Abstract

The inconsistency of arguments regarding the value of diversification strategies means that there is a lack of a unified methodological approach and a method for evaluating the impact on efficiency and competitive ability of companies. Research shows that diversification was crucially important for oil and gas companies during the economic shocks of 1998, 2009, and 2015. Nowadays, oil and gas companies apply the strategy of green diversification to solve climate change problems and adapt to energy transition trends. The goals of 14 global oil and gas companies with regard to carbon neutrality were analyzed in this study. This research expands the theoretical studies of diversification processes and outcomes in the oil and gas industry and contributes to the discussion of the feasibility of companies implementing renewable energy projects. The factors that prompt oil and gas companies to adopt green diversification were formulated, and their key strategic priorities were determined depending on the volume of proven resources. The research suggests that global shocks in the international energy market and a reduction in the significance of oil and gas resources in the overall power balance stimulate companies to diversify their asset portfolios, but such strategy does not protect against negative impacts. In addition, important issues were identified for further analysis.

1. Introduction

Diversification is a central issue in strategic planning and management. Initially, diversification was viewed as a strategy for new market and product development. However, over time, diversification has gained ever-growing relevance and has been considered as a method for achieving the maximum use of economic reserves and institutional resources and for maximizing competitive advantages. Scientific research is often conducted to study the essence of diversification, determine its motives, and evaluate the economic consequences of adopting a diversification strategy.

However, the scientific community still has not reached a consensus on the efficiency of following a diversification strategy. This is illustrated firstly by the large number of previous and new works on this topic, and secondly by the inconsistency of their conclusions. Many researchers, including Goold and Luchs [1], Amihud and Lev [2], Wang [3], and Stein [4], hold the opinion that a successfully implemented diversification strategy has economic potential. However, other scientists, including Palich et al. [5], Denis et al. [6], Berger and Ofek [7], and Rajan et al. [8], point to the limited evidential basis for diversification efficiency, leading to its investment, organizational, and management potential not being assessed. The main problem with inconsistency in terms of diversification is that the evidence previously obtained in support of a certain view will be compromised in the future.

Thereby, the limited research devoted to the implementation of diversification strategies in the oil and gas sector can be noted. In order to expand the theoretical basis for the topic, in this study we reviewed specific features and areas of diversification for oil and gas companies, and green diversification in particular, which suggests searching opportunities in all sectors of the energy market (wind, solar energy, biofuels, green hydrogen, etc.).

The progress of the global economy toward net zero and the rapid growth of the renewable energy sector determine a significant shift in the strategic priorities of the key players in the energy market [9]. International oil and gas companies will likely not ignore opportunities for growth in the field of renewable energy sources. Green diversification is considered an opportunity to preserve sustainability and enhance reputation in the global market [10]. It is also a way to assure investors that companies can be reliably insured against price reductions for energy sources, market volatility and inefficient capital management, climate-related risks, and discouraging forecasts regarding the long-term demand for energy sources [11,12].

Today, it is difficult to evaluate whether the stated objectives of the oil and gas companies in the field of clean market segments will be implemented. It will require significant investment, technology, competency, and changes in organization and culture to achieve new strategic perspectives. Moreover, as Cherepovitsyna et al. note in their research, there is no certainty that all measures announced by companies will actually be implemented and not turn out to be merely a declaration [13].

The study covers a long period in the energy market, from 1995 to 2022. This allowed us to track changes in the strategic priorities of oil and gas companies in retrospect, and to identify key differences in and prerequisites for green diversification. Considering the transition to low-carbon energy, in this study we propose the differentiation of oil and gas companies by their level of reserves in order to determine possible directions for strategic development. Specifically, based on a detailed analysis of the strategies of 14 oil and gas companies, the key principles of strategic development in the context of decarbonization and development of renewable energy projects in the asset portfolio are formulated, which will help companies meet the challenges of energy transition.

This study was aimed at discovering the conceptual features of diversification strategies, determining the perspectives of oil and gas companies’ implementation of green diversification, and revealing areas for further studies.

The research is organized as follows: Section 3.1 analyzes and systematizes the main scientific ideas around the diversification phenomenon. Section 3.2 reveals the main areas of diversification of oil and gas companies in periods of economic crisis. Section 4 presents profiles of green diversification in oil and gas companies. The conclusion outlines the main findings of the study and prospective research issues.

2. Materials and Methods

The study is mostly analytical, and qualitative methods of analysis were used to expand the theoretical knowledge in the area of diversification. Using content analysis along with critical and comparative analysis, we conducted a comprehensive study of diversification strategies, systematizing the main ideas on this topic regarding pros and cons.

In order to study the issue of diversification of oil and gas companies, a retrospective analysis of oil pricing from 1995 to 2022 was carried out, which revealed the directions of diversification during periods of price decline. The results made it possible to create research questions, identify the criteria for research, and generalize at the level of the entire study.

To clarify the issues of green diversification of oil and gas companies, we selected the largest market players based on their contribution to world production. A detailed analysis of the corporate reports of these companies made it possible to determine their key prerequisites and strategic priorities.

The proposed conceptual approach to the green diversification of oil and gas companies as a way to adapt to the new energy system prompts new research questions and prospects for further research.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Conceptual Approaches to the Phenomenon of Diversification: Pros and Cons

The researchers’ interest was drawn to increased diversification of companies that occurred in the 1950s and 1960s, when the experience of several multi-specialty companies proved that any level of diversification was possible and could result in success [1]. At that time, many large companies found that they had depleted their internal sources of economic growth. Expanding production, implementing new business services and areas, and entering new markets seemed to be a reasonable and efficient strategy. As Thompson and Strickland [14] mention, it is dangerous to put all of one’s eggs in one basket: when the industry’s appeal is reduced, it is difficult for companies to maintain production and profits at a high level.

Later, in the 1980s, many companies that had multiple business areas started setting another goal for themselves—to find a compromise between growth and the maturity they had already achieved. Backward movement, from diversification to specialization, took place. Strengthening the core business based on key competencies became the priority again. The tendency of abandoning diversification slowed down in the 1990s. Nowadays, multi-specialty companies still hold high competitive positions, and many companies choose diversification as their main form of business.

Over the years, discussions have not ceased regarding the essence and feasibility of diversification. A substantial number of researchers around the world have attempted to justify its theoretical and empirical bases. However, the diversification concept still has quite heterogeneous and non-universal interpretations, which makes applying it rather difficult.

From the moment of its introduction, the meaning of the term “diversification” has continuously become more complicated and detailed. The earlier approaches considered it to be an increase in the number of markets [15], business fields [16], or areas [17] in which a company operates. That is, it includes the redistribution of the company’s resources to other business areas that differ significantly from the existing ones [18,19]. Two main ways to implement a diversification strategy have been determined: by a process of internal business development or by external expansion [20].

There are two key types of diversification strategies, based on an assessment of the relationships between business segments [21,22,23]:

- Related diversification, which is applied based on the main type of business or product. It involves the assimilation of new products related to the core business activity by processes or consumers and/or new segments of consumers or geographical markets.

- Unrelated (conglomerate) diversification, which involves starting an activity that is not related to the core business in terms of organization, production, or processes.

When considering the concept of diversification, many authors initially focus on the main profiles and dominating features. However, upon deeper consideration, a close relationship is found between diversification and other aspects of a company’s business. Research areas and theoretical prospects have gradually expanded, attracting scientists specializing in different disciplines (financial science, strategical management, organizational theory, marketing) to the analysis of diversification [24]. Diversification has gained a broader meaning; in addition to entering into new business fields and areas, it also involves the efficiency of capital distribution, adaptability to turbulent external conditions, improved reputation in the market, and the assurance of long-term sustainability.

Choosing a diversification strategy is an important management decision [2,25]. The reasoning behind the choice is based on the intention to reduce or distribute risk and to leave stagnant markets and gain a financial benefit from working in new areas. The objective of the strategy is to enhance competitive ability and stabilize cash flow, thus maximizing company value. Therefore, the researchers share the opinion that diversification is a difficult task, one that requires organizational and process changes as well as new management policies. Companies should reveal new market opportunities in the fast-moving macro-environment and respond to them promptly, making bold decisions. The reasonable decision to diversify should be made based on current expectations and forecasts for the future.

However, a number of authors question the advisability of choosing to diversify. They argue that concentrating on the core business has several significant managerial and organizational advantages, while expanding the business by creating non-core areas often turns out to be risky and inefficient. According to an assessment by Lynch and Rothchild [26], companies that choose diversification are often focused on the product, which is, first, overestimated, and second, beyond the scope of their competencies and resources, which results in maximum losses. Peters and Waterman believe that true success can only be achieved by a business that is understood clearly [27].

The key to determining the advantages of diversification is the rational distribution of financial resources, implemented mainly by developing the internal capital market. The internal capital market is a mechanism of movement of cash flow generated within a diversified company from one business segment to another [3,28]. Matsusaka and Panda argue that an efficient internal capital market results in an optimal redistribution of financial resources due to lower transaction costs as compared to external capital markets [29]; Stein believes that it improves the standards for screening investment projects [4]; and Henderson assumes that it protects businesses against rapid changes in investor sentiment in the market [30].

Hauschild and Knyphausen-Aufseß analyzed another rational explanation for taking advantage of diversification related to the possibility of achieving economies of scale by using resources simultaneously [31]. Redistributing resources and opportunities among business units helps the company obtain additional profit and develop a portfolio of enterprises that mutually strengthen one another.

Bernheim and Whinston analyzed a theory of market power and the methods by which multi-specialty players can obtain power anti-competitively [32]. Thus, for example, diversified companies can use the profit obtained in one area to reduce prices in another area (cross-subsidization). In addition, large players can make deals to force out small competitors. Such measures will maximize the company’s value due to the growth of market power and increase future profits, despite the fact that pricing might fall below the level of expenditures.

Some researchers have noted the advantage of combining multiple types of diversification. Based on the examples of transnational companies, Chkir and Cosset [33] showed that the combination of international and product diversification reduced the risk of default. Garrido-Prada et al. concluded that combination of product and geographic diversification would improve company performance during economic crises [34]. Qian et al. examined regional diversification, which has an advantage compared to global diversification [35].

Neffke and Henning [36] and Tate and Yang [37] focused on the higher human potential (skills, competencies, creative thinking) in diversified companies, where cross-exchange of experience and integration of knowledge are the strongest competitive advantages. This aspect is of the greatest interest to enterprises in high-tech fields, which require a constant search for innovation [38].

The works devoted to the analysis of diversification efficiency during economic shocks deserve special attention. Their results are especially relevant under present-day conditions, when the global economy is facing unprecedented shocks [39]. Kuppuswamy and Villalonga reasoned that, during periods of unstable external market condition, investors show higher interest in diversified portfolios, which appear less risky and can fulfill the insurance function [40]. Matvos and Seru [41] noted that the internal capital markets can compensate for disproportions in the financial market during periods of turbulence. Volkov and Smith [42] confirmed that internal capital market efficiency is enhanced during highly unstable periods, and emphasized that the firm’s value increase during recession is temporary. Aivazian et al. [43] added coinsurance of cash flows and higher forecasting accuracy to the factors contributing to the continued sustainability of diversified companies.

There are hypotheses to the contrary, which challenge the idea of efficiency and enhanced competitive ability through diversification. Grant et al. provide evidence for the limited use of the advantages of diversification [44]. The curvilinearity theory states that a high level of diversification results in reduced profitability and productivity after a certain point [5].

Opponents of the concept of an efficient internal capital market claim that separating management from property and delegating managerial duties in diversified companies result in informational asymmetry and an agency problem. Jensen and Meckling [45] and Denis et al. [6] argued that agency theory is based on the assumption that conflict of interest between shareholders and managers is inevitable due to the latter’s intention to maximize their personal benefit. Managers go along with the diversification strategy even if it is not efficient, since diversification allows them to reduce the risks of the business areas under their control, obtain social or status benefits associated with managing a large company, increase their remuneration (which may depend on the company’s size), and increase the importance of their competency for the company. The agency problem determines the availability of agency costs related to the excess diversification effect over expenditures and the need to strengthen monitoring and control of managers’ activities or to boost their motivation.

Elaborating on the agency problem of diversified companies, Scharfstein and Stein [46] introduced the term “socialism” in internal capital distribution, referring to weak divisions of a diversified company with low investment capability receiving more investment than stronger business units.

The work of Berger and Ofek [7] presents a methodology for qualitative assessment of diversification effects based on financial multipliers. The principle of the method is to compare the diversified company’s value with the value of similar companies doing business in the same areas. The difference constitutes a discount or a premium for diversification. Rajan et al. [8] and Lins and Servaes [47] studied the diversification discount and explained the nature of this discount. In general, a diversification discount means that diversified companies are underestimated compared to their analogues in the same segment.

The review of general ideas related to the value of diversification allows us to consider a multifactorial nature of its assessment. The significant number of competing aspects and their dynamic nature do not allow for a unified approach. It is safe to say that the assessments of the effect of diversification on companies’ efficiency and competitive ability, both practical and negative, are not univocal. The research does not give a comprehensive answer to the question of whether diversification is a win-win solution or an unjustified risk. Therefore, a question arises for further research: Why is diversification appealing to many companies? Our study reviews the problems related to this question based on the example of oil and gas companies.

3.2. Theoretical Aspects of Diversification of Oil and Gas Companies

For any vertically integrated oil company, business diversification is the only way to exist [48,49]. In general, building up the vertical production chain is one option for expanding business areas. In addition, the evolution of the global oil and gas industry is associated with a continuous change in the portfolio of key market players. Oil and gas companies increase their geographical coverage, transform their portfolios, and succeed in the market of power energy, renewable energy, and petrochemicals, and the technological development of the industry allows for new challenging categories of resources to be embraced.

Traditionally, mergers and acquisitions (M&A) have been considered as one of the main diversification tools for oil and gas companies. Generally, large companies strive to merge and acquire those players whose financial sustainability is in decline. A deal of this nature is guaranteed to ensure high competitive positions in the developed market segment with an established set of customers. It helps companies avoid the risks and expenditures involved in overcoming the barriers to entering the market, as well as other uncertainties.

The analysis of the scientific literature in the field showed limited interest by researchers in the aspects of diversification of oil and gas companies. Insufficient attention has been paid to the theoretical and methodological bases of diversification in this industry. The studies are generally of a selective nature and do not include analyses of the motivation behind and efficiency of diversification. Kretzschmar and Sharifzyanova analyzed the effects of international diversification on global asset ownership and control [50]; Antonakakis et al. proved the relationship between oil prices and the stock value of oil and gas companies [51]; Pickl [10], Oberling et al. [11], Hartmann et al. [12], and Hunt J et al. [52] studied the efficiency of investing in the clean power sector; and Kirichenko [53] offered a methodology for qualitatively assessing the diversification level. Thus, there is a need to expand the scope of theoretical research on the diversification process and its outcomes in the oil and gas sector.

Generally, the studies share the common thought that the areas and efficiency of diversification significantly depend on the development tendencies of the global energy market. At the same time, external environment parameters can be both drivers of and obstacles to successful diversification of oil and gas companies.

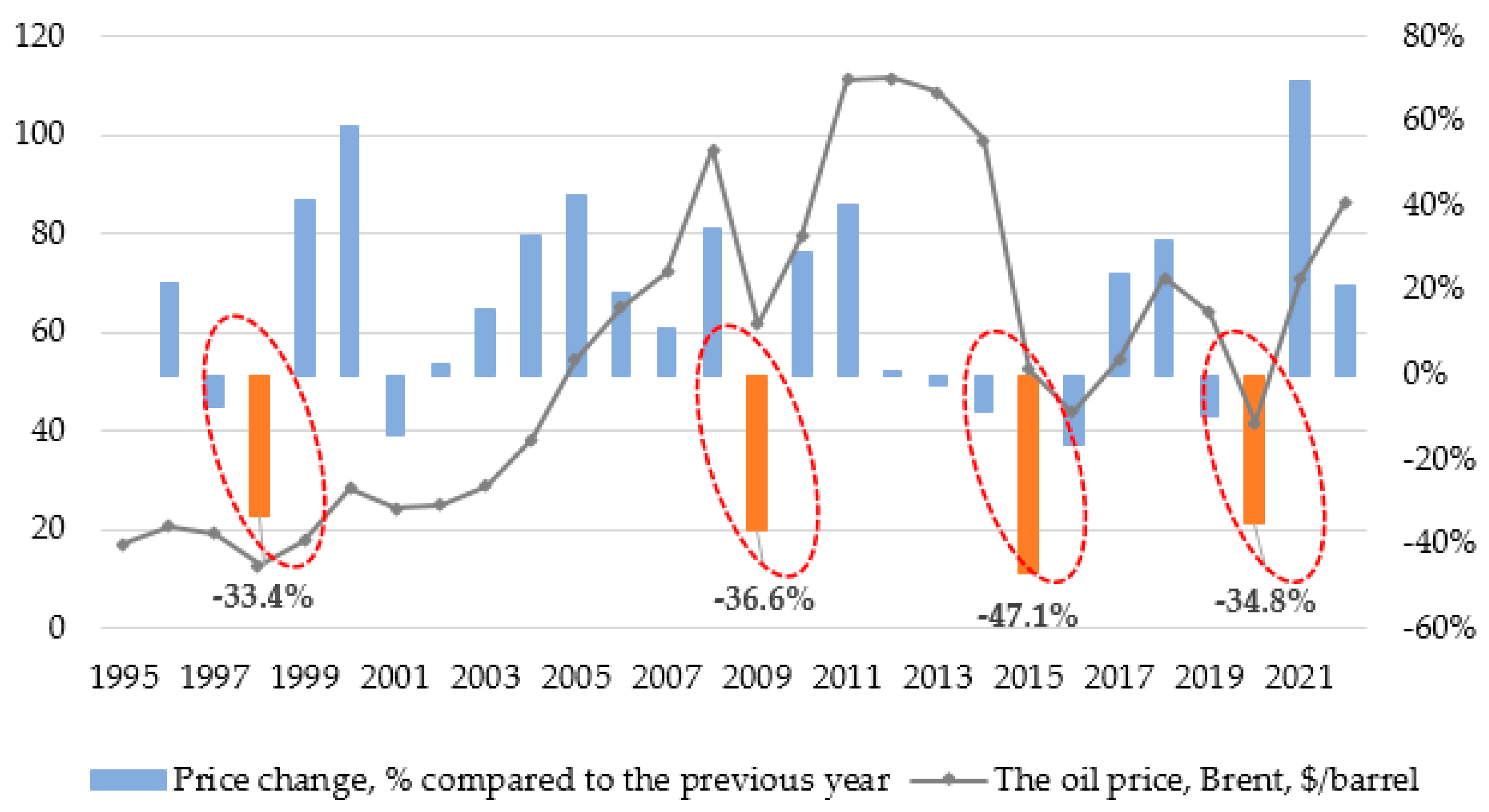

Therefore, it seems significant to analyze the strategic priorities of oil and gas companies and areas of diversification in crisis periods of market development. The results of analyzing oil pricing from 1995 to 2022 allowed us to identify four periods of rapid reduction in oil prices caused by shocks in the global economy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Oil price dynamics in 1995–2022. Source: Created by the authors using data from [54].

Table 1 lists the key development tendencies in the industry and the corresponding areas of strategic development of oil and gas companies during crisis periods.

Table 1.

Development tendencies in the oil and gas industry and strategic priorities of companies.

Therefore, it can be concluded that diversification strategies in the oil and gas industry have always been a way to minimize the risks caused by rapid changes in the prices of resources. The value of diversification, even under significant limiting factors, has never been questioned. Thus, the decreased interest in investing in the industry during periods of dropping oil prices requires the concentration of ownership capital in order to expand the scope of activities. In addition, international diversification is associated with high risk related to institutional features in the host country [50]. Moreover, developing hard-to-work resources such as arctic and deep-water fields and shale formations requires constant innovation and technology upgrades and developing corresponding competencies [55,56,57].

We can assume that it was the diversification strategy that allowed oil and gas companies to mitigate the adverse consequences of the economic unsustainability and price reduction of energy sources, secure investors’ confidence in the oil and gas industry, and restore performance indicators and profitability indices.

However, the energy crisis of 2020–2022 significantly differed from previous periods of decline, when it seemed obvious that oil and gas resources would remain the basis of the power system in the following decades, and the target of diversification strategies was to expand the resource base and build up hydrocarbon feed production.

Today, the key feature of international power system development is the evolution of the power balance or energy transition, which involves transitioning from carbon-intensive to a carbon-neutral energy and economy. Inter-fuel competition is becoming stronger and conventional energy resources are being replaced with renewable energy sources, such as wind, solar, wave energy, biofuel, hydrogen, etc. [58,59]. Meanwhile, gas retains its position as a more environmentally friendly type of fuel compared to oil. Another area is the development and use of technologies for decarbonizing the production of traditional energy sources (CO2 capture and storage technologies, electrification of field infrastructure, implementation of energy-efficient equipment, etc.).

Diversification of oil and gas companies takes on a fundamentally new nature. Large oil and gas companies adjust their development strategies: they reduce conventional international assets, discontinue carbon-intensive oil and gas projects, and increase the share of renewable energy sources and energy-efficient technologies in their asset portfolio [9,60]. At this time, it is difficult to fully assess the results of green diversification of oil and gas companies. Many market players are at the very beginning of their path toward adapting to the new energy balance, and their stated objectives are not always possible to implement in practice. In this study we attempt to form the main contours of the green diversification of oil and gas market players and reveal the key features and problems.

4. Results

The crisis in the fossil fuel market and the shifts in energy transition challenge the long-term sustainability of oil and gas corporations; however, they also reveal opportunities for developing new types of activities. The key factors that prompt oil and gas companies to adopt green diversification include the following [61,62,63,64]:

- Institutional factors (international and country-specific), which involve regulatory pressure and social pressure;

- Environmental factors, which involve reducing the negative impact of production processes on environmental systems;

- Economic factors, which involve finding growth points in new areas of activity to level the reduction in profit due to the production of conventional energy resources;

- Technological factors, which involve building up innovation and technology potential in prospective market segments;

- Reputational factors, which involve attracting investor interest in integrated portfolios with low carbon intensity;

- Strategic factors, which involve assuring flexibility and adaptability to changing conditions of a global nature.

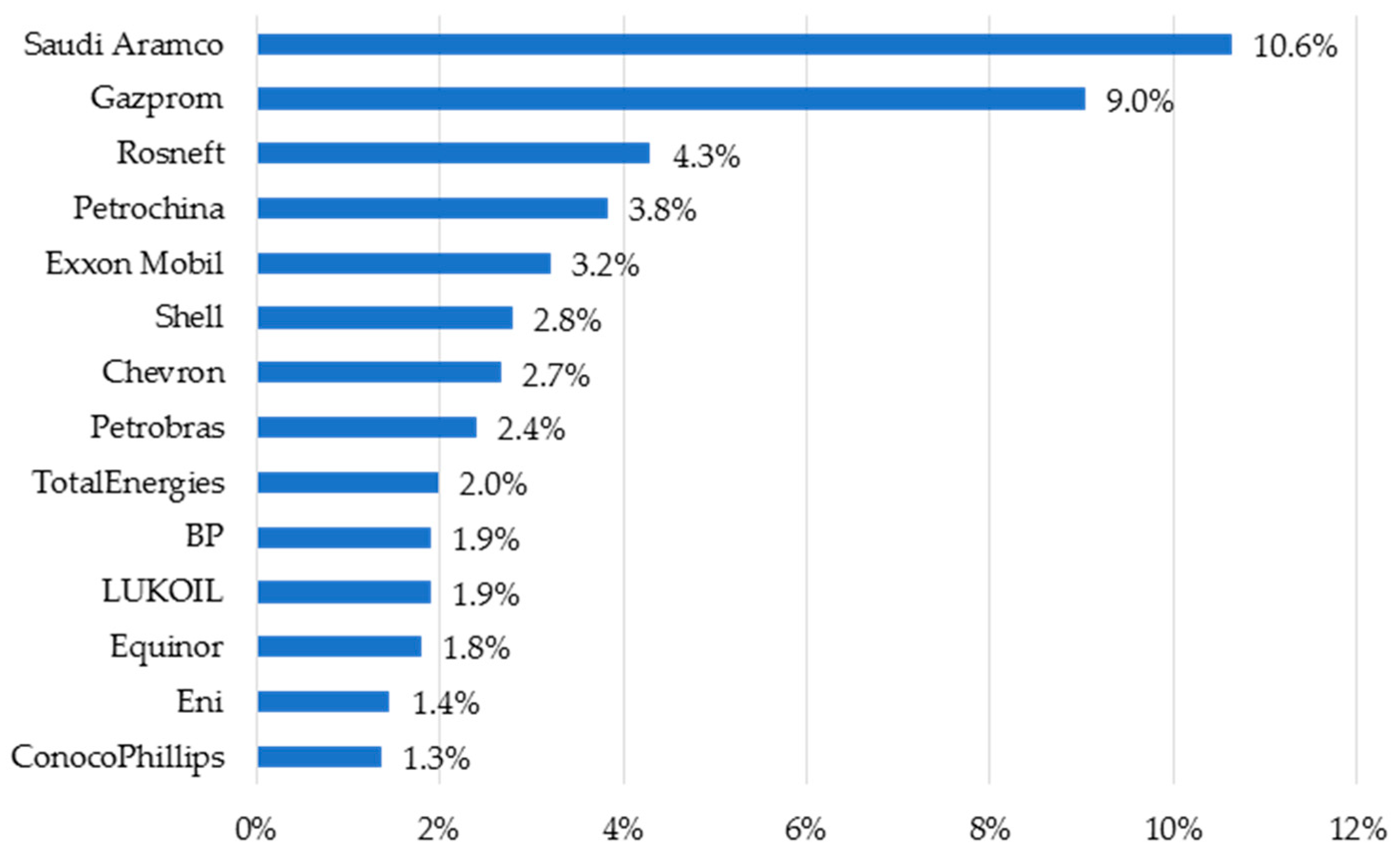

The areas of diversification of oil and gas companies under the conditions of energy transition were reviewed based on the example of 14 companies that accounted for 49% of the total international production of oil and gas resources in 2022 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Share of oil and gas resource production by largest global players in 2022. Source: Created by the authors using data from [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78].

Areas of green diversification that attract the greatest interest by oil and gas companies are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Key areas of green diversification of oil and gas companies.

Nowadays, renewable energy is the most rapidly growing sector of the energy market in terms of investments. Notwithstanding the significant number of technological breakthroughs in the renewables industry in recent years, return on investment is still lower for renewables projects than oil and gas production. However, renewables projects have significant competitive advantages: a lower level of risk due to the scale and short implementation cycle, widespread presence and availability of resources, and high environmental performance. Oil and gas companies often acquire shares in green energy projects or entire players involved in renewables. There has been a wave of mergers and acquisitions, as well as operations with individual assets, in the global M&A market. Internal projects are developed from scratch much less regularly as an alternative to organic growth.

Most oil and gas companies build up experience and expertise in multiple areas, while focusing on one or two of them. This is generally due to specific regional differences in the core business. The renewables market is developing unsteadily around the world and has different levels of maturity in developed and developing countries. At the same time, local drivers of growth in the market are observed in each region. Green diversification of oil and gas companies depends on the regions in which they are conducting business. For example, Shell and BP are mostly focused on biofuel (South America) and wind energy (Europe and USA); Equinor is one of the leaders in offshore wind power plants (North Sea); and Total and ENI are specialized in solar energy (Central and Southern Europe). This strategy allows companies to become centers of technological innovation and use their competencies for further geographic diversification.

However, no unified business model for renewables has been formed among oil and gas companies; each company develops a new strategy that reflects its long-term vision and current state of its core business (Table 3).

Table 3.

Goals and priority areas for the development of global oil and gas companies in the context of energy transition.

Changes in the global power balance structure determine significant shifts in the strategic planning and management of companies and stimulate the search for the optimal balance on the way from “oil” to “energy”. The key question here is what an oil and gas company’s portfolio will look like in 10 or 20 years. Even now, the key market players are trying to make this more stable, adaptable to global shocks, and less volatile.

According to Zhong and Brazilian [82] and Papadis and Tsatsaronis [83], green diversification is a complex and highly technological area that requires the maximum integration of resources, opportunities, experiences, and competencies of oil and gas companies. Companies recognize the high risk of implementing renewables projects. For example, Shell notes that, despite the advantages of new energy sources for a sustainable power system, the company still has not reached the stage where it can fully switch to renewables [65]. In addition, according to Djarbui’s analysis, the economic efficiency of renewables is a matter of discussion [84]. Therefore, oil and gas projects are still the basis of asset portfolios and are used to consolidate funds for investment in green energy. At the same time, companies are focused on implementing oil and gas projects with a low break-even point. Renewables are used primarily to diversify and strengthen the portfolio in response to market changes, secure the investors’ interest, and improve their reputation as a responsible and efficient producer.

The goal-oriented players, which mainly include European producers (Shell, BP, TotalEnergies, Eni), aim to become the leading producers of clean energy and hold high competitive positions in the market. In order to achieve the maximum effect from developing new portfolios, companies focus their efforts on implementing innovative technologies, building up investment in scientific developments in low-carbon solutions, and maintaining partnerships in the academic community.

It should be noted that green diversification requires developing individual business areas. Renewables projects have shorter design and development life cycles and are less capital-intensive. This calls for a business model that is different from the core activity. The need to create individual business units for efficient project management with a new business model determines the transformation of the organizational structure and management system and the arrangement of new schemes for interacting with organizations throughout the entire supply chain.

In this area, one representative example is Eni, an Italian company that created two new business groups. The Natural Resources division determines the perspectives in oil and gas production, taking into account the continuous technological development and enhancement of efficiency, to maximize cash flows. The activities of the Energy Evolution department are focused on business development in power generation from renewable energy sources and biomethane [66].

However, many companies (ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, Gazprom, Saudi Aramco) are less aggressive in their green diversification strategies. They take into account the fact that renewables projects are absolutely not the only way to accomplish decarbonization and adapt to energy transition trends [85,86]. These companies prefer to focus on improving the environmental sustainability of producing and transporting petroleum resources, and they display a strong interest in carbon capture, use, and storage (CCUS) technologies. Ilinova et al. [87] and Skobelev et al. [88] believe that CCUS technologies are the most efficient solution for the oil and gas industry. As Wang et al. state, many oil and gas production technologies can be integrated with CCUS, ensuring reduced carbon intensity of the products [89]. At the same time, Hastings and Smith note that oil and gas companies have the required range of technologies, experiences, and competencies to implement CCUS projects [90].

It should be noted that, most often, the decision to implement a renewables project is based not so much on considering the economic attractiveness of the new segment, but rather on responding to the pressure of policies, regulators, investors, and the community. Therefore, concerns arise in terms of the efficiency of capital distribution among business units. Agency theory takes on a new nature: the urge to become an energy transition leader can result in inefficient capital distribution, reduced economic efficiency, and diminished value. To date, significant investments in renewables have not guaranteed an increase in financial indicators, but at the same time, hydrocarbon production will be reduced due to underinvestment in conventional areas. Therefore, decisions on investment distribution should be based on a phased strategic analysis of perspectives in each area, the parameters of the company’s technological development, and the specific features of the global market.

As noted by Pickl, there is a high correlation between the level of proven reserves of oil and gas companies and their strategies with regard to renewable energy sources [10]. To elaborate on this point, we propose differentiating companies according to the level of reserves and assuming the direction of their long-term strategic development (Table 4).

Table 4.

Potential areas for the development of global oil and gas companies in the context of energy transition.

5. Discussion

The global shocks of the energy market, the evolution of power balance, and the actualization of the climate-related agenda justify systematic changes in the strategies of oil and gas companies. Today, enormous resource potential is not a key advantage; the focus is mainly on the capability of companies to contribute to the transition to decarbonized energy and economy.

The diversification strategy that proved to be an effective tool during periods of macroeconomic turbulence is still used in the oil and gas industry. Some companies use the opportunity to build up their production of gas as the most environmentally friendly fossil fuel; they also discard exploration projects for complicated categories of reserves, trying to create an environmentally friendly and highly profitable portfolio of oil and gas assets. However, as the global economy progresses toward net zero, this is not enough.

Today, investments in renewables hold a specific position in the long-term development strategies of oil and gas companies. Using the advantages of synergy with the core business, experience with implementing high-technology projects, and developed sales channels, oil and gas companies readily assert themselves in the new segment, despite the presence of specialized players in the renewables market.

At this point, it is difficult to assess to what extent the stated objectives for green diversification will be implemented in practice and how portfolio diversification will affect the long-term sustainability of oil and gas companies. Conventional hydrocarbon resources will remain in demand for many more years. However, the production of hydrocarbons has become increasingly more complicated and cost-intensive, while the increasing global need for energy creates opportunities for renewables to compete in terms of profitability and attractiveness.

The green diversification strategy is aimed at two key areas. First, it can contribute to the decarbonization of the global economy and the power system, and it can assist in solving climate-related problems. However, even though the environmental aspects are significant, they are not the only motivation. The second aim of green diversification is to hold a steady competitive position in the rapidly growing renewables market and to retain a high level of financial indicators during periods of stagnation of the conventional hydrocarbons market.

Nowadays, green diversification is considered as a tool for improving sustainability in both the short term and the long term under changing market conditions. Participating in renewables projects will help improve the reputation of oil and gas companies in the global market and create a technological base for complying with the requirements of the changing power consumption balance.

Research on green diversification of oil and gas companies raises several significant questions for further research:

- What should the level of green diversification be? On the one hand, analyzing the optimal ratio of conventional energy sources and renewables in the asset portfolio to ensure high profitability and efficiency and, on the other hand, analyzing energy security and the availability of resources for the global economy seem significant, as well as analyzing such ratios taking into account the emerging aspects of power energy market development.

- Which criteria should be the basis for making decisions on capital distribution? Should financial or environmental criteria be the priority? In addition, assessing the level of influence of regulatory climate norms on the level of potential investments could be a prospective area for research.

6. Conclusions

Research on the conceptual basis of diversification leads to a conclusion pointing to two opposite opinions. One group of researchers consider diversification to be the most efficient way to develop a company; they empirically prove the relationship between diversification and improved competitive ability and sustainability. On the contrary, others find arguments for the idea that diversification does not result in long-term benefits. The multifactorial nature of assessment and the inconsistency of evidence do not allow us to conclude that there is a model for assessing diversification today that is applicable and universal.

In this study we reviewed the key ideas of the green diversification strategy of oil and gas companies under the conditions of the transformation of the global power system, revealed the prerequisites to large-scale implementation of renewables projects, and determined the priorities of key market players in terms of strategic development. The analysis allowed us to formulate the key principles of implementing green diversification by oil and gas companies in the process of strategic planning:

- Conduct a strategic assessment of renewables projects in terms of strengthening the company’s competitive position in the market and adapt the portfolio structure to changing conditions;

- Test the strategy in different scenarios, taking into account global and local tendencies, including economic, political, technological, and social features, and the scenarios of technological development and climate-related risks;

- Analyze new low-carbon capabilities and technologies that can be closely integrated with the company’s global operations, markets, and competencies;

- Plan new operating models that ensure the adaptability of production processes and the possibility to respond promptly to external changes;

- Analyze the capability of developing partnerships with renewables market participants, equipment and technologies suppliers, and the scientific community based on mutual development and integration of knowledge and experience;

- Develop managerial and engineering competencies in the field of renewables to accelerate the development of new and valuable solutions.

The theoretical aspects of implementing green transformation by oil and gas companies reviewed in the study provide a methodological basis for large-scale research on the efficiency of diversification strategies with a forecast of long-term effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., A.K. and E.R.; methodology, E.R.; research algorithm, A.C., A.K. and E.R.; validation, A.C. and E.R., formal analysis, A.C., A.K. and E.R.; investigation, A.C. and E.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C., A.K. and E.R.; writing—review and editing, A.C. and A.K.; visualization, E.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Goold, M.; Luchs, K. Why diversify? Four decades of management thinking. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1993, 7, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amihud, Y.; Lev, B. Risk Reduction as a Managerial Motive for Conglomerate Mergers. Bell J. Econ. 1981, 12, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y. Corporate diversification, investment efficiency and the business cycle. J. Corp. Financ. 2023, 78, 102353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.C. Internal Capital Markets and the Competition for Corporate Resources. J. Financ. 1997, 52, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palich, L.E.; Cardinal, L.B.; Miller, C.C. Curvilinearity in the diversification-performance linkage: An examination of over three decades of research. Strat. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, D.J.; Denis, D.K.; Sarin, A. Agency Problems, Equity Ownership, and Corporate Diversification. J. Financ. 1997, 52, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P.G.; Ofek, E. Diversification’s Effect on Firm Value. J. Financ. Econ. 1995, 37, 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, R.; Servaes, H.; Zingales, L. The Cost of Diversity: The Diversification Discount and Inefficient Investment. J. Financ. 2000, 55, 35–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romasheva, N.; Cherepovitsyna, A. Renewable Energy Sources in Decarbonization: The Case of Foreign and Russian Oil and Gas Companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickl, M.J. The renewable energy strategies of oil majors—From oil to energy? Energy Strat. Rev. 2019, 26, 100370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberling, D.F.; Obermaier, M.; Szklo, A.; La Rovere, E.L. Investments of oil majors in liquid biofuels: The role of diversification, integration and technological lock-ins. Biomass-Bioenergy 2012, 46, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, J.; Inkpen, A.C.; Ramaswamy, K. Different shades of green: Global oil and gas companies and renewable energy. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2021, 52, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherepovitsyna, A.; Sheveleva, N.; Riadinskaia, A.; Danilin, K. Decarbonization Measures: A Real Effect or Just a Declaration? An Assessment of Oil and Gas Companies’ Progress towards Carbon Neutrality. Energies 2023, 16, 3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.A.; Strickland, A.J. Strategic Management: Concepts and Case; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gort, M. Diversification and Integration in American Industry; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, C.H. Corporate Growth and Diversification.Princeton; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts, R.A.; Hopkins, H.D. Firm diversity: Conceptualization and measurement. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansoff, H.I. Strategies for diversification. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1957, 35, 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Rumelt, R.P. Strategy, Structure, and Economic Performance; Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University: Boston, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanujam, V.; Varadarajan, P. Research on corporate diversification: A synthesis. Strat. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 523–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C. The Effects of Prior Performance on the Choice Between Related and Unrelated Acquisitions: Implications for the Performance Consequences of Diversification Strategy. J. Manag. Stud. 2002, 39, 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picone, P.M.; Dagnino, G.B. Revamping research on unrelated diversification strategy: Perspectives, opportunities and challenges for future inquiry. J. Manag. Gov. 2016, 20, 413–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, S.; Dhir, S. Diversification: Literature Review and Issues. Strat. Chang. 2015, 24, 569–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerras-Martín, L.; Ronda-Pupo, G.A.; Zúñiga-Vicente, J.; Benito-Osorio, D. Half a century of research on corporate diversification: A new comprehensive framework. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 114, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.K.; Samwick, A.A. Why Do Managers Diversify Their Firms? Agency Reconsidered. J. Financ. 2003, 58, 71–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, P.; Rothchild, J. One up on Wall Street: How to Use What you Already know to make Money in the Market; Simon and Schuster: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, T.J.; Waterman, R.H. In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best Run Companies; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1982; 360p. [Google Scholar]

- Liebeskind, J.P. Internal Capital Markets: Benefits, Costs, and Organizational Arrangements. Organ. Sci. 2000, 11, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsusaka, J.G.; Nanda, V.K. Internal Capital Markets and Corporate Refocusing. J. Financ. Intermediat. 2002, 11, 176–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, B. Henderson on Corporate Strategy; New American Library: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hauschild, S.; Knyphausen-Aufseß, D.Z. The resource-based view of diversification success: Conceptual issues, methodological flaws, and future directions. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2013, 7, 327–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, C.A. Corporate Diversification. J. Econ. Perspect. 1994, 8, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chkir, I.E.; Cosset, J.-C. Diversification strategy and capital structure of multinational corporations. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2001, 11, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Prada, P.; Delgado-Rodriguez, M.J.; Romero-Jordán, D. Effect of product and geographic diversification on company performance: Evidence during an economic crisis. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Qian, Z. Regional diversification and firm performance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2008, 39, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neffke, F.; Henning, M. Skill relatedness and firm diversification. Strat. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, G.; Yang, L. The Bright Side of Corporate Diversification: Evidence from Internal Labor Markets. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2015, 28, 2203–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiglianu, P.; Romasheva, N.; Nenko, A. Conceptual Management Framework for Oil and Gas Engineering Project Implementation. Resources 2023, 12, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokbolat, Y.; Le, H. COVID-19: Corporate diversification and post-crash returns. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 46, 102501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppuswamy, V.; Villalonga, B. Does Diversification Create Value in the Presence of External Financing Constraints? Evidence from the 2007–2009 Financial Crisis. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 905–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matvos, G.; Seru, A. Resource Allocation within Firms and Financial Market Dislocation: Evidence from Diversified Conglomerates. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2014, 27, 1143–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, N.I.; Smith, G.C. Corporate diversification and firm value during economic downturns. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2015, 55, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aivazian, V.A.; Rahaman, M.M.; Zhou, S. Does corporate diversification provide insurance against economic disruptions? J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M.; Jammine, A.P.; Thomas, H. Diversity, Diversification, and Profitability among British Manufacturing Companies, 1972–1984. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 31, 771–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharfstein, D.S.; Stein, J.C. The Dark Side of Internal Capital Markets: Divisional Rent-Seeking and Inefficient Investment. J. Financ. 2000, 55, 2537–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, K.; Servaes, H. International Evidence on the Value of Corporate Diversification. J. Financ. 1999, 54, 2215–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C. Global energy networks: Geographies of mergers and acquisitions of worldwide oil companies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 139, 110698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkpen, A.; Ramaswamy, K. Breaking up global value chains: Evidence from the global oil and gas industry. In Breaking Up the Global Value Chain; Emerald Publishing Ltd.: Bingley, UK, 2017; Volume 30, pp. 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar, G.L.; Sharifzyanova, L. Limits to international diversification in oil & gas–Domestic vs foreign asset control. Energy 2010, 35, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakakis, N.; Cunado, J.; Filis, G.; Gabauer, D.; de Gracia, F.P. Oil volatility, oil and gas firms and portfolio diversification. Energy Econ. 2018, 70, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.D.; Nascimento, A.; Nascimento, N.; Vieira, L.W.; Romero, O.J. Possible pathways for oil and gas companies in a sustainable future: From the perspective of a hydrogen economy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 160, 112291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirichenko, O.S. Diversification of Russian oil and gas upstream companies. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2020, 10, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA (2022), World Energy Outlook 2022, IEA, Paris, License: CC BY 4.0 (report); CC BY NC SA 4.0 (Annex A). Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2022 (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Dmitrieva, D.; Chanysheva, A.; Solovyova, V. A Conceptual Model for the Sustainable Development of the Arctic’s Mineral Resources Considering Current Global Trends: Future Scenarios, Key Actors, and Recommendations. Resources 2023, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, T. Value Improving Practices in Production of Hydrocarbon Resources in the Arctic Regions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogoyavlensky, V.; Kishankov, A.; Kazanin, A. Evidence of large-scale absence of frozen ground and gas hy-drates in the northern part of the East Siberian Arctic shelf (Laptev and East Siberian seas). Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 148, 106050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Wang, L.; Belgacem, S.B.; Pawar, P.S.; Najam, H.; Abbas, J. Investment in renewable energy and electricity output: Role of green finance, environmental tax, and geopolitical risk: Empirical evidence from China. Energy 2023, 269, 126683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewski, P.; Drożdż, W.; Lewicki, W.; Dowejko, J. Total Cost of Ownership and Its Potential Consequences for the Development of the Hydrogen Fuel Cell Powered Vehicle Market in Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenner, D.; Heede, R. White knights, or horsemen of the apocalypse? Prospects for Big Oil to align emissions with a 1.5 °C pathway. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 79, 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedosekin, A.O.; Rejshahrit, E.I.; Kozlovskij, A.N. Strategic approach to assessing economic sustainability objects of mineral resources sector of Russia. J. Min. Inst. 2019, 237, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinova, E.; Ponomarenko, T.; Tesovskaya, S. Key Corporate Sustainability Assessment Methods for Coal Companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Qu, Y.; Ye, Y. The Effect of International Diversification on Sustainable Development: The Mediating Role of Dynamic Capabilities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgunova, M.; Shaton, K. The role of incumbents in energy transitions: Investigating the perceptions and strategies of the oil and gas industry. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 89, 102573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainability Report 2022; Shell: London, UK. 2022. Available online: https://reports.shell.com/sustainability-report/2022/ (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Publications 2022; Eni: Rome, Italy. Available online: https://www.eni.com/en-IT/publications/2022.html (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Advancing Climate Solutions Progress Report; ExxonMobil: Irving, TX, USA. 2023. Available online: https://corporate.exxonmobil.com/news/reporting-and-publications/advancing-climate-solutions-progress-report (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Reporting Centre; Equinor: Stavanger, Norway. Available online: https://www.equinor.com/sustainability/reporting (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Sustainability; BP: London, UK. Available online: https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/sustainability.html (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Climate Change and Transitioning to Low Carbon; Petrobras: Janeiro, Brazil. Available online: https://petrobras.com.br/en/society-and-environment/environment/climate-changes/ (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Sustainability & Climate 2023 Progress Report; TotalEnergies: Courbevoie, France. 2023. Available online: https://totalenergies.com/system/files/documents/2023-03/Sustainability_Climate_2023_Progress_Report_EN.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Sustainability. Our Approach to Sustainability; Saudi Aramco: Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://www.aramco.com/en/sustainability/our-approach-to-sustainability (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Sustainability. Advancing a Lower Carbon Future; Chevron: San Ramon, CA, USA. Available online: https://www.chevron.com/sustainability (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Sustainability Reporting, ConocoPhillips: Houston, TX, USA. Available online: https://www.conocophillips.com/company-reports-resources/sustainability-reporting/ (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Environmental Social and Governance Report, 2022; PetroChina Company Limited: Beijing, China. 2022. Available online: http://www.petrochina.com.cn/ptr/xhtml/images/shyhj/2022esgen.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Sustainable Development. Gazprom: Moscow, Russia. Available online: https://www.gazprom.ru/sustainability/ (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Sustainability Report. LUKOIL: Moscow, Russia. Available online: https://www.lukoil.com/Sustainability/SustainabilityReport (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Sustainability Reports. Rosneft: Moscow, Russia. Available online: https://www.rosneft.ru/Development/reports/ (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Kopteva, A.; Kalimullin, L.; Tcvetkov, P.; Soares, A. Prospects and Obstacles for Green Hydrogen Production in Russia. Energies 2021, 14, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkitie, T.; Normann, H.E.; Thune, T.M.; Gonzalez, J.S. The green flings: Norwegian oil and gas industry’s engagement in offshore wind power. Energy Policy 2019, 127, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Hydrogen economy for sustainable development in GCC countries: A SWOT analysis considering current situation, challenges, and prospects. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 10315–10344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Bazilian, M.D. Contours of the energy transition: Investment by international oil and gas companies in renewable energy. Electr. J. 2018, 31, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadis, E.; Tsatsaronis, G. Challenges in the decarbonization of the energy sector. Energy 2020, 205, 118025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarboui, S. Renewable energies and operational and environmental efficiencies of the US oil and gas companies: A True Fixed Effect model. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 8667–8676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tcvetkov, P. Climate Policy Imbalance in the Energy Sector: Time to Focus on the Value of CO2 Utilization. Energies 2021, 14, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasani, M.; Sarker, S.; Kabir, G.; Ali, S.M. Evaluating strategies to decarbonize oil and gas supply chain: Implications for energy policies in emerging economies. Energy 2022, 258, 124805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilinova, A.A.; Romasheva, N.V.; Stroykov, G.A. Prospects and social effects of carbon dioxide sequestration and utilization projects. J. Min. Inst. 2020, 244, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skobelev, D.O.; Cherepovitsyna, A.A.; Guseva, T.V. Carbon capture and storage: Net zero contribution and cost estimation approaches. J. Min. Inst. 2023, 259, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Jin, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, K. Oil and gas pathway to net-zero: Review and outlook. Energy Strat. Rev. 2023, 45, 101048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, A.; Smith, P. Achieving Net Zero Emissions Requires the Knowledge and Skills of the Oil and Gas Industry. Front. Clim. 2020, 2, 601778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).