Abstract

Pneumomediastinum (PM) implies an abnormal condition where a collection of free air or gas is entrapped within the fascial planes of mediastinal cavity. It is considered as benign entity, but an uncommonly seen complication of craniofacial injuries. We report a case of a 63-year-old male patient with the presenting sign of closed rhinolalia who was diagnosed with retropharyngeal emphysema and PM due to a linear and nondisplaced fracture of midface. The patient cited multiple efforts of intense nasal blowing shortly after a facial injury by virtue of a motorcycle accident. He was admitted in our clinic for closer observation and further treatment. The use of a face mask for continuous positive airway pressure was temporarily interrupted, and high concentrations of oxygen were delivered via non-rebreather mask. Patient’s course was uncomplicated and he was discharged few days later, with almost complete resolution of cervicofacial emphysema and absence of residual PM in follow-up imaging tests. Closed rhinolalia (or any acute alteration of voice) in maxillofacial trauma patients should be recognized, assessed, and considered within the algorithm for PM and retropharyngeal emphysema diagnosis and management. For every single case of cervicofacial emphysema secondary to facial injury, clinicians should maintain suspicion for retropharyngeal emphysema or PM development.

The term pneumomediastinum (PM) implies an abnormal condition, where a free collection of air or gas is identified within the fascial planes of the mediastinal cavity. In 1819, the first report about PM was documented by Laennec.[1] The occurrence of PM has been attributed to several etiologies; however, it is not commonly seen as a complication of craniofacial injuries.[2,3] We reported a case of a patient presented with sign of closed rhinolalia and diagnosed with massive cervicofacial emphysema and PM, as a consequence of a linear and nondisplaced fracture of midface.

Case Report

A 63-year-old male patient presented to emergency department (ED) because of a motorcycle accident, occurred 1 h and 20 min ago. He chiefly complained for ecchymosis, pain, and edema of right periorbital area, resulting in inability to open his right eye, as well as marked alteration of his voice. The patient cited multiple efforts of intense nasal blowing, before his admission to ED, within the first 40 min after the injury. His medical history was remarkable for moderate and well-controlled hypertension and sleep obstructive apnea treated with a device of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).

His vital signs were recorded within normal limits and he remained coherent, alert, and fully oriented, with normal neurological status. He was eupneic and hemodynamically stable, with absence of chest pain or respiratory distress, while his pupils were found equal and reactive to both light and accommodation, without abnormalities of vision and ocular motility. On physical examination, crepitation was evident after tactile palpation of right periorbital area, both cheeks, anterior and lateral neck surfaces, and left anterior thoracic wall. Also, he confirmed mild hypesthesia along the distribution of right infraorbital nerve and discharge of few bloody drops from unilateral nostril shortly after the injury. Mobile or displaced fragments of facial skeleton were not detected. Intranasal examination did not reveal traumatic septal deviation, mucosal swelling (congestion), bloody nasal discharge, or hematoma formation. The pitch of his voice was increased, characterized by hyponasality, as typically occurred in closed rhinolalia. On auscultation, Hamman’s sign (i.e., crunching or rasping sound heard over the left precordium simultaneously with systole or exhalation)[4] was not detected.

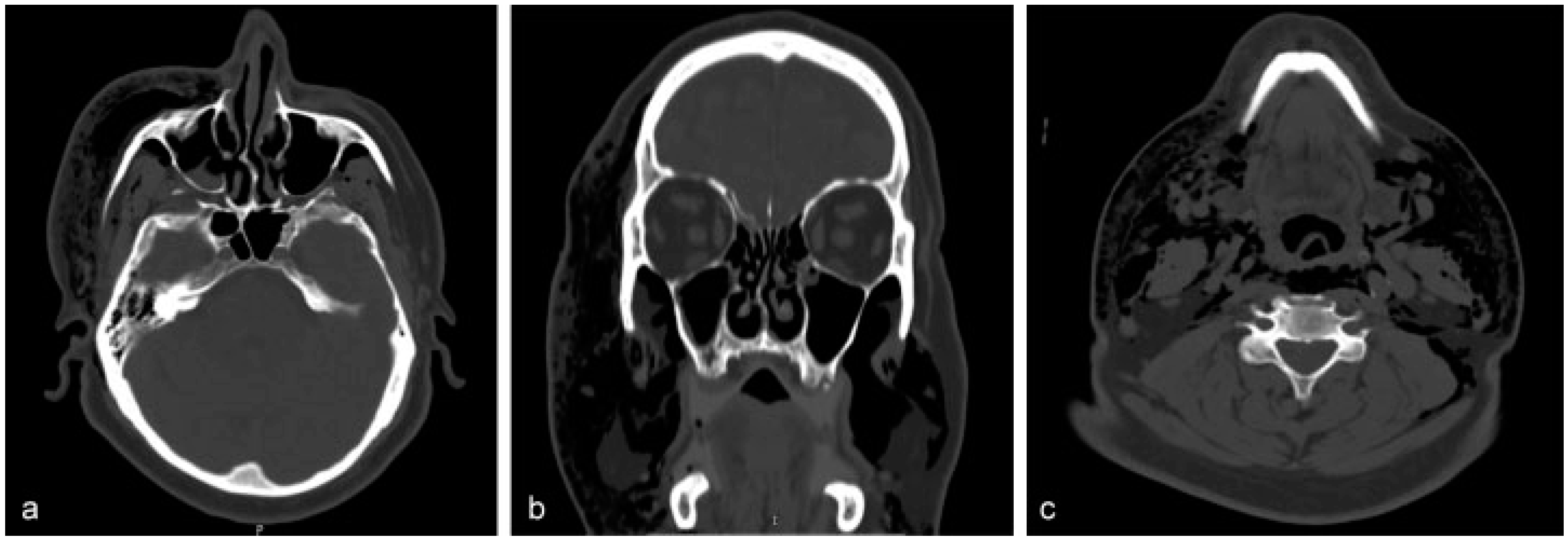

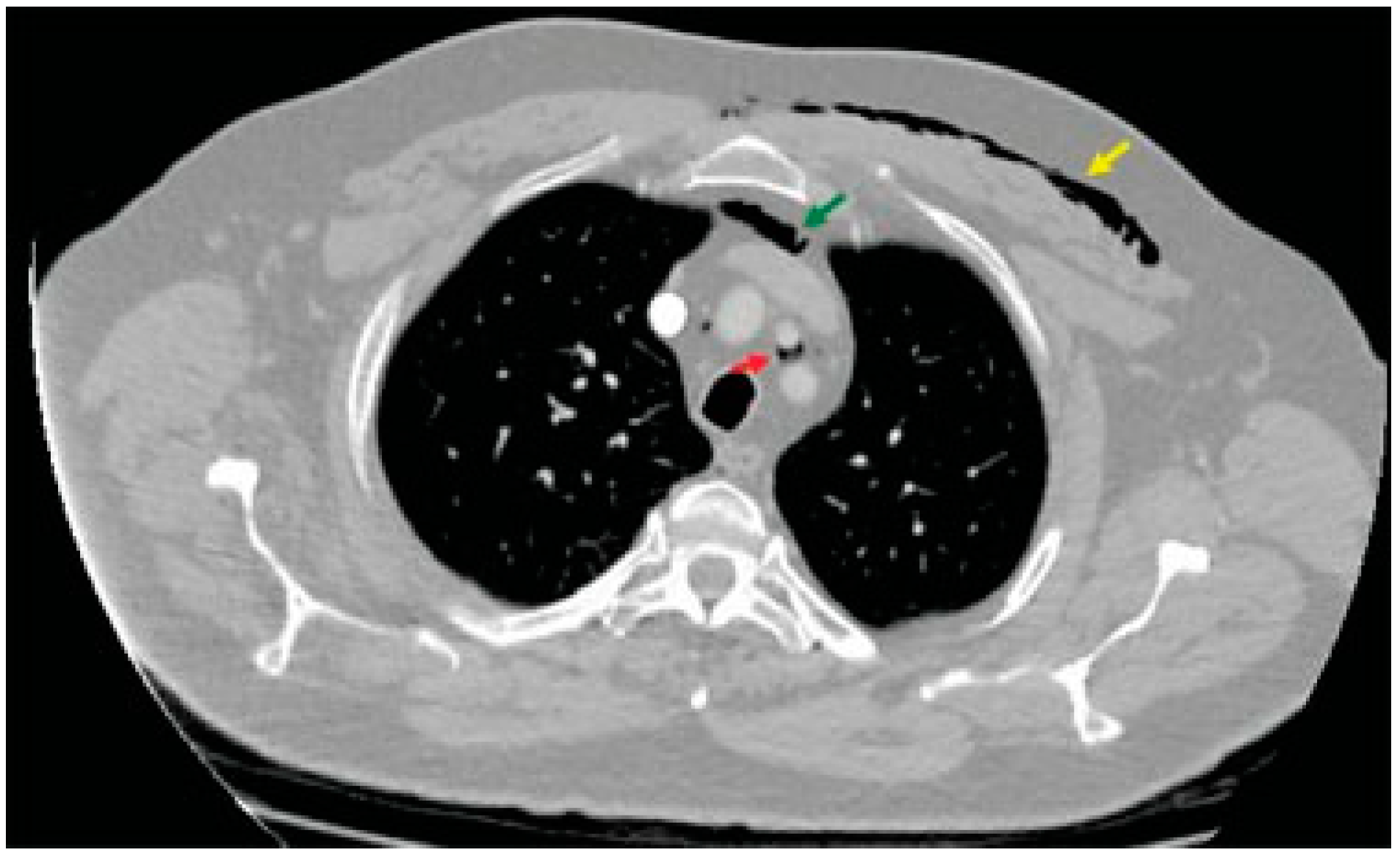

Routine blood tests, arterial blood gases, electrocardiography, and cardiac enzymes did not reveal any discrepancy. The anteroposterior and lateral views of plain radiographs of the neck showed scattered and lucent streaks owing to the presence of free air (Figure 1). Full-body computed tomo-graphic (CT) scan documented a nondisplaced fracture of right anterior sinus wall extending to the base of frontal process of ipsilateral maxillary bone (Figure 2a). Besides, it demonstrated pneumo-orbitus and massive emphysema that either occupied or extended to the following spaces: right temporal, bilateral buccal, bilateral parapharyngeal, bilateral carotid, retropharyngeal, prevertebral, visceral, anterior neck, and right posterior cervical (Figure 2b,c). The air had also spread to subcutaneous tissue of the left anterior chest wall and to the superior mediastinum, both retrosternally and between left common carotid and subclavian artery (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Neither thoracic CT nor chest plain radiographs evidenced signs of rib or clavicle fracture.

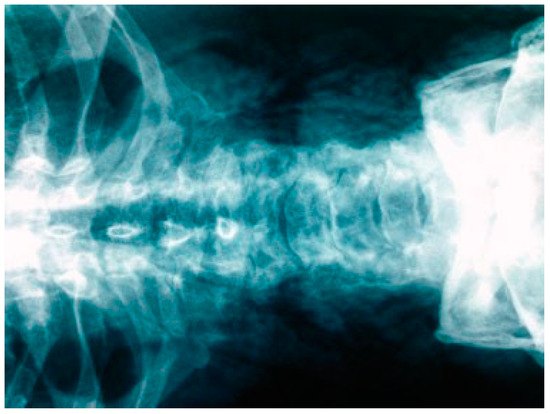

Figure 1.

Scattered and lucent streaks owing to the presence of free air in the patient’s neck.

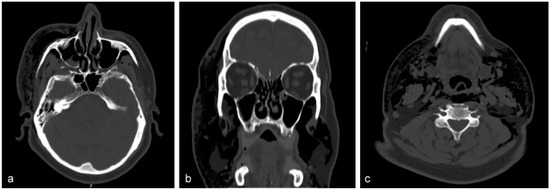

Figure 2.

(a) The source of air leakage: the anterior maxillary wall. (b,c) The extensions of the air to various sites and spaces of cervicofacial region.

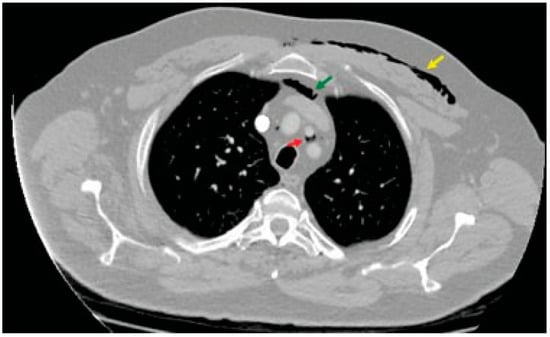

Figure 3.

The air collections within the subcutaneous tissue of the left anterior chest wall (yellow arrow), behind the sternum (green arrow), and between the left common carotid and subclavian artery (red arrow) in transverse view.

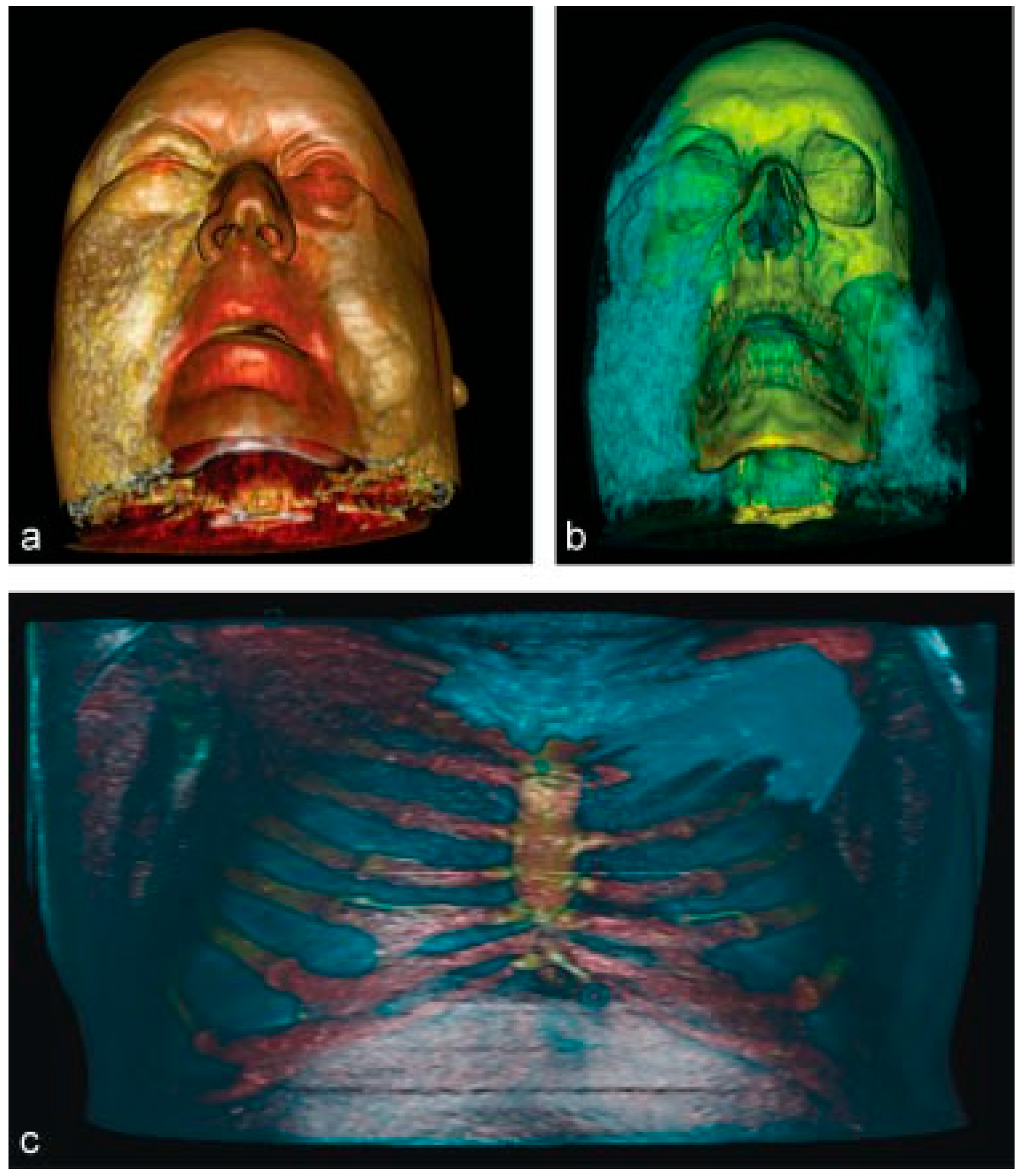

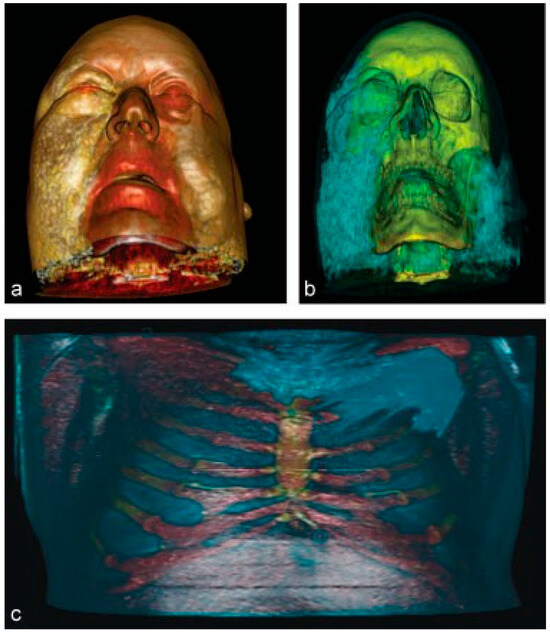

Figure 4.

(a–c) Depiction of the air collections of both maxillofacial and thoracic regions after 3D reconstruction.

The patient remained stable and underwent endoscopic visualization of naso- and oropharynx, upper esophagus, larynx, and tracheawhich did not reveal other possible sources of air leakage other than the fracture. Except from a few superficial facial abrasions and a mild injury of left radiocarpal joint, other traumatic lesions were not identified.

The patient was admitted in our clinic for closer observation and further treatment. Due to the fact that the fracture was linear and undisplaced, without associated esthetic and/or functional complications, the treatment was conservative and included administration of high concentrations of oxygen (up to ~100%) at a mean rate of 6 to 10 L/min via non-rebreather mask (low-flow delivery of oxygen), bed rest, prophylactic antibiotics (amoxicillin + metronidazole), nasal decongestants, corticosteroids, and analgesics. For prevention of increased air pressure inside the maxillary sinus, he was also instructed to avoid blowing his nose, to keep his mouth open in case of sneeze or cough, and to not use a CPAP facial mask for at least the next week. Patient’s course was uncomplicated and the pitch of his voice returned to its previous status within the first 2 days. He was discharged after completion of a 5-day intrahospital stay, with almost complete resolution of cervicofacial emphysema and absence of residual PM in follow-up radiographic examinations.

Discussion

The formation of PM is considered either spontaneous (named Hamman’s or Macklin’s syndrome when combined with subcutaneous emphysema[5]) or secondary, because of an extraor intrathoracic cause of air/gas escape.[6] Currently, PM secondary to facial injuries is not commonly seen and its description in literature is limited to case reports.[2,3] The etiopathological mechanism of PM in the context of cranio-maxillofacial trauma presupposes escape of high-pressured air through mucoperiostal tears created by the fractures of bones forming the paranasal sinuses. Provocative factors may be Valsalva maneuver, cocaine ingestion, barotrauma, traumatic exposure to high-pressure air device, and vigorous nose blowing, sneeze, or cough.[7,8] Significant amounts of air/gas leak from the fracture line and progressively migrate to the mediastinal cavity, by following the route of least resistance. Providing that the latter is defined by the neck fascial spaces, the air follows the anatomical communications of parapharyngeal space with the carotid sheath and retropharyngeal space.[9] Thereby, the air passing through these spaces can reach to the mediastinum.

Every patient who presents with craniomaxillofacial trauma (particularly paranasal and ethmoid-orbital fractures) and mentions forceful, drawn-out, or repeated efforts of nasal blowing is high-risk candidate for the development of a wide-spread cervicofacial emphysema and PM. Such patients exhibit crepitation signs when applying tactile palpation of both cervicofacial region and anterior thoracic surface. Chest pain, persistent cough, sore throat, dysphagia, and shortness of breath are the most frequent symptoms in case of PM.[10]

On the other hand, rhinolalia or any sudden alteration of voice in patients with midfacial trauma may be a sign suggesting dissection of air through the retropharyngeal space and, therefore, possible spread to the mediastinal cavity.[11,12] Closed rhinolalia or “rhinolalia clausa” is characterized by hyponasality, which implies reduction or absence of normal resonance of nasal consonants “m,” “n,” and “ng,” and their nearby vowels.[13] This finding indicates various causes of obstruction in nasal cavity or nasopharynx (e.g., tumors, nasal polyps, adenoid hypertrophy). However, if the obstruction specifically affects the posterior parts of the nasal cavity or nasopharynx, closed rhinolalia (posterior) is presented with the nasal “m,” “n,” “ng” to be heard as their plosives “b,” “d,” and “g,” respectively [14].

To date, the literature contains case reports or case series of single-center experiences that have documented the association between the uncommon entity of primary/spontaneous PM and rhinolalia, sore throat, hoarseness, or voice alteration.[15,16,17,18] Nevertheless, Hoover et al. [19] stressed that rhinolalia may be underestimated by thoracic surgeons. In fact, closed rhinolalia sometimes presents similarly to a common cold or “stuffy nose” and can unintentionally be missed.[20]

Closed rhinolalia is described as the presenting sign of nonspontaneous/secondary PM or retropharyngeal emphysema only in scarce case reports; its presentation has been sporadically emphasized when PM arose due to maxillary sinus fracture,[21] radical neck dissection,[22] general anesthesia,[22] tonsillectomy,[11] odontoid process fracture,[23] chest trauma with pneumothorax,[12] penetrating neck injury,[24] and bronchiolitis obliterans in the setup of graft versus host disease [25].

Between September 1, 2013, and September 31, 2017, in ED, we managed a total of 3514 patients with various types of oromaxillofacial injuries. Among them, 13 cases (0.37%) were clinically diagnosed with evident facial emphysema (puffy facial swelling, crepitation on palpation). The assessment with CT scan revealed extension to the mediastinum in three (0.09%) out of the total patients, while closed rhinolalia was only apparent in the presented case.

Whenever the diagnosis of PM is clinically suspected, patients should be carefully monitored and undergo a series of imaging (head, neck, and thorax CT), laboratory (blood tests, electrocardiograph), and endoscopic (integrity of upper aerodigestive tract) examinations that are essential to contribute to meticulous differential diagnosis.[9,26] There is no need for routine use of esophagography,[27,28] unless the mechanism of injury requires investigation of possible esophageal tear. Elevated white cell count, abdominal tenderness, pleural effusion, and air collection within the pericardium or upper abdominal cavity, encircling the distal esophagus, may signalize perforation of esophagus.[28] While the entrapped air is slowly absorbed by surrounding tissues within 2 to 14 days,[29] the administration of high concentrations of oxygen accomplishes faster PM resolution by fostering the process of nitrogen washout. Inhalation of nitrous oxide during general anesthesia should be avoided.[30] The same applies for the high-flow oxygen delivery systems;[29] in case of acute maxillofacial trauma or maxillofacial surgery, patients treated by CPAP should withhold its use for a few days.[31] Chebel et al.[32] reported a case where oxygen delivery with CPAP via a face mask resulted in subcutaneous emphysema, PM, and bilateral pneumothoraces shortly after the end of an orthognathic surgery. In our case, the temporary interruption of CPAP use lasted for 8 days to secure soft callus formation in fracture line. The measure of manual “milking” of the entrapped air toward an exit point (tracheostomy, laceration, or paranasal cavity) is recommended without harmful consequences [33]

PM might lead to life-threatening complications such as pneumothorax, pneumopericardium, cardiac tamponade, and mediastinitis.[34] Additionally, a retropharyngeal emphysema may impede airway patency.[35] Severe dyspnea; dysphagia; difficulty in speech; retrosternal chest pain irradiating to the arms, neck, and back; cyanosis; distended nonpulsatile jugular veins; tachycardia; hypotension; and collapse are life-threatening manifestations that require timely recognition and emergent intervention.[9] Mediastinal emphysema provoked by isolated midfacial fractures together with aspiration of blood led to a patient’s death, according to Gouda et al. [36].

Conclusion

Management of PM may be a field of interest for many several specialties, depending on both its preceding factor and the involved anatomical sites. Closed rhinolalia (or any alteration of voice) in craniomaxillofacial trauma patients should be recognized, properly assessed, and considered within the algorithm of diagnosis and management for either PM or massive cervicofacial emphysema. In every single case of facial emphysema, clinicians should take into consideration all the associated signs which carry a high level of suspicion for extension to the mediastinal cavity or retropharyngeal space. PM is generally a “benign” entity and the prognosis of that induced by maxillofacial injuries should be expected to be very good after the appropriate management.

Note

There was patient’s consent for this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Minton, G.; Tu, H.K. Pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and cervical emphysema following mandibular fractures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1984, 57, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demers, G.; Camp, J.L.; Bennett, D. Pneumomediastinum caused by isolated oral-facial trauma. Am J Emerg Med 2011, 29, 841.e3–841.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procacci, P.; Zanette, G.; Nocini, P.F. Blunt maxillary fracture and cheek bite: Two rare causes of traumatic pneumomediastinum. Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016, 20, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.H.; Sahn, S.A. Hamman’s sign revisited. Pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum? Chest 1992, 102, 1281–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickley, J. Hamman syndrome. Br J Hosp Med 2016, 77, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caceres, M.; Ali, S.Z.; Braud, R.; Weiman, D.; Garrett, H.E., Jr. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: A comparative study and review of the literature. Ann Thorac Surg 2008, 86, 962–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bejvan, S.M.; Godwin, J.D. Pneumomediastinum: Old signs and new signs. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996, 166, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, F.; Çiftçi, O.; Özlem, M.; Komut, E.; Altunbilek, E. Subcutaneous emphysema, pneumo-orbita and pneumomediastinum following a facial trauma caused by a high-pressure car washer. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2014, 20, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loretan, S.; Scolozzi, P. Pneumomediastinum secondary to isolated orbital floor fracture. J Craniofac Surg 2011, 22, 1502–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koullias, G.J.; Korkolis, D.P.; Wang, X.J.; Hammond, G.L. Current assessment and management of spontaneous pneumomediastinum: Experience in 24 adult patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2004, 25, 852–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braverman, I.; Rosenmann, E.; Elidan, J. Closed rhinolalia as a symptom of pneumomediastinum after tonsillectomy: A case report and literature review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997, 116, 551–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braverman, I.; Vromen, A.; Shapira, M.Y.; Freund, H.R. Hyponasality caused by retronasopharyngeal air as a symptom of pneumomediastinum. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998, 118, 903–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalston, R.M.; Warren, D.W.; Dalston, E.T. The identification of nasal obstruction through clinical judgments of hyponasality and nasometric assessment of speech acoustics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1991, 100, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.; McMahon, S.D. Disorders of speech. In Scott-Brown’s Otolaryngology, 7th ed.; Gleeson, M., Clarke, R.W., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gerazounis, M.; Athanassiadi, K.; Kalantzi, N.; Moustardas, M. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: A rare benign entity. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003, 126, 774–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunluoglu, M.Z.; Cansever, L.; Demir, A.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009, 57, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahid, B.; Bosanac, A. Acute substernal chest pain and rhinolalia in an 18-year-old woman. Postgrad Med 2008, 120, 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.W.; Chiu, W.Y.; Lo, Y.H. Sore throat may be a clue to the early diagnosis of spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Am J Emerg Med 2015, 33, 305.e5–305.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, L.R.; Febinger, D.L.; Tripp, H.F. Rhinolalia: An underappreciated sign of pneumomediastinum. Ann Thorac Surg 2000, 69, 615–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braverman, I.; Marom, N.; Greenberg, E. Rhinolalia as a symptom of pneumomediastinum after radical neck dissection. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000, 122, 925–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Petteruti, F.; Tanga, M.; Luciano, A.; Lerro, A. Pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema unusual complications of blunt facial trauma. Indian J Surg 2011, 73, 380–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chang, Y.Y.; Yien, H.W.; Hseu, S.S.; Chan, K.H.; Tsai, S.K. Subcutaneous emphysema associated with pneumomediastinum after general anesthesia–closed rhinolalia as an initial presentation in one of two cases. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan 2005, 43, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hilton, J.M.; Tassone, P.; Hanif, J.; Blagnys, B. Anterior fracture dislocation of the odontoid peg inankylosing spondylitis as a causefor rhinolalia clausa: A case study. J Laryngol Otol 2008, 122, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braverman, I.; Avior, G.; Malatskey, S. Pneumomediastinum owing to a neck stab wound presenting as rhinolalia. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008, 37, E87–E89. [Google Scholar]

- Bitan, M.; Resnick, I.B.; Or, R.; et al. Rhinolalia as a presenting sign of pneumomediastinum complicating post peripheral blood stem cell transplantation bronchiolitis obliterans. Am J Hematol 2003, 74, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, B.; Hunt, P. Pneumomediastinum secondary to facial trauma. Am J Emerg Med 2017, 35, 192.e3–192.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newcomb, A.E.; Clarke, C.P. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: Abenign curiosity or a significant problem? Chest 2005, 128, 3298–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhos, C.T.; Pupovac, S.S.; Ata, A.; Fantauzzi, J.P.; Fabian, T. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: An extensive workup is not required. J Am Coll Surg 2014, 219, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrides, H.; Lawton, L.D. Don’t blow it! Extensive subcutaneous emphysema of the neck caused by isolated facial injuries: A case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med 2017, 52, e57–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C.H.; Hills, E.C. Traumatic emphysema of the head, neck, and mediastinum associated with maxillofacial trauma: Case report and review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1989, 47, 876–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, N.R.; Fine, M.D.; McRae, R.G.; Millman, R.P. Unusual complication of nasal CPAP: Subcutaneous emphysema following facial trauma. Sleep 1997, 20, 895–897. [Google Scholar]

- Chebel, N.A.; Ziade, D.; Achkouty, R. Bilateral pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum after treatment with continuous positive airway pressure after orthognathic surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010, 48, e14–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparini, J.R.; Ferreira, L.C.; Rangel, V.H. Subcutaneous emphysema induced by supplementary oxygen delivery nasopharyngeal cannula. Case report. Rev Bras Anestesiol 2010, 60, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Santos, S.E.; Sawazaki, R.; Asprino, L.; de Moraes, M.; Fernandes Moreira, R.W. A rare case of mediastinal and cervical emphysema secondary mandibular angle fracture: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011, 69, 2626–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Chen, T.J.; Wu, Y.H.; Tsai, K.C.; Yuan, A. Spontaneous retropharyngeal emphysema and pneumomediastinum presented with signs of acute upper airway obstruction. Am J Emerg Med 2005, 23, 402–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouda, H.S.; Shashidhar; Mestri, C. Mediastinal emphysema due to an isolated facial trauma: A case report. Med Sci Law 2008, 48, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the author. The Author(s) 2018.