Abstract

Epignathus is a rare congenital oropharyngeal teratoma that arises from the oropharynx, especially the sphenoid, palatine, and ethmoid bones. Teratomas are benign tumors containing cells from ectodermal, mesodermal, and endodermal layers. The incidence of epignathus is between 1:35,000 and 1:200,000 live births with a female predominance. We reported an uncommon case of epignathus in a female newborn baby with an ill-defined oral mass protruding through a cleft in the hard palate. Computed tomography scan showed a contrast-enhanced solid mass with areas of calcification simulating a unique case of maxilla duplication. Surgery was performed, the mass was excised successfully, and microscopic analysis confirmed the diagnosis of mature teratoma. The patient evolved with good general health and showed no clinical signs of recurrence. Although epignathus is a rare condition, it should be diagnosed in the fetus as early as possible, especially to avoid fatal airway obstruction. In such cases, the treatment option is exclusively surgical, and complete resection is curative in most cases during the early neonatal period.

Teratomas are congenital germ cell tumors that are composed of multiple tissues of ectodermal, mesodermal, and endodermal origin. It is a benign tumor, although malignancy has been described in adults. Ten percent of teratomas are found in the head and neck area.[1]

Oropharyngeal teratoma originates from the skull base craniofacial structures, particularly the sphenoid, palatine, and ethmoid bones.[2,3] Histologically, it can be classified into four types:[1] dermoid (mesodermal and ectodermal derivatives),[2] teratoid (three germ layer derivatives),[3] true teratoma (three germ layer derivatives, intermediate differentiation), and[4] epignathus, in which the germ cell elements are highly differentiated and has fetal structures.[4] Epignathus is extremely rare and its incidence varies between 1:35,000 and 1:200,000 live births with a female predominance (3:1).[5] The recognition of its etiology is still uncertain; however, several cases of epignathus have been linked to chromosomal abnormalities such as trisomy 13, ring X-chromosome, mosaicism with inactive ring X-chromosome, gonosomal pentasomy 49, gene mutations, or abnormalities in early embryonic development.[6]

Epignathus is usually associated with other malformations and the most common are midline craniofacial clefts, especially the cleft palate.[4] The pathogenesis between oral teratomas and midline malformations remains unclear. Morlino et al[2] introduced the term “craniofacial teratoma syndrome” to define this phenotype as a recognizable developmental field defect of the cephalic pole. This entity comes accompanied by several degrees of craniofacial duplication, which can be subdivided into four general types:[1] single mouth with duplication of the maxillary arch,[2] supernumerary mouth laterally placed with rudimentary segments,[3] single mouth with replication of the mandibular segments,[4] and true facial duplication.[2]

This tumor may be small, interfering only with feeding, or may reach a large size, causing obstruction of the upper airways and consequent death of the newborn.[7] Thus, early diagnosis is imperative, especially in the neonatal period, which facilitates establishing an early treatment plan to prevent serious and sometimes fatal co-complications.[6]

In this study, we present a rare case of congenital epignathus arising from the hard palate with concomitant duplication of the mandible in a newborn girl with a successful outcome.

Case Report

A female neonate was delivered through lower segment caesarian section by a 17-year-old healthy primigravid Brazilian mother at 40 weeks of gestation. Family and early gestational history were unremarkable. There was no reported exposure to teratogenic agents. Serologic tests for cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, and rubella gave normal results. Ultrasound scan, performed at 34 weeks of gestation, showed a fetus with a 3.2 × 2.4 cm anechoic mass with no Doppler signal, thought to originate from the oral cavity. Apgar score of the newborn at the first and fifth minutes of birth was 8 and the weight, along with a pedunculated mass from the palate, was 2.95 kg. Nasotracheal intubation by bronchoscopy was necessary to prevent respiratory distress.

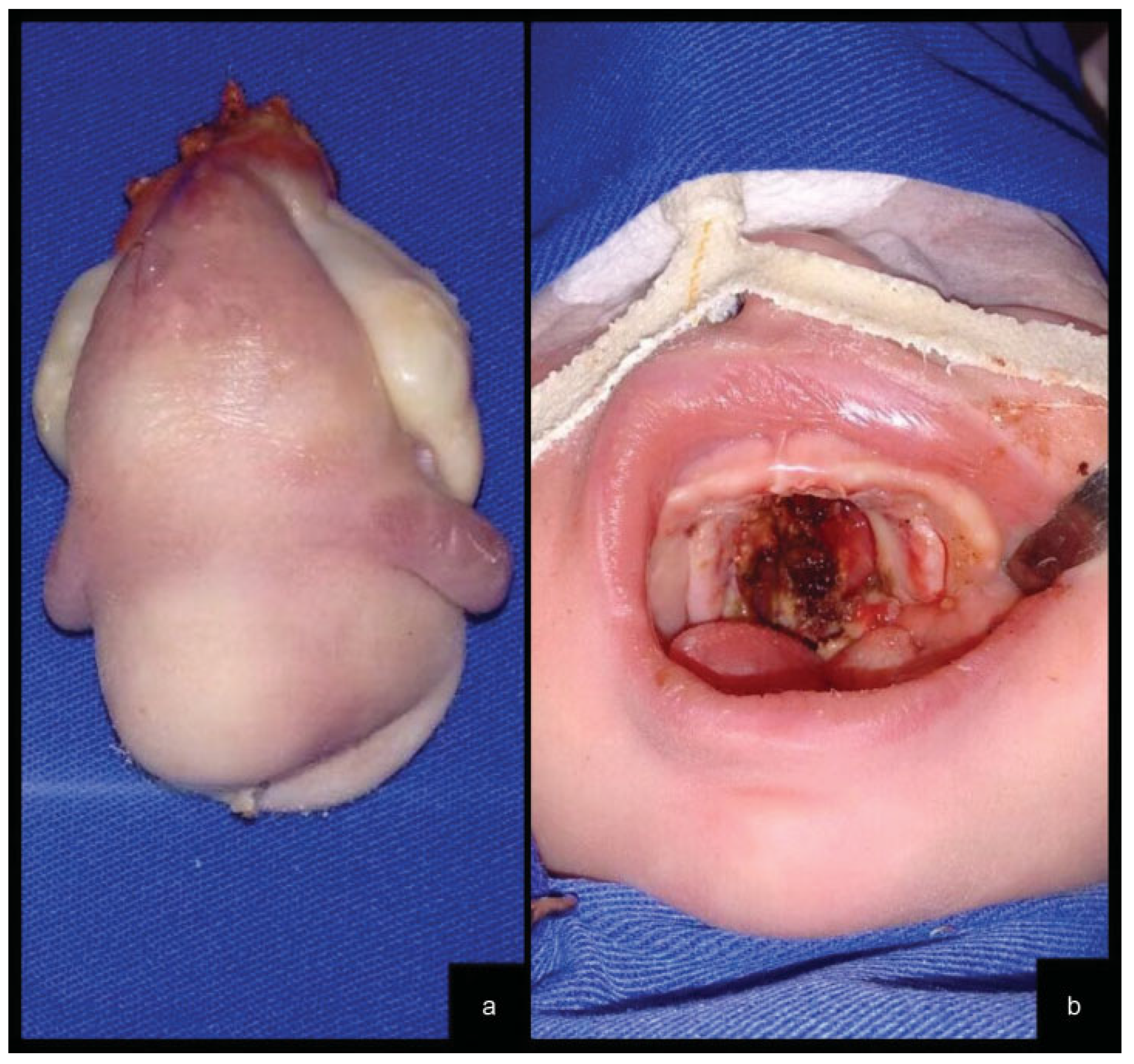

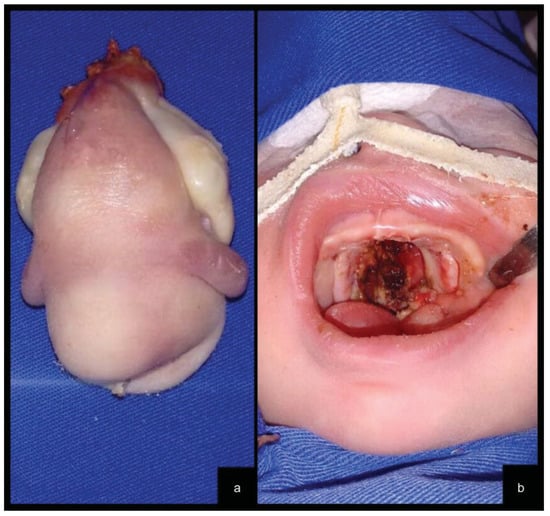

Physical examination performed by the craniofacial surgery team observed the presence of a large oral tumor protruding from the palate that was obliterating the oral cavity. It was a fibroelastic mass with a solid center and contained two lateral ill-defined rubbery nodules. The surface of the growth showed some areas resembling skin and mucosa (Figure 1a) The lips, nose, and tongue were not involved. The newborn also had another solid 1.0-cm mass originating from the lingual aspect of the body of the left mandible (Figure 1b). Computed tomography scan (CT) demonstrated a contrast-enhanced solid mass with areas of calcification and unerupted teeth originated from a hard palate defect and simulating a case of maxilla duplication. CT also showed a V-shape lower jaw with a rudimentary bone strut emerging from the left mandible (Figure 1c–d). Chromosomal analysis of the patient revealed a normal female karyotype.

Figure 1.

Epignathus clinical view. (a) Frontal view of maxilla duplication. (b) Solid mass originating from the lingual aspect of the body of the left mandible. Computed tomographies of the patient’s skull with three-dimensional reconstruction. (c) Frontal view showing maxilla duplication originated from the hard palate and whose bone structure maintains anatomical characteristics very similar to a well-formed jaw. (d) Lateral view showing a tooth-compatible structure arising from maxilla duplication and a V-shape lower jaw with a rudimentary bone strut emerging from the left mandible.

The tumor was successfully completely excised under general anesthesia at the fifth day of life (Figure 2a). Complete excision of both tumors ended with an incomplete cleft palate, which resulted in excellent healing with granulation tissue (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) The surgical specimen contained two lateral ill-defined rubbery nodules. (b) Palate cleft resulting from tumor resection.

For diagnostic complementation, β-human chorionic gonadotropin and alpha-fetoprotein were evaluated. The concentration of the latter was in the normal range after surgery. The surgical specimen measuring 7.5 × 4.0 × 3.5 cm and fixed in 10% formalin was sent for histopathological analysis. Microscopic analysis confirmed the diagnosis of a mature teratoma, with differentiation of tissues of ectodermal, mesodermal, and endodermal origin. The majority appears to be composed of adipose tissue, with areas of aspect and consistency of cartilage and bone. Within the lesion, a tooth-compatible structure measuring 0.6 cm in diameter was observed. The mandibular specimen showed a structure partially covered by nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium, presenting seromucous salivary gland lobes involved by abundant adipose tissue and, in the center, spongy bone tissue containing hematopoietic marrow. Both resected specimens’ margins were free of tumor. After extubation (48 hours after surgery), the patient presented incoordination and hypotonicity of the tongue. Thus, a tracheostomy and gastrostomy were performed. Gradually, after the 30th postoperative day, the tongue had a more central position on the floor of the mouth.

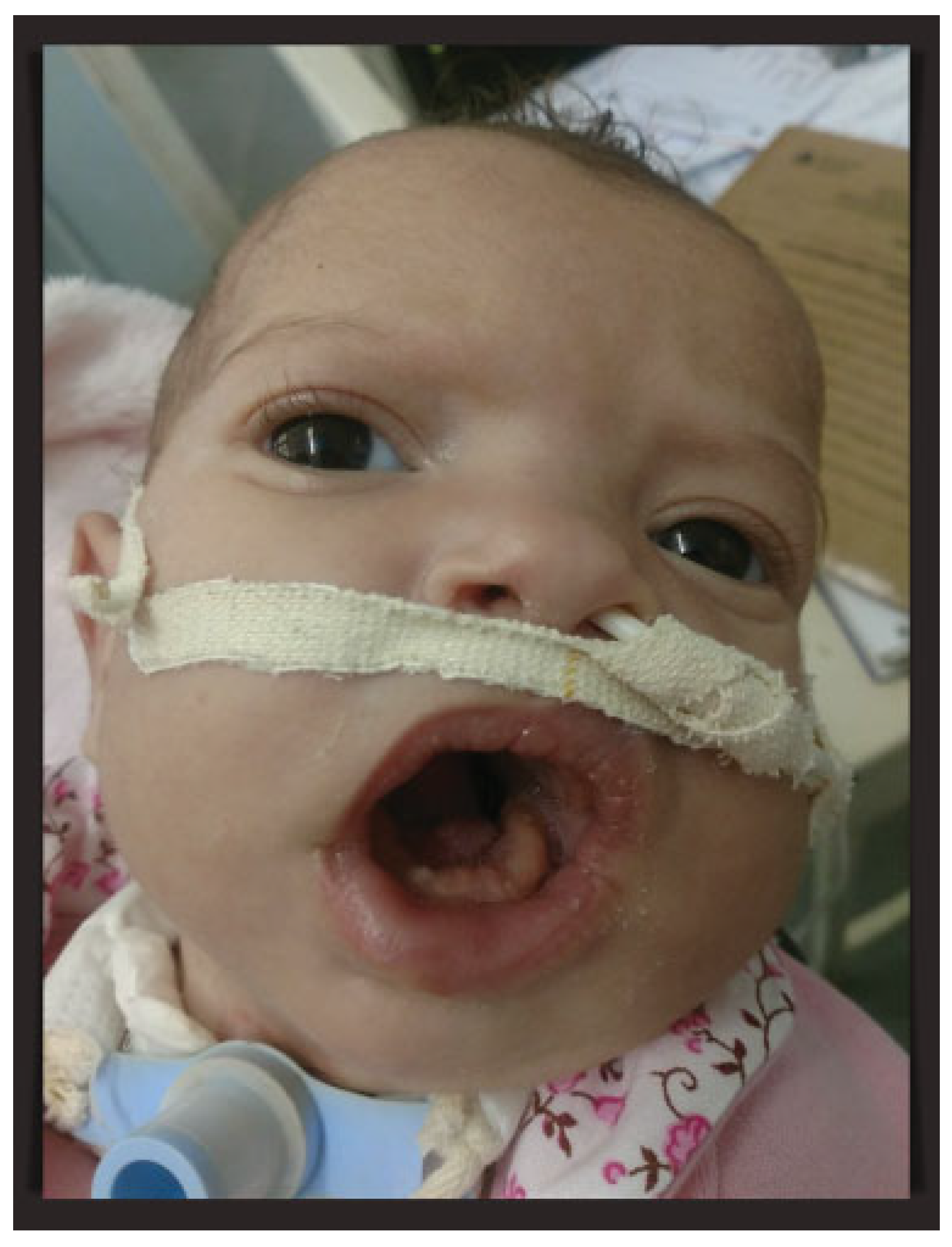

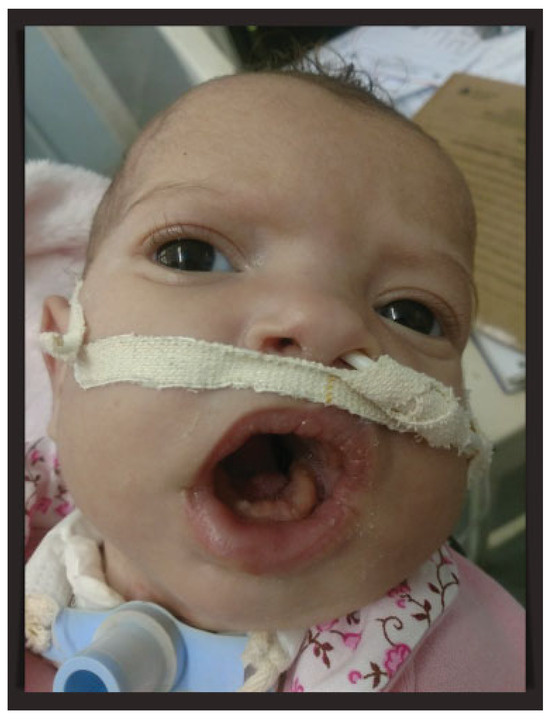

Because of the downward growth of the mandible, the baby maintained an open-mouth posture, which interfered with oral feeding because of the inability to close the mouth and maintaining the sucking movement. Oral exercises had been started in the second postoperative week after complete healing of the oral wounds to encourage sucking movements. At the end of the second month of life, the mouth opening was slightly reduced, but it was decided to keep the patient with tracheostomy until further evaluation. With good weight gain, the neonate was discharged after 60 days of hospitalization. One month later, as a result of cellulitis around the gastrostomy site, the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was removed and the patient was maintained with a nasoenteral tube. After an excellent recovery, the baby at 4 months of age maintains good general health and multidisciplinary follow-up (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Patient at 4 months of age maintaining tracheostomy and nasoenteral tube. Close-up of the baby’s open-mouth posture.

Discussion

Teratomas are monstrous lesions that are composed of tissues foreign to the part in which they arise, and they are exceptionally rare tumors in the head and neck region.[1,2,3] When these tumors are located in the oral cavity and are composed of all layers of germ cells and contain fetal structures or organs, they are called epignathus (which is even rarer). Another pathological variant of epignathus is “fetus-in-fetu” occurring due to the incomplete twinning of monozygotic twins at a primitive stage of the beginning of axial development.[8]

Morlino et al[2] reported 48 cases of teratomas originating at the base of the skull and associated with other cephalic midline anomalies. However, fewcases of epignathus of thehard palate have been described in the literature. Isaacs[9] reported 16 cases and, recently, Ram et al[1] described another unique case of maxillary teratoma. In addition, cases of maxillary duplication do not respect their original anatomical shape, but a disorganized tissue conglomerate with or without teeth included. The present case showed an epignathus originated from the hard palate and whose bone structure maintains anatomical characteristics very similar to a well-formed jaw (Figure 1c, d). Excision of the tumor from the palate resulted in a cleft of the soft palate and the posterior part of the hard palate (Figure 2b). The association of teratoma with midline malformations can be classified within the spectrum of the craniofacial teratoma syndrome.[2]

The etiology of epignathus is still unclear; however, it is speculated that the totipotential embryonic tissues adjacent to the primitive streak and notochord are displaced by some unknown mechanism during ontogenesis.[10] There is no evidence suggesting that epignathus is caused by environmental agents, Mendelian or polygenic inheritance.[11] Sporadic chromosomal changes had been reported, but usually, it has not reported being associated with epignathus.[6,11] Chromosomal analysis of this case revealed a normal female karyotype.

No evidence showed epignathus has genetic predisposition.[11] The probability of having more than one child with epignathus in the same family is very low.[8,11] It is important, therefore, that the parents are antenatally counseled and reassured by the obstetricians regarding absence of risk of bearing another child with epignathus.[8,11,12]

Malignant teratomas are rare and most often found in the sacrococcygeal region.[7] No cellular atypia was observed in the present case. In the absence of an intracranial extension, radical treatment of epignathus teratoma consists of total and early surgical resection of the tumor using the oral approach, as was done in this patient.[4] In cases of tumor recurrence, presence of primitive neural tissue in the tumor, or malignancy, some authors suggest associating radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy after complete tumor resection.[4,7,13] In this situation, monitoring with the dosage of α-fetoprotein may be helpful; otherwise, surgical excision with limited safe margins is suitable for all other benign cases.[4,13,14]

The mortality rate associated with epignathus is high because of obstruction of the airways during delivery or soon thereafter.[8] The prognosis depends on the degree of atypia of the tumor, as well as the presence of deformities and other malformations, such as facial deformities, malocclusion of the jaws and speech and swallowing function.[4] This is a rare condition; however, when the diagnosis is made early, and both the mother and especially the newborn are accompanied by a multidisciplinary team, good results can be achieved.[4,7,15] Orthodontic treatment of the maxillary deformities and the associated cleft palate must be subsequently undertaken.[15] Usually, our team performs the correction of the palate in a single stage by the Veau–Wardill– Kilner technique at 12 months of age.[16,17,18] According to the most current literature, early correction facilitates the development of orofacial functions, such as speech, swallowing, and breathing.[17,19]

Conclusion

Epignathus is a rare congenital oropharyngeal teratoma that was considered nonsurvivable in the past.[4] However, with the advancement of the prenatal evaluation and emergency actions by a multidisciplinary approach, there was a change in this scenario.[7,12] Complete resection of the tumor is imperative to prevent relapse, to maintain the airways free, and to provide a better oral function of the patient.[20]

References

- Ram, H.; Rawat, J.D.; Devi, S.; Singh, N.; Paswan, V.K.; Malkunje, L.R. Congenital large maxillary teratoma. Natl J Maxillofac Surg 2012, 3, 229–231. [Google Scholar]

- Morlino, S.; Castori, M.; Servadei, F.; Laino, L.; Silvestri, E.; Grammatico, P.; Pediatric Craniofacial Malformation (PECRAM) Study Group. Oropharyngeal teratoma, oral duplication, cervical diplomyelia and anencephaly in a 22-week fetus: a review of the craniofacial teratoma syndrome. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2015, 103, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patrocinio, L.G.; Patrocinio, T.G.; Coelho, S.R.; Patrocinio, J.A. Benign nasopharyngeal teratoma in an adult patient. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol (Engl Ed) 2008, 74, 477. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mahdi, A.H.; Al-Khurrhi, L.E.; Atto, G.Z.; Dhaher, A. Giant epignathus teratoma involving the palate, tongue, and floor of the mouth. J Craniofac Surg 2013, 24, e97–e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, Y.T.; Cala-Or, M.A.; Lui, C.C.; Wang, T.J.; Lai, J.P. Epignathus teratoma with duplication of mandible and tongue: report of a case. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2013, 50, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.M.; Veligandla, I.; Lakshmi, A.R.; Pandey, V. Congenital giant teratoma arising from the hard palate: a rare clinical presentation. J Clin Diagn Res 2016, 10, ED03–ED04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, C.H.P.; Nonaka, C.F.W.; Elias, C.T.V.; et al. Giant epignathus teratoma discovered at birth: a case report and 7-year follow-up. Braz Dent J 2017, 28, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jadhav, S.S.; Korday, C.S.; Malik, S.; Shah, V.K.; Lad, S.K. Epignathus leading to fatal airway obstruction in a neonate. J Clin Diagn Res 2017, 11, SD04–SD05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacs, H., Jr. Perinatal (fetal and neonatal) germ cell tumors. J Pediatr Surg 2004, 39, 1003–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, M.; Hegde, P.; Devaraju, U.M. Congenital facial teratoma. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2012, 11, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.C.; Gu, Y.Q.; Zhou, X.Y. Congenital giant epignathus with intracranial extension in a fetal. Chin Med J (Engl) 2017, 130, 2386–2387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Clement, K.; Chamberlain, P.; Boyd, P.; Molyneux, A. Prenatal diagnosis of an epignathus: A case report and review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2001, 18, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumiyoshi, S.; Machida, J.; Yamamoto, T.; et al. Massive immature teratoma in a neonate. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010, 39, 1020–1023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bader, D.; Riskin, A.; Vafsi, O.; et al. Alpha-fetoprotein in the early neonatal period–a large study and review of the literature. Clin Chim Acta 2004, 349, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenhaute, B.; Leteurtre, E.; Lecomte-Houcke, M.; et al. Epignathus teratoma: report of three cases with a review of the literature. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2000, 37, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemann, W.; Mossböck, R.; Kärcher, H.; Kozelj, V. Sagittal growth of the facial skeleton of 6-year-old children with a complete unilateral cleft of lip, alveolus and palate treated with two different protocols. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2007, 35, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neligan, P.C.; Rodriguez, E.D.; Losee, J.E. Plastic Surgery - Volume 3 (Craniofacial, Head and Neck Surgery), 3rd ed.Saunders: New York, NY, USA, 2013; 569–583. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, K.L.; Hardin-Jones, M.A.; Goldstein, J.A.; Halter, K.A.; Havlik, R.J.; Schulte, J. Timing of palatal surgery and speech outcome. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2008, 45, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johannisson, T.B.; Lohmander, A.; Persson, C. Assessing intelligibility by single words, sentences and spontaneous speech: A methodological study of the speech production of 10-year-olds. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol 2014, 39, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roby, B.B.; Scott, A.R.; Sidman, J.D.; Lander, T.A.; Tibesar, R.J. Complete peripartum airway management of a large epignathus teratoma: EXIT to resection. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2011, 75, 716–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the author. The Author(s) 2018.