Abstract

The ongoing energy transformation and growing share of renewable energy sources (RES) in electricity production force the search for large-scale energy storage facilities as a possibility for storing electricity from RES because its production is not correlated with the current demand in the power grid. This article discusses the use of salt caverns as large-scale energy storage facilities, proposing a combination of the possibilities of storing energy in natural gas and energy stored in compressed air. Based on the selected potential area where such a storage facility could operate in Poland, the optimal operating parameters of storage caverns were estimated. Several possible cavern exploitation scenarios were analyzed to estimate the impact of the convergence phenomenon in salt caverns on the active storage volume over the long term of exploitation. The obtained results showed that even a high frequency of cavern exploitation cycles does not significantly affect the loss of its capacity due to the convergence phenomenon. The results confirmed the possibility of the effective use of this type of installation for storing surpluses from RES.

1. Introduction

Cavern underground storage in salt deposits has been known in the world for many years. This type of storage is considered one of the best for storing both natural gas and liquid fuels in terms of their flexibility of operation and ensuring tightness [1]. In the era of ongoing energy transformation and the growing share of renewable energy sources (RES) in the country’s energy balance, it is necessary to look for opportunities to store electricity from RES because its production is not correlated with the current demand in the power grid [2]. Therefore, it is necessary to find a way to store surplus electricity on a large scale and at the same time enable its rapid release in the event of a sudden increase in the demand for electricity in the network. One way to store electricity is to convert it into energy in another form, which allows for its permanent storage in an easy and relatively economical way, both for short and long periods of time [3]. In the case of using large-scale energy storage in salt caverns, energy stored in the form of natural gas, hydrogen, and compressed air energy can be taken into account [4,5].

Due to the increasing share of renewable energy sources in the Polish energy balance, one of the biggest disadvantages of which is the stochastic process of operation, it is becoming necessary to look for possibilities of storing surplus energy generated in the period when there is no high demand for electricity in the power grid [4,5]. In the era of the ongoing energy transformation and striving to achieve the goal of “zero emissions”, the use of renewable energy sources in the total energy balance will increase, and consequently, the demand for increasing energy storage capacities will increase. However, achieving the above goal will not happen as quickly as it might seem, and hence, a transition period is necessary during which the energy sector will gradually reduce the emission of harmful substances into the atmosphere. One of the fuels, the increased use of which in the energy sector will significantly reduce the level of emissions compared to coal combustion, is natural gas. Hence, from the perspective of the coming decades, the most advantageous method of storing energy on a large scale will be technologies using a combination of combustion of gaseous fuels in combination with renewable energy sources in order to re-generate electricity.

Surplus electricity from renewable energy sources on a local scale (several individual recipients) is best stored using various types of batteries or accumulators. In the case of large-scale installations, where we are talking about a scale of several dozen or several hundred TWh of energy to store, “conventional” batteries turn out to be ineffective. Building a storage facility based on such batteries would require connecting several thousand such batteries. In the case of many such installations, there will be problems with the possibility of obtaining rare metals needed for their construction. The installation requires huge areas for construction. Using pumped-storage power plants to store energy is a good way to store energy surpluses from the grid, but it is not always possible in a given location. They require access to appropriate hydrological conditions and also huge areas [6].

Therefore, if we are looking for opportunities to store energy on a large scale, we should focus on the use of geological structures that allow for locating storage facilities below the ground surface with little use of space on the surface [7].

When comparing underground gas storage in salt caverns to underground gas storage in depleted porous reservoirs or deep aquifers, they have several advantages, such as greater tightness and medium release rate. It is possible to achieve many rapid discharge cycles compared to depleted reservoirs, where typically there is one discharge cycle per year [8]. If we are looking for a high frequency of storage cycles, we can also consider above-ground tanks, but here again, there is a problem with the capacity of such tanks and the need to develop a large area.

Compressed air energy storage in salt caverns (CAES) is one way of storing excess electrical energy produced by converting it into mechanical energy, and then generating it “anew” and feeding it back to the grid when needed. The solution proposed in CAES technology provides significant savings in terms of energy demand because all the electrical energy produced is fed directly into the grid. In a classic gas turbine installation, a large part of it (energy) is consumed by driving compressors supplying the turbine with air [4,5]. The possibility of storage means that the electrical energy produced does not have to be fed into the grid at the time of production [3,9]. The advantage of this type of installation is the possibility of rapid filling and emptying, which means that such storage facilities can be successfully used to compensate for excess electrical energy in the grid and relatively quickly supplement its shortages [10,11]. CAES salt caverns were used in 1978 in Huntorf, Germany, where the installation served as an emergency power supply for a nuclear power plant (the current capacity of the installation is 320 MW) [12]. An installation of this type was also built in McIntosh, USA in 1991 (110 MW), and in 2012, a small CAES installation was launched in Gaines, Texas, USA, operating in conditions close to isothermal [2,4]. Many years of failure-free operation of the above installations confirmed the technical possibilities of using salt caverns as peak energy storage facilities that can be quickly (several dozen minutes/several hours) emptied or filled [2,5].

The analyses conducted in the following part focus on the general parameters of the installation’s operation, but after entering more detailed data, they can be adjusted to specific geological conditions.

Although they are concerned with the use of the potential of salt deposits in Poland and are based on the principles of salt cavern design adopted in Poland, they can also be successfully implemented in other locations in the world with a similar geological structure.

2. CAES Potential in Salt Caverns in Poland

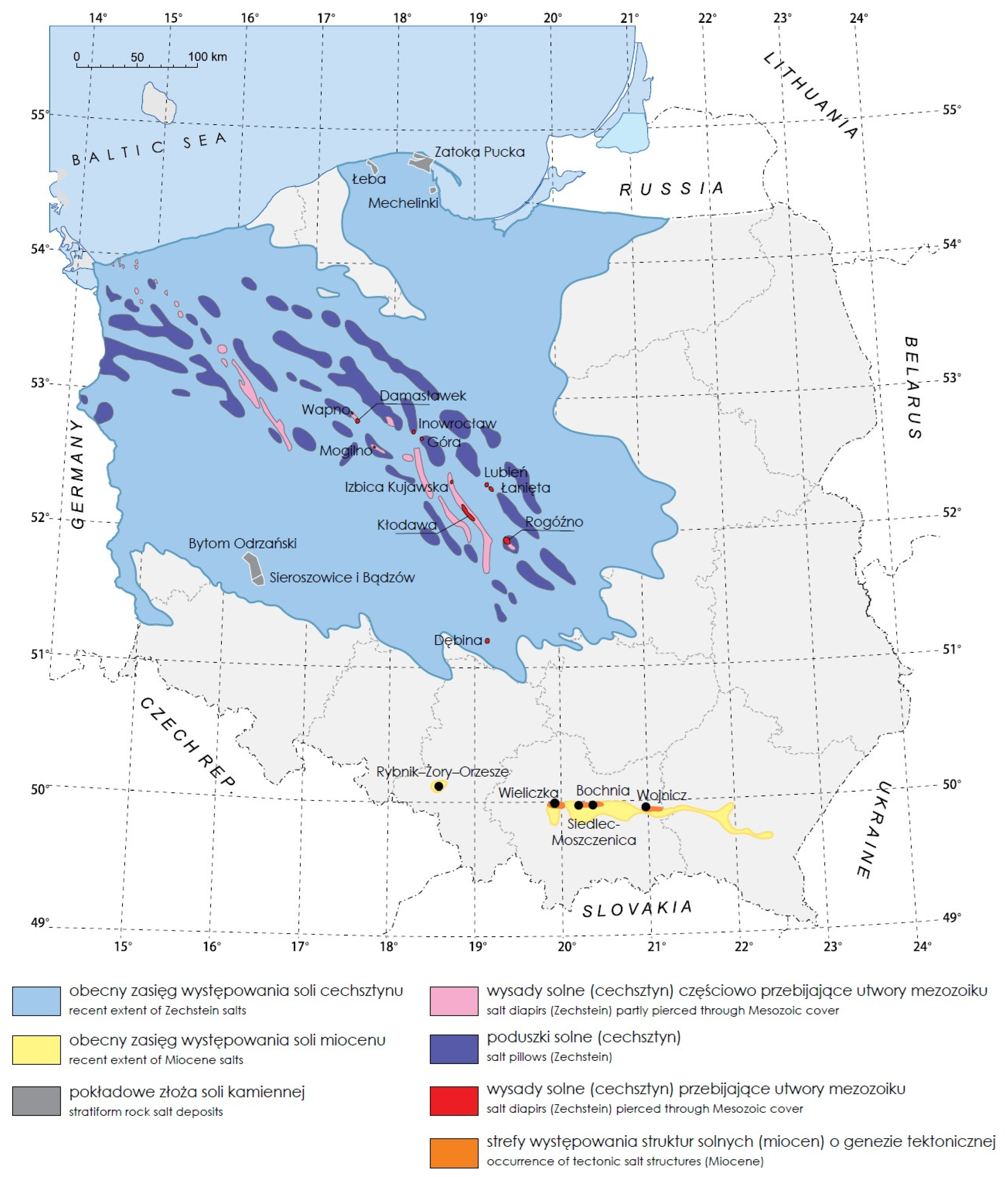

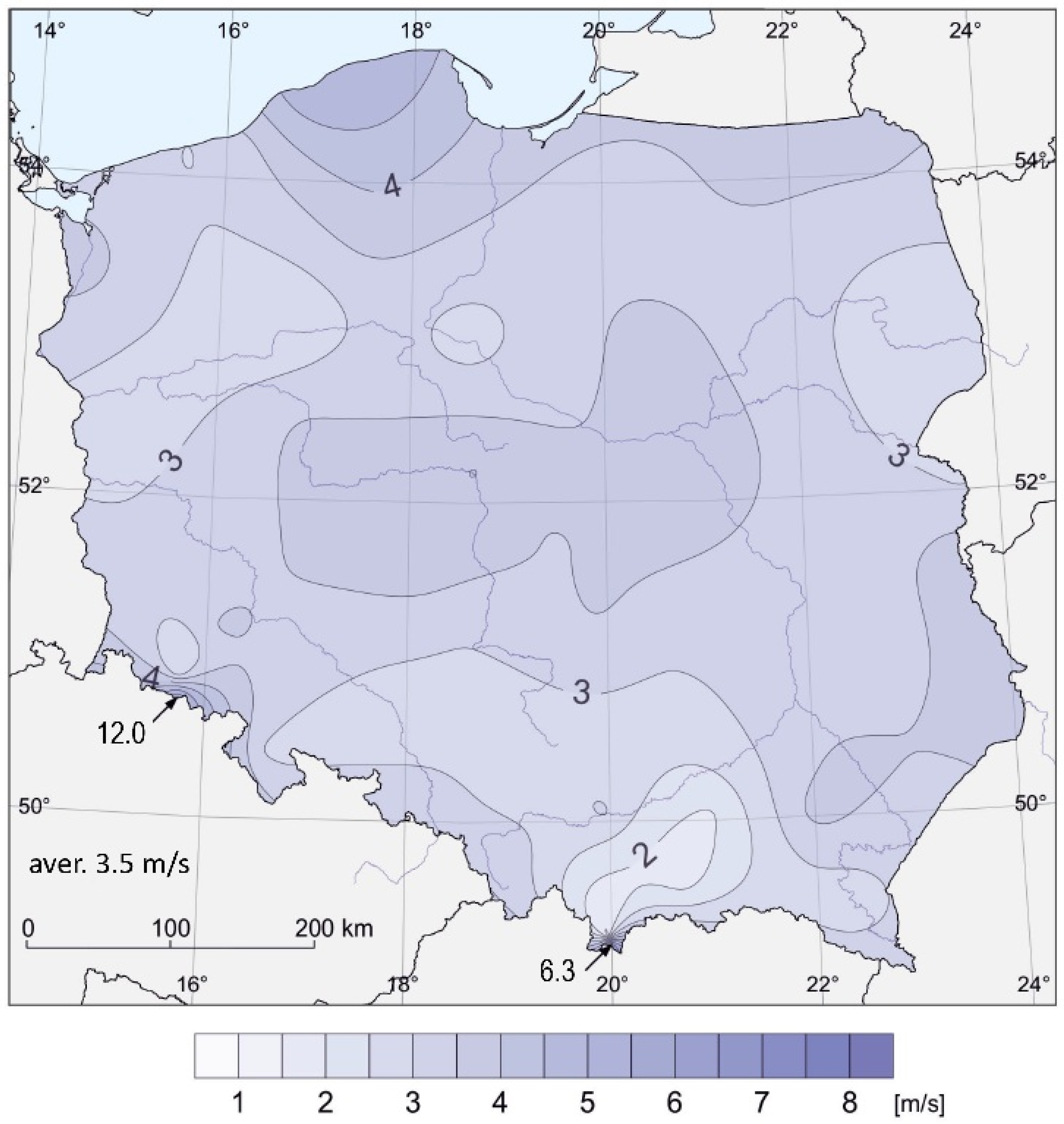

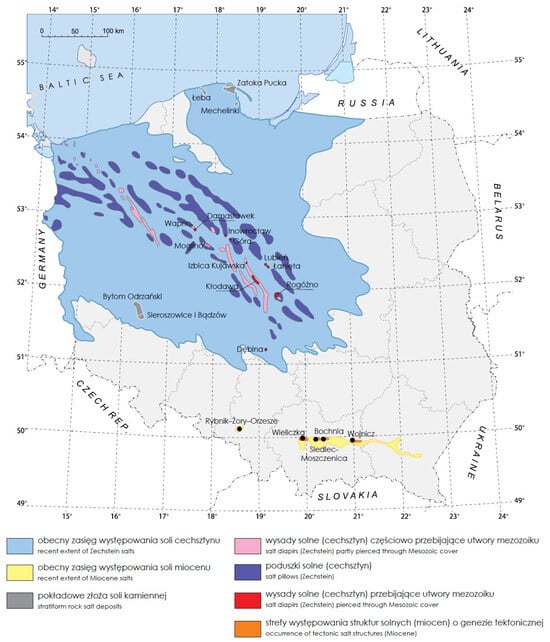

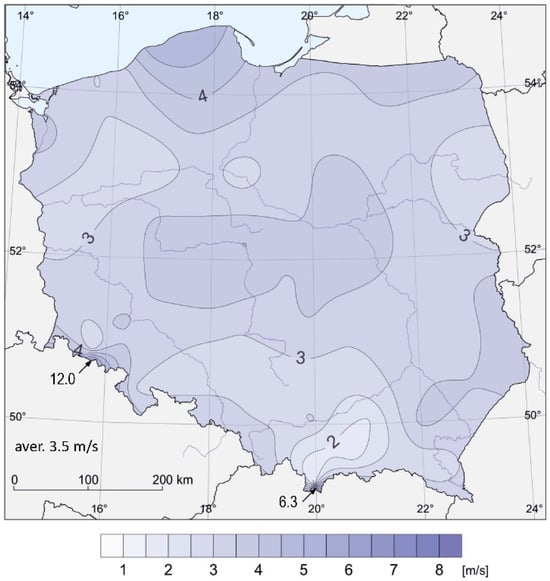

Based on the assessment of the potential of identified salt deposits in Poland and the determination of the possibility of using these structures as potential compressed air energy storage facilities [1,2,13], an analysis was carried out in comparison with the map of average wind speeds blowing in Poland. Based on the analysis of salt deposits (Figure 1) and wind speed (Figure 2), the most favorable conditions for the construction of a CAES power plant occur in the area of the Łeba elevation and the Bay of Puck. Based on borehole data, the average thickness of salt deposits ranges from 150 to 160 m at a depth of 600 to 900 m below ground level [13]. It can be assumed that these conditions are similar to the existing CAES installation in Huntorf, where the caverns are located at an interval of 650–900 m below ground level [2]. The entire area of occurrence of central Polish salt domes can also be considered a potential location for such a storage facility [13,14].

Figure 1.

Map of rock salt deposits in Poland (based on ref. [14]).

Figure 2.

Mean wind speed at 10 m above sea level in open terrain in Poland (based on ref. [15]).

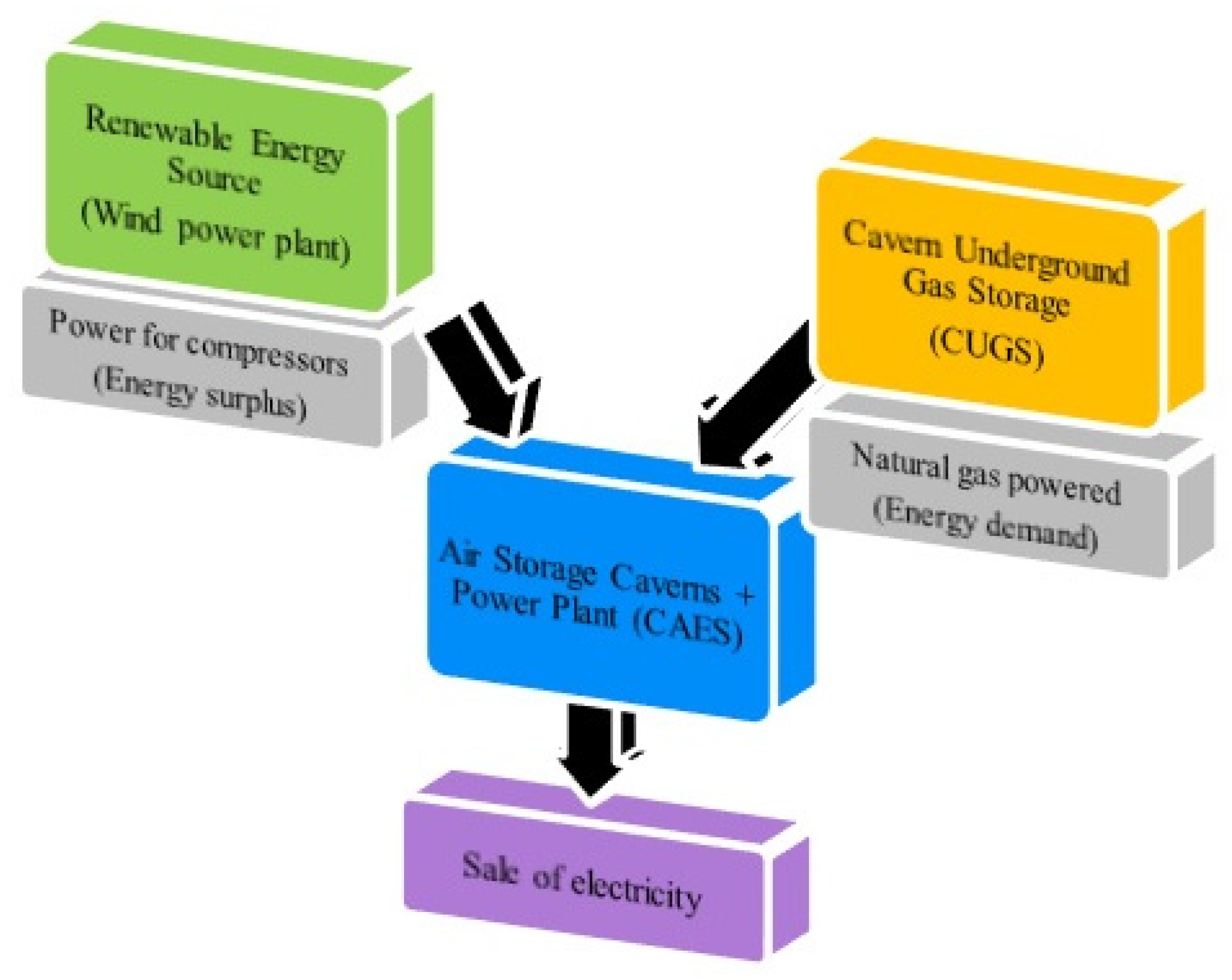

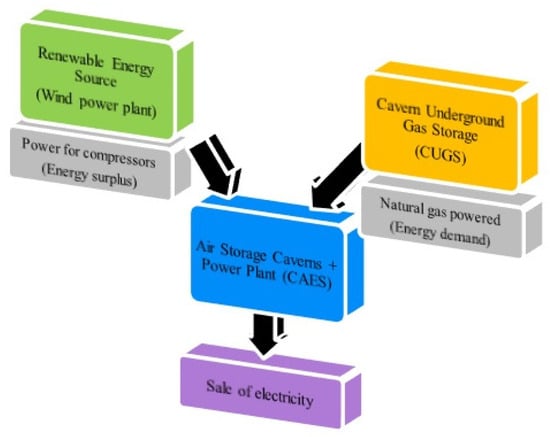

CAES storage systems largely make electricity production independent of constant access to a renewable source (e.g., wind). If the wind force does not reach the established minimum required to drive a wind turbine 24 h a day, during periods of “wind calm”, it is possible to use the energy stored in compressed air to produce electricity in a gas turbine. Thanks to this, CAES technology can be treated as a supplement to wind energy during periods when energy production from wind turbines is not possible [5]. However, the basic goal of using the CAES system is to cover peak demand, which is why it is necessary to consider locations where the average wind speed is as high as possible, which is why such an area was selected as the most advantageous for the construction of wind turbines, which are the source of drive for compressors [12]. According to the author, in order to use the advantages of the CAES installation most effectively, it would be most advantageous to connect it to a natural gas storage facility (Figure 3) so that the storage potential of this medium can also be used. Hence, potential places where it would be possible to build a compressed air storage facility in Poland are primarily locations located near the existing natural gas cavern storage facilities, i.e., CUGS Mogilno and CUGS Kosakowo [1,13].

Figure 3.

The concept of cooperation between a wind farm, a CAES power plant, and a natural gas storage facility in a cavern (CUGS)—own study.

2.1. Cavern Underground Gas Storage in Poland (CUGS)

Currently, there are two cavern storage facilities for natural gas in Poland. Their main task is to balance the peak demand for gas in the network. According to data from the Gas Storage Poland Company website [16], the active storage capacity of the CUGS Mogilno is 580.92 million m3 (in 14 storage caverns); maximum injection capacity: 9.60 million m3/day, withdrawal capacity: 18.00 million m3/day. Currently, the CUGS Kosakowo has 296.80 million m3 of active storage capacity (in eight caverns); maximum injection capacity: 2.40 million m3/day, maximum withdrawal capacity: 9.60 million m3/day.

2.2. Compressed Air Energy Storage Cavern (CAES)

When analyzing the work of the CAES cavern, it should be noted that it operates in a relatively small pressure range (compared to natural gas storage caverns)—in the Huntorf installation, the range is 5–7 MPa; However, the cavern empties within 2 h (the gas cavern empties within around a dozen days). The rapid pressure changes during operations will cause changes in the temperature of the stored medium, mass rock, and casing [17].

Based on the parameters of the existing CAES installation in Huntorf, assumptions for calculations were determined. They do not result from geological conditions but from technical and economic conditions related to the strength of the operating pipes, casing pipes, and cement, which are exposed to high-temperature fluctuations and rapid stress changes in the operating conditions of the CAES system. For example, in the Huntorf power plant, the operating efficiency exceeds 1 million m3/h from one borehole, which requires the use of operating pipes with diameters of 24” [12,18], which is significant compared to the diameters commonly used in the drilling industry, and at the same time, requires the use of better materials (especially in terms of strength). The parameters of the storage caverns for storing energy and gas were adopted based on the average values from geological data for the Łeba and Mechelinki deposits and in relation to the existing KPMG Kosakowo storage facility. The parameters adopted for further calculations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Salt deposit parameters and maximum leachable cavern volume.

Based on the above assumptions, the maximum geometric volume of the cavern that could be constructed in a deposit of this thickness was estimated. The active volume was determined based on the volume loss during leaching of the cavern into insoluble parts at the level of 20% of the geometric volume [19].

Of course, the values presented in the table above are the maximum values that can be achieved for the assumed parameter values.

Assuming the parameters of the Huntorf power plant [4,20] (with a capacity of approx. 300 MW and a cavern volume of 310,000 m3, emptied in 2 h) as a reference point, the active volume of caverns V to generate power P should be [19]:

where

- V—volume in 103 [m3];

- t—working time [h];

- P—power [MW].

The number of caverns n that must be leached to reach the required volume Vactive:

Based on the above relationships, it is possible to estimate the number of caverns that must be made to obtain the required power in a deposit of a given thickness [19]. Assuming a thickness of about 160 m, to achieve a power of approx. 200 MW and energy release for 4 h, two caverns must be made. If the time of energy release is increased, the number of necessary storage caverns must be increased.

2.3. Caverns Parameters

The range of operating pressures of the storage cavern depends primarily on the depth of the cavern foundation, geological structure, stored medium, and the scenario of the storage operation.

The maximum pressure that can be achieved in the cavern is traditionally determined for the depth of the last cemented exploitation pipe and is proportional to the depth, taking into account the micro-fracturing factor (gfrac) determined on the basis of well tests. In practice, for Polish conditions, it is assumed that 0.018 MPa/m +/− 0.001 [19].

It is difficult to provide a general formula for determining the minimum pressure because it depends not only on the depth but also on the strength and creep rate of salt rock, as well as the size and shape of the cavern [19].

Since the operation of the CAES storage cavern does not require very high pressures, hence that the cavern does not have to be very deeply founded, it was decided to adopt parameters similar to the Łeba deposit due to its location for calculations [14]. Therefore, an average level of salt layer deposition can be assumed to be in the interval of 670–890 m, with an average thickness of 160 m.

The cavern parameters were estimated based on the following equations [19]:

where

- hup—thickness of the upper dome of the cavern (assumed 1/3 Dmax);

- hdown—thickness of the lower dome of the cavern (assumed 1/6 Dmax).

The temperature of the rock mass is usually determined according to the geothermal gradient [19]:

where

- Tg0—thermal coefficient, for the Łeba elevation: 283 K;

- gT—geothermal gradient, for the Łeba elevation: 0.01 .

Table 2.

CAES cavern parameters.

Table 3.

CUGS cavern parameters.

For further calculations, the compressed air storage cavern was assumed: pmax = 7 MPa; pmin = 5 MPa.

In the case of caverns used for storing natural gas, the proposed storage facility could use the gas stored in the caverns of the Kosakowo CUGS or it would also be necessary to create caverns for natural gas in the Łeba deposit [19]. By analogy to Kosakowo, the geometric volume of such a single cavern could be about 200,000 m3. Assuming the deposit parameters as seen in Table 1, it is possible to estimate the parameters of the natural gas storage cavern (Table 3).

For further calculations, the natural gas storage cavern was assumed: pmax = 12 MPa; pmin = 4.5 MPa.

where

- Vactive—geometric active volume (storage volume);

- ∆p—working pressure: pmax − pmin;

- R—gas constant: ;

- ρgas—gas density: ;

- Trock—rock mass temperature calculated according to Equation (7): 290.854 K.

Based on Equation (8) [19], the storage capacity of the natural gas cavern was determined to be approximately 14 million mn3 of natural gas.

3. Caverns Working Scenarios

3.1. CAES Cavern Working Scenarios

Assuming the compressed air storage cavern operating parameters adopted in Section 2.2 (4 h of emptying), four variants of the CAES storage operation were adopted for the analyses: daily (365 cycles per year)—scenario I, 2 days (182,5 cycles per year)—scenario II, weekly (52 cycles per year)—scenario III, 2 weeks (26 cycles per year)—scenario IV. Geomechanical and thermomechanical analyses of the storage cavern in the CAES installation confirmed the possibility of performing daily work cycles while maintaining the stability of the salt cavern [17,21,22].

The pressure in the cavern is not constant during the operation, so the rate of convergence changes over time. Generally, the storage operation scenario can be divided into four stages:

- The cavern remains at the pressure pmin for the time ∆tmin;

- The cavern is filled to the pressure pmax during ∆tfill;

- The cavern remains filled to the pressure pmax for the time ∆tmax;

- The cavern is down-loaded to the pressure pmin for the time ∆tempt.

The following operating scenarios were adopted for the CAES cavern convergence analyses (Table 4):

Table 4.

CAES cavern operation scenarios assumed in the calculations.

3.2. CUGS Cavern Working Scenarios

Since the operating cycle of the natural gas storage cavern is slightly different from the compressed air cavern, it was assumed for the analyses that four identical natural gas storage caverns would operate in the storage in an alternating cycle (therefore, convergence calculations were performed for one cavern). It was assumed that the cavern emptying from maximum pressure to minimum pressure would be 30 days, and depending on the scenario, the filling time would be 60 (scenario I) or 120 days (scenario II).

While the CAES installation is shut down, natural gas from the caverns will be released into the transmission network.

The following operating scenarios were adopted for the natural gas cavern convergence analyses (Table 5):

Table 5.

CUGS cavern operation scenarios assumed in the calculations.

4. Convergence of Storage Caverns and Volume Loss

4.1. Methodology

By convergence of the storage cavern, we mean the loss of its volume over time due to the action of the salt creep phenomenon [19].

The loss of the cavern’s active capacity due to convergence is one of the most important issues that arise during the exploitation of storage caverns in rock salt deposits. It is an inevitable phenomenon, and its intensity depends on the depth of the foundation, rheological properties, as well as the operating pressure, in particular, the minimum pressure [17].

The rock mass pressure at the depth of the center of the storage cavern can be estimated based on Equation (9):

where

- ρ—average density of overburden rocks: 2100;

- g—acceleration of gravity: 9.81;

- hmid—depth of the cavern center calculated based on Equation (6).

The convergence speed at maximum pressure can be calculated by Equation (10):

which analogously converges speed at a minimum pressure:

where, based on laboratory tests for Polish conditions, it was determined that [19,23]:

- Ak = 0.000114 ;

- Bk = 0.147;

- nk = 4.089;

- Qk = 2867.9 K;

- η—cavern slenderness: (1.571 for CAES cavern, 1.538 for natural gas cavern).

The convergence speed at maximum and minimum pressure in the CAES and Natural Gas caverns are given in Table 6.

Table 6.

Convergence speed values at maximum and minimum pressures.

The average annual convergence speed is expressed by the Equation (12):

The calculated average annual convergence speed values for each of the adopted cavern operation scenarios are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

The value of the average annual convergence speed for the CAES and natural gas cavern.

Based on the above results, it is clear that in the case of the CAES cavern, the adopted scenario of its operation does not significantly affect the value of the average annual convergence because, in annual terms, the rate of decrease in the cavern volume is comparable. In the case of natural gas storage caverns, however, a noticeable difference in the obtained values is already visible depending on the adopted scenario of operation, but it is worth noting that this rate is lower than in the case of CAES caverns.

4.2. Calculation Results

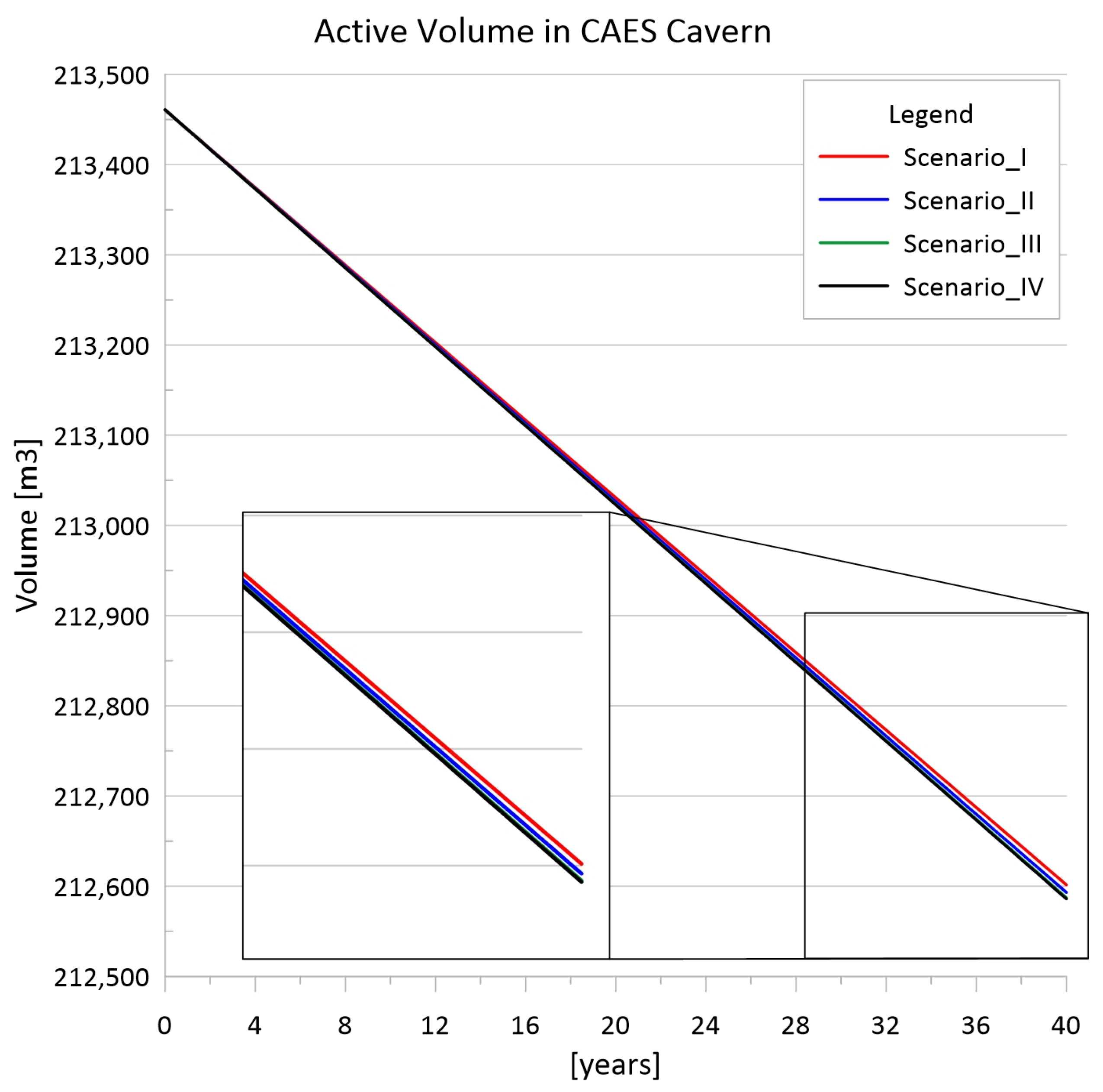

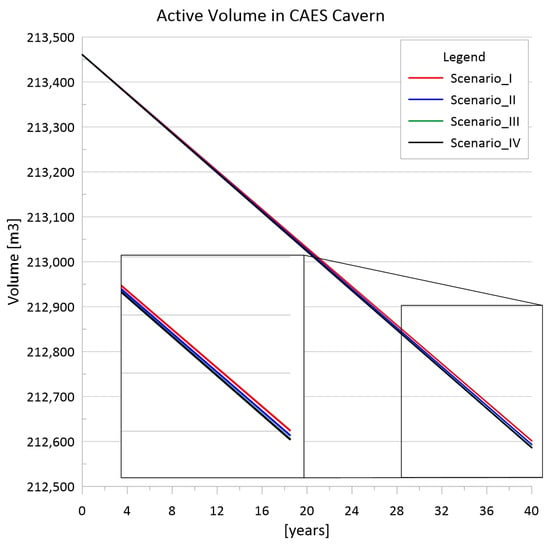

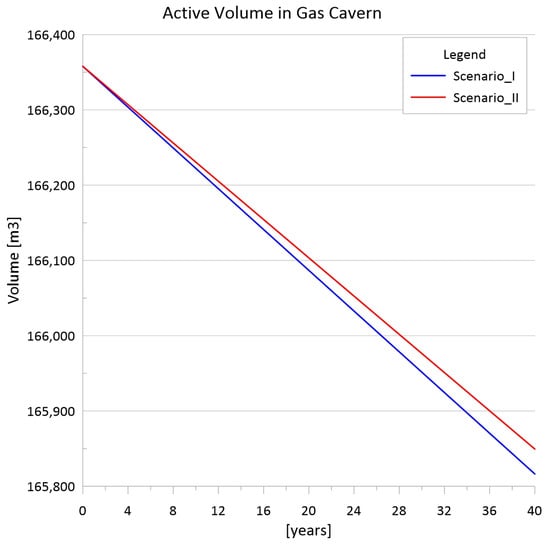

Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 show the results of the calculations performed for the period of 40 years of storage facility operation. The decrease in the active volume of the CAES and natural gas cavern at the first stage is similar, and only after about a dozen years of exploitation do the differences become visible, depending on the adopted scenario.

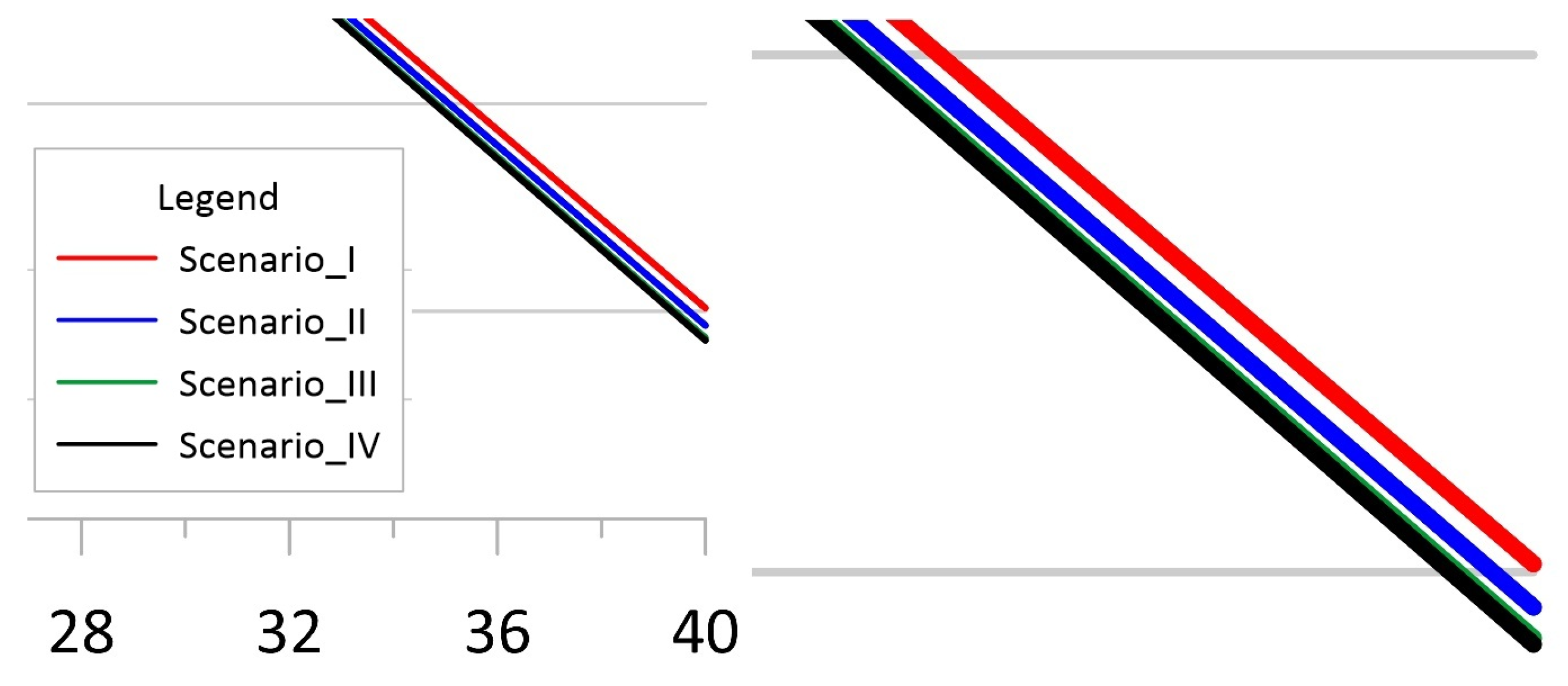

Figure 4.

Decrease in the active volume of the CAES cavern over 40 years of operation.

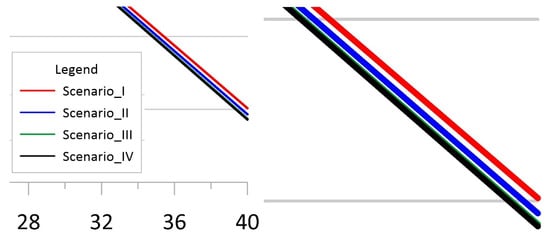

Figure 5.

Additional zoomed sections from Figure 4.

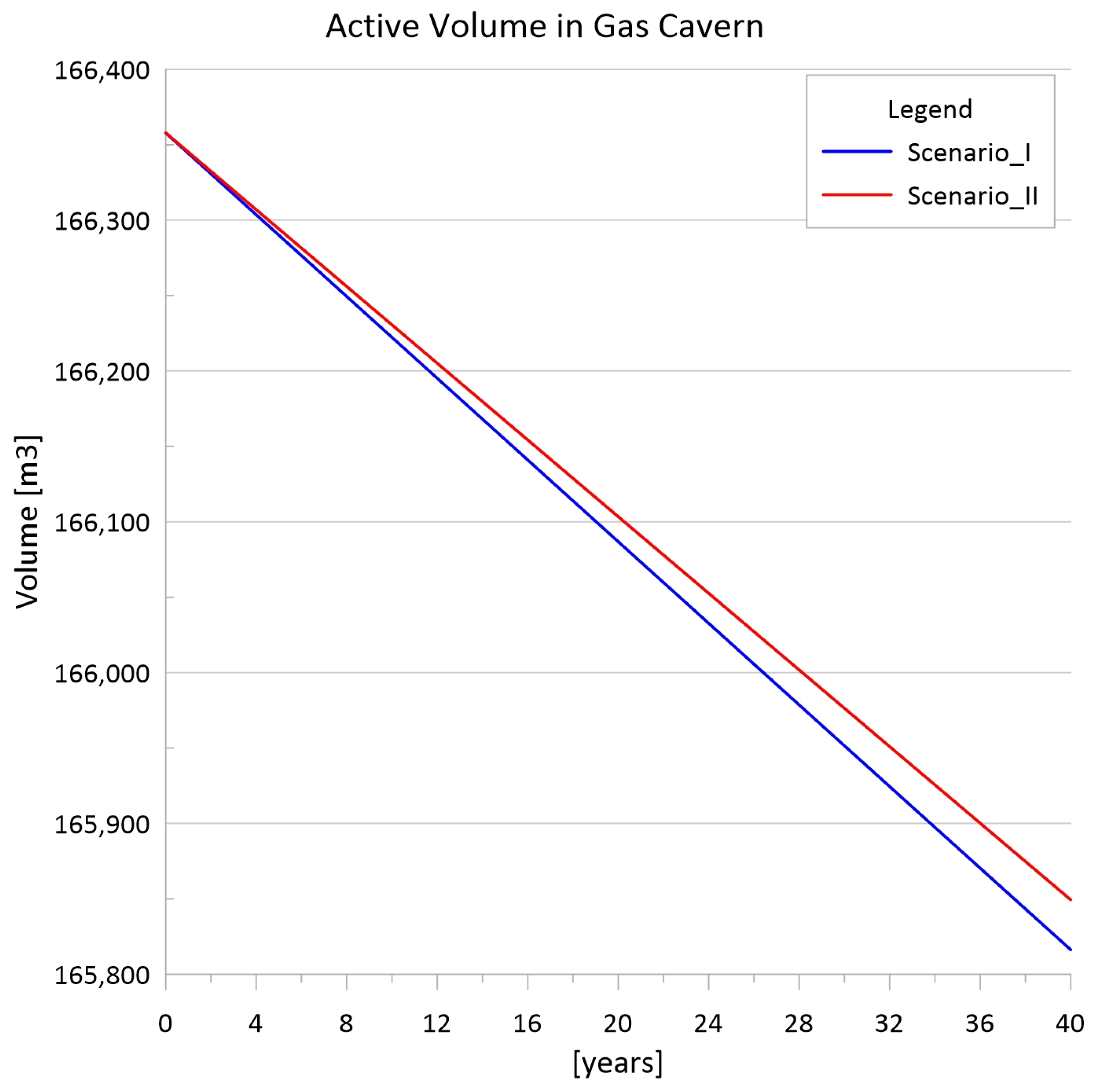

Figure 6.

Decrease in the active volume of the natural gas cavern over 40 years of operation.

In the case of the CAES cavern (Figure 4 and Figure 5), it is clearly visible that the smallest loss of volume occurs in the case of scenario I. It follows that the daily operation of the storage is, in this respect, the most advantageous for this type of cavern. In the other scenarios, we are dealing with slightly larger losses of active volume over 40 years of storage operation (in these three variants, the losses are similar). However, it should be clearly noted that the differences between the most and least advantageous variants do not exceed 20 m3.

For the natural gas cavern (Figure 6), scenario II is more advantageous due to the smaller decrease in active volume over 40 years of storage operation. However, it should be clearly noted that the differences between both scenarios of gas cavern operation adopted for analysis do not exceed 50 m3 of active volume.

The differences in the obtained average annual convergence speed between CAES and natural gas caverns result primarily from different maximum and minimum pressures and operating scenarios of individual caverns. The period when the cavern remains empty at pressure pmin has the greatest impact on the volume loss. Hence, the most important thing in designing storage operating scenarios is to shorten this period to a minimum.

5. Conclusions

The calculations carried out in the article confirmed the technical possibility of cooperation of CAES installations with natural gas storage caverns in terms of small volume loss in the case of their continuous use for balancing the power grid.

The loss of active cavern capacity due to the convergence phenomenon is one of the key problems that arise during the operation of storage caverns in rock salt deposits.

With a relatively large operating regime of the CAES storage cavern (4 h of emptying) and the adopted operating scenarios of 24 h, 2 days, 1 week, and 2 weeks, no significant decreases in the active volume of the storage were observed after 40 years of operation, the difference between the individual variants of the operating scenarios reached a maximum of 20 m3.

In the case of the CUGS storage cavern, emptying the cavern from maximum to minimum pressure will take 30 days, and depending on the scenario, the filling time will be 60 or 120 days; the observed difference does not exceed 50 m3 of the active volume.

The differences in the obtained mean annual convergence speeds between the CAES and CUGS caverns are primarily due to the different operating pressure ranges but also to different operating scenarios.

The period when the cavern remains empty has the greatest impact on the loss of volume. The most important thing is to shorten this period to a minimum.

The analyses and calculations carried out indicate that the large-scale storage of surplus electricity from RES is possible using CAES technology installations connected to natural gas storage caverns. Such an installation can operate practically every day and will not significantly affect the loss of storage capacity over the 40 years of operation of such a storage facility.

Calculations were performed on the averaged parameter values for a given location. In the case of moving to the design phase of such an installation, it would be necessary to first conduct detailed geological studies to confirm the possibility of creating caverns of a given volume.

During the stage of designing the installation, attention should also be paid to the aspect related to the need to dispose of brine from the leaching of salt caverns. Discharging brine into surface waters is not legally permitted in Poland or in the EU. Hence, the only possibility is its injection into deep aquifers, discharging diluted brine into seawater (note by CUGS Kosakowo), or using brine as a semi-finished product in the chemical and spa industry (note by CUGS Mogilno).

The economic aspect of building and later operating such an installation will also be of key importance. At the current stage of energy transformation, economic indicators will not be promising, but as forecasts indicate, the constantly growing share of renewable energy will force the need to adapt the network by creating energy storage facilities.

In the era of the ongoing energy transformation in Poland, it is possible in the future to consider the possibility of replacing the gas turbine for electricity production with a hydrogen-powered turbine or using fuel cells instead. In such a case, natural gas storage caverns should be replaced with caverns storing hydrogen. However, such a solution requires separate analyses, taking into account the use of alkaline electrolyzers for hydrogen production, which, compared to other solutions, allows for a relatively flexible possibility of quick start-up and shutdown of the installation at any time (short-term surplus energy from renewable energy sources). Analyses should also include the need to obtain large amounts of water of appropriate purity for the production of “green hydrogen” in electrolyzers, which is often not mentioned.

Of course, in the case of large-scale energy storage, the storage of “green” hydrogen is currently being considered but it seems that in the “transitional” period, the concept proposed in the article, this type of installation will certainly prove useful in covering peak demand for energy storage from renewable sources. Moreover, in the author’s opinion, from the perspective of the next 30–35 years, it will definitely be the most advantageous solution in relation to Polish conditions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Symbols and Abbreviations

| Ak, Bk, nk, Qk | coefficients for calculating the convergence rate determined by laboratory tests |

| CAES | compressed air energy storage |

| CUGS | cavern underground gas storage |

| Dmax | maximum cavern diameter |

| G | acceleration of gravity |

| gfrac | safe fracturing gradient depending on the type of the salt deposit (in practice, it is assumed that 0.018 MPa/m +/− 0.001) |

| gstr | strength gradient |

| gT | geothermal gradient |

| H | cavern height |

| hfl | floor shelf height |

| hneck | neck height |

| hcs | ceiling shelf height |

| hup | thickness of the upper dome of the cavern (assumed 1/3 Dmax) |

| hdown | thickness of the lower dome of the cavern (assumed 1/6 Dmax) |

| hroof | depth of the deposit |

| hcem | cementation depth |

| hmid | depth of the cavern center |

| kaverage | average annual convergence speed |

| kpmax | convergence speed at maximum pressure |

| kpmin | convergence speed at minimum pressure |

| M | thickness of the deposit |

| n | number of caverns |

| P | power |

| p0 | additive constant for bedded salt deposits in Poland |

| pmax | maximum pressure |

| pmin | minimum pressure |

| p(hmid) | rock mass pressure at the depth of the center of the storage cavern |

| R | gas constant |

| RES | renewable energy sources |

| t | working time |

| Tg0 | thermal coefficient |

| Trock | temperature of the rock mass |

| V | cavern geometric volume |

| Vactive | cavern geometric active volume (storage volume) |

| ∆p | working pressure (pmax − pmin) |

| ρgas | gas density |

| ∆tmin | the time when the cavern remains at the pressure pmin |

| ∆tfill | the time when the cavern is filled to the pressure pmax |

| ∆tmax | the time when the cavern remains filled to the pressure pmax |

| ∆tempt | the time when the cavern is downloaded to the pressure pmin |

| ∆Vnm3 | storage capacity of the natural gas cavern |

| ρ | average density of overburden rocks |

| η | cavern slenderness: |

References

- Urbańczyk, K.; Ślizowski, J. An attempt to asses suitability of middle-Poland salt domes for natural gas storage. Arch. Min. Sci. 2012, 57, 335–349. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczyński, S.; Skokowski, D.H.; Włodek, T.; Polański, K. Compressed air energy storage as backup generation capacity combined with wind energy sector in Poland implementation possibilities. AGH Drill. Oil Gas 2015, 32, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- He, W.; Luo, X.; Evans, D.; Busby, J.; Garvey, S.; Parkes, D.; Wang, J. Exergy storage of compressed air in cavern and cavern volume estimation of the large-scale compressed air energy storage system. Appl. Energy 2017, 208, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotogino, F. Compressed Air Storage. In Proceedings of the First International Renewable Energy Storage (IRES I) Conference, Gelsenkirchen, Germany, 30–31 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Robb, D. The CAES for wind. Renew. Energy Focus 2011, 12, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadayon, L.; Meiers, J.; Ibing, L.; Erdelkamp, K.; Frey, G. Coordinated operation of pumped hydro energy storage with reversible pump turbine and co-located battery energy storage system. Automatisierungstechnik 2025, 73, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doppelbauer, M. Energy Storage Systems. Introduction to Electromobility; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, T.; Pang, S.; Sun, S. Thermal effects of organic porous media on absorption and desorption behaviors of carbon dioxide. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 254, 123920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berest, P.; Brouard, B.; Jafari, M.K.; Sambeek, L.V. Thermomechanical aspects of high frequency cyclic in salt storage caverns. In Proceedings of the International Gas Union Research Conference, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 19–21 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Berest, P.; Brouard, B.; Djakeun-Djizanne, H.; Hevin, G. Thermomechanical effects of a rapid depressurization in a gas cavern. Acta Geotech. 2013, 9, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berest, P.; Djizanne, H.; Brouard, B.; Hevin, G. Rapid depressurization: Can they lead to irreversible damage? In Proceedings of the SMRI Conference, Regina, SK, Canada, 23–24 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Raju, M.; Khaitan, S.K. Modeling and simulation of compressed air storage in caverns: A case study of the Huntorf plant. Appl. Energy 2012, 89, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślizowski, J.; Urbańczyk, K.; Lankof, L.; Serbin, K. Selection of Possible Locations of Underground Storage Tanks for Energy Storage in the Form of Compressed Air from the Point of View of the Use Underground Geological Structures in the Indicated Areas of Poland; IGSMiE PAN: Cracow, Poland, 2011; Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Czapowski, G.; Aleksandrowski, P.; Jarosiński, M. Struktury solne. In Atlas Geologiczny Polski; Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny–Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tomczyk, A.M.; Bednorz, E. Atlas klimatu Polski (1991–2020); Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- GSF Kawerna. Available online: https://ipi.gasstoragepoland.pl/en/menu-en/transparency-template/?page=services-and-facilities/technical-characteristics/gsf-kawerna/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Polański, K. Influence of the Variability of Compressed Air Temperature on Selected Parameters of the Deformation-Stress State of the Rock Mass Around a CAES Salt Cavern. Energies 2021, 14, 6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, K.-H.; Hou, Z.; Düsterloh, U. Some New Aspects in Modelling of Cavern Behavior and Safety Analysis. In Proceedings of the SMRI Meeting, Rome, Italy, 4–7 October 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ślizowski, J.; Urbańczyk, K. Możliwości Magazynowania Gazu Ziemnego w Polskich Złożach Soli Kamiennej w Zależności od Warunków Geologiczno-Górniczych; IGSMiE PAN: Kraków, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.Y.; Wu, J.L. Optimal sizing of the CAES system in a power system with high wind power penetration. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2012, 37, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, P.; Wang, F. A simplified and unified analytical solution for temperature and pressure variations in compressed air energy storage caverns. Renew. Energy 2015, 74, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaledi, K.; Mahmoudi, E.; Datcheva, M.; Schanz, T. Analysis of compressed air storage caverns in rock salt considering thermo-mechanical cyclic loading. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślizowski, J. Geomechaniczne Podstawy Projektowania Komór Magazynowych Gazu Ziemnego w Złożach soli Kamiennej; Wydawnictwo IGSMiE PAN: Kraków, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).