Heterogeneous Links Between Corruption and Innovation in a Global Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

The Main Hypotheses

3. Data and Main Variables

Main Variables

4. Institutional Quality, Corruption, and Innovation: Some Stylized Facts

5. Estimation Strategy

5.1. Results

5.2. Alternative Methods

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

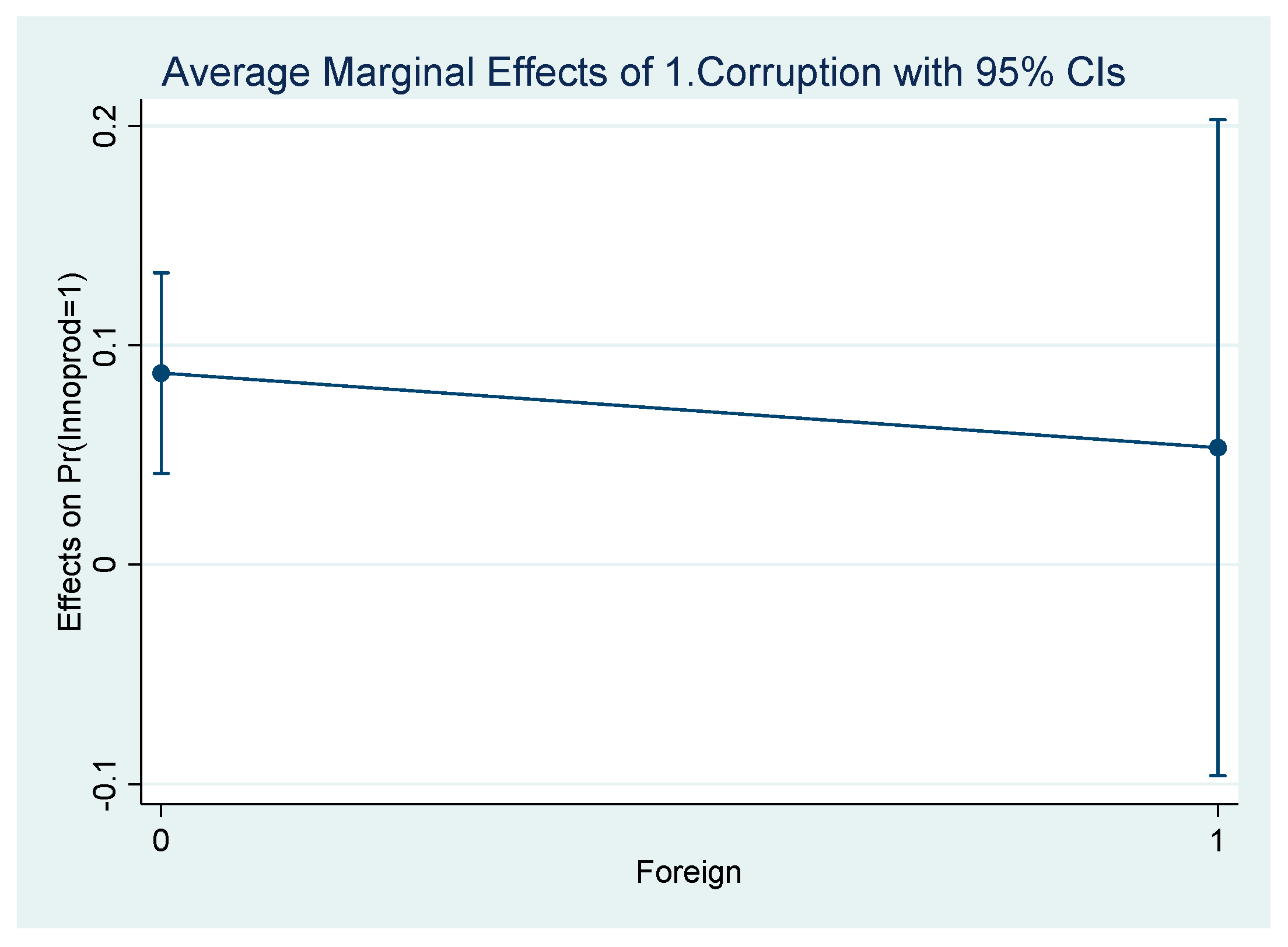

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Countries | Number of Firms | % Innovative Firms (Product) | % Firms Paying Bribes | % Foreign Firms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | 152 | 23.36 | 21.21 | 8.22 |

| Belarus | 158 | 35.24 | 4.41 | 12.66 |

| Bosnia and Herz. | 151 | 43.67 | 6.20 | 7.28 |

| Croatia | 71 | 39.44 | 6.82 | 7.75 |

| Estonia | 63 | 29.37 | 2.04 | 11.11 |

| Georgia | 110 | 25.45 | 0 | 5.91 |

| Kazakhstan | 140 | 17.69 | 9.13 | 2.86 |

| Kosovo | 78 | 48.08 | 7.69 | 0 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 147 | 40.29 | 32.76 | 19.34 |

| Latvia | 90 | 40.00 | 1.99 | 14.44 |

| Lithuania | 75 | 30.14 | 3.91 | 4.00 |

| Moldova | 142 | 32.16 | 7.75 | 8.80 |

| Mongolia | 172 | 36.63 | 16.87 | 4.65 |

| Montenegro | 69 | 21.01 | 12.50 | 8.70 |

| Poland | 194 | 31.95 | 7.04 | 4.12 |

| Russia | 400 | 16.94 | 8.44 | 3.12 |

| Serbia | 145 | 38.54 | 6.93 | 9.31 |

| Slovenia | 78 | 54.25 | 6.87 | 16.03 |

| Tajikistan | 115 | 19.65 | 10.81 | 4.35 |

| Turkey | 609 | 11.08 | 3.39 | 2.79 |

| Ukraine | 168 | 33.23 | 27.34 | 5.36 |

| Uzbekistan | 170 | 11.50 | 1.88 | 12.35 |

| TOTAL | 3.584 | 26.27 | 8.40 | 6.61 |

| Countries | 2013 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| Albania | −0.70 | −0.52 |

| Belarus | −0.47 | −0.19 |

| Bosnia and Herz. | −0.24 | −0.57 |

| Croatia | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| Estonia | 1.19 | 1.51 |

| Georgia | 0.47 | 0.71 |

| Kazakhstan | −0.93 | −0.50 |

| Kosovo | −0.65 | −0.52 |

| Kyrgyzstan | −1.16 | −0.95 |

| Latvia | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| Lithuania | 0.43 | 0.50 |

| Moldova | −0.75 | −0.73 |

| Mongolia | −0.48 | −0.43 |

| Montenegro | −0.25 | 0.02 |

| Poland | 0.60 | 0.64 |

| Russia | −1.01 | −0.85 |

| Serbia | −0.30 | −0.37 |

| Slovenia | 0.73 | 0.87 |

| Tajikistan | −1.28 | −1.42 |

| Turkey | −0.09 | −0.34 |

| Ukraine | −1.26 | −0.87 |

| Uzbekistan | −1.26 | −1.07 |

| Variable Name | Kind of Variable | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Country Group | Categorical | 1. The establishment is located in one of the following countries: Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Poland, or Slovenia. 2. The establishment is located in one of the following countries: Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Albania, Kosovo, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Georgia, or Turkey. 3. The establishment is located in one of the following countries: Russia, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, or Mongolia. |

| Innoprod | Binary | 1 = In the last three years, the establishment has introduced new products or services. 0 = otherwise |

| FirmCorruption | Binary | 1 = In the last three years, the establishment has paid an informal payment “to get things done”. 0 = otherwise |

| Controlcorr | Continuous | Value of the Control of Corruption index of the country where the firm is located (See Table A2) |

| Foreign | Binary | 1. Ten percent of the firm is owned by private foreign individuals, companies or organizations. 0. Otherwise |

| Competition | Ordered categorical | 1. Low: in the last fiscal year, in the market where the establishment sells its main product, it faced from 0 to 5 competitors. 2. Medium: the establishment faced more than 5 competitors (but still countable) 3. High: the establishment faced uncountable competitors (“too many to count”). |

| RD | Binary | 1. In the last three years, the firm has spent money on R&D activities, either in-house or contracted with other companies (outsourced). 0. Otherwise |

| Train | Binary | 1. In the last fiscal year, the establishment had formal training programs for its permanent, full-time employees. 0. Otherwise |

| Fortech | Binary | 1. The establishment uses technology licensed from a foreign-owned company, excluding office software. 0. Otherwise |

| Export | Binary | 1. In the last fiscal year, a positive percentage of the establishment’s sales are direct or indirect exports. 0. Otherwise |

| Size | Continuous | Natural logarithm of the number of employees. |

| Wave | Binary | 1. Survey VI 0. Survey V |

| 1 | Transparency International defines corruption as; the abuse of entrusted power for private gain https://www.transparency.org/en/what-is-corruption (accessed on 12 March 2025); and bribery is a subset of corruption defined as the offering, promising, or giving of something to influence an official. Corrupt transactions can be extremely simple or extremely complex. They include both grand (political) and petty (administrative) corruption, as well as organized and disorganized corruption. In any case, no definition of corruption is fully clearly-cut. It also has many different interpretations, varying over time and context as well as by discipline. Notwithstanding the differences in definition between corruption and bribery, in this work we use the two terms as synonymous. |

| 2 | Among the 50 micro-level empirical studies analyzed by Martins et al. (2020) focusing mostly on single countries, 31 studies have concluded that corruption (mostly bribery) is harmful to firm performance, whereas 19 suggest the opposite. |

| 3 | Bahoo et al. (2021) in the bibliometric analysis of the literature on corruption in the discipline of economics between 1968–2019 identify seven streams of the literature. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | Original data can be downloaded at the link https://www.beeps-ebrd.com/data/ (Last accessed by the authors on 12 March 2025). |

| 6 | From the perspective of their locations and histories, the three groupings of nations -based on their ranking of their control over corruption- appear to align closely: all the countries in the sample that are part of the European Union, along with Georgia, are categorized in CountryGroup 1. Meanwhile, all countries from the former Soviet Union, except for Belarus (which ranks significantly higher in terms of control over corruption) and the Baltic states (which share much of their history with Western Europe), are placed in CountryGroup 3. |

| 7 | The choice of control variables has been spearheaded by the literature in this area: size, R&D investments, foreign ownership, competition, and exporting are also included by Krammer (2019) as control variables; Karaman Kabadurmus and Sylwester (2022) include licenses for foreign technology. |

| 8 | The complete question, numbered E2 in the Questionnaire, is: “In regard to the main market to which this establishment sold its main product, how many competitors did this establishment’s main product face?” |

| 9 | 5 is chosen because it is the median among the firms declaring a countable number of competitors. |

| 10 | Country dummy variables are not utilized, because their inclusion would prevent evaluating the effects of the between variability of Controlcorr. |

| 11 | Weighted mean of the Control of Corruption for each country reported by the Worldwide Governance Indicator of the World Bank Group. Data by country are reported in Table A2 in the Appendix A. The range for Control of Corruption is from −2.5 (minimum control of corruption) to +2.5 (maximum control, of corruption), Weights are the number of firms for each country included in the sample. |

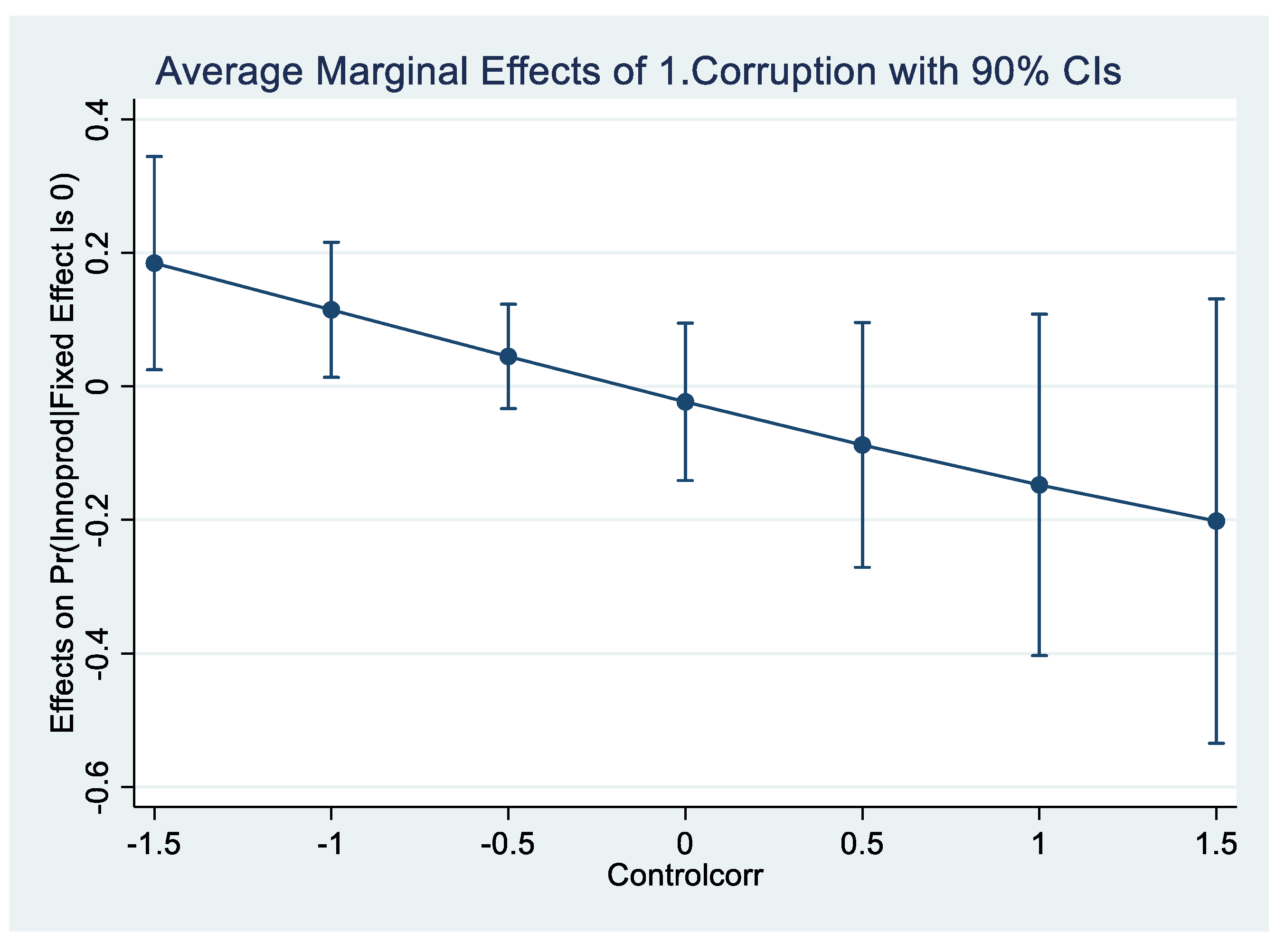

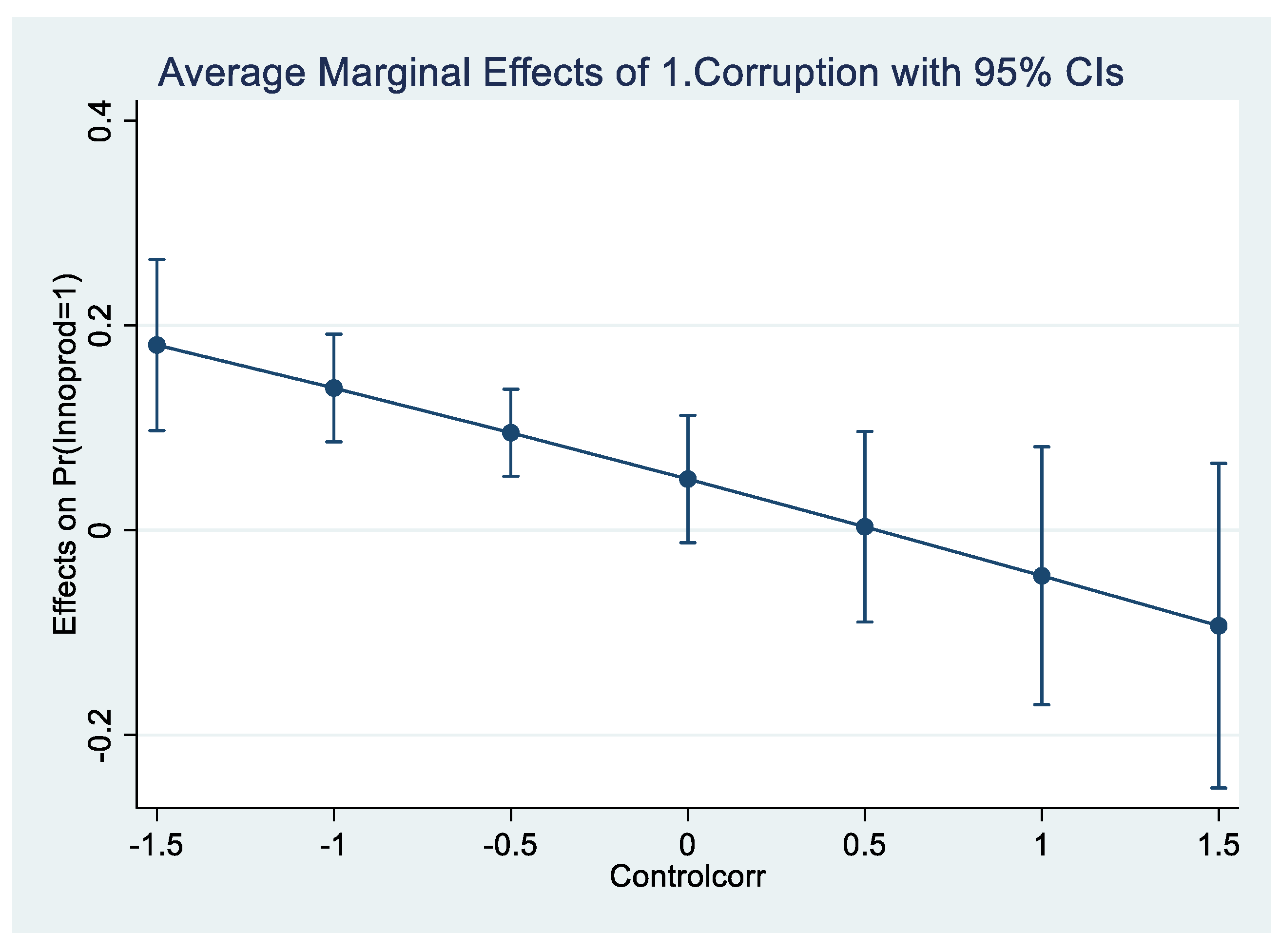

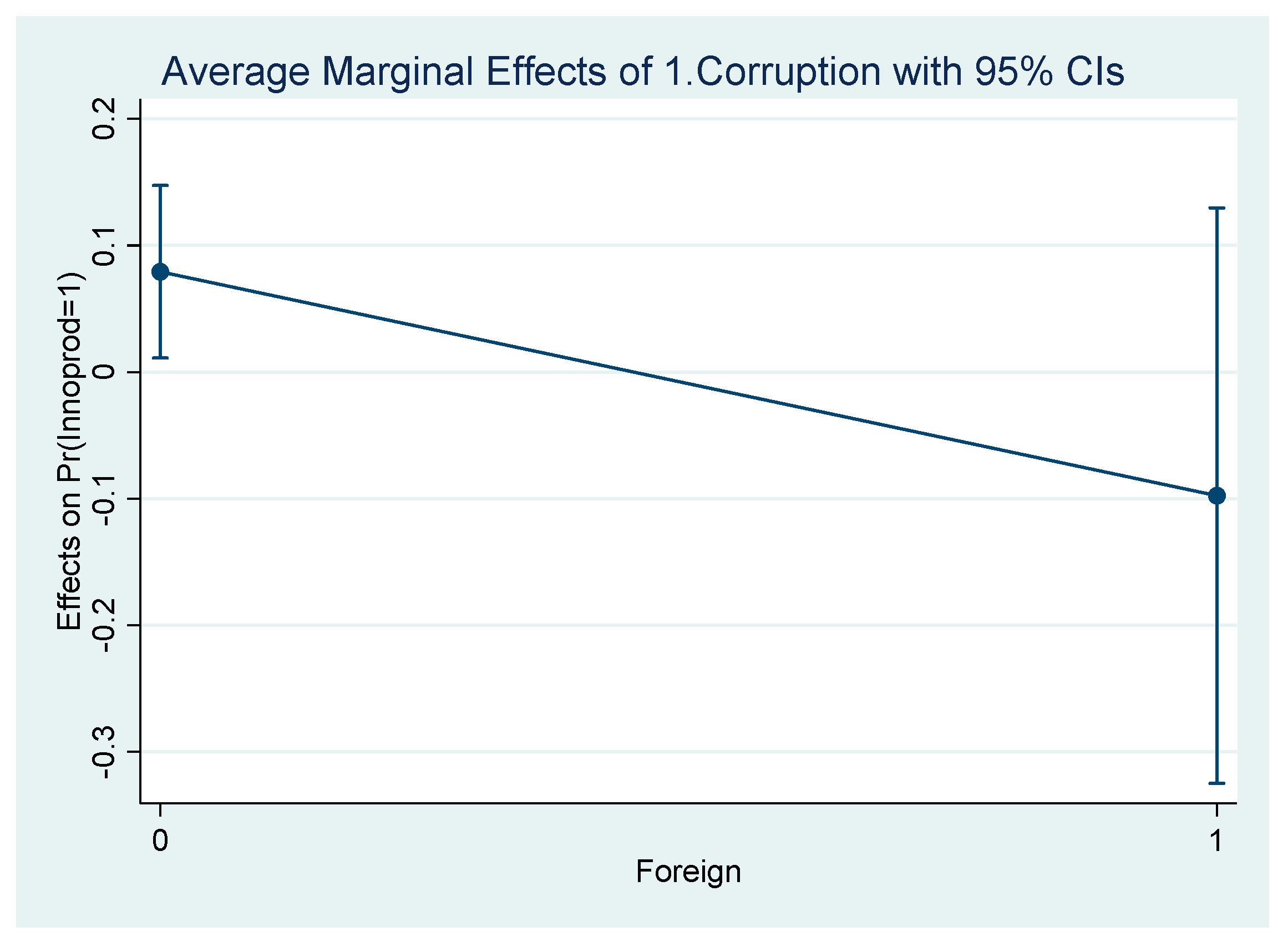

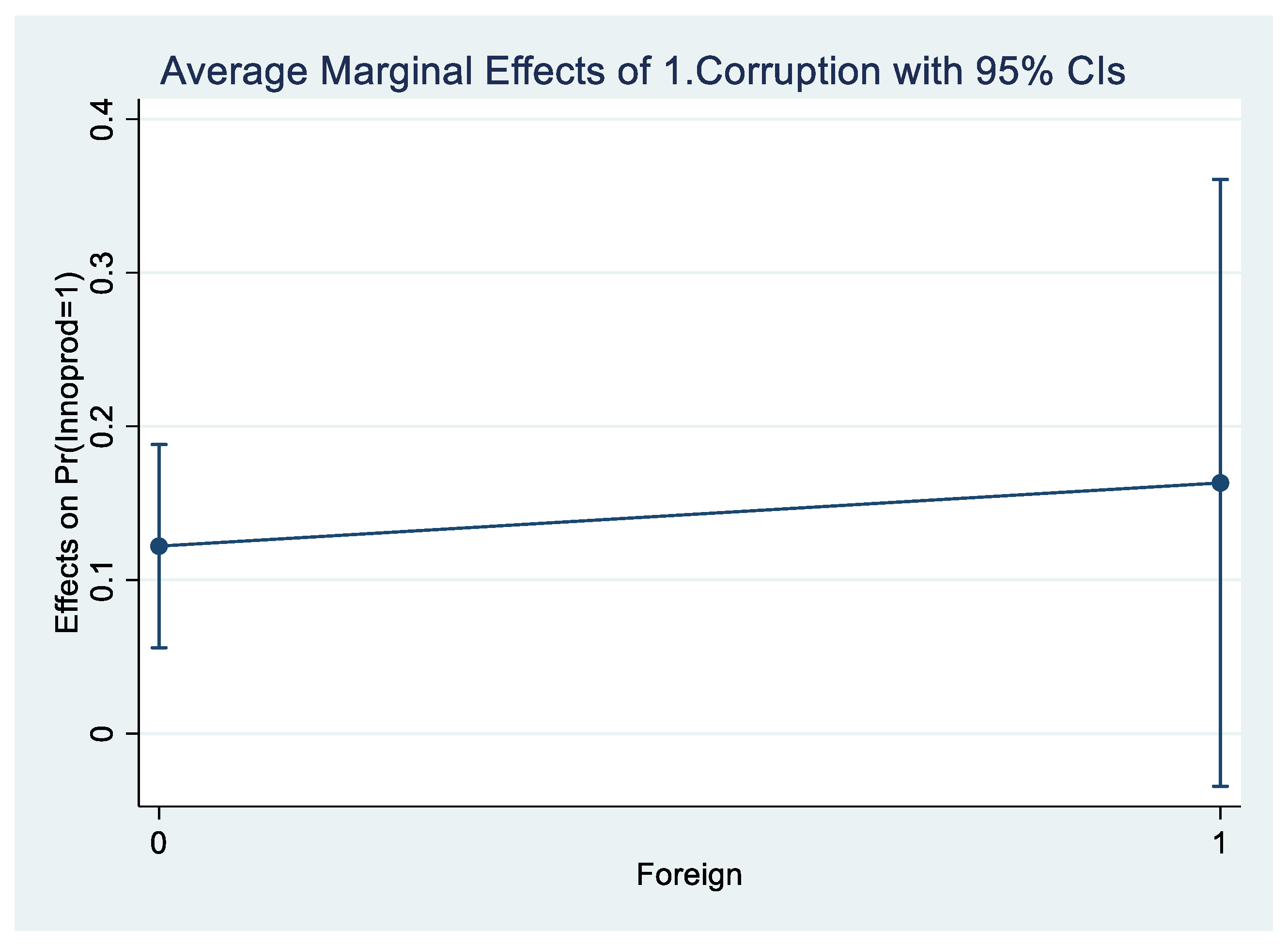

| 12 | The 95% confidence intervals do not overlap when comparing the lowest and highest Controlcorr levels, indicating that the decreasing effect of FirmCorruption as Controlcorr increases is statistically significant at a level of 5%. |

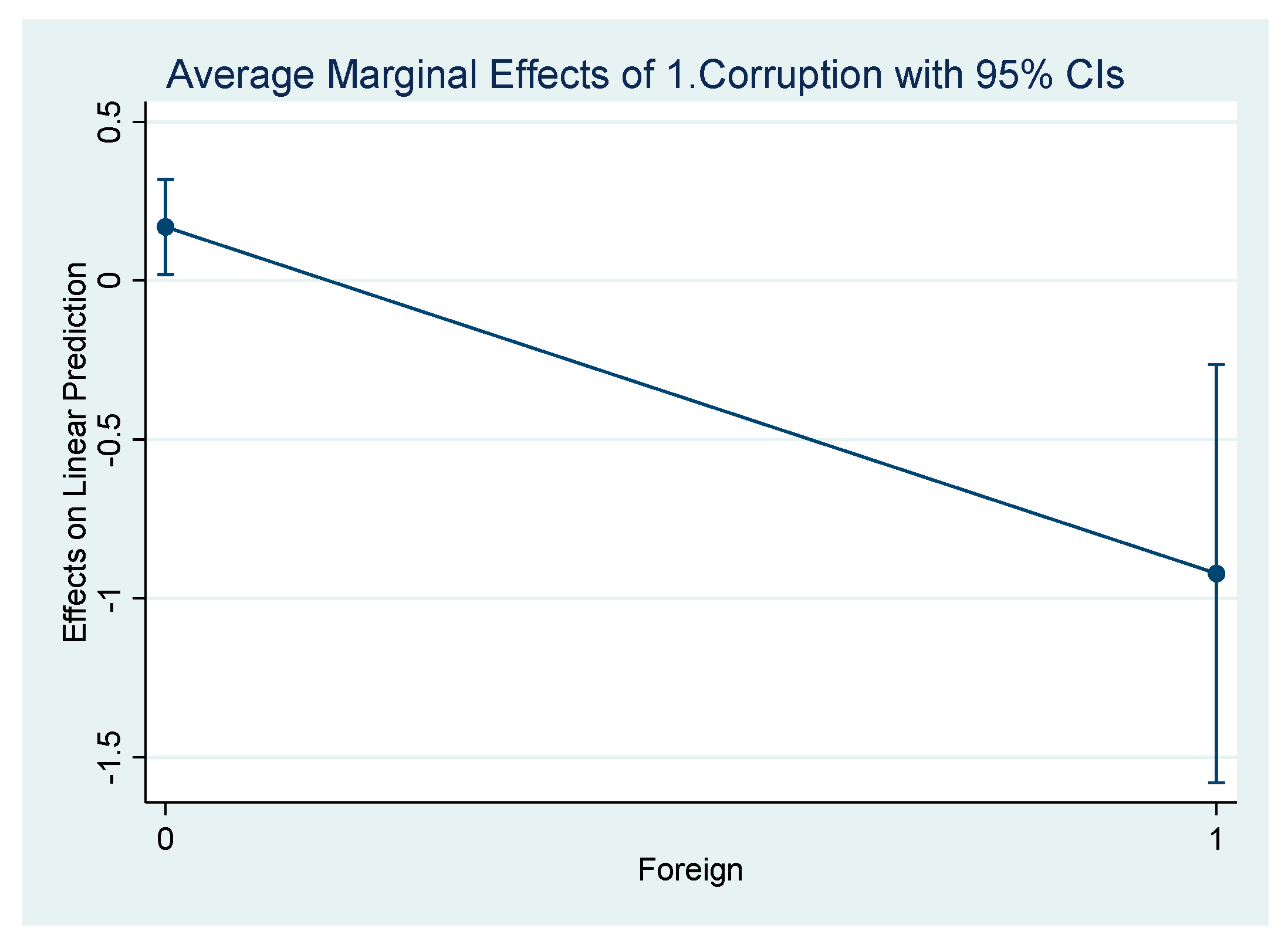

| 13 | Results of probit model are more reliable than results of linear probability model. Nevertheless, due to the limited number of cases, probit model was not estimable in CountryGroup 1. |

| 14 | According to the probit model, this result is very close to the 10% significance threshold: p = 0.103. |

| 15 | These findings hold regardless of the composition and size of country groups. We estimated a model incorporating a triple interaction between FirmCorruption, Controlcorr, and Foreign across the entire sample. The estimated marginal effect of FirmCorruption on innovation was then computed for both domestic and foreign firms at different levels of Control of Corruption (high, intermediate, and low). The results remain consistent with previous findings. |

| 16 | The likelihood ratio test of rho = 0 applied on the estimation of the random effect probit model (results in Table 6) is inconclusive (close to 5% threshold) on the importance of panel-level component of variance; hence the legitimacy of non panel probit estimation. |

| 17 | If the non-panel probit model is estimated using ordinary or robust standard errors, the interaction effect between FirmCorruption and Controlcorr is significant at a 5% level. Similarly, the interaction between FirmCorruption and Controlcorr remains significant at 5% when estimated using a linear probability model with standard OLS. Although the linear probability model is generally considered unsuitable for a binary dependent variable, this result is noteworthy in the context of omitted variable issues: as Bun and Harrison (2019) demonstrate, an OLS estimator remains consistent when estimating the interaction between an endogenous and an exogenous variable—where Controlcorr can reasonably be considered exogenous. |

References

- Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashyrov, G., & Masso, J. (2020). Does corruption affect local and foreign-owned companies differently? Evidence from the BEEPS survey. Post-Communist Economies, 32, 306–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasouli, D., & Goujard, A. (2015). Corruption and management practices: Firm level evidence. Journal of Comparative Economics, 43, 1014–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, M., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, A. (2014). Bribe payments and innovation in developing countries: Are innovating firms disproportionately affected? Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 9, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahoo, S., Ilan, A., & Paltrinieri, A. (2021). Corruption in international business: A review and research agenda. International Business Review, 29, 101660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S. R., & Lewellyn, K. B. (2017). Ownership structure and earnings management in emerging markets. An institutionalized agency perspective. International Business Review, 26, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barassi, M. R., & Zhou, Y. (2012). The effect of corruption on FDI: A parametric and non-parametric analysis. European Journal of Political Economy, 28, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughn, C., Bodie, N., Buchanan, M. A., & Bixby, M. B. (2010). Bribery in international business transactions. Journal of Business Ethics, 92, 15–32. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25621541 (accessed on 12 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Boubakri, N., Mansi, S., & Saffar, W. (2013). Political institutions, connectedness, and corporate risk-taking. Journal of International Business Studies, 44, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukari, C., & Atta Anaman, E. (2021). Corruption and firm innovation: A grease or sand in the wheels of commerce? Evidence from lower-middle and upper-middle income economies. Eurasian Business Review, 11, 267–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bun, M. J. C., & Harrison, T. D. (2019). OLS and IV estimation of regression models including endogenous interaction terms. Econometric Reviews, 38, 814–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Cullen, J. B., & Parboteeah, K. B. (2015). Are manager-controlled firms more likely to bribe than shareholder-controlled firms: A cross-cultural analysis. Management and Organization Review, 11, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonnelli, E., & Prem, M. (2022). Corruption and firms. The Review of Economic Studies, 89, 695–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couttenier, M., & Toubal, F. (2017). Corruption for sales. Journal of Comparative Economics, 45, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2006). Who cares about corruption? Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 803–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2016). Corruption in international business. Journal of World Business, 51, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallago, B., & Casagrande, S. (2021). The “new comparative economics”: A critical review. In E. Douarin, & O. Havrylyshyn (Eds.), The palgrave handbook of comparative economics. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J. A., Smith, J. D., & White, R. M. (2020). Corruption and corporate innovation. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 55, 2124–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, L. T., Thanh, T. T., Thang, D. N., & Anh, P. T. H. (2021). Bribery, export decisions, and institutional constraints: Evidence from cross-country firm-level data. Economic Analysis and Policy, 69, 585–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearn, B. (2015). Institutional influences on board composition of international joint venture firms listing on emerging stock exchanges: Evidence from Africa. Journal of World Business, 50, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, T. D., Davis, A. P., & French, M. T. (2020). Limitations of fixed-effects models for panel data. Sociological Perspectives, 63, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorio, R., & Segnana, M. L. (2021). Is paying bribes worthwhile? Corruption and innovation in middle-income countries. Eurasian Business Review, 12, 475–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javorcik, B. S., & Wei, S.-J. (2009). Corruption and cross-border investment in emerging markets: Firm level evidence. Journal of International Money and Finance, 28, 605–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman Kabadurmus, F. N., & Sylwester, K. (2022). Corruption and innovation: The importance of competition. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 17, 766–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keig, D. L., Brouthers, L. E., & Marshall, V. B. (2015). Formal and informal corruption environments and multinational enterprise social irresponsibility. Journal of Management Studies, 52, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krammer, S. M. (2009). Drivers of national innovation in transition: Evidence from a panel of Eastern European countries. Research Policy, 38, 845–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krammer, S. M. (2019). Greasing the wheels of change: Bribery, institutions, and new product introductions in emerging markets. Journal of Management, 45, 1889–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krammer, S. M., & Jimenez, A. (2020). Do political connections matter for firm innovation? Evidence from emerging markets in Central Asia and Eastern Europe. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 151, 119669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krammer, S. M., Strange, R., & Lashitew, A. (2018). The export performance of emerging economy firms: The influence of firm capabilities and institutional environments. International Business Review, 27, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. C., Wang, C. W., & Ho, S.-J. (2020). Country governance, corruption, and the likelihood of firms’ innovation. Economic Modelling, 92, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A., & Froese, F. J. (2022). Corruption as a perverse Innovation: The dark side of digitalization and corruption in international business. Journal of Business Research, 145, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L., Cerdeira, J., & Teixeira, A. (2020). Does corruption boost or harm firms’ performance in developing and emerging economies? A firm-level study. World Economics, 43, 2119–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K., & Peng, M. (2016). Theoretical foundations of emerging economy business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 47, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muellner, J., Klopf, P., & Nell, P. C. (2017). Trojan horses or local allies: Host-country national managers in developing market subsidiaries. Journal of International Management, 23, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N. A., Doan, Q. H., & Nguyen, N. M. (2016). Tran-Nam B. The impact of petty corruption on firm innovation in Vietnam. Crime Law Soc Change, 65, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnsorge, F., & Yu, S. (Eds.). (2021). The long shadow of informality. Challenges and policies. World Bank Publications. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/35782 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Pantzalis, C., Park, J. C., & Sutton, N. (2008). Corruption and valuation of multinational corporations. Journal of Empirical Finance, 15, 387–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P., Uhlenbruck, K., & Eden, L. (2005). Government corruption and the entry strategies of multinationals. Academy of Management Review, 30, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Ackerman, S. (2008). Corruption and government. Journal of International Peacekeeping, 15, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Ackerman, S., & Truex, R. (2012). Corruption and policy reform. Yale Law & Economics Research Paper. No. 444. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2007152 (accessed on 12 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Roy, J. P., & Oliver, C. (2009). International joint venture partner selection: The role of the host-country legal environment. Journal of International Business Studies, 40, 779–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C., & Mitra, A. (2015). Corruption, governance and firm performance: Evidence from Indian enterprises. Journal of Policy Modeling, 37, 835–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thede, S., & Karpaty, P. (2023). Effects of corruption on foreign direct investment: Evidence from Swedish multinational enterprises. Journal of Comparative Economics, 51, 348–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, S. (2012). How (not) to measure institutions. Journal of Institutional Economics, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, S. (2018). How to measure informal institutions. Journal of Institutional Economics, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., & Chen, Y. (2018). Capability stretching in product innovation. Journal of Management, 44, 784–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., & Yang, Z. (2024). Anti-corruption and firm innovation: Political path dependence perspective. Post-Communist Economies, 36, 906–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J., Teng, D., & Meng, S. (2018). Foreign ownership and bribery: Agency and institutional perspectives. International Business Review, 27, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Countries | Number of Firms | |

|---|---|---|

| Country Group 1 | 7 | 1362 |

| Country Group 2 | 8 | 3068 |

| Country Group 3 | 7 | 2738 |

| All countries | 22 | 7168 |

| Control of Corruption (Average) | % Firms Paying a Bribe “to Get Things Done” * | % Innovative Firms ** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country Group 1 | 0.596 | 4.40% | 34.82% |

| Country Group 2 | −0.337 | 7.68% | 25.85% |

| Country Group 3 | −0.982 | 11.41% | 22.50% |

| All countries | −0.375 | 8.40% | 26.27% |

| % Innovative Firms Among Firms Paying Bribes (a) * | % Innovative Firms Among Firms not Paying Bribes (b) ** | “Effect” of Corruption (a)–(b) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country Group 1 | 38.46% | 34.97% | +3.49% |

| Country Group 2 | 35.85% | 24.20% | +11.40% |

| Country Group 3 | 40.32% | 19.61% | +21.19% |

| All countries | 38.30% | 24.75% | +13.55% |

| % Foreign Firms * | % Corruption (Domestic Firms) ** | % Corruption (Foreign Firms) *** | % Innovation (Domestic Firms) **** | % Innovation (Foreign Firms) ***** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country Group 1 | 8.15% | 4.50% | 3.19% | 33.23% | 53.27% |

| Country Group 2 | 5.74% | 7.57% | 9.62% | 25.17% | 36.93% |

| Country Group 3 | 6.83% | 10.71% | 20.65% | 21.12% | 41.40% |

| All countries | 6.61% | 8.12% | 12.35% | 25.13% | 42.43% |

| % Innovative Firms Among Firms Paying a Bribe (a) * | % Innovative Firms Among Firms NOT Paying a Bribe (b) ** | “Effect” of Corruption (a)–(b) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country Group 1 | |||

| Domestic firms | 40.82% | 33.27% | +7.55% |

| Foreign firms | 0.00% | 54.44% | −54.44% |

| Country Group 2 | |||

| Domestic firms | 35.03% | 23.36% | +11.67% |

| Foreign firms | 46.67% | 38.30% | +8.37% |

| Country Group 3 | |||

| Domestic firms | 36.65% | 18.63% | +18.02% |

| Foreign firms | 65.63% | 34.43% | +31.20% |

| All countries | |||

| Domestic firms | 36.40% | 23.65% | +12.75% |

| Foreign firms | 56.00% | 41.08% | +14.92% |

| Variables | MODEL1 (Dependent.Var: Innoprod) |

|---|---|

| FirmCorruption | 0.176 (0.043) |

| Controlcorr | 0.224 *** (0.041) |

| FirmCorruption * Controlcorr | −0.330 ** (0.136) |

| Foreign | 0.272 *** (0.086) |

| Competition_2 | 0.105 (0.055) |

| Competition_3 | −0.378 *** (0.053) |

| R&D | 0.792 *** (0.061) |

| Training | 0.400 *** (0.048) |

| Fortech | 0.203 *** (0.061) |

| Export | 0.243 *** (0.057) |

| Size | 0.027 (0.020) |

| Wave | 0.132 *** (0.043) |

| Industry dummies | Included |

| Constant | −0.518 (0.625) |

| Statistics | |

| Number of observations | 5206 |

| Number of groups (firms) | 3241 |

| Log likelihood | −2519.6499 |

| Wald chi2 Prob > chi2 | (160) 578.38 0.0000 |

| LR test of rho = 0 | Chibar2(01) = 2.50 Prob ≥ chibar(2) = 0.057 |

| Domestic Firms (a) | Foreign Firms (b) | |

|---|---|---|

| Country Group 1 | +0.176 ** | Not estimable |

| +0.170 ** | −0.922 *** | |

| Country Group 2 | +0.079 ** | −0.098 |

| +0.070 ** | −0.093 | |

| Country Group 3 | +0.122 *** | +0.163 |

| +0.119 *** | +0.170 ** | |

| All countries | +0.087 *** | +0.053 |

| +0.086 *** | +0.054 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iorio, R.; Segnana, M.L. Heterogeneous Links Between Corruption and Innovation in a Global Economy. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18030164

Iorio R, Segnana ML. Heterogeneous Links Between Corruption and Innovation in a Global Economy. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(3):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18030164

Chicago/Turabian StyleIorio, Roberto, and Maria Luigia Segnana. 2025. "Heterogeneous Links Between Corruption and Innovation in a Global Economy" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 3: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18030164

APA StyleIorio, R., & Segnana, M. L. (2025). Heterogeneous Links Between Corruption and Innovation in a Global Economy. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(3), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18030164