Abstract

Hydrothermal liquefaction of solid waste has been gaining more and more attention over the last few years. However, the properties of the HTL product, i.e., biocrude, are limiting its direct utilization. As a result, HTL biocrude upgrading is essential to improve its quality. The main objective of the current research is to study the hydrotreatment stabilization of HTL biocrude, produced from spent coffee grounds, utilizing commercial hydrotreated catalysts, and also to investigate the integration of the stabilized biocrude into a light cycle oil (LCO) hydrotreatment plant for coprocessing to target hybrid fuel production. The results have shown that hydrotreatment is a very promising technology that can successfully remove the oxygen content from raw biocrude by hydrodeoxygenation, decarbonylation and decarboxylation reactions, leading to a stabilized product. The stabilized product can be easily blended with the LCO stream of a typical refinery, leading to the production of jet and diesel boiling range hydrocarbons, favoring at the same time the hydrogen consumption of the process. The findings of this manuscript set the basis for future research targeting the production of renewable advanced biofuels from HTL biocrude from municipal waste.

1. Introduction

The rise in population density, economic advancement, and the expanding accessibility of products and services have introduced a continual challenge for the handling and disposal of urban solid waste. The term solid waste refers to any discarded or unwanted material, including various items like paper, plastics, glass and food wastes. Waste from coffee processing is a good example of food waste. The term coffee is associated with a broad variety of coffee processing products. The processing of coffee consists of two phases. In the first phase, the fruits from coffee are dehulled and dried, leading to a product called green coffee beans. The waste from this first step includes coffee husks, pulp and low-quality coffee beans. The second phase encompasses the stages involved in producing roasted and soluble coffee. The primary solid residue of the second step is spent coffee grounds from soluble coffee production. Spent coffee grounds (SCG) constitute the largest waste stream produced during coffee beverage preparation and instant coffee manufacturing, estimated at a total annual volume of 60 million tons worldwide [1]. Such substantial quantities underscore the importance of improving and repurposing this waste using effective approaches to fit a circular economy. One approach is the production of advanced biofuels [2].

Hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) is an advanced thermochemical technology with significant potential for biofuel production due to its feedstock variability, as it can handle both wet and dry feedstocks at various operating temperatures ranging from 523 to 723 K and pressures from 10 to 35 MPa [3]. Some typical examples of bio-based and waste feedstock are woody biomass [4], industrial waste, food waste, swine manure, algae, arborous crops, waste from the forestry industry, etc. [5]. As a result, HTL can also be easily applied in processing spent coffee grounds, resulting in a product called HTL biocrude. Although HTL is an easy process, the resulting product cannot be used as a drop-in fuel due to its low quality [6,7]. To that aim, hydroprocessing technology is playing a vital role for HTL biocrude upgrading [8].

The aim of hydroprocessing is to remove the oxygen content from the HTL biocrude using hydrodeoxygenation, decarbonylation and decarboxylation reactions [9]. The final product is a two-phase product consisting of the organic phase, which is the main stabilized biocrude product, and also from the low-value aqueous phase. Furthermore, light gas hydrocarbons are also produced such as methane, propane, ethane, etc. The organic product can be further upgraded via a second, more severe hydrotreatment step to drop in advanced biofuels [10] or can be integrated in a typical refinery as an intermediate stream for coprocessing with fossil streams, leading to hybrid fuel production [11]. HTL is a state-of-the-art technology for biocrude production; thus, there are very few studies that investigate the upgrading of HTL biocrude via hydrodeoxygenation; as a result, there are many challenges that still have to be addressed. The operating parameters of hydrodeoxygenation are very important because they affect the properties of the resulting organic product as well as the operating process costs, due to variations in hydrogen consumption [8]. Furthermore, the proper catalyst is important as it strongly influences the process duration. It was observed that the hydrodeoxygenation of HTL biocrude with commercial hydrotreating catalysts reduces the life of the catalysts due to coke formation on the active sites [12]. In addition, as the biocrude is characterized by high viscosity, the use of larger-diameter piping and heat tracing on the typical hydrotreatment plants is important, while the existence of minerals in the biocrude causes catalyst deactivation. Based on all the above, it is easy to see that further research is necessary for the optimization of HTL biocrude stabilization by hydrotreatment.

To that aim, the role of this research is, firstly, to investigate the mild hydrotreatment stabilization of an HTL biocrude, produced from spent coffee grounds, and, secondly, to investigate the integration of the stabilized biocrude into a light cycle oil (LCO) refinery stream. For the first phase of the research, the HTL biocrude was hydrotreated utilizing commercial catalysts and the effect of reaction temperature and hydrogen-to-oil ratio on product quality and process efficiency was studied to fill the gap in the literature concerning the biocrude stabilization process. In the second phase of the research, the stabilized biocrude was blended with LCO in two different blends (10 and 20% v/v stabilized biocrude) to investigate the effect of the stabilized biocrude on catalyst life and product quality during coprocessing, targeting advanced fuel production. As a result, this research will form the basis in terms of biocrude stabilization and integration of upgraded biocrude on a refinery LCO hydrotreatment plant.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scope

The main scope of this study is, firstly, to examine the stabilization process of an HTL biocrude and, secondly, to study the integration of the stabilized biocrude into LCO hydrotreatment by coprocessing for advanced fuel production. To that aim, in the first step of the current research, the mild hydrotreatment upgrading of an HTL biocrude oil was investigated to study the effect of the hydrotreatment operating parameters on product quality and hydrogen consumption. In the second step, integration of the stabilized HTL biocrude into the LCO hydrotreatment plant was explored for advanced fuel production. LCO consists of polar molecules like aromatics; therefore, based on a miscibility screening study [13], it was selected as the most suitable petroleum candidate for coprocessing with the stabilized biocrude. Furthermore, the upgrading of LCO is not profitable, as it is a low-quality refinery stream; as a result, mixing biocrude with LCO for coprocessing may better justify the cost of LCO upgrading [14]. To that aim, two different blends were tested (90/10 and 80/20% v/v—LCO/HDT biocrude) by coprocessing in order to investigate the catalyst deactivation and product quality. All experiments were performed at the CERTH.

2.2. Feeds

For this study, an HTL biocrude produced from hydrothermal liquefaction of spent coffee grounds was explored. According to the HTL biocrude properties presented in Table 1, the HTL biocrude has higher density compared to the standards of transportation fuels. Furthermore, the oxygen content is high, approximately 15.7 wt%, showing that the HTL biocrude consists of various oxygenate compounds. Even though the HTL biocrude’s initial sulfur content was 700 wppm, dimethyl-disulfide (DMDS) was inserted to the feed to supplement the sulfur content up to 1300 wppm, required by the sulfided catalyst employed for the hydrotreatment (in industrial-scale applications, DMDS can be replaced by the hydrogen sulfide from the off-gas from the hydrotreating processes [15]). In addition, the heating value is lower (35.3 MJ/kg) compared to the transportation fuel standards (EN 590 for diesel > 43.8 MJ/kg, EN 228 for gasoline > 34.84 MJ/kg, EN 15940 for HVO > 44 MJ/kg and Jet A for jet fuel > 42.8 MJ/kg).

Table 1.

Properties of raw HTL biocrude, light cycle oil (LCO) and their blends.

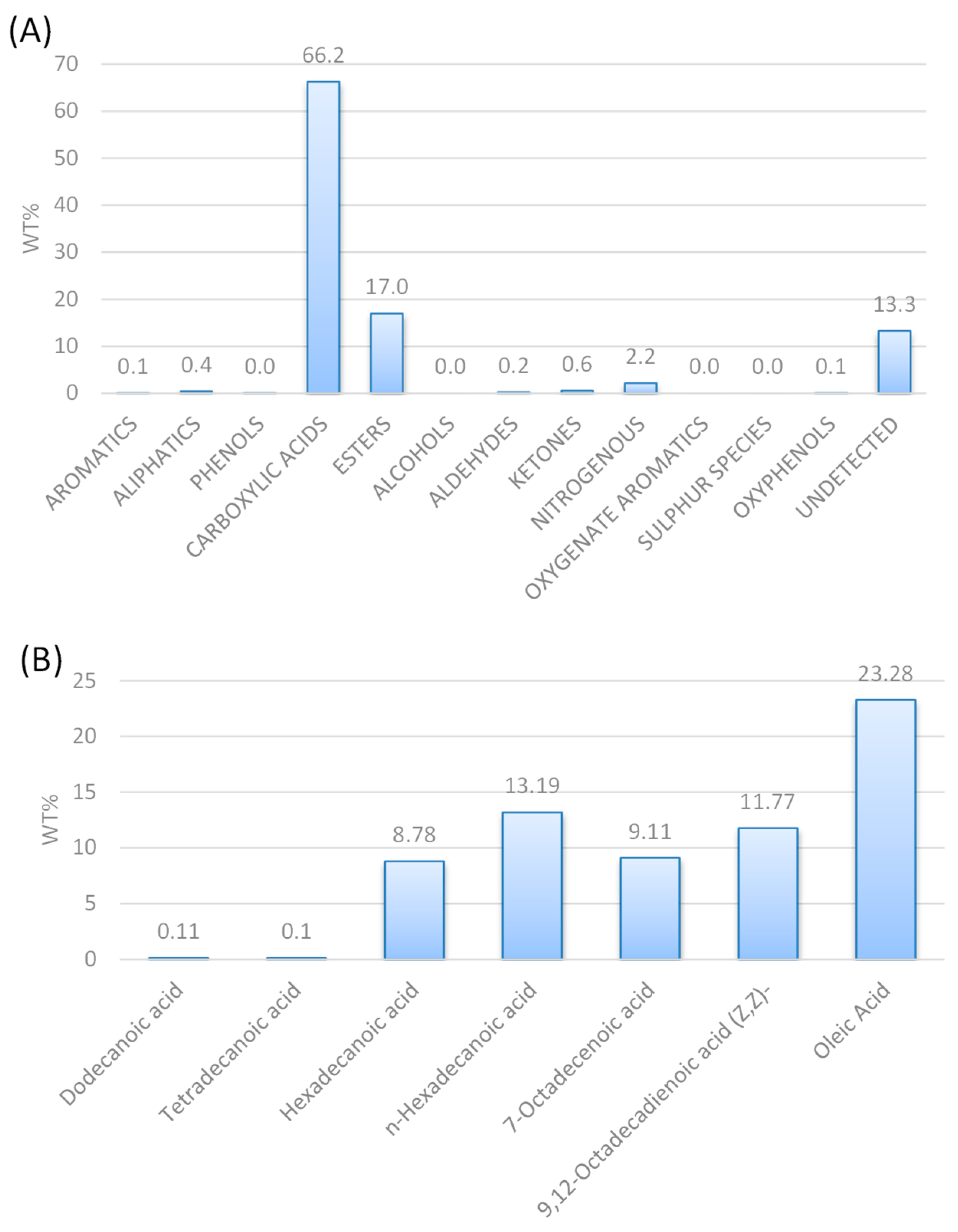

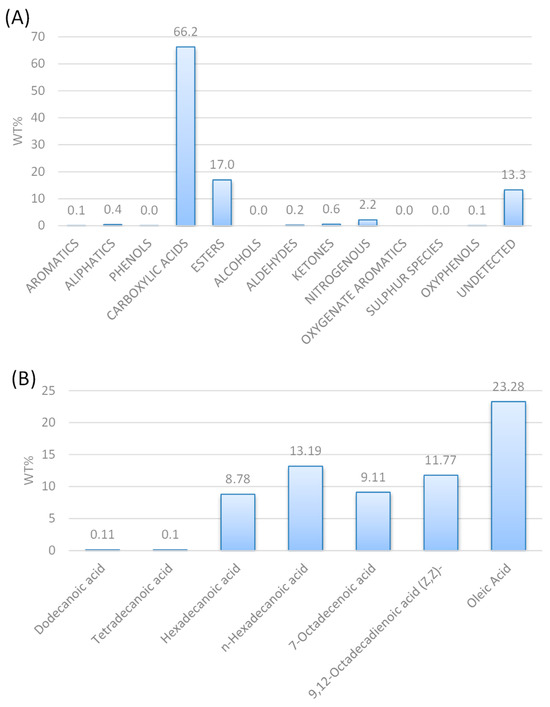

According to the GC-MS chromatograph analysis of the HTL biocrude (Figure 1A), it consists of 66.2 wt% carboxylic acids, 17.0 wt% esters, 2.2 wt% nitrogenous and some traces of aromatics, aliphatic aldehydes, ketones, and oxyphenols. As the carboxylic acids are more than 50 wt%, the composition of the carboxylic acids was further analyzed (Figure 1B), indicating that it consists mainly of oleic acid (23.28 wt%), n-hexadecanoic acid or palmitic acid (C16:0, 13.19 wt%), 9,12-octadecanoic acid or linoleic acid (C18:2, 11.77 wt%), 7-octadecanoic acid (C18:1, 9.11 wt%) and hexadecenoic acid or palmitoleic acid (C16:1, 8.78 wt%).

Figure 1.

GC-MS analysis of HTL biocrude oil (A) shows the composition of the feed and (B) shows the carboxylic acid concentration.

2.3. Catalysts

The aim of this manuscript is, firstly, to study the mild hydrotreatment upgrading of the initial HTL biocrude and, secondly, to investigate the integration of the stabilized HTL biocrude on LCO hydrotreatment via co-hydroprocessing. To that aim, in the first step, a commercial hydrotreating catalyst NiMo/Al2O3 was utilized. NiMo catalysts are widespread catalysts that are used by refineries for the upgrading of petroleum streams; however, they have also been tested for upgrading different biocrudes from microalgae [10,16], animal carcass [17], sewage sludge [6], food wastes [18], solid wastes [11], etc. The catalyst was blended with a demetallization catalyst featuring moderate hydrodesulfurization (HDS) activity at a 7.1 v/v ratio (demetallization/HDO catalyst) to achieve the desired Liquid Hourly Space Velocity (LHSV). This approach ensured thorough dispersion throughout the reactor, supporting efficient heat and mass transfer. However, more details about the catalysts cannot be provided due to the confidentiality restrictions, as they are commercial catalysts. The activation procedure of the catalysts was performed based on the instructions of the catalyst provider.

For the coprocessing experiment (LCO + stabilized HTL biocrude), the same NiMo/Al2O3 catalyst was utilized in combination with the same demetallization catalyst with a moderate hydrodesulfurization (HDS) activity at a ratio of 5.6 v/v demetalization/HDO catalyst.

2.4. Analysis

Products were collected on a daily basis and were analyzed in the analytical laboratory of CERTH. The liquid products were analyzed offline using an existing analytical infrastructure. The gaseous products were analyzed online via an online GC 7890 Agilent analyzer and 5975C mass spectroscopy analyzer (Agilent, St. Clara, CA, USA) to ensure high accuracy on hydrogen consumption calculation. The method for the hydrogen consumption calculation is deeply described in the authors’ previous work [8]. In the case of the liquid samples, the density was determined via ASTM D-4052 [19], while the distillation curve was estimated via ASTM D-7169 [20]. Hydrogen and carbon content were determined using the LECO ASTM D-5291 [21] method. The sulfur content was determined by an XRFS analyzer via ASTM D-4294 [22] and the nitrogen content via ASTM D4629 [23]. The oxygen concentration was indirectly calculated from the stoichiometric analysis (C, H) and the measurement of the sulfur and nitrogen content, assuming a negligible concentration of all the other elements in the liquid samples. The water content was found via ASTM D-6304 [24] and ASTM E-203 [25] depending on the type of sample. The total acid number (TAN) was calculated via the ASTM D-664 [26]. Kinematic viscosity was determined via ASTM D445 [27], cetane index on the products was measured via the ASTM D-976 [28], pour point via ASTM D-97 [29] and micro carbon residue (MCR) via ASTM D4530 [30]. More details about the analytical instrument equipment can be found in [8].

The calculation of the high heating value (HHV) was based on Equation (1) provided by Channiwalla and Parikh, 2002 [31]:

where C, H, O, N, and S, represent the corresponding elemental wt% composition on a dry basis.

2.5. Testing Infrastructure

All hydroprocessing tests (including first mild hydrotreatment of HTL biocrude and co-hydroprocessing of the stabilized biocrude and LCO blends) were performed in a continuous operation, TRL 3 (Technology Readiness Level) hydrotreatment plant of the Chemical Process & Energy Resources Institute (CPERI) of CERTH. The current plant is equipped with a high-flexibility system and has the ability to provide important testing data that can be used for the scaling-up of the process to a commercial level. More details of the plant can be found in [32].

2.6. Experimental Procedure

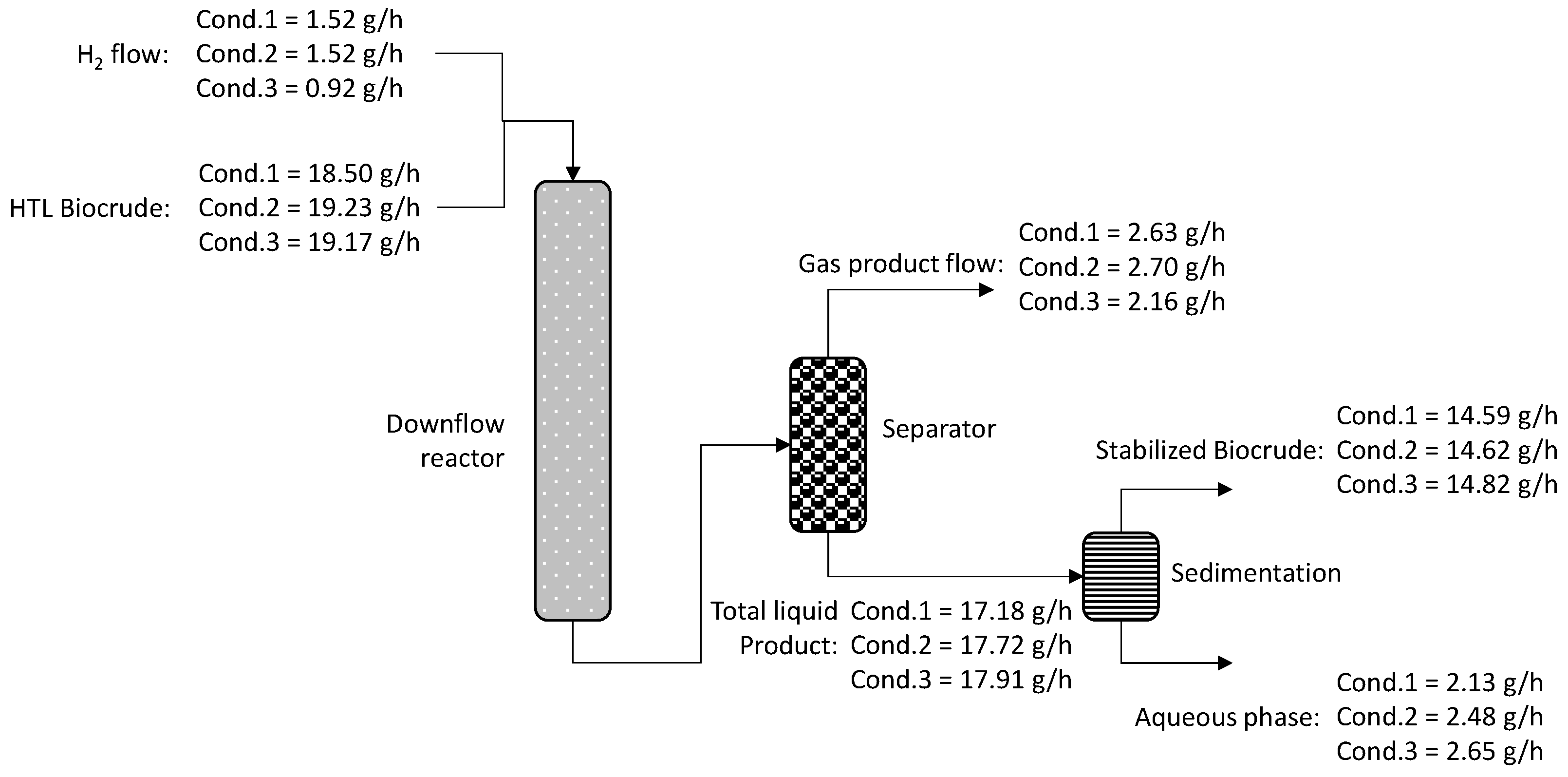

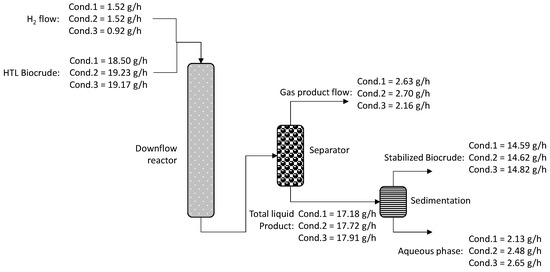

On the first step of the current study, the mild upgrading of an HTL biocrude was investigated via hydrotreatment, targeting to stabilize the biocrude. During the current step, the effect of the hydrotreatment operating conditions on product quality and process performance was explored. To that purpose, three conditions were tested, targeting to examine two different hydrotreating temperatures (603 K and 633 K) and two hydrogen-to-oil ratios (3000 scfb and 5000 scfb). The experimental protocol is presented in Table 2. The operating window was selected based on a detailed literature screening on pyrolysis bio-oil and HTL biocrude hydrotreatment [18,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. The first and second conditions lasted three days on stream (DOS) each, while the third condition lasted 2 days on stream due to the limited feedstock availability. Daily liquid samples were collected in order to measure the density and sulfur content, while, on the sample of the last day of each condition, more analyses were performed, including the mass balance and hydrogen consumption calculations. All conditions were explored via one dedicative run that had a total duration of 8 consecutive days.

Table 2.

Hydrotreatment operating window for biocrude stabilization.

At the end of the run, all liquid products were collected and blended together creating one total liquid product that was used on the next phase of the research. Thus, at the next step, the co-hydroprocessing of the total organic liquid product (stabilized HTL biocrude) collected from the first run was investigated in blends with LCO. The choice of LCO was based on an author’s preceding research [13,32,43,44], which showed that LCO consists of polar molecules like aromatics, similarly to the stabilized HTL biocrude and, as a result, it shares similar challenges as a feedstock for advanced fuel production and also presents very good miscibility with the upgraded HTL biocrude. The addition even of 10% per volume of upgraded HTL biocrude in neat LCO caused a color change to the sample, as the upgraded biocrude is darker than LCO. The properties of pure LCO as well as of the blends are presented in Table 1. More details about the effect of the stabilized biocrude in LCO at 10 and 20% volume will be discussed later in the results in Section 3.2.

The operating window for co-hydroprocessing is the same with the operation of a typical refinery, which is the product potential end-user [32]. The parameters of pressure, LHSV and H2/oil ratio remained constant, while the reactor temperature was gradually increased during the experiment (593–663 K) in order to keep steady the sulfur content of the products. The aim was to investigate how the 10% and 20% v/v of the stabilized biocrude integration influence the HDS activity of the catalyst during hydrotreatment of LCO. The stabilized biocrude insertion in LCO negatively influences the catalyst HDS efficiency. In order to counterbalance this negative influence, the temperature was gradually increased to maintain the product sulfur content at constant levels, similar to that of the reference case with neat LCO. Finally, during the coprocessing experiment, the reactor pressure was kept constant at 6.9 MPa, LHSV at 1 h−1 and H2/liquid feed ratio at 3000 scfb.

3. Results

3.1. Stabilization of HTL Biocrude

3.1.1. Oxygen Removal

As was already mentioned, the first part of the current investigation is the stabilization of an HTL biocrude. During this investigation, the effect of reaction temperature and hydrogen-to-biocrude ratio was examined by testing two temperatures and two H2/biocrude ratios. According to the properties of the HTL biocrude, it has high oxygen content (15.7 wt%), which creates miscibility problems when this feedstock is blended with petroleum streams. Thus, the main target of hydrotreatment is to fully deoxygenate the biocrude via hydrodeoxygenation, decarbonylation and decarboxylation reactions, resulting in a double-phase product consisting of the organic liquid, which is the main liquid product (stabilized biocrude), and the aqueous phase, which most of the time consists mainly of water [10]. As a result, after the first hydrotreatment step, the resulting product was a two-phase liquid where the second aqueous phase was removed via gravity. Measurement of the water content from the aqueous phase has shown that it consists of 99 wt% water; as a result, no further analysis was performed. The remaining organic phase, which, from now on, will be called “stabilized biocrude”, from the three conditions was fully analyzed. The properties from the three stabilized biocrudes (one from each condition) are presented in Table 3. From the results, it is observed that the oxygen content was reduced almost to zero in all tested conditions. This result confirms the effectiveness of the hydrotreatment on removing the oxygen from the neat biocrude. More specifically, the rate of oxygen removal is 97.5%, 98.6% and 93.9% for conditions 1, 2 and 3, respectively. The rate of oxygen removal was calculated from the oxygen content of the feed and products on a dry basis (weight percent) based on Equation 2 below. Complete deoxygenation was also observed by Haider et al. [10], who investigated the hydrotreatment of biocrude from spirulina. Furthermore, the sulfur content was strongly reduced from the initial biocrude (1300 wppm with the addition of DMDS) to less than 250 wppm, with the lowest number in condition 1 (160 wppm). Another important observation is the increase in the heating value that was raised from 35 MJ/kg (raw biocrude) to 46 MJ/kg (stabilized biocrude), increasing in that way the quality of the stabilized biocrude in all examined conditions. A similar increase in biocrude heating value was observed by the team of Magalhaes [45] that hydrotreated an HTL biocrude from Chlorella sorokiniama microalga, with an initial biocrude heating value at 36 MJ/kg that was increased to 47 MJ/kg after the hydrotreatment process, improving in that way the quality of the biocrude. The increase in heating value is a result of the complete oxygen removal [6]. Furthermore, the viscosity was reduced from 27.7 cSt (raw biocrude) to less than 7 cSt (stabilized biocrude), which agrees with the results obtained by Kohansal et al. [11], who noticed a dramatic decrease in viscosity of biocrude after a mild hydrotreatment step. The reason for viscosity reduction is the lower heteroatom content achieved via the stabilization step, which leads to weaker intermolecular forces that improve the flow of the liquid. Furthermore, density was reduced compared to initial biocrude, which confirms the findings of Kohansal et al. [11]. To conclude, hydrotreatment was able to improve the properties of density, viscosity, heating value and H/C ratio compared to the initial raw biocrude. Similar results were found by other studies, where an improvement in biocrude properties was observed after a first mild hydrotreatment step [6,46].

Table 3.

Properties from the final stabilized biocrude from each operating condition tested.

3.1.2. Gas Product Characterization

In order to better understand the reactions pathway from the oxygen removal, the gas products of each condition were analyzed via a GC analyzer and the results are presented in Table 4. The main reactions during hydrotreatment of the HTL biocrude are summarized below via Equations (3)–(8). Hydrodeoxygenation (Equation (3)) removes oxygen via the formation of the second aqueous phase. Decarboxylation (Equation (4)) removes the oxygen via the formation of carbon dioxide, while decarbonylation (Equation (5)) does so via the formation of carbon monoxide. However, during hydrotreatment, there is a possibility to react the produced carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide with hydrogen, leading to the formation of methane via methanation reactions (Equations (6)–(8)), but carbon dioxide can also react with the hydrogen, leading to the formation of carbon monoxide and water via water gas shift reactions (Equation (9)). During the process, all these reactions take place at the same time; however, the ratio of the reactions is strongly influenced by the operating parameters of the process. The methanation reactions are strongly exothermic, which can lead to catalyst overheating and, thus, deactivation due to coke formation. As a result, methanation reactions are not preferable. In addition, the decarboxylation as well as the decarbonylation reactions are not so preferable because they are connected with carbon losses from the liquid product to the gas products. The most preferable reaction is hydrodeoxygenation, where the oxygen is removed in the form of water and, thus, there are no carbon losses in the gas products.

Table 4.

Gas product composition analysis.

According to Table 4, an increase in reaction temperature from 603 K (condition 1) to 633 K (condition 2) results in higher methane formation, enhancing in that way methanation reactions. The carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide reduced because they reacted with the hydrogen to produce methane, which led eventually to higher hydrogen consumption (see Table 3). In addition, the amount of propane increased, leading to higher carbon losses in the gas phase. Furthermore, reduction in hydrogen supply via condition 3 (lower hydrogen-to-oil ratio compared to condition 1) led to the production of higher amounts of gas hydrocarbons (methane, propane, ethane, etc.), which means higher carbon losses in the gas products. However, the hydrogen consumption reduced in condition 3 compared to 1. In addition, the sulfur content of the stabilized biocrude from condition 3 is higher compared to that obtained from condition 1. In general, during hydrotreatment of biocrude, the hydrodeoxygenation reactions are competitive to desulfurization reactions. The higher sulfur content on the stabilized biocrude of condition 3 compared to that from condition 1 confirms that the hydrogen of condition 3 is not able to cover both hydrodeoxygenation and hydrodesulfurization reactions. Thus, hydrodeoxygenation reactions consume a higher amount of hydrogen. From the above analysis, it is observed that the preferable condition is condition 1 due to the lower carbon losses on the gas phase as well as due to the average hydrogen consumption compared to conditions 2 and 3.

3.1.3. Cracking and Saturation Reactions

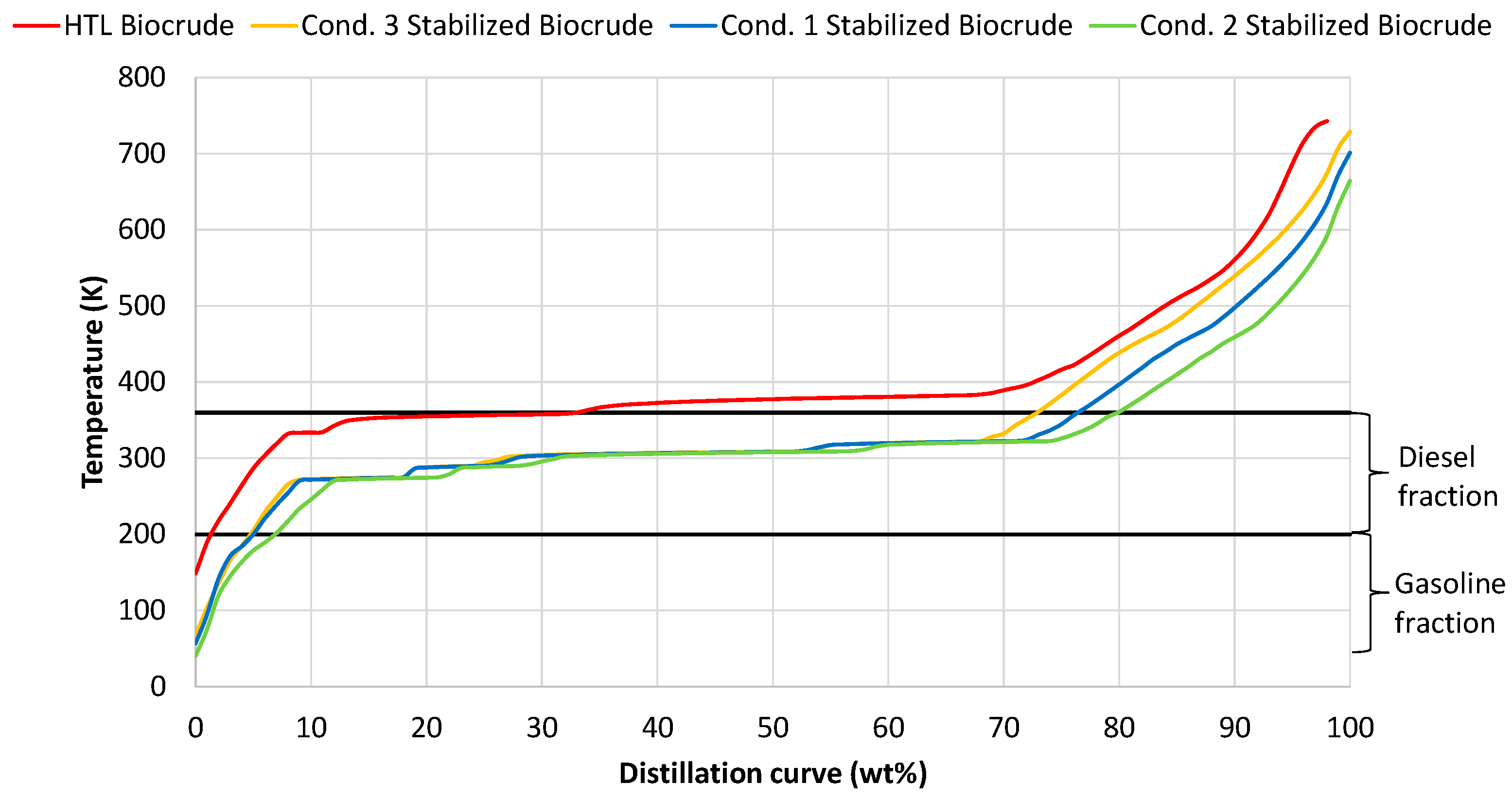

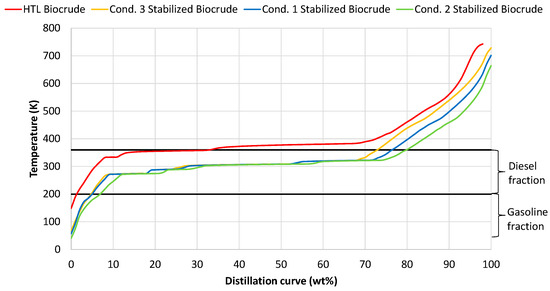

The instability of raw biocrude, is due to its heavy hydrocarbon molecules, thus hydrocracking and saturation of these heavy molecules is necessary for the stabilization of the resulting product. The raw biocrude oil consists of heavier hydrocarbons above the diesel boiling range (Figure 2); however, the stabilized products from the three conditions consists of lighter hydrocarbons inside the diesel boiling range of more than 70 wt%. These results confirm the efficiency of the catalyst cracking activity. Furthermore, it is also noticed that the operating parameters of the process do not strongly influence the size of the produced hydrocarbons as the distillation curves of the three conditions are almost similar, with small deviations above 70 wt%.

Figure 2.

Distillation curves from raw HTL biocrude and from the stabilized products from conditions 1, 2 and 3.

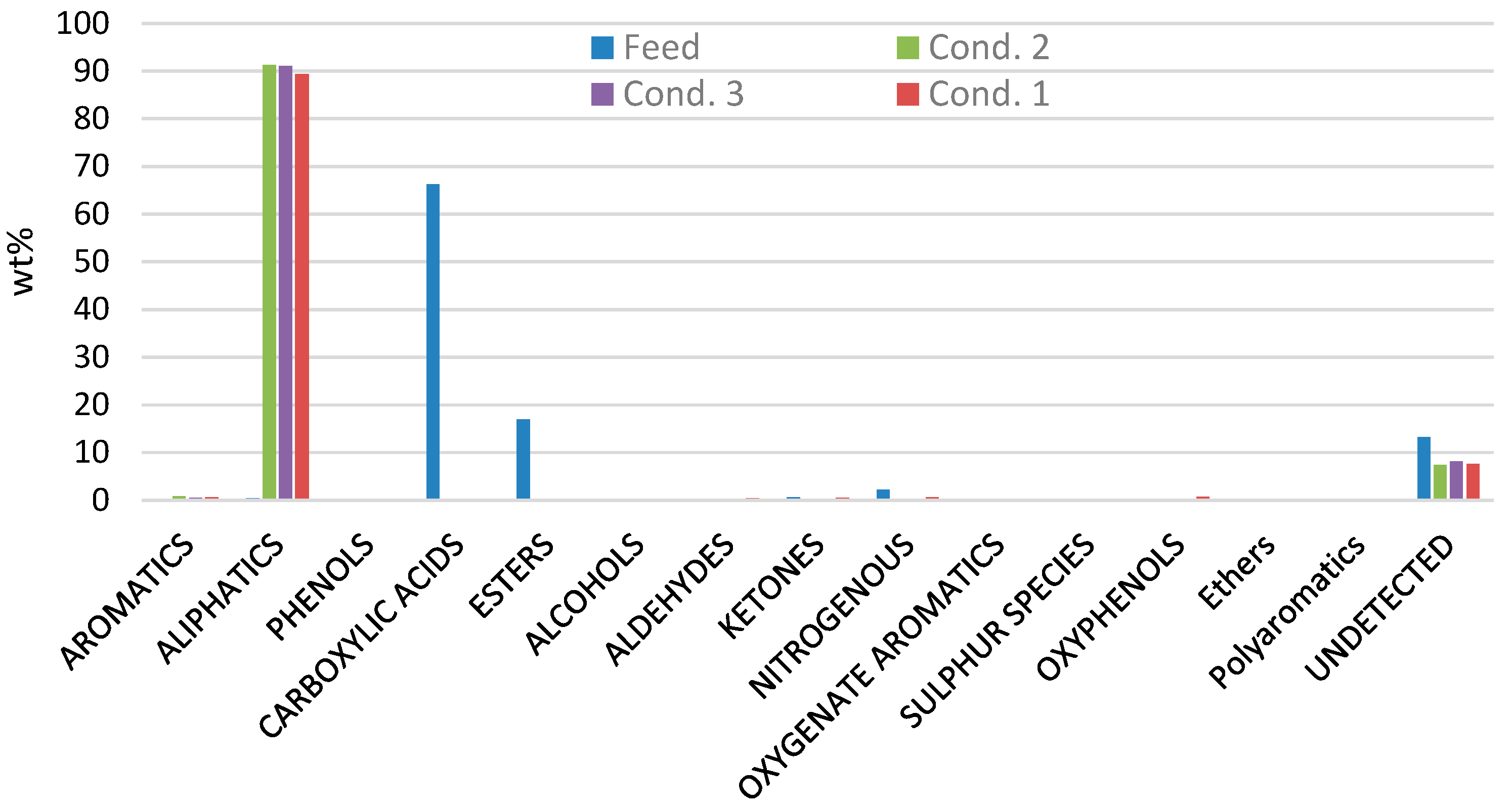

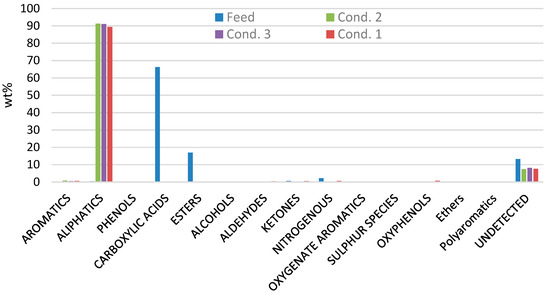

The results from the GC-MS analyzer of the raw HTL biocrude and of the stabilized products from the three tested conditions are presented in Figure 3. The results show that the raw biocrude consists mostly of carboxylic acids by 66 wt% and esters by 17 wt%. In addition, there are also some small amounts of nitrogenous species (like indoles 2.18 wt%), phenols (0.04 wt%), aromatics (0.08 wt%), aldehydes (0.2 wt%), ketones (0.6 wt%), oxyphenols (0.07 wt%) and aliphatics (0.4 wt%).

Figure 3.

GC-MS analysis from raw HTL biocrude (feed) and from the stabilized products from conditions 1, 2 and 3.

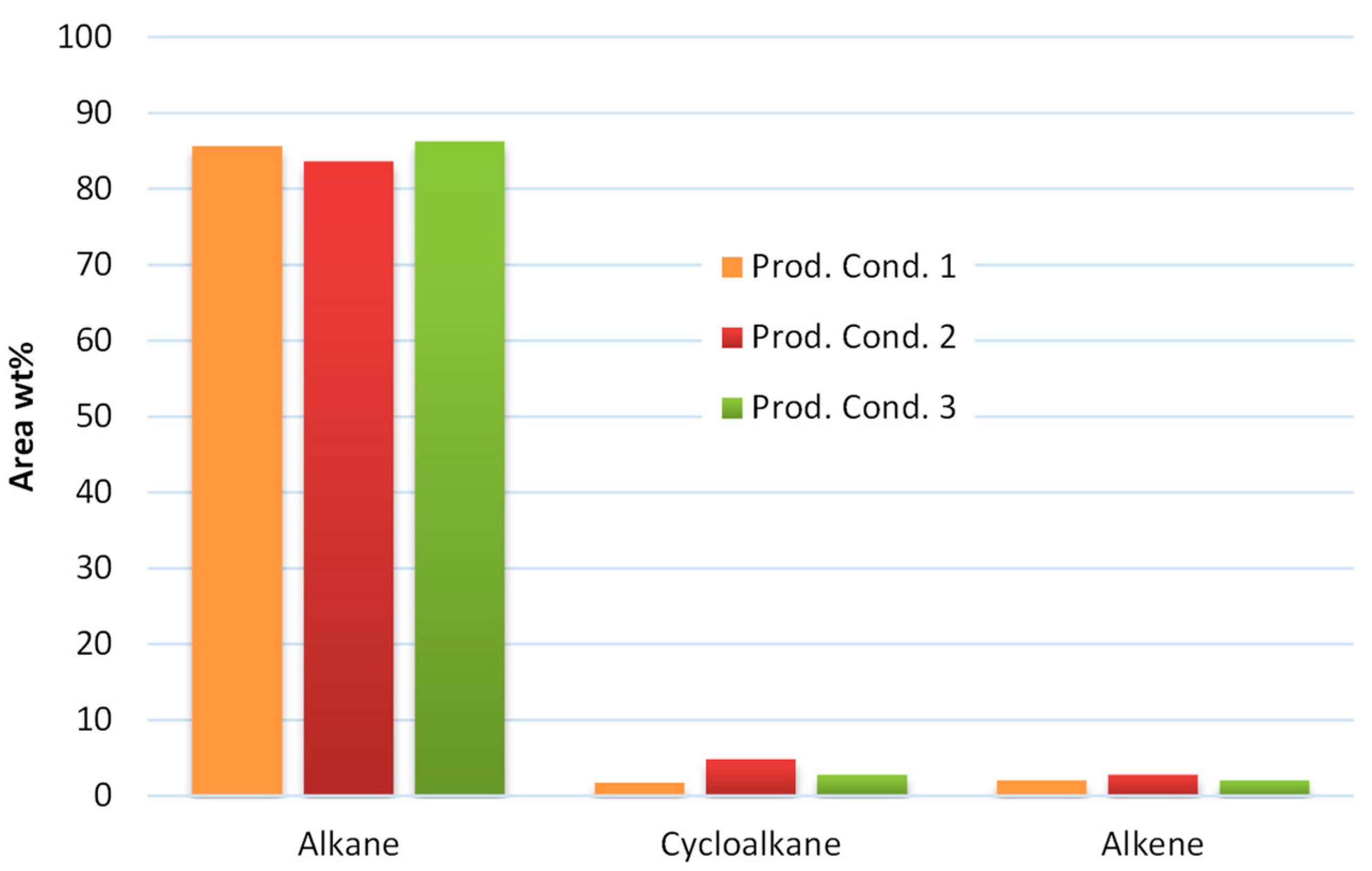

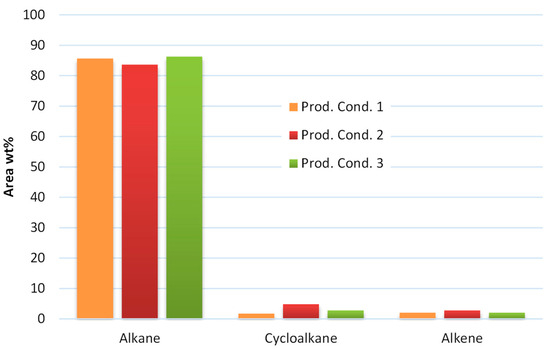

On the other hand, the stabilized products after the mild hydrotreatment step consists mainly of aliphatic hydrocarbons by >90 wt%. Aliphatic hydrocarbons are hydrocarbons based on chains of carbon atoms. More specifically, the product from condition 1 consists of 85.65 wt% alkanes, 1.74 wt% cycloalkane and 2.05 wt% alkene, the product from condition 2 consist of 83.68 wt% alkane, 4.84 wt% cycloalkane and 2.78 wt% alkene, while the product of condition 3 consists of 86.27 wt% alkane, 2.77 wt% cycloalkane and 2.09 wt% alkene as presented in Figure 4. These results show the efficiency of the hydrotreatment to transform the heavy carboxylic acids that have carbon atoms bonded to oxygen atoms by a double bond and to hydroxyl groups by a single bond to the corresponding aliphatic hydrocarbons, which are organic molecules without carbon–carbon double or triple bonds (alkane and cycloalkane). Kohansal et al. [11] also noticed the formation of alkanes, such as hexa- and octadecanes, after the hydrotreatment of biocrude from municipal solid wastes.

Figure 4.

Aliphatic hydrocarbon analysis from the products of the examined conditions.

Finally, the last parameter that was evaluated is the organic product mass yields, presented in Figure 5. Mass yields were calculated according to Equation (10) presented below. The mass yield for condition 1 is 78.8%, for condition 2 is 76.0% and for condition 3 is 77.3%. It is observed that the higher mass yields for the organic liquid product (stabilized biocrude) were achieved in condition 1. The respective hydrogen consumption for each condition is 335 NL/L feed for condition 1, 413 NL/L feed for condition 2 and 293 NL/L feed for condition 3. It is noticed that condition 1 is the preferable one as it is characterized by higher mass yields with an average hydrogen consumption. To conclude, the optimum condition from the tested ones is condition 1 as it presents higher mass yields, an average hydrogen consumption, lower carbon losses in the gas products and an organic liquid product with very good characteristics.

Figure 5.

Process mass yields.

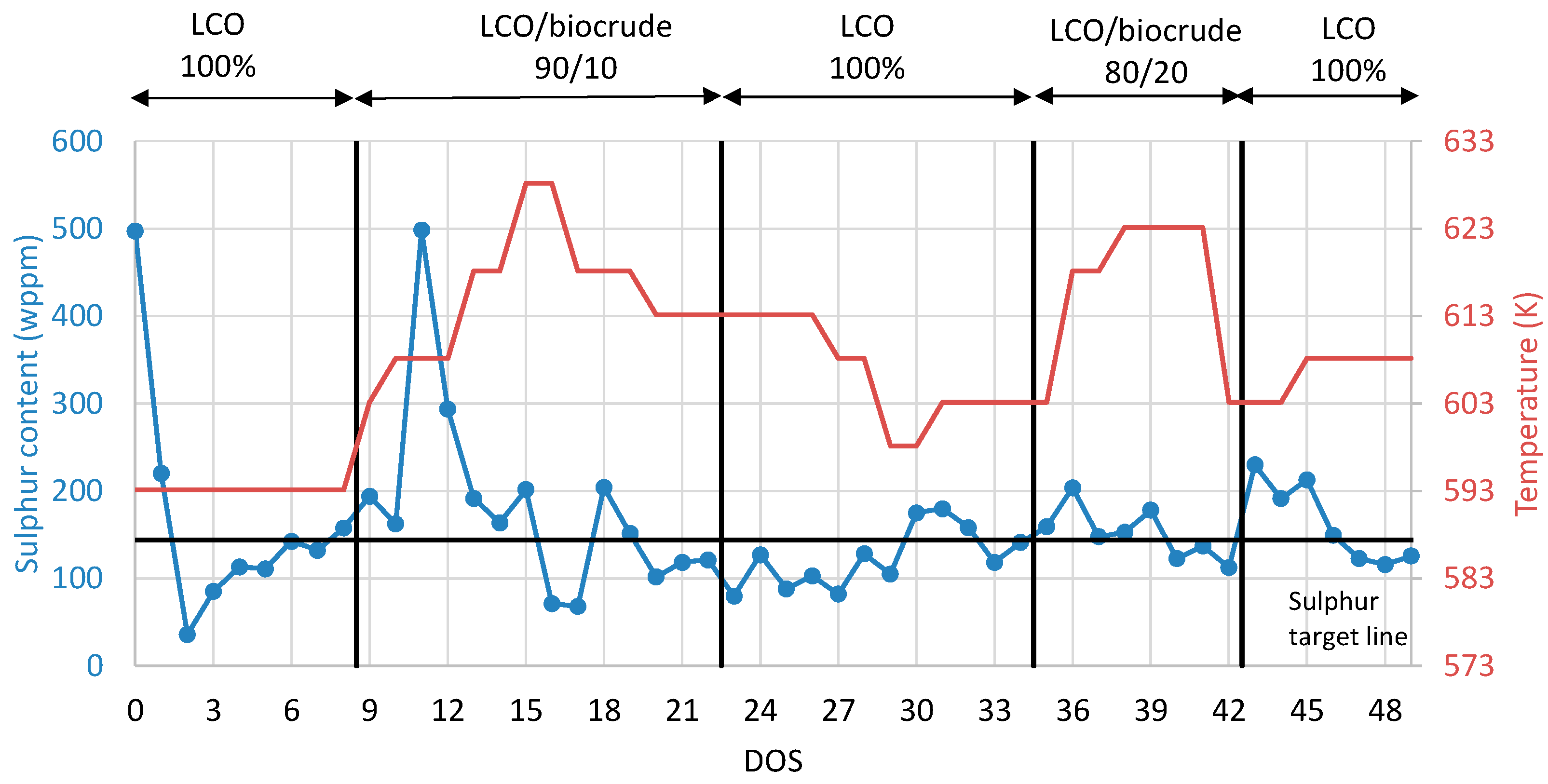

3.2. Coprocessing

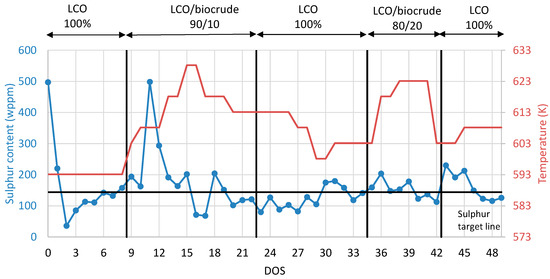

The second step is to examine the integration of the stabilized biocrude on LCO hydrotreatment process. To that aim, all organic products collected from the previous experiment of biocrude stabilization were blended, creating one total stabilized organic liquid product for the coprocessing experiment. The coprocessing testing overview of the product sulfur content variation and the corresponding reactor temperature variation are presented in Figure 6. After the presulfiding procedure, the neat LCO was inserted in the unit for nine consecutive DOS as a catalyst stabilization procedure and also as a base case. On the ninth DOS, the first blend with 10% stabilized biocrude was inserted into the pilot plant and examined for 13 days (DOS 9–22). By this approach, the influence on the HDS catalyst activity of 10% stabilized biocrude addition in LCO was studied. An increase in sulfur content in the products was observed with the addition of the stabilized biocrude; to that aim, the temperature was increased to keep the sulfur content of the product constant as close as possible to the reference scenario with the neat LCO. As a result, the temperature reached 613 K in order to achieve a product with the same sulfur content to that of the neat LCO. On DOS 22, neat LCO was inserted again in the unit in order to investigate if the HDS catalyst deactivation was permanent or temporary. The results have shown a 10 K permanent deactivation on HDS catalyst activity as, in order to achieve a product with the same sulfur content to the initial condition, the temperature was increased from 593 K to 603 K. At the next step, on DOS 34, the blend of 20%v/v stabilized biocrude and 80% v/v LCO was inserted in the unit and the same procedure was followed. After each blend with the different feeds, the LCO control condition was repeated. The permanent and temporary HDS catalyst deactivations are presented in Table 5. According to the results, the higher the stabilized biocrude content is, the higher the inhibition effect on HDS catalyst efficiency. In the case of 10% v/v of stabilized biocrude, the temporary deactivation is 20 K, while the permanent deactivation is 10 K. In the case of 20% v/v of stabilized biocrude content, the temporary deactivation is 30 K, while the permanent is 15 K.

Figure 6.

Coprocessing testing overview of product sulfur content and the corresponding reactor temperature variation during coprocessing.

Table 5.

Effect of stabilized biocrude content on catalyst HDS efficiency expressed in terms of temperature (K) needed to achieve the same sulfur removal with neat LCO (temporary and permanent HDS inhibition).

The effect of the stabilized biocrude addition in LCO hydrotreatment in terms of liquid product properties is presented in Table 6. The addition of the stabilized biocrude in LCO hydrotreatment does not strongly influence the product properties. Density in all examined cases is almost similar and close to 0.9 g/mL. Furthermore, the hydrogen and carbon content are very similar in all examined cases; hydrogen is approximately 12 wt% and carbon approximately 87.5 wt%, with very small deviations depending on the feed type. In addition, the oxygen and nitrogen content are close to detected limitations (almost zero). Cetane index is slightly increased with the addition of the stabilized biocrude, improving in that way the quality of the final fuel. TAN is zero in all examined cases, while the viscosity is not influenced by the addition of the stabilized biocrude in LCO feed.

Table 6.

Properties of products obtained from the coprocessing testing of the LCO/stabilized biocrude blends.

A very important factor during hydrotreatment is the hydrogen consumption, as it is strongly connected with the economic efficiency of the process. It is observed that the addition of the stabilized biocrude reduces hydrogen consumption, which is lower for the blends compared to neat LCO. As was deeply discussed in the previous section, stabilized biocrude mainly consists of aliphatic hydrocarbons (>90 wt%) with low sulfur content (362.1 wppm), in contrast to LCO, which consists of heavy-range hydrocarbons with high sulfur content of 2660 wppm. Thus, the addition of the stabilized biocrude reduces the sulfur content of the feed, as well as reducing the range of the heavy hydrocarbons; as a result, the hydrogen consumption during coprocessing decreases compared to the neat LCO hydrotreatment. This effect leads to economic benefits for the refinery.

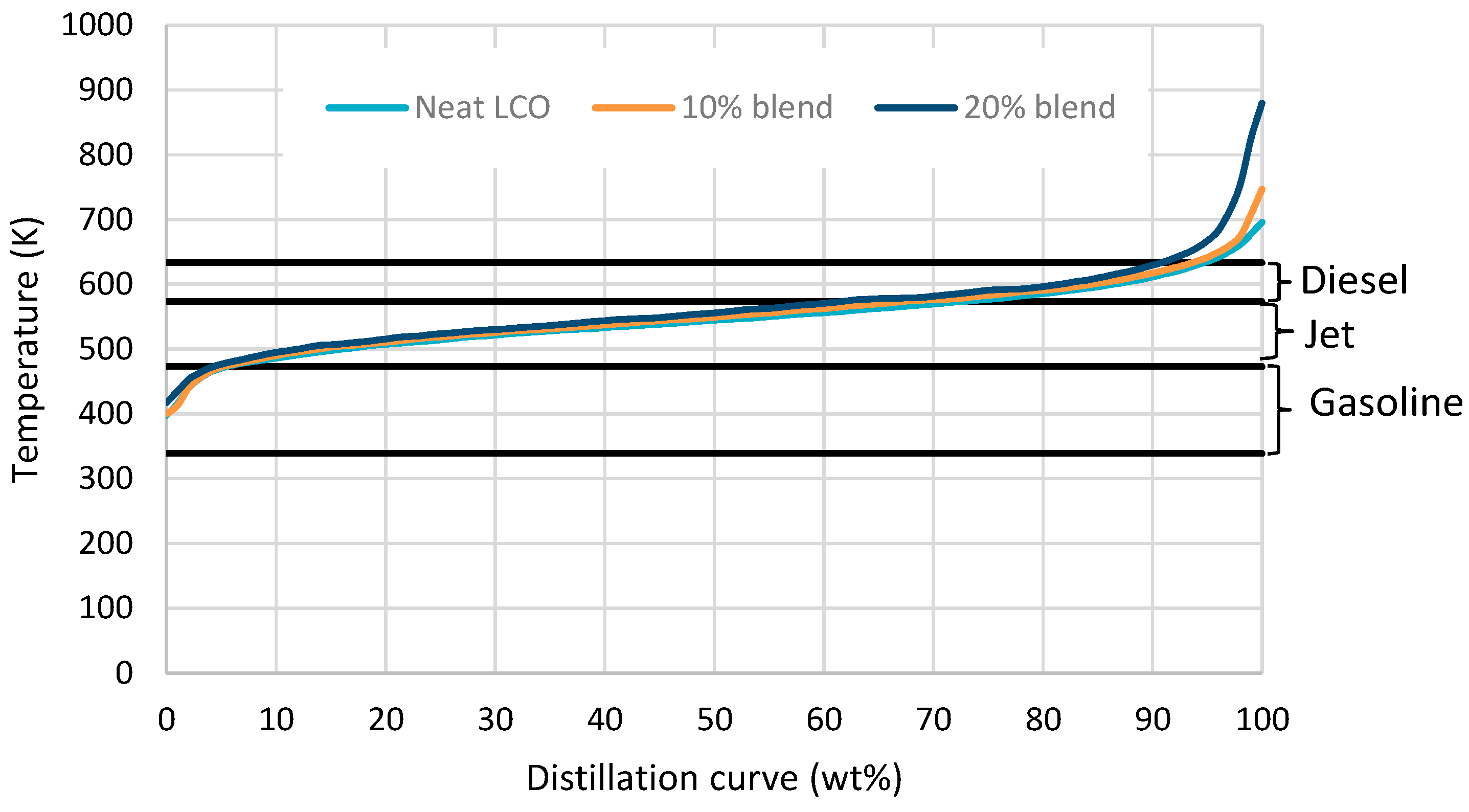

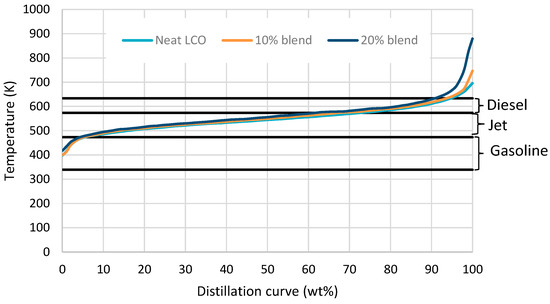

The effect of stabilized biocrude insertion in LCO in terms of hydrocarbons’ boiling range is presented in Figure 7. The results show that the addition of 10% v/v partially stabilized biocrude in LCO does not influence the hydrocarbons’ boiling range. Jet and diesel boiling-range hydrocarbons are produced with 10% addition. However, increasing the percent of the partially stabilized biocrude to 20% slightly increases the percent of the heavier-boiling-range hydrocarbons compared to the neat LCO case. Overall, the research demonstrates that incorporating a partially stabilized biocrude into an LCO hydrotreatment plant enables the production of advanced fuels, yielding liquid products with hydrocarbons in the jet and diesel boiling range.

Figure 7.

Product distillation curve from neat LCO, 10% and 20% v/v blend with stabilized biocrude.

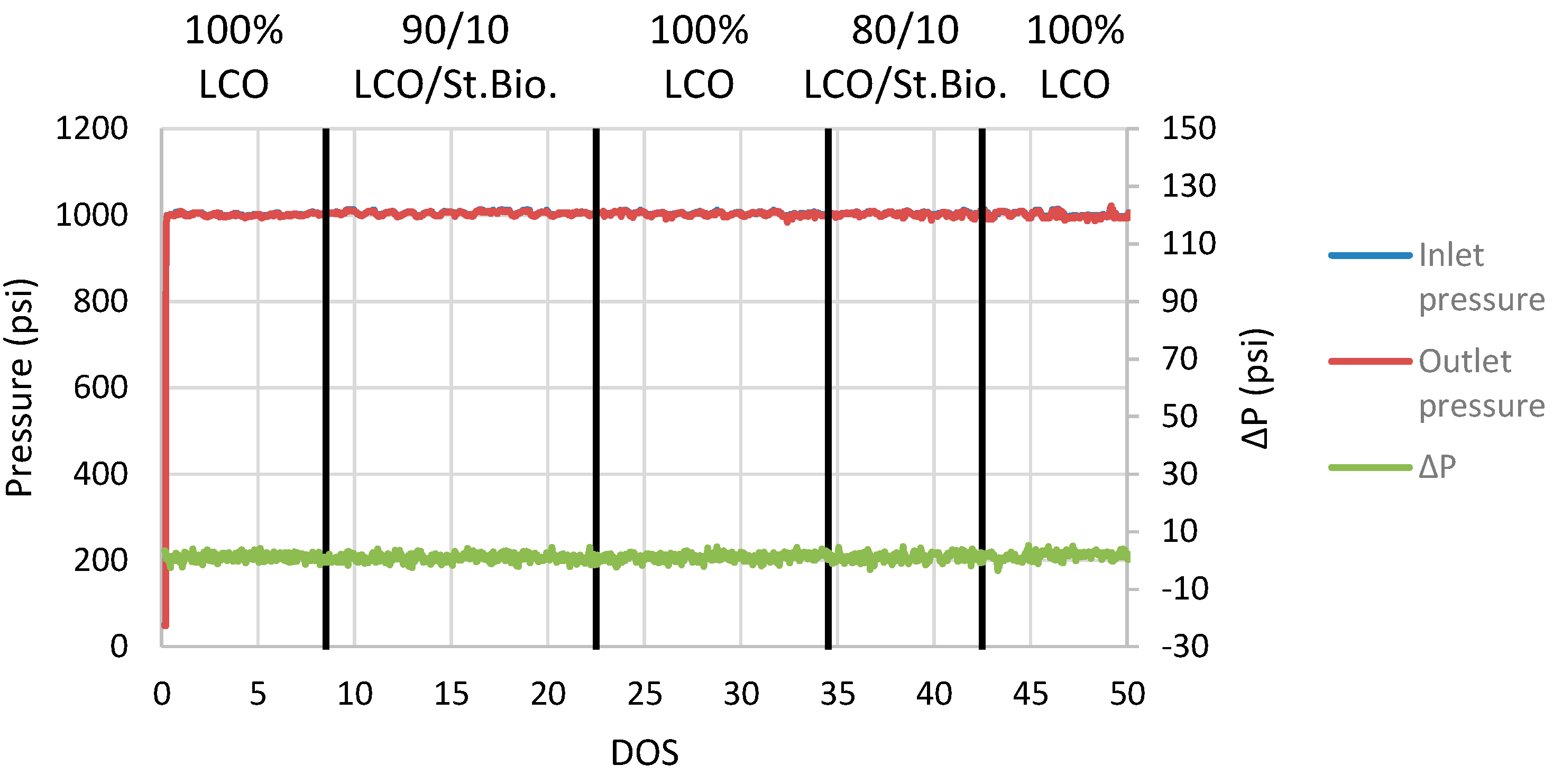

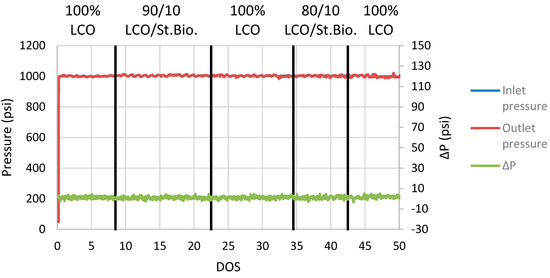

The effect of stabilized biocrude on ΔP is presented in Figure 8, where it is noticed that the stabilized biocrude addition does not induce any ΔP variations indicating catalyst activity losses. No coke formation nor any coke build-up was noticed after 49 DOS of continuous operation, which indicates that the first mild hydrotreatment stabilization step of biocrude was able to improve the raw biocrude properties and, more specifically, to remove the oxygenate compounds and to transform the carboxylic acids and esters to aliphatic hydrocarbons with almost zero oxygen content. Coprocessing testing validated the effective cofeeding of the stabilized biocrude to an LCO hydrotreatment plant, leading to hydrogen consumption benefits for the refinery without catalyst blockage, rendering a high-quality hybrid total liquid. The only drawback observed during the research is the negative effect on HDS catalyst activity that can be counterbalanced with the increase in the operation temperature. In general, it was observed that advanced fuels can be produced via the integration of a partially stabilized biocrude in an LCO hydrotreatment plant, as liquid products consisting of jet and diesel boiling-range hydrocarbons can be produced.

Figure 8.

ΔP plot during coprocessing of LCO and stabilized biocrude blends.

4. Discussion

Today, spent coffee grounds represent the largest waste stream generated in coffee beverage preparation and instant coffee production, with an estimated annual volume of 60 million tons worldwide. This significant quantity highlights the need to enhance and repurpose this waste through efficient circular economy strategies, one of which includes the production of advanced biofuels. Hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) is an advanced thermochemical technology for biofuel production, valued for its flexibility with different feedstocks, as it can process both wet and dry materials. As a result, the HTL can be easily applied also in processing spent coffee grounds, resulting in a product called HTL biocrude. However, as biocrude has high oxygen content that causes instability problems, its upgrading is essential prior to its use as an alternative fuel. Thus, the primary aim of this manuscript was to first examine the mild hydrotreatment stabilization of an HTL biocrude derived from spent coffee grounds and, secondly, to explore the integration of this stabilized biocrude into a light cycle oil refinery stream.

In general, hydrotreatment of HTL biocrude leads to a product consisting of the organic and the aqueous phase. Measurements on the aqueous phase have shown that it is 99% water; thus, the organic phase is the main liquid product that is called stabilized biocrude. During the current step, the effect of the hydrotreatment operating conditions on product quality and process performance was explored by testing two different hydrotreating temperatures (603 K and 633 K) and two hydrogen-to-oil ratios (3000 scfb and 5000 scfb). The results have shown that the oxygen content was reduced almost to zero in all tested conditions, which confirms the effectiveness of the hydrotreatment to fully remove the oxygen from the neat biocrude. In addition, hydrotreatment increased the heating value that was raised from 35 MJ/kg (raw biocrude) to 46 MJ/kg (stabilized biocrude), reduced the viscosity from 27.7 cSt (raw biocrude) to less than 7 cSt (stabilized biocrude) and reduced also the density, improving in that way the quality of the stabilized biocrude in all examined conditions. However, based on the gas product composition analysis, it was found that hydrodeoxygenation reactions are competitive to hydrodesulfurization reactions and it is preferable to perform the hydrotreatment process at higher hydrogen-to-oil ratios. From the tested conditions, it was found that the optimum case is to run the process at 603 K, 6.9 Mpa, 5000 scb hydrogen-to-oil ratio and 1 h−1 LHSV.

The resulting stabilized biocrude was further integrated in an LCO hydrotreatment plant to investigate the effectiveness of the catalyst to process 10 or 20% v/v of stabilized biocrude with LCO. It was found that the integration of the stabilized biocrude into an LCO hydrotreatment plant offers benefits, including reduced hydrogen consumption for the refinery and a resulting product with a higher heating value and lower sulfur content, all while maintaining the properties of the original LCO hydrotreatment product and avoiding ΔP fluctuations in the process. The primary drawback noted in this study is a reduction in HDS catalyst activity; however, this can be mitigated by increasing the operating temperature. Overall, the research demonstrates that incorporating a partially stabilized biocrude into an LCO hydrotreatment plant enables the production of advanced fuels with hydrocarbons in the jet and diesel ranges.

For a commercial application perspective, the advantage of this technological pathway is the use of a decentralized HTL plant, which can be situated near biomass production sites. By transporting only the biocrude to a central refinery, transportation costs are reduced due to the higher volumetric energy density of the oil compared to raw biomass. Furthermore, refineries have many different plants targeting a big variety of products like chemicals, fuels and asphalt. As a result, there are multiple points where the HTL biocrude can be inserted within a refinery leading to different final products. Some possible suggested points are in various processing units after a mild upgrading of biocrude, before the predistillation phase without treatment or as a drop-in fuel after more severe upgrading of the biocrude. The last approach has the lowest risk for the refinery, while integration at the predistillation unit has the highest risk. The most common strategy, which is used also for pyrolysis bio-oil, is the insertion of a stabilized biocrude to a certain processing unit [47]. However, this approach requires further investigation on the stabilization of biocrude. At the moment, the stabilization of biocrude via hydrodeoxygenation remains challenging. There are many issues that have to be addressed prior its commercialization. Some of them are to find suitable catalysts that will increase the yields with high stability and life expectancy. Furthermore, studies on reaction routes during the stabilization of biocrude are necessary to better understanding the effect on catalyst performance and to avoid catalyst damaging and coke formation. In addition, technoeconomic research is important to explore the economic feasibility of the described technology at the industrial level. Studies at higher TRL 6-7 hydrotreatment plants are required to provide operational data closer to industrial units’ operation. Finally, sustainability assessment studies are missing from the literature, especially in the part of coprocessing. Based on the above, the results of the current study establish foundational knowledge in both biocrude stabilization and its integration into an LCO hydrotreatment refinery process, moving the research of the current field one step forward to commercialization.

5. Conclusions

The main objective of the manuscript was to stabilize an HTL biocrude produced via hydrothermal liquefaction of spent coffee grounds and then to integrate the stabilized biocrude in an LCO hydrotreatment process for coprocessing. The results have shown that:

- The HTL biocrude consists mainly of oleic acid (23.28 wt%), n-hexadecanoic acid or palmitic acid (C16:0, 13.19 wt%), 9,12-octadecanoic acid or linoleic acid (C18:2, 11.77 wt%), 7-octadecanoic acid (C18:1, 9.11 wt%) and hexadecenoic acid or palmitoleic acid (C16:1, 8.78 wt%).

- Hydroprocessing successfully stabilized the HTL biocrude by removing the oxygen content from the initial feedstocks and improving its properties (density, viscosity, heating value, oxygen content, water content and H/C ratio).

- Stabilized biocrude after mild hydrotreatment consists mainly of aliphatic hydrocarbons by >90 wt%. More specifically, it consists of 83.6–86.2 wt% alkanes, 1.7–4.8 wt% cycloalkanes and 2.0–2.7 wt% alkene depending on the operation conditions of hydrotreatment.

- The optimum hydrotreating condition was identified at 603 K temperature, 6.9 MPa pressure, 5000 scfb H2/biocrude ratio and 1 h−1 LHSV.

- Cofeeding stabilized biocrude with LCO in the hydrotreating process favors hydrogen consumption but leads to temporary HDS catalyst deactivation that can be overcome via temperature increase.

Author Contributions

A.D.: methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, investigation, validation, data curation, writing—review and editing. S.B.: conceptualization, validation, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund of the European Union and Greek national funds through the Operational Program Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation, under the call RESEARCH—CREATE—INNOVATE (project code: Τ2EDK-00189, “Production of sustainable biofuels and value-added products from municipal organic solid wastes of catering services—Brew2Bio”).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses and/or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript and in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| CERTH | Centre for Research & Technology Hellas |

| CPERI | Chemical Process & Energy Resources Institute |

| DMDS | Dimethyl Disulfide |

| DOS | Days On Stream |

| DP | Drop Pressure |

| GC | Gas Chromatograph |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| HDO | Hydro-Deoxygenation reactions |

| HTL | Hydrothermal Liquefaction |

| HVV | High Heating Value |

| I.D. | Inlet Diameter |

| LHSV | Liquid Hourly Space Velocity |

| MCR | Micro Carbon Residue |

| NiMo | Nickel—Molybdenum catalyst |

| SAF | Sustainable Aviation Fuels |

| SimDis | Simulated Distillation |

| TAN | Total Acid Number |

| TCC | Thermochemical Conversion technologies |

| TRL 3 | Technology Readiness Level 3 |

| XRFS | X-ray fluorescence spectrometer |

References

- Franca, A.S.; Oliveira, L.S. Coffee processing solid wastes: Current uses and future perspectives. In Agricultural Wastes; Book Chapter 8; Ashworth, G.S., Azevedo, P., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-60741-305-9. [Google Scholar]

- Forcina, A.; Petrillo, A.; Travaglioni, M.; Chiara, S.; Felice, F. A comparative life cycle assessment of different spent coffee ground reuse strategies and a sensitivity analysis for verifying the environmental convenience based on the location of sites. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seehar, T.H.; Toor, S.S.; Shah, A.A.; Pedersen, T.H.; Rosendahl, L.A. Biocrude Production from Wheat Straw at Sub and Supercritical Hydrothermal Liquefaction. Energies 2020, 13, 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, A.; Yaashikaa, P.R.; Kumar, P.S.; Thmarai, P.; Deivayanai, V.C.; Rangasamy, G. A comprehensive review on techno-economic analysis of biomass valorization and conversion technologies of lignocellulosic residues. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 200, 116822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, A.; Bezergianni, S. Hydrothermal liquefaction of various biomass and waste feedstocks for biocrude production: A state of the art review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castello, D.; Haider, M.S.; Rosendahl, L.A. Catalytic upgrading of hydrothermal liquefaction biocrudes: Different challenges for different feedstocks. Renew. Energy 2019, 141, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasakis, K.; Biller, P.; Madsen, R.; Glasius, M.; Johannsen, I. Continuous hydrothermal liquefaction of biomass in a novel pilot plant with heat recovery and hydraulic oscillation. Energies 2018, 11, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, A.; Bezergianni, S. Hydrothermal Liquefaction Biocrude Stabilization via Hydrotreatment. Energies 2024, 17, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Yu, T.; Zhang, S. Enhanced aromatic hydrocarbon production from bio-oil hydrotreating-cracking by Mo-Ga modified HZSM-5. Fuel 2020, 269, 117386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, M.S.; Castello, D.; Rosendahl, L.A. Two-stage catalytic hydrotreatment of highly nitrogenous biocrude from continuous hydrothermal liquefaction: A rational design of the stabilization stage. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 139, 105658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohansal, K.; Sanchez, E.L.; Khare, S.; Bjorgen, K.O.P.; Haider, M.S.; Castello, D.; Lovas, T.; Rosendahl, L.A.; Pedersen, T.H. Automotive sustainable diesel blendstock production through biocrude obtained from hydrothermal liquefaction of municipal waste. Fuel 2023, 350, 128770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindfors, C.; Ellito, D.C.; Prins, W.; Oasmaa, A.; Lehtonen, J. Co-processing of Biocrudes in Oil Refineries. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, A.; Liakos, D.; Pfisterer, U.; Moustaka-Gouni, M.; Karonis, D.; Bezergianni, S. Impact of hydrogenation on miscibility of fast pyrolysis bio-oil with refinery fractions towards bio-oil refinery integration. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 151, 106171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Jahromi, H.; Rahman, T.; Baltrusitis, J.; Hassa, E.B.; Torbert, A.; Adhikari, S. Hydrotreatment of pyrolysis bio-oil with non-edible carinata oil and poultry fat for producing transportation fuels. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 245, 107753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horacek, J.; Kubicka, D. Bio-oil hydrotreating over conventional CoMo & NiMo catalysts: The role of reaction conditions and additives. Fuel 2017, 198, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biller, P.; Sharma, B.K.; Kunwar, B.; Ross, A.B. Hydroprocessing of bio-crude from continuous hydrothermal liquefaction of microalgae. Fuel 2015, 159, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Z.; Li, J.; He, C.; Xu, T. Catalytic hydrotreatment upgrading of biocrude oil derived from hydrothermal liquefaction of animal carcass. Fuel 2022, 317, 123528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, S.; Santosa, D.M.; Brady, C.; Swita, M.; Ramasamy, K.K.; Thorson, M.R. Extended catalyst lifetime testing for HTL biocrude hydrotreating to produce fuel blendstocks from wet wastes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 12825–12832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM-4052; Standard Test Method for Density, Relative Density, and API Gravity of Liquids by Digital Density Meter. Designation: D4052-22; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM D-7169-23; Standard Test Method for Boiling Point Distribution of Samples with Residues such as Crude Oils and Atmospheric and Vacuum Residues by High Temperature Gas Chromatography. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- ASTM D-5291; Standard Test Methods for Instrumental Determination of Carbon, Hydrogen, and Nitrogen in Petroleum Products and Lubricants. Designation: D5291-21; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D-4294-21; Standard Test Method for Sulfur in Petroleum and Petroleum Products by Energy Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D4629; Standard Test Method for Trace Nitrogen in Liquid Hydrocarbons by Syringe/Inlet Oxidative Combustion and Chemiluminescence Detection. Designation: D4629-17; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D-6304-20; Standard Test Method for Determination of Water in Petroleum Products, Lubricating Oils, and Additives by Coulometric Karl Fischer Titration. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM E-203-16; Standard Test Method for Water Using Volumetric Karl Fischer Titration. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- ASTM D-664; Standard Test Method for Acid Number of Petroleum Products by Potentiometric Titration. Designation: D664-18; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM D-445-21; Standard Test Method for Kinematic Visvosity of Transparent and Opaque Liquids (and Calculation of Dynamic Viscosity). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D-976-06; Standard Test Method for Calculated Cetane Index of Distillate Fuels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2006.

- ASTM D-97; Standard Test Method for Pour Point of Petroleum Products. Designation: D97-02; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2002.

- ASTM D4530; Standard Test Method for Determination of Carbon Residue (Micro Method). Designation: D4530-15 (Reapproved 2020); ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Channiwala, S.A.; Parikh, P.P. A unified correlation for estimating HHV of solid, liquid and gaseous fuels. Fuel 2002, 81, 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, A.; Meletidis, G.; Pfisterer, U.; Auersvald, M.; Kubicka, D.; Bezergianni, S. Integration of stabilized bio-oil in light cycle oil hydrotreatment unit targeting hybrid fuels. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 230, 107220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, P.M.; Grunwaldt, J.D.; Jensen, P.A.; Knudsen, K.G.; Jensen, A.D. A review of catalytic upgrading of bio-oil to engine fuels. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2011, 407, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadarwati, S.; Hu, X.; Gunawan, R.; Westerhof, R.; Gholizadeh, M.; Hasan, M.D.M.; Li, C.Z. Coke formation during the hydrotreatment of bio-oil using NiMo and CoMo catalysts. Fuel Process. Technol. 2017, 155, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, M.; Gunawan, R.; Hu, X.; Kadarwati, S.; Westerhof, R.; Chaiwat, W.; Hasan, M.; Li, C.-Z. Importance of hydrogen and bio-oil inlet temperature during the hydrotreatment of bio-oil. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 150, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Gholizadeh, M.; Tran, C.C.; Kaliaguine, S.; Li, C.Z.; Olarte, M.; Garcia-Pere, M. Hydrotreatment of Pyrolysis Bio-Oil: A Review. Fuel Process. Technol. 2019, 195, 106140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, M.; Gunawan, R.; Hu, X.; Hasan, M.M.; Kersten, S.; Westerhof, R.; Chaitwat, W.; Li, C.Z. Different reaction behaviours of the light and heavy components of bio-oil during the hydrotreatment in a continuous pack-bed reactor. Fuel Process Technol. 2016, 146, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, A.; Olarte, M.; Santosa, D.; Elliot, D.C.; Jones, B. A review and perspective of recent bio-oil hydrotreating research. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 491–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Ma, L.; Dong, R. An overview on catalytic hydrodeoxygenation of pyrolysis oil and its model compounds. Catalysts 2017, 7, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero-Lanzac, T.; Palos, R.; Hita, I.; Arandes, L.M.; Rodriguez-Mirasol, J.; Cordero, T.; Bilbao, J.; Castano, P. Revealing the pathways of catalyst deactivation by coke during the hydrodeoxygenation of raw bio-oil. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 239, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella, L.; Stankovikj, F.; Sanchez, J.L.; Gonzalo, A.; Arauzo, J.; Garcia-Perez, M. Bio-oil hydrotreatment for enhancing solubility in biodiesel and the oxidation stability of resulting blends. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero-Lanzac, T.; Palos, R.; Arandes, J.M.; Castano, P.; Rodriguez-Mirasol, J.; Cordero, T.; Bilbao, J. Stability of an acid activated carbon based bifunctional catalyst for the raw bio-oil hydrodeoxygenation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 203, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manara, P.; Bezergianni, S.; Pfisterer, U. Study on phase behavior and properties of binary blends of bio-oil/fossil-based refinery intermediates: A step toward bio-oil refinery integration. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 165, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, S.; Apfelbacher, A.; Schulzke, T. Fractionated condensation of pyrolysis vapours from ablative flash pyrolysis. In Proceedings of the 22rd European Biomass Conference & Exhibition, Hamburg, Germany, 23–26 June 2014; pp. 1127–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, B.C.; Checa, R.; Lorentz, C.; Afanasiev, P.; Laurenti, D.; Geantet, C. Catalytic hydroconversion of HTL micro-algal bio-oil into biofuel over NiWS/Al2O3. Algal Res. 2023, 71, 103012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, J.M.; Albrecht, K.O.; Billing, J.M.; Schmidt, A.J.; Hallen, R.T.; Schaub, T.M. Assessment of hydrotreatment for hydrothermal liquefaction biocrudes from sewage sludge, microalgae, and pine feedstocks. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 8483–8493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollakota, A.; Shu, C.M.; Sarangi, P.K.; Shadangi, K.P.; Rakshit, S.; Kennedy, J.F.; Gupta, V.K.; Sharma, M. Catalytic hydrodeoxygenation of bio-oil and model compounds-Choice of catalysts, and mechanisms. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 187, 113700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).