Factors Influencing Key Audit Matter Reporting in the Stock Exchange of Thailand: Empirical Evidence from 2016–2020 Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

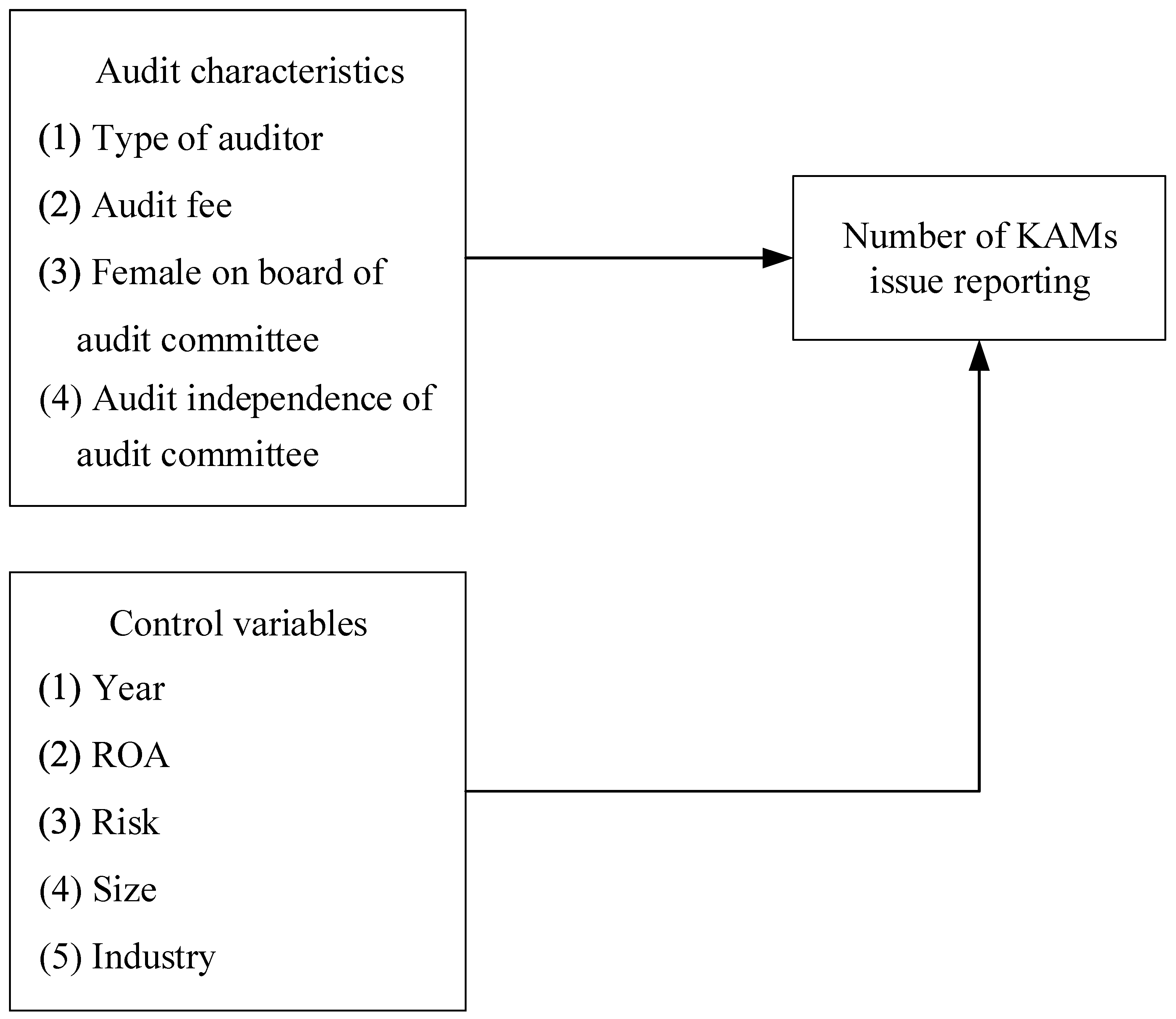

- To explore the number of KAM issues in the Thai audit report.

- To understand the related variables with the KAM issues pertaining to the existing literature.

- To analyze the impact of the selected variables under the second objective on the Thai audit report.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdullatif, Modar. 2016. Auditing fair value estimates in developing countries: The case of Jordan. Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 9: 101–40. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullatif, Modar, Rami Alzebdieh, and Saeed Ballour. 2023. The effect of key audit matters on the audit report lag: Evidence from Jordan. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-effect-of-key-audit-matters-on-the-audit-report-Abdullatif-Alzebdieh/48346840d582946b0910ff622606515d91f760f3 (accessed on 7 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Abu, Nor’asyiqin, and Romlah Jaffar. 2020. Audit Committee Effectiveness and Key Audit Matters. Asian Journal of Accounting & Governance 14: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Al-mulla, Mazen, and Michael E. Bradbury. 2022. Auditor, client and investor consequences of the enhanced auditor’s report. International Journal of Auditing 26: 134–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorelli, María-Florencia, and Isabel-María García-Sánchez. 2021. Trends in the dynamic evolution of board gender diversity and corporate social responsibility. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 28: 537–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, Nasrin, and E-Vahdati Sahar. 2022. Reliable Financial Statements: External Auditing System or Financial Statement Insurance? Asian Journal of Accounting Perspectives 15: 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Baatwah, Saeed Rabea, Ehsan Saleh Almoataz, Waddah Kamal Omer, and Khaled Salmen Aljaaidi. 2022. Does KAM disclosure make a difference in emerging markets? An investigation into audit fees and report lag. International Journal of Emerging Markets 3: 798–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bédard, Jean, Nathalie Gonthier-Besacier, and Alain Schatt. 2019. Consequences of expanded audit reports: Evidence from the justifications of assessments in France. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 38: 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bepari, Md Khokan. 2023. Audit committee characteristics and Key Audit Matters (KAMs) disclosures. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance 34: 152–72. [Google Scholar]

- Boonlert-U-Thai, Kriengkrai, and Muttanachai Suttipun. 2023. Influence of external and internal auditors on key audit matters (KAMs) reporting in Thailand. Cogent Business & Management 10: 2256084. [Google Scholar]

- Boonlert-U-Thai, Kriengkrai, Sillapaporn Srijunpetch, and Anuwat Phakdee. 2019. Key audit matters: What they tell. Journal of Accounting Profession 15: 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Boonyanet, Wachira, and Waewdao Promsen. 2018. Key audit matters: Just little informative value to investors in emerging markets? Chulalongkorn Business Review 41: 153–83. [Google Scholar]

- Chinpuvadol, Patsuntorn, and Wachira Boonyanet. 2020. The Audit Expectation GAP Between Auditors and Financial Statements’ Users. Journal of Federation of Accounting Professions 5: 4–33. [Google Scholar]

- Doxey, Marcus. 2014. The Effects of Auditor Disclosures Regarding Management Estimates on Financial Statement Users’ Perceptions and Investments. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2181624 (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- IAASB. 2013. Reporting on Audited Financial Statements: Proposed New and Revised International Standards on Auditing (ISAs). Available online: https://www.iaasb.org/publications/reporting-audited-financial-statements-proposed-new-and-revised-international-standards-auditing (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Elmarzouky, Mahmoud, Khaled Hussainey, and Tarek Abdelfattah. 2022. The key audit matters and the audit cost: Does governance matter? International Journal of Accounting & Information Management 31: 195–217. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Rob, Reza Kouhy, and Simon Lavers. 1995. Corporate social and environmental reporting: A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 8: 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosu, Maria, Ioan-Bogdan Robu, and Costel Istrate. 2020. The Quality of Financial Audit Missions by Reporting the Key Audit Matters. Audit Financiar 18: 182–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, Elizabeth, Miguel Minutti-Meza, Kay W. Tatum, and Maria Vulcheva. 2018. Consequences of adopting an expanded auditor’s report in the United Kingdom. Review of Accounting Studies 23: 1543–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, Ahsan, Mabel D. Costa, Hedy Jiaying Huang, Md Borhan Uddin Bhuiyan, and Li Sun. 2020. Determinants and consequences of financial distress: Review of the empirical literature. Accounting & Finance 60: 1023–75. [Google Scholar]

- Huse, Morten, and Anne Grethe Solberg. 2006. Gender-related boardroom dynamics: How Scandinavian women make and can make contributions on corporate boards. Women in Management Review 21: 113–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, Norazian, Mohd Fairuz Md Salleh, Azlina Ahmad, and Mohd Mohid Rahmat. 2023. The association between audit firm attributes and key audit matters readability. Asian Journal of Accounting Research 8: 322–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAASB. 2020. Handbook of International Quality Control, Auditing, Review, Other Assurance, and Related Services Pronouncements. Available online: https://www.iaasb.org/publications/2020-handbook-international-quality-control-auditing-review-other-assurance-and-related-services (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Intagool, Wanitcha, Jomjai Sampet, and Wanisara Suwanmongkol. 2020. Communication Value of Key Audit Matters in Auditor’s Report of Companies in Services Industry Listed on The Stock Exchange of Thailand. Business Review Journal 12: 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- International Standard on Auditing 701: Communicating Key Audit Matters in the Independent Auditor’s Report. 2016. Available online: https://www.iaasb.org/publications/international-standard-auditing-isa-701-new-communicating-key-audit-matters-independent-auditor-s-3 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. 2019. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. In Corporate Governance. Edited by R. I. Tricker. London: Taylor & Francis, pp. 77–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal Metawee, Ahmed, Eman Magdi Fawzi Mohammed Ali, and Mostafa Ibrahim EL-Feky. 2024. The Impact of Key Audit Matters Disclosure on Debt Cost: An Applied Study. The Egyptian Journal of business Studies 48: 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamwass, Supunnee, Pattanant Petchchedchoo, and Siridech Kumsuprom. 2020. Key audit matters disclosure and market value of thai listed companies. Suthiparithat Journal 34: 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kanno, Patcharaphun, and Prawase Penwuttikul. 2018a. Factors affecting disclosure quality on key audit matters in auditor’s report in thailand. Journal of MCU Nakhondhat 5: 926–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kanno, Patcharaphun, and Prawase Penwuttikul. 2018b. KAM and Alteration of Auditor’s Report that Challenge Certified Public Accountant (CPA). Paper presented at the UTCC Academic Day, Bangkok, Thailand, June 8. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Arifur, Mohammad Badrul Muttakin, and Javed Siddiqui. 2013. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosures: Evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of Business Ethics 14: 207–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitiwong, Weerapong, and Naruanard Sarapaivanich. 2020. Consequences of the implementation of expanded audit reports with key audit matters (KAMs) on audit quality. Managerial Auditing Journal 35: 1095–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitiwong, Weerapong, and Sillapaporn Srijunpetch. 2019. Cultural influences on the disclosures of key audit matters. Journal of Accounting Profession 15: 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Knechel, W. Robert, and Marleen Willekens. 2006. The role of risk management and governance in determining audit demand. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 33: 1344–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Karen M. Y., Bin Srinidhi, Ferdinand A. Gul, and Judy S. L. Tsui. 2017. Board Gender Diversity, Auditor Fees and Auditor Choice. Contemporary Accounting Research 34: 1681–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuz, Christian, and Peter D. Wysocki. 2016. The economics of disclosure and financial reporting regulation: Evidence and suggestions for future research. Journal of Accounting Research 54: 525–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Wenhao, Hua Gong, Huitong Zhou, Jiqing Wang, Shaobin Li, Xiu Liu, Yuzhu Luo, and Jon G. H. Hickford. 2019. Variation in KRTAP6-1 affects wool fibre diameter in New Zealand Romney ewes. Archives Animal Breeding 62: 509–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Hsiao-Lun, and Ai-Ru Yen. 2022. Auditor rotation, key audit matter disclosures, and financial reporting quality. Advances in Accounting 57: 100594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litjens, Robin, Joost van Buuren, and Ruud Vergoossen. 2015. Addressing Information Needs to Reduce the Audit Expectation Gap: Evidence from Dutch Bankers, Audited Companies and Auditors. International Journal of Auditing 19: 267–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheesuwapab, Sajeerat. 2018. The nature in reporting of the key Audit Matters (KAM): The judgment in writing key audit matter of certified public accountant from big four accounting firms. Suthiparithat Journal 32: 210–22. [Google Scholar]

- McGeachy, Dawn, and Christopher Arnold. 2017. Auditor Reporting Standards Implementation: Key Audit Matters. Available online: https://www.ifac.org/knowledge-gateway/discussion/auditor-reporting-standards-implementation-key-audit-matters (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- McKee, Dale. 2015. New external audit report standards are game changing. Governance Directions 67: 222–25. [Google Scholar]

- Meckling, William H., and Michael C. Jensen. 1976. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar]

- Meechumnan, Pannipa, Naruanard Sarapaivanich, Tulaya Tulardilok, and Maleemas Sittisombut. 2019. Communication Value of Key Audit Matters of Companies in Property and Construction Industry Group Listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand. WMS Journal of Management 8: 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Moroney, Robyn, Soon-Yeow Phang, and Xinning Xiao. 2021. When do investors value key audit matters? European Accounting Review 30: 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, C. Stewart, and Nicholas S. Majluf. 1984. Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics 13: 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neerapattanakun, Duangkamon. 2023. How does the Implementation of TFRS 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers affect the change from the Application? Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Nakhon Phanom University 13: 96–113. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Lan Anh, and Michael Kend. 2021. The perceived impact of the KAM reforms on audit reports, audit quality and auditor work practices: Stakeholders’ perspectives. Managerial Auditing Journal 36: 437–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuntathanakan, Kajohn, Naruanard Sarapaivanich, Amonlaya Kosaiyakanont, and Wanitsara Suwanmongkol. 2020. Communication Value of Key Audit Matters of Companies in Financials Group Listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand. Journal of Management Sciences 37: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- OECD Corporate Governance Factbook 2021. 2021. Paris: OECD.

- Parte, Laura, María-Del-Mar Camacho-Miñano, María-Jesús Segovia-Vargas, and Yolanda Pérez-Pérez. 2022. How difficult is to understand the extended audit report? Cogent Business & Management 9: 2113494. [Google Scholar]

- Petrick, A. Joseph, and Robert F. Scherer. 2003. The Enron scandal and the neglect of management integrity capacity. American Journal of Business 18: 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, Ines, and Ana Isabel Morais. 2019. What matters in disclosures of key audit matters: Evidence from Europe. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting 30: 145–62. [Google Scholar]

- Porumbăcean, Teodora, and Adriana Tiron-Tudor. 2021. Factors Influencing KAM Reporting: A Structured Literature Review. Audit Financiar 4: 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratoomsuwan, Thanyawee, and Orapan Yolrabil. 2018. The key audit matter (KAM) practices: The review of first year experience in Thailand. NIDA Business Journal 23: 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Pratoomsuwan, Thanyawee, and Orapan Yolrabil. 2020a. Key audit matter and auditor liability: Evidence from auditor evaluators in Thailand. Journal of Applied Accounting Research 21: 741–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratoomsuwan, Thanyawee, and Orapan Yolrabil. 2020b. The The Role of Key Audit Matters in Assessing Auditor Liability: Evidence from Auditor and Non-auditor Evaluators. Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 13: 35–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punyaviwat, Gunyanun, and Wachira Boonyanet. 2020. Key audit matters and their risk responses of possible delisting companies. Journal of Federation of Accounting Professions 5: 54–75. [Google Scholar]

- Rahaman, Md Mustafizur, Md Moazzem Hossain, and Md Borhan Uddin Bhuiyan. 2023. Disclosure of key audit matters (KAMs) in financial reporting: Evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 13: 666–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, Bruce. 2009. The correlation coefficient: Its values range between +1/-1, or do they? Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing 17: 139–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautiainen, Antti, Jani Saastamoinen, and Kati Pajunen. 2021. Do key audit matters (KAMs) matter? Auditors’ perceptions of KAMs and audit quality in Finland. Managerial Auditing Journal 36: 386–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, C. Lauren, Joseph V. Carcello, Chan Li, Terry L. Neal, and Jere R. Francis. 2019. Impact of auditor report changes on financial reporting quality and audit costs: Evidence from the United Kingdom. Contemporary Accounting Research 36: 1501–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samakketkarnpol, Sasiprapa. 2019. Key audit matters, Audit quality and Earnings management of initial public offerings in the stock exchange of Thailand. Suthiparithat Journal 33: 210–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sawangjan, Phattarawade, and Muttanachai Suttipun. 2020. The Relationship Between Key Audit Matters (KAMS) Disclosure and Stock Reaction: Cross-Sectional Study of Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore. Journal of Finance & Banking Review (JFBR) 5: 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Xin. 2020. Research on Disclosure Status and Influencing Factors of Key Audit Matters. Modern Econom 11: 701–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-García, Laura, Nicolás Gambetta, María A. García-Benau, and Manuel Orta-Pérez. 2019. Understanding the determinants of the magnitude of entity-level risk and account-level risk key audit matters: The case of the United Kingdom. British Accounting Review 51: 227–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryanto, Tejo, J. E. Thalassinos, and E. I. Thalassinos. 2017. Board characteristics, audit committee and audit quality: The case of Indonesia. International Journal of Economics and Business Administration 5: 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šušak, Toni. 2020. The Impact of Key Audit Matters on Cost of Debt. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375671821_The_Impact_of_Key_Audit_Matters_on_Cost_of_Debt (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Suttipun, Muttanachai. 2022. External auditor and KAMs reporting in alternative capital market of Thailand. Meditari Accountancy Research 30: 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanstraelen, Ann, Caren Schelleman, Roger Meuwissen, and Isabell Hofmann. 2012. The Audit Reporting Debate: Seemingly Intractable Problems and Feasible Solutions. European Accounting Review 21: 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, Patrick. 2018. Does gender diversity in the audit committee influence key audit matters’ readability in the audit report? UK evidence. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 25: 748–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, Patrick. 2020. Associations between the financial and industry expertise of audit committee members and key audit matters within related audit reports. Journal of Applied Accounting Research 21: 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, Patrick, and Jakob Issa. 2019. The impact of key audit matter (KAM) disclosure in audit reports on stakeholders’ reactions: A literature review. Problems and Perspectives in Management 17: 323–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, L. Ross, and Jerold L. Zimmerman. 1979. The demand of and supply for accounting theories. The Accounting Review 54: 273–305. [Google Scholar]

- Wuttichindanon, Suneerat, and Panya Issarawornrawanich. 2020. Determining factors of key audit matter disclosure in Thailand. Pacific Accounting Review 32: 563–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Xin, Fengying Ye, and Yasheng Chen. 2023. The joint effect of investors’ trait scepticism and the familiarity and readability of key audit matters on the communicative value of audit reports. China Journal of Accounting Studies 11: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarana, Chanida, Suntaree Tungsriwong, Pattaraporn Pongsaporamat, and Sirat Sonchai. 2018. Communicating key audit matters of listed firms in Stock Exchange of Thailand. International Journal of Applied Computer Technology and Information Systems 8: 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Minghe. 2019. The Effect of Key Audit Matters on Firms’ Capital Cost: Evidence from Chinese Market. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336825954_The_Effect_of_Key_Audit_Matters_on_Firms%27_Capital_Cost_Evidence_from_Chinese_Market (accessed on 7 October 2024).

| Author(s) | Objectives | Methodology | Key Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boonyanet and Promsen (2018) | Whether KAMs in new audit reports provide informative value to investors. | Performed univariate, correlations, and multivariate regression models with stock prices in 3 periods of analysis of the top 100 Thai listed companies (SET 100) in the Stock Exchange of Thailand. | KAMs have little informative value to investors. Also suggest that the KAMs relating to a provision for doubtful debt have a positive and significant relationship to stock prices. |

| Boonlert-U-Thai and Suttipun (2023) | Explore the content of KAMs collected from the listed companies on the SET and examine the effect of auditor and audit committee characteristics on KAMs reporting. | KAMs reporting on 200 companies in SET during the years 2017 to 2020 were tested by balanced panel analysis. | 1.96 issues of KAMs were reported per year on average. They found the positive effect of audit fees, female auditor, the number of audit committee, and meeting frequency on KAMs reporting, while expertise of audit committee has a negative influent on KAMs reporting. There is no effect of audit firm type, auditor’s rotation, and independent audit committee on KAMs reporting. |

| Chinpuvadol and Boonyanet (2020) | Gap on auditing between auditors and financial statements’ users focusing on auditors’ roles and responsibilities, understanding of auditor’s report, auditor independence and auditor’s liability. | Survey research using questionnaires as data collection tool. Both descriptive and inferential statistics; Mann-Whitney U Test, are used to analyses the data. | Users of the financial statements have higher audit expectations than the auditors in all matters, particularly their understanding of the auditor’s report, including roles and responsibilities of the auditor. Significant difference gap is the understanding of the auditor’s report. Users expected the auditor to disclose the audit method in the auditor’s report. Auditor is likely to issue a material audit to reduce the responsibility of making a material misstatement. |

| Intagool et al. (2020) | Communication value of Key Audit Matters reported in auditor’s report. | 2 aspects (readability and tone) were considered as communication value by gathering from auditor’s reports and financial statements of companies in service industry listed on The SET during 2015–2017, resulting in 304 observations. | The results showed that auditor’s reports with Key Audit Matters was more readable than which without Key Audit Matters. However, the tone of both forms of auditor’s reports is not different. |

| Kanno and Penwuttikul (2018a) | Seeking for a factor concerning auditor towards disclosure quality in KAM and auditor’s report. | 319 auditors, using both descriptive and inferential statistics. | Factor of KAM had resulted in disclosure quality of auditor’s report, the factor of KAM in confidence supply of KAM impacted on disclosure quality. |

| Kanno and Penwuttikul (2018b) | Challenges of auditors’ professionalism towards the changes in the new auditor’s report. | Review literature | The professional auditing of auditor was very crucial and the communication of KAM helped auditor to understand the audited financial statements to make a decision for auditing and expressing ideas on KAM. |

| Kamwass et al. (2020) | Disclosure of KAMs in the auditors’ report and to study the relationship between the disclosure of KAMs and enterprise market value of the Thai listed companies from 2016 to 2017. | 95 company | KAM was revealed using a schedule rather than a lecture. Revenue recognition is the most frequently reported KAM topic. The most important reason to consider KAM is the complex estimate that is made by management. Relationship between KAMs Disclosure and Market Value showed that disclosure of doubtful debt and confirmation techniques were positive. But disclosing goodwill and inventory impairment was a negative correlation. |

| Kitiwong and Sarapaivanich (2020) | Whether the implementation of the expanded auditor’s report, including the KAMs in Thailand since 2016, has improved audit quality. | Examined audit quality two years before and two years after its adoption by analyzing 1519 firm year observations obtained from 312 companies. The authors applied logistic regression analyses to the firm-year observations. | It is not clear if the KAM disclosure improves audit quality. This is because auditors put more effort to perform a thorough investigation following the implementation of KAM. The number of disclosed KAMs and the most common types of disclosed KAMs are not associated with audit quality. |

| Meechumnan et al. (2019) | Communication values of KAM of property and construction industrial companies listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand. | 2 aspects (readability and tone) were considered as communication value by gathering from financial statements and audit reports (English version) in B.E. 2558–B.E. 2560 of property and construction industrial companies listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand were analyzed by the Multiple Regression Analysis. | The new version of audit report with KAM was easier to read than the old version without KAM. The negative tone of content was much more presented. KAM was the most significant part with high risk according to the judge of auditor. Audit report with KAM reflect quality of audit in the better way, but the communication values in early years and in the later years were not different. |

| Matheesuwapab (2018) | Explore appropriate format of audit report on KAM, techniques of identifying KAM, trend on KAM, and expected benefits to the auditors. | 119 auditors from Big 4 audit firms. | The auditor found difficulties when facing KAM writing. They believe that KAM can improve internal controls. Thus, the auditor feel that the audit risk has been reduced. |

| Punyaviwat and Boonyanet (2020) | Explore the content of KAMs of possible delisting companies and responses to identified risks mentioned in KAMs in auditor’s reports. | 22 companies (as of 31 December 2019) of the SET. The study uses content analysis based on auditing standards and authors’ experience to scrutinize KAMs information mentioned in auditor’s reports during accounting. | KAMs do not indicate whether these companies would be delisted from the stock exchange or not. Each company’s KAMs varies by its inherent risks and environment. Furthermore, no boiler-plate was found to be used to identify KAMs. |

| Nuntathanakan et al. (2020) | Communication value of KAM of companies in industrials group listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand. | Data collected from financial statement during 2015–2017, companies in industrials group listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand was analyzed by the Multiple Regression Analysis. | The audit report with KAM is easier to read than the audit report without KAM. In the meanwhile, the negative tone of content is presented much more in the audit report with KAM than the audit report without KAM. Therefore, the new version of audit report with KAM has more communication values. |

| Pratoomsuwan and Yolrabil (2020a) | The effects of KAM disclosures in auditors’ reports on auditor liability in cases of fraud and error misstatements using evaluators with audit experience. | 174 professional auditors as participants. | Auditors assess higher auditor liability when misstatements are related to errors rather than when they are related to fraud. KAM disclosures reduce auditor liability only in cases of fraud and not in cases of errors. KAM reduces the negative affective reactions of evaluators, which reduce the assessed auditor liability. |

| Pratoomsuwan and Yolrabil (2020b) | Effects of KAM disclosures in the auditor’s report on auditor legal exposure in cases of fraud and error misstatements. | 133 professional auditors from Big 4 audit firms and 134 MBA students as the participants. | The auditors assess higher auditor liability when misstatement relates to error than when it is connected to fraud. KAM reduces assessed auditor liability only in cases of fraud but not of error. For nonprofessional investor, the auditor liability is rated higher in the case of fraud than for error misstatement. KAM have a no significant impact on auditor liability. |

| Suttipun (2022) | Explore the content of KAMs collected from the listed companies on the MAI and examine the relationship between auditors’ characteristics and KAMs reporting. | KAMs reporting on 168 companies during the years 2016 to 2018 were tested by content analysis and multiple regression. | KAMs were reported 600 words with 1.63 issues per company on average. The KAMs reporting is significantly positively influenced by auditor type and audit fee, while there was no relationship between audit rotation and KAMs reporting. |

| Yarana et al. (2018) | Gather and analyze contents of Key Audit Matters of Thai listed firms, and compare characteristics of KAM in each industry. | The KAM data was collected from auditors’ reports which were disclosed on the website of the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) from the year 2016 to 2017. | The new auditors’ reports from Big 4 audit firms contain more pages than reports from non-Big 4 firms, on average. Top-three rankings of KAM contents during the year 2016 and 2017 are (1) Revenue Recognition, (2) Investment and asset valuation and their impairment, and (3) Inventory Valuation. The most frequently reported KAM contents in each industry are Revenue Recognition. |

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Type of Auditor | 0.8717 | 0.3349 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (2) Audit fee | 15.3952 | 1.0670 | 13.43 | 19.00 |

| (3) Female on board | 0.1738 | 0.1277 | 0.00 | 0.56 |

| (4) Audit independence | 0.8395 | 1.4221 | 0.05 | 8.86 |

| (5) Year | 2018 | 1.4163 | 2016 | 2020 |

| (6) ROA | 7.5683 | 6.8383 | −29.40 | 32.43 |

| (7) Risk | 0.4715 | 0.2085 | 0.07 | 0.95 |

| (8) Size | 23.9666 | 1.7563 | 20.26 | 27.36 |

| (9) Industry | 3.9767 | 2.0072 | 1.00 | 7.00 |

| KAMs Issue | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 | 16 | 13 | 19 | 21 | 90 |

| 2 | 25 | 26 | 35 | 30 | 26 | 142 |

| 3 | 19 | 19 | 13 | 13 | 16 | 80 |

| 4 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 25 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 69 | 69 | 68 | 69 | 68 | 343 |

| Average | 2.09 | 2.28 | 2.15 | 2.19 | 2.19 | 2.08 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Type of Auditor | 1 | |||||||

| (2) Audit fee | −0.069 | 1 | ||||||

| (3) Female on board | −0.114 * | −0.376 ** | 1 | |||||

| (4) Audit independence | −0.177 ** | −0.233 ** | 0.296 ** | 1 | ||||

| (5) Year | −0.432 ** | 0.139 ** | 0.499 ** | 0.423 ** | 1 | |||

| (6) ROA | −0.278 ** | −0.028 | 0.379 ** | 0.432 ** | 0.317 ** | 1 | ||

| (7) Risk | 0.040 | −0.049 | 0.003 | 0.079 | −0.114 * | −0.056 | 1 | |

| (8) Size | −0.251 ** | 0.452 ** | 0.442 ** | 0.132 * | 0.234 ** | 0.377 ** | −0.253 ** | 1 |

| (9) KAMs | 0.054 | 0.317 ** | 0.024 | 0.119 * | 0.016 | 0.114 * | 0.234 ** | 0.209 ** |

| Coefficients | Standard Error | t Stat | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −4.405 | 1.275 | −3.455 | 0.001 ** |

| Type of auditor | −0.934 | 0.260 | −3.586 | 0.000 ** |

| Audit fee | 0.578 | 0.097 | 5.928 | 0.000 ** |

| Female on board | 0.731 | 0.468 | 1.562 | 0.119 |

| Audit independence | −0.138 | 0.062 | −2.230 | 0.026 * |

| Year | −0.033 | 0.038 | −0.861 | 0.390 |

| ROA | −0.014 | 0.008 | −1.646 | 0.101 |

| Risk | 0.640 | 0.344 | 1.858 | 0.064 |

| Size | −0.085 | 0.055 | −1.548 | 0.123 |

| Industry | 0.101 | 0.032 | 3.138 | 0.002 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Srisuwan, P.; Swatdikun, T.; Pathak, S.; Surbakti, L.P.; Saramolee, A. Factors Influencing Key Audit Matter Reporting in the Stock Exchange of Thailand: Empirical Evidence from 2016–2020 Data. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2024, 17, 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17110512

Srisuwan P, Swatdikun T, Pathak S, Surbakti LP, Saramolee A. Factors Influencing Key Audit Matter Reporting in the Stock Exchange of Thailand: Empirical Evidence from 2016–2020 Data. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2024; 17(11):512. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17110512

Chicago/Turabian StyleSrisuwan, Praphada, Trairong Swatdikun, Shubham Pathak, Lidya Primta Surbakti, and Alisara Saramolee. 2024. "Factors Influencing Key Audit Matter Reporting in the Stock Exchange of Thailand: Empirical Evidence from 2016–2020 Data" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 17, no. 11: 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17110512

APA StyleSrisuwan, P., Swatdikun, T., Pathak, S., Surbakti, L. P., & Saramolee, A. (2024). Factors Influencing Key Audit Matter Reporting in the Stock Exchange of Thailand: Empirical Evidence from 2016–2020 Data. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(11), 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17110512