Lignocellulosic Ethanol in a Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Obligation System—A Case Study of Swedish Sawdust Based-Ethanol Production

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Biofuel Policy in the EU and Sweden

2.2. Current Production and Use of Fuel Ethanol in the EU and Sweden

2.3. Advanced Ethanol Production

3. The Case Study: Ethanol from Sawdust

3.1. Raw Material Availability—Sawdust from Sawmills in a Forest Dense Region

3.2. The Ethanol Plant

3.3. Alternative Cases

4. Methods and Data Inventory

4.1. Revised Renewable Energy Directive (RED II)

4.2. LCA Data Inventory

4.3. The Swedish GHG Reduction Obligation System and Economic Background Data

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Ethanol Production and GHG Performance

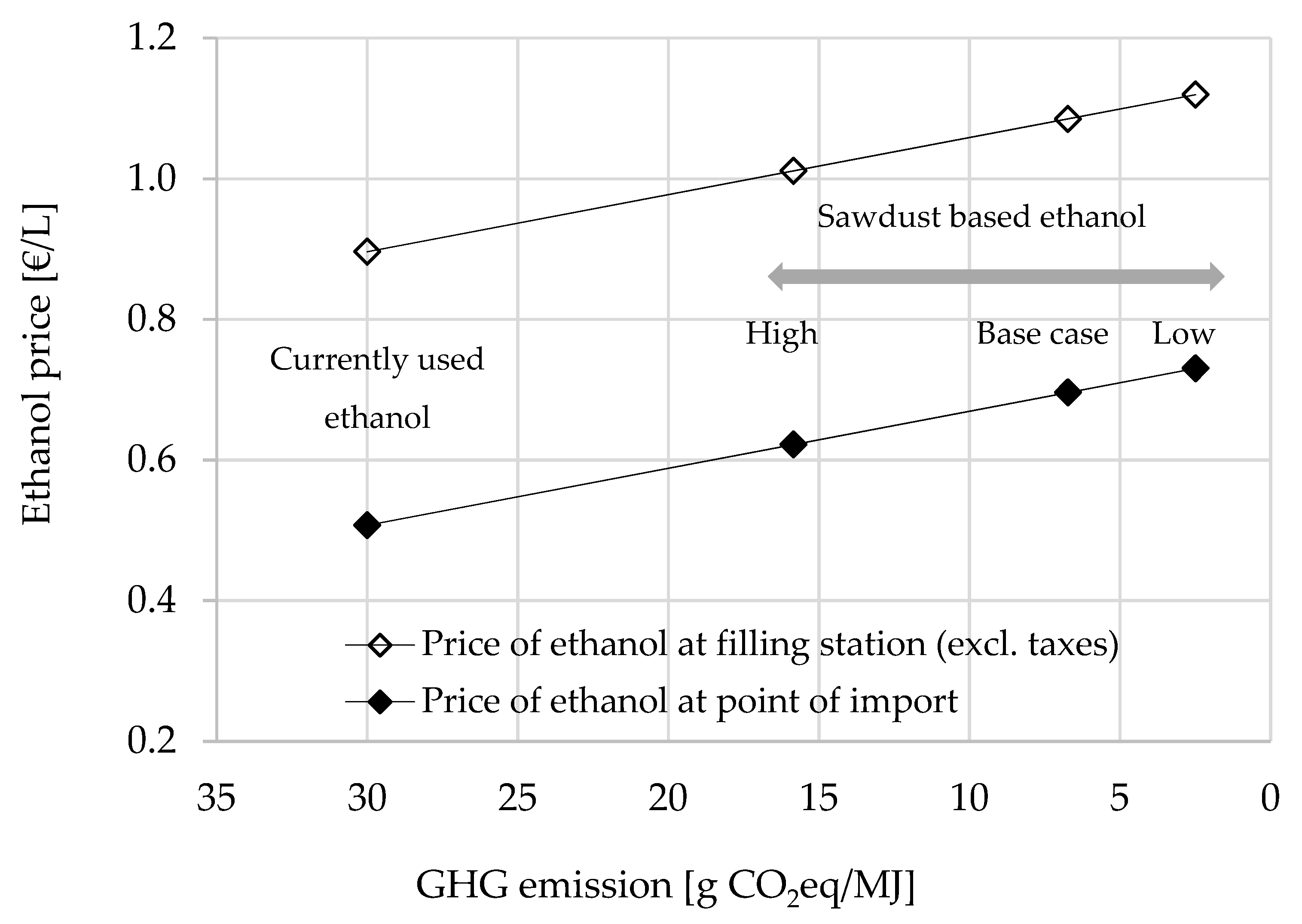

5.2. Economic Consequences of GHG Performance

6. Conclusions

- Sawdust-based ethanol can be produced with low life cycle GHG emission, leading to a GHG emission saving of 93% compared with fossil liquid transportation fuels, but it may vary between 83% and 97%.

- This, in turn, will increase the economic competitiveness of sawdust-based ethanol in the road transport sector under the Swedish GHG reduction obligation system, which promotes biofuels with low GHG emissions.

- Based on the current price of ethanol at point of import, and estimated future production costs of lignocellulosic ethanol in a large-scale developed market of advanced ethanol, calculations indicate that sawdust-based ethanol could become economically viable, and potentially also other lignocellulosic waste-based ethanol systems.

- However, in a short-term perspective, emerging sawdust-based ethanol production systems, as well as other lignocellulosic-based ethanol systems, are burdened with higher costs and economic risks and therefore need additional economic incentives to make a market introduction possible.

- The current GHG emission reduction obligation system in Sweden is a long-term stable political incentive, and seems to have the potential to promote future investments in lignocellulosic ethanol production systems in a developed, large-scale market.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Utilities | Input | Flow | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feedstock | Sawdust (DM) | 200,000 | t |

| Chemicals | Sulphur dioxide (liquid) | 2000 | t |

| Sodium hydroxide (50% wt.) | 6100 | t | |

| Sulphuric acid (50% wt.) | 960 | t | |

| Antifoam | 3200 | t | |

| Trace minerals | 0.2 | t | |

| Urea (40% wt.) | 12 | t | |

| Enzyme protein | 530 | t |

| Utilities | Input | Flow | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | Electricity | 89,600 | MWh |

| Steam (16 bar) | 350,000 | t | |

| Water | Process water | 883,000 | t |

| Boiler feed water (3 bar) | 97,000 | t |

References

- Börjesson, P. Potential för Ökad Tillförsel Och Avsättning av Inhemsk Biomassa i en Växande Svensk Bioekonomi. Report No 97; Environmental and Energy Systems Studies, Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018L2001&from=EN2018 (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- EEA Final Energy Consumption by Mode of Transport. European Energy Agency. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/transport-final-energy-consumption-by-mode/assessment-9 (accessed on 4 October 2019).

- Eurostat Share of Energy from Renewable Sources. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Renewable_energy_statistics (accessed on 7 October 2019).

- Drivmedel 2018. ER 2019:14; Swedish Energy Agency: Estone, Sweden, 2019.

- Andrén, R.; Westerberg, N. Kontrollstation 2019 för Reduktionsplikten. Reduktionspliktens Utveckling 2021–2030. Energimyndigheten; The Swedish Energy Agency: Eskilstuna, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Komplettering Till Kontrollstation 2019 för Reduktionsplikten; Swedish Energy Agency: Estone, Sweden, 2019.

- Börjesson, P.; Ahlgren, S.; Berndes, G. The climate benefit of Swedish ethanol: Present and prospective performance. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2012, 1, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ePURE European Renewable Ethanol—Key Figures 2018. Available online: https://epure.org/media/1920/190828-def-data-statistics-2018-infographic.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2019).

- St1 Cellunolix®. Available online: https://www.st1.eu/ (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- Galbe, M.; Zacchi, G. A review of the production of ethanol from softwood. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 59, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn-Hagerdal, B.; Karhumaa, K.; Fonseca, C.; Spencer-Martins, I.; Gorwa-Grauslund, M.F. Towards industrial pentose-fermenting yeast strains. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 74, 937–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taherzadeh, M.J.; Karimi, K. Acid-based hydrolysis processes for ethanol from lignocellulosic materials: A review. Bioresources 2007, 2, 472–499. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Q.; Appels, L.; Tan, T.; Dewil, R. Bioethanol from lignocellulosic biomass: Current findings determine research priorities. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padella, M.; O’Connell, A.; Prussi, M. What is still limiting the deployment of cellulosic ethanol? Analysis of the current status of the sector. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frankó, B.; Galbe, M.; Wallberg, O. Bioethanol production from forestry residues: A comparative techno-economic analysis. Appl. Energy 2016, 184, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joelsson, E.; Wallberg, O.; Börjesson, P. Integration potential, resource efficiency and cost of forest-fuel-based biorefineries. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2015, 82, 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwarsdotter, Y. Personal Communication; SEKAB: Örnsköldsvik, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Forestry Industries Skogsindustrierna. Available online: https://www.skogsindustrierna.se (accessed on 30 November 2019).

- Swedish Forest Agency Skogsstyrelsen—Statistik. Available online: https://www.skogsstyrelsen.se/statistik/ (accessed on 30 November 2019).

- Sågverk, Branschfakta Nr 1, Stockholm; Swedish Environmental Protection Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010.

- Ringman, M. Trädbränslesortiment: Definitioner Och Egenskaper; Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet, Institutionen för Virkeslära: Uppsala, Sweden, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Börjesson, P.; Gustavsson, L. Regional production and utilization of biomass in Sweden. Energy 1996, 21, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joelsson, J.; Di Fulvio, F.; De La Fuente, T.; Bergström, D.; Athanassiadis, D. Integrated supply of stemwood and residual biomass to forest-based biorefineries. Int. J. For. Eng. 2016, 27, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sassner, P.; Galbe, M.; Zacchi, G. Techno-economic evaluation of bioethanol production from three different lignocellulosic materials. Biomass Bioenergy 2008, 32, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.B.; Mueller, S.; Wang, M.; Han, J. Energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions from enzyme and yeast manufacture for corn and cellulosic ethanol production. Biotechnol. Lett. 2012, 34, 2259–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilpin, G.S.; Andrae, A.S. Comparative attributional life cycle assessment of European cellulase enzyme production for use in second-generation lignocellulosic bioethanol production. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 1034–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, R.; Bauen, A.; Shah, N. The greenhouse gas emissions performance of cellulosic ethanol supply chains in Europe. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2009, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Olofsson, J.; Barta, Z.; Börjesson, P.; Wallberg, O. Integrating enzyme fermentation in lignocellulosic ethanol production: Life-cycle assessment and techno-economic analysis. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moro, A.; Lonza, L. Electricity carbon intensity in European Member States: Impacts on GHG emissions of electric vehicles. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 64, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedish Energy Agency Nya Regler för Hållbarhetskriterier för Biodrivmedel Och Flytande Biobärnslen. Available online: https://www.energimyndigheten.se/ (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Vägledning Till Regelverket Om Hållbarhetskriterier för Biodrivmedel Och Flytande Biobränslen. ER 2012:27; Swedish Energy Agency: Estone, Sweden, 2012.

- Eriksson, E.; Gillespie, A.R.; Gustavsson, L.; Langvall, O.; Olsson, M.; Sathre, R.; Stendahl, J. Integrated carbon analysis of forest management practices and wood substitution. Can. J. For. Res. 2007, 37, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volvo Emissions from Volvo’s Trucks. Available online: www.volvotrucks.com (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- BioGrace BioGrace Version 4d. Available online: https://www.biograce.net/content/ghgcalculationtools/standardvalues (accessed on 30 November 2019).

- Ecoinvent Ecoinvent 3.5. Available online: https://www.ecoinvent.org/home.html (accessed on 26 November 2019).

- Dunn, J.B.; Adom, F.; Sather, N.; Han, J.; Snyder, S.; He, C.; Gong, J.; Yue, D.; You, F. Life-Cycle Analysis of Bioproducts and their Conventional Counterparts in GREET; Argonne National Lab.: Argonne, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Börjesson, P.; Tufvesson, L.; Lantz, M. Life Cycle Assessment of Biofuels in Sweden; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- El-Suleiman, A.; Anosike, N.; Pilidis, P. A preliminary assessment of the initial compression power requirement in CO2 pipeline Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technologies. Technologies 2016, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Övervakningsrapport Avseende Skattebefrielse för Flytande Biodrivmedel Under 2018. Report Nr 2019-002678; Swedish Energy Agency: Estone, Sweden, 2019.

- European Union Fuel Quality Directive 2009/30/ECof the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 Amending Directive 98/70/EC as Regards the Specification of Petrol, Diesel and Gas-Oil and Introducing a Mechanism to Monitor and Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Amending Council Directive 1999/32/EC as Regards the Specification of Fuel Used by Inland Waterway Vessels and Repealing Directive 93/12/EEC. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2009:140:0088:0113:EN:PDF (accessed on 23 April 2009).

- European Union Council Directive (EU) 2015/652 of 20 April 2015 Laying Down Calculation Methods and Reporting Requirements Pursuant to Directive 98/70/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council Relating to the Quality of Petrol and Diesel Fuels. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32015L0652&from=EN2015 (accessed on 20 April 2015).

- Swedish Tax Agency Skattesatser och Växelkurser. The Swedish Tax Agency. Available online: https://www.skatteverket.se/foretagochorganisationer/skatter/punktskatter/energiskatter/skattesatserochvaxelkurser.4.77dbcb041438070e0395e96.html (accessed on 13 November 2019).

- SPBI Utveckling av Försäljningspris för Bensin, Dieselbränsle Och Etanol. Available online: https://spbi.se/statistik/priser/ (accessed on 4 October 2019).

- Scenarier Över Sveriges Energisystem 2018; Swedish Energy Agency: Estone, Sweden, 2019.

- Becker, N.; Björnsson, L.; Börjesson, P. Greenhouse Gas Savings for Swedish Emerging Lignocellulose-Based Biofuels-Using the EU Renewable Energy Directive Calculation Methodology. Report No 104; Environmental and Energy Systems Studies, Lund Univeristy: Lund, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lantz, M.; Prade, T.; Ahlgren, S.; Björnsson, L. Biogas and ethanol from wheat grain or straw: Is there a trade-off between climate impact, avoidance of iLUC and production cost? Energies 2018, 11, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ISO, 14044: 2006. Environmental Management-Life Cycle Assessment-Requirements and Guidelines; European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Camia, A.; Robert, N.; Jonsson, R.; Pilli, R.; García-Condado, S.; López-Lozano, R.; Van der Velde, M.; Ronzon, T.; Gurría, P.; M’barek, R. Biomass Production, Supply, Uses and Flows in the European Union. First Results from an Integrated Assessment; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Soam, S.; Kapoor, M.; Kumar, R.; Borjesson, P.; Gupta, R.P.; Tuli, D.K. Global warming potential and energy analysis of second generation ethanol production from rice straw in India. Appl. Energy 2016, 184, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börjesson, P.; Lundgren, J.; Ahlgren, S.; Nyström, I. Sustainable Transportation Biofuels Today and in the Future: Summary; The Swedish Knowledge Centre for Renewable Transportation Fuels: Göteborg, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J.; Ou, X.; Chang, S.; Wu, M. Techno-economic analysis of bioethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass in China: Dilute-acid pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis of corn stover. Energies 2015, 8, 4096–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, J.D.; Mabee, W.E.; Saddler, J.N. Will second-generation ethanol be able to compete with first-generation ethanol? Opportunities for cost reduction. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2012, 6, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, J.D.; Mabee, W.E.; Saddler, J.N. The ability of cellulosic ethanol to compete for feedstock and investment with other forest bioenergy options. Ind. Biotechnol. 2014, 10, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedish Parliament Fossilfria drivmedel för att minska transportsektorns klimatpåverkan; Report 2017/18:RFR13; Traffic Committee: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018.

| Factor | Base Case | Alternative | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | Best available technology | A | Published data on commercial enzymes |

| Power production | Swedish electricity mix | B | Nordic electricity mix |

| Heat production | Stand-alone wood chip boiler | C | Internal use of lignin pellets |

| Feedstock availability | 2/3 (70 km transport distance) | D | 1/3 (100 km transport distance) |

| Transportation fuel | Swedish diesel blend | E | Biodiesel, HVO100 |

| CO2 capture | No capture | F | 30% capture and use |

| Input | [kg CO2-eq/kg] | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Sulphur dioxide | 0.36 | [36] |

| Sodium hydroxide | 0.95 | [36] |

| Sulphuric acid | 0.09 | [36] |

| Antifoam | 1.33 | [29] |

| Trace minerals | 0.44 | [37] |

| Urea | 2.63 | [36] |

| Enzymes: low carbon footprint | 6.05 a | [27] |

| Enzymes: Alternative A | 5.50 a | [29] |

| [g CO2-eq/MJ] | ||

| Swedish electricity mix | 13.1 | [30] |

| Nordic electricity mix | 34.9 | [32] |

| Heat (wood chip boiler) | 3.4 b | [38] |

| Diesel (77% diesel/23% biodiesel) | 77.2 | [5] |

| HVO100 | 8.8 | [5] |

| Parameter | Unit | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fossil petrol comparator | g CO2-eq/MJ | 93.3 | [41] |

| LHV petrol a | MJ/L | 32.2 | [42] |

| Tax (energy and CO2) b | €/L | 0.64 | [43] |

| Petrol price c | €/L | 0.59 | [44] |

| Current GHG emission from ethanol (2018) d | g CO2-eq/MJ | 30 | [6] |

| Current ethanol price at filling station (excl. taxes) c | €/L | 0.896 | [44] |

| Cost of domestic storage and distribution of ethanol e | €/L | 0.017 | [40] |

| Cost ethanol net margin (including profit) | €/L | 0.372 | [40] |

| Exchange rate | SEK/€ | 10.33 | [43] |

| Parameter | Unit | Fuel Ethanol | Sawdust-Based Ethanol | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Sweden, 2018 | High | Base Case | Low | ||

| Ethanol GHG emission | g CO2-eq/MJ | 30 | 15.8 | 6.7 | 2.5 |

| Ethanol blend-in | % energy | 6.2 | 5.1 | 4.5 | 4.3 |

| % volume | 9.2 | 7.6 | 6.8 | 6.5 | |

| Energy (Lower Heating Value) fuel blend | MJ/L | 31.2 | 31.4 | 31.4 | 31.5 |

| Price of fuel to customer (excl. taxes) a | €/GJ | 19.7 | |||

| Price of fuel to customer (excl. taxes) | €/L | 0.615 | 0.619 | 0.620 | 0.621 |

| Price of ethanol at filling station (incl. distribution and margin, etc.) | €/L | 0.90 | 1.01 | 1.09 | 1.12 |

| Price of ethanol at the point of import | €/L | 0.51 | 0.62 | 0.70 | 0.73 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haus, S.; Björnsson, L.; Börjesson, P. Lignocellulosic Ethanol in a Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Obligation System—A Case Study of Swedish Sawdust Based-Ethanol Production. Energies 2020, 13, 1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13051048

Haus S, Björnsson L, Börjesson P. Lignocellulosic Ethanol in a Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Obligation System—A Case Study of Swedish Sawdust Based-Ethanol Production. Energies. 2020; 13(5):1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13051048

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaus, Sylvia, Lovisa Björnsson, and Pål Börjesson. 2020. "Lignocellulosic Ethanol in a Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Obligation System—A Case Study of Swedish Sawdust Based-Ethanol Production" Energies 13, no. 5: 1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13051048

APA StyleHaus, S., Björnsson, L., & Börjesson, P. (2020). Lignocellulosic Ethanol in a Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Obligation System—A Case Study of Swedish Sawdust Based-Ethanol Production. Energies, 13(5), 1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13051048