Tracing the Optimal Level of Political and Social Change under Risks and Uncertainties: Some Lessons from Ancient Sparta and Athens

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Nexus between Financial and Sociopolitical Risks: A Review

3. Defining Further Political and Social Change in Democratic Regimes

4. Sparta: The Structure of Political and Economic Institutions

4.1. Political Institutions

4.2. Economic Institutions

5. Evaluation of Sparta’s Political and Social System

5.1. Rigidity in Managing Geopolitics and Internal Political Affairs

5.2. Failure to Adapt to New Trends in Military Organization

5.3. Failure to Establish a Series of Necessary Socioeconomic Changes

5.4. A Comprehensive Assessment of the Socioeconomic and Political System of Sparta

6. Athens: An Adaptable Society with Collective Decision-Making Procedures

6.1. The Political Structure

6.2. The Economy

7. Reducing Systemic Risks When Institutional and Political Change Occurs: Athens during the 4th Century

“Even though the nomothetai gave final approval to the laws in the fourth century, it was the Assembly that initiated all laws and submitted them to the nomothetai. Their authority derived from the citizens of Athens, which is why they were called the laws of the Athenians (not the laws of the nomothetai).”

8. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | A notion that derives from financial economics. |

| 2 | Due to space limitations, we cannot retrieve all of this bibliography here, but only a representative part of it. |

| 3 | The term refers to the so-called Delian League or Athenian Alliance of the 478–404 period. It was an association/military alliance of more than 300 Greek city-states, under the leadership of Athens, whose initial purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire. Gradually, Athens acquired a hegemonic role within it. For a financial aspect regarding the functioning of the Alliance, see Figueira and Jensen (2021). |

| 4 | Neodamodeis (new citizens) were given citizenship whenever the state deemed it necessary, mainly, we guess, when the city needed to replenish the ranks of the citizens after severe manpower losses, such as after the earthquake of about 461 BCE, the losses from the Peloponnesian War, and the crushing defeats of the Spartan army by the Thebans and Boeotians in 371 and 362 BCE. |

| 5 | Only Athenian male citizens enjoyed full political rights. Slaves, metics (citizens that came to Athens from other city-states for work) and women were excluded from political participation. |

| 6 | See, among others, Cohen (1992), Ober (2008), Halkos and Kyriazis (2010), Lyttkens (2013), Bergh and Lyttkens (2014), Bitros et al. (2020), Economou et al. (2021a, 2021b), Halkos et al. (2021, 2022) and the references cited therein. |

| 7 | One talent was equal to 6000 drachmae. As a measure of comparison, the daily wage of an unskilled worker during the 4th century BCE was 1.5 drachmae. |

| 8 | Due to space limitations, we cannot retrieve all this evidence here, but a detailed analysis of such legal and judicial procedures is provided by Schwartzberg (2004), Harris (2013), Lyttkens et al. (2018) and Canevaro (2018), among others. |

| 9 | They were members of the nine archons, an ex-aristocratic body. |

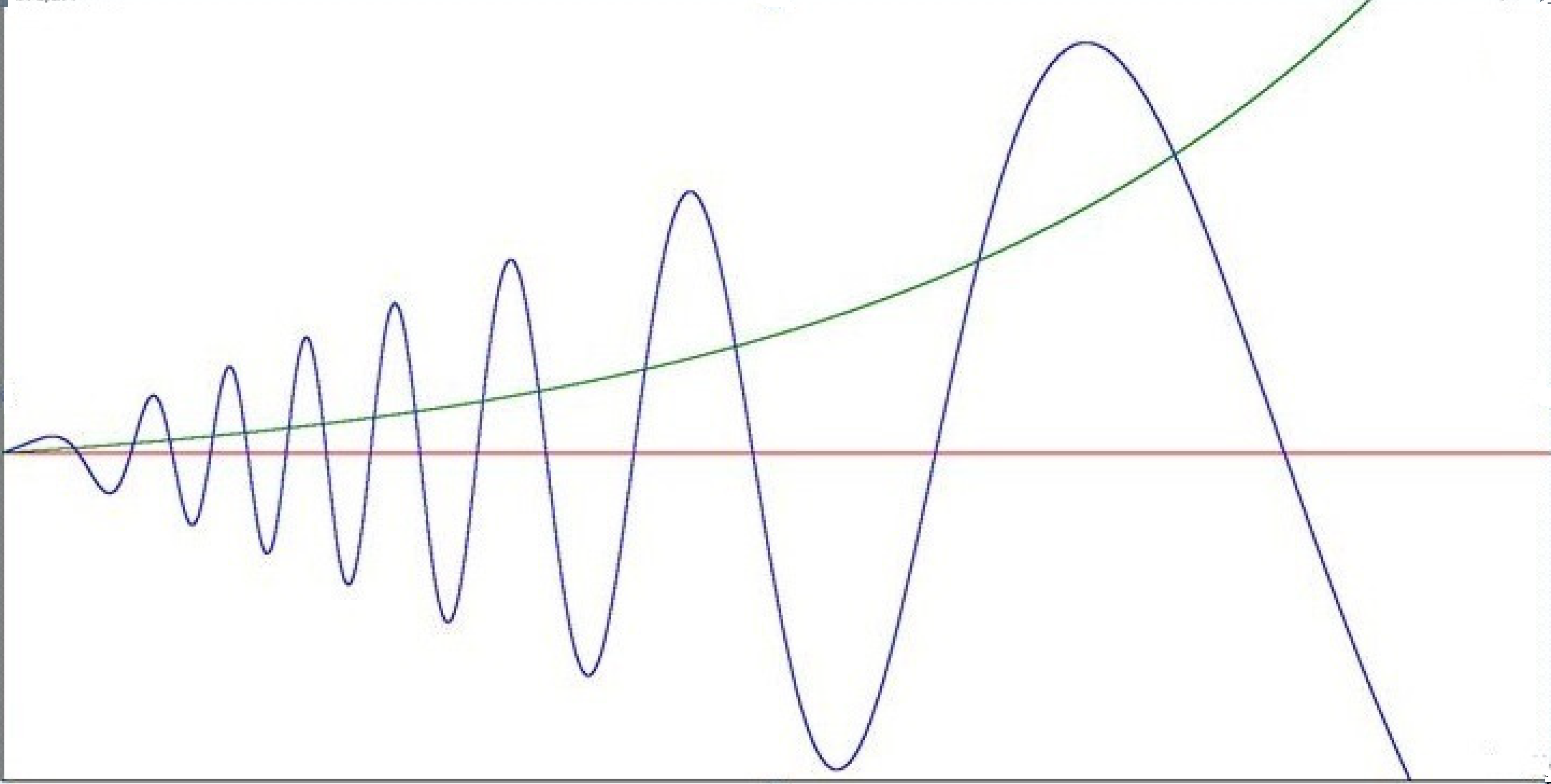

| 10 |

References

- Acemoglu, Daron, and James Robinson. 2013. Why Nations Fail. New York: Crown Business. [Google Scholar]

- Achen, Christopher H. 2022. The Crisis of Democracy: A Self-Inflicted Wound. In Democracy in Times of Crises Challenges, Problems and Policy Proposals. Edited by Emmanouil M. L. Economou, Nicholas C. Kyriazis and Athanasios Platias. Cham: Switzerland, pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, Alberto, and Roberto Perotti. 1996. Income distribution, political instability, and investment. European Economic Review 40: 1203–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, Alberto, Sule Ozler, Nouriel Roubini, and Philip Swagel. 1992. Political Instability and Economic Growth. NBER Working Paper, No. 4173. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle. 1944. Politics, vol. 21, Engl. Trnsl. H. Rackham. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. London: William Heinemann Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Barro, Robert J. 1991. A Cross-country Study of Growth, Saving, and Government. In National Saving and Economic Performance. Edited by B. Douglas Bernheim and John B. Shoven. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 271–304. [Google Scholar]

- Bekaert, Geert, Campbell R. Harvey, Christian T. Lundblad, and Stephan Siegel. 2014. Political risk spreads. Journal of International Business Studies 45: 471–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, Andreas, and Carl Hampus Lyttkens. 2014. Measuring institutional quality in Ancient Athens. Journal of Institutional Economics 10: 279–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitros, Geprge C., Emmanouil M. L. Economou, and Nicholas C. Kyriazis. 2020. Democracy and Money: Lessons for Today from Athens in Classical Times. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, James, and Gordon Tullock. 1962. The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caldara, Dario, and Mateo Iacoviello. 2022. Measuring geopolitical risk. American Economic Review 112: 1194–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canevaro, Mirko. 2018. What was the law of Leptines’ really about? Reflections on Athenian public economy and legislation in the fourth century BCE. Constitutional Political Economy 29: 440–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartledge, Paul. 1987. Agesilaos and the Crisis of Sparta. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cartledge, Paul. 2001. Sparta and Laconia. A Regional History, 1300–362 BC. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cartledge, Paul. 2018. Democracy: A Life, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cartledge, Paul. 2022. Greece’s Finest Hour? The Democratic Implications of the Battle of Salamis. In Democracy and Salamis. 2500 Years After the Battle that Saved Greece And the Western World. Edited by Emmanouil M. L. Economou, Nicholas C. Kyriazis and Athanasios Platias. Cham: Springer, pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cartledge, Paul, and Anthony Spawforth. 2002. Sparta and Lakonia. A Regional History 1300–362 BC. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Charfeddine, Lanouar, and Hisham Al Refai. 2019. Political tensions, stock market dependence and volatility spillover: Evidence from the recent intra-GCC crises. North American Journal of Economics and Finance 50: 101032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Edward E. 1992. Athenian Economy and Society: A Banking perspective. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, Michael H., and David Whitehead. 1983. Archaic and Classical Greece. A Selection of Ancient Sources. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Delios, Andrew, and Witold J. Henisz. 2003. Political hazards, experience, and sequential entry strategies: The international expansion of Japanese firms, 1980–1998. Strategic Management Journal 24: 1153–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, Emmanouil Μ. L. 2020. The Achaean Federation in Ancient Greece: History, Political and Economic Organisation, Warfare and Strategy. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Economou, Emmanouil Μ. L., and Nicholas C. Kyriazis. 2016. Choosing peace against war strategy. A history from the ancient Athenian democracy. Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy 22: 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, Emmanouil Μ. L., and Nicholas C. Kyriazis. 2019. Democracy and Economy: An Inseparable Relationship Since Ancient Times to Today. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Economou, Emmanouil M. L., and Nikolaos A. Kyriazis. 2021. Spillovers between Russia’s and Turkey’s geopolitical risk During the 2000–2021 Putin administration. Peace Economics, Peace Sciense and Public Policy 28: 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, Emmanouil M. L., Nicholas C. Kyriazis, and Loukas Zachilas. 2016. Interpreting Sociopolitical Change by Using Chaos Theory: A Lesson from Sparta and Athens. MPRA Paper No. 76117. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/76117/ (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Economou, Emmanouil-Marios L., Nicholas C. Kyriazis, and Nikolaos A. Kyriazis. 2021a. Money decentralization under direct democracy procedures. The case of Classical Athens. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, Emmanouil M. L., Nikolaos A. Kyriazis, and Nicholas C. Kyriazis. 2021b. Managing financial risk while performing international commercial transactions. Intertemporal lessons from Athens in Classical times. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, Emmanouil M. L., Nicholas C. Kyriazis, and Athanasios Platias, eds. 2022. Democracy and Salamis. 2500 Years After the Battle that Saved Greece And the Western World. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Faccio, Mara, Ronald W. Masulis, and John J. McConnell. 2006. Political connections and corporate bailouts. The Journal of Finance 61: 2597–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, Thomas J., and Sean R. Jensen. 2021. Hegemonic Finances. Funding Athenian Domination in the 5th Centuries BC. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck, Robert K., and F. Andrew Hanssen. 2006. The origins of democracy: A model with application to Ancient Greece. Journal of Law and Economics XLIX: 115–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagarin, Michael. 2013. Laws and Legislation in Ancient Greece. In A Companion to Ancient Greek Government. Edited by Hans Beck. Malden: Willey-Blackwell, pp. 221–34. [Google Scholar]

- Geithner, Timothy. F. 2014. Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crises. New York: Crown Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou, Miltiades, Nicholas C. Kyriazis, and Emmanouil M. L. Economou. 2015. Democracy, Political Stability and Economic performance. A panel data Analysis. Journal of Risk & Control 2: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gorlizki, Yoram, and Oleg Khlevniuk. 2020. Substate Dictatorship: Networks, Loyalty, and Institutional Change in the Soviet Union. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, Gene M., and Elhanan Helpman. 1991. Innovation and Growth in the Global Economy. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Habicht, Christian. 1999. Athens from Alexander to Anthony. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halkos, George E., and Nicholas C. Kyriazis. 2010. The Athenian economy in the age of Demosthenes: Path dependence and change. European Journal of Law and Economics 29: 255–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, George E., Nicholas C. Kyriazis, and Emmanouil M. L. Economou. 2021. Plato as a game theorist towards an international trade policy. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, George E., Emmanouil M. L. Economou, and Nicholas C. Kyriazis. 2022. Environmental economics in Classical Athens. Journal of Institutional Economics, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Edward D. 2013. The Rule of Law in Action in Democratic Athens. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henisz, Witold J., and Andrew Delios. 2001. Uncertainty, imitation, and plant location: Japanese multinational corporations, 1990–1996. Administrative Science Quarterly 46: 443–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, Geoffrey M. 2022. On the Limits of Democracy. In Democracy in Times of Crises Challenges, Problems and Policy Proposals. Edited by Emmanouil M. L. Economou, Nicholas C. Kyriazis and Athanasios Platias. Cham: Springer Nature, pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hodkinson, Stephen. 2009. Property and Wealth in Classical Sparta. Swansea: Classical Press of Wales. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, Donald, and Gregory F. Viggiano. 2013. Men of Bronze: Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella, Stephan, and Noah D. Rubins. 2005. International Investment, Political Risk and Dispute Resolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirikkaleli, Dervis. 2020. Does political risk matter for economic and financial risks in Venezuela? Economic Structures 9: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornai, Janos. 1990. The Road to a Free Economy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznets, Simon. 1966. Modern Economic Growth: Rate, Structure, and Spread. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriazis, Nikolaos A., and Emmanouil M. L. Economou. 2021. The Impacts of geopolitical uncertainty on turkish lira during the Erdoğan administration. Defence and Peace Economics 33: 731–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazis, Nicholas C., and Michel Zouboulakis. 2004. Democracy, sea power and institutional change: An economic analysis of the Athenian Naval Law. European Journal of Law and Economics 17: 117–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyttkens, Carl Hampus. 2013. Economic Analysis of Institutional Change in Ancient Greece. Politics, Taxation and Rational Behaviour. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lyttkens, Carl Hampus, George Tridimas, and Anna Lindgren. 2018. Making direct democracy work: A rational-actor perspective on the grapheparanomon in ancient Athens. Constitutional Political Economy 29: 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, Douglass C. 1981. Structure and Change in Economic History. New York: W.W. Norton and Company. [Google Scholar]

- North, Douglass C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- North, Douglass C. 1991. Institutions. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 5: 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ober, Josiah. 2008. Democracy and Knowledge. Innovation and Learning in Classical Athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ober, Josiah. 2017. Demopolis: Democracy before Liberalism in Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ober, Josiah. 2022. Herodotus on Rationality and Cooperation Before Salamis. In Democracy and Salamis. 2500 Years After the Battle that Saved Greece And the Western World. Edited by Emmanouil M. L. Economou, Nicholas C. Kyriazis and Athanasios Platias. Cham: Springer Verlag, pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rahe, Paul A. 2016. The Spartan Regime. Its Character, Origins, and Grand Strategy. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, Paul J. 2007. The Greek City States: A Source Book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrik, Dani. 2000. Institutions for high-quality growth: What they are and how to acquire them. Studies in Comparative International Development 35: 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, Dani. 2007. One Economics. Many Recipes. Globalization, Institutions and Economic Growth. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzberg, Melissa. 2004. Athenian democracy and legal change. American Political Science Review 98: 311–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. 1993. The role of the state in financial markets. The World Bank Economic Review 7: 19–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassam, Aftab H., Shujahat H. Hashmi, and Faiz U. Rehman. 2016. Nexus between political instability and economic growth in Pakistan. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 230: 325–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toynbee, Arnold J. 1951. A Study of History. Vol. 4, Breakdowns of Civilizations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, Dung Viet, M. Kabir Hassan, Ahmed W. Alam, Luca Pezzo, and Mariani Abdul-Majid. 2021. Economic policy uncertainty, agency problem, and funding structure: Evidence from US banking industry. Research in International Business and Finance 58: 101470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlenbruck, Klaus, Peter Rodriguez, Jonathan Doh, and Lorraine Eden. 2006. The impact of corruption on entry strategy: Evidence from telecommunications projects in emerging economies. Organization Science 17: 402–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Huiqiang. 2019. The causality link between political risk and stock prices: A counterfactual study in an emerging market. Journal of Financial Economic Policy 11: 338–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingast, Barry. 1993. Constitutions as governance structures: The political foundations of secure markets. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics 149: 286–311. [Google Scholar]

| Financial Risk (FR) and Political Risk (PR) | Bibliographical References |

|---|---|

| PR negatively affects financial markets | (Stiglitz 1993) |

| A strong nexus between PR, economic risks and FR in general | (Alesina et al. 1992; Alesina and Perotti 1996; Georgiou et al. 2015; Kirikkaleli 2020) |

| A strong nexus between PR and economic governance | (North 1990; Weingast 1993; Uhlenbruck et al. 2006) |

| A strong nexus between PR and the financial sector in general | (Bekaert et al. 2014) |

| PR negatively affects firms’ profitability and survivability | (Faccio et al. 2006; Tran et al. 2021) |

| PR negatively affects investments | (Barro 1991; Kinsella and Rubins 2005; Tabassam et al. 2016) |

| PR negatively affects the stock market | (Charfeddine and Al Refai 2019; Wang 2019) |

| PR discourages multinational companies from entering a market | (Henisz and Delios 2001; Delios and Henisz 2003; Uhlenbruck et al. 2006) |

| Geopolitical risks, which are directly related to PR, affect the financial sector and markets | (Caldara and Iacoviello 2022; Economou and Kyriazis 2021; Kyriazis and Economou 2021) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Halkos, G.E.; Economou, E.M.L.; Kyriazis, N.C. Tracing the Optimal Level of Political and Social Change under Risks and Uncertainties: Some Lessons from Ancient Sparta and Athens. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2022, 15, 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15090416

Halkos GE, Economou EML, Kyriazis NC. Tracing the Optimal Level of Political and Social Change under Risks and Uncertainties: Some Lessons from Ancient Sparta and Athens. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2022; 15(9):416. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15090416

Chicago/Turabian StyleHalkos, George E., Emmanouil M. L. Economou, and Nicholas C. Kyriazis. 2022. "Tracing the Optimal Level of Political and Social Change under Risks and Uncertainties: Some Lessons from Ancient Sparta and Athens" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15, no. 9: 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15090416

APA StyleHalkos, G. E., Economou, E. M. L., & Kyriazis, N. C. (2022). Tracing the Optimal Level of Political and Social Change under Risks and Uncertainties: Some Lessons from Ancient Sparta and Athens. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(9), 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15090416