Abstract

The purpose of this study is to consider the events leading to the development of modern accounting standards for Islamic banks and, thereafter, to consider the accounting process and related impact on the financial statements for the Murabaha contract. A qualitative review of the available literature was conducted to meet this purpose. First, the influence of culture on accounting is considered, and after that, the historical development of Islamic accounting is explored. Next, the modern development in Islamic accounting is explained. The discussion then summarizes the contracts used by Islamic banks, with a particular focus on the Murabaha contract as it is the most widely used contract. The structure of the Murabaha contract is detailed, along with the criticisms found in the literature. Thereafter, the accounting treatment of the Murabaha contract is highlighted, followed by a simulation to illustrate the accounting process and its impact on the financial statements. This study contributes to the debate about the need for Islamic accounting standards as it relates to Islamic financial institutions.

1. Introduction

Culture can be understood as groups sharing similar values and perspectives not shared by other groups (Gray 1988; Hofstede 1984). Thus, when groups set up institutions, those institutions reflect the culture of the group (Hofstede 1984). Globalization has shown how different cultures around the world can have an influence on how accounting is practiced (Heidhues and Patel 2011). The way accounting is practiced can be seen as rituals that represent the culture (Haniffa and Hudaib 2002). Sulaiman and Willett (2001) argue that considering accounting practice as being objective, without considering the group’s culture, will result in the supply of information, that is not useful to the group. The provision of accounting information should reflect the social, economic, legal, and religious norms within a cultural group (Abdel Karim 1995; Abdel-Magid 1981; Dean and Clarke 2003). The religious custom within a group needs to be considered, as these cultural rituals influence accounting practice (Murtuza 2002).

The introduction of Islamic finance and, in particular, the establishment of modern Islamic banking in the 20th century, led to the belief that existing accounting frameworks were not capable of capturing Sharia (Islamic law) requirements (Askary and Clarke 1997; Haniffa and Hudaib 2007; Velayutham 2014). The Islamic bank operates according to economic principles that are derived from the Sharia and, in turn, attracts customers who are either religiously inclined or who appreciate the ethical principles followed in conducting business (Kettell 2010; Moosa 2022; Moosa and Kashiramka 2022). Some basic economic principles that render Islamic banking different from conventional banking include the prohibition of interest, profit and loss sharing, asset-backed transactions, and trading in permissible industries (Tlemsani 2010). Consequently, non-compliance with the Sharia creates an additional risk, which is not in conventional banking (Ginena 2013; Ramabulana and Moosa 2022). The emergence of Islamic accounting stems from the need to report information that takes account of Sharia requirements and other disclosures for investment account holders, hence the need for an Islamic accounting standard setter to be established (Saidani et al. 2021; Salman 2022). The Accounting and Auditing Organisation for Islamic financial institutions (AAOIFI) fulfils this purpose (Mohammed et al. 2015).

The Islamic bank uses Sharia-approved contracts to conduct business (Ismail and Tohirin 2010). The Murabaha sales contract is the most prevalent and dominant, which is an important element in the financial statements of an Islamic bank. Studies based on qualitative literature reviews have considered the accounting treatment for the Murabaha contract. For instance, Al-Sulaiti et al. (2018), found that Islamic banks in Qatar and Bahrain complied most with the Murabaha accounting standard developed by AAOIFI. Others, such as Ahmed et al. (2016), examined the accounting treatment for the Murabaha contract and its effects on the financial statements when using AAOIFI and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) accounting standards. The authors report that AAOIFI standards take the legal structure of contracts into account; hence, IFRS standards do not capture the essence of the Murabaha contract. Furthermore, the authors state that profit allocations using IFRS is based on amortised cost, while AAOIFI uses a straight-line basis. The studies mentioned above considered Financial Accounting Standard 2 (FAS 2): Murabaha and Murabaha to the Purchase Order, which has since been replaced by FAS 28: Murabaha and Other Deferred Payment Sales, effective from 1 January 2019 (Financial Accounting Standard 28 2017, para. 51). To the best of the author’s knowledge, studies have not considered the accounting treatment based on FAS 28 and its implications for financial statements. Within this backdrop, the purpose of this study is to consider the events leading to the development of modern accounting standards for Islamic banks and, thereafter, to consider the accounting process and related impact on the financial statements for the Murabaha contract. The study follows a qualitative literature review to meet this purpose by exploring the existing literature on this topic.

The following sections provide a historical account of the development of Islamic accounting. Then, the modern development of Islamic accounting is explored, followed by a discussion on the types of contracts used by the Islamic bank. An explanation of the structure of the Murabaha contract is provided, including the related criticisms and studies of the Murabaha contract found in the extant literature. The guidelines to account for the Murabaha contract based on FAS 28 are detailed and followed by a simulation to illustrate the accounting treatment and impact on the financial statements as guided by FAS 28. Finally, the study concludes with a discussion of the findings linked to the study’s purpose.

2. Historical Development of Islamic Accounting

Before establishing the Islamic State in 622AD, all business enterprise was confined to the Middle East, with Makkah as a central business hub (Zaid 2000). Thereafter, as the Islamic State expanded, particularly after the conquest of Makkah in 630AD, a need for a systematic accounting process emerged to record the receipt and disbursement of zakah, which is wealth tax payable by qualifying Muslims (Hamid et al. 1995; Zaid 2000). Hamid et al. (1995) remarks that all ancient civilizations, including the Islamic Empire, developed accounting practices due to their well-developed tax systems. As a result, the Islamic State instituted a prototype of modern banking called Baitul-Maal (house of wealth), which functioned as a financial institution. The Baitul-Maal was tasked with recording income from various sources such as zakah, the spoils of war, agricultural and food assets, and expenses such as credit disbursements or social obligations (Salman 2022).

The Islamic State under the rule of the Umayyads (661AD to 750AD) and particularly the rule of the Abbasids (750AD to 1258CE) saw the development of sophisticated record-keeping systems (Ambashe and Alrawi 2013; Salman 2022). Recorded transactions had to be both objective and verifiable and include details such as the reference number, date, place, and amount of a transaction, including the details of the payer and payee (Solas and Otar 1994). Superior budgeting systems were also used and prepared according to a geographical area under the control of the Islamic State (Salman 2022). Several accounting books were created per the type of transactions recorded, for example, general journals, stable accounting, agricultural accounting, construction accounting, treasury accounting, and currency accounting (Salman 2022; Zaid 2000). Those responsible for recording transactions during this time had to be suitably qualified by demonstrating technical competence, understanding Islamic values, and being responsible and trustworthy (Zaid 2000).

Due to the developments in accounting practice discussed in the previous paragraph, some scholars argue that the double-entry book-keeping system already existed in Muslim lands and was adopted by the Italians who popularized this method of accounting (Hamid et al. 1995; Salman 2022). Other scholars, such as Solas and Otar (1994), question the crediting of the double-entry book-keeping system to Luca Pacioli, who is considered to be the ”father of accounting” due to the accounting systems already developed in Muslim lands before Pacioli was born. The Italians required products from the Middle East; thus, Muslim traders pooled their finances to meet this growing demand. Zaid (2000) argues that through this process, the Italians learned about the accounting techniques used by Muslim traders and adopted similar naming conventions; for example, the word ”journal” is called zournal in Italian, which is a direct translation of the Arabic equivalent jaridah. Thus, there is a case to be made that the application of modern accounting practice can be traced to the accounting conventions used by the Islamic State (Hamid et al. 1995; Trokic 2015).

3. Modern Developments in Islamic Accounting

As colonial rule ended in Muslim lands toward the start of the 20th century, Muslim thinkers began to explore ways of incorporating Islamic religious practice into the everyday lives of ordinary Muslims (Hanif 2011; Jha 2013; Lica 2015). A project that brought an Islamic angle to existing knowledge was started to incorporate Islamic values into conventional Western sciences, which created the modern conceptions of Islamic economics (Gattoo and Gattoo 2017; Khan 2013). Islamic economics found its expression through Islamic banking (Kuran 1995; Sairally 2007).

The literature provides contrasting opinions on the dates when Islamic banking emerged in the 20th century. Some researchers state that its conceptual beginnings began in the 1940s (Billah 2007; Khan and Bhatti 2008). This contrasts with Nathan and Pierce (2009), who claim that an Islamic bank already existed in Palestine in 1930 called the Arab Bank of Palestine. Others, such as Roy (1991) and Tripp (2006), state that in the 1950s, an institution was founded in Pakistan to provide interest-free loans and is the first example of a modern Islamic bank. A pilgrimage fund initially referred to as the Muslim Pilgrim Savings Corporation, later known as the Tabung Haji, was established in Malaysia to invest the savings of those preparing to make the pilgrimage to Mecca. It was set up in the late 1950s and became a fully-fledged Sharia-compliant investment bank in 1962 (Kahf 1999), while others believed it to be a finance company (Aburime and Alio 2009). The consensus, however, is that Mit Ghamr Bank, established as a socially orientated institution in Egypt in 1963, is the prototype of Islamic banking in the modern era (Akacem and Gilliam 2002; Ariff 1988; Asutay 2008; Ghauri and Qambar 2012). These institutions provided an economic blueprint founded on Islamic norms and axioms and portrayed a genuine concern for the general well-being of Islamic society (Asutay 2007; Tripp 2006).

The newly acquired political independence accompanied by the oil boom in the 1970s saw a significant transfer of petrodollar wealth into Muslim oil-producing nations (Akacem and Gilliam 2002; Aldohni 2015; Mansour et al. 2015). This was the antecedent to modern commercial Islamic banking, as Orthodox Muslims from these nations sought Islamically permissible ways to invest their newfound wealth (Jawadi et al. 2016; Kazi and Halabi 2006). Investing in companies that have considerable income from interest is not allowed in the Sharia; thus, solutions to identify Sharia-compliant companies were needed (Arslan-Ayaydin et al. 2018). In 1970, 44 countries participated in the Organisation of Islamic Conference held in Saudi Arabia to clarify Islamic finance principles and discuss a model for modern Islamic banking (Tripp 2006; Warde 2012). This led to the establishment of the Islamic Development Bank in 1975, catering to member countries and principally functioning as an inter-governmental bank based on Sharia principles to fund developmental projects (Ariff 1988; Askari et al. 2009; Sairally 2007; Tripp 2006). The first commercial Islamic bank, the Dubai Islamic Bank, opened in Dubai in 1975. Thereafter, a spate of Islamic banks, such as the Faisal Islamic Bank of Sudan in 1977, the Faisal Islamic Bank of Egypt in 1977, and the Bahrain Islamic Bank in 1979, opened their doors for Sharia-compliant banking business (Aburime and Alio 2009; Ariff 1988).

In Table 1, Lica (2015) and Warde (2012) provide a timeline showing the various periods of the development of Islamic banking. The period between 1950 to 1974 can be attributed to the development of theory to support and operationalize modern Islamic banking. The period between 1974 to 1991 was a period of experimentation as the theory developed to support the industry was implemented. The period between 1991 to date saw the Islamic finance industry gaining support on a global scale, which necessitated the need for accounting standards to support the growth and standardization of the industry across jurisdictions.

Table 1.

Timeline of the Development of Islamic Banking.

The Sharia-compliant nature of the Islamic bank created a need for the development of accounting standards to reflect the Sharia-compliant contracts used in Islamic banking and to ensure that the accounting policies and annual financial statements align with Islamic law (Wahyudi et al. 2022). Existing accounting standards were not developed with Islamic banking in mind, thus reporting using existing standards failed to capture the true essence of the Islamic bank (Salman 2022; Sharair et al. 2013) To address this need, the AAOIFI was established in 1991 in Bahrain. As its primary objectives, the AAOIFI tasked itself with the responsibility of developing, harmonizing, and disseminating accounting and auditing thought, including the preparation, promulgation, interpretation, review, and amendment of accounting, auditing, and Sharia governance standards that conform with Islamic law (Vinnicombe 2012). AAOIFI has issued 100 standards of which up to 28 standards relate to guidance on various accounting issues pertinent to the Islamic bank (AAOIFI 2023). These accounting standards cater to the unique contracts used by Islamic banks (Jamaldeen 2012; Abdel Karim 2001) as conventional accounting standards such as IFRS were not developed to cater for these contracts (Nethercott and Eisenberg 2012).

4. Common Contracts Used by Islamic Banks to Conduct Business

The Islamic bank’s engine is the Sharia-approved contract (El-Gamal 2006; Abdel Karim 2001; Mirakhor and Zaidi 2007). These contracts can be sale, partnership, lease, or fee-based (Kholvadia 2017). Contracts should be undertaken for a good and beneficial purpose (Ismail and Tohirin 2010). The Sharia stipulates that being ”faithful” to contractual terms is a sacred duty (Alam et al. 2017; Kettell 2011; Shaukat et al. 2017). A contract has three elements required to establish its validity, being (1) the offer, (2) the contracting parties, both of whom have legal capacity, and (3) the subject matter that is Sharia-compliant (Ismail and Tohirin 2010; Lahsasna 2014). No ”theory of contracts” exists in Islam, only rules specified to set the tone for various transactions attached to real assets that could arise (Alam et al. 2017; Haniffa et al. 2002; Kahf 2007). These transactions can principally be categorized as either equity (variable return) or debt (fixed return) based contracts, as illustrated in Table 2 (Dar 2007; Oshodi 2014). The key features of contracts need to be understood, as this will impact the accounting treatment thereof (Nethercott and Eisenberg 2012).

Table 2.

Common Contracts used by Islamic Banks.

Partnership contracts such as mudarabah and musharakah based on profit- and loss-sharing principles and fee-based contracts such as qard-hassan represent the true spirit of Islamic banking (Lewis 2001; Nouman et al. 2018). These contracts have a solid moral and ethical focus and assist the Islamic bank in carrying out its social responsibility (Boutayeba et al. 2014; Jamaldeen 2012). In practice, however, adopting these contracts is negligible (Asutay 2008; Nouman et al. 2018, p. 22; Oshodi 2014). The debt-based modes of financing—particularly the Murabaha contract—have dominated the industry (Cebeci 2012; Dusuki and Abozaid 2007). The Murabaha contract was expected to play a subsidiary role (Warde 2012); however, it accounts for 75 to 80 percent of all Islamic banking transactions worldwide (Benamraoui 2008; Elfakhani et al. 2007), with a 90 percent utilisation in Saudi Arabia and Iran (Yanikkaya and Pabuccu 2017).

5. The Murabaha Contract

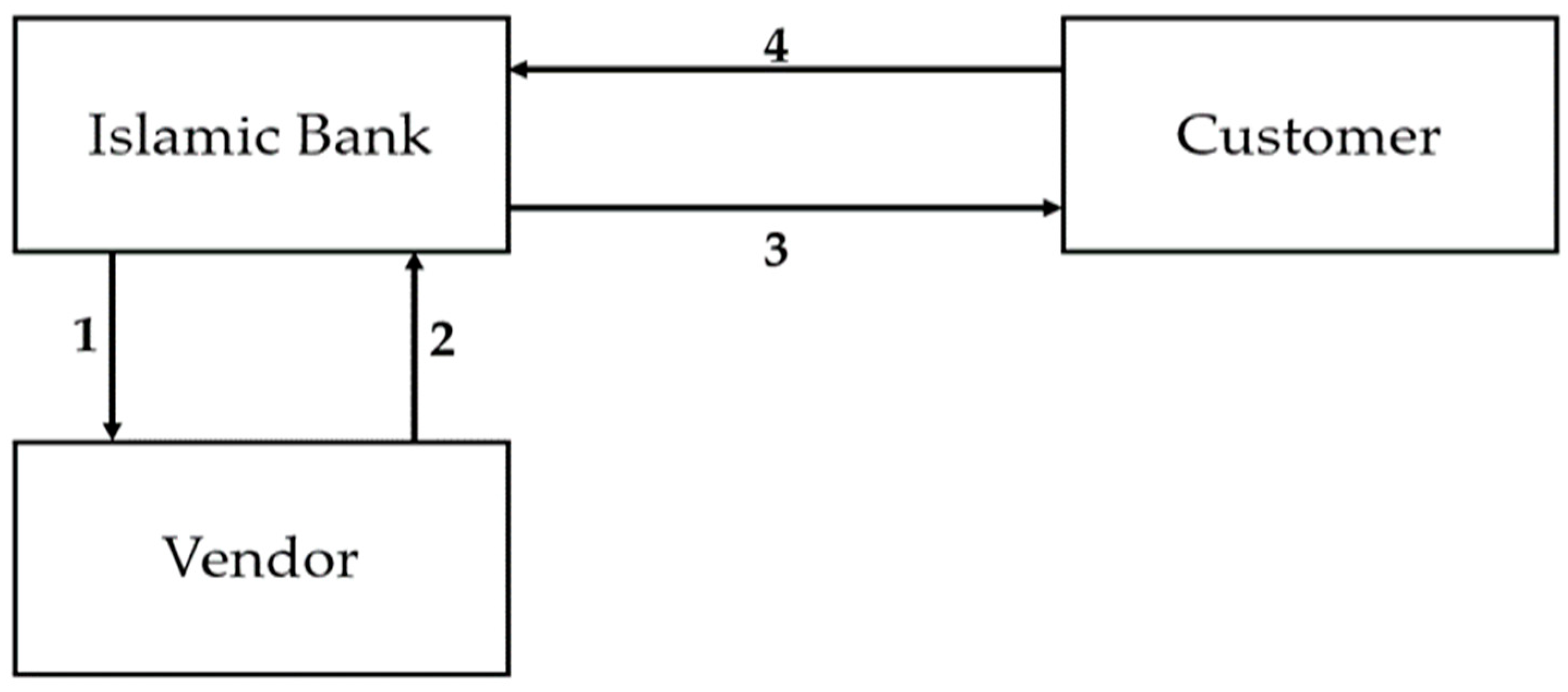

In Islamic law, charging a fixed profit on the sale of goods is permissible as it entails exchanging money for goods (Habib 2018). Consequently, the Islamic bank does not utilize loans when financing customers. Instead, a sales-based transaction such as Murabaha is utilized for this purpose (Habib 2018). In a Murabaha transaction, the Islamic bank agrees with a customer for the purchase of an item to be settled on deferred payment terms, but spot payment is also allowed (Schoon 2016). A vital feature of the Murabaha contract is that the Islamic bank must disclose to the customer the cost and the markup added to the item before the contract is concluded (Zineb and Bellalah 2013). The Islamic bank must, however, effectively enter into two contracts to complete a Murabaha transaction (Visser 2009). The first contract is purchasing the item from a vendor based on the customers’ specifications. In this way, the Islamic bank takes ownership of all related risks of the item, though the Islamic bank will usually secure a promise from the customer to purchase the item, thereby limiting the risk to the Islamic bank (Usmani 2002; Venardos 2006). Thereafter, the second contract is between the Islamic bank and the customer for the actual sale of the item, payable on deferred payment terms. Figure 1 shows the structure of a Murabaha transaction graphically based on the preceding discussion. The item’s selling price must be fixed; thus, the Islamic bank cannot charge amounts more than the fixed selling price as this would be equivalent to charging interest which is not allowed in Islam (Habib 2018; Usmani 2002). The Islamic bank may take some form of security which is permissible, to protect itself against any default of the payment by the customer; however, late payment fees cannot be charged, and if this does happen, the late payment fees must be donated to charity as this amount will be tantamount to interest (Habib 2018). The Islamic bank can provide discounts or allow for early settlement; however, this is at the discretion of the Islamic bank and cannot feature as a condition in the contract with the customer (Usmani 2002).

Figure 1.

Graphical Representation of a Murabaha Contract. Note: (1) Purchase of the item at cost; (2) Delivery of the item to the Islamic bank; (3) Delivery of the item to the customer; (4) Payment by the customer on deferred payment terms.

6. Criticisms of the Murabaha Contract

The Murabaha contract has been heavily criticized in the literature. Some researchers state that this type of contract does not follow Sharia rulings (Aburime and Alio 2009; Khan 2011; Zakariyah 2015). The mark-up arrangement is indistinguishable from interest (Ariff 2014; Pollard and Samers 2007), leading others to assert that this contract facilitates interest through the back door (Aburime and Alio 2009; Bjorvatn 1998). The word ”interest” is replaced with ”profit” to make this contract more appealing to those with religious sensitivities (Khan 2011). The Murabaha contract is a pseudo-Islamic product as it fulfils the form, not the substance of Sharia principles (Asutay 2012; Echchabi and Aziz 2014). This is because Islamic banks compete with conventional banks. This is evident as the Murabaha contract is risk-averse and provides predictable returns on a competitive basis and is thus not different from products offered by conventional banks (Ariff 2014; Roy 1991; Tripp 2006). An advantage to traditional banking is that if the principal amount is paid in full before the contract period concludes, no additional interest charges will be incurred. Still, once a Murabaha transaction is completed, the buyer must pay the profit agreed upon even if the principal amount is paid before the conclusion of the contract period (Khan 2011). Chapra (2008) points out that because of these types of contracts, Islamic banks do not exemplify the altruistic goals expected of them.

7. Accounting for the Murabaha Contract

The Accounting Board at AAOIFI approved Financial Accounting Standard 28 (FAS28): Murabaha and Other Deferred Payment Sales in September 2017. FAS 28 provides the accounting rules for the recognition, measurement, and disclosure of Murabaha contracts carried out by Islamic banks or other Islamic financial institutions (Financial Accounting Standard 28 2017, para. 1). The accounting rules for the initial recognition, subsequent measurement, and derecognition of inventory and Murabaha receivables are provided in Table 3, while the accounting rules for revenue recognition, cost of sales, and deferred profit are provided in Table 4 in line with the accounting standard (Financial Accounting Standard 28 2017, para. 5–28). The discussion of the accounting standard is limited to the accounting rules for the seller (Islamic bank) and does not consider the accounting rules for the purchaser (customer).

Table 3.

Murabaha in the Financial Statements of the Seller (Islamic bank).

Table 4.

Accounting Rules for Revenue, Cost of Sales, and Deferred Profit.

8. Related Studies on Accounting for the Murabaha Contract

A small body of literature is dedicated to the Murabaha contract and its related accounting treatment. The existing studies, however, focus on FAS 2: Murabaha and Murabaha to the Purchase Order which FAS28 has subsequently replaced: Murabaha and Other Deferred Payment Sales. The study by Ahmed et al. (2016), sought to compare the AAOIFI and IFRS accounting standards when accounting for a Murabaha contract. The authors conclude that FAS 2, developed by AAOIFI, considers the Sharia requirements contained within the Murabaha contract and requires profit distribution on a straight-line basis. IFRS accounting standards focus more on the economic consequences of the transaction without considering the need for Sharia compliance. In addition, IFRS allocates profit using the effective interest rate method based on the time value of money principles. Other studies have considered the extent of compliance with AAOIFI standards and concluded that compliance is high when reporting on Murabaha compared to other Sharia-approved contracts (Al-Sulaiti et al. 2018; Vinnicombe 2012). Due to the release of FAS 28, El-Halaby et al. (2021), calls for research to focus on this new accounting standard, which is noted and responded to in this study.

9. The Simulation of a Murabaha Contract

A customer approaches an Islamic bank for financing concerning the purchase of a motor vehicle using a Murabaha contract. The customer has informed the Islamic bank of the motor vehicle specifications and has signed a promise to buy the vehicle from the Islamic bank. The Islamic bank concludes the purchase of the motor vehicle at a cost of $25,000. The Islamic bank immediately enters a Murabaha sales contract with the customer and sells the motor vehicle at $30,000. The vehicle’s cost price and markup of $5000 are disclosed to the customer. The terms of the contract state that annual payments of $6000 will be made over the next five years at an effective profit rate of 6.4 percent.

The amortization schedule is provided in Table 5, which considers the terms and conditions of the Murabaha agreement, and which will be used to account for the transaction throughout the contract.

Table 5.

Amortization Schedule.

The journal entries for the initial recognition of the motor vehicle purchased by the Islamic bank on behalf of the customer are shown in Table 6. The Islamic bank will record Murabaha inventory at a cost price of $25,000.

Table 6.

Purchase of Vehicle from Vendor.

The journal entries to record the Murabaha sale transaction between the Islamic bank and the customer is shown in Table 7. Revenue and a Murabaha receivable are recognized at the selling price of $30,000. The cost of sales is recognized at $25,000, and the Murabaha inventory of $25,000 is derecognized. A deferred profit of $5000 is recognized in the Statement of Financial Position, which will be amortized on a time proportionate basis to the Statement of Income and Expenses.

Table 7.

Sale of Vehicle to Customer.

In Table 8, the journal entries are shown, which consider the annual payments made by the customer and the resulting decrease of the Murabaha receivable balance as well as the deferred profit recognized in the Statement of Income and Expenses over the contractual period.

Table 8.

Accounting for Annual Payments by Customer.

The resulting inflows and outflows from the Murabaha contract are depicted in Table 9 as they appear in the Statement of Income and Expenses. The profit recognized is at its highest in year 1, and after that, lower yields are recognized in subsequent years because of the effective profit rate method.

Table 9.

Statement of Income and Expenses.

Table 10 shows the outstanding balance of the Murabaha receivable and deferred profit account balance as it would appear in the Statement of Financial Position over the Murabaha contractual period.

Table 10.

Statement of Financial Position.

10. Discussion

From the previous analysis, the following can be deduced leading up to the development of modern accounting standards for Islamic banks. The need for accounting systems originated in the Islamic State to record the income and disbursement of zakah, a mandatory tax system within Islam. As the Islamic State grew in sophistication, so did the accounting practice. In the period of the Abbasids, accounting books were classified according to the type of activity performed, for example, the stable journal was used to record livestock within different geographical areas under Muslim control. Transactions recorded had to capture several details to keep complete and accurate records. Furthermore, those appointed for record-keeping had to display qualities such as being technically competent and trustworthy. Due to the advanced accounting system employed during this period, some scholars (see Solas and Otar 1994; Zaid 2000) opine that modern accounting has its roots in ancient Arabia rather than Italy as is widely believed.

In the modern era, Muslims desired to establish Islamic practice in all areas of life. This led to the conception of Islamic banking to cater to the needs of Muslims for Sharia-compliant banking. Consequently, accounting standards were required to report on the unique contracts used by Islamic banks. The AAOIFI was established for this purpose and has developed several standards that cater specifically to the contracts used by Islamic banks. FAS 28 is the latest iteration by AAOIFI for the accounting treatment of the Murabaha contract. The Murabaha contract is a sales contract in which the Islamic bank provides financing to a customer by providing an asset in exchange for money. The Murabaha contract requires that the Islamic bank disclose the cost and markup to the customer before the contract is concluded.

From the simulation of the Murabaha contract, the following observations are offered. Deferred profit is recognized using the effective profit rate method on a time-proportionate basis. This is, in essence, the “interest” rate method from conventional financing; however, scholars such as Muhamat et al. (2011) convey that Islamic banks use terminology that appeals to customers to gain a competitive advantage. Using the effective profit rate method is a departure from the previous accounting standard for Murabaha, which required profit to be allocated on a straight-line basis (Ahmed et al. 2016). This means that both AAOIFI and IFRS use the amortized cost method to account for the Murabaha contract, resulting in higher cashflows at the beginning of the contract, which subsequently reduces over the period of the contract.

The conventional methods of accounting and Islamic accounting are similar as both apply double-entry book-keeping. What differs is that Islamic accounting standards cater specifically to contracts used by Islamic banks and other Islamic financial institutions. Ahmed et al. (2016) have also drawn these conclusions as they state that AAOIFI standards consider Sharia requirements, while other accounting reporting frameworks, for example, IFRS, focus more on the economic consequences of transactions. However, Nethercott and Eisenberg (2012) point out that contracts such as Murabaha can be accounted for using IFRS; the only difference is that a few accounting standards, for instance, IAS 2: Inventories, IFRS: 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers and IFRS 9: Financial Instruments, would need to be used, as opposed to having just one standard as is the case for AAOIFI. Further to this, Velayutham (2014) points out that another significant difference is that AAOIFI standards require the disclosure of information that aligns with the investment criteria of Muslims.

The previous discussion has highlighted that AAOIFI standards are more efficient in capturing the essence of contracts and require additional levels of disclosures deemed important for investors concerned with Sharia-compliance by Islamic banks. The AAOIFI standards also capture the religious norms of Muslims, which may be legitimized and more easily acceptable by the “group” as these standards encompass the worldview being Sharia compliance that underpins Islamic banking. However, it must be pointed out that IFRS could be and may be required in some jurisdictions due to legal requirements to account for and report on contracts used by the Islamic bank; however, using IFRS standards would require the assistance of multiple standards in addition to the possibility of providing disclosures that do not consider Sharia requirements. A final observation arising from the study is that accounting standards produced by AAOIFI follow the normal accounting conventions. What makes AAOIFI standards different from conventional accounting standards is the fact that AAOIFI standards are designed to capture and report Sharia-approved contracts. Thus, the expression ”Sharia contract accounting” may be more fitting than the expression ”Islamic accounting”.

11. Conclusions

The study considered the events leading to the development of modern accounting standards for Islamic banks and, thereafter, the accounting process and related impact on the financial statements for the Murabaha contract. The tax system used in the early Islamic state created a need for accounting systems and processes. As the Islamic state grew, there were improvements in the sophistication of the accounting systems used, such as the use of specific journals and the need for detailed and accurate records. In the modern era, the advent of the Islamic banking industry created a need to develop specific accounting standards, resulting in the formation of AAOIFI. The AAOIFI developed FAS 28: Murabaha and Other Deferred Payment Sales, which requires the use of the effective profit rate method on a time proportionate basis when accounting for a Murabaha contract; however, some authors argue that conventional accounting standards are also suitable for reporting on the Murabaha contract.

In the future, studies should take this debate further by analyzing, using case studies, the differences and similarities shared between AAOIFI and IFRS accounting standards and in practice, if there are differences in the levels of disclosure provided. Studies can also consider the applicability of using conventional accounting standards for accounting for contracts used in Islamic banking and provide recommendations on how these traditional accounting standards can be improved to accurately reflect the economic and Sharia consequences of Sharia-approved contracts. Studies can also consider how a parent company that uses AAOIFI accounting standards reconciles the group consolidated financial statements particularly where subsidiary companies comply with conventional reporting frameworks. Studies can also consider the compliance of Islamic banks with FAS 28. Finally, studies can also consider the need for a dedicated auditing standard for Murabaha contracts to alleviate challenges and create harmony when auditing such transactions across jurisdictions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- AAOIFI. 2023. Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions. Available online: https://aaoifi.com/?lang=en (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Abdel Karim, Rifaat A. 1995. The nature and rationale of a conceptual framework for financial reporting by Islamic banks. Accounting and Business Research 25: 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Karim, Rifaat A. 2001. International accounting harmonization, banking regulation, and Islamic banks. The International Journal of Accounting 36: 169–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Magid, Mostafa F. 1981. The theory of Islamic banking: Accounting implications. International Journal of Accounting 17: 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Aburime, Toni, and Felix Alio. 2009. Islamic banking: Theories, practices and insight for Nigeria. International Review of Business Research Papers 5: 321–39. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1262291 (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Ahmed, Mezbah U., Ruslan Sabirzyanov, and Romzie Rosman. 2016. A critique on accounting for Murabaha contract: A comparative analysis of IFRS and AAOIFI accounting standards. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 7: 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akacem, Mohammed, and Lynde Gilliam. 2002. Principles of Islamic banking: Debt versus equity finance. Middle East Policy IX: 124–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Nafis, Lokesh Gupta, and Bala Shanmugam. 2017. Islamic Finance: A Practical Perspective. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Aldohni, Abdul Karim. 2015. The quest for a better legal and regulatory framework for Islamic banking. Ecclesiastical Law Society 17: 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sulaiti, Jabir, Abulrahman Anam Ousama, and Helmi Hamammi. 2018. The compliance of disclosure with AAOIFI financial accounting standards: A comparison between Bahrain and Qatar Islamic banks. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 9: 549–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambashe, Mohamud, and Hikmat A. Alrawi. 2013. The development of accounting through the history. International Journal of Advances in Management and Economics 2: 95–100. Available online: https://www.managementjournal.info/index.php/IJAME/article/view/261 (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Ariff, Mohamed. 1988. Islamic banking. Asian-Pacific Economic Literature 2: 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariff, Mohamed. 2014. Whiter Islamic banking. The World Economy 37: 733–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan-Ayaydin, Ozgur, Kris Boudt, and Muhammad Wajid Raza. 2018. Avoiding interest-based revenues while constructing Shariah-compliant portfolios: False negatives and false positives. The Journal of Portfolio Management 44: 136–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, Hossein, Zamir Iqbal, and Abbas Mirakhor. 2009. New Issues in Islamic Finance & Economics: Progress & Challenges. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Askary, Saeed, and Frank L. Clarke. 1997. Accounting in the Koranic verses. In Islamic Accounting. Edited by Christopher Napier and Roszaini Haniffa. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 144–58. [Google Scholar]

- Asutay, Mehmet. 2007. A political economy approach to Islamic economics: Systemic understanding for an alternative economic system. Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Studies 1: 1–15. Available online: https://dro.dur.ac.uk/4530/1/4530.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Asutay, Mehmet. 2008. Islamic banking and finance: Social failure. New Horizon—Global Perspectives on Islamic Banking and Insurance 169: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asutay, Mehmet. 2012. Conceptualising and locating the social failure of Islamic finance: Aspirations of Islamic moral economy vs. the realities of Islamic finance. Asian and African Area Studies 11: 93–113. Available online: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/asafas/11/2/11_93/_pdf (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Benamraoui, Abdelhafid. 2008. Islamic banking: The case of Algeria. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 1: 113–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billah, Mohd Ma’sum. 2007. Islamic banking and the growth of takaful. In Handbook of Islamic Banking. Edited by Mohammad K. Hassan and Mervin K. Lewis. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 401–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorvatn, Kjetil. 1998. Islamic Economics and Economic Development. Forum for Development Studies 2: 229–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutayeba, Faical, Mohammed Benhamida, and Souad Guesmi. 2014. Ethics in Islamic economics. Annales. Ethics in Economic Life 17: 111–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebeci, Ismail. 2012. Integrating the social maslaha into Islamic finance. Accounting Research Journal 25: 166–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapra, Muhamed Umer. 2008. The Global Financial Crisis: Can Islamic Finance Help Minimize the Severity and Frequency of Such a Crisis in the Future. A paper presentation at the forum on the Global Financial Crisis. Jeddah: Islamic Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, Saida, and Mohamed Frikha. 2016. Islamic finance: Basic principles and contributions in financing economic. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 7: 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, Humayon A. 2007. Incentive compatibility of Islamic financing. In Handbook of Islamic Banking. Edited by Mohammad K. Hassan and Mervin K. Lewis. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, Graeme, and Frank Clarke. 2003. An Evolving conceptual framework. Abacus 39: 279–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusuki, Asyraf Wajdi, and Abdulazeem Abozaid. 2007. A critical appraisal on the challenges of realising maqasid al-Shariah in Islamic banking and finance. Journal of Economics and Management 15: 143–65. Available online: https://journals.iium.edu.my/enmjournal/index.php/enmj/article/view/133 (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Echchabi, Abdelghani, and Hassanuddeen Abd Aziz. 2014. Shari’ah issues in Islamic banking: A qualitative survey in Malaysia. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets 6: 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfakhani, Said M., Imad J. Zbib, and Zafar U. Ahmed. 2007. Marketing of Islamic financial products. In Handbook of Islamic Banking. Edited by Mohammad K. Hassan and Mervin K. Lewis. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 116–27. [Google Scholar]

- El-Gamal, Mahmoud A. 2006. Islamic Finance: Law, Economics, and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- El-Halaby, Sherif, Sameh Aboul-Dahab, and Nuha Bin Qoud. 2021. A systematic literature review on AAOIFI standards. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 19: 133–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Accounting Standard 28. 2017. Murabaha and Other Deferred Payment Sales. Available online: https://aaoifi.com/e-standards/?lang=en (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Gattoo, Mujeeb Hussain, and Muneeb Hussain Gattoo. 2017. Modern economics and the Islamic alternative: Disciplinary evolution and current crisis. International Journal of Economics, Management and Accounting 25: 173–203. Available online: https://journals.iium.edu.my/enmjournal/index.php/enmj/article/view/494 (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Ghauri, Shahid Muhammad Khan, and Amal Sabah Obaid Qambar. 2012. Rewards in faith-based vs conventional banking. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets 4: 176–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginena, Karim. 2013. Shari’ah risk and corporate governance of Islamic banks. Corporate Governance 14: 86–103. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2355872 (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Gray, Sidney. 1988. Towards a theory of cultural influence on the development of accounting systems internationally. Abacus 24: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, Syeda Fahmida. 2018. Fundamentals of Islamic Finance and Banking. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, Shaari, Russell Craig, and Frank Clarke. 1995. Bookkeeping and accounting control systems in a tenth-century Muslim administrative office. Accounting, Business and Financial History 5: 321–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, Muhammad. 2011. Differences and similarities in Islamic and conventional banking. International Journal of Business and Social Science 2: 166–75. Available online: http://www.ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol._2_No._2%3B_February_2011/20.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Haniffa, Roszaini, and Mohammad Hudaib. 2002. A theoretical framework for the development of the Islamic perspective of accounting. Accounting, Commerce and Finance: The Islamic Perspective Journal 6: 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Haniffa, Roszaini, and Mohammad Hudaib. 2007. Exploring the ethical identity of Islamic banks via communication in annual reports. Journal of Business Ethics 76: 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, Roszaini, Mohammad Hudaib, and Abul Malik Mirza. 2002. Accounting Policy Choice within the Shari’ah Islami’iah Framework. Discussion Papers in Accountancy and Finance, Working Paper 02/04. Exeter: School of Business and Economics, University of Exeter, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Heidhues, Eva, and Chris Patel. 2011. A critique of Gray’s framework on accounting values using Germany as a case study. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 22: 273–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, Geert. 1984. Cultural dimensions in management and planning. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 1: 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Abdul Ghafar B., and Achmad Tohirin. 2010. Islamic law and finance. Humanomics 26: 178–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaldeen, Faleel. 2012. Islamic Finance for Dummies. Hoboken: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Jawadi, Fredj, Abdoulkarim Idi Cheffou, and Nabila Jawadi. 2016. Do Islamic and conventional banks really differ? A panel data statistical analysis. Open Economies Review 27: 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, Yusuf. 2013. Examining the meta-principles of modern economics and the implications for Islamic banking and finance. Islamic Sciences 11: 169–84. Available online: https://cis-ca.org/_media/pdf/2013/2/TEM_temetmomeatifibaf.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Kahf, Monzer. 1999. Islamic banks at the threshold of the third millennium. Thunderbird International Business Review 41: 445–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahf, Monzer. 2007. Islamic banks and economic development. In Handbook of Islamic Banking. Edited by Mohammad K. Hassan and Mervin K. Lewis. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 277–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kazi, Ashraf U., and Abdel K. Halabi. 2006. The influence of Quran and Islamic financial transactions and banking. Arab Law Quarterly 20: 321–31. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27650555 (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Kettell, Brian. 2010. Frequently Asked Questions in Islamic Finance. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Kettell, Brian. 2011. Introduction to Islamic Banking and Finance. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Madiha. 2011. Islamic banking practices: Islamic law and prohibition of riba. Islamic Studies 50: 413–22. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41932604 (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Khan, Mansoor M., and Ishaq M. Bhatti. 2008. Islamic banking and finance: On its way to globalization. Managerial Finance 34: 708–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Muhammad Akram. 2013. What Is Wrong with Islamic Economics? Analysing the Present State and Future Agenda. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kholvadia, Faatima. 2017. Islamic banking in South Africa—Form over substance. Meditari Accountancy Research 25: 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuran, Timur. 1995. Islamic economics and the Islamic subeconomy. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 9: 155–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahsasna, Ahcene. 2014. Sharia Non-Compliance Risk Management and Legal Documentation in Islamic Finance. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Mervin K. 2001. Islam and accounting. Accounting Forum 25: 103–27. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1467-6303.00058?journalCode=racc20 (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Lica, Madalina. 2015. The origins and development of Islamic economics. Cogito VII: 80–91. Available online: https://cogito.ucdc.ro/cogito7.nr2.june.pdf#page=80 (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Mansour, Walid, Khoutem Ben Jedidia, and Jihed Majdoub. 2015. How ethical is Islamic banking in the light of the objectives of Islamic law. Journal of Religious Ethics 43: 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirakhor, Abbas, and Iqbal Zaidi. 2007. Profit-and-loss sharing contracts in Islamic finance. In Handbook of Islamic Banking. Edited by Mohammad K. Hassan and Mervin K. Lewis. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, Nor Farizal, Fadzlina Mohd Fahmi, and Asyaari Elmiza Ahmad. 2015. The influence of AAOIFI accounting standards in reporting Islamic financial institutions in Malaysia. Procedia Economics and Finance 31: 418–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosa, Riyad. 2022. The role of customer selection criteria, banking objective, CSR, and service quality in enhancing positive customer perception: An Islamic banking perspective. International Journal of Economics and Finance Studies 14: 388–408. [Google Scholar]

- Moosa, Riyad, and Smita Kashiramka. 2022. Objectives of Islamic banking, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty: Empirical evidence from South Africa. Journal of Islamic Marketing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamat, Amirul Afif, Mohamad Nizam Jaafar, and Norfaridah Binti Ali Azizan. 2011. An empirical study on banks’ clients’ sensitivity towards the adoption of Arabic terminology among Islamic banks. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 4: 343–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtuza, Athar. 2002. Islamic antecedents for financial accountability. In Islamic Accounting. Edited by Christopher Napier and Roszaini Haniffa. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 203–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan, Samy, and Chris Pierce. 2009. CSR in Islamic financial institutions in the Middle East. In Corporate Social Responsibility: A Case Study Approach. Edited by Christine A. Mallin. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 258–73. [Google Scholar]

- Nethercott, Craig R., and David M. Eisenberg. 2012. Islamic Finance Law and Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nouman, Muhammad, Karim Ullah, and Saleem Gul. 2018. Why Islamic banks tend to avoid participatory financing? A demand, regulation, and uncertainty framework. Business & Economic Review 10: 1–32. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3214064 (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Oshodi, Basheer A. 2014. An Integral Approach to Development Economics: Islamic Finance in an African Context. Aldershot: Gower. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, Jane, and Michael Samers. 2007. Islamic banking and finance: Postcolonial political economy and the decentring of economic geography. Royal Geographical Society 32: 313–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramabulana, Khuthadzo, and Riyad Moosa. 2022. Disclosure of Risks and Opportunities in the Integrated Reports of South African Banks. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, Delwin A. 1991. Islamic banking. Middle Eastern Studies 27: 427–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidani, Raoudha, Neila Boulila Taktak, and Khaled Hussainey. 2021. The determinants of investment account holders’ disclosure in Islamic banks: International Evidence. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sairally, Salma. 2007. Community development financial institutions: Lessons in social banking for the Islamic financial industry. Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Study 1: 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, Kautsar Riza. 2022. Exploring the history of Islamic accounting and the concept of accountability in an Islamic perspective. Journal of Islamic Economic and Business Research 2: 114–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, Natalie. 2016. Modern Islamic Banking: Products and Processes in Practice. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Sharair, Mohammad, Jesmin Islam, and Harun Harun. 2013. A history of the development of Islamic accounting standards: An investigation of the influence of key players. Conference presentation. Paper presented at 9th Asian Business Research Conference, BIAM Foundation, Dhaka, Bangladesh, December 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Shaukat, Mughees, Mohammad Saeed Rahman, and Saji Luka. 2017. The nexus between business ethics and economics justice: An Islamic framework. Journal of Economic Development, Management, IT, Finance and Marketing 9: 1–11. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1861052108 (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Solas, Cigdem, and Ismail Otar. 1994. The accounting system practiced in the Near East during the period 1220–350 based on the book Risale-I Felekiyye. Accounting Historians Journal 21: 117–35. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40698133 (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Sulaiman, Maliah, and Roger Willett. 2001. Islam, Economic rationalism and accounting. American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences 18: 61–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlemsani, Issam. 2010. Co-evolution and reconcilability of Islam and the west: The context of global banking. Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues 3: 262–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripp, Charles. 2006. Islam and the Moral Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trokic, Amela. 2015. Islamic accounting; history, development and prospects. European Journal of Islamic Finance 3: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, Muhammad Taqi. 2002. An Introduction to Islamic Finance. Alphen aan den Rijn: Kluwer Law International. [Google Scholar]

- Velayutham, Sivakumar. 2014. Conventional accounting vs Islamic accounting: The debate revisited. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 5: 126–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venardos, Angelo M. 2006. Islamic Banking & Finance in South-East Asia: Its Development & Future. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Vinnicombe, Thea. 2012. A study of compliance with AAOIFI accounting standards by Islamic banks in Bahrain. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 3: 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, Hans. 2009. Islamic Finance Principles and Practice. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wahyudi, Muhammad, Sri Herianingrum, and Ririn Ratnasari. 2022. Examining the trend, themes, and social structure of the Islamic Accounting using a bibliometric approach. Jurnal Ekonomi dan Bisnis Islam 8: 153–78. Available online: https://e-journal.unair.ac.id/JEBIS/article/view/34073/23286 (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Warde, Ibrahim. 2012. Status of the Global Islamic Finance Industry. In Islamic Finance: Law and Practice. Edited by Craig R. Nethercott and David M. Eisenberg. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yanikkaya, Halit, and Yasar Ugur Pabuccu. 2017. Causes and solutions for the stagnation of Islamic banking in Turkey. ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance 9: 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, Omar Abdullah. 2000. Were Islamic records precursors to accounting books based on the Italian method. Accounting Historians Journal 27: 73–90. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/288025182.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Zakariyah, Luqman. 2015. Harmonising legality with morality in Islamic banking and finance: A quest for Maqasid al-shari’ah paradigm. Intellectual Discourse 23: 355–76. Available online: https://journals.iium.edu.my/intdiscourse/index.php/id/article/view/700 (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Zia, Mehwish Darakhshan, and Nida Nasir-Ud-Din. 2016. Islamic economic rationalism and distribution of wealth: A comparative view. Journal of Business and Management 18: 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zineb, Shayeh, and Mondher Bellalah. 2013. Introduction to Islamic finance and Islamic banking: From theory to innovations. In Islamic Banking and Finance. Edited by Mondher Bellalah and Omar Masood. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).