Risk Management in the Internationalization of Small and Medium-Sized Spanish Companies

Abstract

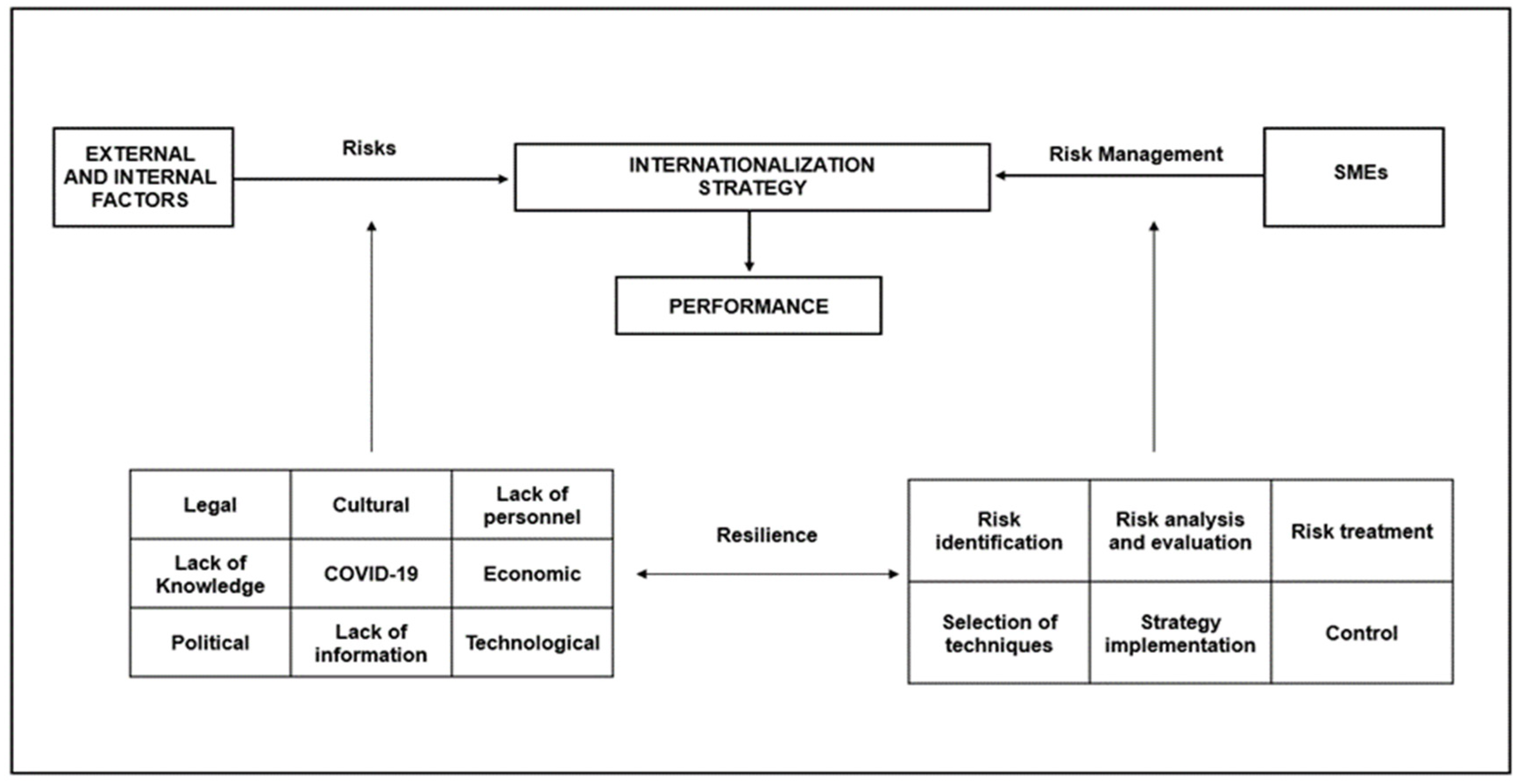

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Internationalization of Spanish SMEs Analysis

2.2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Literature Review

3.2. Method Selection

3.3. Case Selection

3.4. Data Collection

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Identification of Risks

“If money is collected in other currency and a currency devaluation occurs, profitability is compromised. Therefore, currency devaluations jointly with currency instability have a great impact on my business”.

“If we see that a country is unstable, but there is a customer potential that we see clearly, it is pulled forward. There are times when you must take risks. I can tell you about countries in the Middle East that maybe shock you and with which we are working. There is a political risk, but we consider the potential or progression that the client has had and we decide to go forward. It does not have so much to do with the country’s risk, which is also considered, but with the client itself. If, the country is a bit politically or economically conflictive but we see potential customers, we bet on it”.

“We want to start our process of expansion to United States but believing that the model of Europe or Spain can work in the United States is a mistake and we have to change things due to cultural differences. As a result, cultural adaptation is needed to succeed”.

“Our company is financially healthy, so we have had no problem with respect to COVID-19. I imagine that other firms which were not achieving high records in periods before the pandemic have more difficulties to survive than a company which have been financially healthy”.

“Our activity is very specific, so everything was based on visits to clients and attendance at technical fairs and specialists in the sector. For example, there were events that were there without being held for two years, so this activity is really noticeable for our company”.

4.2. Risk Management Systems

“Given the cultural differences, we use the issue of certifications to a great extent. For example, if we sell to Arab countries, we need Halal certificates. In the past, these certifications were associated with religion, but now the consumer interpret these certifications as quality certifications. There are also markets, such as Israel or the US, where some products need the Kosher certificate. For example, in Turkey, we need a Halal certificate and not just any type of Halal certificate, since we need one that is recognized by the country where we are going to sell our product”.

“The analysis of the region is given to me by the distributor; but in the countries where I sell more extensively, the local salesperson is the one that performed an analysis of the country for me. We also have traders who provide us with an analysis of the country, but we do not pay much attention to them since their knowledge is via telephone and we do not trust much of the information given by telephone. The most valid information is from the one who is in the country, and in 100% of the cases, we go to the ground and verify what they told us”.

“For international sales we have promoted a lot through digital marketing. So, in the past, it was sold by visiting clients, which was a face-to-face activity. Now, it is more through social networks, Google, or search engines. Keep in mind that our niche market is very specific, so we really are one of the 3 largest manufacturers in Europe. If you position yourself well, it is not difficult, but you must know how to position yourself”.

4.3. Differentiation Strategy

“We try to give to the product an added value or other properties that are not found on the market. If you have an element of technological differentiation, it is easier than if you do not have it. If you do not have one, you must fight with the same weapons as all other competitors and you must look for other different weapons to differentiate you, such as price, advertising/marketing, etc. That is why one of the main criteria for internationalization is innovation. The brand image in Spain is a differentiating element that helps us”.

“There is a rapid adaptation to the client’s needs. For us, that is essential, since it is a differentiating point with respect to other competitors. We adapt very quickly to market situations, and I think it is essential since we have the ideal size for that flexibility, that many larger companies cannot have. For us, on the one hand, it is an advantage, but a disadvantage on the other, as we must adapt to each one’s situation”.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Research Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andres, Beatriz, Raul Poler, and Eduardo Guzman. 2022. The Influence of Collaboration on Enterprises Internationalization Process. Sustainability 14: 2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Wensong, Christine Holmström-Lind, and Martin Johanson. 2018. Leveraging networks, capabilities and opportunities for international success: A study on returnee entrepreneurial ventures. Scandinavian Journal of Management 34: 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajo, Javier, María L. Borrajo, Juan F. De Paz, Juan M. Corchado, and María A. Pellicer. 2012. A multi-agent system for web-based risk management in small and medium business. Expert Systems with Applications 39: 6921–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldauf, Artur, David W. Cravens, and Udo Wagner. 2000. Examining determinants of export performance in small open economies. Journal of World Business 35: 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, Javier, Ana C. González, Juan M. Ramón, and Raquel Flórez. 2022. Impact of COVID-19 on the Internationalisation of the Spanish Agri-Food Sector. Foods 11: 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank of Spain. 2021. La Economía Española: Impacto de la Pandemia y Perspectivas. Available online: https://www.bde.es/f/webbde/GAP/Secciones/SalaPrensa/IntervencionesPublicas/DirectoresGenerales/economia/Arc/Fic/arce260521.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Bell, Judith. 2005. Doing Your Research Project. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Brustbauer, Johannes K. 2016. Enterprise risk management in SMEs: Towards a structural model. International Small Business Journal 34: 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, Peter J. 1989. Foreign direct investment by small-and medium-sized enterprises: The theoretical background. Small Business Economics 1: 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, Peter J. 2016. The contribution of internalisation theory to international business: New realities and unanswered questions. Journal of World Business 51: 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullough, Amanda, and Maija Renko. 2013. Entrepreneurial resilience during challenging times. Business Horizons 56: 343–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusgil, S. Tamer, and Gary Knight. 2015. The born global firm: An entrepreneurial and capabilities perspective on early and rapid internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies 46: 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrato, Daniele, and Mariacristina Piva. 2012. The internationalization of small and medium-sized enterprises: The effect of family management, human capital and foreign ownership. Journal of Management and Governance 16: 617–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CESGAR. 2021. X Informe “La Financiación de la PYME en España”. Resultados del primer semestre de 2021. Available online: http://www.cesgar.es/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/X-Informe-financiaci%C3%B3n-de-la-pyme.-Resultados-2021.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Chamber of Commerce. 2021. Impacto Económico de la COVID-19 sobre la PYME en España. Available online: https://www.camara.es/sites/default/files/publicaciones/informe_pyme_2021._impacto_economico_de_la_covid-19_sobre_la_pyme_en_espana.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Child, John, and Suzana B. Rodrigues. 2011. How organizations engage with external complexity: A political action perspective. Organization Studies 32: 803–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinco Días. 2021. La COVID-19 y sus efectos económicos en las pymes españolas. Available online: https://cincodias.elpais.com/cincodias/2021/06/28/pyme/1624873056_800554.html (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Clealand, Jennifer A. 2017. The qualitative orientation in medical education research. Korean Journal Medical Education 29: 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabic, Marina, Jane Maley, Leo-Paul Dana, Ivan Novak, Massimiliano M. Pellegrini, and Andrea Caputo. 2019. Pathways of SME internationalization: A bibliometric and systematic review. Small Business Economics 55: 705–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, Dirk, Harry J. Sapienza, R. Isil Yavuz, and Lianxi Zhou. 2012. Learning and knowledge in early internationalization research: Past accomplishments and future directions. Journal of Business Venturing 27: 143–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, Gerry. 2001. Enterprise risk management: Its origins and conceptual foundation. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance 26: 360–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, Noémie, and Ulrike Mayrhofer. 2017. Internationalization stages of traditional SMEs: Increasing, decreasing and re-increasing commitment to foreign markets. International Business Review 26: 1051–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, Fabian. 2020. Masters of disasters? Challenges and opportunities for SMEs in times of crisis. Journal of Business Research 116: 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2021. Annual Report on European SMEs 2020/2021. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira de Araújo Lima, Priscila, María Crema, and Chiara Verbano. 2020. Risk management in SMEs: A systematic literature review and future directions. European Management Journal 38: 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foli, Samuel, Susanne Durst, Lidia Davies, and Serdal Temel. 2022. Supply Chain Risk Management in Young and Mature SMEs. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, John, Glenn R. Carroll, and Michael T. Hannan. 1983. The liability of newness: Age dependence in organizational death rates. American Sociological Review 48: 692–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freixanet, Joan, Alex Rialp, and Iya Churakova. 2020. How do innovation, internationalization, and organizational learning interact and co-evolve in small firms? a complex systems approach. Journal of Small Business Management 58: 1030–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigo, Mark L., and Richard J. Anderson. 2011. Strategic risk management: A foundation for improving enterprise risk management and governance. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance 22: 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdeano-Gómez, Emilio, Juan C. Pérez-Mesa, and José A. Aznar-Sánchez. 2016. Internationalisation of Smes and Simultaneous Strategies of Cooperation and Competition: An Exploratory Analysis. Journal Business of Economics Management 17: 1114–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerring, John. 2004. What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for? The American Political Science Review 98: 341–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, Audrey, David Carson, and Aodheen O’Donnell. 2004. Small business owner-managers and their attitude to risk. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 22: 349–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, Denny. 2021. A systematic methodology for doing qualitative research. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 57: 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Conde, Jacobo, and Ernesto López-Valeiras. 2017. The dual role of management accounting and control systems in exports: Drivers and payoffs. Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting 47: 307–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Spain. 2021. Plan de Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia. Componente 13. Impulso a la PYME. Available online: https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/temas/fondos-recuperacion/Documents/30042021-Plan_Recuperacion_%20Transformacion_%20Resiliencia.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Guili, Hamza, and Driss Ferhane. 2018. Internationalization of SMEs and Effectuation: The Way Back and Forward. Proceedings 2: 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmersson, Mikael. 2014. Small and medium-sized enterprise internationalisation strategy and performance in times of market turbulence. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 32: 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisrich, Robert, Michael Peters, and Dean Shepherd. 2017. Entrepreneurship, 10th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Hollman, Kenneth W., and S. Mohammad-Zadeh. 1984. Risk management in small business. Journal of Small Business Management 22: 7–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Young Jun, and Nicholas S. Vonortas. 2014. Managing risk in the formative years: Evidence from young enterprises in Europe. Technovation 34: 454–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Gary A., and Peter W. Liesch. 2016. Internationalization: From incremental to born global. Journal of World Business 51: 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, Andrew. 2007. Intellectual Capital Management as Part of Knowledge Management Initiatives at Institutions of Higher Learning. Journal of Knowledge Management 5: 181–92. [Google Scholar]

- Laufs, Katharina, and Christian Schwens. 2014. Foreign market entry mode choice of small and medium-sized enterprises: A systematic review and future research agenda. International Business Review 23: 1109–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Hoang B. H., Thi L. Nguyen, Chi T. Ngo, Thi B. T. Pham, and Thi B. Le. 2020. Policy related factors affecting the survival and development of SMEs in the context of COVID 19 pandemic. Management Science Letters 10: 3683–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, Ralph, Christian Hauser, and Rico Baldegger. 2013. Managing Export Risks: Export Risk Management Guidelines. Zürich: Switzerland Global Enterprise. [Google Scholar]

- Leonidou, Leonidas C. 1995. Empirical research on export barriers: Review, assessment, and synthesis. Journal of International Marketing 3: 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Jane W., and Paul W. Beamish. 2001. The internationalization and performance of SMEs. Strategic Management Journal 22: 565–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majocchi, Antonio, and Antonella Zucchella. 2003. Internationalization and Performance: Findings from a Set of Italian SME. International Small Business Journal 21: 249–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merly, Corinne, Antony Chapman, and Christophe Mouvet. 2011. An End-Users Oriented Methodology for Enhancing the Integration of Knowledge on Soil–Water-Sediment Systems in River Basin Management: An Illustration from the AquaTerra Project. Environmental management 49: 111–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikes, Anette. 2011. From counting risk to making risk count: Boundary-work in risk management. Accounting, Organizations and Society 36: 226–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism. 2021a. Cifras PYME. Datos a Diciembre de 2021. Available online: http://www.ipyme.org/Publicaciones/CifrasPYME-diciembre2021.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism. 2021b. Estructura y Dinámica Empresarial en España. Available online: http://www.ipyme.org/es-ES/Paginas/Home.aspx (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Oparaocha, Gospel Onyema. 2015. SMEs and international entrepreneurship: An institutional network perspective. International Business Review 24: 861–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviatt, Benjamin M., and Patricia Phillips McDougall. 1994. Toward a theory of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies 25: 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Justin. 2020. SCOPE framework for SMEs: A new theoretical lens for success and internationalization. European Management Journal 38: 219–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Luis, Alexandra Ternera, Joao Bispo, and Joao Wemans. 2015. A risk diagnosing methodology web-based platform for micro, small and medium business: Remarks and enhancements. Communications in Computer and Information Science 454: 340–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, Michael E. 1985. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. Hong Kong: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reymen, Isabelle M. M. J., Petra Andries, Hans Berends, Rene Mauer, Ute Stephan, and Elco Van Burg. 2015. Understanding dynamics of strategic decision-making in venture creation: A process study of effectuation and causation. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 9: 351–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rialp, Alex, and Josep Rialp. 2001. Conceptual frameworks on SMEs’ internationalization: Past, present and future trends of research. Advances in International Marketing 11: 49–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribau, Cláudia P., António Carrizo Moreira, and Mário Raposo. 2018. SME internationalization research: Mapping the state of the art. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences 35: 280–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, Mark, Philip Lewis, and Adrian Thornhill. 2009. Research Methods for Business Students, 5th ed. Harlow: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Vanninen, Heini, Joona Keränen, and Olli Kuivalainen. 2022. Becoming a small multinational enterprise: Four multinationalization strategies for SMEs. International Business Review 31: 101917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbano, Chiara, and Karen Venturini. 2013. Managing Risks in SMEs: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation 8: 186–97. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, Karl E., and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe. 2006. Mindfulness and the Quality of Organizational Attention. Organization Science 7: 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, XiaoChi, Lars Kuchinke, Marcella L. Would, Julia Velten, and Jürgen Margraf. 2017. Survey method matters: Online/offline questionnaires and face-to-face or telephone interviews differ. Computers in Human Behavior 71: 172–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Structure of the Interview | Sample of Questions Used |

|---|---|

| Personal and company information | Which are your key responsibilities in this company? Which are the key factors for your company now? |

| Internationalization | Which was the decisive factor to decide internationalizing? Did the company experiment any change due to the internationalization process? How is international activity coordinated and managed? |

| Risks | What are the specific risks that SMEs must face in the internationalization process? How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected your company? How is the company influenced by environmental factors? |

| Management Risks | How does your company manage international risks? |

| Business Strategy | Which strategy have you used to internationalize? |

| Category | Position | Duration of the Interview | Activity | Year of Foundation | Internationalization Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interview #1 | Export Manager | 42:54:19 | Oil | 1978 | From the beginning |

| Interview #2 | Chief Executive Officer | 27:20:50 | Transport | 2000 | From the beginning |

| Interview #3 | Export Manager | 25:04:60 | Gummed Paper | 1998 | From the beginning |

| Interview #4 | Chief Financial Officer | 29:25:60 | Fertilizers | 2003 | Since COVID-19 |

| Interview #5 | Chief Executive Officer | 34:39:19 | Sulphur, Fertilizers | 2004 | Since COVID-19 |

| Interview #6 | Export Manager | 28:15:60 | Almonds | 1980 | From the beginning |

| Interview #7 | Chief Executive Officer | 26:58:80 | Marmalade | 2005 | Since COVID-19 |

| Interview #8 | Chief Executive Officer | 27:36:50 | Textile | 2012 | Since COVID-19 |

| Interview #9 | Export Manager | 27:14:28 | Packaging | 2000 | Since Spanish financial crisis 2008 |

| Interview #10 | Chief Commercial Officer | 24:13:30 | Strawberry | 1999 | From the beginning |

| Interview #11 | Chief Executive Officer | 22:35:70 | Yogurt | 2014 | From the beginning |

| Interview #12 | Chief Financial Officer | 28:55:80 | Technology | 2019 | Since COVID-19 |

| Interview #13 | Export Manager | 24:27:60 | Containers | 2015 | From the beginning |

| Interview #14 | Chief Commercial Officer | 29:45:80 | Gardening | 2015 | Since COVID-19 |

| Interview #15 | Chief Commercial Officer | 33:28:20 | Machinery | 2005 | From the beginning |

| Interview #16 | Chief Commercial Officer | 36:24:91 | Pre-harvest and post-harvest products for food industry | 2000 | Since COVID-19 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González Calzadilla, A.C.; Segovia Villarreal, M.; Ramón Jerónimo, J.M.; Flórez López, R. Risk Management in the Internationalization of Small and Medium-Sized Spanish Companies. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2022, 15, 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080361

González Calzadilla AC, Segovia Villarreal M, Ramón Jerónimo JM, Flórez López R. Risk Management in the Internationalization of Small and Medium-Sized Spanish Companies. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2022; 15(8):361. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080361

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález Calzadilla, Ana Cruz, María Segovia Villarreal, Juan Manuel Ramón Jerónimo, and Raquel Flórez López. 2022. "Risk Management in the Internationalization of Small and Medium-Sized Spanish Companies" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15, no. 8: 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080361

APA StyleGonzález Calzadilla, A. C., Segovia Villarreal, M., Ramón Jerónimo, J. M., & Flórez López, R. (2022). Risk Management in the Internationalization of Small and Medium-Sized Spanish Companies. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(8), 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15080361