially relating to the three levels of trust of

Zmerli and Newton (

2011), which can be adapted to the COVID-19 crisis. Medical and social science rely on theorizing at three main levels of analysis: individual, intermediate and institutional. Each type of analysis carries a distinctive contribution and the stakes of each are high, including psychological wellbeing, a civil society and trust in government.

Interpersonal trust:

Rousseau et al. (

1998, p. 395) define trust as ‘a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another’. It involves an interpersonal relationship, with at least two players, as in a clinical–patient relationship. In terms of both trust and confidence, the individual level is key, because individual perceptions of risk are germane to the adoption of preventive measures (

Khosravi 2020). Citing studies of various countries,

Siegrist and Zingg (

2014, p. 25) suggest that ‘trust had a positive impact on adopting precautionary behavior during a pandemic’. In another close formulation ‘particular social trust’ involves those known to us personally, such as family, friends or work colleagues. A breakdown of trust shatters this psychological equilibrium. Cross-national evidence from lockdowns and quarantines illuminates the challenged state of psychological well-being of individuals, especially in terms of their primary networks (friends, family) and practices (as a result of social distancing). Even within these tight personal networks, evidence from scholars working on psychological indicators points to an increase in indicators of social tension, such as divorce, gender violence and isolation as a result of the COVID-19 crisis (

Boserup et al. 2020). Increases in social violence and violation by communities in relation to social distancing measures are major concerns in relation to public perceptions and information provided by respective governments and their representatives. Misinformation and lack of action in the early stages by governments led to an apathetical approach by communities and a feeling of identity immunity that proved costly as the pandemic wore on.

Such tensions are also apparent in the medical/clinical domain. Adapted to medical ethics, for example, practitioner and client relationships span elements of interpersonal and intermediate trust. The appropriate relationship is prescribed and described in medical ethics (with trust as a form of confidential relationship, absolutely secretive, in no senses negotiated with a third party) and regulated by strict professional and ethical standards. Here, the medical relationship is stronger than even the tightest form of inter-personal political relationship. COVID-19 challenges interpersonal (medical) trust in a novel manner; traditional consultative practices are changing (with the rise of eMedecine), while the competition for scarce resources has ensured that COVID-19 has eclipsed more traditional treatments (for example, the postponing of cancer operations).

Recent literature in the field of pediatrics has also raised issues of trust between medical practitioners, children and parents and raised the question of the appropriate level of analysis. At the individual level of analysis, trust is essential to the clinical–family relationship. Trust constitutes more than an intentional action; it involves a confidential relationship. Trusting relationships can produce ‘confidence, peace of mind and security, while broken trust breeds stress, game playing and anxiety’ (

Sisk and Baker 2019, p. 1). The central paradox, in the relationship between pediatricians and children, is that trusting relationships are mediated by third parties, by parents. There is an enormous leap from the individual-level, through socially mediated forms of trust and onto the headline events such as a crisis of trust in the US health system.

Sisk and Baker (

2019) identify a deeply embedded crisis in doctors and the US health care system as a whole over the last half century, a finding that could be exported to many other countries.

The key analytical point is that, in the medical sphere as in the political one, discussion centers on the linkages between individual, intermediary and organizational levels of analysis. The COVID-19 pandemic has focused attention on the need to strengthen the links between patients, health care teams and organizations. From the relevant literature, we learn that the most effective responses in a pandemic are joined up ones, where individuals (responsible for following guidelines) trust intermediaries (health professionals) and are receptive to messages (nudges) from the relevant governmental authorities. Hence, the distinction between hard medical and soft social science blurs when patients/citizens are required to be active participants in combatting the virus. The two worlds are linked by the questions of trust.

Social or collective trust: ‘General social trust’ is that placed in ‘unknown others’. This form of trust performs a key function in modern societies, as

Newton (

2007, p. 349) notes, because ‘much social interaction is between people who neither know one another nor share a common social background.’ Generalized social trust or ‘thin trust’ is centered on more general information about social groups and situations (

Keele 2007). In relation to COVID-19, the ability to empathize with members of an imagined community (region, nation, even continent) is a core element of community integration. Health professionals—frontline workers, such as nurses—are everywhere a source of national pride and mobilization, yet they are also amongst the individuals the most in danger of contracting the virus. How civil society has reacted to the pandemic is a matter of empirical investigation. Social capital is literally excluded, as a result of lockdown and travel restrictions. Society has not collapsed. Even where confinement was harsh, as in Italy, Spain and France, the strength of civil ties allowed the crisis to be weathered. Public participation is central to the success of adopting preventive measures.

There has been a dangerous ebbing of social trust in many countries where the utility of wearing masks was questioned and, above all, where vaccination has been actively contested and resisted. Hence a society’s response to the pandemic depends on the levels of trust—trust in civil society, trust in health professionals and trust in the government—and the interactions between these variables. The case of Hong Kong is interesting in this respect. Though the Hong Kong SAR Government was very transparent in providing data about its handling of the virus, it enjoyed relatively low levels of public trust. Nonetheless, the city is widely considered as having been effective in containing the virus. The numbers of COVID-19 infections and deaths are amongst the lowest in the world while, for the duration of the pandemic, Hong Kong never resorted to imposing any severe intracommunity restrictive measures. Hong Kong’s successful approach can be traced to the high level of trust in civil society and interpersonal trust among its citizens. Here, there is a slightly paradoxical situation where the trust in the government is not very high, but people are behaving in a way that is cooperative towards the government’s measures to curb the spread of the virus (

Chan 2021). Hong Kong society showed itself to be disciplined and coherent, as Hong Kongers swiftly adopted mask-wearing in public to illustrate their collective reaction to COVID-19. Mask-wearing was among the risk management measures proposed by the government of Hong Kong. Stronger trust in the risk management authority can facilitate cooperation (

Chan 2021;

Groeniger et al. 2021;

Rieger and Wang 2021). In Hong Kong, despite the low levels of trust to the government, the citizens complied with the mask-wearing rules. This capacity of the community has kept Hong Kong largely unaffected by the pandemic. It is also noteworthy that a high level of trust in health professionals is recorded in Hong Kong (

Smith 2020), making it a key determinant of how well Hong Kong contains COVID-19. The general public’s response contributed to Hong Kong’s low number of COVID-19 cases and deaths.

Trust in government: our third dimension, has performed a major role during the pandemic by affecting the public’s judgements about risks and related benefits (

Khosravi 2020). From a psychological perspective,

Bish and Michie (

2010) argue that trust in government is a key variable affecting individual behavior faced with pandemics; the more consistent the message, the more likely it is to influence behavior.

Zmerli and Newton (

2011, p. 3) define political trust as a ‘very thin form of trust’ characterized by a ‘kind of general expectation that on the whole, political leaders will act according to the rules of the game’. The arguments about the role of trust in the current literature are divided. Some researchers argue that at the beginning of the pandemic and in certain jurisdictions, trust in government was increased (

Bol et al. 2021;

Groeniger et al. 2021;

Rieger and Wang 2021;

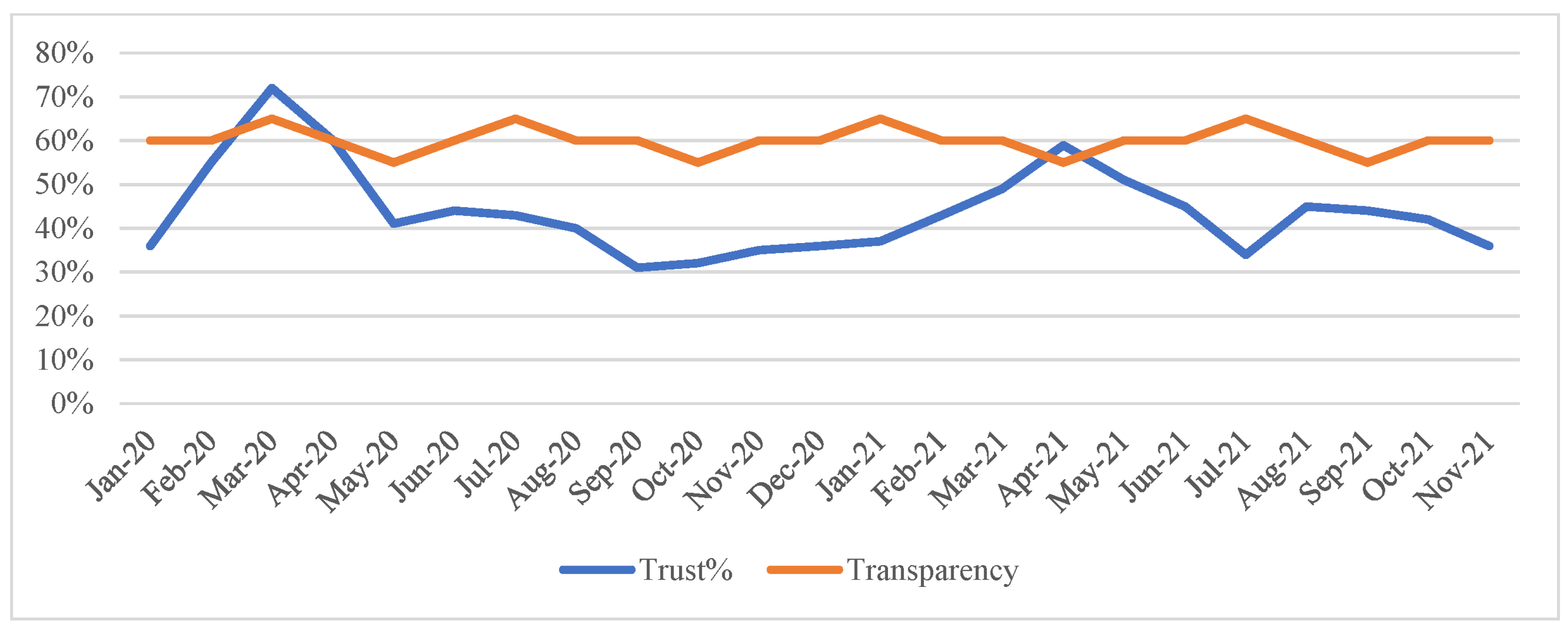

Sibley et al. 2020). Conversely, indexes of political trust (e.g., the Edelman Trust Barometer (

Edelman 2021)) suggest a general decline across liberal democracies in the past decade, even before the COVID-19 crisis. The evidence points to variable dosages of mistrust in different democratic countries, with a typical trust cycle (rallying to the executive, followed by deep unpopularity) being observed as during other pandemics (

van der Weerd et al. 2011). Of more importance is the challenge to fundamental liberal-democratic values occasioned by the pandemic. Political anthropologists identify as ‘tricksters’ characters intent on subverting the system that brought them to power (

Horvath et al. 2020). More than one leader has attempted to make ‘good use of a crisis’, to drive through contested political changes (the case of Hungary’s premier Victor Orban being the obvious one). Even when the transgression of democracy has been less explicit, there are fears of a hollowing out of civil society and a weakening of civil liberties, via tracing applications such as

Tous anti-covid in France or

LeaveHomeSafe in Hong Kong.

4. Rebuilding Trust by Restoring an Optimum Trust Balance

Often trust is mistakenly presented as confidence and confidence as trust. In their ‘Trust, Confidence and Cooperation’ model,

Earle and Siegrist (

2008) distinguish between trust and confidence. Trust is defined as the willingness to make oneself vulnerable to another based on a judgement of similarity of intentions or values. Confidence is defined as the belief based on past experience or evidence that certain events will occur as expected. Both trust and confidence influence people’s willingness to cooperate. Binding trust and confidence imply the need for consistent messages from central government, along with authoritative steering from intermediaries such as the health and medical professions. The prospects for such convergence are improved where, as in Hong Kong, there was recent experience of a pandemic and behavior adapted accordingly.

Zhu (

2020), for example, stressed the importance of the experience that the population of Hong Kong gained with fighting SARS in 2003.

Trust in government is important; even more central is trust and confidence in advisors/experts (

Lavazza and Farina 2020). During pandemics, most people are not in a position to evaluate the information about the risks and benefits associated with vaccination. Therefore, they rely on experts, especially on those experts they trust, who are once removed from government. This finding was backed by

van der Weerd et al. (

2011) in their study of the H1N1 flu pandemic in the Netherlands: most of the respondents wanted the information about infection prevention to come from the municipal health services, health care providers and the media, rather than central government. In some cases (i.e., Hong Kong SAR and Taiwan) experts are mobilized to strengthen the trust in institutions. In other instances, the medical experts are sidelined, or even silenced, by the governmental officials (see the case of the whistle-blowing doctor, Li Wenliang, at the onset of the pandemic in China). It is also possible that the trust between politicians and experts breaks down as it happened with the UK Sage committee, or with the central scientific committee in France. When such conflicts occur, political will prevails. In sum, governments of all persuasions seek the maximum utility from medical experts. However, there can be a tipping point in the relationship between politicians and experts, especially when the experts appear to contradict the government (e.g., the conflict between former US president Trump and Anthony Fauci).

In terms of trust, individual responses and reactions, social mediation and governmental responses need to complement each other. Trust processes are different at each of these levels, but the literature points to their mutually reinforcing character (

Anderson 1998;

Diez Medrano 1995). In a pandemic, governments need to persuade individuals to adapt their behaviors, and such persuasion will be all the more convincing in that it is nested in social networks. Here, reverting to the advice of psychologists and medical scientists assumes its own coherence. Bringing into coherence the three levels of analysis is the best means for ensuring the diffusion of legible, clear messages, with the potential to build trust based on confidence (

Siegrist and Zingg 2014).

The adjectival qualities of trust—performance, connection, benevolence, transparency—are also most effective when combined. Performance is best understood in discursive terms as performativity; coherent speech acts underpinned by consistent reasoning are the best shaped to be able to persuade and make citizens susceptible to nudge. The messages coming from the top need to be consistent within their own terms of reference; far from the governmental cacophony observed in France or the US, or—even worse—the transgressive behavior of advisors in UK. Double standards have a detrimental effect on honesty, hence affect perceptions of benevolence, feed disconnection and political distancing from the people. Blurred and contradictory messages by political leaders and their entourages during the COVID-19 crisis ran counter to the advice of medical practitioners, whereby transparency in terms of access to decisions and to information is the best way of influencing behavior during a pandemic and restoring trust (

van der Weerd et al. 2011). Similar conclusions might be deduced from the work view of the transparency optimists working in the field of political science.

Grimmelikhuijsen (

2012) has shown in an experiment that, while citizens will use performance information to make rational and conscious decisions, the positive effect of transparency on trust is also partly due to an emotional factor related to the act of transparency as such. That government appears to be transparent is in itself a factor of the perceived competence component of trust. Hence, governments need to provide accessible information, while avoiding information overload (

van de Walle and Roberts 2008). Clear consistent ethical guidelines are called for by the medical community (

Huxtable 2020).

Clear and consistent legitimizing discourses are, almost by definition, most difficult to sustain in a crisis, the political equivalent of Schumpeter’s creative destruction. For governments to be consistent in their discourses and actions during a pandemic is not an easy task. In times of crisis, governments assume certain risks. Sometimes they risk to undertake measures that can cause thousands of COVID-19 related deaths in order to spare their administration’s economy. Conversely, sometimes, the authorities risk devastating the economic life of their countries by imposing severe and lengthy lockdowns in order to safeguard as many lives as possible (

Bol et al. 2021). In other instances, policymakers assume the risk of serving the interests of particular interest groups at the expense of others. Risk assumption is inherent in crises. Risk assumption affects the capability of policymakers to be consistent not only in their rhetoric, but also in their actions.

How can trust in public policy making be established or restored? Many recent examples show how easy it is to lose in public policy making, as the cases of financial policy, pension policy, environmental policy and many other examples demonstrate. Already on shallow foundations, the COVID-19 crisis demonstrated stark national variations between countries. Which factors be identified that support the production of trust? Transparency, as a major phenomenon in its own right (

Cucciniello et al. 2017), emerges from recent literature as one of the key factors for the production of trust (

Stafford 2017). Regular calls for transparency heard during scandals, where trust is lost, aim at restoring trust and are a case in point. While trust is essential for controlling the virus in an immediate sense, transparency and openness of information is necessary for a longer-term policy response that is resilient and sustainable. The research suggested that maintaining transparency of administrative data is the best way to influence behavior during a pandemic and restore trust. The messages coming from the top need to be clear and consistent. Is transparency thus the principal mechanism for restoring trust? It is not that straightforward. In fact, the case of COVID-19 illustrates a trust-transparency paradox, whereby trust requires transparency (witness the reaction to early attempts to deny the virus and control information), but transparency can undermine trust (insofar as it focuses attention on the malfunctioning of liberal democracies and their uneven management of the crisis). In

Figure 2, we build on the trust-transparency matrix of

Stafford et al. (

2022) to demonstrate the complex relationship between trust and transparency. In China mainland, the surveys reveal that almost the total of the citizenry trust their government (

Edelman 2021). At the same time, the openness of the government is limited, if non-existent. We call

Blind Faith this mix of high trust with low transparency that we observe in China. The Taiwanese government also enjoyed high levels of political trust during the pandemic. However, the authorities of the Pacific island were much more transparent than the authorities in mainland China about their dealings with the pandemic. High trust and high transparency, like in Taiwan, resulted in a

Synergy between the authorities and the public. Conversely, a combination of low trust and high transparency, as observed in Hong Kong, could result in negligible effects during a pandemic. As aforementioned, although the citizens of Hong Kong distrust their arguably transparent government, the coastal city has effectively controlled COVID-19. We name this situation:

Negligible Effects. Lastly, a situation of low trust and medium to low transparency, as in the U.K., generates a

Dual Dysfunctionality.

1 The above cases indicate that neither trust nor transparency are absolute preconditions of effective policymaking. There are more general paradoxes of transparency and trust: healthcare workers are the most trusted, for example, and the media least. Yet, in the era of 24-hour media coverage, strengthened by confinement, the media is the main source of information and performs a key transparency role in liberal democracies.

Unlike trust, the dimensions of transparency do not all push in the same direction. Vertical and upwards transparency are particularly suited to authoritarian regimes, or to executive-led decision-making processes (relying on emergency procedures and unaccountable uses of technology) in democratic regimes. Such regimes, turned inwards, are unlikely to embrace transparency beyond a form of social and political control: hence, the unwillingness to consent to the requirement to combat a global pandemic, to engage in policy transfer, to trust a global commons or to accept international standards, akin to international accounting norms. This lack of transparency feeds international mistrust: the pandemic demonstrated widespread skepticism of the validity of statistics across nations, for example. The trust-transparency linkage makes most sense in the context of downwards and horizontal transparency. Restoring global norm-based governance requires commitment to the most positive elements of the transparency agenda, in terms of agreed international standards (for example, over health statistics), engagement with existing international organizations (especially the World Health Organization) and drawing the most robust knowledge from transdisciplinary scientific approaches. Global norms are more important than ever. International health crises require efforts to rebuild trust, understood in a multidisciplinary sense as a relationship based on trusteeship, in the sense of mutual obligations in a global commons, where trust is a key public good.