Abstract

Recently, there has been an ongoing global debate on the issues of energy safety, energy autonomy, and energy alleviation policies in developed and developing countries. The energy communities can integrate distributed energy resources, especially among local energy systems, playing a decisive role to support people around the world in the transition process towards sustainable development and renewable energy sources (RES). The main research dimensions of such a manifold approach are environmental sustainability, the reduction of greenhouse gases (GHGs) emission, the ordinal exploitation of RES, the social awareness in actions towards global consumerism in an environmentally caring manner, the increase of energy efficiency, and the pollution relief caused by the expansion of urban/built environment worldwide. This review study focused on the roles and the ways of how “energy communities” (ECs) could support contemporary energy management and priorities to ensure energy safety, autonomy, and alleviation, regionally and globally. In this context, a systematic, last-decade publications of ECs was conducted and the retrieved documents were organized in alignment with the following four groups of literature overview. Group 1 covered the dimensions of technology and environment, being coupled with Group 2, covering the dimensions of socio-culture and anthropocentricity (mainly focusing on the built environment). A similar coupling of Group 3 and Group 4 was made, where Group 3 covered the legislative dimension of ECs and Group 4 covered the ECs devoted to Europe–European Union (EU), respectively. The emerging key literature aspects, the proposed measures, and the applied energy policies on ECs were also conveyed and discussed.

1. Introduction

In recent years, with the accommodation and control of increasing renewable energy (RE), the power system has undergone a paradigm shift, leading to more Decentralized Energy Resources (DERs) in the grid. Consequently, Energy Communities (ECs) are a cooperative strategy of novel sharing RE DERs, in alignment with consumption minimization and flexible utilization of energy by active consumers to ease the high energy loads of the power grid (Weckesser et al. 2021). ECs are recognized by the EU and the Clean Energy package as a concrete spectrum of collective energy actions that foster citizens’ participation across the energy systems. In this context, there are approximately 3500 ECs in the EU (in the reference year 2019) and in Denmark specifically, there are around 700 (in the reference year 2019) (Weckesser et al. 2021). The development of ECs is related to meeting specific social and/or environmental targets, where local communities are given the opportunity to share or exchange energy resources in a non-commercial manner (Weckesser et al. 2021).

An energy community initiative involves responsibilities and benefits sharing, being derived from energy production. Notwithstanding the recent regulations of EC projects that are recently conceptualized in remote mountainous and island areas, they actually existed before DER use became a common reality (Cielo et al. 2021).

At the European RED-II Directive, ECs support a legal tool enabling an open and voluntary participation of stakeholders, being autonomous and effectively controlled in the nearby areas of the renewable energy projects installed. These shareholders can be members or natural persons, small and medium enterprises (SMEs), or local public (municipality) authorities while the primary purpose of an EC is caring to offer environmental, economic, and social community benefits among those (shareholders) of local interest, where ECs are operative. Contrarily, the financial profits are not prioritized in Ecs. Subsequently, ECs play a decisive role for the achievement of decarbonization, the confrontation of energy poverty, and the realization of energy justice (Streimikiene et al. 2021) or, similarly but with a more political meaning, energy democracy (Cielo et al. 2021).

EC structures, being foreseen in the EU regulation, have recently been proven as legally credible and regulatory realistic among EU state members. Considering the novel rules on energy production and use as well as the contemporary economic incentives, the availability of technical and economic simulation tools is crucial to determine if the initiative is both competitive and advantageous in terms of cost–benefit. It is noteworthy that simulation can take into account different entities working together for the EC: the community itself and a technical partner taking care of installation and management; energy savings and reduction of greenhouse gas (GHGs) emissions that positively impact the environment; and positive economic returns and new working possibilities for the EC technical partners who are responsible for its maintenance and management (Cielo et al. 2021).

In a relevant study, it was shown that among energy communities there is a pronounced importance of power systems that they have been transitioning from systems based on traditional fossil fuel generators to those involving renewable energy (Jo et al. 2021). Indeed, RES in power systems are feasibly proven capable and desirable to tackle environmental problems caused by energy resources’ utilization and generating designing and operation problems in power systems, such as that of the duck curve, and the increase in flexibility requirements (Jo et al. 2021). Resolving such problems requires system operators to operate thermal and hydro works as traditional bulk power generation resources. Nevertheless, such solution demands high investment costs due to the wide diversification of RES. Subsequently, in overcoming problems generated by traditional generators, there have been several research attempts to adopt RES technologies in both large-scale and small-scale levels. In particular, the key aspect of large-scale approaches is the appropriate management of the output of RES-fed power systems in the High Voltage (HV) mode. Moreover, an increase of the amount of curtailed renewable energy is forecasted due to the trend of RES widespread use (Jo et al. 2021).

Another terminology abided to ECs is that of renewable energy communities (RECs) which are particularly interesting as generation is moved to the edge of the power system, then, the Low Voltage (LV) grid can be stressed. In this energy route, the ongoing sharing of photovoltaic (PV) electricity generation could lead to voltage violations in LV grids, reforming the existing load profile with potential changes inducing reversed and varied power flows. In this context, the more active members rise proportionally, the risk of overloading increases especially among smart communities with peer-to-peer trading and high adaptation of PVs to energy grids and mitigation strategies are proposed (Weckesser et al. 2021).

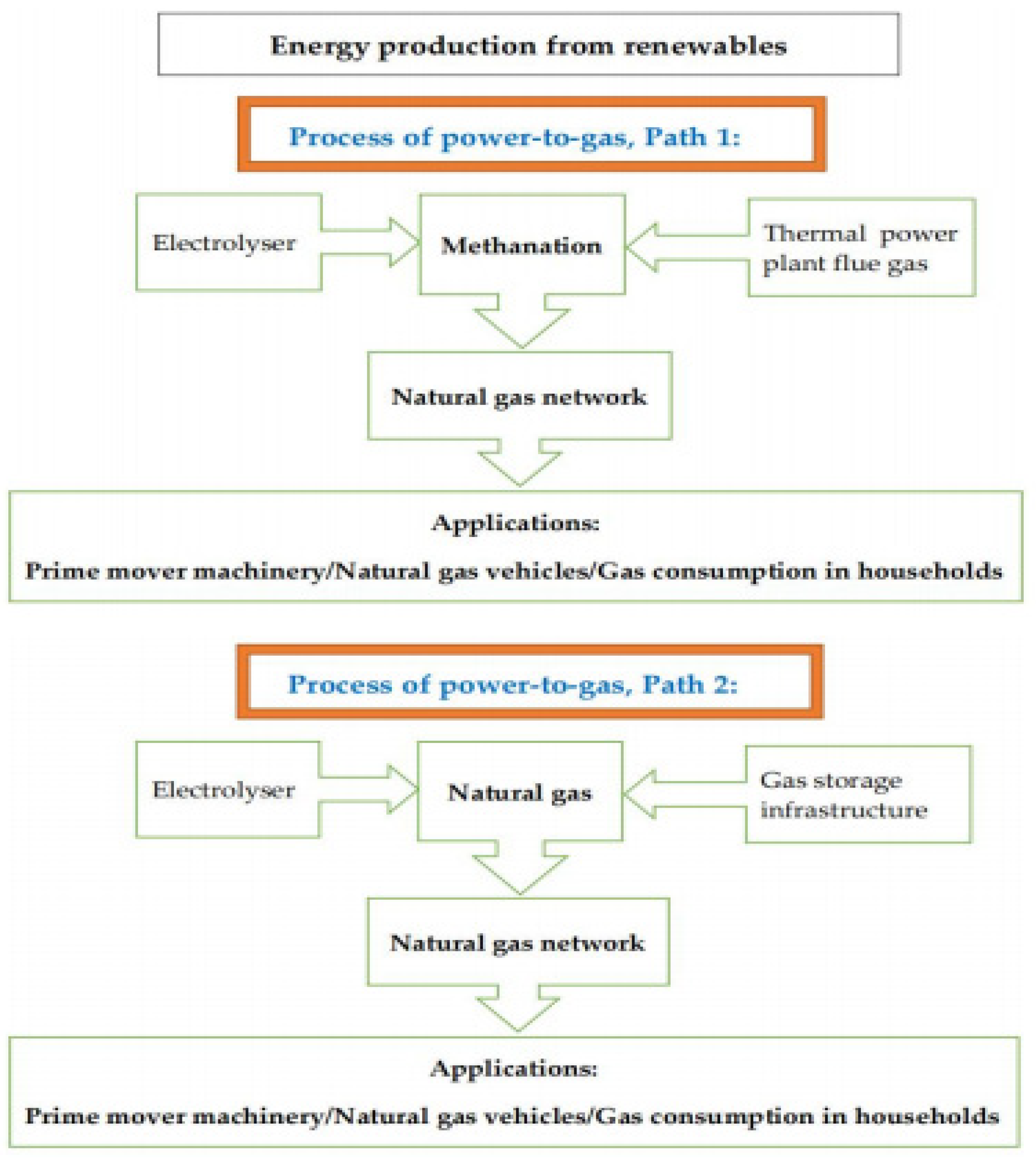

A typical REC is functional under a peer-to-grid (P2G) energy sharing policy. Such an energy sharing policy for the natural gas network and distribution is illustrated at Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Procedural profile of the P2G process. Source: Z. Liu et al. (2021).

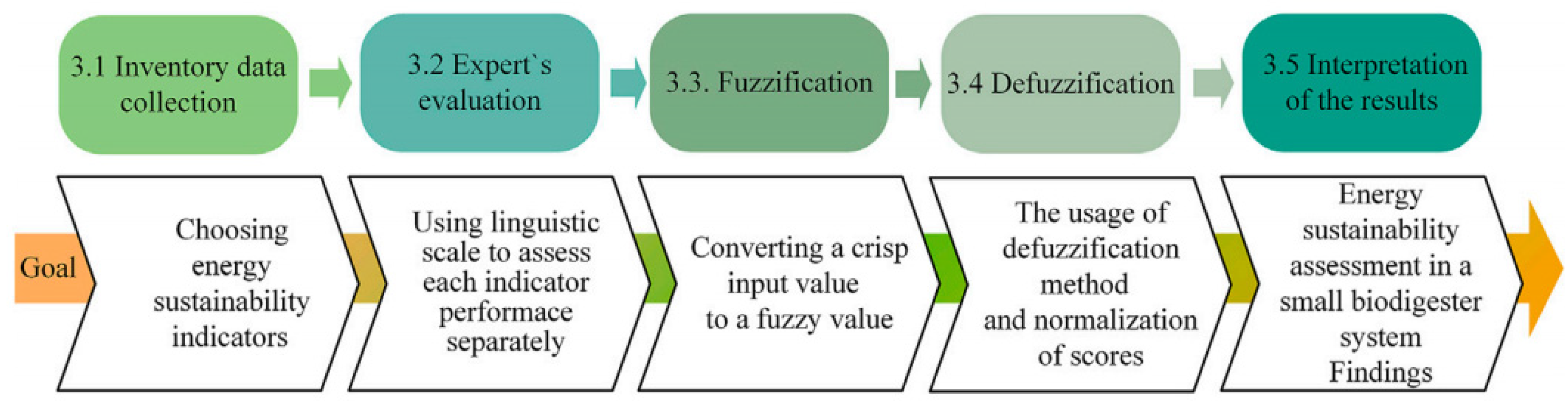

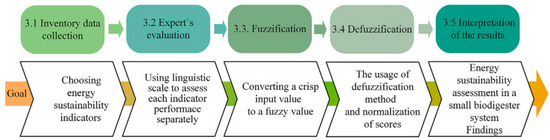

Another energy community (EC)-based framework involves energy life cycle assessment (LCA)-based indicators based on fuzzy numbers as key determinants of sustainable energy performance. Such ECs enable decision-makers to reach a consensus while overcoming problematic issues such as human error, ambiguity, and uncertainties in calculations, Figure 2 (Kluczek and Gladysz 2022). These indicators are suitable for an effective assessment due to LCA appropriateness and robustness to meet Agenda 2030 goals, while simultaneously determining energy indicators and sustainability evaluation methods based on life cycles dedicated to the energy sector (Kluczek and Gladysz 2022).

Figure 2.

A schematic framework for energy sustainability (impact) assessment based on expert knowledge. Source: Kluczek and Gladysz (2022).

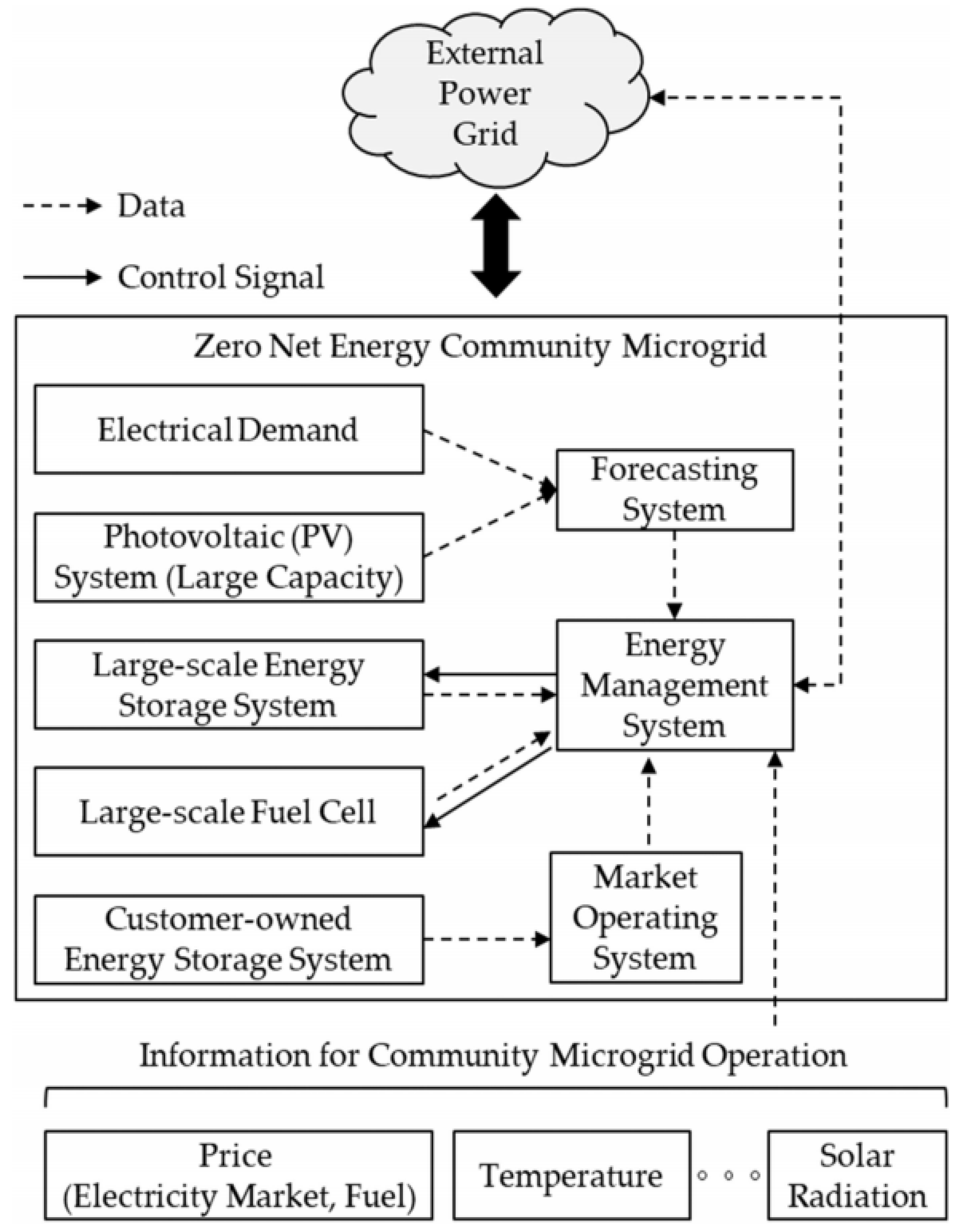

In Figure 2, a methodology for energy sustainability evaluation by incorporating fuzzy numbers is shown (Kluczek and Gladysz 2022). This methodology is based on expert judgments while an energy sustainability assessment is based on choosing specific and physically measurable indicators. Then, experts use linguistic scales to quantitatively assess these indicators’ performance by using fuzzy (and later defuzzified) numbers of the integrated-aggregated energy sustainability assessment. Environmental, economic, and social indicators are considered while developing an energy-related sustainability index in which these three aggregated sustainability indicators are described as fuzzy numbers (Kluczek and Gladysz 2022). The economic indicators include energy subsidies, and they may be economically costly to the potential end-user and taxpayers; thus, the overall/final value of economic energy sustainability is influenced. Simultaneously, increased GHG emissions into the atmosphere can be reported. Moreover, energy subsidy indicators affect the developmental prospects of economies and their engagement in energy subsidy planning. Therefore, the key drivers in developing countries are the set of income per capita (including subsidies and wider economics reforms) and net energy criteria that are designed and interrelated (Kluczek and Gladysz 2022). The procedural operation of a community microgrid is depicted in Figure 3.

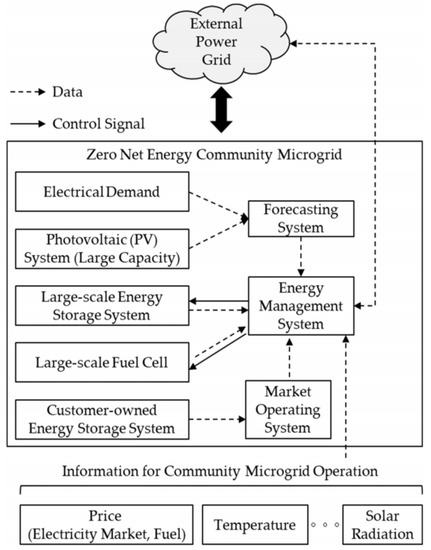

Figure 3.

The procedural operation of community microgrid. Source: Jo et al. (2021).

Based on Figure 3, a zero net energy community microgrid can be defined as a distribution system for a community, which offsets all of its energy use from the distributed generation resources and Energy Storage Systems (ESSs) available within the environment established for the community. All information referring to the operation of microgrids is collected by the community microgrid operator regarding the DERs and the electricity demand. This information can be utilized by the operator to meet electricity demands by determining the optimal schedule of the ESSs and Fuel Cells (FCs). Only in cases where the power balance is not met, then the additional demand can be met when the microgrid receives electricity from an external power grid. However, inefficient operation can be caused in cases where the operator cannot control the charging/discharging of the customer-owned ESS (CESs), resulting in the increased capacity of the ESSs and FCs in the microgrid (Jo et al. 2021).

Another critical point that cannot be undermined is the grid impact, while comparing different optimized operational strategies of RECs with a shared Battery Energy Storage System (BESS). The REC configuration in the distribution grid is, therefore, varied to account for various power flow scenarios/cases (Weckesser et al. 2021). In the relevant literature, it was stressed that the design criteria for distribution grids depend on the supplied customers; thus, different grid types such as city, suburban, and village can be considered. In this configuration, the distribution grid contains two low-voltage and one medium-voltage grid, while various energy community configurations based on type of customers can be assessed, following relevant control strategies (Weckesser et al. 2021). The developed strategies are related to the following targets: Strategy 1 concerned the EC’s goal aiming at the lowest system cost for electricity for the EC in energy markets. Strategy 2 concerns the relevant EC optimization through peak shaving and peak power exchange versus total system costs. Strategy 3 concerns the maximization of electricity consumption by the self-sufficiency (locally consumed energy or energy stored in the communal battery) of the EC’s own PV. The battery can be located either behind the meter (Strategy 3a) or in front of the meter (Strategy 3b), and this differentiation directly impacts taxation. Strategy 4 concerns the diversified connection schemes and setups of voltage feeders at different distribution grid types (city, suburban, and village). This operation-related strategy involves combinations of low- and medium-voltage feeders as well as different sectors of the distribution grid, such as the household sector and the commercial customer sector (Weckesser et al. 2021).

The problem addressed by this review paper is determined by the fact of unstable socioeconomic conditions that are prevailing due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as well as the socio-economic crisis spread by the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic worldwide. Both of these globally affected situations are causing significant strategic changes for meeting the targets of energy demand, production, and consumption patterns in the households and industrial sectors. In this context, there are also challenging issues including the development of renewable energy, the environmental protection by meeting the setting targets of GHG emissions reduction, and the national energy policies and strategies of energy production downsizing.

The aforesaid constraints of (a) the COVID-19 pandemic and (b) the Russian invasion in Ukraine both make global energy a big problem, especially in the second half of 2021 which was further defined by high and steady increases in energy prices and the subsequent threatening situations of energy poverty and poor energy alleviation. In response to this problem, the scope of this review study is to collect and systematize the generated energy management of policies and initiatives that have been deployed and promoted in order to confront these energy-induced problems. Subsequently, the scope of this review study is two-fold: (a) to reveal the role of ECs and (b) to determine the main research priorities under which the ECs are operated, also revealing what the key determinants and the priority issues with which the ECs are related at regional, national, and international levels of investigation are.

Based on the aforesaid scope of this review study, the measures of energy consumers’ alleviation from this economic burden can be detected, being able to further support national and international energy planners to design and support the development of a variety of feasible solutions and realistic energy-related choices, such as the shift from fossil fuels to RES, the increase of energy efficiency, as well as the identification of stressors for the reduction of climate emissions in alignment with finding new energy suppliers.

2. Methods and Analyses

This review study has been organized in alignment with two groups of literature themes. In particular, all collected studies were registered in the Scopus database, all containing the key phrase of “energy community”. Therefore, a systematic and last-decade-intensified literature retrieved all documents referring to the key phrase of “energy community” during the last decade of publication (period of 2010 onwards). The period of literature search and data collection was within the first quarter of 2022. Then, the “energy community” results of group 1 covered the dimensions of technology and environment, while the other group, group 2, covered socio-cultural and anthropocentric (mainly focusing on the built environment) dimensions. Table 1 contains the studies’ allocation with subcategories per group and per type of context, while the in-groups’ joint studies (having two or more common contexts of investigation) are collectively presented in Table 2. Moreover, the miscellaneous studies regarding the energy communities (covering mainly those geographical and sectoral contexts) are illustrated in Table 3, accordingly.

Table 1.

Allocation of literature dimensions into contexts of energy communities per group: Group 1—technological and environmental dimensions of energy communities, Group 2—socio-cultural and anthropocentric dimensions, Group 3—legislative dimension, Group 4—Europe–European Union (EU) dimension of energy communities.

Table 2.

In-groups’ allocation of literature dimensions into contexts of energy communities in two pairs: (a) Groups 1 and 2, (b) Groups 3 and 4 (studies are presented in reverse chronological order and in last name of first author alphabetical list).

Table 3.

Miscellaneous fields of energy communities referring to geographical and to sectoral contexts of analysis (studies are presented in reverse chronological order and in last name of first author alphabetical list).

Based on the allocation of studies into the aforementioned four groups in Table 1, it can be seen that in the current planetary, environmental, and social emergency, it is essential for researchers to seek strategies for sustainable development. In this context, the implementation and envisaging of the Social Development Goals (SDGs) in contemporary societies impose sustainable development strategies to take action by ascertaining the protagonistic roles of citizens’ rights and responsibilities (Otamendi-Irizar et al. 2022). Given that global challenges must be addressed through local action, the transition towards energy decentralization through Local Energy Communities (LECs) is also considered of utmost importance, making it important to identify the key characteristics in order for LECs to act as drivers of effective operation, local sustainable development, and social innovation (Otamendi-Irizar et al. 2022). These strong linkages developed among the ECs with the technological, environmental, social, and humanitarian dimensions of the relevant literature are organized and mapped into Table 2a,b.

Based on Table 2a,b, it can be stressed that LECs, another entity related to ECs under multi-energy systems, have been locally and collectively organized in order to support the development of sustainable energy technologies through consumers’ engagement, offering various benefits to them, and contributing to planned energy and climate objectives. Subsequently, LECs are expected to decisively support energy transition, since they also consist of multiple distributed energy systems (DESs). DESs interconnect local grid and heating networks, while also sharing power and thermal energy with no costs for (community) users (Yan et al. 2020).

LECs are also suitable for large scale development since LECs can utilize a collective self-consumption framework in order to require new control methods which are linked to users’ preferences. In the relevant literature, such a LEC-based model with diverse actors, i.e., photovoltaic generators, electric vehicles, storage system, and tertiary buildings, has been reported (Stephant et al. 2021). Moreover, pushing the boundaries of self-sufficiency, LECs rely on load demand forecasts; thus, scheduling energy usage ahead of time. In such a selection, the forecasting method sustains two characteristics: quality and value. Such a traditional forecasting method of ranking is based on the quality metric named “Mean Absolute Percentage Error” (MAPE) (Coignard et al. 2021). It is also noteworthy that LECs are considered key determinants of sustainable cities, being directly relevant to the integration of electric mobility with energy systems based on RES; thus, lowering the adversely affected environmental conditions in urban areas and supporting the materialization of microgrids. Typical energy-consuming applications at ECs in urban areas are those of electric mobility services, which commonly include the use of electric buses, car sharing, bike sharing, and e-scooters. All these services are challenging the transportation modes in a sustainable manner, especially in densely occupied built environments such as those of university campuses (Piazza et al. 2021).

Table 3 shows two representative fields of ECs referring to geographical and sectoral contexts of analysis. In particular, in the upper half of Table 3 is presented a detailed literature coverage of ECs in alignment with the geographical context of analysis. Regarding the geographical context of ECs, it is noteworthy that one of the main research objectives is to couple them with central/national power systems by utilizing each country’s technological status of energy development, such as well developed heat supply network at the built environment and well designed grid of electric vehicles charging stations. In such a case, Backe et al. (2021) stated that building heat systems and electric vehicle charging can jointly achieve a cost-efficient decarbonization in the European power market. These authors determined a 0.4% transmission expansion decrease by 0.4% and an 3% average cost reduction of European electricity cost by the combined development of Norwegian heat systems with the European power system. Moreover, the provisional strategy of 20% energy supply of Norwegian buildings with district heating fueled by waste and biomass and the remaining electric heating supply by heat pumps can result in a 19% energy cost decrease in Norway (Backe et al. 2021).

Based on Table 3, a wide geographical and sectoral dispersion of research production for ECs can be noted. Indeed, a large portion of literature production is related to ways of regulatory opportunities, barriers, and technological solutions while integrating energy in buildings and districts with certain and formalized planning contexts as that of the EU energy community framework (Tuerk et al. 2021). Moreover, economic optimization and market integration offer new use cases, revenue opportunities, and at the same time, new insights of investigating regulatory limitations regarding EU Clean Energy Package provisions (Tuerk et al. 2021). Regarding the geographical and the sectoral contexts of ECs, Table 3, it is also noteworthy that formal institutionalization of ECs is neither a precondition nor a guarantee of implementing energy regionalism (Herman and Ariel 2021). However, national ECs should be based on regulatory convergence (such as in the case of EU). The main goal of converging ECs in several southeast EU member states is to integrate and harmonize the energy sector of the non-EU member countries with the energy sector of the EU by (among other things) offering the prospects of easier access to foreign investments. This however requires implementation by those countries of the mandated rules as set by the ECs, which in practice are similar to the rules and laws that are required within the EU itself (Verhagen 2019).

However, the introduction of a political integration model in this highly sensitive research area of EU energy cooperation might run the risk of hurting the incremental technical integration process that has slowly emerged over the past few years as in the case of the politically fragmented MENA region/the energy community with southeast Europe. This critique makes questionable whenever European Commission (EC) insists on repackaging its enlargement concept in regions with very different types of relationships vis-à-vis the EU (Tholens 2014). In such an EC development, a response on the capacity expansion of the cross-border transmission and national generation and energy storage within the EU electricity and heating system with and without ECs among specific European countries is technically challenging. Among the critical attributes of ECs, their flexibility makes it plausible to investigate differences of flexibility responses by ECs towards local versus EU cost minimization and global cost minimization (Backe et al. 2022). From an environmental side, EC development can decrease total electricity and heating system costs on the transition towards a decarbonized EU system in alignment with the 1.5 °C target; thus, less generation and energy storage capacity expansion on a national scale can achieve climate targets (Backe et al. 2022).

In this context, ECs can provide a joint legal and regulatory framework for organizing and governing a community while providing new regulatory space for specific activities and market integration, such as innovative Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) enabling a wide range of actors to be actively involved in creating and operating energy communities (Tuerk et al. 2021). This “locality” characteristic is crucial since local communities do not often control their DERs such as electric vehicles, home equipment, or electric heating. Therefore, the comparison of a novel local energy market (LEM) framework with a low-tech price reaction mechanism to coordinate DERs in the context of the recent French collective self-consumption framework was deployed by Coignard et al. (2020). This research focus was two-fold: to develop a literature overview at the intersection between transactive energy concepts and recent regulations for collective self-consumption, as well as to evaluate the performance of the proposed LEM on a simulated platform with ten households over a year. They were practically shown ways of the coordination requirements needed to reach different levels of self-sufficiency for solar-based ECs (Coignard et al. 2020). Similarly, Radl et al. (2020) argued that under current market conditions, battery energy storage systems are rarely profitable for increasing PV self-consumption but RECs enable individuals to be prosumers without the necessity of owning a PV system, thus, fostering more community-centered PV investments in the short term (Radl et al. 2020).

Further investigating the conceptualization and relevancy of Differentiated Integration (DI), it can capture dynamics and processes often neglected in established approaches. DI can be developed beyond EU borders, since it entails more than the inclusion of non-EU Member States in selected EU policies (Kurze and Goler 2020). Such an external DI implies the extension of general integration dynamics (i.e., widening, broadening, and deepening) beyond EU borders and, to this end, energy communities can be adopted by international organizations that are initiated by the EU through processes of deepening, broadening, and widening since its foundation. Such a DI operation can support researchers’ understanding of the EU as a transformative power (Kurze and Goler 2020).

Overall, the fact that the main goal of materializing qualitative overviews of EC concepts and strategies at the national and global levels of analysis cannot be undermined. Such a quantification should realistically frame the development of ECs to understand the most feasible actions leading to economic growth and sustainable development. To achieve this multi-parametric objective, the following are recommended: (a) an updated review on policies dealing with ECs at EU and their state member levels; (b) a qualitative overview of European-funded projects under EU-funding programs, such as that of the Horizon 2020 work program; and (c) a qualitative overview of selected and mostly successful existing ECs in Europe and abroad. Such a three-pronged methodological approach of ECs can generate thoughtful considerations and useful experiences to be learned for the transition implementations of real cases and actions to be undertaken (Boulanger et al. 2021).

2.1. Technological and Environmental Contexts of Energy Communities—Group 1

The literature production devoted to technological and environmental contexts of ECs revealed that the technological development, such as flexible and exploitable RES, types of fueling local building heating systems (electric or gas), as well as a well-developed grid of electric vehicles fleets and charging stations play a decisive role in strategic plans drawn against energy poverty. However, there was also a critique raised of such an “energy poverty regionalism”. Indeed, treating energy poverty by energy cooperation stresses that cooperation can be more successful at the regional level, but it largely fails to understand and conceptualize energy cooperation as part of the wider regionalism phenomenon (Herman and Ariel 2021). In this context, it was meant that security and geopolitics are prioritized with other factors of regional integration processes, such as motivations and interests offered. Two regions which exhibit extensive energy cooperation also differ in several ways to each other: North America and the European Energy Community (Herman and Ariel 2021), arguing that a regional anchor is key in North American and European energy regionalism (Herman and Ariel 2021). In Table 4, the literature overview of the technological context energy storage, Group 1, is presented.

Table 4.

The context of energy storage—Group 1 (studies are presented in reverse chronological order and in last name of first author alphabetical list).

Based on Table 4, it is critical to note that there are cases where the impact on the grid depends on the battery operation strategy. In particular, the minimum and maximum (especially in LV grid) voltages are affected by the battery location. Moreover, a battery positioning at the end of the feeder or at the commercial customer, does not greatly impact the voltage. Battery position also slightly impacts the loadings of LV and MV lines, thus, the favored positioning of the battery is that of the beginning of the feeder, especially at the connection of the communal battery (Weckesser et al. 2021). Under certain energy production schemes, peak shaving should reach up to a 70% economic and technical maximum, thus, further peak shaving is detrimental to the system’s effectiveness. Similarly, at energy plans when a break-off point exists for energy communities, then, only the peak shaving cases up to 30% Pmax are commonly considered, since the utmost importance goal is to relieve the grid (Weckesser et al. 2021). In Table 5, the literature overview of the context of renewables, Group 1, is presented.

Table 5.

The context of renewables—Group 1 (studies are presented in reverse chronological order and in last name of first author alphabetical list).

Based on Table 5, it is noteworthy that ECs play a determining role towards the achievement of energy transition goals, but a full commitment requires a coordinated designing and operation which it is not always possible to be managed by the community itself. The supportiveness of aggregators and Energy Service COmpanies (ESCOs) could be feasible under the precondition that their goals are tuned to those of the community, not generating agency problems (Fioriti et al. 2021b). In this respect, it remains challenging in an open, competitive, and resilient electricity market to ensure the harmonization among varied rates of energy production in the recently developed era of massive RES penetration. Subsequently, increasing the modern pricing schemes can effectively incentivize eager users to meet their managerial plans while modifying their energy consumption patterns. The existing energy pricing schemes (such as in cases of real time pricing) have to equally treat all users, not adequately compensating for behavioral changes, thus mitigating the behavioral change dynamics (Mamounakis et al. 2019).

In parallel, according to Table 5, a growing literature production on energy justice implied that vulnerable and energy-poor households are severely affected by complex energy injustices in disproportional energy transition. RECs sustain the potential to support and motivate citizens (especially those groups which are underrepresented) to pursue energy transition as a just transition. The participation of citizens to RECs particularly benefits low-income and energy-poor households by affordable energy tariffs and energy efficiency measures. Such an energy justice framework could analyze RECs’ social contributions in different countries (Hanke et al. 2021).

The EU ambitious commitment is to adopt low carbon energy and drive up to 2050 economy transition and, to this end, ECs being considered as legal entities where different actors and citizens cooperate in energy generation, storage, and management; they are all protagonists (Viti et al. 2020). In this context, low carbon transition is linking sustainable energy development path with RES, thus primarily addressing the energy poverty vulnerability and justice issues (Streimikiene et al. 2021). Community-scale energy planning should also play a decisive role towards developing sustainable ECs through conscientious efforts to realize energy and emission plans of local interest. These ECs, as well as the synergies developed at community and energy planning strategies, are all rather unrepresented areas for the developing world (Ugwoke et al. 2021).

Conceptually, RECs are defined as citizens, SMEs, or local governments who collectively invest, produce, and use local renewable energy, with private citizens controlling a majority stake. RECs play a decisive role in a community goal of sharing an increase of sustainable energy production while overcoming participation barriers. Therefore, towards fostering citizens’ intent to participate in a REC, it is important to firstly understand what are the determining characteristics of a REC (Conradie et al. 2021). In this respect, the impact of a REC on policy level is yet to be seen, despite the fact that energy decentralization and energy democratization have been extensively discussed in academic/research levels. Among the EU state members such an implementation at policy level remains a state responsibility, knowing that those national policies are still overwhelmingly centralized. This regulatory framework determines the decentralization and the democratization of energy and, subsequently the “just transition” accomplishment (Heldeweg and Saintier 2020).

Another critical point of popular research interest is the joint relation of net-zero energy communities powered by RES. The transition to community-level net-zero energy systems implies the identification and selection of the best energy technologies that should be operative at local level while simultaneously considering technical, economic, environmental, and social aspects of wellbeing. In such a perspective, the consideration of true costs and benefits of energy use can be determined by a cradle-to-grave life cycle perspective (Karunathilake et al. 2018). Solar and wind energy are the significant renewable energy sources that can be used to tackle the climate change issue. Therefore, in the relevant literature, different architectures of community-level energy systems were designed and compared towards achieving a positive energy community in cold climate. Such a design proposed a centralized solar district heating network, which was integrated with renewable-based electricity network to cover the energy demand of a block of 100 houses in their heating and electricity needs. The proposed RES-based energy system consists of PVs, wind turbines, and stationary electrical storage (ur Rehman et al. 2019). In Table 6, the literature overview of the context of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) (including networks security), Group 1, is shown.

Table 6.

The context of ANNs (including networks security)—Group 1 (studies are presented in reverse chronological order and in last name of first author alphabetical list).

Table 6 notably revealed that contemporary approaches of energy integration and management should acceptably deploy local peer-to-peer (P2P) transactions in their communities. Such a P2P trading scheme requires a comprehensive understanding and planning of various key aspects of methodological significance such as that of peer privacy, computational efficiency, network security, and operational economics (Wang et al. 2021).

2.2. Socio-Cultural and Anthropocentric Contexts of Energy Communities—Group 2

In Table 7, the literature overview of the context of local energy, Group 2, is presented.

Table 7.

The context of local energy—Group 2 (studies are presented in reverse chronological order and in last name of first author alphabetical list).

Based on Table 7 it can be stressed that, through the deployment of distributed generation, consumers can provide significant values in the energy sector transformation in alignment with energy efficiency improvements, and sustainable energy-related practices’ adoption. The precondition of forming ECs is the occurrence of common interests and goals among the consumers. Through ECs, consumers are capable to commit their individual and collective goals at an economic, environmental and social point of view, and to simultaneously contribute to the decarbonization of the energy system (Gjorgievski et al. 2021).

Among the most important issues regarding the local energy features of the ECs involves the encouragement of customers to reduce their connection capacity to avoid higher costs, mainly due to the capacity-based network tariff structures. However, the administrative grid sustains certain connection capacity and overloading beyond that limit can increase connection capacity, forcing prosumers to proceed in such an extra pay of their electricity bill for the rest of the year. Therefore, the energy generation and consumption profiles of LECs have to be optimized taking into account the comfort level of occupants (Tomar et al. 2021).

Another critical local energy-oriented issue is the fact that cities’ growth implies ECs promoting distributed energy resources and implement measurable energy efficiency. For a better understanding of ECs motivation, research should improve a Pareto Optimization of existing open source models, targeting both costs and carbon emissions. In this context, clustering algorithms are able to improve models’ scalability and performance (Fleischhacker et al. 2019).

In an applicable context of local energy generation, the following cases can be denoted:

- -

- “Clean Energy for All Europeans” legislative package is the core of European energy policy enabling citizens and communities to actively adopt and promote local energy generation, consumption, and trading. While the literature on energy community business models is sporadic, a stable systematization of community arrangements is missing; thus, there is still space for further motivation and active contribution of energy communities in the future of the European regulatory framework (Reis et al. 2021).

- -

- The “Clean Energy” package supports the smoothing process of energy transition recommended by the EU. Energy transition can, therefore, be achieved through measures and policies that can ensure the security, the sustainability, and the competitiveness of energy supply systems. Such measures and policies entail the introduction of suitable physical and regulatory infrastructures to meet energy market requirements, integrate RES, and ensure security of the energy supply, while a risk-based approach in the electricity sector is managing electricity problems in a proactive manner (Mutani et al. 2021).

In Table 8, the literature overview of the context security of supply, Group 2, it is presented.

Table 8.

The context of security of supply—Group 2 (studies are presented in reverse chronological order and in last name of first author alphabetical list).

In Table 9, the literature overview of the context of buildings, Group 2, is presented.

Table 9.

The context of buildings—Group 2 (studies are presented in reverse chronological order and in last name of first author alphabetical list).

The modern revolutionary changes in power delivery systems with the advent of smart and flexible grids require systems that are functioning at a way of intraoperation and seamless integrated technology. Therefore, research scenarios should pave the way for energy clusters that call for new methodologies applied at the dynamic energy management of DERs (Rosato et al. 2021). In this respect, the relevant literature production has been directed to examine heat harvesting being rejected from the cooling and refrigeration systems in buildings showing high year-round cooling and refrigeration demands (e.g., ice arenas and grocery stores), and using heating excess to heating purposes of other nearby buildings. Moreover, the integration of a small group of buildings with diverse thermal demands via a network of low- and micro-thermal temperature to allow harvesting of thermal energy wasted and shared at minimal thermal and mechanical losses (Di Lorenzo et al. 2021).

2.3. Legislative Context of Energy Communities—Group 3

The legislative dimension of ECs is one of the most challenging and creative dimensions of regional (Tsagkari 2021; Buschle and Karova 2019; Minas 2018; Hroneska 2014) and sectoral (De Lotto et al. 2022; Iakovenko 2019) interest. In such a multidimensional context, the EU is also experiencing an ongoing nuclear renaissance; thus, this development accounted for primarily by the increasing energy demands of all EU member states, bringing once again to the fore the often forgotten-about European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom). A prospect of increasing nuclear energy production in the EU is increasingly gaining impetus, especially through the current fuel crisis generated by the Ukranian–Russian contradiction, making it highly important to set and comply with rules and instruments provided under the Euratom Treaty from a legal point of view. The Euratom Treaty’s reputation has been damaged, being characterized from a literature corpus as an “undemocratic treaty”, especially regarding the insufficient institutional leverage given to the European Parliament. Taking the Lisbon amendments to the Euratom Treaty into account, there was still much to be desired (Cenevska 2010). Therefore, research attention should be drawn to existing problems that could contribute to the establishment of a common integrated energy market in SE Europe and the EU (Mihajlov 2010).

In a legal terminology point of view, it is notable that in the absence of a single definition of security of supply, one may observe diverging views among EU state members as to the policy required to ensure it. Indeed, in this context, the entity of “security of supply” is considered a core issue in EU energy law and it is an integral part of the EU’s energy strategy. In many cases, this entity is an important argument to structure EU’s rules on competition on the internal market. Moreover, both Directive 2009/73/EC2 (also called ‘Gas Market Directive’) and Directive 2009/72/EC3 (also called ‘Electricity Market Directive’) recognized “security of supply” as a basis for the imposition of public service obligations (PSOs) on undertakings operating at these markets (Iakovenko 2019). Despite this, EU legislation does not lay down any across-the-board definition of the meaning of security of energy supply. Moreover, there are no explicit clarification criteria for cases in which state measures that guarantee security of supply fall within the scope of the Article 106(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU) or Article 107(3) TFEU. Therefore, further analysis can clarify the Articles 106(2) and 107(3) TFEU in the state of evolution of EU competition law, taking into account that EU member states use their discretion to decide on national services of general economic interests (SGEIs) objectives or the need of investment aid (Iakovenko 2019). In Table 10, the literature overview of the context of legislative framework, Group 3, is presented.

Table 10.

The context of legislative framework—Group 3 (studies are presented in reverse chronological order and in last name of first author alphabetical list).

Recently, the so-called Clean Energy For All Europeans Package (Winter Package) provided all EU with a new set of legal acts in the area of energy regulation. It can be signified that all these acts try to bring an answer to climate change and close environmental catastrophe. Those acts (directives and regulations) bring to life many instruments and institutions aiming to fight the climate change and global warming. One relevant instrument is that of “citizen energy community”, being introduced and defined by art. 2 sec. 11 of Directive (EU) 2019/944 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on common rules for the internal market for electricity and amending Directive 2012/27/EU (O. J. L 158, 14.06.2019, p. 125). Another relevant instrument is that of “renewable energy community”, which was introduced and defined by art. 2 sec. 16 of Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources (O. J. L 328, 21.12.2018, p. 82). All those institutions are categories of “citizen energy initiatives” (sec. 43 et seq. of preamble to Directive 2019/944).

Moreover, regarding the considerations of legislative framework among ECs, it can be denoted that there has been an organizational transfer from the EU to the EC, while, at the same time, the transposition of EU law into the contracting parties of southeast Europe (SEE) and beyond has also proceeded (Tangor and Sari 2021). In such a context it is notable the lack of national legislation or capacity to implement policies in SEE which would also protect public health and international Treaties, being proven highly capable to curb air pollution. The Energy Community Treaty that extends the EU’s internal energy market to SEE countries is, therefore, both an opportunity and a threat which can function as enabler to healthy energy forms, or blocking in SEE coal power that fuels climate change and air pollution. The Treaty also motivates public health experts to become engaged in (Stauffer 2016).

2.4. Europe–European Union (EU) Contexts of Energy Communities—Group 4

In this group of Europe–EU context, it can be inferred that the congestion management and the capacity allocation show that the SEE Regional Electricity Markets (REM) deal with the same priority issues as the other REMs do, and that the progress of REM are a feasible natural step towards the creation of a single European electricity market. Issues of concern are the EU membership perspective of the SEE countries and the expectation that the SEE REM shall become part of the internal electricity market, as well as the overlap between some members of the SEE REM and the other European Regulators Group for Electricity and Gas (ERGEG) ERI (Karova 2011). In a similar study, the emergence of the EnC of SEE should abide to the EU’s external energy policy, the specific regional approach of the EU at the Western Balkans, and the neo-functional ideas of those European Commission officials who are crucially involved in the process. Those officials involved are guiding a “popular” version of neo-functionalism as the idea that peace can be established with integration starting in a highly technical area and with creating the institutional capacity for a possible spill-over into other areas. EU’s rules and institutions in the energy sector make the EnC as an innovative new mode of governance in SEE (Renner 2009). In Table 11, the literature overview of the Europe–EU contexts of ECs, Group 4, it is collectively presented.

Table 11.

The Europe–EU contexts of ECs—Group 4 (studies are presented in reverse chronological order and in last name of first author alphabetical list).

Based on Table 11 data, significant findings regarding the locality and the decentralized characteristics of ECs can be inferred. Indeed, while ECs powered by RES should play a pivotal role to intensify RES technologies that reflect a growing wave of prosumer movements, especially in industrialized economies such as those of Japan, further development of ECs necessitate the appropriate regulatory framework to promote the concept of a sustainable regional community internationally, focusing on a more preferential approach to/model of ECs. Such a model can be suitable and adaptable to other ECs from the hosting country, in terms of membership, non-discriminatory treatment, barriers, support schemes as well as grid connection and management. In a real-world applicability of model designing, it is also noteworthy that the establishment of municipal power producers and suppliers (small-scale entities that cover local areas), they can lead to broader popularization and the use of distributed energy at both the maternal country and at its EC’s receptors/beneficiaries (Sokołowski 2021). Not surprisingly, a national or European model on ECs embodies the “assets” of nature, character, and scope of a regulatory model of its renewable energy sector, thus it can be subject to be attributed as “exporting tool” for the development of Ecs outside the EU (Sokołowski 2019). Based on Table 11, it can be argued that the today and the future of ECs in Europe can be determined, among other things, by:

- -

- The provision of ensuring that accession countries have to adopt EU rules as a condition of membership. However, the reliance on external incentives is limiting the effectiveness of bilateral accession conditionality, especially for pre-accession countries with uncertain membership prospects (Padgett 2012).

- -

- Political and legal aspects of electricity transmission contain those aspects that should explain the impact of the EnC Treaty and of the acquis communautaire on energy on the electricity transmission sector. In such a reality the status and the interconnection capacity among countries and the current level of cross-border electricity trades impose the need and the criteria for electricity transmission investments in the Energy Community of South East Europe (ECSEE): Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Romania, Serbia, UNM in Kosovo (Vailati 2009).

3. Discussion

Based on the literature overview on ECs developed above, it is noteworthy that within the last decade of analysis, an ongoing research interest of ECs in the field of energy poverty emerged, mainly focusing on the topics of European energy policy evolution towards the EU convergence among member states (Poiana 2017), the linkages between energy poverty and the provisional role of European Atomic Energy Community (McKee 2017), as well as the deployment of common energy planning that are directed to foster European neighbourhood policies (Kuhlmann 2014; Petrov 2012), like that of:

- -

- Aviation market in EU (including services, safety, security, air traffic management and environment protection) (Charokopos 2013) and

- -

- Accession countries adopt EU rules as a condition of membership and, in this context, energy interdependence is considered an evaluation criterion regarding the rule transfer effects of EU institutions relative to accession conditionality. In this context external incentives are prone to limit the effectiveness of bilateral accession conditionality, especially for pre-accession European countries with uncertain membership prospects (Padgett 2012).

Moreover, another research focus on ECs has been directed to the role of storage technologies, such as the battery energy storage system, which are expected to shape to future operation of micro-grids. However, current simulation tools underestimate their operating costs, which jeopardises their efficient use and deployment (Korjani et al. 2021).

There is also an increasing interest in multi-energy communities, which could become important sources of demand response flexibility, especially when equipped with storage. while solving local capacity congestions, enabling these ECs ability to partake in energy/reserve markets and subsequently improve their business cases. However, flexibility potentials and provision of multiple services are also prone to uncertain and challenging parameters of ECs modeling (Good and Mancarella 2019), thus, the deployment and the evaluation of KPIs with different generation and energy storage sizes could turn out to be conflicting: i.e., a large PV energy generation increases the self-sufficiency but it also periodically generates an energy surplus that exceeds local storage facilities that has to be sold on the grid. Besides, while a smaller generation can be totally self-consumed, it is not always able to meet ECs needs. Therefore, a totally self-sufficient and self-consuming community is an utopia (Cielo et al. 2021).

The designing steps are as follows: after this selection, an economic evaluation is performed and then the sizing is defined (Cielo et al. 2021). Subsequently, the conduct of a detailed business model supports researchers’ understand, given the most competitive sizing, by comparing different models and classifications including (Cielo et al. 2021): community-driven prosumerism, third-party-sponsored communities, a mixed sharing classification related to the previous two models. The research outcomes of the proposed methodology are opt to measurable considerations regarding self-consumption indexes, self-sufficiency levels related to reducing the greenhouse gases emission, while eventually proposing some possible/feasible developments of the proposed methodologies (Cielo et al. 2021). The tasks of ECs locally producing (a) the energy needed for the load, (b) the design of the active part of the REC the are not easy endeavours (Cielo et al. 2021). Therefore, RECs research and their potential impact on the electric distribution grid they have become a necessity (Weckesser et al. 2021).

In this context, the optimal exploitation strategy is further changing and adaptable during the time of the day and through the seasons. For example, in summer the PV output is at its maximum while in winter its contribution can become negligible. Moreover, PVs sizing can trade off between an energy surplus available in summer and an insufficient share in winter, being feasible by key performance indices that balance between generation and loads (Cielo et al. 2021). Similarly, the role of seasonal adaptations to better evaluate the grid impact, minimum and maximum voltage magnitudes observed within the Energy Community (EC) in the simulated weeks-timeplan were extracted, as well as maximum LV line, MV line, and MV/LV transformer loading were investigated by Weckesser et al. (2021).

With the increasing use of RES in power systems, it is also necessary to overcome the limitations of these resources in terms of the supply and demand balance in high-voltage power systems (Jo et al. 2021). In this study, the Customer-owned Energy Storage Systems (CES) was considered, defined as a market model to a scheduling problem. Such an aggregated-CES (ACES) market model was structured as a bilateral contract for fixed payments. This ACES model was designed to change the charged/discharged power of the depending on the SOC. The numerical outcomes of the proposed model revealed the reduction of the MG operator-owned large-scale ESS (LESS) capacity by enabling the consideration of the CES in the microgrid operation (Jo et al. 2021).

Beyond the aforesaid regulatory and legislation aspects, RECs offer the economic incentives for the evaluation of the business models of the REC initiative (Cielo et al. 2021). REC, as a legal entity, aggregates different users sharing their own resources to reduce both electricity bills and CO emissions. REC was deployed as a multi-objective battery sizing optimisation for renewable energy communities with distribution-level constraints, from the prosumer-driven perspective (Secchi et al. 2021). As a consequence, local public sites, such as municipalities, should be in favor of the REC and can support a feasibility study considering the use of part of the municipal buildings roofs (e.g., school, gymnasium and town hall) for hosting PVs (Cielo et al. 2021).

The electrical loads of municipal sites can be estimated on the basis of monthly electrical bills of the municipal loads, and hourly profiles can be obtained by similar standard loads. Similar to this profile, the household loads can be estimated (Cielo et al. 2021). However, in system modeling, the energy supply system that contains three energy storage methods, heat, electricity, and gas storage, is rarely considered. In the process, of modeling, few kinds of literature consider uncertainties on both the source-side and load-side. It is challenging to study an operation mode in a complex energy supply system (especially one containing HES) (Z. Liu et al. 2021).

The economic dimension is also an adhering consideration of all ECs, especially when the environmental dimension becomes widely discussed in alignment with climate changes’ mitigation and adaptation. In this context, there is a rich literature concerning those two dimensions of sustainability: environmental and economic (Kyriakopoulos 2021; Streimikiene et al. 2021). It can be also signified that the social dimension is still underrepresented. Indeed, the majority of research studies on assessing energy performance or energy projects that deal with economic or environmental sustainability, without engaging the social inclusion, which is considered a misleading dimension of sustainability (Kluczek and Gladysz 2022). Although social sustainability is the research objective of few studies, incorporation of social and energy sustainability might be a sufficient precondition for a complex energy assessment (Kluczek and Gladysz 2022). In such a study the individually setting goals by EC end-users are related to self-sufficiency, using distributed artificial intelligence and optimization, stating that individual economic goals can negatively impacting on ECs’ self-sufficiency (Weckesser et al. 2021).

Within energy circularity indicators (e.g., fossil energy use, total energy use, and CO2 emission), complementary impact indicators such as waste, materials, pollutants, and toxic emissions might be included. These indicators could be defined to support an effective and sustainable use of energy, thus, leading energy efficiency improvement, energy consumption reduction, and production costs lowering. Such a multi-targeted effect could further minimize climate change in compliance with SDGs (Kluczek and Gladysz 2022). Therefore, research challenges could be referred to (Kluczek and Gladysz 2022):

- -

- The plethora of methods to determine the evaluation framework concerns a wide range of different, occasionally competitive, indicators and measurement units of environmental, economic, and social interest (Kluczek and Gladysz 2022):

- Results visualization in terms of graphical objects designed to represent the performance of the three aforesaid indicators: environmental, economic, and social.

- Sustainability valuation regarding the individual energy-side, in alignment with sustainability criteria. Alternatively, an overall criterion should be based on a score regarding the worst/the best energy performance;

- Trade-off between the sustainability dimensions can be prevented in order to provide equal importance that is plausible for an environmental evaluation.

- -

- Constraints and barriers of applying a feasible energy sustainable performance method could be defined as follows (Kluczek and Gladysz 2022):

- Boundaries overcoming. Such boundaries are raised from an inadequate design or from a segmented implementation of policies’ planned within institutions;

- Lacking of access to data. These data are related to energy planning and they are proven beneficiary inflows of the method applied.

The aforementioned review study revealed that the main limitation of the ECs, at least in a theoretical-research viewpoint, is their decentralized attributes, having also wide geographical dispersion and covering broad energy-problem solutions, which imply different energy-planning priorities and ECs strategies of deployment to be drawn. The aforementioned research limitation is further making difficult for energy planners to develop proper ECs that are suitable as “all-in” energy solutions for all energy-consuming sectors. For instance, ECs have been commonly designed for specific energy-consuming sectors, such as at meeting household or industrial energy needs, but not for both sectors. In this respect, the emerging research question that was approached in this review study is to understand the logic behind the ECs development as well as to find ways and procedures—not necessarily technological but also procedural, regulatory, and legislative—under which these detached and decentralized ECs could be flexible, synergistic, easily adaptable, adjustable, and shift-transferable from one community to another community, in order to better serve their scoping as solutions to energy poverty, energy safety, energy autonomy and energy alleviation.

For this, the most common and of utmost importance features of all current and future ECs research are those of (a) behind-the-meter energy storage systems and (b) national energy strategic plans which are able to: (a) ensure optimal sizing and operation and (b) improve reliability in local electricity grids. However, relevant research cannot undermine the impact on the power system per se. Indeed, the lack and the constraints of technologically based knowledge commonly refer to (a) comparative research for operational strategies in economics terms (economics dimension), but also (b) investigate the concurring effects of these strategies on distribution grids (technological dimension) (Weckesser et al. 2021). Subsequently, future research should integrate ECs in such a way that can be technologically synergistic and symbiotic while, at the same time, they can be easily adaptable when selected by national energy planners worldwide. Such flexible and transferable ECs can also prioritize the joint functions: being both economic-profitable strategies and technically shifting solutions to support the smooth operation of local energy grids. Otherwise, stressing, instead of relieving, the grid can be at stake/risky. Moreover, future studies should focus on the importance between smart communities and the capability of adapting and adjusting all their (smart communities’) components at stable and reliable power supply systems, not compromising power quality.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, HES-DES is feasible and reliable to provide multiple energy sources for users. The two-layer collaborative optimization method is suitable for the collaborative optimization design of complex energy systems with HES and multiple renewable energy utilization technologies. The thermodynamic performance and comprehensive benefits analysis method in this paper are also applicable to other energy systems (J. Liu et al. 2021a, 2021b; Z. Liu et al. 2021).

Regarding the REC, these communities can be flexibly considered totally virtual, meaning that all sources and loads are connected to different points of delivery on the grid. In this way, all produced and consumed energy travels on the grid and there is no direct local consumption. Subsequently, all REC-derived revenues have to be shared within EC members on the basis of REC instate phase. In addition to to REC-granted incentives on the energy performance of the REC, another national incentive was introduced to reduce the Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) costs (Cielo et al. 2021). RECs development is also a forecasting and evaluation tool of renewable energy loads of production considering short and long term variations of ECs characteristics. RECs are of paramount importance optimization procedure coupled with real-time energy management (Cielo et al. 2021).

The contribution of this review study is the organization of the wide plethora of ECs-published studies within the last decade of analysis into representative groups of analysis. These groups reflect on the key-determinants of ECs from a research point of view, revealing the multidimensional, geographically dispersed, sectorally scattered, environmentally alarming, and socio-economically sensitive appreciation of energy, regionally and globally. Future research studies should adapt the socio-economic considerations of the future energy provision, confronting energy poverty and directing the energy future at RES-based technologies of low carbon environmental footprint and technologically feasible scale of real world (transferring model approaches in reality) conditions of applicability. In this context, there should be required the development of real-time operation methods and improving proposed ACES (Jo et al. 2021). Future research can also make identifiable the (energy) system sizes and the renewables-infrastructure dispatch strategy from building owners, while minimizing the life cycle cost of energy (Cielo et al. 2021). In implementing such EC solutions and making them easily adaptable for industrialized pilot RECs, the following issues can be considered:

- High specificity of regulation, primarily referring to refund and incentive schemes (Cielo et al. 2021).

- Flexibility of different stakeholders presence in the ECs (Cielo et al. 2021).

- Environmental and social benefits can be further investigated by ECs, along with the already developed research on the economic advantages/dimension (Cielo et al. 2021).

Current EC development is primarily regional-specific (mainly) in European countries. Plentiful initiatives on ECs have been proposed, but more studies could systematically assess the impact of ECs from different perspectives. Future studies could address different impacts if different strategies are to be applied. It is indicatively noted that studies can be used by both policy makers and Distribution System Operators (DSO), showing that slight alteration of incentives offered to ECs can cause significantly different outcomes. Thus, DSOs and policy makers can further use the research findings to create an inclusive framework for ECs that already anticipates the development and impact on the distribution grid (Weckesser et al. 2021). Selected issues of imperative significance emerging at future agendas and multi-criteria approaches are the following (Kluczek and Gladysz 2022):

- -

- Extending the available dataset towards analyzing different numbers of criteria and alternatives, followed by the reproduction of the same assessment for biodigester.

- -

- Similar experimental sessions should be applied using various MCDA methods to gain comparative analysis.

- -

- Considering the MCDA methodology on energy sustainability valuation, future research should focus on those specific uncertainties that consider the various types of biodigesters or similar projects based on biomass/bioresources to obtain reliable results and simultaneously ensuring decision-making design and energy strategic planning at a better and fully informed manner.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdalla, Ahmed, Saber Mohamed, Scott Bucking, and James S. Cotton. 2021. Modeling of thermal energy sharing in integrated energy communities with micro-thermal networks. Energy and Buildings 248: 111170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaton, Clement, Jesus Contreras-Ocana, Philippine de Radigues, Thomas Doring, and Frederic Tounquet. 2020. Energy Communities: From European Law to Numerical Modeling. Paper presented at the 17th International Conference on The European Energy Market, Stockholm, Sweden, September 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Azarova, Valeriya, Jed Cohen, Christina Friedl, and Johannes Reichl. 2019. Designing local renewable energy communities to increase social acceptance: Evidence from a choice experiment in Austria, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland. Energy Policy 132: 1176–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backe, Stian, Magnus Korpås, and Asgeir Tomasgard. 2021. Heat and electric vehicle flexibility in the European power system: A case study of Norwegian energy communities. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems 125: 106479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backe, Stian, Sebastian Zwickl-Bernhard, Daniel Schwabeneder, Hans Auer, Magnus Korpås, and Asgeir Tomasgard. 2022. Impact of energy communities on the European electricity and heating system decarbonization pathway: Comparing local and global flexibility responses. Applied Energy 323: 119470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beridze, Tamuna. 2021. The contracting state’s role in the energy community to build the European Union’s envisioned sustainable future. In Globalization, Environmental Law, and Sustainable Development in the Global South: Challenges for Implementation. London: Routledge, pp. 199–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, Giovanni, Barbara Bonvini, Stefano Bracco, Federico Delfino, Paola Laiolo, and Giorgio Piazza. 2021. Key performance indicators for an energy community based on sustainable technologies. Sustainability 13: 8789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, Saveria Olga Murielle, Martina Massari, Danila Longo, Beatrice Turillazzi, and Carlo Alberto Nucci. 2021. Designing collaborative energy communities: A european overview. Energies 14: 8226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braeuer, Fritz, Max Kleinebrahm, Elias Naber, Fabian Scheller, and Russell McKenna. 2022. Optimal system design for energy communities in multi-family buildings: The case of the German Tenant Electricity Law. Applied Energy 305: 117884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgio, Alessandro, Debora Cilio, Ilda Maria Coniglio, Anna Pinnarelli, Giorgio Graditi, and Maria Valenti. 2020. Social acceptability and market of distributed storage systems for energy communities. Paper presented at the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2020 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe, EEEIC/I and CPS Europe 2020, Madrid, Spain, June 9–12; p. 9160613. [Google Scholar]

- Buschle, Dirk, and Rozeta Karova. 2019. The EU’s sectoral communities with neighbours: The case of the energy community. In The Proliferation of Privileged Partnerships between the European Union and Its Neighbours. London: Routledge, p. 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalicchio, Valeria, Giampaolo Manzolini, Matteo Giacomo Prina, and David Moser. 2021. Optimal Allocation Method for a Fair Distribution of the Benefits in an Energy Community. Solar RRL 6: 2100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalicchio, Valeria, Giampaolo Manzolini, Matteo Giacomo Prina, and David Moser. 2022. From investment optimization to fair benefit distribution in renewable energy community modelling. Applied Energy 310: 118447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenevska, Ilina. 2010. The european parliament and the european atomic energy community: A legitimacy crisis? European Law Review 35: 415–24. [Google Scholar]

- Charokopos, Michael. 2013. Energy community and European common aviation area: Two tales of one story. European Foreign Affairs Review 18: 273–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cielo, A., P. Margiaria, P. Lazzeroni, I. Mariuzzo, and M. Repetto. 2021. Renewable Energy Communities business models under the 2020 Italian regulation. Journal of Cleaner Production 316: 128217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coignard, Jonathan, Maxime Janvier, Vincent Debusschere, Gilles Moreau, Stéphanie Chollet, and Raphaël Caire. 2021. Evaluating forecasting methods in the context of local energy communities. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems 131: 106956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coignard, Jonathan, Vincent Debusschere, Gilles Moreau, Stéphanie Chollet, and Raphaël Caire. 2020. Distributed resource coordination in the context of european energy communities. Paper presented at the IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, Virtual, August 2–6; p. 9282075. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, Giovanni, Francesco Ferrero, Giancarlo Pirani, and Andrea Vesco. 2014. Planning Local Energy Communities to develop low carbon urban and suburban areas. Paper presented at the ENERGYCON 2014—IEEE International Energy Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia, May 13–16; pp. 1012–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradie, Peter D., Olivia De Ruyck, Jelle Saldien, and Koen Ponnet. 2021. Who wants to join a renewable energy community in Flanders? Applying an extended model of Theory of Planned Behaviour to understand intent to participate. Energy Policy 151: 112121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, Francesco, Federico D’Antoni, Gianluca Natrella, and Mario Merone. 2022. A new hybrid AI optimal management method for renewable energy communities. Energy and AI 10: 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosic, Armin, Michael Stadler, Muhammad Mansoor, and Michael Zellinger. 2021. Mixed-integer linear programming based optimization strategies for renewable energy communities. Energy 237: 121559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, Juan Jose, Emad Jamil, and Barry Hayes. 2021. State of the Art in Energy Communities and Sharing Economy Concepts in the Electricity Sector. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 57: 5737–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, Felipe Barroco Fontes, Claudia Carani, Carlo Alberto Nucci, Celso Castro, Marcelo Santana Silva, and Ednildo Andrade Torres. 2021. Transitioning to a low carbon society through energy communities: Lessons learned from Brazil and Italy. Energy Research & Social Science 75: 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alpaos, Chiara, and Francesca Andreolli. 2021. Renewable energy communities: The challenge for new policy and regulatory frameworks design. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies 178: 500–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lotto, Roberto, Calogero Micciché, Elisabetta M. Venco, Angelo Bonaiti, and Riccardo De Napoli. 2022. Energy Communities: Technical, Legislative, Organizational, and Planning Features. Energies 15: 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de São José, Débora, Pedro Faria, and Zita Vale. 2021. Smart energy community: A systematic review with metanalysis. Energy Strategy Reviews 36: 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, Gerben W., Wouter PC Boon, and Alexander Peine. 2016. User-led innovation in civic energy communities. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 19: 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, Gianfranco, Sara Rotondo, Rodolfo Araneo, Giovanni Petrone, and Luigi Martirano. 2021. Innovative power-sharing model for buildings and energy communities. Renewable Energy 172: 1087–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, Beniamino, Vincenzo Bombace, Luigi Colucci Cante, Antonio Esposito, Mariangela Graziano, Gennaro Junior Pezzullo, Alberto Tofani, and Gregorio D’Agostino. 2022. Machine Learning, Big Data Analytics and Natural Language Processing Techniques with Application to Social Media Analysis for Energy Communities. Book series: Computational Intelligence in Security for Information Systems Conference CISIS 2022: Complex, Intelligent and Software Intensive Systems. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems (LNNS) 497: 425–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Silvestre, Maria Luisa, Mariano Giuseppe Ippolito, Eleonora Riva Sanseverino, Giuseppe Sciumè, and Antony Vasile. 2021. Energy self-consumers and renewable energy communities in Italy: New actors of the electric power systems. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 151: 111565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Moudene, Yassine, Jaafar Idrais, and Abderrahim Sabour. 2019. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) Use for Keywords Research Characterization. Case Study: Environment and Renewable Energy Community Interest. Paper presented at the 2019 IEEE World Conference on Complex Systems, WCCS 2019, Quarzazate, Morocco, April 22–25; p. 8930789. [Google Scholar]

- Felice, Alex, Lucija Rakocevic, Leen Peeters, Maarten Messagie, Thierry Coosemans, and Luis Ramirez Camargo. 2022. Renewable energy communities: Do they have a business case in Flanders? Applied Energy 322: 119419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fina, Bernadette, and Hubert Fechner. 2021. Transposition of European Guidelines for Energy Communities into Austrian Law: A Comparison and Discussion of Issues and Positive Aspects. Energies 14: 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fina, Bernadette, Hans Auer, and Werner Friedl. 2020. Cost-optimal economic potential of shared rooftop PV in energy communities: Evidence from Austria. Renewable Energy 152: 217–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fina, Bernadette, Miriam Schwebler, and Carolin Monsberger. 2022. Different Technologies’ Impacts on the Economic Viability, Energy Flows and Emissions of Energy Communities. Sustainability 14: 4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioriti, Davide, Andrea Baccioli, Gianluca Pasini, Aldo Bischi, Francesco Migliarini, Davide Poli, and Lorenzo Ferrari. 2021a. LNG regasification and electricity production for port energy communities: Economic profitability and thermodynamic performance. Energy Conversion and Management 238: 114128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioriti, Davide, Antonio Frangioni, and Davide Poli. 2021b. Optimal sizing of energy communities with fair revenue sharing and exit clauses: Value, role and business model of aggregators and users. Applied Energy 299: 117328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischhacker, Andreas, Georg Lettner, Daniel Schwabeneder, and Hans Auer. 2019. Portfolio optimization of energy communities to meet reductions in costs and emissions. Energy 173: 1092–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouladvand, Javanshir, Deline Verkerk, Igor Nikolic, and Amineh Ghorbani. 2022. Modelling Energy Security: The Case of Dutch Urban Energy Communities. Cham: Springer, pp. 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieden, Dorian, Andreas Tuerk, Ana Rita Antunes, Vasilakis Athanasios, Alexandros-Georgios Chronis, Stanislas d’Herbemont, Mislav Kirac, Rita Marouço, Camilla Neumann, Esteban Pastor Catalayud, and et al. 2021. Are we on the right track? Collective self-consumption and energy communities in the European Union. Sustainability 13: 12494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmsiri, Shahryar, Seama Koohi-Fayegh, Marc A. Rosen, and Gordon Rymal Smith. 2016. Integration of transportation energy processes with a net zero energy community using captured waste hydrogen from electrochemical plants. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 41: 8337–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjorgievski, Vladimir Z., Snezana Cundeva, and George E. Georghiou. 2021. Social arrangements, technical designs and impacts of energy communities: A review. Renewable Energy 169: 1138–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, Nicholas, and Pierluigi Mancarella. 2019. Flexibility in Multi-Energy Communities With Electrical and Thermal Storage: A Stochastic, Robust Approach for Multi-Service Demand Response. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 10: 503–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grignani, Anna, Michela Gozzellino, Alessandro Sciullo, and Dario Padovan. 2021. Community cooperative: A new legal form for enhancing social capital for the development of renewable energy communities in Italy. Energies 14: 7029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]