Molten Salts for Sensible Thermal Energy Storage: A Review and an Energy Performance Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Thermal Energy Storage Materials

- The energy storage density must be high for a compact design.

- For indirect TES systems, those where the energy storage medium is different from the heat transfer fluid (HTF) circulating through the solar field, a good heat transfer between HTF and TES material is needed to optimize the system’s efficiency.

- The TES material should be thermally stable and possess a low vapor pressure in the operating temperature range to avoid undesirable side effects such as material ageing, performance decline of the system, or GHG emissions.

- A high thermal, chemical, and cyclic stability for extended plant life should be expected.

- A non-flammable and non-toxic nature are desirable.

- Inexpensive and abundant.

- Specific heat capacity: this property controls the capacity of the temperature rise that can be transferred or stored. It improves the TES system efficiency [12].

- Melting temperature: this is directly related to operating and maintenance (O&M) costs since higher melting points need antifreeze protection.

- Decomposition temperature: this is the theoretical maximum operating temperature that must not be exceeded in order to keep the TES material operative and in good condition; the higher the maximum operating temperature, the higher the TES system efficiency achieved.

- Thermal conductivity: this property is related to the heat transfer behavior. Higher values are preferred in order to achieve higher heat exchange efficiency.

- Viscosity: this is directly related to the cost of pumping energy through the system, and lower values are preferable. It is also linked to the previous property, and a compromise between them should be taken.

- Density: this directly affects the specific energy that a selected TES material can store per unit of volume. The amount of heat carried by the HTF at working temperature relates to the density of a material and its specific heat capacity. Higher values are recommended.

2.1. Nitrate-Based Materials

- The kinetics degradation is also related to the surrounding atmosphere, its humidity, and CO2 content [52].

2.2. Chloride-Based Materials

2.3. Fluoride and Carbonate-Based Materials

3. Molten Salts Properties Enhancement

- Particle concentration, typically lower than 2%;

- Particle size, from 2 to 90 nm;

- Particle shape, mainly spherical or cylindrical;

- Particle type, oxides being the most popular, followed by carbon-based materials such as graphite or multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) and solid metals;

- Interaction between liquid and particles.

4. Energy and Cost Analysis of TES Materials

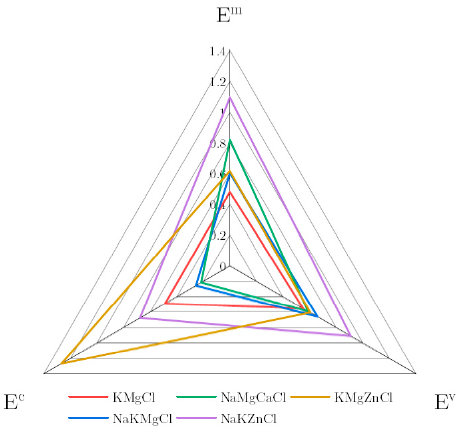

- Specific mass energy density Em (in MJ/kg): quantifies the amount of energy stored by the TES material in its operating temperature range and is defined in Equation (9).

- Specific volumetric energy density Ev (in MJ/m3): quantifies the same energy as the previous KPI, but in terms of volume (its definition is given in Equation (10)). This is helpful when estimating other KPIs in the TES system (i.e., confinement, land-area dimensions, and cost) and is useful in determining the flow rate and if it was going to be used as HTF.

- Energy storage cost Ec (in $/MJ): represents the direct cost of the stored energy and is defined in Equation (11).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Sisternes, F.J.; Jenkins, J.D.; Botterud, A. The value of energy storage in decarbonizing the electricity sector. Appl. Energy 2016, 175, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers, Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change; Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, U.; Kearney, D.W. Survey of Thermal Energy Storage for Parabolic Trough Power Plants. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2002, 124, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- IEA. Concentrating Solar Power, IEA Technology Roadmaps; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Cong, T.N.; Yang, W.; Tan, C.; Li, Y.; Ding, Y. Progress in electrical energy storage system: A critical review. Prog. Nat. Sci. 2009, 19, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Li, P.; Chan, C. Application of phase change materials for thermal energy storage in concentrated solar thermal power plants: A review to recent developments. Appl. Energy 2015, 160, 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, P.; Deydier, A.; Anxionnaz-Minvielle, Z.; Rougé, S.; Cabassud, M.; Cognet, P. A review on high temperature thermochemical heat energy storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 32, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laing, D.; Steinmann, W.-D.; Tamme, R.; Richter, C. Solid media thermal storage for parabolic trough power plants. Sol. Energy 2006, 80, 1283–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A.; Medrano, M.; Martorell, I.; Lázaro, A.; Dolado, P.; Zalba, B.; Cabeza, L.F. State of the art on high temperature thermal energy storage for power generation. Part 1—Concepts, materials and modellization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alva, G.; Liu, L.; Huang, X.; Fang, G. Thermal energy storage materials and systems for solar energy applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaimat, F.; Rashid, Y. Thermal Energy Storage in Solar Power Plants: A Review of the Materials, Associated Limitations, and Proposed Solutions. Energies 2019, 12, 4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernández, A.G.; Gomez-Vidal, J.; Oró, E.; Kruizenga, A.; Solé, A.; Cabeza, L.F. Mainstreaming commercial CSP systems: A technology review. Renew. Energy 2019, 140, 152–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alva, G.; Lin, Y.; Fang, G. An overview of thermal energy storage systems. Energy 2018, 144, 341–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2017; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, G.; Venkataraman, M.; Gomez-Vidal, J.; Coventry, J. Assessment of a novel ternary eutectic chloride salt for next generation high-temperature sensible heat storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 167, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffschmidt, B.; Tellez, F.M.; Valverde, A.; Fernandez, J.; Fernandez, V. Performance evaluation of the 200-kW(th) HiTRec-II open volumetric air receiver. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2003, 125, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, P.D., Jr.; Goswami, D.Y. Thermal energy storage using chloride salts and their eutectics. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 109, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, T.; Mantha, D.; Reddy, R.G. Novel high thermal stability LiF–Na2CO3–K2CO3 eutectic ternary system for thermal energy storage applications. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2015, 140, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bauer, T.; Pfleger, N.; Breidenbach, N.; Eck, M.; Laing, D.; Kaesche, S. Material aspects of Solar Salt for sensible heat storage. Appl. Energy 2013, 111, 1114–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raade, J.W.; Padowitz, D. Development of Molten Salt Heat Transfer Fluid with Low Melting Point and High Thermal Stability. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2011, 133, 031013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, R.; Meeker, D. High-temperature stability of ternary nitrate molten salts for solar thermal energy systems. Sol. Energy Mater. 1990, 21, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.Y.; Wu, Z.G. Thermal property characterization of a low melting temperature ternary nitrate salt mixture for thermal energy storage systems. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2011, 95, 3341–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Mantha, D.; Reddy, R.G. Thermal stability of the eutectic composition in LiNO3–NaNO3–KNO3 ternary system used for thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2012, 100, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscia, K.; Nelle, S.; Elliott, T.; Mohapatra, S.; Oztekin, A.; Neti, S. Thermophysical properties of Li-NO3–NaNO3–KNO3 mixtures for use in concentrated solar power. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2013, 135, 4024069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Ding, J.; Wei, X.; Jiang, G. Thermodynamic Investigation of the Eutectic Mixture of the Li-NO3-NaNO3-KNO3-Ca(NO3)2 System. Int. J. Thermophys. 2017, 38, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Mantha, D.; Reddy, R.G. Novel low melting point quaternary eutectic system for solar thermal energy storage. Appl. Energy 2013, 102, 1422–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Li, P.; Hao, Q.; Xiao, B. Survey and evaluation of equations for thermophysical properties of binary/ternary eutectic salts from NaCl, KCl, MgCl2, CaCl2, ZnCl2 for heat transfer and thermal storage fluids in CSP. Sol. Energy 2017, 152, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, J.C.; Klammer, N. Molten chloride technology pathway to meet the U.S. DOE sunshot initiative with Gen3 CSP. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2126, p. 080006. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Song, M.; Wang, W.; Ding, J.; Yang, J. Design and thermal properties of a novel ternary chloride eutectics for high-temperature solar energy storage. Appl. Energy 2015, 156, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Tian, H.; Wang, W.; Ding, J.; Wei, X.; Song, M. Thermal stability of the eutectic composition in NaCl-CaCl2-MgCl2 ternary system used for thermal energy storage applications. Energy Procedia 2017, 105, 4185–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Ding, J.; Tian, H.; Wang, W.; Wei, X.; Song, M. Thermal properties and thermal stability of the ternary eutectic salt NaCl-CaCl2-MgCl2 used in high-temperature thermal energy storage process. Appl. Energy 2017, 204, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Molina, E.; Wang, K.; Xu, X.; Dehghani, G.; Kohli, A.; Hao, Q.; Kassaee, M.H.; Jeter, S.M.; Teja, A.S. Thermal and Transport Properties of NaCl–KCl–ZnCl2 Eutectic Salts for New Generation High-Temperature Heat-Transfer Fluids. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2016, 138, 054501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3Forsberg, C.W.; Peterson, P.F.; Zhao, H. High-Temperature Liquid-Fluoride-Salt Closed-Brayton-Cycle Solar Power Towers. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2006, 129, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-López, R.; Fradera, J.; Cuesta-López, S. Molten salts database for energy applications. Chem. Eng. Process. Process. Intensif. 2013, 73, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jerden, J. Molten Salt Thermophysical Properties Database Development: 2019 Update; 2019 Update (No. ANL/CFCT-19/6); Argonne National Laboratory (ANL): Argonne, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- An, X.-H.; Cheng, J.-H.; Su, T.; Zhang, P. Determination of thermal physical properties of alkali fluoride/carbonate eutectic molten salt. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 1850, p. 070001. [Google Scholar]

- Zavoico, A.B. Design Basis Document SAND2001–2100; Sandia National Laboratories: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Boerema, N.; Morrison, G.; Taylor, R.; Rosengarten, G. Liquid sodium versus Hitec as a heat transfer fluid in solar thermal central receiver systems. Sol. Energy 2012, 86, 2293–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, N.P.; Bradshaw, R.W.; Cordaro, J.B.; Kruizenga, A.M. Thermophysical property measurement of nitrate salt heat transfer fluids. In Proceedings of the ASME 2011 5th International Conference on Energy Sustainability, Washington, DC, USA, 7–10 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Roget, F.; Favotto, C.; Rogez, J. Study of the KNO3–LiNO3 and KNO3–NaNO3–LiNO3 eutectics as phase change materials for thermal storage in a low-temperature solar power plant. Sol. Energy 2013, 95, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Leng, G.; Ye, F.; Ge, Z.; Liu, C.; Wang, L.; Ding, Y. Form-stable LiNO3–NaNO3–KNO3–Ca (NO3)2/calcium silicate composite phase change material (PCM) for mid-low temperature thermal energy storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 106, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordaro, J.G.; Rubin, N.C.; Bradshaw, R.W. Multicomponent Molten Salt Mixtures Based on Nitrate/Nitrite Anions. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2011, 133, 011014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Li, P.; Li, Y.; Hao, Q.; Xiao, B.; Elsentriecy, H.; Gervasio, D. Experimental Test of Properties of KCl–MgCl2 Eutectic Molten Salt for Heat Transfer and Thermal Storage Fluid in Concentrated Solar Power Systems. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2018, 140, 051011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Dehghani, G.; Ning, J.; Li, P. Basic properties of eutectic chloride salts NaCl-KCl-ZnCl2 and NaCl-KCl-MgCl2 as HTFs and thermal storage media measured using simultaneous DSC-TGA. Sol. Energy 2018, 162, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.F.; Toth, L.M.; Clarno, K.T. Assessment of Candidate Molten Salt Coolants for the Advanced High Temperature Reactor (AHTR); Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2006; pp. 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, R.W.; Siegel, N.P. Molten nitrate salt development for thermal energy storage in parabolic trough solar power systems. In Proceedings of the ASME 2008 2nd International Conference on Energy Sustainability, Jacksonville, FL, USA, 10–14 August 2008; ASME International: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 631–637. [Google Scholar]

- Glatzmaier, G.N.; Siegel, N.P. Molten Salt Heat Transfer Fluids and Thermal Storage Technology Sandia Technical Report; SAND2010-3826C; Sandia National Laboratories: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mehos, M.; Turchi, C.; Vidal, J.; Wagner, M.; Ma, Z.; Ho, C.; Kolb, W.; Andraka, C.; Kruizenga, A. Concentrating Solar Power Gen3 Demonstration Roadmap; (No. NREL/TP-5500-67464); National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Walczak, M.; Pineda, F.; Fernández-Ángel, G.; Mata-Torres, C.; Escobar, R.A. Materials corrosion for thermal energy storage systems in concentrated solar power plants. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 86, 22–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tian, J.; Xu, K.; Gao, Y. Thermodynamic evaluation of phase equilibria in NaNO3-KNO3 system. J. Phase Equilibria Diffus. 2003, 24, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sau, S.; Corsaro, N.; Crescenzi, T.; D’Ottavi, C.; Liberatore, R.; Licoccia, S.; Russo, V.; Tarquini, P.; Tizzoni, A. Techno-economic comparison between CSP plants presenting two different heat transfer fluids. Appl. Energy 2016, 168, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, R.I. The thermal stability of molten nitrite/nitrates salt for solar thermal energy storage in different atmos-pheres. Sol. Energy 2012, 86, 2576–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E.S. The Kinetics of the Thermal Decomposition of Potassium Nitrate and of the Reaction between Potassium Nitrite and Oxygen1a. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 838–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruizenga, A.M.; Cordaro, J.G. Preliminary Development of Thermal Stability Criterion for Alkali Nitrates; Sandia Technical Report SAND2011-5837C; Sandia National Laboratories: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, T.; Laing, D.; Tamme, R. Characterization of Sodium Nitrate as Phase Change Material. Int. J. Thermophys. 2012, 33, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignarooban, K.; Xu, X.; Arvay, A.; Hsu, K.; Kannan, A. Heat transfer fluids for concentrating solar power systems—A review. Appl. Energy 2015, 146, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E.S. The Kinetics of the Thermal Decomposition of Sodium Nitrate and of the Reaction between Sodium Nitrite and Oxygen. J. Phys. Chem. 1956, 60, 1487–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; Ushak, S.; Galleguillos, H.R.; Pérez, F. Development of new molten salts with LiNO3 and Ca(NO3)2 for energy storage in CSP plants. Appl. Energy 2014, 119, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordaro, J.G.; Rubin, N.C.; Sampson, M.D.; Bradshaw, R.W. Multi-component molten salt mixtures based on ni-trate/nitrite anions. In Proceedings of the 6th Electronic Proceedings SolarPaces, Perpignan, France, 21–24 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Villada, C.; Bonk, A.; Bauer, T.; Bolívar, F. High-temperature stability of nitrate/nitrite molten salt mixtures under different atmospheres. Appl. Energy 2018, 226, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-T.; Li, Y.; Ren, N.; Ma, C.-F. Improving the thermal properties of NaNO3-KNO3 for concentrating solar power by adding additives. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 160, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonk, A.; Sau, S.; Uranga, N.; Hernaiz, M.; Bauer, T. Advanced heat transfer fluids for direct molten salt line-focusing CSP plants. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2018, 67, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonk, A.; Braun, M.; Sötz, V.A.; Bauer, T. Solar Salt—Pushing an old material for energy storage to a new limit. Appl. Energy 2020, 262, 114535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; Carbajo, R.; Crutchik, M.; Galleguillos, H.; Fuentealba, E. Modular Solar Storage System for Medium Scale Energy Demand Mining in the North of Chile. Energy Procedia 2015, 69, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cáceres, G.; Montané, M.; Nasirov, S.; O’Ryan, R. Review of Thermal Materials for CSP Plants and LCOE Evaluation for Performance Improvement using Chilean Strategic Minerals: Lithium Salts and Copper Foams. Sustainability 2016, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olivares, R.I.; Edwards, W. LiNO3–NaNO3–KNO3 salt for thermal energy storage: Thermal stability evaluation in different atmospheres. Thermochim. Acta 2013, 560, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Uwaisg, J.; Jin, Y.; An, X. Evaluation of thermal physical properties of molten nitrate salts with low melting temperature. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 176, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, J.C.; Calvet, N.; Starace, A.K.; Glatzmaier, G.C. Ca(NO3)2—NaNO3—KNO3 Molten Salt Mixtures for Direct Thermal Energy Storage Systems in Parabolic Trough Plants. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2013, 135, 021016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, S.; Li, P. Digital phase diagram and thermophysical properties of KNO3-NaNO3-Ca(NO3)2 ternary system for solar energy storage. Vacuum 2017, 145, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.F. Assessment of Candidate Molten Salt Coolants for the NGNP/NHI Heat-Transfer Loop; No. ORNL/TM-2006/69; Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL): Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Le Brun, C. Molten salts and nuclear energy production. J. Nucl. Mater. 2007, 360, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohan, G.; Venkataraman, M.B.; Coventry, J. Sensible energy storage options for concentrating solar power plants operating above 600 °C. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 107, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenhorst, H.; Böhmer, T. Enthalpy of fusion prediction for the economic optimisation of salt based latent heat thermal energy stores. J. Energy Storage 2018, 20, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; Li, P.; Wang, K.; Molina, E.E. Survey of properties of key single and mixture halide salts for potential ap-plication as high temperature heat transfer fluids for concentrated solar thermal power systems. AIMS Energy 2014, 2, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohal, M.S.; Ebner, M.A.; Sabharwall, P.; Sharpe, P. Engineering Database of Liquid Salt Thermophysical and Ther-Mochemical Properties; No. INL/EXT-10-18297; Idaho National Laboratory: Idaho Falls, ID, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Song, M.; Ding, J.; Yang, J. Quaternary chloride eutectic mixture for thermal energy storage at high tem-perature. Energy Procedia 2015, 75, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robelin, C.; Chartrand, P. Thermodynamic evaluation and optimization of the (NaCl+ KCl+ MgCl2+ CaCl2+ ZnCl2) system. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2011, 43, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S.; Spiegel, M. Models describing the degradation of FeAl and NiAl alloys induced by ZnCl2-KCl melt at 400–450 °C. Corros. Sci. 2004, 46, 2009–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wei, X.; Wang, W.; Lu, J.; Ding, J. Corrosion behavior of Ni-based alloys in molten NaCl-CaCl2-MgCl2 eutectic salt for concentrating solar power. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 170, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Zhang, C.Z.; Li, Z.H.; Zhou, H.X.; He, J.X.; Yu, J.C. Corrosion behavior of nickel-based superalloys in thermal storage medium of molten eutectic NaCl-MgCl2 in atmosphere. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 164, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Zhou, H.X.; Zhang, C.Z.; Liu, W.N.; Zhao, B.Y. Influence of MgCl2 content on corrosion behavior of GH1140 in molten NaCl- MgCl2 as thermal storage medium. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 179, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Bonk, A.; Bauer, T. Corrosion behavior of metallic alloys in molten chloride salts for thermal energy storage in concentrated solar power plants: A review. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2018, 12, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dicks, A.L. Molten carbonate fuel cells. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2004, 8, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lageraaen, P.; Patel, B.; Kalb, P.; Adams, J. Treatability Studies for Polyethylene Encapsulation of INEL Low-Level Mixed Wastes. Treatability Studies for Polyethylene Encapsulation of INEL Low-Level Mixed Wastes; Final Report (No. BNL-62620); Brookhaven National Laboratory: Upton, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosek, J.; Anderson, M.; Sridharan, K.; Allen, T. Current Status of Knowledge of the Fluoride Salt (FLiNaK) Heat Transfer. Nucl. Technol. 2009, 165, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, R.I.; Chen, C.; Wright, S. The Thermal Stability of Molten Lithium–Sodium–Potassium Carbonate and the Influence of Additives on the Melting Point. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2012, 134, 041002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Tran, T.; Olivares, R.; Wright, S.; Sun, S. Coupled Experimental Study and Thermodynamic Modeling of Melting Point and Thermal Stability of Li2CO3-Na2CO3-K2CO3 Based Salts. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2014, 136, 031017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-T.; Ren, N.; Wang, T.; Ma, C.-F. Experimental study on optimized composition of mixed carbonate salt for sensible heat storage in solar thermal power plant. Sol. Energy 2011, 85, 1957–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xie, L. Experimental investigation and thermodynamic modeling of an innovative molten salt for thermal energy storage (TES). Appl. Energy 2018, 212, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhang, J.; Wu, W.; Zhou, W. Corrosion in the molten fluoride and chloride salts and materials development for nuclear applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 97, 448–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangini, S. Corrosion of metallic stack components in molten carbonates: Critical issues and recent findings. J. Power Sources 2008, 182, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Uematsu, K.; Toda, K.; Sato, M. Viscosity analysis of alkali metal carbonate molten salts at high tem-perature. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2015, 123, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keblinski, P.; Eastman, J.A.; Cahill, D.G. Nanofluids for thermal transport. Mater. Today 2005, 8, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Banerjee, D. Enhancement of specific heat capacity of high-temperature silica-nanofluids synthesized in alkali chloride salt eutectics for solar thermal-energy storage applications. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2011, 54, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, O.; Karim, M. An investigation into the thermophysical and rheological properties of nanofluids for solar thermal applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Awad, A.; Navarro, H.; Ding, Y.; Wen, D. Thermal-physical properties of nanoparticle-seeded nitrate molten salts. Renew. Energy 2018, 120, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Choi, S.U.S. Thermal Conductivity of Nanoparticle—Fluid Mixture. J. Thermophys. Heat Transf. 1999, 13, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshed, S.; Leong, K.; Yang, C. Investigations of thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2008, 47, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoms, M.W. Adsorption at the Nanoparticle Interface for Increased Thermal Capacity in Solar Thermal Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.; Banerjee, D. Enhanced Specific Heat of Silica Nanofluid. J. Heat Transf. 2010, 133, 024501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.-C.; Huang, C.-H. Specific heat capacity of molten salt-based alumina nanofluid. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Das, S.K.; Putra, N.; Thiesen, P.; Roetzel, W. Temperature Dependence of Thermal Conductivity Enhancement for Nanofluids. J. Heat Transf. 2003, 125, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gu, H.; Fujii, M. Effective thermal conductivity and thermal diffusivity of nanofluids containing spherical and cylindrical nanoparticles. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2007, 31, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, C.-Y.; He, Y.; Yang, W.; Lee, W.P.; Zhang, L.; Huo, R. Heat Transfer Intensification Using Nanofluids. KONA Powder Part. J. 2007, 25, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muñoz-Sánchez, B.; Nieto-Maestre, J.; Iparraguirre-Torres, I.; García-Romero, A.; Sala-Lizarraga, J.M. Molten salt-based nanofluids as efficient heat transfer and storage materials at high temperatures. An overview of the literature. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 3924–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieruzzi, M.; Cerritelli, G.F.; Miliozzi, A.; Kenny, J.M. Effect of nanoparticles on heat capacity of nanofluids based on molten salts as PCM for thermal energy storage. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schuller, M.; Shao, Q.; Lalk, T. Experimental investigation of the specific heat of a nitrate–alumina nanofluid for solar thermal energy storage systems. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2015, 91, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andreu-Cabedo, P.; Mondragon, R.; Hernandez, L.; Martinez-Cuenca, R.; Cabedo, L.; Julia, J.E. Increment of specific heat capacity of solar salt with SiO2 nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Gao, L.; Wang, M. Nitrate based nanocomposite thermal storage materials: Understanding the enhancement of thermophysical properties in thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2020, 216, 110727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaradjane, R.; Shin, D. Nanoparticle Dispersions on Ternary Nitrate Salts for Heat Transfer Fluid Applications in Solar Thermal Power. J. Heat Transf. 2016, 138, 051901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Shin, D. Enhancement of specific heat of ternary nitrate (LiNO3-NaNO3-KNO3) salt by doping with SiO2 nanoparticles for solar thermal energy storage. Micro Nano Lett. 2014, 9, 817–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changla, S. Experimental Study of Quaternary Nitrate/Nitrite Molten Salt as Advanced Heat Transfer Fluid and Energy Storage Material in Concentrated Solar Power Plant. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Texas, Arlington, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.; Banerjee, D. Enhanced Specific Heat Capacity of Molten Salt-Metal Oxide Nanofluid as Heat Transfer Fluid for Solar Thermal Applications; (No. 2010-01-1734); SAE Technical Paper; SAE: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, A.W.; Zheng, T.; Zavala, V.M. Economic assessment of concentrated solar power technologies: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 1019–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, G.; Venkataraman, M.; Gomez-Vidal, J.; Coventry, J. Thermo-economic analysis of high-temperature sensible thermal storage with different ternary eutectic alkali and alkaline earth metal chlorides. Sol. Energy 2018, 176, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiznobaik, H.; Shin, D. Enhanced specific heat capacity of high-temperature molten salt-based nanofluids. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2013, 57, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrado, C.; Marzo, A.; Fuentealba, E.; Fernández, A. 2050 LCOE improvement using new molten salts for thermal energy storage in CSP plants. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S. Thermal Cycling Effect on the Nanoparticle Distribution and Specific Heat of a Carbonate Eutectic with Alumina Nanoparticles. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Romaní, J.; Gasia, J.; Solé, A.; Takasu, H.; Kato, Y.; Cabeza, L.F. Evaluation of energy density as performance indicator for thermal energy storage at material and system levels. Appl. Energy 2019, 235, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, B.; Banerjee, D. Viscosity measurements of multi-walled carbon nanotubes-based high temperature nanofluids. Mater. Lett. 2014, 122, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Jo, B.; Kwak, H.-E.; Banerjee, D. Investigation of High Temperature Nanofluids for Solar Thermal Power Conversion and Storage Applications. In Proceedings of the 2010 14th International Heat Transfer Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 8–13 August 2010; pp. 583–591. [Google Scholar]

- Turchi, C.S.; Vidal, J.; Bauer, M. Molten salt power towers operating at 600–650 °C: Salt selection and cost benefits. Sol. Energy 2018, 164, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumashev, A.; Ślusarczyk, B.; Kondrashev, S.; Mikhaylov, A. Global Indicators of Sustainable Development: Evaluation of the Influence of the Human Development Index on Consumption and Quality of Energy. Energies 2020, 13, 2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrifech, S.; Agalit, H.; Bennouna, E.G.; Mimet, A. Selection methodology of potential sensible thermal energy storage materials for medium temperature applications. In MATEC Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2020; Volume 307, p. 01026. [Google Scholar]

- Madaeni, S.H.; Sioshansi, R.; Denholm, P. How thermal energy storage enhances the economic viability of concen-trating solar power. Proc. IEEE 2011, 100, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.J.; Rubin, E.S. Economic implications of thermal energy storage for concentrated solar thermal power. Renew. Energy 2014, 61, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Roubaud, E.; Pérez-Osorio, D.; Prieto, C. Review of commercial thermal energy storage in concentrated solar power plants: Steam vs. molten salts. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Bonk, A.; Bauer, T. Molten chloride salts for next generation CSP plants: Selection of promising chloride salts & study on corrosion of alloys in molten chloride salts. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2126, p. 200014. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.F.; Clarno, K.T. Evaluation of Salt Coolants for Reactor Applications. Nucl. Technol. 2008, 163, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| %Weight | Fusion Temperature (°C) | Decomposition Temperature (°C) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrate-based | ||||

| Solar Salt | 60 NaNO3–40 KNO3 | 240 | 565 | [19] |

| Hitec | 7 NaNO3–53 KNO3–40 NaNO2 | 142 | 450 | [20] |

| Hitec XL | 15 NaNO3–43 KNO3–42 Ca(NO3)2 | 130 | 450 | [21,22] |

| LiNaKNO3 | 30 LiNO3–18 NaNO3–52 KNO3 | 118 | 550 | [23,24] |

| LiNaKCaNO3 | 15.5 LiNO3–8.2 NaNO3–54.3 KNO3–22 Ca(NO3)2 | 93 | 450 | [25] |

| LiNaKNO3NO2 | 9 LiNO3–42.3 NaNO3–33.6 KNO3–15.1 KNO2 | 97 | 450 | [26] |

| Chloride-based | ||||

| KMgCl | 62.5 KCl–37.5 MgCl2 | 430 | >700 | [27] |

| NaKMgCl | 20.5 NaCl–30.9 KCl–48.6 MgCl2 | 383 | >700 | [27,28] |

| NaMgCaCl | 39.6 NaCl–39 MgCl2–21.4 CaCl2 | 407 | 650 | [29,30,31] |

| NaKZnCl | 7.5 NaCl–23.9 KCl–68.6 ZnCl2 | 204 | >700 | [31,32] |

| KMgZnCl | 49.4 KCl–15.5 MgCl2–35.1 ZnCl2 | 356 | >700 | [31,32] |

| Fluoride-based | ||||

| LiNaKF | 29.2 LiF–11.7 NaF–59.1 KF | 454 | >700 | [33] |

| NaBF | 3 NaF–97 NaBF4 | 385 | >700 | [34] |

| KBF | 13 KF–87 KBF4 | 460 | >700 | [35] |

| KZrF | 32.5 KF–67.5 ZrF4 | 420 | >700 | [34] |

| Carbonate-based | ||||

| LiNaKCO3 | 32.1 Li2CO3–33.4 Na2CO3–34.5 K2CO3 | 397 | 670 | [36] |

| Density (kg/m3) | Specific Heat Capacity (J/kg°C) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrate-based | |||

| Solar Salt | 2090 − 0.636T | 1443 + 0.172T | [37] |

| Hitec | 1938 − 0.732T | 1560 − 0.001T | [34,38] |

| Hitec XL | 2240 − 0.827T | 1542.3 − 0.322T | [39] |

| LiNaKNO3 | 2088 − 0.612T | 1580 | [40] |

| LiNaKCaNO3 | 1993 − 0.700T | 1518 | [41,42] |

| LiNaKNO3NO2 | 2074 − 0.720T | 1135.3 + 0.071T | [26] |

| Chloride-based | |||

| KMgCl | 2125.1 − 0.474T | 999 | [32,43] |

| NaKMgCl | 1899.2 − 0.4253T | 1023.8 | [27] |

| NaMgCaCl | 4020.57 − 2.7697T | 12,382.2 + 0.040568T^2–42.78T | [29,30] |

| NaKZnCl | 2625.44 − 0.926T | 911.4 − 0.0227T | [32,44] |

| KMgZnCl | 2169.6 − 0.5926T | 866.4 | [27] |

| Fluoride-based | |||

| LiNaKF | 2530 − 0.73T | 976.78 + 1.0634T | [33,45] |

| NaBF | 2252.1 − 0.711T | 1506.0 | [34] |

| KBF | 2258 − 0.8026T | 1305.4 | [35] |

| KZrF | 3041.3 − 0.6453T | 1000 | [34] |

| Carbonate-based | |||

| LiNaKCO3 | 2270 − 0.434T | 1610 | [36] |

| Specific Cost $/kg | Em MJ/kg | Ev MJ/m3 | E $/MJ | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrate-based | |||||

| Solar Salt | 1.3 | 0.491 | 901.1 | 2.65 | [127] |

| Hitec | 1.93 | 0.480 | 826.9 | 4.02 | [127] |

| Hitec XL | 1.66 | 0.464 | 928.1 | 3.58 | [127] |

| LiNaKNO3 | 1.1 | 0.683 | 1285.7 | 1.61 | [56] |

| LiNaKCaNO3 | 0.7 | 0.542 | 977.1 | 1.29 | [56] |

| LiNaKNO3NO2 | N/A | 0.408 | 764.9 | N/A | - |

| Chloride-based | |||||

| KMgCl | 0.35 | 0.271 | 431.3 | 1.29 | [48] |

| NaKMgCl | 0.22 | 0.325 | 541.6 | 0.68 | [48] |

| NaMgCaCl | 0.17 | 0.289 | 739.7 | 0.57 | [128] |

| NaKZnCl | 0.8 | 0.447 | 986.6 | 1.79 | [48] |

| KMgZnCl | 1 | 0.298 | 553.4 | 3.36 | [48] |

| Fluoride-based | |||||

| LiNaKF | 2 | 0.391 | 824.1 | 5.11 | [128] |

| NaBF | 4.88 | 0.474 | 885.4 | 10.29 | [129] |

| KBF | 3.68 | 0.313 | 833.3 | 11.75 | [129] |

| KZrF | 4.85 | 0.280 | 750.3 | 17.32 | [129] |

| Carbonate-based | |||||

| LiNaKCO3 | 2.02 | 0.448 | 9912 | 4.15 | [18] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caraballo, A.; Galán-Casado, S.; Caballero, Á.; Serena, S. Molten Salts for Sensible Thermal Energy Storage: A Review and an Energy Performance Analysis. Energies 2021, 14, 1197. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14041197

Caraballo A, Galán-Casado S, Caballero Á, Serena S. Molten Salts for Sensible Thermal Energy Storage: A Review and an Energy Performance Analysis. Energies. 2021; 14(4):1197. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14041197

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaraballo, Adrián, Santos Galán-Casado, Ángel Caballero, and Sara Serena. 2021. "Molten Salts for Sensible Thermal Energy Storage: A Review and an Energy Performance Analysis" Energies 14, no. 4: 1197. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14041197

APA StyleCaraballo, A., Galán-Casado, S., Caballero, Á., & Serena, S. (2021). Molten Salts for Sensible Thermal Energy Storage: A Review and an Energy Performance Analysis. Energies, 14(4), 1197. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14041197