To Trust or Not to Trust? COVID-19 Facemasks in China–Europe Relations: Lessons from France and the United Kingdom

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Critical Juncture

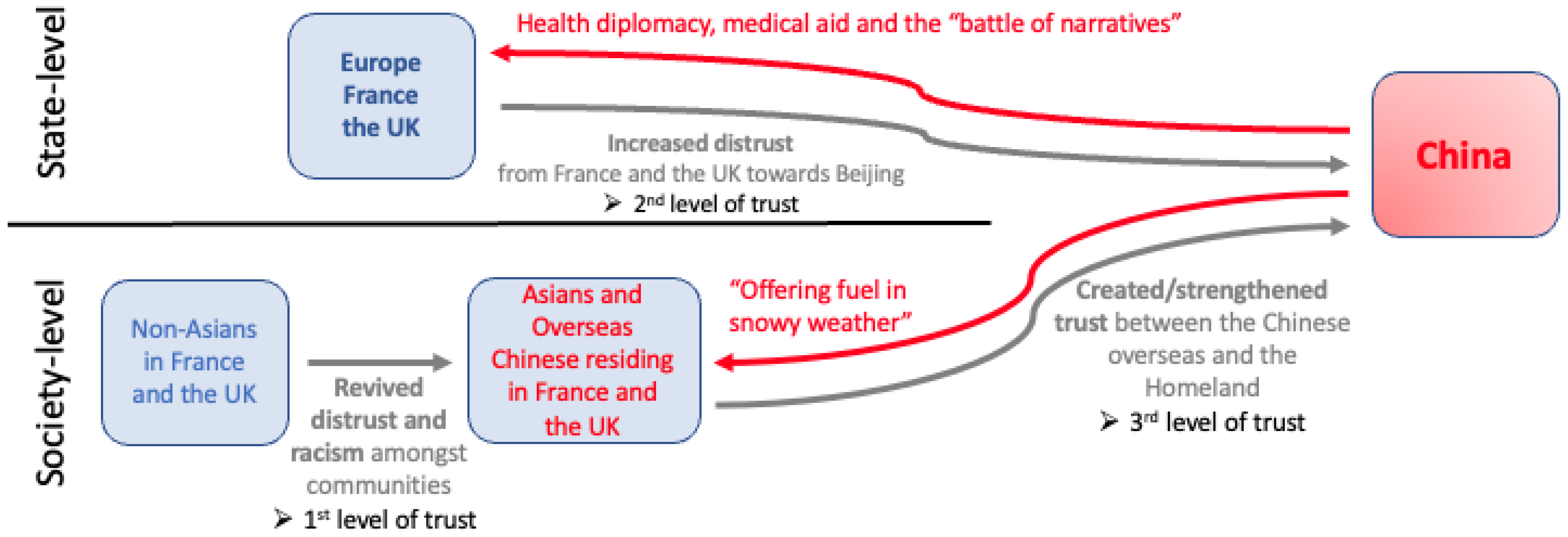

2.2. Trust

3. Materials and Research Methods

- (i)

- Chinese and European governmental statements, press conferences, and announcements from 2018 to April 2020.

- (ii)

- Chinese, French, and British media reports and web contents from January to April 2020, including but not limited to The Global Times, Xinhua, Le Monde, Le Figaro, The Guardian, CGTN, France Television, LCI, and the BBC.

- (iii)

- Posts on social media and discussion forums from December 2019 to May 2020.

- (iv)

- A total of 21 in-depth interviews with overseas Chinese in Europe, conducted in March–April–May 2020.

4. Findings

4.1. Antecedent Conditions: Unfulfilled Expectations and Growing Distrust in China–Europe Pre-Pandemic Relations

4.2. Cleavage: Solidarity from Europe to China

4.3. Critical Juncture: The Battle of Narratives

Since the Republic of Korea, Japan and Singapore, which are Asian democracies, are succeeding in controlling the epidemic, why are old democracies like Europe and the United States not succeeding?[…]Asian countries, including China, have been particularly successful in their fight against COVID-19 because they have that sense of community and civility that Western democracies lack.

4.4. Production of the Legacy: “Offering Fuel in the Snowy Weather” from the Chinese State to the Diaspora

4.5. Legacy: To Wear or Not to Wear? The Mask Dilemma and Racism

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The frame analysis of British and French media was made possible thanks to the research project titled China’s Twitter Diplomacy: Content and Impact, funded by Aarhus University Research Foundation—AUFF NOVA, and led by Dr Mette Thunø and in which the two authors are Co-Investigators. |

| 2 | The Twitter data and analysis derive from the above research project. |

References

- Ambassade de Chine en France (@AmbassadeChine). 2020. Twitter. March 27 6:04 P.M.. Available online: https://twitter.com/AmbassadeChine/status/1243584778319933440?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1243584778319933440%7Ctwgr%5E%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.leparisien.fr%2Fpolitique%2Fl-ambassadeur-de-chine-a-paris-convoque-pour-ses-propos-sur-le-coronavirus-14-04-2020-8299737.php (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Ambassade de la République Populaire de Chine en République Française. 2020. Déclaration du Porte-parole de l’Ambassade de Chine en France sur certains propos d’un article publié par l’Ambassade qui ont été déformés par la presse [Statement by the Spokesperson of the Chinese Embassy in France on Certain Remarks of an Article Published by the Embassy Which Were Distorted by the Press]. Available online: http://www.amb-chine.fr/fra/zfzj/t1772378.htm (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Association des Jeunes Chinois de France. 2020. La crise du COVID-19 en France: Position et Actions de l’AJCF. Available online: https://www.lajcf.fr/la-crise-du-COVID-19-en-france-position-et-actions-de-lajcf/ (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Axelrod, Robert. 1990. The Evolution of Cooperation. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- BBC News. 2020. Coronavirus: Countries Reject Chinese-Made Equipment. March 30. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-52092395 (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Booth, Ken, and Nicholas Wheeler. 2010. The Security Dilemma: Fear, Cooperation and Trust in World Politic. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Börzel, Tanja A. 2015. The noble west and the dirty rest? Western democracy promoters and illiberal regional powers. Democratization 22: 519–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brady, Anne-Marie. 2017. Magic Weapons: China’s Political Influence Activities under Xi Jinping. Washington: Wilson Center, September, Available online: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/magic-weapons-chinas-political-influence-activities-under-xi-jinping (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Brand, Laurie. 2008. Citizens Abroad: Emigration and the State in the Middle East and North Africa. Edited by Paperback. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carothers, Thomas, and Marina Ottaway. 2010. Uncharted Journey: Promoting Democracy in the Middle East. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. [Google Scholar]

- CGTN. 2020a. China Thanks EU Donations to Assist Relief Efforts during Coronavirus Outbreak. February 1. Available online: https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-02-01/China-s-Li-EU-s-von-der-Leyen-discuss-coronavirus-outbreak-over-phone-NJg1gNIx7q/index.html (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- CGTN. 2020b. Chinese President Xi Jinping Holds Phone Talks with World Leaders over COVID-19. March 24. Available online: https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-03-24/Xi-Only-by-working-together-can-mankind-win-battle-against-COVID-19-P70OtcZl4Y/index.html (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Chan, Steve. 2017. Trust and Distrust in Sino-American Relations: Challenge and Opportunity. Amherst: Cambria Press. [Google Scholar]

- China United Front News Network. 2020. Guonei sheqiao jigou fenfen xiang haiwai juan zhang fangyi wuzi [Domestic Overseas Chinese Institutions Have Donated Materials for Epidemic Prevention to Overseas]. Available online: http://tyzx.people.cn/BIG5/n1/2020/0415/c431923-31673976.html (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Chinese Students and Scholars Association UK. 2020. Shouqianshou xinlianxin—Shandong zhuanjia zhuli liuying xuezi beibuqu he beiaiqu kangyi jishi. [Hand in Hand, Heart to Heart—Shandong Experts Help Chinese Students Studying in the UK to Fight the Epidemic in Northern England and Northern IRELAND], July 31. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/w-MGs4F6zmc18rX4hBtWsQ (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Chuang, Ya-Han, Émilie Tran, and Hélène le Bail. 2021. From Silence to Action: The Chinese in France. Global Dialogue. Magazine of the International Sociological Association 11. Available online: https://globaldialogue.isa-sociology.org/articles/from-silence-to-action-the-chinese-in-france (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Cole, Alister, Julien S. Baker, and Dionysios Stivas. 2021. Trust, Transparency and Transnational Lessons from COVID-19. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, David, and Gerardo L. Munck. 2017. Building Blocks and Methodological Challenges: A Framework for Studying Critical Junctures. Qualitative and Multi-Method Research 15: 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, Larry, and Orville Schell. 2019. China’s Influence and American Interest: Promoting Constructive Vigilance. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Economy, Elizabeth. 2018. Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2016. Future of Europe. In Special Eurobarometer 451. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/dataset/S2131_86_1_451_ENG (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- European Commission. 2018. Joint Communication to the European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee, The Committee of the Regions and the European Investment Bank. Connecting Europe and Asia—Building blocks for an EU Strategy. Available online: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/joint_communication_-_connecting_europe_and_asia_-_building_blocks_for_an_eu_strategy_2018-09-19.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- European Commission. 2019. EU-China-A Strategic Outlook. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/communication-eu-china-a-strategic-outlook.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- European Commission. 2020. President Ursula Von der Leyen on Her Phone Call with the Prime Minister of China LI Keqiang. Available online: https://audiovisual.ec.europa.eu/en/topnews/M-004589 (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- European Parliament, Directorate-General for Internal Policies. 2018. The New Silk Route—Opportunities and Challenges for EU Transport. p. 15. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/585907/IPOL_STU(2018)585907_EN.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- France24. 2019. Discours d’Emmanuel Macron, Xi Jinping, Angela Merkel et Jean-Claude Juncker à l’Elysée. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FWd55m2n_0g (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Fukuyama, Francis. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Global Times. 2020. Available online: https://twitter.com/globaltimesnews/status/1243074378704678918 (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Goffman, Erving. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. New York: Harper Torchbooks. [Google Scholar]

- Grierson, Jamie. 2020. Anti-Asian Hate Crimes up 21% in UK during Coronavirus Crisis. The Guardian. May 13. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/13/anti-asian-hate-crimes-up-21-in-uk-during-coronavirus-crisis (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Hamilton, Clive. 2018. Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia. Melbourne: Hardie Grant Books. [Google Scholar]

- Harnisch, Sebastian, Sebastian Bersick, and Jörn-Carsten Gottwald. 2015. China’s International Roles: Challenging or Supporting International Order? London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hine, Christine. 2015. Ethnography for the Internet: Embedded, Embodied and Everyday. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, An Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, Aaron M. 2002. A Conceptualization of Trust in International Relations. European Journal of International Relations 8: 375–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Human Rights Watch. 2020. Country Chapters: China’s Global Threat to Human Rights. World Report 2020. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/global (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- Hvistendahl, Mara. 2020. The Scientist and the Spy: A True Story of China, the FBI, and Industrial Espionage. New York: Riverhead Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Xi. 2020. Chinese in the UK Donate $396,000 to Help Wuhan’s Doctors Fighting Coronavirus. CGTN. Februaary 1. Available online: https://newseu.cgtn.com/news/2020-02-01/Chinese-in-the-UK-donate-396-000-to-help-Wuhan-s-doctors-NIcscNjxjG/index.html (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Kowalski, Bartosz. 2021. China’s Mask Diplomacy in Europe: Seeking Foreign Gratitude and Domestic Stability. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 50: 209–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kydd, Andrew. 2005. Trust and Mistrust in International Relations. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LCI. 2020. L’ambassade de Chine plaide le piratage après la publication d’un dessin polémique sur Twitter. [Chinese Embassy Pleads Hacking after Controversial Cartoon Posted on Twitter. May 25. Available online: https://www.lci.fr/international/tensions-etats-unis-chine-l-ambassade-chinoise-plaide-le-piratage-apres-la-publication-d-un-dessin-polemique-sur-twitter-2154696.html (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Le Monde. 2020. L’ambassadeur de Chine à Paris convoqué pour «certains propos» liés au coronavirus. [Chinese Ambassador to Paris Summoned for “Certain Remarks” Related to the Coronavirus]. February 15. Available online: https://www.lemonde.fr/sante/article/2020/04/15/l-ambassadeur-de-chine-a-paris-convoque-pour-certains-propos-lies-au-coronavirus_6036610_1651302.html (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Leach, William, and Paul Sabatier. 2005. To trust an adversary: Integrating rational and psychological models of collaborative policymaking. American Political Science Review 99: 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lieberthal, Kenneth, and Jisi Wang. 2012. Addressing U.S.-China Strategic Distrust. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/0330_china_lieberthal.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Lipset, Seymour M., and Stein Rokkan, eds. 1967. Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments: An Introduction. In Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York: Free Press, pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lulu, Jichang. 2019. Repurposing Democracy: The European Parliament China Friendship Cluster. Sinopsis. November 26. Available online: https://sinopsis.cz/en/ep/ (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- McGillivray, Fiona, and Alastair Smith. 2000. Trust and cooperation through agent-specific punishments. International Organization 54: 809–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mercer, David. 2020. Coronavirus: Hate Crimes against Chinese People Soar in UK during COVID-19 Crisis. Skynews. Available online: https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-hate-crimes-against-chinese-people-soar-in-uk-during-COVID-19-crisis-11979388 (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Murphy, Simon. 2020. Chinese People in UK Targeted with Abuse over Coronavirus. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/18/chinese-people-uk-targeted-racist-abuse-over-coronavirus-southampton (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Oushinet. 2020. Yingguo huaqiao huaren qixin zhuli wuhan “kangyi” [Overseas Chinese in the UK Work Together to Help Wuhan in the “Fight against the Epidemic”]. Available online: http://www.oushinet.com/wap/qj/qjnews/20200202/340069.html (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Pak, Anton, Emma Mcbryde, and Oyelola A. Adegboye. 2021. Does High Public Trust Amplify Compliance with Stringent COVID-19 Government Health Guidelines? A Multi-country Analysis Using Data from 102, 627 Individuals. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 1: 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- People’s Daily. 2020. “Jiankang sichou zhilu” wei shengming huhang—kangji yiqing libukai mingyun gongtongti yishi [The “Health Silk Road” Escorts Life—The Fight against the Epidemic Is Inseparable from the Community of Common Destiny]. Available online: http://theory.people.com.cn/n1/2020/0324/c40531-31645276.html (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Phillips, Tom. 2017. EU Backs Away from Trade Statement in Blow to China’s ‘Modern Silk Road’ Plan. The Guardian. May 15. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/may/15/eu-china-summit-bejing-xi-jinping-belt-and-road (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Qi, Jingwen, Stijn Joye, and Stijn Van Leuven. 2021. Framing China’s mask diplomacy in Europe during the early covid-19 pandemic: Seeking and contesting legitimacy through foreign medical aid amidst soft power promotion. Chinese Journal of Communication, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolf, Moritz, and Stiftung Wissenschaft Und Politik. 2021. ‘China’s Health Diplomacy during Covid-19: The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Action. SWP Comment. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzicka, Jan, and Nicholas Wheeler. 2010. The puzzle of trusting relationships in the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. International Affairs 86: 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saechang, Orachorn, Jianxing Yu, and Yong Li. 2021. Public Trust and Policy Compliance during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Professional Trust. Healthcare 9: 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaman, John, and French Institute of International Relations (IFRI). 2020. COVID-19 and Europe-China Relations: A Country-Level Analysis. Available online: https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/etnc_special_report_covid-19_china_europe_2020.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Silver, Laura, Kat Devlin, and Christine Huang. 2020. Unfavorable Views of China Reach Historic Highs in Many Countries—Majorities Say China Has Handled COVID-19 Outbreak Poorly. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/10/06/unfavorable-views-of-china-reach-historic-highs-in-many-countries/ (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Silver, Laura, Kat Devlin, and Christine Huang. 2021. Large Majorities Say China Does Not Respect the Personal Freedoms of Its People. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2021/06/30/large-majorities-say-china-does-not-respect-the-personal-freedoms-of-its-people/ (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Sohu. 2020. Yingguo henan tongxianghui qiaobao wei jiaxiang juanzeng kang”yi”wu [Overseas Chinese from the Henan Association of the United Kingdom Donated Anti-Epidemic Materials to Their Hometown]. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/371160088_160386 (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Statista. 2021. Level of Trust in Government in China from 2016 to 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1116013/china-trust-in-government-2020/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Statista. 2022. Selected Countries with the Largest Number of Overseas Chinese 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/279530/countries-with-the-largest-number-of-overseas-chinese/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. 2020a. Wang yi: Jianjue daying kangyi yiqing zujizhan tuidong goujian renlei mingyun gongtongti [Wang Yi: Resolutely win the Fight against the Epidemic and Promote the Building of a Community with Shared Future for Mankind]. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/guowuyuan/2020-03/01/content_5485253.htm (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. 2020b. Zhonggong zhongyang zhengzhi ju changwu weiyuanhui zhaokai huiyi yanjiu jiaqiang xinxing guanzhuang bingdu ganran de feiyan yiqing fangkong gongzuo xijinping zhuchi huiyi [The Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee Held a Meeting to Study and Strenghten the Prevention and Control of the Pneumonia Epidemic That Is Caused by the New Coronavirus Infection, the Meeting Was Chaired by Xi Jinping]. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-02/03/content_5474309.htm (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- The White House. 2017. The National Security Strategy of the United States. December. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905-2.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Thunø, Mette. 2018. China’s New Global Position: Changing Policies towards the Chinese Diaspora in the 21st Century. In China’s Rise and the Chinese Overseas, 1st ed. Edited by Bernard and Tan Chee-Beng Wong. London: Routledge, pp. 184–208. [Google Scholar]

- Thunø, Mette. 2021. Panel 9: Twitter Diplomacy. Hong Kong Baptist University. YouTube. November 12. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fF7w_NXjybY (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Thunø, Mette. 2022. Chinese Twitter. Aarhus University Centre for Humanities Computing. Available online: https://github.com/centre-for-humanities-computing/chinese-twitter (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Tianjin Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese. 2020. Qing jiaxiang renmin shouxia women de xinyi!—Yingguo tianjin shanghui juanzeng wuzi qiyun [We Ask Our People to Receive Our Kind Regards—The UK-China Business Association Sends Out Donation Shipments]. Available online: http://www.tjql.org.cn/system/2020/02/09/020023050.shtml (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Torsten, Michel. 2016. ‘Trust and International Relations’. Oxford Bibliographies. Available online: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199743292/obo-9780199743292-0192.xml (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Tran, Emilie, and Ya-Han Chuang. 2019. Social Relays of China’s Power Projection? Overseas Chinese Collective Actions for Security in France. International Migration 58: 101–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Emilie, and Yahia H. Zoubir. 2022. Introduction to the Special Issue China in the Mediterranean: An Arena of Strategic Competition? Mediterranean Politics, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Emilie. 2022. Role dynamics and trust in France-China coopetition. Mediterranean Politics, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of State. 2020. Communist China and the Free World’s Future. In Speech by Michael R. Pompeo, Secretary of State. Available online: https://cl.usembassy.gov/secretary-michael-r-pompeo-remarks-communist-china-and-the-free-worlds-future/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Uslaner, Eric M. 2002. The Moral Foundations of Trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jisi. 2019. Assessing the radical transformation of U.S. policy toward China. China International Strategy Review 1: 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Wicks, Andrew C., Shawn L. Berman, and Thomas M. Jones. 1999. The Structure of Optimal Trust: Moral and Strategic Implications. The Academy of Management Review 24: 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinhua. 2020a. Shandong fuying lianhe gongzuozu wancheng renwu huiguo [The Shandong Joint Working Group to Britain Completes Its Mission and Returns to China]. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020-04/03/c_1125811960.htm (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Xinhua. 2020b. Xi Says China’s Battle against COVID-19 Making Visible Progress. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-02/19/c_138797580.htm (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Xinhua. 2020c. Xinhua Headlines: China Returns Solidarity with Europe in COVID-19 Battle. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-03/20/c_138898996.htm (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Zhao, Huanxin. 2020. US Sending Experts to Fight Virus. China Daily. January 30. Available online: https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202001/30/WS5e324e46a310128217273b07.html (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Zhao, Lijian. 2020. 2020 nian 4 yue 10 ri wai jiao bu fa yan ren zhao li jian zhu chi li xing ji zhe hui [Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian’s Regular Press Conference on 10 April 2020—Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Kingdom of Belgium]. Available online: http://be.chineseembassy.org/chn/fyrth/t1768268.htm (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Zhao, Suisheng. 2022. The US–China Rivalry in the Emerging Bipolar World: Hostility, Alignment, and Power Balance. Journal of Contemporary China 31: 169–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoubir, Yahia H., and Emilie Tran. 2021. China’s Health Silk Road in the Middle East and North Africa Amidst COVID-19 and a Contested World Order. Journal of Contemporary China, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tran, E.; Tseng, Y.-c. To Trust or Not to Trust? COVID-19 Facemasks in China–Europe Relations: Lessons from France and the United Kingdom. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2022, 15, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15040187

Tran E, Tseng Y-c. To Trust or Not to Trust? COVID-19 Facemasks in China–Europe Relations: Lessons from France and the United Kingdom. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2022; 15(4):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15040187

Chicago/Turabian StyleTran, Emilie, and Yu-chin Tseng. 2022. "To Trust or Not to Trust? COVID-19 Facemasks in China–Europe Relations: Lessons from France and the United Kingdom" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15, no. 4: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15040187

APA StyleTran, E., & Tseng, Y.-c. (2022). To Trust or Not to Trust? COVID-19 Facemasks in China–Europe Relations: Lessons from France and the United Kingdom. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(4), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15040187