1. Introduction

The European Union’s new strategy for climate and energy policy expressed in the European Green Deal is heading to transform the EU into a just and prosperous society within a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy, reaching zero net greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and decoupling economic growth from the use of natural resources [

1]. On this basis, the European Commission took efforts, notably in legislative terms, to adapt the EU’s climate, energy, transport and fiscal policies to meet the objective of reducing net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. Activities at the EU level were not neutral on the strategies adopted by individual Member States, including Poland. According to the fundamental document here—Energy Policy of Poland until 2040 (EPP2040) [

2]—until 2040 more than half of installed capacity will come from zero-emission sources. A special role in this process is given to the implementation of offshore wind energy in the Polish energy system and launching a nuclear power plant. It also assumes an increased share of renewable energy sources (later as RES) in all sectors and technologies. In 2030 the RES’s share in gross final energy consumption will be at least 23%, of which not less than 32% will be in the power generation sector (mainly wind energy and solar energy). This will be the result of a significant increase of installed capacity in photovoltaics to approx. 5–7 GW in 2030 and approx. 10–16 GW in 2040. The increase in the share of RES will translate into a reduction of the use of coal in the economy. It is expected that in 2030 the share of coal in electricity generation will not exceed 56%. Unfortunately, today’s geopolitical situation relating to neutralizing negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in the world economy [

3], effects of economic sanctions imposed on Russia and the response of Russian decision-makers concerning the exports of Russian fossil fuels (especially natural gas) [

4,

5] and reports of another pandemic associated with the monkeypox virus [

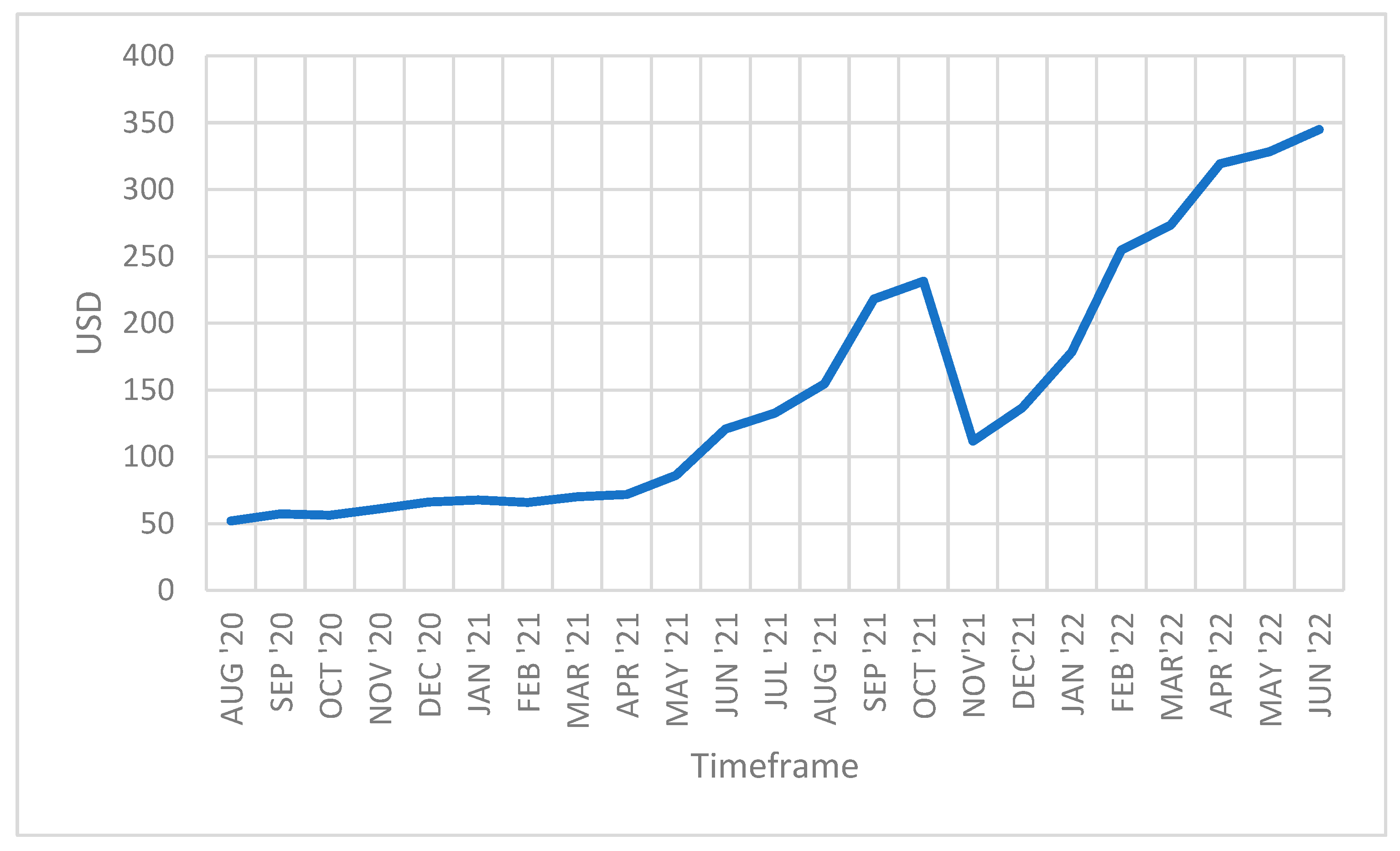

6] has an adverse effect on the situation in the energy market. It is especially noticeable after the rise of prices of energy sources, including coal, as presented in

Figure 1.

Nevertheless, an increase in the value of this energy source is not the only thing that undermines energy security of individual countries, especially members of the European Union. Given that coal is a basic source of power generation in Poland, electricity producers must obtain EU Carbon Permits in a traditional way and their value is systematically growing, as seen in

Figure 2.

In the Polish reality electricity is generated mainly from carbon-intensive sources, as presented in

Figure 3.

These changes on the markets of prices of fossil fuels and CO

2 emission permits have automatically led to rising prices of electricity itself sold to end consumers, with record highs shown in

Figure 4In April 2022 in Poland 11,083 GWh of electricity was generated in main activity producer power plants based on hard coal and lignite, which amounts to 75% of total electricity generation in this month. In comparison with 2021 data, hard coal and lignite accounted for the generation of 79.73% of the total electricity [

7].

These circumstances imply the need to promptly align previously adopted long-term strategies for transformations on the energy market to maximise national energy security by greater diversification and energy self-reliance [

8]. In today’s geopolitical and economic conditions, optimisation of current plans focuses mainly on the protection of end consumers against excessive increases in energy prices and progressing energy poverty. This is to be made possible by building “energy sovereignty” and a gradual independence of the national economy from imported fossil fuels. As a result, one of the consequences of intensification of efforts to achieve this goal is the diversification of the energy mix. Therefore, in has been assumed in the Polish realities that by 2040 approximately half of electricity generation will come from renewable energy sources. According to 2021 data [

7] RES accounted for only 10.94% of the energy generated, with the result of 18,984 GWh. In turn, the national electricity consumption in 2021 was 174,402 GWh. However, EPP2040 declares reaching at least a 23% share of RES in gross final energy consumption in 2030. The objectives laid down by Polish decision-makers do translate into results of an increase of energy generated from RES, which is shown in

Figure 5.

Rooting the new strategies of diversification of the energy mix in locally available energy sources will be an alternative to the now-centralised power supply. However, the development of distributed power generation and building state energy security on it will have to ensure guarantees and stability of supply in the national electricity system. Materialization of these forecasts will be possible through investment and development of technology allowing the use of RES independently from atmospheric conditions and storage, which involves obtaining relevant financial support. The law of the European Union, by Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council (UE) 2018/2001 of 11 December 2018 on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources (Official Journal of the European Union of 21.12.2018, L 328/82 later as RED II or directive), to support the achievement of the common goal of the share of energy from renewable sources at the level of 32%, provides a few measures that Member States may employ. Recital 16 of this Directive says that financial support is a key element of increasing the market integration of renewable electricity, while taking into account the different capabilities of small and large producers to respond to market signals. There is no doubt that at the local level it is indeed the small installations that ensure roll-outs of renewable energy-related projects. Thus, ensuring a positive cost-benefit ratio at the current stage of development of generation of electricity from renewable sources requires application of special instruments that support their operation that should strive to minimise general integration costs, in line with the path to lower emissions while at the same time achieving the low-emission objective for 2050. Given the current impact of support mechanisms engaged by Member States, including Poland, it must be added that they were an effective measure promoting renewable energy. As a result, these instruments will still play a key role in the EU goal of climate-neutrality [

9] (p. 91). Given that each Member State has a different potential in generating energy from RES, relevant measures of a broadly understood promotion of the use of energy from RES are adjusted to the needs of achieving the desired level of renewable energy generation on the one hand, especially by means of EU law, and required rules for state support on the other. Pursuant to Article 2(5) REDII, the “support scheme” means any instrument, scheme or mechanism applied by a Member State, or a group of Member States, that promotes the use of renewable energy by reducing the cost of that energy, increasing the price at which it can be sold, or increasing, by means of a renewable energy obligation or otherwise, the volume of such energy purchased. RED II lists the following examples of measures to support electricity generation:

investment support,

tax exemptions or reductions,

tax refunds,

renewable energy obligation support schemes (e.g., green certificates),

direct price support schemes [e.g., feed-in tariffs and feed-in premiums].

In this light, the EU introduces the freedom of choice of support measures that are best suited to national determinants instead of an obligatory, single and common support scheme applied throughout the entire Union (pp. 38–45, [

10]). Lack of centralised support measures allows Member States to develop optimal national mechanisms that allow maximum achievement of national goals set by the EU law. Therefore, it does not strive to harmonise them, though Member States are encouraged to adopt a common model of promoting energy from renewable sources. [

9,

11] (p. 174). This is why Member States apply various support models which are classified as direct measures (e.g., feed-in tariffs) or indirect measures (e.g., tax reductions) (pp. 287–288, [

12]). At the same time, direct support measures are the most important for the dynamic development of the RES sector [

13]. Nevertheless, direct and indirect measures are not mutually exclusive; rather than that, they complement and support each other. For instance, thanks to investment subsidies (direct measure) it is possible to subsidise the building of an installation for renewable energy generation and guaranteeing a stable price for each kWh of electricity from RES installations allows for a relation between costs and benefits from renewable energy production to be determined. The Polish legal system regulates the following forms of supporting generation of energy from RES in the Renewable Energy Sources Law of 20 February 2015 (consolidated text, Dz. U. (Journal of Laws) of 2021 item 610 as amended, hereinafter RESL):

Certificates of origin for renewable energy (Article 44), which must be obtained by an energy company, end consumer, industrial consumer and brokerage house (Article 51) and then submitted to the President of the Energy Regulatory Office or else a substitution charge must be paid (Article 56);

Net-metering (Article 44(13) and (14)—a producer of renewable energy in a micro-installation who is a business may execute a power purchase agreement with the obliged supplier under which settlement between the amount of electricity taken from the grid and the amount of energy fed to the grid is done in a given half a year. The settlement is done on the basis of actual meter readings.

Discount system—for producers who are prosumers of renewable energy, whose micro-installation was connected to the power distribution grid upon a request filed with the distribution system operator no later than on 31 March 2022 or where the electricity produced by them was fed to the power distribution grid for the first time before 31 March 2022, the settlement with the obliged supplier of the amount of electricity fed to the distribution grid corrected by the amount of electricity taken from this grid for the prosumer’s individual needs who generates electricity in micro-installations with total installed capacity: (1) more than 10 kW—in the 1 to 0.7 quantity ratio; (2) not more than 10 kW in a 1 to 0.8 quantity ratio. This system for this category of prosumers will stay in force for another 15 years (Article 4(1)).

Net-billing—for renewable energy producers in micro-installations in which electricity was generated and fed to the power distribution grid for the first time after 1 April 2020. The obliged supplier bills the value of electricity fed to the power distribution grip from 1 July 2022 by a renewable energy prosumer, collective renewable energy prosumer or a renewable energy virtual prosumer who generated electricity in a renewable energy source installation which was connected to the grid and from which electricity was fed to the power distribution grid for the first time after 31 March 2022, which is set for each calendar month and is a product of the total electricity fed to the power distribution grid by the prosumer and the monthly electricity market price. A prosumer is given a dedicated billing account where the amount and value of electricity is recorded (Article 4(1a)(2); Article 4b; Article 4c).

Fixed price (Feed-in-Tariffs/Feed-in-Premium)—dedicated only for purchase agreements for electricity that is not consumed but fed to the grid by a renewable energy producer in a RES installation with the total installed capacity less than 500 kW, at a purchase price that is 95% or 90% of the reference price, depending on the type of an RES installation (Article 70a and 70e);

The auctioning system—means that a purchase agreement must be signed between a renewable energy generator in small-scale installations with total installed capacity less than 500 kW and a relevant obliged supplier within one month or six months from the date the session is closed (Article 82).

However, regardless of the support measures applied in individual countries, European electricity markets (following the American system) have produced a non-public instrument, that is a power purchase agreement (later PPA or PPAs). By default, it is a market instrument that allows electricity producers to have a stable income, thus secured supply of energy from RES to consumers at competitive prices in a long-term perspective, which is generally not provided by the public support system. The PPA must be viewed as a system that supports or complements currently applied measures to promote electricity generation because such financing of renewable energy is becoming more and more popular, especially among buyers who are businesses (it is then referred to as cPPA -corporate PPA). The year 2021 alone saw record volumes of renewable electricity contracted through PPAs in Europe—6.9 GW [

14] (p. 31). ICT and heavy industry have contracted 61% of energy capacity through corporate PPAs in Europe [

14] (p. 33). It must be also highlighted that PPAs are crucial in assessing the “bankability” of investments in renewable energy, which translates into increased opportunity for funding from banking institutions which will treat borrowers as solvent and capable of guaranteeing timely and full payment of the financial support. There is no doubt that financing renewable energy production ensures stability and certainty of sources for paying off the funding and real assessment of financial risks. Despite the PPA’s significance for the development of renewable energy production (best seen in the Danish, Finnish, British and Norwegian markets), legislative acts do not use a legal definition of this term. Certain normative anchoring can be seen in the said RED II directive. Pursuant to Article 2(17), PPA may be classified as an agreement for the purchase of renewable energy under which a natural or legal person agrees to buy renewable energy directly from the power producer. It is worth adding that RED II assumes that Member States will assess the regulatory and administrative barriers for long-term power purchase agreements and will then remove unjustified barriers and will help popularise such agreements. Apart from that, Member States were guided to facilitate popularisation of renewables power purchase agreements in their integrated national plans of energy and climate, and most of all to ensure that these agreements are not subject to disproportionate or discriminatory procedures and charges. The PPA, as a completion of public support schemes, is mentioned directly in RED II in Article 19(2c) as a source for issuing guarantees of origin and also in Article 21(2A) as one of the premises for self-consumers’ selling their excess production of renewable electricity.

Given this economic, political and legal context at the EU level, sequential research questions need to posed/asked to verify the correctness of the research hypothesis therein which says that in the light of Polish legal regulations, the competence of energy market participants to conclude a PPA will not be a key instrument of development of renewable energy production at the local level, as it is not a sufficient alternative to the current public forms of supporting generation of energy from RES:

What is the legal classification of legal relationship under a PPA in the Polish legal system?

Will the PPA be an alternative to the current scheme for supporting renewable energy production?

If the answer for question no. 2 is no, is it legitimate de lege ferenda to amend Polish regulations on signing and performing PPAs by participants of trading in renewable electricity?

2. Materials and Methods

The analysis to determine the significance of the “Power Purchase Agreement” for the development of local energy markets in the context of Polish legal conditions is theoretical. All statistics presented in figures are purely for reporting purposes and are not based on results of empirical research. The main objective of these figures is to illustrate the economic trend on the national and global electricity markets and also to present the development of production and importance of renewable electricity in Poland. The graphic presentation of non-legal factors will allow a better display of what is to be the most important aspects that are decisive in taking up a discussion on PPAs in Poland. This visualisation, together with a general outline of legal aspects of promoting renewable energy production, will also allow a more transparent introduction to a more detailed discussion on the status of the Polish legislation and its usefulness in the development of distributed power generation at the local level.

This research was based on methods applied in the legal science, which is part of social studies. Out of the research methods applied in the Polish legal scholarship [

15], that is: 1. the dogmatic approach—examination of the law as it is given, 2. the historical approach—examination of the development of a law throughout history and 3. the comparative approach—legal comparison, the dogmatic research approach (the analysis of the law in force) was chosen due to the subject matter taken up in this study. There are three reasons behind this choice. First of all, it focuses on investigating the law that is effective now. To this end, this methodology allows the use of research methods such as analysis and interpretation of regulations to determine the content of the law in the investigated scope, terms that law uses and also applicable instruments present in this law and likely to feature in it in future. Secondly, this method means that while investigating currently binding regulations it is possible to take into account views expressed by legal scholars and commentators and in judicial decisions and it is also possible to refer to a non-legal context in order to determine the goals that the legal norms are to serve. Thus, the use of a graphical representation of statistical data is not only necessary, but also justified in this light. Thirdly, by using this method it is also possible to assess the current legal status (de lege lata conclusions) and propose changes to this regulation in future (de lege ferenda conclusions) by means of said research tools. The derivative concept of legal interpretation created by prof. Maciej Zieliński [

16] is used here to interpret laws and to create legal norms on their basis. This concept is expressed in the Latin maxim “omnia sunt interpretanda”. This process starts from a legal interpretation which is intended to specify the meaning of phrases used in a legal text by means of legal provisions. In this concept it is especially important to differentiate between a provision of the law understood as an independent editorial unit of a legal text that takes the form of a sentence in the grammatical sense and a legal norm that is the result of a process of interpretation of a legal text, which determines the addressee’s behaviour in a specific way in certain circumstances. If the result of a linguistic interpretation still causes doubts, then a systemic interpretation is applied and the functional interpretation as a last resort to reach a clear and unequivocal legal norm (both in the aspect of its content, scope of regulation and application). This results from the fact that texts of legal acts are drawn up at the descriptive level and read at the normative level (the addressee, circumstances, imperative/prohibition of a given behaviour), which by default causes imprecision due to ambiguity of the language in which the text of a legislative act is drawn up [

17] (p. 97).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physical PPAs and Virtual PPAs as Basic Types of PPAs

As has already been presented, production of electricity from renewable sources is becoming an ever greater alternative in relation to electricity generated from fossil fuels, both in the financial aspect and in the aspect of carrying out international and national strategies for a change away from the mechanism of production of electricity from carbon-intensive sources to low- or zero-emission sources. However, state (public) schemes for supporting renewable energy production do not ensure that producers reach constant and stable incomes in the long run and sources of additional income which guarantee that RES-related projects may obtain external funding, which translates into increased “bankability” of investment related to the building and use of technology for renewable energy production. In this light, PPAs gain importance for participants of the market of production and trading in electricity [

18,

19,

20]. PPAs are, however, an instrument free from any risk concerning the balancing of the price of energy and the related guarantee of production and transmission of the contracted energy. The literature presents many models diagnosing the said risk and presenting mutually exclusive solutions or such that significantly minimise potential errors in how much electricity is purchased and supplied under PPAs [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. There is no doubt that contractual specification of the volume of the electricity produced, its costs and time limits of cooperation between a producer and a buyer allows minimisation and securing of interests of parties against fluctuations of market process, which undoubtedly stabilises long-term energy supplies. It is also pointed out that PPA optimisation relating to a risk reduction strategy is possible thanks to a combination of many renewable energy locations and technologies (PPA portfolio) [

20,

26].

Given that the basic function of PPA is to secure prices at the level that allows guaranteed profits for producers of electricity from RES and affordable green energy for its recipients in a long-term perspective, it must be noted that there are many different kinds of PPAs depending on the structure of the energy market in a given country and its regulations [

19] (p. 14). The literature gives a lot of focus to models of mutual settlements intended to mitigate uncertainty as to prices or amount of electricity supplied, to offer a structure that is beneficial to both parties (reliability of energy for the buyer and financial attractiveness for the producer) [

20,

27,

28,

29].

Being guided by a basic criterion of capability of a renewable energy producer to physically deliver a specific volume of electricity, it may be identified the following [

19,

30] (p. 4, 14):

Under pPPAs, buyers who enter into a long-term contract with a renewable energy producer for a physical delivery of part or all energy produced by him are connected with one another by joint infrastructure. This is why at least the following types of contracts can be named, which differ in how electricity is supplied:

on-site, where the two entities are neighbours and thus direct access to electricity produced is possible;

off-site or sleeved, which assume that a renewable energy producer and its buyer are not connected by technical infrastructure and use the grid (access to the grid) and services (managing energy take-up and balancing) of third parties (it will usually be electricity suppliers or energy traders).

On the other hand, vPPAs are contracts for difference or swaps which are not associated with physical delivery of electricity or the producer’s and buyer’s. The buyer pays the producer a fixed price for each MWh of energy produced, for which he receives a floating price, which allows clearing of one another’s accounts and also, importantly for the buyer, green energy’s guarantee of origin. The physical delivery of energy is irrelevant in this construct, which is down to the energy markets, technical structure where monopolists own distribution and transmission networks. Their basic goal is to provide financial security against changes in energy prices (market risk hedging). Because they do not concern physical energy delivery, they do not generate dispatch costs and load points limitations. Therefore, it is possible to illustrate this contractual construction so that the renewable energy producer sells it at the spot market on which the buyer meets his needs within the agreed production volume. Performance of vPPAs, however, means that the renewable energy producer compensates the excess price on the spot market to the buyer if the price was higher than agreed in the PPA. On the other hand, the buyer compensated the producer for the difference if the price on the spot market is lower than agreed in the vPPAs.

3.2. Qualification of Physical PPAs and Virtual PPAs according to Polish Regulations

When confronting the international literature and practice described above with Polish experience it must to be pointed out that it is quite modest and at a very early stage of development, as seen in few, though emerging studies [

30,

31,

32]. Therefore, when assessing the Polish legal system, one must come to the conclusion that there is no regulation that directly refers to PPAs. However, taking into account the definition from RED II and confronting it with two basic types of PPAs, it needs to be recognised that it applies mainly to pPPAs which take the form of contracts of sale. In turn, vPPAs must be qualified as financial instruments which may take the form of swap, options or forward contracts. Constitutional differences between pPPAs and vPPAs cause far-reaching regulatory differentiation both on the Polish and European scale. Starting from the most fundamental issue, only pPPAs will fit under broadly understood contracts for purchasing and transferring electricity which will involve acquisition of legal titles to electricity. In this light they will fit the structure of the conventional trading in electricity where the supply (physical delivery) of electricity is done through a power infrastructure, that is a direct line or distribution and transmission network. In the perspective of the Polish regulation, such pPPAs will fit under a contract of sale of electricity regulated in Article 535 in connection with Article 555 of the Act of 23 April 1964 Civil Code (consolidated text, Dz. U. (Journal of Laws) of 2020 item 1740 as amended, hereinafter CC and the Energy Law of 10 April 1997 (consolidated text, Dz. U. (Journal of Laws) of 2021 item 716, as amended, hereinafter EL). [

33], and for questions that deviate from the typical model of sale of electricity the parties will act under the competence resulting from freedom of contract under Article 353

1 CC [

34]. However, a problem that occurs here due to different variants of pPPAs (on-site; off-site; sleeved) is the possibility of a direct connection of the renewable energy producer with a buyer. Pursuant to Article 7a EL, the building of such a network entails an additional legal and investment risk [

30] (p. 57). It requires a prior consent of the President of the Energy Regulatory Office, and such installations must meet requirements laid down in separate laws, in particular: construction laws, electric shock protection laws, fire protection laws, laws on the compliance system and in regulations concerning the technology of producing gaseous fuels or energy and type of the fuel used. Therefore, this involves barriers that may prevent such contractual relations from being made or that may make this type of pPPAs not profitable for the parties. If the production of energy from RES is located in the direct neighbourhood of the buyer, there will be a problematic issue of ownership of equipment and installations that allow delivery of electricity and the resulting legal implication if they are used against a charge. Running a gainful activity for the transportation of energy and use of necessary equipment and installations means that such an activity will be qualified as distribution, which requires the operator to obtain a licence and a status of a distribution network operator. To avoid such legal problems, distribution networks should be the property of the recipient (which may increase investment costs of singing a pPPA, as suitable networks must be built and then maintained) or of the producer, who may transfer the costs of using this network onto the buyer, which in the long-run may lower the income so much that it becomes unprofitable. An alternative solution is to execute a suitable distribution service contract with an entity who deals with it professionally, which releases the parties from the obligation to oversee the distribution network and all regulatory issues, though at the cost of paying distribution fees to the operator. In this light, the most convenient solution for the parties where services of a third party (distribution network operator) are involved does not encourage renewable energy production at the local level [

30] (p. 58). An additional problem that may emerge on the side of the recipient and the producer is the problem of meeting the total demand for electricity, if the producer’s capacity is lower than the recipient’s demand or the use of the entire electricity generated by the producer if the recipient does not have such great demand. This means that consideration should be given to the participation in these relations of a third party, a trading company, which will be able to use the excess energy produced or to supplement its shortages. To avoid a situation where the renewable energy producer assumes the role of a trading company, which requires a relevant licence, the Polish literature offers the possibility to execute a trilateral agreement [

30] (p. 58). Having to resort in the end to such an option, which corresponds to the current Polish specific characteristics of the energy markets, undermines the sense of using classically understood pPPAs by renewable energy producers (e.g., energy clusters or energy cooperatives). As a result, overall, it is a transaction that is unprofitable for them and that carries a great legal risk that involves the obligation of complying with energy regulations that impose the obligation to have suitable permits or licences if their activity goes beyond the status of renewable energy production (e.g., in the period when there is no appropriate weather—no suitable sunlight or wind, the producer will buy biomass or biogas to meet the recipient’s needs).

Moving on to the second option of PPAs that involves only financial settlements between producers and the recipient it should be noted that this contractual construction goes beyond the said definition from RED II. It does not rule out qualifying it as another way to promote renewable energy production, however, contrary to pPPAs that are subject to completely different regulations that are not related to the energy market. In the Polish legal system vPPAs must be treated as a financial instrument which corresponds to Article 2(1)(2) of the Act of 29 July 2005 on trading in financial instrument (consolidated text, Dz. U. (Journal of Laws) of 2022 item 861 as amended, hereinafter ATFI) and as one of the types of financial instruments (swap, options, forward) defined in Section C of Annex 1 to the Directive 2014/65/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on markets in financial instruments and amending Directive 2002/92/EC and Directive 2011/61/EU, hereinafter as MIFID II. First it needs to be noted that trading in financial instruments is regulated in Article 69(1) and (2) ATFI. However, pursuant to Article 70(1) ATFI, the legislator introduced exceptions that allow free trading (acquisition and transfer on one’s own account) in financial instruments that fall under them. However, pursuant to Article 70(1)(4), it will only involve vPPAs which may be qualified as a financial instrument other than commodity derivatives. Unfortunately, in the light of Article 2(1)(2)(d-f) and (i) ATFI, vPPAs structures such as swap, options and forward financially settled, for which energy produced from RES was a base instrument, will be classified to the category of commodity derivatives. Pursuant to Article 70(1)(10) ATFI they will be possible as exclusion for an additional activity. However, this will involve having to meet requirements laid down in subsection 1(10), which, similar to a pPPA, creates an administrative barrier that may effectively discourage entities interested in a vPPA from signing it. It is pointed out that freedom in signing vPPAs will be possible if it is given the form of a financial instrument called CfD [

32] (p. 22).

3.3. Physical PPAs and the Polish Support Scheme for Renewable Energy Production

In the Polish energy law, as was outlined in the introduction, there is a number of measures to support energy from RES. However, taking into account the main criterion of being able to use public support measures such as feeding the energy produced directly to the distribution and transmission network, we must note that using pPPAs in the Polish reality is an alternative that does not correspond to needs of producers who mainly want or have to base their activity on a public support scheme. If energy is not supplied by means of distribution and transmission networks, then one cannot engage public support measures that guarantee a certain income, or at least a permanent outlet for the produced energy. Only the feeding of the entire or part of the amount of the energy produced gives the producer a basis to benefit from public aid under the right to cover the negative balance and the guarantee of the obliged entity to purchase electricity. Therefore, in this light, the integration of PPAs by an electricity producer involves legal and economic limitations. It must be pointed out that in the light of Article 42(1) and (2) RESL, the precondition for the obliged buyer to purchase electricity is the offer of selling the total electricity from renewable energy sources in an RES installation produced and fed to the transmission or distribution network within at least 90 consecutive days. Furthermore, this obligation arises from the first day of feeding this energy to the distribution or transmission grid and lasts for the next 15 years, no longer than to 30 June 2039; this period is counted from the date of producing electricity from renewable energy sources for the first time, confirmed by a certificate of origin. On the other hand, when it comes to the auctioning system, we must point to the fact that the obliged supplier buys electricity produced in an RES installation with installed capacity less than 500 kW, fed into the grid and sold, from the producer of this energy who, i.a., won the auction at an adjusted price only in the amount not greater than specified by the given producer in the offer submitted by him. With this as a basis, smaller renewable energy producers many be not interested in searching for a partner to sing a pPPA. On the other hand, producers of electricity from RES in other installations may not have an interest in executing pPPAs if there is an operator (obliged supplier) on the market. This is the entity which will be obliged to cover the difference between the value of the energy sold at an average daily price of electricity and the value of this energy determined on the basis of the price from the producer’s offer, if, naturally, he wins the bid. Therefore, it may be assumed that renewable energy producers at the local level will be more willing to apply for public support for the energy produced by them rather than to create pPPA-related relationships with other counter-parties.

4. Conclusions

The analysis of the PPA subject matter in the light of the Polish energy law and regulations on renewable sources of energy proves that in present economic, political and legal circumstances, Poland’s current legal conditions do not provide a legal instrument of development of renewable energy production, even more so an instrument that should support its production at the local level, despite the fact that participants in the energy market may be using PPAs. Even though existing regulations do not in fact rule out creation of such contractual relations between the producer and the buyer, when we look at the distribution of mutual rights and obligations, especially in how which this obligation is carried out, then it turns out that legal or economic barriers will turn this construction into a model that is difficult to accept. This is best seen in PPAs that are based on physical power delivery. The obligations that currently are associated with the possibility of laying a direct line between a producer and a buyer mean that only off-site pPPAs may be used in the Polish legal system. However, having to take into account third parties in them, such as distribution system operators or energy trading companies, will not make these contractual rations significantly different from those that are already in operation on the energy market (such as for example: comprehensive agreements, the sale of energy, or distribution service agreements). Moreover, in the light of public support schemes, entering into such contracts with these entities does not rule out their use, which sometimes will be impossible with pPPAs. As a result, it is key to relax the possibility to create a direct line next to public transmission and distribution networks, and then to relax the requirements towards parties of on-site pPPAs for concession obligations if the transport of energy is to be made against payment. The existing regulations are not an encouraging environment for the development of PPAs based on physical delivery of electricity, mainly because the generated electricity must be fed to the distribution or transmission network. This is why they are not an alternative to numerous measures of public support for RES energy production, which inevitably correspond better with the Polish legal context and ensure a source of income or guarantee an outlet. In this sense, they require less effort to achieve goals that are sensitive to PPAs, especially from the perspective of smaller producers, whose market position does not allow an easy search of potential counter parties. Even if the PPAs construction were to be detached from the requirement of physical delivery of power and if we relied on the vPPAs, the answer will still remain the same in the Polish legal reality. Just like vPPAs allow security—acceptable to both parties to the agreement—when electricity prices change, still, due to the regulation of trading in financial instruments in Poland the parties will not enjoy sufficient freedom to independently enter into most obvious forms of such contracts, such as swap or options. An attempt to force the possibility to execute such contracts for difference without a regulation will still involve additional legal barriers to demonstrate operation of an additional activity, whereby executing such a contract will have to be preceded by a procedure of an uncertain result.

This analysis proves that the existing status of regulations in Poland means that pPPAs and vPPAs have limited significance and are rather dedicated to entities that will be able to face up to administrative barriers (e.g., obligation to obtain permits and licences) and legal ones (e.g., a combination of public support with a pPPA). In this approach, if the potential of on-site pPPAs cannot be used fully to the benefit of more accessible off-site pPPAs and vPPAs, it does not encourage qualification of this conventional construct as conducive to the development of renewable electricity at the local level. It must be pointed out that for off-site pPPAs, and all the more so for vPPAs, the distance of the RES energy production installation from the buyer of this energy is not really relevant. An increase of importance of distributed power generation at the local level will require further-reaching changes, not only in the legal aspect, but also a technological one. Gradual decentralization of power generation along with a transportation system will be a chance for the development of on-site pPPAs. However, one can risk a statement that until a technology is designed that will stabilise how green energy is generated and stored, which will provide more and more support rather than threaten the national energy security through predictability and stability of supplies, a practice that best encourages the development of local sources of renewable energy production, such as on-site pPPAs, will not flourish. Until then, public support schemes will be the dominant support measures for local markets of renewable energy as the most coherent with the current legal status in Poland.