Evaluating the Unconventional Monetary Policy of the Bank of Japan: A DSGE Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Model

Assets are assumed to be imperfect substitutes for each other in wealth-owners’ portfolios. That is, an increase in the rate of return on any one asset leads to an increase in the fraction of wealth held in that asset, and to a decrease or at most no change in the fraction held in every other asset.

2.1. Household

2.2. Firm

2.3. Fiscal and Monetary Authorities

2.4. Analysis of Portfolio Rebalancing Mechanism

3. Calibration

3.1. Calibration

4. Results

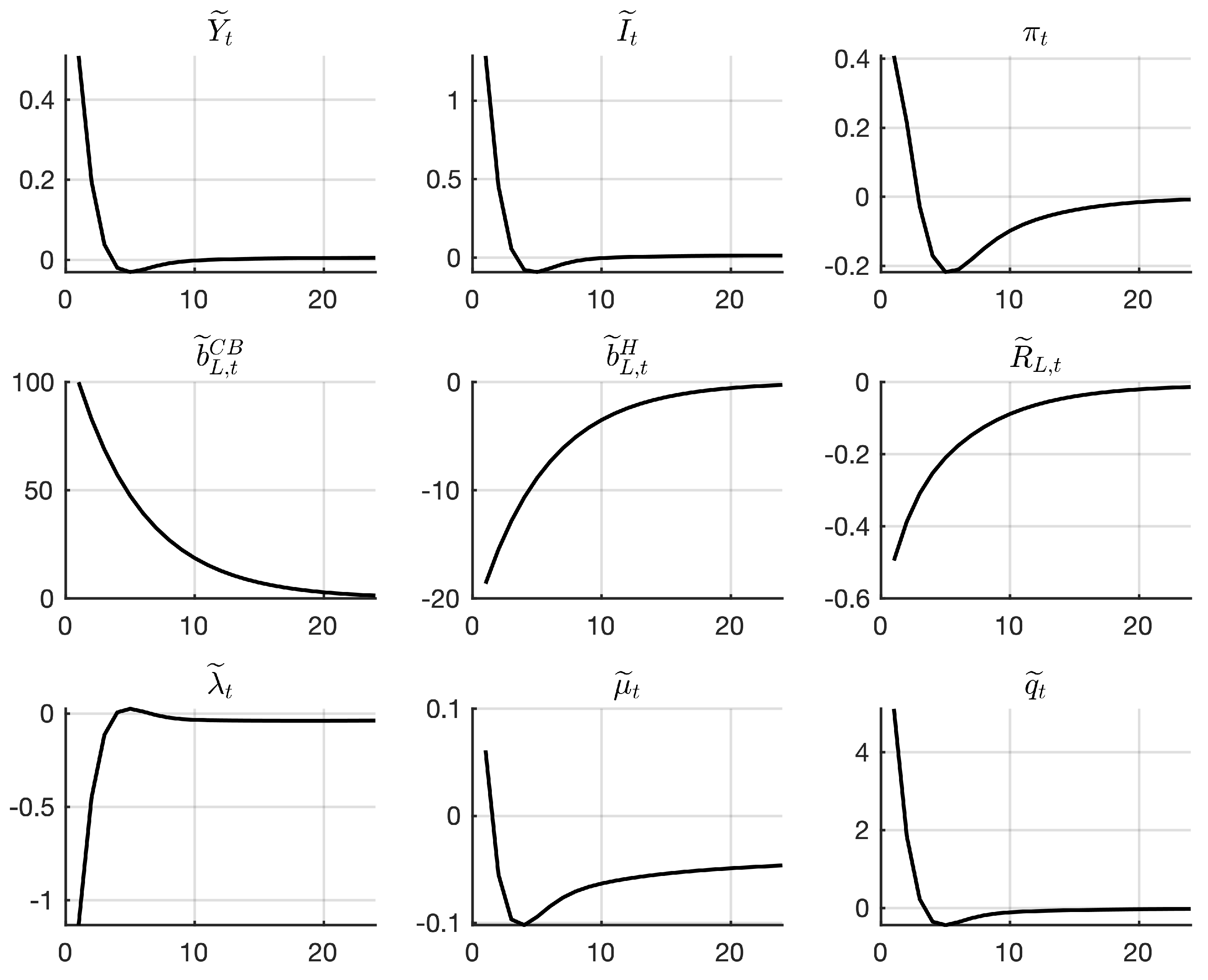

4.1. Baseline Simulation

4.2. QE Sensitivity Analysis

5. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Steady State

Appendix B. The Log-Linearized Model

| 1. | Reith (2011) provided a good a comparison of QE in Japan and the US. Gupta and Marfatia (2018), and Gupta et al. (2019) also took the event-study approach to study the impact of unconventional monetary policy on stock markets. |

| 2. | Siranova and Kotlebova (2018) used a structural vector autoregression (SVAR) model to check ECB monetary-policy effects via the banking sector in Slovenia. Caraiani et al. (2020), and Huber and Punzi (2020) discussed the wealth channel of unconventional monetary policy. Caraiani et al. (2020) used a quantile structural vector autoregressive (QSVAR) model to analyze whether the impact of monetary-policy shocks on real housing returns in the United States was contingent on the initial state of housing-market sentiment. |

| 3. | For related studies, please refer to Olmo and Sanso-Navarro (2018), Kiss and Balog (2018), Chebbi and Derbali (2019). |

| 4. | For related studies, please refer to Harrison (2011, 2012), Falagiarda (2014), Cova et al. (2015), Del Negro et al. (2017), McKay et al. (2016) and Priftis and Vogel (2016, 2017). |

| 5. | Socci et al. (2018) used the calibrated dynamic computable general equilibrium (DCGE) model of the Italian economy to check the effects of the unconventional monetary policy of ECB. |

| 6. | This paper was written in 2015, and the conclusion is based on the situation of the Japanese economy in that time. |

| 7. | Indexation of each household is omitted because they are homogenous and identical. |

| 8. | This kind of classification in also used in model calibration, the steady state ratio of two kinds of bonds with different maturities relative to the total amount of government bonds. |

| 9. | means the long-term bonds held by households. |

| 10. | BoJ also purchases risky assets such as ETFs and J-REITs from the private sector, but the quantity of these purchases is much less than the purchased quantity of Japanese government bonds is. |

| 11. | |

| 12. | This is not true for a real economy because other financial institutions can hold government debt. In this model, financial intermediaries are neglected, and all private-sector households hold the remaining long-term bonds. |

| 13. | See Appendix B for log-linearization of the model. |

| 14. | See Appendix A. |

| 15. | Short-term debt includes bonds held by the central bank as the operation instrument in the interbank market plus bonds with maturity less than or equal to 1 year. |

| 16. | Long-term debt is calculated by subtracting its amount from total debt. |

| 17. | Data of Japanese government bonds can be obtained from http://www.mof.go.jp/jgbs/reference/appendix/index.htm accessed on 1 May 2021. |

| 18. | For other steady state values, see Appendix A. |

| 19. | The steady state of labor supply is calculated by assuming that the share of representative household’s time endowment spent on labor supply is equal to 0.3. |

| 20. | In similar research, this parameter was set to different values such as Chen et al. (2012) (0.015), Andres et al. (0.045), Harrison (2011, 2012) (0.1, 0.09). Following Falagiarda (2014), was set to 0.01, which means that 1% of household’s income is paid for the portfolio adjustment cost. Sensitivity analysis in the next section checks the role of this parameter in the portfolio-rebalancing channel of QE. |

| 21. | is derived from the steady state of the first-order conditions Equations (9) and (10). See Appendix A. |

| 22. | This calibration was conducted by checking the impulse response of through trial and error. Just like parameter , and were also assumed to be important in the portfolio-rebalancing channel of QE. Sensitivity analysis is given in the next section. |

References

- Andres, Javier, J. David López-Salido, and Edward Nelson. 2004. Tobin’s Imperfect Asset Substitution in Optimizing General Equilibrium. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 36: 665–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Angrick, Stefan, and Naoko Nemoto. 2017. Central Banking Below Zero: The Implementation of Negative Interest Rates in Europe and Japan. Asia Europe Journal 15: 417–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernanke, Ben, Vincent Reinhart, and Brian Sack. 2004. Monetary Policy Alternatives at The Zero Bound: An Empirical Assessment. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2: 1–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calvo, Guillermo A. 1983. Staggered Prices in A Utility-Maximizing Framework. Journal of Monetary Economics 12: 383–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraiani, Petre, Gupta Rangan, Lau Chi Keung Marco, and Hardik A. Marfatia. 2020. Effects of Conventional and Unconventional Monetary Policy Shocks on Housing Prices in the United States: The Role of Sentiment. Journal of Behavioral Finance. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebbi, Tarek, and Abdelkader Derbali. 2019. US Monetary Policy Surprises Transmission to European Stock Markets. International Journal of Monetary Economics and Finance 12: 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Han, Cúrdia Vasco, and Ferrero Andrea. 2012. The Macroeconomic Effects of Large-Scale Asset Purchase Programmes. The Economic Journal 122: F289–F315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cova, Pietro, Pagano Patrizio, and Pisani Massimiliano. 2015. Domestic and International Macroeconomic Effects of the Eurosystem Expanded Asset Purchase Programme. Economic Working Papers No. 1036. Rome: Bank of Italy, Economic Research and International Relations Area. [Google Scholar]

- Vasco, Curdia, and Woodford Michael. 2011. The Central-Bank Balance Sheet as An Instrument of Monetary Policy. Journal of Monetary Economics 58: 54–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Negro, Marco, Eggertsson Gauti, Ferrero Andrea, and Kiyotaki Nobuhiro. 2017. The Great Escape? A Quantitative Evaluation of The Fed’s Liquidity Facilities. American Economic Review 107: 824–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eggertsson, Gauti B., and Woodford Michael. 2004. Optimal Monetary and Fiscal Policy in a Liquidity Trap. NBER Working Papers No. 10840. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Falagiarda, Matteo. 2014. Evaluating Quantitative Easing: A DSGE Approach. International Journal of Monetary Economics and Finance 7: 302–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Falagiarda, Matteo, and Massimiliano Marzo. 2012. A DSGE Model with Endogenous Term Structure. Working Papers wp830. Bologna: Universita’ di Bologna. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, Shin-ichi. 2018. Impacts of Japan’s Negative Interest Rate Policy on Asian Financial Markets. Pacific Economic Review 23: 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galí, Jordi. 2015. Monetary Policy, Inflation and The Business Cycle: An Introduction to The New Keynesian Framework and Its Applications. Jersey: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gertler, Mark, and Peter Karadi. 2011. A Model of Unconventional Monetary Policy. Journal of Monetary Economics 58: 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertler, Mark, and Peter Karadi. 2013. QE 1 vs. 2 vs. 3...: A Framework for Analyzing Large-Scale Asset Purchases as A Monetary Policy Tool. International Journal of Central Banking 9: 5–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gertler, Mark, and Nobuhiro Kiyotaki. 2010. Financial Intermediation and Credit Policy in Business Cycle Analysis. In Handbook of Monetary Economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 3, pp. 547–99. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Rangan, and Hardik A. Marfatia. 2018. The Impact of Unconventional Monetary Policy Shocks in The US on Emerging Market REITs. Journal of Real Estate Literature 26: 175–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Rangan, Lau Chi Keng Marco, Liu Ruipeng, and Hardik A. Marfatia. 2019. Price Jumps in Developed Stock Markets: The Role of Monetary Policy Committee Meetings. Journal of Economics and Finance 43: 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrison, Richard. 2011. Asset Purchase Policies and Portfolio Balance Effects: A DSGE Analysis. In Interest Rates, Prices and Liquidity: Lessons from the Financial Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 117–43. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Richard. 2012. Asset Purchase Policy At The Effective Lower Bound for Interest Rates. Bank of England Working Papers 444. London: Bank of England. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Florian, and Maria Teresa Punzi. 2020. International Housing Markets, Unconventional Monetary Policy, and The Zero Lower Bound. Macroeconomic Dynamics 24: 774–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joyce, Michael, David Miles, Andrew Scott, and Dimitri Vayanos. 2012. Quantitative Easing and Unconventional Monetary Policy—An Introduction. The Economic Journal 122: F271–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kiyotaki, Nobuhiro, and John Moore. 2012. Liquidity, Business Cycles, and Monetary Policy. NBER Working Papers No. 17934. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, Gábor Dávid, and Enikő Balog. 2018. Conventional and Unconventional Balance Sheet Practices and Their Impact on Currency Stability. International Journal of Monetary Economics and Finance 11: 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippner, Leo. 2013. Measuring The Stance of Monetary Policy in Zero Lower Bound Environments. Economics Letters 118: 135–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krugman, Paul R., Kathryn M. Dominquez, and Rogoff Kenneth. 1998. It’s Baaack: Japan’s Slump and The Return of The Liquidity Trap. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1998: 137–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lars, Ljungqvist, and Thomas J. Sargent. 2012. Recursive Macroeconomic Theory, 3rd ed. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leeper, Eric M. 1991. Equilibria under “Active” and “Passive” Monetary and Fiscal Policies. Journal of Monetary Economics 27: 129–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, Alisdair, Nakamura Emi, and Steinsso Jón. 2016. The Power of Forward Guidance Revisited. American Economic Review 106: 3133–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meier, Andre. 2009. Panacea, Curse, or Nonevent? Unconventional Monetary Policy in The United Kingdom. Working Paper No. 09/163. Washington: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Olmo, Jose, and Marcos Sanso-Navarro. 2018. Unconventional Monetary Policies and The Credit Market. International Journal of Monetary Economics and Finance 11: 480–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Priftis, Romanos, and Lukas Vogel. 2016. The Portfolio Balance Mechanism and QE in The Euro Area. The Manchester School 84: 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priftis, Romanos, and Lukas Vogel. 2017. The Macroeconomic Effects of The ECB’s Evolving QE Programme: A Model-based Analysis. Open Economies Review 28: 823–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reith, Matthias. 2011. Unconventional Monetary Policy in Practice: A Comparison of “Quantitative Easing” in Japan and The USA. International Journal of Monetary Economics and Finance 4: 111–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siranova, Maria, and Jana Kotlebova. 2018. SVAR Description of ECB Monetary Policy Effects via Banking Sector in Individual EA Countries: Case of Slovenia. International Journal of Monetary Economics and Finance 11: 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socci, Claudio, Severini Francesca, Pretaroli Rosita, Ahmed Irfan, and Ciaschini Clio. 2018. Unconventional Monetary Policy Expansion: The Economic Impact through A Dynamic CGE Model. International Journal of Monetary Economics and Finance 11: 140–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, Lars E.O. 2003. Escaping from A Liquidity Trap and Deflation: The Foolproof Way and Others. Journal of Economic Perspectives 17: 145–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, John B. 1993. Discretion versus Policy Rules in Practice. In Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 39, pp. 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin, James. 1969. A General Equilibrium Approach to Monetary Theory. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 1: 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, James, and William C. Brainard. 1963. Financial Intermediaries and The Effectiveness of Monetary Controls. American Economic Review 53: 383–400. [Google Scholar]

- Ugai, Hiroshi. 2007. Effects of The Quantitative Easing Policy: A Survey of Empirical Analyses. Monetary and Economic Studies-Bank of Japan 25: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Vayanos, Dimitri, and Jean-Luc Vila. 2009. A Preferred-Habitat Model of The Term Structure of Interest Rates. NBER Working Papers No. 15487. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Rui. 2019a. Unconventional Monetary Policy in US: Empirical Evidence from Estimated Shadow Rate DSGE Model. International Journal of Monetary Economics and Finance 12: 361–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Rui. 2019b. Unconventional Monetary Policy in Japan: Empirical Evidence from Estimated Shadow Rate DSGE Model. Journal of International Commerce, Economics and Policy 10: 1950007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woodford, Michael. 2003. Interest and Prices: Foundations of A Theory of Monetary Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Jing Cynthia, and Fan Dora Xia. 2016. Measuring The Macroeconomic Impact of Monetary Policy at The Zero Lower Bound. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 48: 253–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagaglia, Paolo. 2013. Forecasting Long-Term Interest Rates with a General-Equilibrium Model of the Euro Area: What Role for Liquidity Services of Bonds? Asia-Pacific Financial Markets 20: 383–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Notation | Description | Steady State Value18 |

|---|---|---|

| Y | Output | 1 (normalization) |

| C | Consumption | 0.6114 |

| I | Investment | 0.2173 |

| L | Labor supply19 | 0.2308 |

| G | Government Expenditure | 0.119 |

| T | Lump-sum Tax | 0.1196 |

| Gross short-term interest rate | 1.01 | |

| Gross long-term interest rate | 1.0201 | |

| Gross inflation rate | 1.0039 | |

| Total debt | 1.5493 | |

| Total short-term debt | 0.0869 | |

| Total long-term debt | 1.4624 | |

| Long-term debt held by central bank | 0.2296 | |

| Long-term debt held by private sector | 1.2328 | |

| Steady state ratio of | 14.1864 | |

| x | Steady state ratio of | 0.1570 |

| Notation | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Capital share | 0.36 | |

| Depreciation rate | 0.025 | |

| Discount factor | 0.994 | |

| Habit formation | 0.7 | |

| Fixed cost in production | 0.2 | |

| Inverse of Frisch elasticity of labor supply | 5 | |

| Inverse of intertemporal substitution (risk aversion) | 2 | |

| Interest-rate semielasticity of money demand | 4 | |

| Calvo type price rigidity | 0.75 | |

| Price indexation | 0.5 | |

| Steady state mark-up Rate | 0.2 | |

| Portfolio Adjustment Friction20 | 0.01 | |

| Investment Adjustment Friction21 | 770.6056 | |

| Steady state lump-sum tax | 0.1196 | |

| Response to short-term debt deviation | 0.3 | |

| Response to long-term debt deviation | 0.3 | |

| Response to output | 0.25 | |

| Response to inflation | 1.5 | |

| Monetary-policy smoothing | 0.995 |

| QE Persistence | Output | Investment | Inflation | Long-Team Interest Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (4 years) | 0.38% | 0.97% | 0.26% | −50.84 bp |

| (6 years) | 0.51% | 1.29% | 0.41% | −49.46 bp |

| (8 years) | 0.68% | 1.71% | 0.62% | −47.56 bp |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, R. Evaluating the Unconventional Monetary Policy of the Bank of Japan: A DSGE Approach. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2021, 14, 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14060253

Wang R. Evaluating the Unconventional Monetary Policy of the Bank of Japan: A DSGE Approach. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2021; 14(6):253. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14060253

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Rui. 2021. "Evaluating the Unconventional Monetary Policy of the Bank of Japan: A DSGE Approach" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14, no. 6: 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14060253

APA StyleWang, R. (2021). Evaluating the Unconventional Monetary Policy of the Bank of Japan: A DSGE Approach. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(6), 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14060253