Overcoming the Challenge of Exploration: Organizational Readiness of Technology Entrepreneurship on the Background of Energy Climate Nexus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

| Conceptual Definition | Authors and Years |

|---|---|

| People’s beliefs, attitudes, and intentions regarding the extent to which changes are needed and the organization’s capacity to make those changes | Armenakis et al. (1993) [27] |

| State of mind about the need for innovation and the capacity to undertake technology transfer | Backer (1995) [28] |

| State of mind that is the precursor of actual behaviors needed to adopt an innovation (or to resist it) | Backer (1997) [29] |

| Conceptualized in terms of an individual’s perception of a specific facet of his/her work environment: the extent to which the organization is perceived to be ready to take on large-scale change | Eby et al. (2000) [30] |

| Preparation for and support of the change by the organization’s members | Armenakis et al. (2002) [31] |

| The extent to which staff are aware of the need for change, understand the extent and implications of the change, and are motivated toward achieving the change | Hailey et al. (2002) [32] |

| An organization’s plan for change and its ability to execute it | Narine et al. (2003) [33] |

| Capacity to implement change designed to improve performance | Deveraux et al. (2006) [34] |

| Beliefs among employees that they are capable of implementing a proposed change the proposed change is appropriate for the organization, the leaders are committed to the proposed change, and the proposed change is beneficial to organizational members | Holt et al. (2007) [35] |

| The extent to which organizational members are psychologically and behaviorally prepared to implement organizational change | Weiner et al. (2008) [36] |

| A shared psychological state in which organizational members feel committed to implementing an organizational change and confident in their collective abilities to do so | Weiner (2009) [37] |

| The degree to which those involved in a change initiative are individually and collectively primed, motivated, and technically capable of executing the change | Hannon et al. (2017) [38] |

| Shared resolution by organizational members to implement change | Al-Maamari et al. (2018) [39] |

3. Methodology

| Dimensions | Construct Level | Citation Authors |

|---|---|---|

| The first level | Lehman et al. (2002) [23] |

| Unidimensionality | The first level | Simpson et al. (2007) [23] |

| The first level | Meliyanti (2015) [58] |

| The second level | Ingersoll, et al. (2000) [59] |

| Organizational members agreement and willingness to work toward the change goal | The second level | Jansen et al. (2004) [60] |

| The second level | Holt et al. (2007) [35] |

4. Results and Discussion

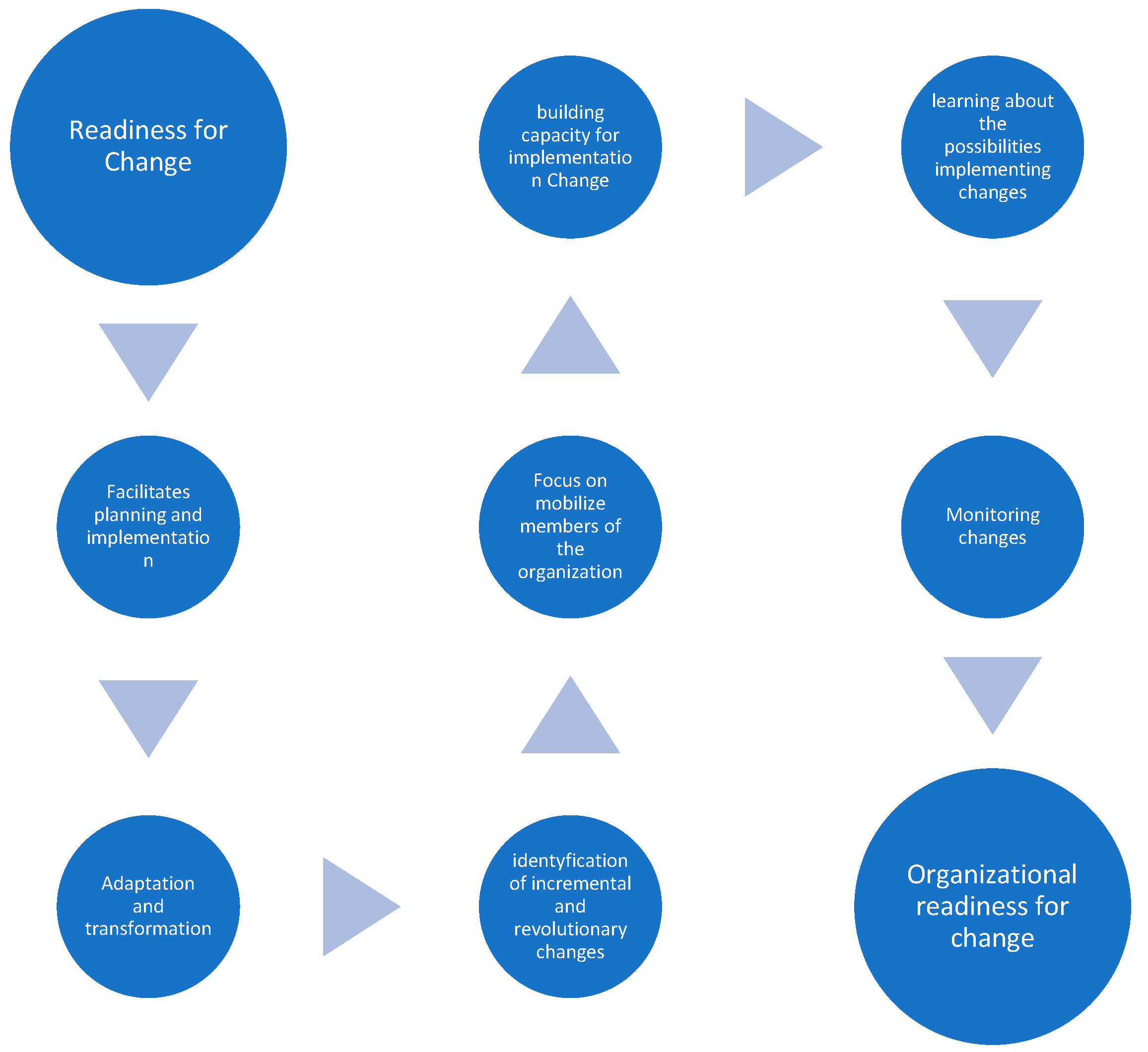

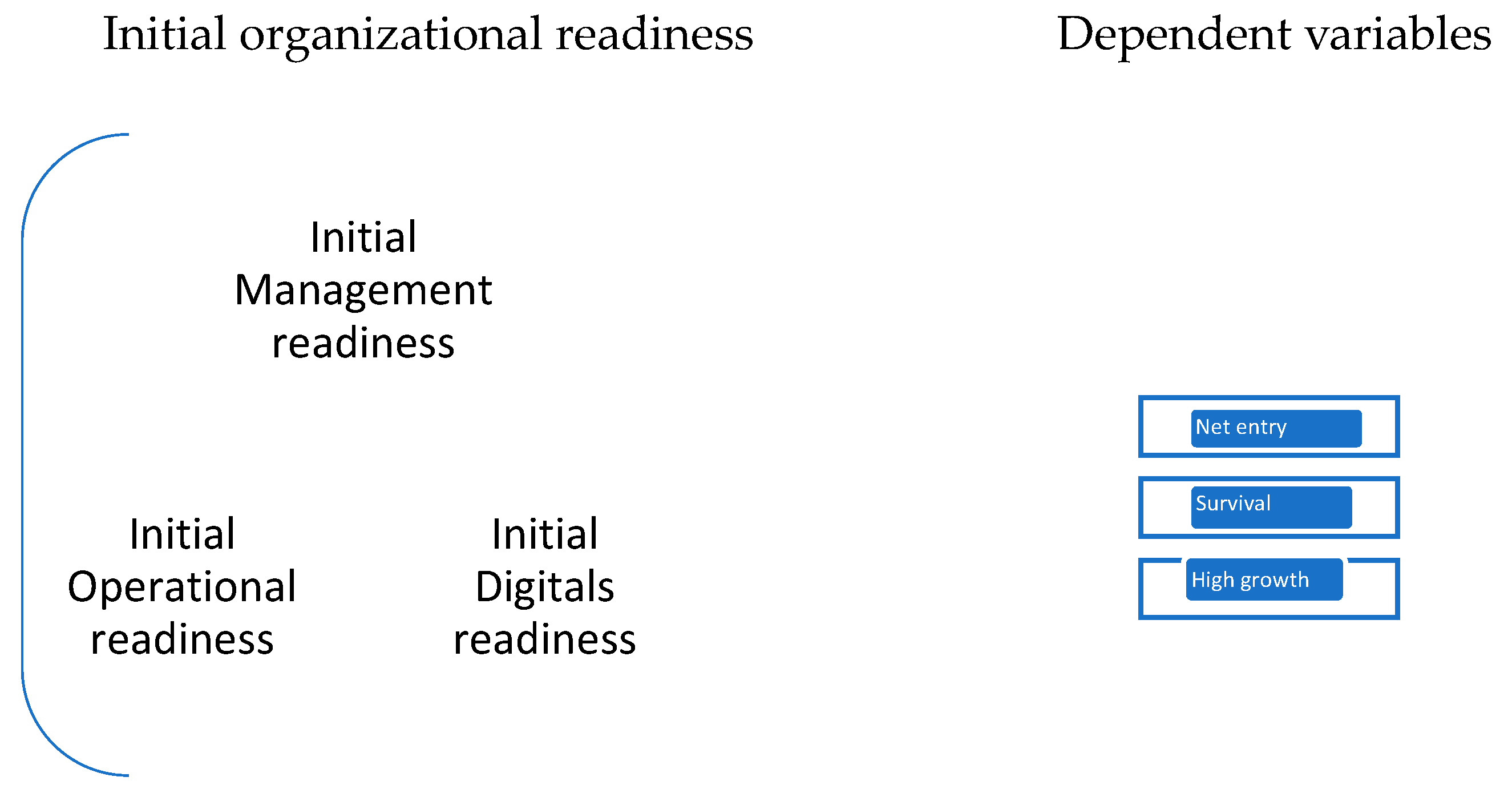

- Initial Management Readiness: This refers to the overall preparedness of the organization as a whole, including the alignment of its culture, leadership, and workforce toward embracing and executing change. It involves having clear communication channels, strong leadership commitment, and an engaged workforce that understands and supports the strategic objectives.

- Initial Digital Readiness: This focuses on the preparedness of specific programs or initiatives within the organization. It involves having the necessary resources, tools, and plans in place to ensure the successful implementation of new processes, technologies, or strategies. Program readiness ensures that each initiative is fully supported and that teams have the capacity and capabilities to deliver results.

- Initial Operational Readiness: This aspect pertains to the day-to-day operational capability of the organization to adapt to new processes and systems. It includes the readiness of infrastructure, such as IT systems and operational frameworks, to support the changes being introduced. Operational readiness ensures that the practical, on-the-ground implementation of changes is smooth and that any potential disruptions are minimized.

- The ability of the business to identify and prioritize issues and establish relevant KPIs.

- The readiness of IT infrastructure and applications to support dynamic KPI initiatives.

- The deployment of effective change management processes to modify practices and behaviors, ensuring the achievement of KPI targets.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Treuer, K.; Karantzas, G.; McGabe, M.; Konis, A.; Davison, T.E.; O’Connor, D. Organizational factors associated with readiness for change in residential aged care settings. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amendola, M.; Lamperti, F.; Roventini, A.; Sapio, A. Energy Efficiency Policies in an Agent-Based Macroeconomic Model. Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2024, 68, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q.; Viktor, P.; Al-Musawi, T.J.; Mahmood Ali, B.; Algburi, S.; Alzoubi, H.M.; Khudhair Al-Jiboory, A.; Zuhair Sameen, A.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. The Renewable Energy Role in the Global Energy Transformations. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 48, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemizadeh, A.; Ju, Y.; Abade, F.Z.B. Policy design for renewable energy development based on government support: A system dynamics model. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Foggia, G.; Beccarello, M. European Roadmaps to Achieving 2030 Renewable Energy Targets. Util. Policy 2024, 88, 101729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, M.; Geitner, L.; Brennan, A.; McAvoy, J. A Review of the Success and Failure Factors for Change Management. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2022, 50, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øygarden, O.; Mikkelsen, A. Readiness for Change and Good Translations. J. Chang. Manag. 2020, 20, 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lausier, M.; Lemieux, N.; Montreuil, V.L.; Nicolas, C. On the transposability of change management research results: A systematic scoping review of studies published in JOCM and JCM. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2020, 33, 859–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.; Hegarty, J.; Barry, J.; Dyer, K.R.; Horgan, A. A systematic review of the relationship between staff perceptions of organizational readiness to change and the process of innovation adoption in substance misuse treatment programs. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2017, 80, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billsten, J.; Fridell, M.; Holmberg, R.; Ivarsson, A. Organizational Readiness for Change (ORC) test used in the implementation of assessment instruments and treatment methods in a Swedish National study. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2018, 84, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alolabi, A.; Ayupp, K.; Dwaikat, M.A. Issue and implications of readiness to change. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorca, M.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, A. Economic, environmental, and energy equity convergence: Evidence of a multi-speed Europe? Ecol. Econ. 2024, 219, 108133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosin, A.F.; Proksch, D.; Stubner, S.; Pinkwart, A. Digital new ventures: Assessing the benefits of digitalization in entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Strategy 2020, 30, 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Faulks, B.; Yinghua, S.; Khudaykulov, A.; Jumanov, A. Exploring organizational Readiness to change and learn: A Scival analysis from 2012 to 2021. J. Int. Bus. Reseach Mark. 2023, 7, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, J.; Hultman, K. Self and Identity: Hidden Factors in Resistance to Organizational Change. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 36, 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wulandari, R.D.; Supriyanto, S.; Qomaruddin, M.B.; Damayanti, N.A.; Laksono, A.D. Role of leaders in building organizational readiness to change-Case study at public health centers in Indonesia. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2023, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standal, K.; Leiren, M.D.; Alonso, I.; Azevedo, I.; Kudrenickis, I.; Maleki-Dizaji, P.; Laes, E.; Di Nucci, M.R.; Krug, M. Can Renewable Energy Communities Enable a Just Energy Transition? Exploring Alignment Between Stakeholder Motivations and Needs and EU Policy in Latvia, Norway, Portugal and Spain. Energy Res. Soc. Sci 2023, 106, 103326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Segura, F.J.; Osorio-Aravena, J.C.; Frolova, M.; Terrados-Cepeda, J.; Muñoz-Cerón, E. Social Acceptance of Renewable Energy Development in Southern Spain: Exploring Tendencies, Locations, Criteria and Situations. Energy Policy 2023, 173, 113356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miake-Lye, I.M.; Delevan, D.M.; Ganz, D.A. Unpacking organizational readiness for change: An updated systematic review and content analysis of assessments. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.Y.; Chien, S.C. The influences of technology development on economic performance—The example of ASEAN countries. Technovation 2007, 27, 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Dong, J.Q.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, D.; Hutchins, K. A Machiavellian analysis of organizational change. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2006, 19, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, W.E.K.; Greener, J.M.; Simpson, D.D. Assessing organizational readiness for change. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2002, 22, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uluskan, M.; McCreery, J.K.; Rothenberg, L. Impact of quality management practices on change readiness due to new quality implementations. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2018, 9, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thundiyil, T.G.; Manning, M.; Richard, W. Woodman: Creativity and Change. In The Palgrave Handbook of Organizational Change Thinkers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1461–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, K.J.; Conn, A.B.; Sorra, J.S. Implementing computerized technology: An organizational analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armenakis, A.A.; Harris, S.G.; Mossholder, K.W. Creating readiness for organizational change. Hum. Relat. 1993, 46, 681–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, T.E. Assessing and enhancing readiness for change: Implications for technology transfer. NIDA Res. Monogr. 1995, 155, 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, B. Sustainability Assessment: A Review of Values, Concepts and Methodological Approaches; Issues in Agricuture 10; CGIAR World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Eby, L.T.; Adams, D.M.; Russell, J.E.; Gaby, S.H. Perceptions of organizational readiness for change: Factors related to employees’ reactions to the implementation of team-based selling. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilles, A.; Armenakis, A.; Harris, S.G. Crafting a change message to create transformational readiness. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2002, 15, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailey, V.H.; Balogun, J. Devising context sensitive approaches to change: The example of Glaxo Welcome. Long Range Plan. 2002, 35, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narine, L.; Persaud, D. Gaining and maintaining commitment to large-scale change in healthcare organizations. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 2003, 16, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devereaux, M.W.; Drynan, A.K.; Lowry, S.; MacLennan, D.; Figdor, M.; Fancott, C. Evaluating organizational readiness for change: A preliminary mixed-model assessment of an interprofessional rehabilitation hospital. Healthc. Q. 2006, 9, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, D.T.; Armenakis, A.A.; Field, H.S.; Harris, S.G. Readiness for organizational change: The systematic development of a scale. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2007, 43, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B.J.; Amick, H.; Lee, S.Y. Conceptualization and measurement of organizational readiness for change: A review of the literature in health services research and other fields. Med. Care Rev. 2008, 65, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, B.J. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannon, P.A.; Helfrich, C.D.; Chan, K.G.; Allen, C.L.; Hammerback, K.; Kohn, M.J.; Parrish, A.T.; Weiner, B.J.; Harris, J.R. Development and pilot test of the workplace readiness questionnaire, a theory-based instrument to measure small workplaces’ readiness to implement wellness programs. Am. J. Health Promot. 2017, 31, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maamari, Q.A.; Rezian-na, M.K.; Valliappan, R.; Al-Tahitah, A.; Abdulbaqi, A.A.; Abdulrab, M. Factors affecting indvidual readiness for change: A conceptual framework. Int. J. Manag. Hum. Sci. 2018, 2, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, C.M.; Jacobs, S.R.; Esserman, D.A.; Bruce, K.; Weiner, B.J. Organizational readiness for implementing change: A psychometric assessment of a new measure. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenakis, A.A.; Bernerth, J.B.; Pitts, J.P.; Walker, H.J. Organizational change recipients’ beliefs scale: Development of an Assessment Instrument. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2007, 43, 403–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.; Zahid, S.; Kashif, U.; Ilyas, S.M. Role of leader-member exchange relationship in organizational change management: Mediating role of organizational culture. Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2017, 6, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, H.H.; West, R.; Twine, R.; Masilela, N.; Steward, W.T.; Kahn, K.; Lippman, S.A. Measuring organizational readiness for implementing change in primary care facilities in rural Bushbuckridge, South Africa. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2020, 11, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

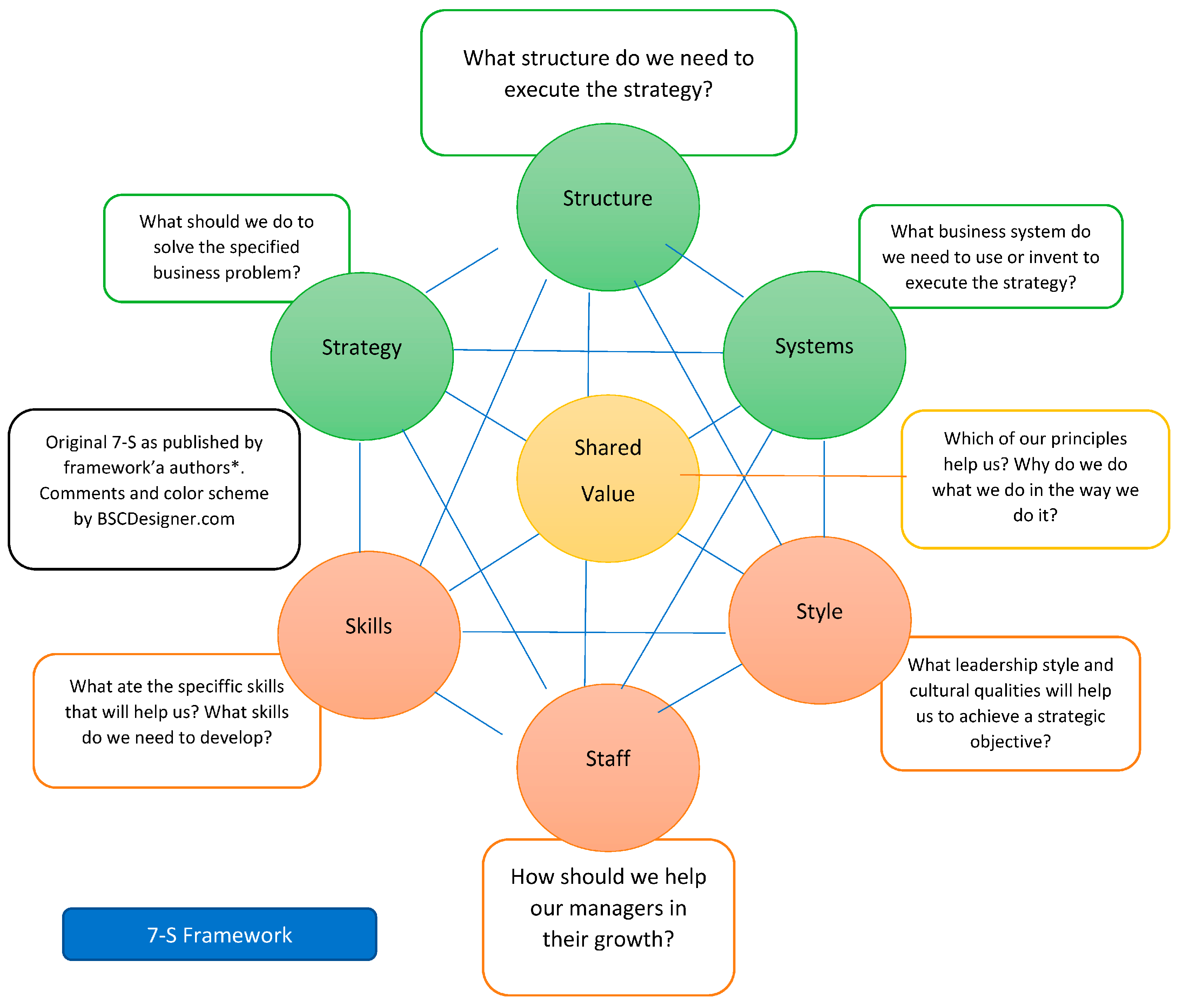

- Nugrogo, B. Literature reviews: McKinsey 7S model to support organizational performance. Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 2022, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, A.D. Analysis of Company Capability Using 7S McKinsey Framework to support Corporate Succession. Manaj. Bisnis 2021, 11, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inuwa, M.; Suzari, B.A.R. Lean readiness factors and organizational readiness for change manufacturing smes: The role of organizational culture. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 2394–5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrin, S.; Korosteleva, J.; Mickiewicz, T. Schumpeterian entry: Innovation, exporting, and growth aspirations of entrepreneurs. Enterpreneursip Theory Pract. 2020, 46, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.; Heaton, S.; Urbano, D. Building universities’ _intrapreneurial capabilities in the digital era: The role and impacts of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). Technovation 2021, 99, 102139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarli, T.; Kenney, M.; Massini, S.; Piscitello, L. Digital technologies, innovation, and skills: Emerging trajectories and challenges. Res. Policy 2021, 50, 104289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embriyono, A.B.; Sukoco, B.M. Managerial cognitive capabilities, organizational capacity for change, and performance: The moderating effect of social capital. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1843310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rismansyah, A.M.; Hanafi, A.; Yu, L. Readiness for organizational change. Av. Econ. Manag. Res. 2021, 210, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, A.; Frankish, J.; Roberts, R.G.; Storey, D.J. Growth paths and survival chances: An application of Gambler’s Ruin theory. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M.; Korosteleva, J. Cultural diversity and knowledge in explaining entrepreneurship in European cities. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 56, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, D. Estimating Fully Observed Recursive Mixed-Process Models with Cmp. CGD. SSRN Working Paper 1392466. 2009. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1392466 (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Burnes, B. The Origins of Lewin’s Three-Step Model of Change. J. Appl. Rafferty Behav. Sci. 2020, 56, 32–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, A.E.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Armenakis, A.A. Change Readiness: A Multilevel Review. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 110–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Q.A.M.; Kassim, R.M.; Raju, V.; Tahitah, A.A.; Ameen, A.A.; Abdulrab, M. Factors affecting individual readiness for change: A conceptual framework. Int. J. Manag. Hum. Sci. (IJMHS) 2018, 2, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Meliyanti. Readiness For Change The Case of Performance Management In The Ministry of National Rducation, Indonesia; University of Canberra: Canberra, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, G.; Kirsch, J.; Merk, S.; Lightfoot, J. Relationship of organizational culture and readiness for change to employee commitment to the organization. J. Nurs. Adm. 2000, 30, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, K. From persistence to pursuit: A longitudinal examination of momentum during the early stages of strategic change. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.; Hong, A.J. Development and validation of a readiness for organizational change scale. Sage Open 2023, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blichfeldt, H.; Faullant, R. Performance effects of digital technology adoption and product & service innovation—A process-industry perspective. Technovation 2021, 105, 102275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.K.; Lauricella, T.K.; Van Fossen, J.A.; Riley, S.J. Creating energy for change: The role of changes in perceived leadership support on commitment to an organizational change initiative. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2021, 57, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, A.; Patra, S.; Chatterjee, D. Impact of culture on organizational readiness to change: Context of bank M&A. Benchmarking: Int. J. 2021, 28, 1503–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawati, E.P.; Widoatmodjo, S. Readiness for organizational change: Workplace and individual factors at PT TBK (JV company). Asian J. Soc. Humanit. 2023, 2, 1917–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Beliski, M. Towards an entrepreneurial ecosystem typology for regional economic development: The role of creative class and entrepreneurship. Reg. Stud. 2021, 55, 735–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.D.; Joe, G.W.; Rowan-Szal, G.A. Linking the elements of change: Program and client responses to innovation. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2007, 33, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menyhért, B. Energy poverty in the European Union. The art of kaleidoscopic measurement. Energy Policy 2024, 190, 114160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapsikevicius, J.; Bruneckiene, J.; Lukauskas, M.; Mikalonis, S. The Impact of Economic Freedom on Economic and Environmental Performance: Evidence from European Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenova, I. Relation between organizational capacity for change and readiness for change. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romadona, M.R. Organizational Readiness to Change in Research Institute Case Studies. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Bangkok, Thailand, 5–7 March 2019; Available online: http://www.ieomsociety.org/ieom2019/papers/527.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Czemiel-Grzybowska, W. Conceptualization and Maping of Predictors of technological Entrepreneurship Growth in a Changing Economic Environment (COVID-19) from the Polish Energy Sector. Energies 2022, 15, 6543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowronek-Mielczarek, A.; Czemiel-Grzybowska, W. Entrepreneurship research in the Poland. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2015, 23, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walicka, M.; Czemiel-Grzybowska, W.; Żemigała, M. Technology entrepreneurship—State of the art and future challenges. Eurasian J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 3, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak-Mrozek, M.; Czemiel-Grzybowska, W.; Pavlakova-Docekalova, M.; Thompson, C. Sustainable Development of Smart Cities Through Municipal Waste Incinerators: The Examples of AI in Technological Entrepreneurship. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2024; after review. [Google Scholar]

- Czemiel-Grzybowska, W. Trendy rozwoju zrównoważonej przedsiębiorczości technologicznej opartej na sztucznej inteligencji. Akad. Zarządzania 2023, 7, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnéguy, E.; Ohana, M.; Stinglhamber, F. Overall justice, perceived organizational support and readiness for change: The moderating role of perceived organizational competence. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2020, 33, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyrek, M.; Cyrek, P.; Bieńkowska-Gołasa, W.; Gołasa, P. The Convergence of Energy Poverty across Countries in the European Union. Energies 2024, 17, 4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Survival (0.1) * | Survival (0.05) ** | High Growth (0.1) * | High Growth (0.05) ** | Net Entry (0.1) * | Net Entry (0.05) ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived appropriateness of the proposed change (initial digital readiness) | 0.044 | 0.109 | −0.001 (0.00) | −0.001 (0.00) | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| Perceived management support for the proposed change (initial management readiness) | 0.109 | 0.208 | −0.001 (0.00) | −0.001 (0.00) | 0.004 | −0.001 (0.00) |

| Perceived personal capability and personal benefit to implement the proposed change (initial operational readiness) | 0.113 | 0.126 | −0.001 (0.00) | −0.001 (0.00) | 0.001 | −0.025 |

| Determinants | PGE (Polska Grupa Energetyczna) | Tauron Polska Energia | Energa (Grupa Orlen) | Enea | Grupa Azoty (Energy Segment) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Readiness Level | High. PGE demonstrates a mature management structure and a strong readiness to invest in renewable energy technologies and digitalize its operations. | Moderate. Tauron is undertaking innovative programs and gradually enhancing investments in new technologies; however, the organizational structure necessitates greater flexibility. | High. Energa, as part of the Orlen Group, possesses robust financial support and access to resources, enabling investments in pioneering technological solutions. | Average. Enea is interested in investing in new technologies; however, limited resources may affect the pace and scope of the implemented changes. | High. Grupa Azoty actively invests in research and development and collaborates with academic institutions, which enhances its readiness to implement advanced solutions. |

| Challenges | Key challenges include ensuring compliance with stringent EU regulations and attracting skilled employees specializing in advanced technologies. | Regulatory barriers and protracted decision-making processes hinder the pace of development. Additionally, adapting technology to meet the needs of a large and diverse customer base presents a significant challenge. | The primary challenges include the integration of innovative projects with existing systems and the management of risks associated with substantial investments in the development of smart grid networks. | The lack of sufficient funds and qualified personnel hampers the implementation of innovations. Additionally, there is a need to enhance efficiency in resource management. | A significant challenge lies in the high costs associated with low-emission technologies and the need to integrate energy management systems within the company’s extensive structure. |

| Success Factors | The ability to establish partnerships with research institutions and access to European funding, which supports the development of projects in renewable energy and energy storage. | Investments in digital transformation, which enhance operational efficiency and enable more accurate demand forecasting, as well as the development of renewable energy infrastructure, including wind power plants. | Partnerships with industry leaders in technology and the development of smart grids and energy management systems support the optimization of energy distribution and enhance efficiency. | Focusing on infrastructure modernization and the development of monitoring and management systems facilitates better demand management and minimizes energy losses. | Access to funding and international collaboration facilitate the development of pilot projects in low-emission technologies and energy storage while also supporting the achievement of established climate goals. |

| Area | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Assessment of Readiness | Regularly conduct assessments of organizational readiness to identify weaknesses and potencial challenges. |

| Culture of Innovation | Foster an environment conductive to innovation by encouraging creativity, rewarding new ideas, and being open to change. |

| Emploee Development | Invest in training programs focusing on new techilogies and change management. |

| Technology integration | Strategiclly plan the integration of new technologies with existing systems to improve operational efficiency. |

| Change Management | Implement formal change management processes to facilitate smoth transitions to new technological solutions. |

| Technological Partnerships | Built strategic partnerships with technology firms to leverage their expertise and experience. |

| Organizational Flexibility | Design organizational structures that enable rapid adaptation to changing market and technological conditions. |

| Risk Management | Develop risk management plans to mitigate negatice impacts associated with the adoption of new technologies. |

| Communication and Feedback | Establish systems for regular communication and feedback, allowing employees to share their idea and experiences with innovations. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Czemiel-Grzybowska, W.; Bąkowski, M.; Forfa, M. Overcoming the Challenge of Exploration: Organizational Readiness of Technology Entrepreneurship on the Background of Energy Climate Nexus. Energies 2024, 17, 5999. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17235999

Czemiel-Grzybowska W, Bąkowski M, Forfa M. Overcoming the Challenge of Exploration: Organizational Readiness of Technology Entrepreneurship on the Background of Energy Climate Nexus. Energies. 2024; 17(23):5999. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17235999

Chicago/Turabian StyleCzemiel-Grzybowska, Wioletta, Michał Bąkowski, and Magdalena Forfa. 2024. "Overcoming the Challenge of Exploration: Organizational Readiness of Technology Entrepreneurship on the Background of Energy Climate Nexus" Energies 17, no. 23: 5999. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17235999

APA StyleCzemiel-Grzybowska, W., Bąkowski, M., & Forfa, M. (2024). Overcoming the Challenge of Exploration: Organizational Readiness of Technology Entrepreneurship on the Background of Energy Climate Nexus. Energies, 17(23), 5999. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17235999