The Relationships among Social, Environmental, Economic CSR Practices and Digitalization in Polish Energy Companies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. CSR Concept

2.1.1. Social Practices

- (1)

- assessment of the impact of activities undertaken by the enterprise on the local society,

- (2)

- cooperation on social and charity projects,

- (3)

- promotion of the development of the local community, protection of heritage,

- (4)

- ensuring work-family balance of employees,

- (5)

- ensuring a high level of work safety,

- (6)

- care for the development of the employees’ high competencies and care for the proper motivation of employees

- (7)

- conducting open cooperation with stakeholders.

2.1.2. Environmental Practices

- (1)

- assessing the environmental impact of activities,

- (2)

- introducing energy and water-saving activities,

- (3)

- developing renewable energy sources,

- (4)

- choosing environmentally friendly suppliers,

- (5)

- encouraging clients to care for the natural environment,

- (6)

- implementing waste and pollution control systems,

- (7)

- striving to reduce the environmental impact of energy production/transmission,

- (8)

- creating activities that care for the natural environment.

2.1.3. Economic Practices

- (1)

- offering a competitive level of remuneration,

- (2)

- treating customers and suppliers fairly,

- (3)

- shaping good relations with responsible suppliers,

- (4)

- providing high-quality products,

- (5)

- carrying out cost-effective operations,

- (6)

- investing in new technologies,

- (7)

- providing a high level of reliability of energy supplies,

- (8)

- managing financial risk.

2.2. The Rationale for CSR Concept in Energy Sector Companies

2.3. Digitalization of the Energy Sector

- in the production area: (a) optimization of the supply and management of fuel and spare parts, (b) preventive maintenance based on future market conditions;

- in the area of trade: (a) improving the decision-making process through the use of big-data technology and risk-management models, (b);

- in the area of energy transmission and distribution: (a) real-time remote monitoring to increase efficiency, (b) use of augmented reality tools to repair equipment in the field;

- in the sales area: (a) creating new products and services corresponding to the real needs of customers, (b) the use of business platforms connecting significant numbers of customers and suppliers.

2.4. CSR Practices and Digitalization

3. Methods and Research Sample

The Sample Selection and Description of the Research Tool

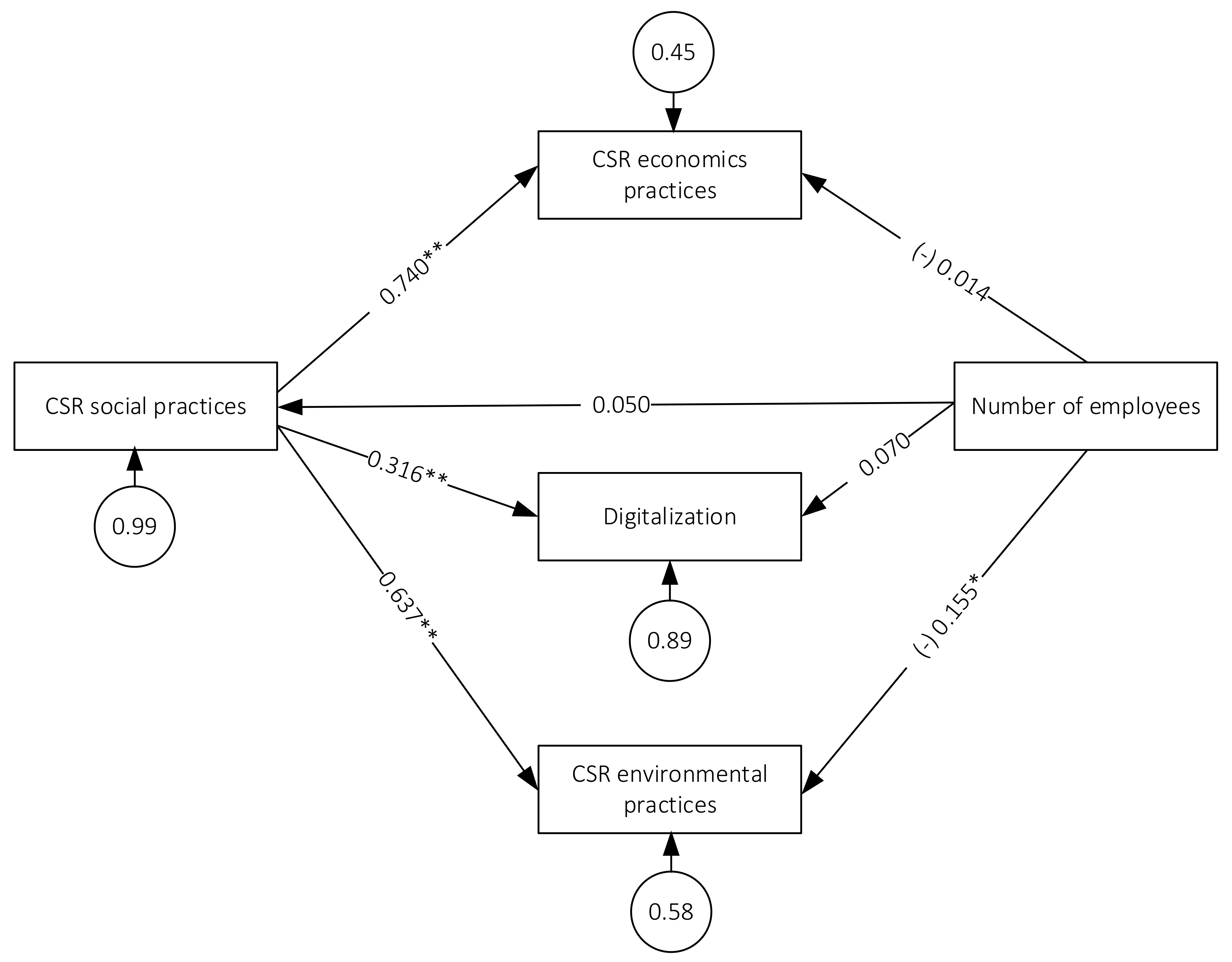

4. Research Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Research Questionnaire

- ☐

- The management team is considering implementing a digital transformation strategy in the long term, but currently this is not a strategic goal of the company.

- ☐

- The management team organizes the business conditions which are essential for carrying out digital transformation and prepares employees to implement this change. Employees are aware of the need to digitize the company’s operations.

- ☐

- The company uses modern ICT, processes are being automated, and there is cooperation with partners and research centres in order to improve the product manufacturing process.

- ☐

- The company’s employees use and create new technological solutions. Digitization occurs not only at the organizational level, but also at the individual level. It has become the foundation of the enterprise’s organizational culture.

| Please rate the degree to which you agree or disagree with each of the following statements Scale: 1—strongly disagree, 7—strongly agree |

| (1) In the activities undertaken in our company: |

| Environmental practices |

| We assess the environmental impact of our activities |

| We introduce energy and water saving activities |

| We develop renewable energy sources |

| We choose environmentally friendly suppliers |

| We encourage our clients to care for the natural environment |

| We implement waste and pollution control systems |

| We strive to reduce the environmental impact of energy production/transmission |

| We create activities that care for the natural environment |

| Social practices |

| We assess the impact of the activities undertaken on the local society |

| We cooperate on social and charity projects |

| We promote the development of the local community and heritage protection |

| We strive to ensure the work and family life balance of employees |

| We provide a high level of work safety |

| We care about the high competencies and proper motivation of employees |

| We interact openly with stakeholders |

| Economic practices |

| We offer a competitive level of remuneration |

| We treat customers and suppliers fairly |

| We shape good relations with responsible suppliers |

| We provide high quality products |

| We carry out cost-effective operations |

| We invest in new technologies |

| We provide a high level of reliability of energy supplies |

| We manage financial risk |

| (2) Formal CSR practices in our company are implemented under the influence of: |

| Relationship with the strategy |

| Relationship with organizational culture |

| Striving to reduce costs and ensure profitability |

| Environmental commitments and efforts to protect the climate |

| Protect yourself against potential risks |

| Image issues and reputation enhancement |

| Reporting important issues |

| Social requirements |

| Increase in competitiveness |

| Legal Requirements |

| Stakeholders’ expectations |

| Trends in management |

| (3) In our company, CSR practices have an impact on the actual change in the functioning of the company and are not symbolic in nature: |

| In the social dimension |

| In the economic dimension |

| In the environmental dimension |

| (4) CSR practices are particularly important for the long-term success of our company |

| In the social dimension |

| In the economic dimension |

| In the environmental dimension |

- Please indicate the age of your company:

- ☐

- Less than 2 years

- ☐

- 2–5 years

- ☐

- 6–10 years

- ☐

- 11–25 years

- ☐

- More than 25 years

- Please indicate the number of employees in your company:

- ☐

- 10–49

- ☐

- 50–249

- ☐

- More than 250

References

- Mitnick, B.M.; Windsor, D.; Wood, D.J. Csr: Undertheorized or essentially contested? Acad. Manag. Rev. 2021, 46, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulewicz-Sas, A. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Light of Management Science—Bibliometric Analysis. Procedia Eng. 2017, 182, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehy, B. Defining CSR: Problems and Solutions. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 131, 625–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Correlation or misspecification? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveson, L.; Joiner, T.A. Exploring corporate social responsibility values of millennial job-seeking students. Educ. Train. 2014, 56, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, S.; Zamir, N. Corporate social responsibility and institutional investors: The intervening effect of financial performance. J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2021, 37, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liczmańska-Kopcewicz, K.; Mizera, K.; Pypłacz, P. Corporate social responsibility and sustainable development for creating value for FMCG sector enterprises. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; van den Buuse, D. In search of viable business models for development: Sustainable energy in developing countries. Corp. Gov. 2012, 12, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.; Gallardo-Vazquez, D.; Dziwinski, P.; Barcik, A.; Sánchez-Hernández, M. Sustainable Development at Enterprise Level: CSR in Spain and Poland. Available online: https://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=14e18fb5-c3cc-4f9e-b4f3-ae7f85c3d877%40sdc-v-sessmgr02&bdata=Jmxhbmc9cGwmc2l0ZT1laG9zdC1saXZl#AN=80919153&db=obo (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Abdelhalim, K.; Eldin, A.G. Can CSR help achieve sustainable development? Applying a new assessment model to CSR cases from Egypt. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2019, 39, 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyeen, A.; West, B. Promoting CSR to foster sustainable development: Attitudes and perceptions of managers in a developing country. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2014, 6, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R. The Impact of CSR Efforts on Firm Performance in the Energy Sector. Ph.D. Thesis, George Fox University, Newberg, OR, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stjepcevic, J.; Siksnelyte, I. Corporate Social Responsibility in Energy Sector. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2017, 16, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Arena, M.; Azzone, G.; Mapelli, F. What drives the evolution of Corporate Social Responsibility strategies? An institutional logics perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hede Skagerlind, H.; Westman, M.; Berglund, H. Corporate Social Responsibility through Cross-sector Partnerships: Implications for Civil Society, the State, and the Corporate Sector in India. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2015, 120, 245–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezher, T.; Tabbara, S.; Al-Hosany, N. An overview of CSR in the renewable energy sector: Examples from the Masdar Initiative in Abu Dhabi. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2010, 21, 744–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Irfan Ahmed, R.; Ahmad, N.; Yan, C.; Usmani, M.S. Prioritizing critical success factors for sustainable energy sector in China: A DEMATEL approach. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2021, 35, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latapí Agudelo, M.A.; Johannsdottir, L.; Davidsdottir, B. Drivers that motivate energy companies to be responsible. A systematic literature review of Corporate Social Responsibility in the energy sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.; Qin, D.; Manning, M.; Chen, Z.; Marquis, M.; Averyt, K.B.; Tingor, M.; Miller, H.L. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Streimikiene, D.; Simanaviciene, Z.; Kovaliov, R. Corporate social responsibility for implementation of sustainable energy development in Baltic States. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Liang, M.; Zhang, C.; Rong, D.; Guan, H.; Mazeikaite, K.; Streimikis, J. Assessment of corporate social responsibility by addressing sustainable development goals. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 686–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwoda-Matiolanska, A.; Smolak-Lozano, E.; Nakayama, A. Corporate image or social engagement: Twitter discourse on corporate social responsibility (CSR) in public relations strategies in the energy sector. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuss, M.M.; Makieła, Z.J.; Herdan, A.; Kuźniarska, G. Energy Companies Obligation. Energies 2021, 14, 3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashtovaya, V. CSR reporting in the United States and Russia. Soc. Responsib. J. 2014, 10, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, A.S.; Orazalin, N.; Uyar, A.; Shahbaz, M. CSR achievement, reporting, and assurance in the energy sector: Does economic development matter ? Energy Policy 2020, 149, 112007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyaminova, A.; Mathews, M.; Langley, P.; Rieple, A. The impact of changes in stakeholder salience on corporate social responsibility activities in Russian energy firms: A contribution to the divergence/convergence debate. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1222–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengst, I.-A.; Muethel, M. Paradoxes and Dilemmas in Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy Execution. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2015, 2015, 14575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A. Key drivers endorsing CSR: A transition from economic to holistic approach. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 5, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaeian, V.; Khong, K.W.; Kyid Yeoh, K.; McCabe, S. Motivations of undertaking CSR initiatives by independent hotels: A holistic approach. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2468–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digitalization & Energy; IEA: Paris, France, 2017.

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, B.; Hartl, B. The perceived relationship between digitalization and ecological, economic, and social sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 315, 128128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.; Menichini, T. A multidimensional approach for CSR assessment: The importance of the stakeholder perception. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torugsa, N.A.; O’Donohue, W.; Hecker, R. Proactive CSR: An Empirical Analysis of the Role of its Economic, Social and Environmental Dimensions on the Association between Capabilities and Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 115, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyfert, S.; Glabiszewski, W.; Zastempowski, M. Impact of management tools supporting industry 4.0 on the importance of csr during covid-19. generation z. Energies 2021, 14, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delautre Bruno, G.; Abriata, D. Corporate Social Responsibility: Exploring Determinants and Complementarities; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Low, M.P. Corporate Social Responsibility and the Evolution of Internal Corporate Social Responsibility in 21st Century. Asian J. Soc. Sci. Manag. Stud. 2016, 3, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Yan, J.; Liu, T.; Huang, J. How does internal and external CSR affect employees’ work engagement? Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms and boundary conditions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papasolomou, I. The Practice of Internal Corporate Social Responsibility in SMEs in Cyprus. In Corporate Social Responsibility in Times of Crisis; Idowu, S.O., Vertigans, S., Burlea, A.S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 93–109. ISBN 9783319528397. [Google Scholar]

- Hiswåls, A.S.; Hamrin, C.W.; Vidman, Å.; Macassa, G. Corporate social responsibility and external stakeholders’ health and wellbeing: A viewpoint. J. Public Health Res. 2020, 9, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odongo, G.; Masinde, J.M.; Masese, E.R.; Abuya, W.O. The Impact of CSR on Corporate-Society Relations. J. Adv. Res. Sociol. 2019, 1, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Husted, B.W.; De Jesus Salazar, J. Taking friedman seriously: Maximizing profits and social performance. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.W.; Allen, D.B.; Kock, N. Value Creation Through Social Strategy. Bus. Soc. 2015, 54, 147–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.W.; Allen, D.B. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility and Value Creation among Large Firms. Lessons from the Spanish Experience. Long Range Plann. 2007, 40, 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacinello, E.; Tontini, G.; Alberton, A. Influence of corporate social responsibility on sustainable practices of small and medium-sized enterprises: Implications on business performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D.S.; Wright, P.M. Corporate social responsibility: Strategic implications. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ite, U.E. Multinationals and corporate social responsibility in developing countries: A case study of Nigeria. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2004, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giemza, M. Przyczyny oraz skutki implementacji zasad społecznej odpowiedzialności biznesu do zarządzania firmą. Ekon. Społeczna 2019, 2, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potočan, V.; Mulej, M.; Nedelko, Z. Society 5.0: Balancing of Industry 4.0, economic advancement and social problems. Kybernetes 2021, 50, 794–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzior, A.; Ober, J.; Karwot, J. Stakeholder expectation of corporate social responsibility practices: A case study of pwik rybnik, Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavra, J.; Bednarikova, M.; Munzarova, S.; Tetrevova, L. Relevant CSR activities for strengthening social profile of metallurgical company. In Proceedings of the METAL 2016—25th Anniversary International Conference on Metallurgy and Materials, Brno, Czech Republic, 25–27 May 2016; pp. 2061–2068. [Google Scholar]

- Amor-Esteban, V.; Galindo-Villardón, M.P.; García-Sánchez, I.M.; David, F. An extension of the industrial corporate social responsibility practices index: New information for stakeholder engagement under a multivariate approach. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grishnova, O.; Bereziuk, K.; Bilan, Y. Evaluation of the level of corporate social responsibility of Ukrainian nuclear energy producers. Manag. Mark. 2021, 16, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulema, T.F.; Roba, Y.T. Internal and external determinants of corporate social responsibility practices in multinational enterprise subsidiaries in developing countries: Evidence from Ethiopia. Futur. Bus. J. 2021, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinina, O. Analysis of trends and performance of CSR mining companies. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 302, 012120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaighum, S.A.K.; Ahmad, G.; Parveen, K. Workers’ Perceptions of CSR Practices: Analysis of a Textile Organization in Pakistan. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. Int. J. 2021, 13, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gadenne, D.L.; Kennedy, J.; McKeiver, C. An empirical study of environmental awareness and practices in SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Raya, M.; Martín-Tapia, I.; Ortiz-de-mandojana, N. To be or to seem: The role of environmental practices in corporate environmental reputation. Organ. Environ. 2019, 32, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorlakson, T.; Hainmueller, J.; Lambin, E.F. Improving environmental practices in agricultural supply chains: The role of company-led standards. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 48, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijatovic, I.; Maricic, M.; Horvat, A. The factors affecting the environmental practices of companies: The case of Serbia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlaner, L.M.; Berent-Braun, M.M.; Jeurissen, R.J.M.; de Wit, G. Beyond Size: Predicting Engagement in Environmental Management Practices of Dutch SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn, B.; Guerra, D.; van der Zwan, P. What drives environmental practices of SMEs? Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 44, 759–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, W.L.; Dooley, K.J.; Ellram, L.M. Transaction cost and institutional drivers of supplier adoption of environmental practices. J. Bus. Logist. 2011, 32, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, K.; Trendafilova, S. CSR and environmental responsibility: Motives and pressures to adopt green management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, D.A.H.; Eliwa, Y.; Power, D.M. The impact of corporate social and environmental practices on the cost of equity capital: UK evidence. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2019, 27, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seles, B.M.R.P.; Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Latan, H.; Roubaud, D. Do Environmental Practices Improve Business Performance Even in an Economic Crisis? Extending the Win-Win Perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 163, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; Potter, A. Environmental operations management and its links with proactivity and performance: A study of the UK food industry. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 170, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.M.; Ho, H. Who pays you to be green? How customers’ environmental practices affect the sales benefits of suppliers’ environmental practices. J. Oper. Manag. 2019, 65, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, L.; Font, X. Doing good to do well? Corporate social responsibility reasons, practices and impacts in small and medium accommodation enterprises. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currás-Pérez, R.; Dolz-Dolz, C.; Miquel-Romero, M.J.; Sánchez-García, I. How social, environmental, and economic CSR affects consumer-perceived value: Does perceived consumer effectiveness make a difference? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen McCain, S.L.; Lolli, J.C.; Liu, E.; Jen, E. The relationship between casino corporate social responsibility and casino customer loyalty. Tour. Econ. 2019, 25, 569–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lee, J.; Moon, S. Employee response to CSR in China: The moderating effect of collectivism. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 839–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Bashir, J. How does corporate social responsibility transform brand reputation into brand equity? Economic and noneconomic perspectives of CSR. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Mittal, S. Analysis of drivers of CSR practices’ implementation among family firms in India: A stakeholder’s perspective. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2019, 27, 947–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wut, T.M.; Xu, B.; Wong, H.S.M. A 15-year Review of “Corporate Social Responsibility Practices” Research in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Díaz-Fernández, M.C.; Simonetti, B. The social, economic and environmental dimensions of corporate social responsibility: The role played by consumers and potential entrepreneurs. Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 24, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.C.; Chiu, H.C.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Ho, P.S.; Chen, L.C.; Chang, W.C. The Perceptions and Expectations Toward the Social Responsibility of Hospitals and Organizational Commitment of Nursing Staff. J. Nurs. Res. 2016, 24, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, T.; Gadotti dos Anjos, S.J. Corporate Social Responsibility as Resource for Tourism Development Support. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Salmones, M.D.M.G.; Crespo, A.H.; Del Bosque, I.R. Influence of corporate social responsibility on loyalty and valuation of services. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ren, L.; Qiao, J.; Yao, S.; Strielkowski, W.; Streimikis, J. Corporate social responsibility and corruption: Implications for the sustainable energy sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, F.; de Arruda, M.P.; de Mascena, K.M.C.; Boaventura, J.M.G. Stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting: A classification model. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2071–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Mikhaylov, A.; Richter, U.H. Trade war effects: Evidence from sectors of energy and resources in Africa. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garstecki, D.; Kowalczyk, M.; Kwiecińska, K. CSR practices in Polish and Spanish stock listed companies: A comparative analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mory, L.; Wirtz, B.W.; Göttel, V. Factors of internal corporate social responsibility and the effect on organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 1393–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrjälä, J.; Takala, T. Before and after: Employees’ views on corporate social responsibility: Energysector stakeholders in Nordic postmerger integration. Soc. Responsib. J. 2009, 5, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, G.; Terwel, B.W.; Ellemers, N.; Daamen, D.D.L. Sustainability or profitability? How communicated motives for environmental policy affect public perceptions of corporate greenwashing. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekatah, I.; Samy, M.; Bampton, R.; Halabi, A. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability: The case of royal dutch shell plc. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2011, 14, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pätäri, S.; Arminen, H.; Tuppura, A.; Jantunen, A. Competitive and responsible? the relationship between corporate social and financial performance in the energy sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 37, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-P. Environmental responsibility, CEO power and financial performance in the energy sector. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021, 15, 2407–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pätäri, S.; Jantunen, A.; Kyläheiko, K.; Sandström, J. Does Sustainable Development Foster Value Creation? Empirical Evidence from the Global Energy Industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerckhoffs, T.; Wilde-Ramsing, J. European Works Councils and Corporate Social Responsibility in the European Energy Sector; EPSU: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Siano, A.; Conte, F.; Amabile, S.; Vollero, A.; Piciocchi, P. Communicating Sustainability: An Operational Model for Evaluating sustainability Communicating Sustainability: An Operational Model for Evaluating Corporate Websites. Sustainability 2016, 8, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, L. Disclosure of Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management: Evidence from China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 19, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ren, L.; Yao, S.; Qiao, J.; Strielkowski, W.; Streimikis, J. Comparative review of corporate social responsibility of energy utilities and sustainable energy development trends in the Baltic states. Energies 2019, 12, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, B.-S.; Feleaga, L.; Dumitrascu, L.-M. Does the shareholder salience influence the corporate social responsibility of entities from energy sector? In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Business Excellence 2020, Bucharest, Romania, 27 May 2020; pp. 225–235. [Google Scholar]

- Kittner, N.; Lill, F.; Kammen, D.M. Energy storage deployment and innovation for the clean energy transition. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 17125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliapietra, S.; Zachmann, G.; Edenhofer, O.; Glachant, J.M.; Linares, P.; Loeschel, A. The European union energy transition: Key priorities for the next five years. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 950–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostue, L.; Moengen, T. Digitalisation of the Energy Sector Recommendations for Research and Innovation Background; TANK Design: Oslo, Norway, 2021; ISBN 978-82-12-03850-9. [Google Scholar]

- Weigel, P.; Fischedick, M. Review and categorization of digital applications in the energy sector. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbach, K.; Rotaru, A.M.; Reichert, S.; Stiff, G.; Gölz, S. Which digital energy services improve energy efficiency? A multi-criteria investigation with European experts. Energy Policy 2018, 115, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhina, S.; Chadhar, M.; Vatanasakdakul, S.; Chetty, M. Challenges and opportunities for Blockchain Technology adoption: A systematic review. In Proceedings of the Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Perth, Australia, 9–11 August 2019; pp. 761–770. [Google Scholar]

- Alekseev, A.N.; Lobova, S.V.; Bogoviz, A.V.; Ragulina, Y.V. Digitalization of the Russian energy sector: State-of-the-art and potential for future research. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2019, 9, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burda, Y.D.; Volkova, I.O.; Gavrikova, E.V.; Kosygina, A.V. Digitalization and ways for the development of the electric energy industry with the participation of consumers: New challenges for shaping the investment climate. J. Sib. Fed. Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2019, 12, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gribanov, Y.; Shatrov, A. Modular digitalization of the energy sector. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 497, 012072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinos, P. Digitalization of Energy Sector; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ghobakhloo, M.; Fathi, M. Industry 4.0 and opportunities for energy sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akberdina, V.; Osmonova, A. Digital transformation of energy sector companies. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 250, 06001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenuga, O.T.; Mpofu, K.; Boitumelo, R.I. Energy efficiency analysis modelling system for manufacturing in the context of industry 4.0. Procedia CIRP 2019, 80, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyadin, S.; Suieubayeva, S.; Utegenova, A. Digital Transformation in Business; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 84, ISBN 9783030270155. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.; Woodhouse, S.; Sioshansi, F. Digitalization of energy. In Consumer Prosumer, Prosumager How Service Innovations Will Disrupt Utility Business Model; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, D.; Vartiainen, T. Changing Patterns in the Process of Digital Transformation Initiative in Established Firms: The Case of an Energy Sector Company; Association for Information Systems (AIS): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Industry 4.0. in the Energy Sector—BiznesAlert EN. Available online: https://biznesalert.com/industry-4-0-in-the-energy-sector/ (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Annunziata, M.; Bell, G.; Buch, R.; Patel, S.S. Powering the Future—Leading the Digital Transformation of the Power Industry; General Electric Company: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Loock, M. Unlocking the value of digitalization for the European energy transition: A typology of innovative business models. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 69, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcadell, F.J.; Aracil, E.; Úbeda, F. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability and Digitalization on International Banks’ Performance. Glob. Policy 2020, 11, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río Castro, G.; González Fernández, M.C.; Uruburu Colsa, Á. Unleashing the convergence amid digitalization and sustainability towards pursuing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A holistic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 122204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seele, P.; Lock, I. The game-changing potential of digitalization for sustainability: Possibilities, perils, and pathways. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latapí Agudelo, M.A.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Davídsdóttir, B. A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Velden, M. Maja Digitalisation and the UN Sustainable Development Goals: What role for design. Interact. Des. Archit. J. 2018, 37, 160–174. [Google Scholar]

- Belyaeva, Z.; Lopatkova, Y. The Impact of Digitalization and Sustainable Development Goals in SMEs’ Strategy: A Multi-Country European Study; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutani, S.; Paliwal, Y. Digitalization: A Step Towards Sustainable Development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 8, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, P.; Ricci, P. Cultural organizations, digital Corporate Social Responsibility and stakeholder engagement in virtual museums: A multiple case study. How digitization is influencing the attitude toward CSR. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehoff, S.; Beier, G. Industrie 4.0 and a sustainable development: A short study on the perception and expectations of experts in Germany. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 12, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.G.; Fischer, A. Digitization and Sustainability; ACCB Publishing: North Shields, UK, 2019; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, L.E. Evolution and revolution as organizations grow. 1972. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, D.; Lynch-Wood, G.; Ramsay, J. Drivers of environmental behaviour in manufacturing SMEs and the implications for CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bihari, S.C.; Pradhan, S. CSR and Performance: The Story of Banks in India. J. Transnatl. Manag. 2011, 16, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sila, I.; Cek, K. The Impact of Environmental, Social and Governance Dimensions of Corporate Social Responsibility on Economic Performance: Australian Evidence. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 120, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šontaitė-Petkevičienė, M. CSR Reasons, Practices and Impact to Corporate Reputation. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Sinha, P.; Chen, X. Corporate social responsibility and eco-innovation: The triple bottom line perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, W.S.; Smith, R.J. Social and Environmental Responsibility, Sustainability, and Human Resource Practices. SSRN Electron. J. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, A.; Falivena, C. Corporate social responsibility and firm value: Do firm size and age matter? Empirical evidence from European listed companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BarNir, A.; Gallaugher, J.M.; Auger, P. Business process digitization, strategy, and the impact of firm age and size: The case of the magazine publishing industry. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 6, 789–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, A.; Vitolla, F.; Rubino, M.; Giakoumelou, A.; Raimo, N. Online information on digitalisation processes and its impact on firm value. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions CSR | CSR Practices | |

|---|---|---|

| Economic practices |

| |

| Environmental practices |

| |

| Social practices |

| |

| Organization’s Age | |

|---|---|

| 0–5 years | 4.55% |

| 6–10 years | 24.55% |

| 11–25 years | 45.45% |

| more than 30 years | 25.45% |

| Number of Employees | |

| 10–49 | 50.00% |

| 50–249 | 24.55% |

| 250 and more | 25.45% |

| Indicator | Alpha Value |

|---|---|

| CSR economic practices | 0.899 |

| CSR environmental practices | 0.937 |

| CSR social practices | 0.875 |

| Variable | Digitalization | CSR Environmental Practices | CSR Social Practices | CSR Economic Practices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digitalization | 1.000 | 0.256 ** | 0.319** | 0.307 ** |

| CSR environmental practices | 0.256 ** | 1.000 | 0.629 ** | 0.573 ** |

| CSR social practices | 0.319 ** | 0.629 ** | 1.000 | 0.739 ** |

| CSR economics practices | 0.307 ** | 0.573 ** | 0.739 ** | 1.000 |

| R2 = 0.116 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | t-Statistic | p | |

| CSR environmental practices | 0.066 | 0.049 | 0.581 |

| CSR social practices | 0.173 | 0.154 | 0.239 |

| CSR economic practices | 0.141 | 0.135 | 0.310 |

| R2 = 0.102 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | t-Statistic | p | |

| CSR social practices | 0.319 | 3.504 | 0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chwiłkowska-Kubala, A.; Cyfert, S.; Malewska, K.; Mierzejewska, K.; Szumowski, W. The Relationships among Social, Environmental, Economic CSR Practices and Digitalization in Polish Energy Companies. Energies 2021, 14, 7666. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14227666

Chwiłkowska-Kubala A, Cyfert S, Malewska K, Mierzejewska K, Szumowski W. The Relationships among Social, Environmental, Economic CSR Practices and Digitalization in Polish Energy Companies. Energies. 2021; 14(22):7666. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14227666

Chicago/Turabian StyleChwiłkowska-Kubala, Anna, Szymon Cyfert, Kamila Malewska, Katarzyna Mierzejewska, and Witold Szumowski. 2021. "The Relationships among Social, Environmental, Economic CSR Practices and Digitalization in Polish Energy Companies" Energies 14, no. 22: 7666. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14227666

APA StyleChwiłkowska-Kubala, A., Cyfert, S., Malewska, K., Mierzejewska, K., & Szumowski, W. (2021). The Relationships among Social, Environmental, Economic CSR Practices and Digitalization in Polish Energy Companies. Energies, 14(22), 7666. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14227666