The Role of Project Description in the Success of Sustainable Crowdfunding Projects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of Crowdfunding and Sustainability

2.2. Factors Influencing Fundraising Success in Crowdfunding

2.3. Role of Project Descriptions in Crowdfunding

2.4. Sustainability in Crowdfunding

3. Methodology

3.1. Analytical Approach and Data Source

3.2. Data Analysis and Model

= β0 + β1length + β2readability + β3goal

+ β4duration + β5year + β6SDGs_kw_count

+ β7avg_basket_value + 𝜖

3.3. Validity of the Research

3.4. Reliability of the Research

4. Empirical Results

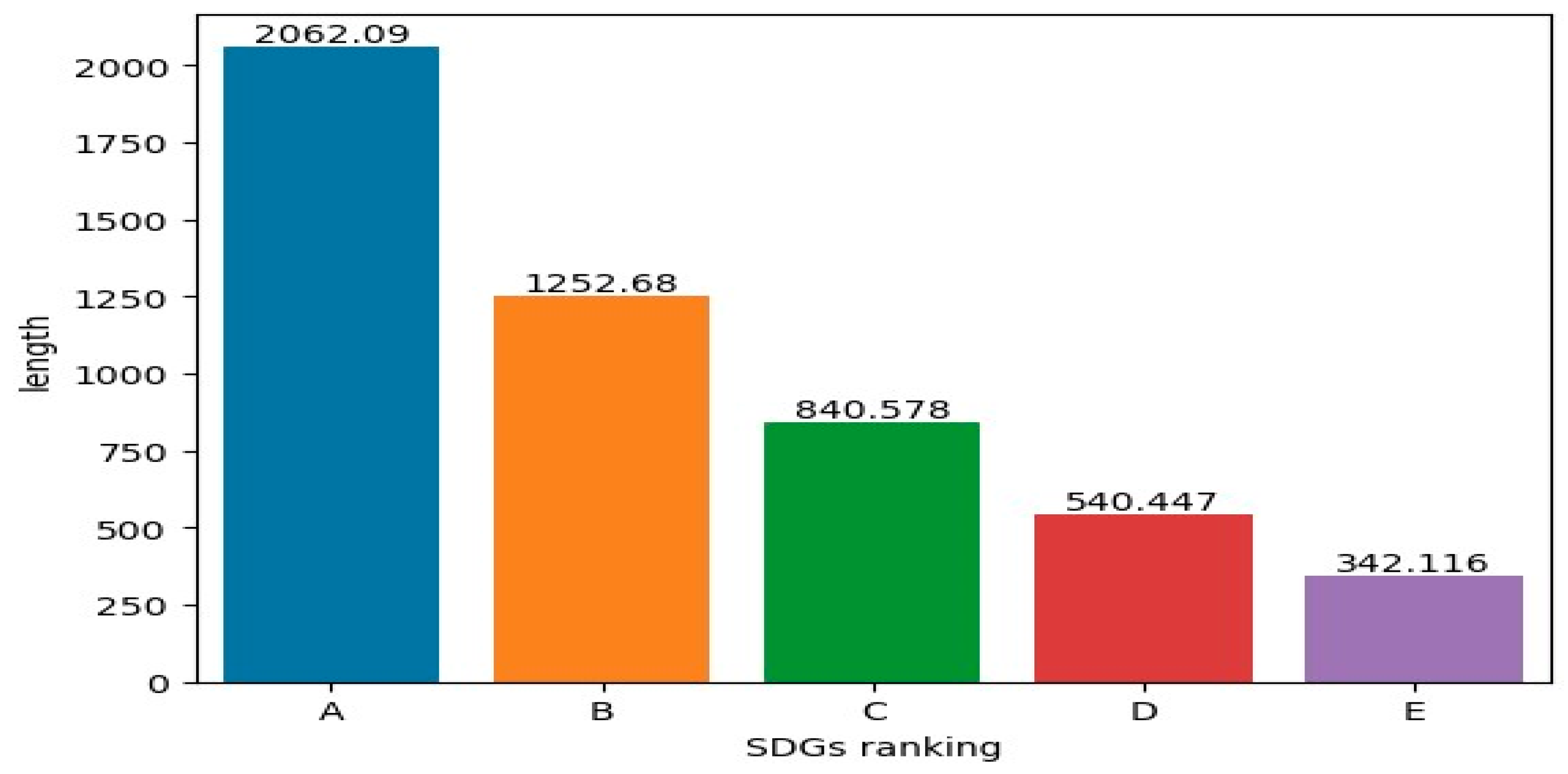

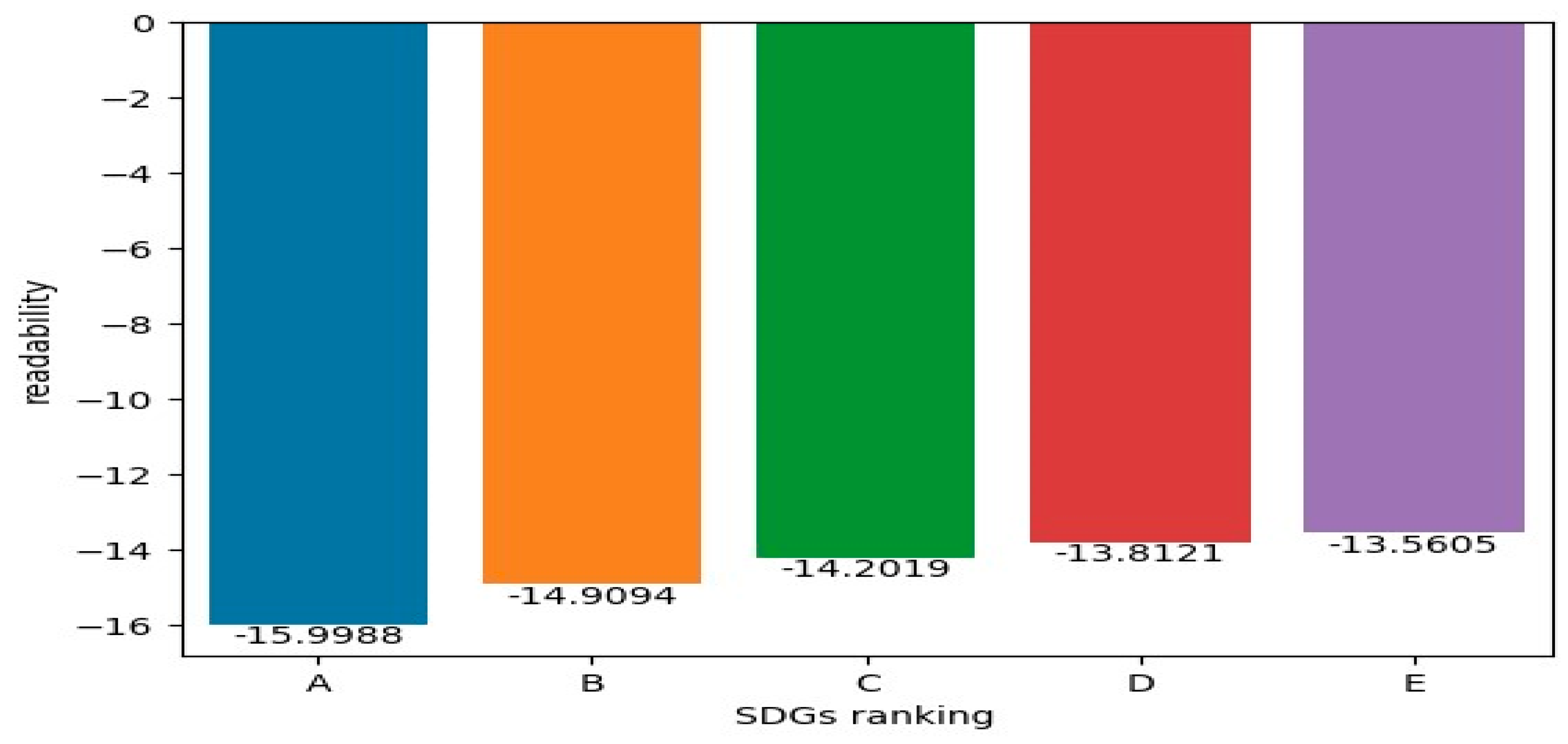

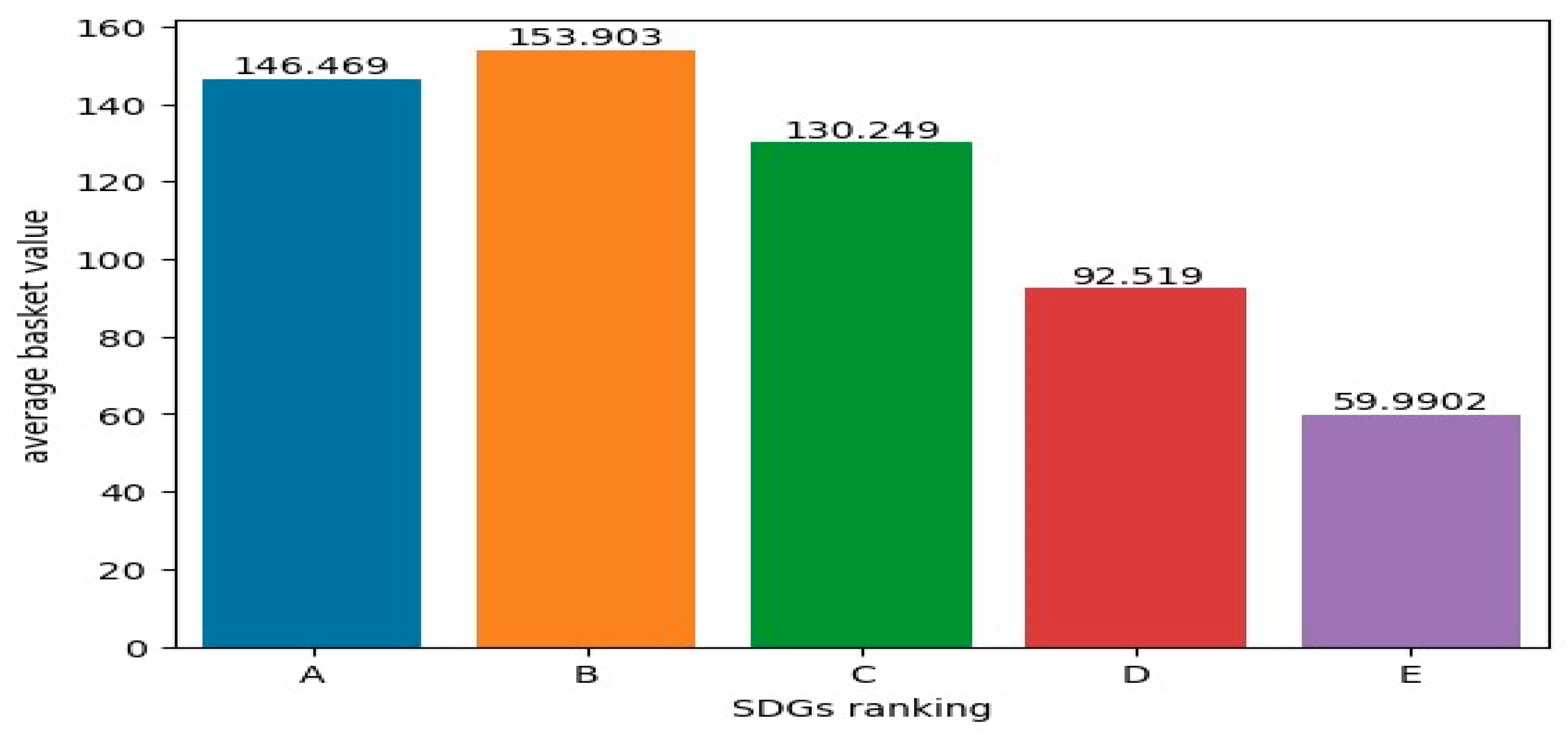

4.1. Descriptive Results

- -

- Group A: Projects with more than 20 different SDG keywords.

- -

- Group B: Projects with 6 to 19 SDG keywords.

- -

- Group C: Projects with three to five SDG keywords.

- -

- Group D: Projects with one or two SDG keywords.

- -

- Group E: Projects with no SDG keywords.

4.2. Logistic Regression Analysis

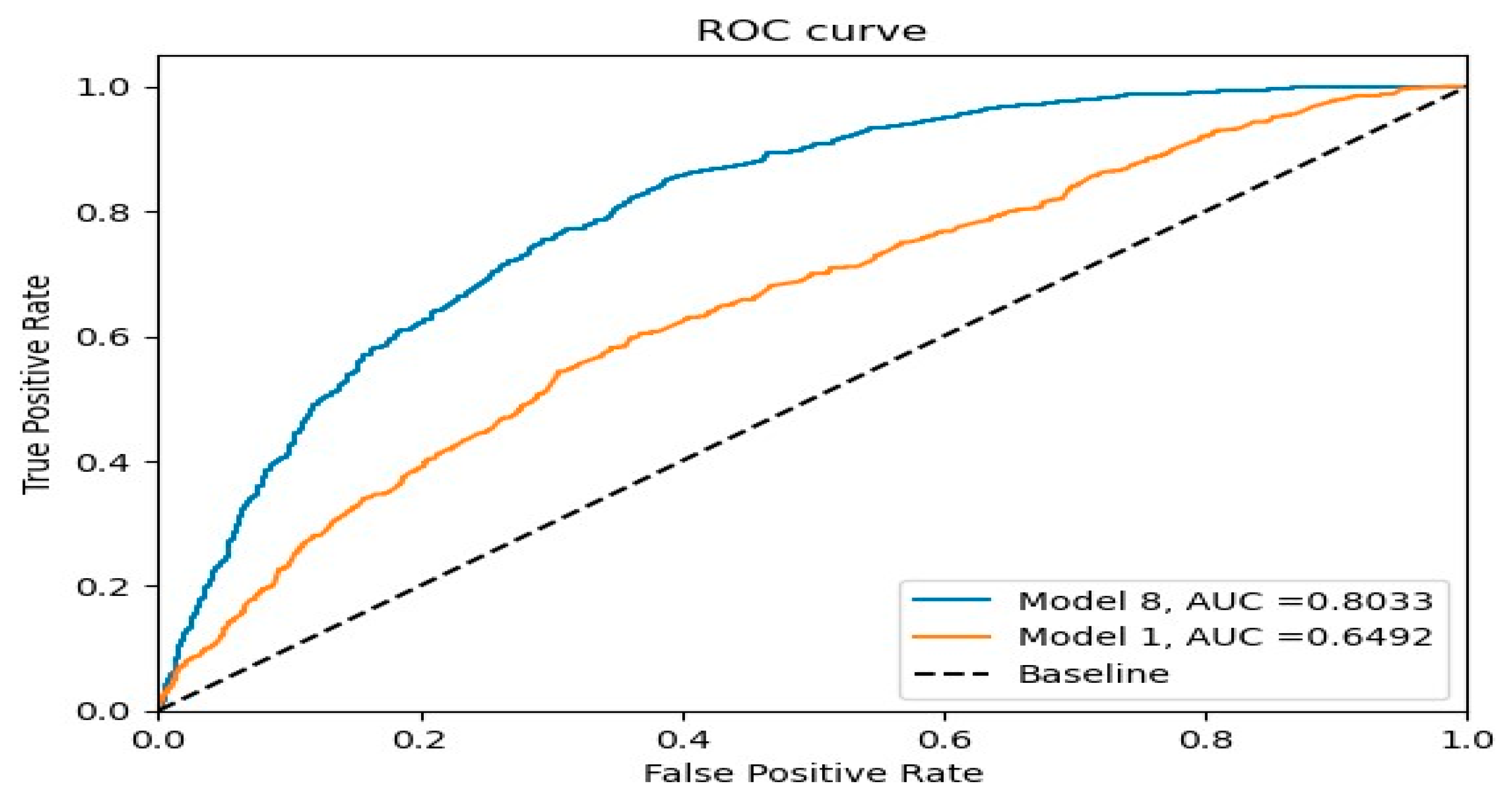

4.3. Evaluation of Predicting Performance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamska-Mieruszewska, J., Mrzygłód, U., Suchanek, M., & Fornalska-Skurczyńska, A. (2021). Keep it simple. The impact of language on crowdfunding success. Economics & Sociology, 14(1), 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, T. H., Davis, B. C., Short, J. C., & Webb, J. W. (2015). Crowdfunding in a prosocial microlending environment: Examining the role of intrinsic versus extrinsic cues. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(1), 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Battilana, J., & Lee, M. (2014). Advancing research on hybrid organizing–Insights from the study of social enterprises. Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 397–441. [Google Scholar]

- Belleflamme, P., Lambert, T., & Schwienbacher, A. (2014). Crowdfunding: Tapping the right crowd. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(5), 585–609. [Google Scholar]

- Belz, F. M., & Binder, J. K. (2017). Sustainable entrepreneurship: A convergent process model. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Böckel, A., Hörisch, J., & Tenner, I. (2021). A systematic literature review of crowdfunding and sustainability: Highlighting what really matters. Management Review Quarterly, 71, 433–453. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, A. P. (1997). The use of the area under the ROC curve in the evaluation of machine learning algorithms. Pattern Recognition, 30(7), 1145–1159. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. E., Boon, E., & Pitt, L. F. (2017). Seeking funding in order to sell: Crowdfunding as a marketing tool. Business Horizons, 60(2), 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkett, E. (2011). A crowdfunding Exemption-Online investment crowdfunding and US Secrutiies regulation. Transactions: The Tennessee Journal of Business Law, 13, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Calic, G., & Mosakowski, E. (2016). Kicking off social entrepreneurship: How a sustainability orientation influences crowdfunding success. Journal of Management Studies, 53(5), 738–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H. F., Moy, N., Schaffner, M., & Torgler, B. (2021). The effects of money saliency and sustainability orientation on reward based crowdfunding success. Journal of Business Research, 125, 443–455. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B., Luo, Y., Li, J., Li, Y., Liu, Y., Yang, F., Bo, J., & Qiao, Y. (2023). Blockchain-based decentralized co-governance: Innovations and solutions for sustainable crowdfunding. arXiv, arXiv:2306.00869. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. S., & Chang, C. H. (2012). Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. Management Decision, 50(3), 502–520. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, M. G., Franzoni, C., & Rossi–Lamastra, C. (2015). Internal social capital and the attraction of early contributions in crowdfunding. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(1), 75–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, D. J., Leboeuf, G., & Schwienbacher, A. (2020). Crowdfunding models: Keep-it-all vs. all-or-nothing. Financial Management, 49(2), 331–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L., Ye, Q., Xu, D., Sun, W., & Jiang, G. (2022). A literature review and integrated framework for the determinants of crowdfunding success. Financial Innovation, 8(1), 41. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, H., & Schaefer, D. (2017). Guidelines for successful crowdfunding. Procedia Cirp, 60, 398–403. [Google Scholar]

- Gai, L., Algeri, C., Ielasi, F., & Manganiello, M. (2025). Sustainability-Oriented Equity Crowdfunding: The Role of Proponents, Investors, and Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 17(5), 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunning, R. (1952). The Technique of Clear Writing. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hörisch, J. (2018). ‘Think big’ or ‘small is beautiful’? An empirical analysis of characteristics and determinants of success of sustainable crowdfunding projects. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 10(1), 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hörisch, J., & Tenner, I. (2020). How environmental and social orientations influence the funding success of investment-based crowdfunding: The mediating role of the number of funders and the average funding amount. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 161, 120311. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanović, T. (2019). Crowdfunding: What do we know so far? International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 16(1), 1950009. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M. J., Hall, C. M., & Han, H. (2021). Behavioral influences on crowdfunding SDG initiatives: The importance of personality and subj ective well-being. Sustainability, 13(7), 3796. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, J.-A., & Siering, M. (2015, May 26–29). Crowdfunding success factors: The characteristics of successfully funded projects on crowdfunding platforms. European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS 2015), Münster, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Lagazio, C., & Querci, F. (2018). Exploring the multi-sided nature of crowdfunding campaign success. Journal of Business Research, 90, 318–324. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, P. T., & Law, A. O. (2016). Crowdfunding for renewable and sustainable energy projects: An exploratory case study approach. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 60, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lehner, O. M., & Nicholls, A. (2017). Social finance and crowdfunding for social enterprises: A public–private case study providing legitimacy and leverage. In Crowdfunding and entrepreneurial finance (pp. 113–128). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F. (2008). Annual report readability, current earnings, and earnings persistence. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 45(2–3), 221–247. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., & Chen, Z. (2018). Performance evaluation of machine learning methods for breast cancer prediction. Applied and Computational Mathematics, 7(4), 212–216. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X., Hu, X., & Jiang, J. (2020). Research on the effects of information description on crowdfunding success within a sustainable economy—The perspective of information communication. Sustainability, 12(2), 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, Z. C., Elkan, C., & Naryanaswamy, B. (2014, September 15–19). Optimal thresholding of classifiers to maximize F1 measure. Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases: European Conference, ECML PKDD 2014, Nancy, France. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Zhang, K., Xue, W., & Zhou, Z. (2024). Crowdfunding innovative but risky new ventures: The importance of less ambiguous tone. Financial Innovation, 10(1), 27. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L., Jiang, W., Xu, J., & Wang, F. (2022). The importance of project description to charitable crowdfunding success: The mediating role of forwarding times. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 845198. [Google Scholar]

- Macht, S. (2014). Reaping value-added benefits from crowdfunders: What can we learn from relationship marketing? Strategic Change, 23(7–8), 439–460. [Google Scholar]

- Maehle, N. (2020). Sustainable crowdfunding: Insights from the project perspective. Baltic Journal of Management, 15(2), 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollick, E. (2014). The dynamics of crowdfunding: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moy, N., Chan, H. F., & Torgler, B. (2018). How much is too much? The effects of information quantity on crowdfunding performance. PLoS ONE, 13(3), e0192012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahm, F. S. (2022). Receiver operating characteristic curve: Overview and practical use for clinicians. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology, 75(1), 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndumbaro, F., Mofulu, G., & Daudi, P. N. (2023). Extrinsic Motivation toward Entrepreneurs’ Intention to Adopt Crowdfunding: The Case of Kiva Lending Crowdfunding. African Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship (AJIE), 2(1), 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novaković, J. D., Veljović, A., Ilić, S. S., Papić, Ž., & Tomović, M. (2017). Evaluation of classification models in machine learning. Theory and Applications of Mathematics & Computer Science, 7(1), 39. [Google Scholar]

- Ortas, E., Burritt, R. L., & Moneva, J. M. (2013). Socially Responsible Investment and cleaner production in the Asia Pacific: Does it pay to be good? Journal of Cleaner Production, 52, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhankangas, A., & Renko, M. (2017). Linguistic style and crowdfunding success among social and commercial entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(2), 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzelli, A. M., Natalicchio, A., Panniello, U., & Roma, P. (2019). Understanding the crowdfunding phenomenon and its implications for sustainability. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 141, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, F., & Faria, L. G. (2019). Addressing the SDGs in sustainability reports: The relationship with institutional factors. Journal of Cleaner Production, 215, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S. (2024). Antecedents and consequences of relationship motivation in reward-based crowdfunding. Journal of Alternative Finance, 1(2), 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- Scheaf, D. J., Davis, B. C., Webb, J. W., Coombs, J. E., Borns, J., & Holloway, G. (2018). Signals’ flexibility and interaction with visual cues: Insights from crowdfunding. Journal of Business Venturing, 33(6), 720–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheinbaum, A. C., Hampel, S., & Kang, M. (2017). Future developments in IMC: Why e-mail with video trumps text-only e-mails for brands. European Journal of Marketing, 51(3), 627–645. [Google Scholar]

- Shneor, R., & Vik, A. A. (2020). Crowdfunding success: A systematic literature review 2010–2017. Baltic Journal of Management, 15(2), 149–182. [Google Scholar]

- Technavio. (2022). Crowdfunding market development, type, and geography—Forecast and analysis 2023–2027. Available online: https://www.technavio.com/report/crowdfunding-market-industry-service-analysis (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Testa, S., Nielsen, K. R., Bogers, M., & Cincotti, S. (2019). The role of crowdfunding in moving towards a sustainable society. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 141, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Tomczak, A., & Brem, A. (2013). A conceptualized investment model of crowdfunding. Venture Capital, 15(4), 335–359. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2015). The 17 sustainable development goals. United Nations. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Vismara, S. (2019). Sustainability in equity crowdfunding. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 141, 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N., Li, Q., Liang, H., Ye, T., & Ge, S. (2018). Understanding the importance of interaction between creators and backers in crowdfunding success. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 27, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F., & Zhang, F. (2018). Crowdfunding under social learning and network externalities. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3115891 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Younkin, P., & Kashkooli, K. (2016). What problems does crowdfunding solve? California Management Review, 58(2), 20–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., & Tian, Y. (2021). Choice of pricing and marketing strategies in reward-based crowdfunding campaigns. Decision Support Systems, 144, 113520. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M., Lu, B., Fan, W., & Wang, G. A. (2018). Project description and crowdfunding success: An exploratory study. Information Systems Frontiers, 20, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Variables | Measures |

|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | |

| Crowdfunding Success | The value of successful fundraising is 1, otherwise it is 0 |

| Independent Variable | |

| Length | Number of words in project description |

| Readability | The negative value of Gunning Fox Index |

| Control Variable | |

| Goal | The financial amount the projects aim to reach (US dollars) |

| Duration | The number of days that a project accepts funds from backers |

| Year | The year when the projects were launched |

| SDGs Goal | |

|---|---|

| 1. No Poverty | 10. Reduced Inequalities |

| 2. Zero Hunger | 11. Sustainable Cities and Communities |

| 3. Good Health and Well-being | 12. Responsible Consumption and Production |

| 4. Quality Education | 13. Climate Change |

| 5. Gender Equality | 14. Life Below Water |

| 6. Clean Water and Sanitation | 15. Life on Land |

| 7. Affordable and Clean Energy | 16. Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions |

| 8. Decent Work and Economic Growth | 17. Partnerships for the Goals |

| 9. Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure | |

| Variable | Min | 1st Q | Medium | Mean | 3rd Q | Max | Std Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| length | 105 | 276 | 508 | 676.16 | 902 | 4921 | 558.11 |

| readability | −155.82 | −15.4 | −13.49 | −11.87 | −11.31 | −5.36 | 4.31 |

| goal | 1 | 5000 | 18,000 | 85,066.1 | 50,000 | 100,000,000 | 1,247,912 |

| duration | 1 | 30 | 30 | 34.78 | 40 | 60 | 11.07 |

| year | 2009 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014.66 | 2016 | 2017 | 1.23 |

| SDGs_kw_count | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2.75 | 4 | 40 | 3.26 |

| average_basket_value | 0 | 13 | 49.81 | 103.49 | 115.41 | 4408.68 | 197.43 |

| Status of Projects | Count of Projects | Average of the Amount of Goal | Sum of Backers | Sum of the Amount of Pledged | Average Basket Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fail | 8754 (69.4%) | 110,468.78 | 228,089 | 27,484,671.63 | 76.55 |

| Success | 3859 (30.6%) | 27,441.03 | 2,857,294 | 345,281,520.2 | 164.62 |

| Total | 12,613 | 85,066.10 | 3,085,383 | 372,766,191.8 | 103.49 |

| Status of Projects | Average of Length | Average of Readability | Average of SDGs_kw_count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fail | 588.05 | −14.20 | 2.51 |

| Success | 876.06 | −13.60 | 3.32 |

| Total | 676.17 | −14.01 | 2.76 |

| Sustainable Orientation | Count of Projects | Average of the Amount Goal | Average of Backers | Sum of the Amount Pledged | Average Basket Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | 2853 (22.6%) | 104,401.64 | 100.90 | 24,378,654.51 | 59.99 |

| Yes | 9760 (77.4%) | 79,414.02 | 286.63 | 3,483,875,373.3 | 116.21 |

| Total | 12,613 | 85,066.10 | 244.62 | 3,727,661,918.8 | 103.49 |

| Sustainable Orientation | Average of Length | Average of Readability |

|---|---|---|

| No | 342.12 | −13.56 |

| Yes | 773.82 | −14.15 |

| Total | 676.17 | −14.01 |

| SDGs Goal | Number of Projects Related |

|---|---|

| 1. No Poverty | 2533 |

| 2. Zero Hunger | 2532 |

| 3. Good Health and Well-being | 2794 |

| 4. Quality Education | 1824 |

| 5. Gender Equality | 1043 |

| 6. Clean Water and Sanitation | 349 |

| 7. Affordable and Clean Energy | 3815 |

| 8. Decent Work and Economic Growth | 810 |

| 9. Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure | 1083 |

| 10. Reduced Inequalities | 1383 |

| 11. Sustainable Cities and Communities | 1370 |

| 12. Responsible Consumption and Production | 3949 |

| 13. Climate Change | 1092 |

| 14. Life Below Water | 1087 |

| 15. Life on Land | 1859 |

| 16. Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions | 1306 |

| 17. Partnerships for the Goals | 21 |

| SDGs Keywords Ranking | Number of SDGs Keywords | Count of Projects |

|---|---|---|

| A | ≥ 20 | 47 (0.37%) |

| B | 6−19 | 1728 (13.7%) |

| C | 3−5 | 3250 (25.7%) |

| D | 1−2 | 4735 (37.5%) |

| E | 0 | 2853 (22.6%) |

| Total | 12,613 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls Only | Words_Count | Reada-Bility | SDGs_kw_Count | Average_Basket_Value | Length, Reada-Bility | Length, Readability, SDGs_kw_Count | All Variables | |

| Controls | ||||||||

| log(Goal) | −0.2936 *** | −0.4592 *** | −0.2894 *** | −0.3645 *** | −0.4153 *** | −0.4549 *** | −0.4606 *** | −0.5613 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Duration | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Main effects | ||||||||

| log(length) | 1.1260 *** | 1.1329 *** | 1.0729 *** | 1.0080 *** | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| Readability | 0.0337 *** | 0.0446 *** | 0.0487 *** | 0.0512 *** | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| log(SDGs_kw_count) | 0.5569 *** | 0.1110 *** | 0.0945 *** | |||||

| (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.004) | ||||||

| average_basket_value | 0.0041 *** | 0.0034 *** | ||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||||

| constant | 1.4699 *** | −3.8900 *** | 1.9094 *** | 1.7417 *** | 2.1824 *** | −3.3420 *** | −2.9416 *** | −1.9368 *** |

| Model Summary | ||||||||

| Pseudo R-square | 0.05492 | 0.1468 | 0.05718 | 0.08351 | 0.1151 | 0.1496 | 0.1504 | 0.1911 |

| Model 1 Mainstream Model | Model 8 Proposed Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 70.60% | 75.90% |

| F-measure | 17.41% | 49.58% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yin, L.-Y.; Khalil, F.C.; Khalil, L.J.; Kaspard, J.A. The Role of Project Description in the Success of Sustainable Crowdfunding Projects. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040200

Yin L-Y, Khalil FC, Khalil LJ, Kaspard JA. The Role of Project Description in the Success of Sustainable Crowdfunding Projects. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(4):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040200

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Li-Yun, Fleur C. Khalil, Lionel J. Khalil, and Jeanne A. Kaspard. 2025. "The Role of Project Description in the Success of Sustainable Crowdfunding Projects" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 4: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040200

APA StyleYin, L.-Y., Khalil, F. C., Khalil, L. J., & Kaspard, J. A. (2025). The Role of Project Description in the Success of Sustainable Crowdfunding Projects. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(4), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040200