Factors Influencing Sustainable Poverty Reduction: A Systematic Review of the Literature with a Microfinance Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

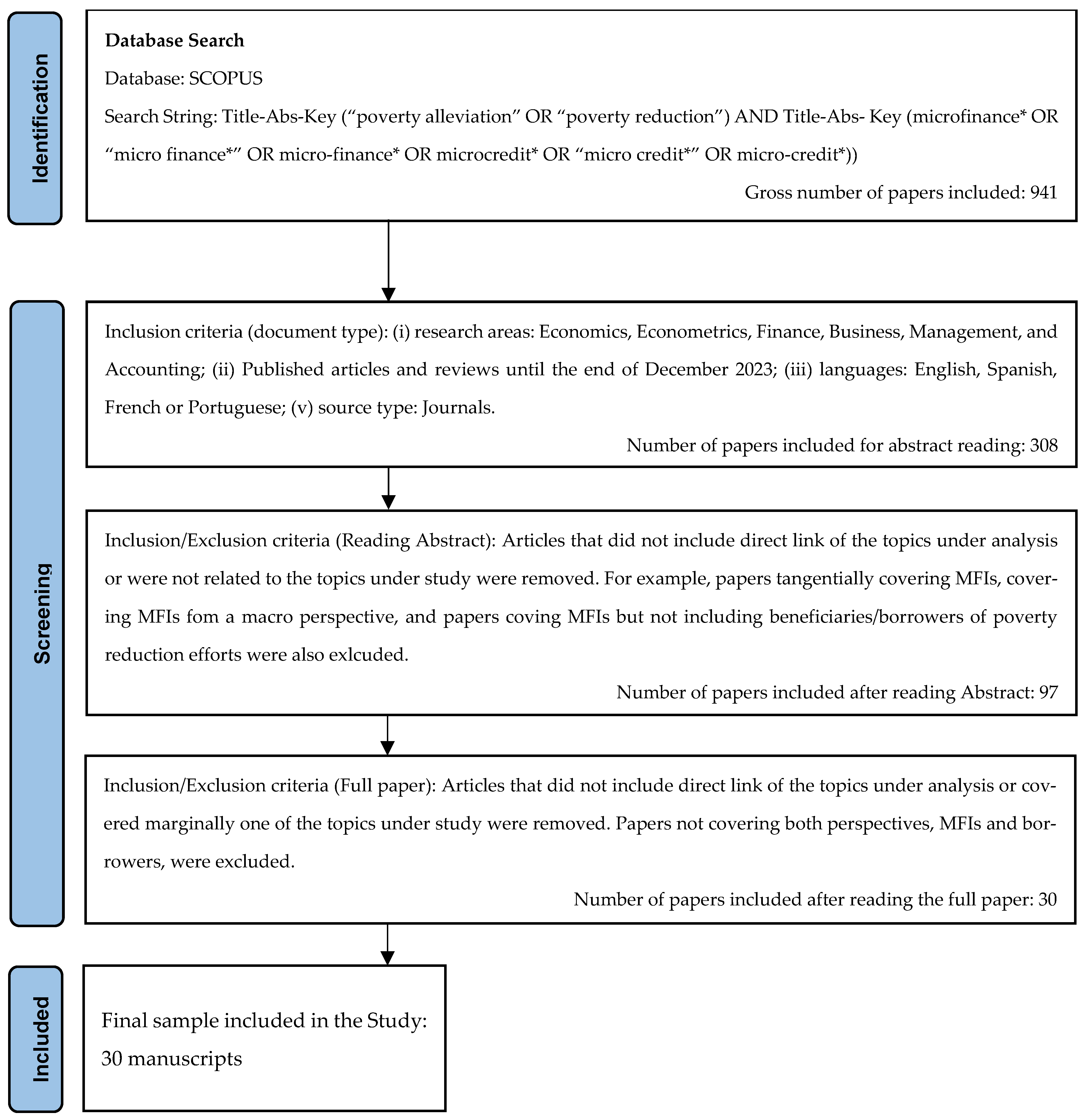

2. Methodology

3. Results

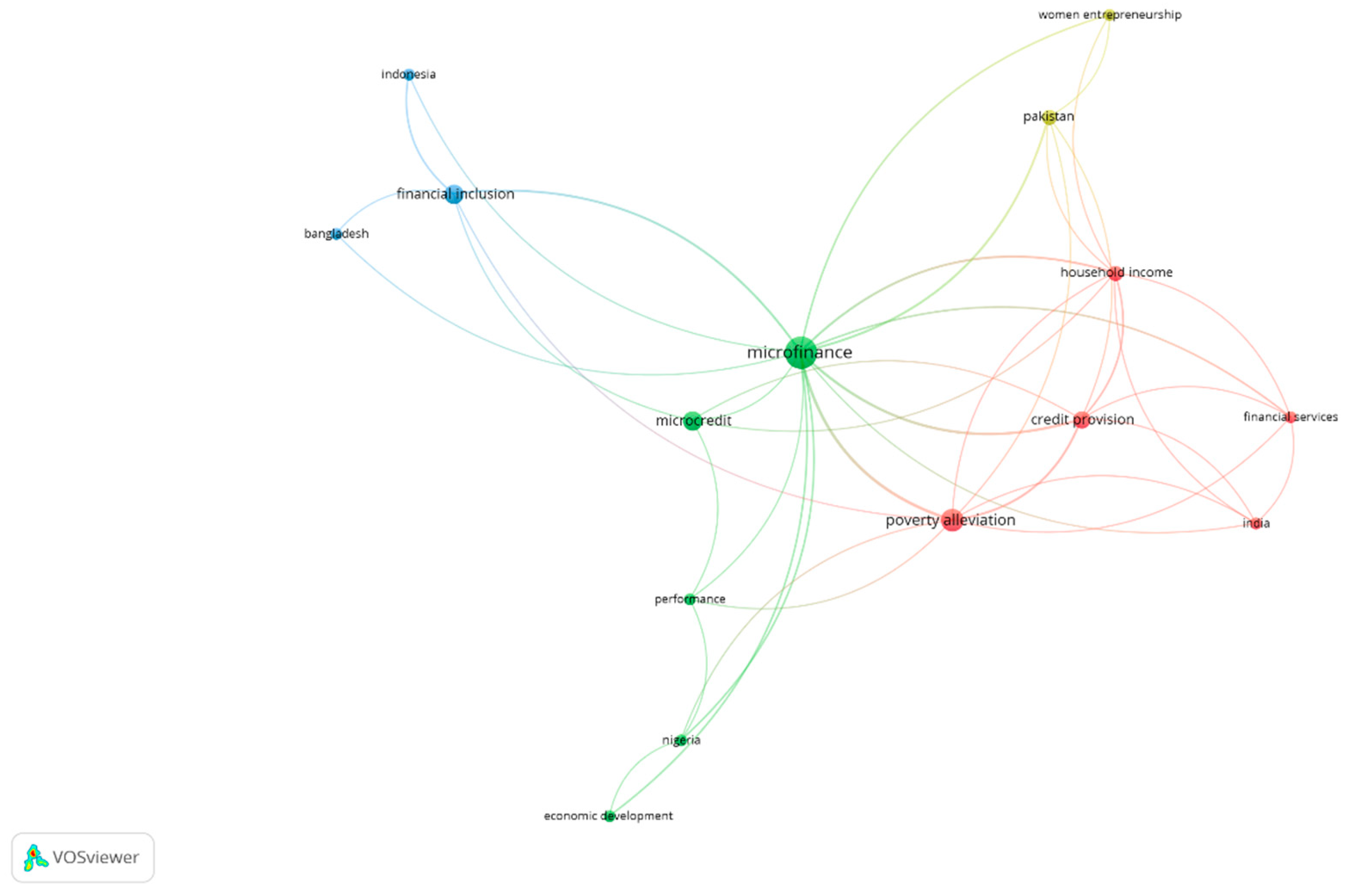

3.1. Co-Occurrence Analysis of Keywords

- Cluster 1 (Red): This cluster comprises five terms: credit provision, financial services, household income, India, and poverty alleviation. The strong correlations within this cluster highlight the close association between poverty alleviation and factors such as credit provision and household income.

- Cluster 2 (Green): This cluster includes five terms: economic development, microcredit, microfinance, Nigeria, and performance. The co-occurrence of these terms suggests a strong relationship between microfinance and factors contributing to poverty reduction, such as microcredit and positive performance leading to economic development.

- Cluster 3 (Blue): This cluster consists of three terms: Bangladesh, financial inclusion, and Indonesia. The close proximity of these terms indicates a connection between financial inclusion and countries like Bangladesh and Indonesia.

- Cluster 4 (Gold): This cluster includes two terms: Pakistan and women entrepreneurship. The co-occurrence suggests a potential relationship between women entrepreneurship and Pakistan.

3.2. Bibliographic Coupling: Document as a Unit of Analysis

3.3. Coverage over Time, Main Outlets, Authors, and Authors’ Geographic Distribution

4. Discussion

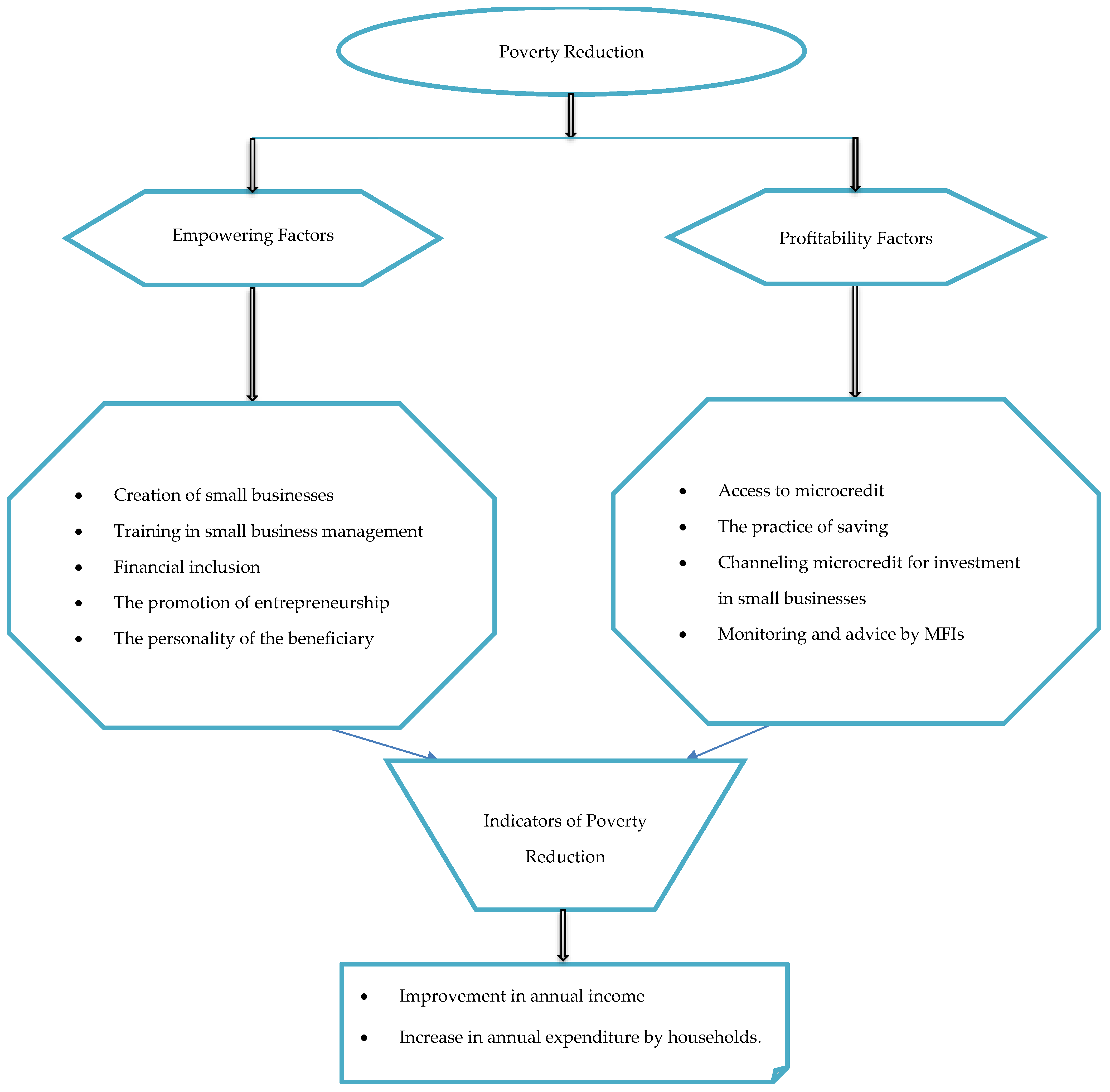

- Integrated Approach to Empowerment and Profitability: Unlike previous studies that have often examined empowerment or profitability factors in isolation, this article integrates them. It recognizes that both sets of factors are essential for achieving poverty reduction.

- Comprehensiveness: Some prior research has focused solely on specific aspects, such as empowerment or profitability, without considering their interplay in the context of poverty reduction (Lensink and Pham 2012; Tasos et al. 2020; Dzingirai 2021). This paper takes a more comprehensive approach, acknowledging the importance of both factors in achieving sustained poverty reduction.

- Unified Framework with Measurement Indicators: Earlier studies have typically not provided a unified view of these factors or offer measurement indicators to assess their impact on poverty reduction (e.g., Aslam et al. 2020; Chikwira et al. 2022; Félix and Belo 2019; Lacalle-Calderon et al. 2018; Tundui and Tundui 2020). This SLR not only identifies the factors but also presents a unified framework with corresponding measurement indicators to gauge their effectiveness in gradually and consistently reducing poverty.

- One of the gaps identified in the literature is the need for a comprehensive framework to understand the factors contributing to poverty mitigation. Previous studies have often examined each of these factors individually, without considering their interconnectedness. When analyzing the impact of microfinance on poverty reduction, it is crucial to consider these factors in an integrated manner, reflecting their inherent relationships and combined effects. This SLR addresses this issue by presenting an integrated framework that groups and categorizes the factors contributing to sustainable poverty reduction. Moreover, it consolidates these factors with relevant indicators to measure their impact on the lives of microfinance beneficiaries, providing a cohesive and comprehensive analysis within a unified interface.

5. Conclusions, Implications, Limitations, and Future Research

6. Implications, Limitations, and Future Research

- Identification and Categorization of Poverty Reduction Factors: This study has successfully identified and categorized factors contributing to poverty reduction within the context of microfinance. It distinguishes between empowerment factors, which equip beneficiaries with essential skills and capabilities, and profitability factors, which enable income generation and improved financial stability.

- Classification into Empowerment and Profitability Groups: This categorization provides a structured approach for understanding the multifaceted nature of poverty reduction in microfinance. Empowerment factors address the underlying causes of poverty, while profitability factors address the immediate financial needs.

- Development of an Integrated Framework: This study introduces an integrated framework that incorporates these factors and their corresponding measurement indicators. This framework offers a comprehensive perspective on poverty reduction within the microfinance context, facilitating a holistic approach to program design and evaluation.

- Intersection of Finance and Development Economics: This research bridges the gap between development economics and financial management by exploring how microfinance—a financial tool—can contribute to sustainable poverty reduction. The integration of financial mechanisms into development strategies is crucial for building inclusive financial ecosystems that support economic growth and sustainability.

- Focus on Financial Inclusion: The core of this research lies in examining microfinance as a means to enhance financial inclusion. By providing financial services to underserved populations, microfinance institutions play a pivotal role in creating responsive and inclusive financial ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, Salehuddin. 2009. Microfinance institutions in Bangladesh: Achievements and challenges. Managerial Finance 35: 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, Shabiha, Md Hamid Uddin, and Ahmad Tajuddin. 2021. Knowledge Mapping of Microfinance Performance Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. International Journal of Social Economics 48: 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, Abera, and Zerhun Ganewo. 2023. Impact Analysis of Formal Microcredit on Income of Borrowers in Rural Areas of Sidama Region, Ethiopia: A Propensity Score Matching Approach. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 14: 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhammadi, Salah. 2023. Expanding Financial Inclusion in Indonesia through Takaful: Opportunities, Challenges and Sustainability. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aninze, Festus, Hatem El-Gohary, and Javed Hussain. 2018. The Role of Microfinance to Empower Women: The Case of Developing Countries. International Journal of Customer Relationship Marketing and Management 9: 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, S., A. Anand, V. V. Anand, V. Rengarajan, and M. Shyam. 2016. Empowering rural women through microfinance: An empirical study. Indian Journal of Science and Technology 9: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, Muhammad, Rab Lodhi, Farhan Sarwar, and Muhammad Ashfaq. 2023. Dark Side Whitewashes the Benefits of FinTech Innovations: A Bibliometric Overview. International Journal of Bank Marketing 42: 113–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, Mohammad, Senthil Kumar, and Shahryar Sorooshian. 2020. Impact of Microfinance on Poverty: Qualitative Analysis for Grameen Bank Borrowers. International Journal of Financial Research 11: 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, Jeroen, Michiel Schotten, Andrew Plume, Grégoire Côté, and Reza Karimi. 2020. Scopus as a Curated, High-quality Bibliometric Data Source for Academic Research in Quantitative Science Studies. Quantitative Science Studies 1: 377–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettoni, Luis, Marcelo Santos, and Gilberto Oliveira Filho. 2023. The Impact of Microcredit on Small Firms in Brazil: A Potential to Promote Investment, Growth and Inclusion. Journal of Policy Modeling 45: 592–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, Imran Sharif. 2009. Poverty alleviation in southern Punjab (Pakistan): An empirical evidence from the project area of Asian Development Bank. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics 1: 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chavriya, Shubham, Gagan Sharma, and Mandeep Mahendru. 2023. Financial Inclusion as a Tool for Sustainable Macroeconomic Growth: An Integrative Analysis. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 95: 527–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikwira, Collin, Edson Vengesai, and Petronella Mandude. 2022. The Impact of Microfinance Institutions on Poverty Alleviation. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, Tiken. 2023. Microfinance and Poverty Reduction in Assam: Uncovering the Nexus between Access to Credit and Household Well-being. Space and Culture, India 11: 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, Srimoyee, and Tarak Nath Sahu. 2022. How Far is Microfinance Relevant for Empowering Rural Women? An Empirical Investigation. Journal of Economic Issues 56: 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denyer, David, and David Tranfield. 2009. Producing a Systematic Review. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods. Edited by David Buchanan and Alan Bryman. New York: Sage Publications Ltd., pp. 671–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dhungana, Bharat, Ramkrishna Chapagain, and Arvind Ashta. 2023. Alternative Strategies of For-profit, Not-for-profit and State-owned Nepalese Microfinance Institutions for Poverty Alleviation and Women Empowerment. Cogent Economics and Finance 11: 2233778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzingirai, Mufaru. 2021. The Role of Entrepreneurship in Reducing Poverty in Agricultural Communities. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 15: 665–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, Elisabete, and Teresa Belo. 2019. The Impact of Microcredit on Poverty Reduction in Eleven Developing Countries in South-east Asia. Journal of Multinational Financial Management 52–53: 100590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, James, Joel Greer, and Erik Thorbecke. 1984. A Class of Decomposable Poverty Measures. Econometrica 52: 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginanjar, Adhitya, and Salina Kassim. 2020. Can Islamic Microfinance Alleviates Poverty in Indonesia? an Investigation From the Perspective of the Microfinance Institutions. Journal of Islamic Monetary Economics and Finance 6: 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gora, Kapil, Barkha Dhingra, and Mahender Yadav. 2023. A bibliometric study on the role of micro-finance services in micro, small and medium enterprises. Competitiveness Review 34: 718–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Morshadul, Thi Le, and Ariful Hoque. 2021. How does Financial Literacy Impact on Inclusive Finance? Financial Innovation 7: 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M. Kabir, Muhammed Islam, Zobayer Ahmed, and Jahidul Sarker. 2023. Islamic banking in Bangladesh: A literature review and future research agenda. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 16: 1030–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, Nik, and Zuraimi Aziz. 2021. Socioeconomic Development on Poverty Alleviation of Women Entrepreneurship. International Journal of Professional Business Review 6: e0283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, Katsushi, Thankom Arun, and Samuel Kobina Annim. 2010. Microfinance and Household Poverty Reduction: New Evidence from India. World Development 38: 1760–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaka, Emmanuel, and Faudziah Abidin. 2014. Poverty Alleviation in the Northeast Nigeria Mediation of Performance and Moderating Effect of Microfinance Training: A Proposed Framework. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5: 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kasali, Taofeek, Siti Ahmad, and Hock Lim. 2015. The Role of Microfinance in Poverty Alleviation: Empirical Evidence From South-West Nigeria. Asian Social Science 11: 183–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Arshad, Sufyan Khan, Shah Fahad, Muhammad Ali, Aftab Khan, and Jianchao Luo. 2021. Microfinance and Poverty Reduction: New Evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Finance & Economics 26: 4723–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, Malcom. 2021. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Research: A Bibliometric Analysis Over a 50-year Period. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacalle-Calderon, Maricruz, Manuel Perez-Trujillo, and Isabel Neira. 2018. Does Microfinance Reduce Poverty among the Poorest? A Macro Quantile Regression Approach. Developing Economies 56: 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lensink, Robert, and Thi Pham. 2012. The Impact of Microcredit on Self-employment Profits in Vietnam. Economics of Transition 20: 73–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Xia, Chirstopher Gan, and Baiding Hu. 2011. The Welfare Impact of Microcredit on Rural Households in China. Journal of Socio-Economics 40: 404–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, Samia, Javed Hussain, and Harry Matlay. 2014. Optimal Microfinance Loan Size and Poverty Reduction amongst Female Entrepreneurs in Pakistan. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 21: 231–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, Shrabanti. 2023. Financial Inclusion also Leads to Social Inclusion—Myth or Reality? Evidences from Self-help Groups Led Microfinance of Assam. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 12: 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, Mohummed, and Wencong Lu. 2013. Micro-credit and Poverty Reduction: A Case of Bangladesh. Prague Economic Papers 22: 403–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, and Douglas Altman. 2010. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. International Journal of Surgery 8: 336–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota, Jorge, Antonio Moreira, and Cristovão Brandão. 2018. Determinants of Microcredit Repayment in Portugal: Analysis of Borrowers, Loans and Business Projects. Portuguese Economic Journal 17: 141–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, Jorge, Antonio Moreira, Rui Costa, Silvana Serrão, Vera Pais-Magalhães, and Carlos Costa. 2020. Performance Indicators to Support Firm-level Decision-making in the Wine Industry: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Wine Business Research 33: 217–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, Raina, and Peterson Ozili. 2023. Reimagining Financial Inclusion in the Post COVID-19 World: The Case of Grameen America. International Journal of Ethics and Systems 39: 532–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumu, Jinnatul, Tahani Tahmid, and Md. Abdul Azad. 2021. Job Satisfaction and Intention to Quit: A Bibliometric Review of Work-family Conflict and Research Agenda. Applied Nursing Research 59: 151334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nargis, Farhana. 2019. Poverty Reduction and Human Development: Impact of ENRICH Programme on Income Poverty in Bangladesh. Indian Journal of Human Development 13: 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaz, Muhammad. 2022. Socio-Economic Development and Sustainable Development Goals: A Roadmap from Vulnerability to Sustainability through Financial Inclusion. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja 35: 3243–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, Mark, and Helen Roberts. 2008. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Pactical Guide. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, Hugo, Belem Barbosa, Antonio Moreira, and Ricardo Rodrigues. 2022. Churn in Services—A Bibliometric Review. Cuadernos de Gestion 22: 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslan, Abdul-Hakim, and Mohd Zaini Abd Karim. 2009. Determinants of Microcredit Repayment in Malaysia: The Case of Agrobank. Humanity & Social Science Journal 4: 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sashi, C. M. 2011. The Make-buy Decision in Marketing Financial Services for Poverty Alleviation. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 15: 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, Amartya. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Šeric, Maja, and Mario Šeric. 2021. Sustainability in Hospitality Marketing during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Content Analysis of Consumer Empirical Research. Sustainability 13: 10456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Brett, Joshua Knapp, and Benedetto Cannatelli. 2022. Entrepreneurship at the Base of the Pyramid: The Moderating Role of Person-Facilitator Fit and Poverty Alleviation. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 13: 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasos, Stylianou, Muhammad Amjad, Masood Awan, and Muhammad Waqas. 2020. Poverty Alleviation and Microfinance for the Economy of Pakistan: A Case Study of Khushhali Bank in Sargodha. Economies 8: 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, John G., and Xiaoyun Li. 2012. China’s changing poverty: A middle income country case study. Journal of International Development 24: 696–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdell, Clement, and Shabbir Ahmad. 2018. Microfinance: Economics and Ethics. International Journal of Ethics and Systems 34: 372–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tundui, Charles, and Hawa Tundui. 2020. Performance Drivers of Women-owned Microcredit Funded Enterprises in Tanzania. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 12: 211–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Program. 2006. Human Development Report 2006. In United Nations Development Program. London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2022. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2022: Correcting Course. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Yihua, Fanchen Meng, Muhammad Farrukh, Ali Raza, and Imtiaz Alam. 2023. Twelve Years of Research in The International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management: A Bibliometric Analysis. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 16: 154–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, Muhammad-Bashir Owolalbi, Nasim Shah Shirazi, and Gairuzazmi Mat Ghani. 2013. The impact of Pakistan poverty alleviation fund on poverty in Pakistan: An empirical analysis. Middle East Journal of Scientific Research 13: 1335–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description | Results |

|---|---|

| Documents | 30 |

| Sources | 30 |

| Time span | 2010:2023 |

| Annual growth rate (%) | 16.15% |

| Document average age | 5.03 |

| Average citations per article | 18.2 |

| References | 1726 |

| Authors | 70 |

| Authors of single-authored articles | 7 |

| Authors of multi-authored articles | 23 |

| Single-authored articles | 7 |

| Co-authors per article | 2.33 |

| International co-authorships % | 33.33% |

| Years | Number of Articles | Percentage (%) | Cumulative Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 7 | 23.3 | 23.3 |

| 2022 | 4 | 13.3 | 36.7 |

| 2021 | 4 | 13.3 | 50.0 |

| 2020 | 4 | 13.3 | 63.3 |

| 2019 | 2 | 6.7 | 70.0 |

| 2018 | 1 | 3.3 | 73.3 |

| 2015 | 1 | 3.3 | 76.7 |

| 2014 | 2 | 6.7 | 83,3 |

| 2013 | 1 | 3.3 | 86.7 |

| 2012 | 1 | 3.3 | 90.0 |

| 2011 | 2 | 6.7 | 96.7 |

| 2010 | 1 | 3.3 | 100.00 |

| Total | 30 | 100% | 100% |

| Authors | Geographical Coverage | Source | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Imai et al. 2010) | India | World Development | 182 |

| (Hasan et al. 2021) | Capital (Dhaka) and the other two industrially developed cities (Gazipur and Narayongonj), Bangladesh | Financial Innovation | 63 |

| (Li et al. 2011) | Collected through a household survey in rural China | Journal of Socio-Economics | 56 |

| (Mahmood et al. 2014) | Pakistan | Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development | 45 |

| (Khan et al. 2021) | Pakistan | International Journal of Finance and Economics | 28 |

| (Lensink and Pham 2012) | Vietnam | Economics of Transition | 27 |

| (Félix and Belo 2019) | Bangladesh, Cambodia, East Timor, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand, and Sri Lanka | Journal of Multinational Financial Management | 24 |

| (Niaz 2022) | - | Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja | 21 |

| (Lacalle-Calderon et al. 2018) | - | Developing Economies | 20 |

| (Sashi 2011) | - | Journal of Financial Services Marketing | 10 |

| (Kasali et al. 2015) | South-West Nigeria | Asian Social Science | 8 |

| (Datta and Sahu 2022) | Districts of West Bengal, India | Journal of Economic Issues | 9 |

| (Hussin and Aziz 2021) | Three different states in Malaysia | International Journal of Professional Business Review | 9 |

| (Mazumder and Lu 2013) | Bangladesh | Prague Economic Papers | 8 |

| (Tundui and Tundui 2020) | Tanzania | International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship | 8 |

| (Chikwira et al. 2022) | Zimbabwe | Journal of Risk and Financial Management | 8 |

| (Tasos et al. 2020) | The district of Sargodha, Pakistan | Economies. | 8 |

| (Dzingirai 2021) | Zimbabwean agricultural communities | Journal of Enterprising Communities | 7 |

| (Maity 2023) | Districts of Assam, India | Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship. | 4 |

| (Aslam et al. 2020) | - | International Journal of Financial Research | 3 |

| (Ginanjar and Kassim 2020) | The Islamic microfinance institutions (IMFIs) in Indonesia. | Journal of Islamic Monetary Economics and Finance | 3 |

| (Alemu and Ganewo 2023) | Rural areas of Sidama Region, Ethiopia. | Journal of the Knowledge Economy | 2 |

| (Mousa and Ozili 2023) | United States of America | International Journal of Ethics and Systems | 2 |

| (Smith et al. 2022) | - | Journal of Social Entrepreneurship | 1 |

| (Nargis 2019) | Bangladesh | Indian Journal of Human Development | 1 |

| (Bettoni et al. 2023) | Brazil | Journal of Policy Modeling | 1 |

| (Alhammadi 2023) | Takaful, Indonesia | Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting | 1 |

| (Kaka and Abidin 2014) | North-East Nigeria | Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences | 0 |

| (Das 2023) | Valley of Assam, India | Space and Culture, India | 0 |

| (Dhungana et al. 2023) | Strategies of MFIs in Nepal | Cogent Economics and Finance | 0 |

| Authors | Poverty Reduction—Empowering Factors | Poverty Reduction—Profitability Factors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training in Small Business Management | Financial Inclusion | Entrepreneurship/Small Business | The Mindset of the Beneficiary | Access to Microcredit | Monitoring and Advice by MFIs | Saving/Investment Practice | |

| (Alemu and Ganewo 2023) | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| (Alhammadi 2023) | √ | ||||||

| (Aslam et al. 2020) | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| (Bettoni et al. 2023) | √ | ||||||

| (Chikwira et al. 2022) | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| (Das 2023) | √ | √ | |||||

| (Datta and Sahu 2022) | √ | √ | |||||

| (Dhungana et al. 2023) | √ | ||||||

| (Dzingirai 2021) | √ | √ | |||||

| (Félix and Belo 2019) | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| (Ginanjar and Kassim 2020) | √ | ||||||

| (Hasan et al. 2021) | √ | ||||||

| (Hussin and Aziz 2021) | √ | √ | |||||

| (Imai et al. 2010) | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| (Kaka and Abidin 2014) | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| (Kasali et al. 2015) | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| (Khan et al. 2021) | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| (Lacalle-Calderon et al. 2018) | √ | ||||||

| (Lensink and Pham 2012) | √ | ||||||

| (Li et al. 2011) | √ | √ | |||||

| (Mahmood et al. 2014) | √ | √ | |||||

| (Maity 2023) | √ | ||||||

| (Mazumder and Lu 2013) | √ | √ | |||||

| (Mousa and Ozili 2023) | √ | ||||||

| (Nargis 2019) | √ | √ | |||||

| (Niaz 2022) | √ | √ | |||||

| (Sashi 2011) | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| (Smith et al. 2022) | √ | ||||||

| (Tasos et al. 2020) | √ | ||||||

| (Tundui and Tundui 2020) | √ | √ | √ | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fonseca, S.; Moreira, A.; Mota, J. Factors Influencing Sustainable Poverty Reduction: A Systematic Review of the Literature with a Microfinance Perspective. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2024, 17, 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17070309

Fonseca S, Moreira A, Mota J. Factors Influencing Sustainable Poverty Reduction: A Systematic Review of the Literature with a Microfinance Perspective. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2024; 17(7):309. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17070309

Chicago/Turabian StyleFonseca, Salvador, António Moreira, and Jorge Mota. 2024. "Factors Influencing Sustainable Poverty Reduction: A Systematic Review of the Literature with a Microfinance Perspective" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 17, no. 7: 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17070309

APA StyleFonseca, S., Moreira, A., & Mota, J. (2024). Factors Influencing Sustainable Poverty Reduction: A Systematic Review of the Literature with a Microfinance Perspective. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(7), 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm17070309