Power Transformers Cooling Design: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

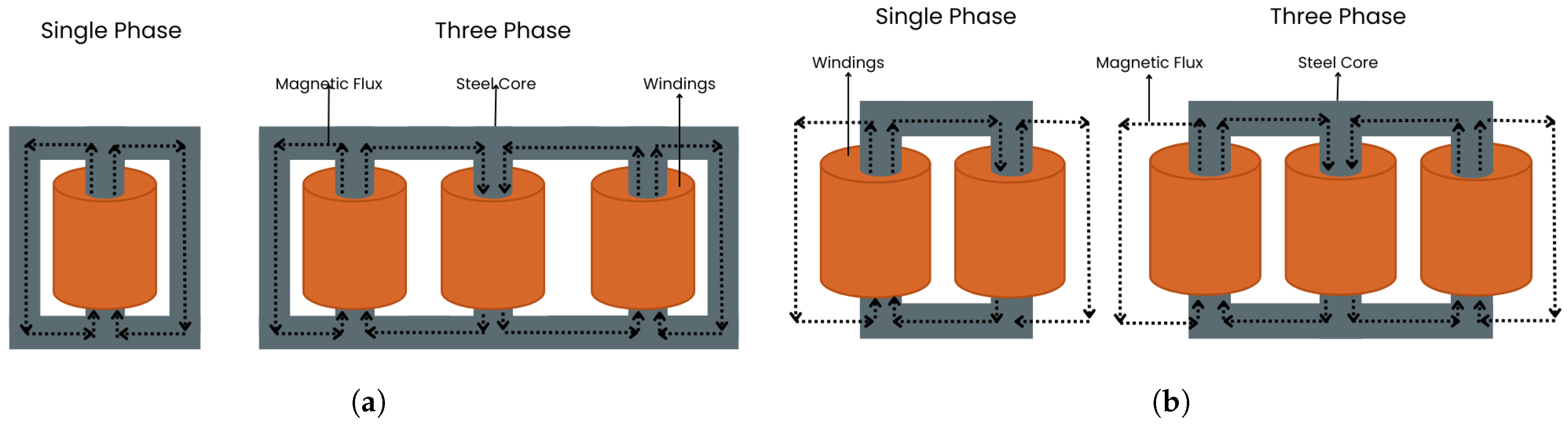

3. Power Transformers

3.1. Heat Generation in Transformers Windings

3.2. Transformers Oils: Types and Properties

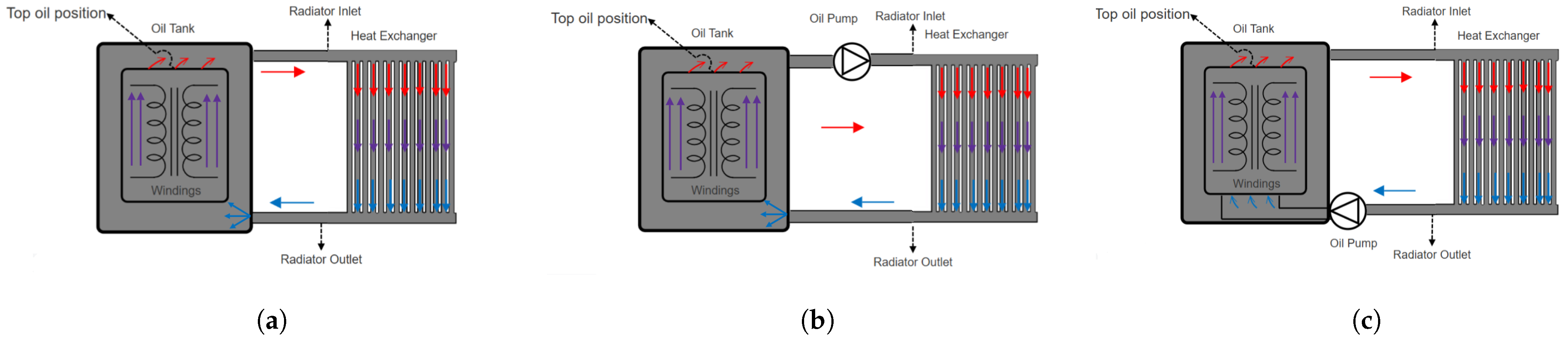

3.3. Oil Circulation Systems and Cooling Methods

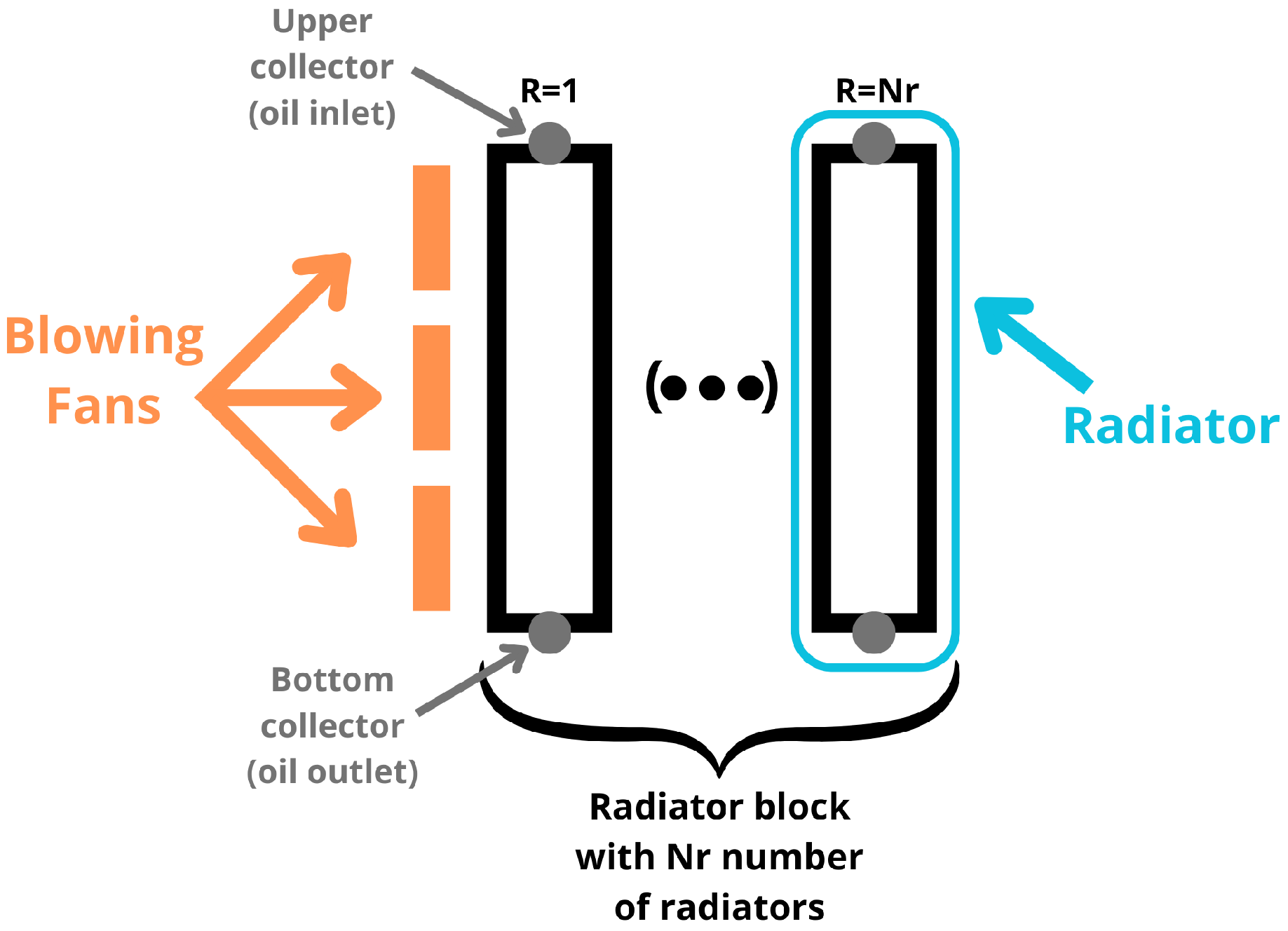

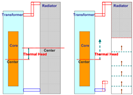

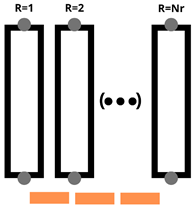

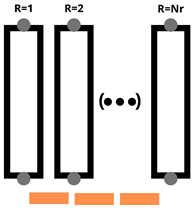

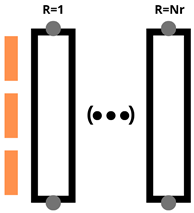

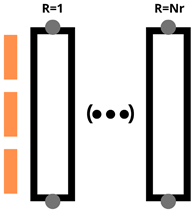

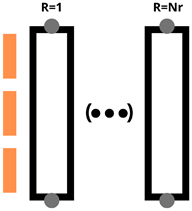

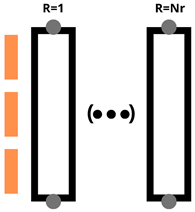

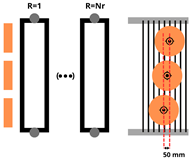

4. Radiator Systems

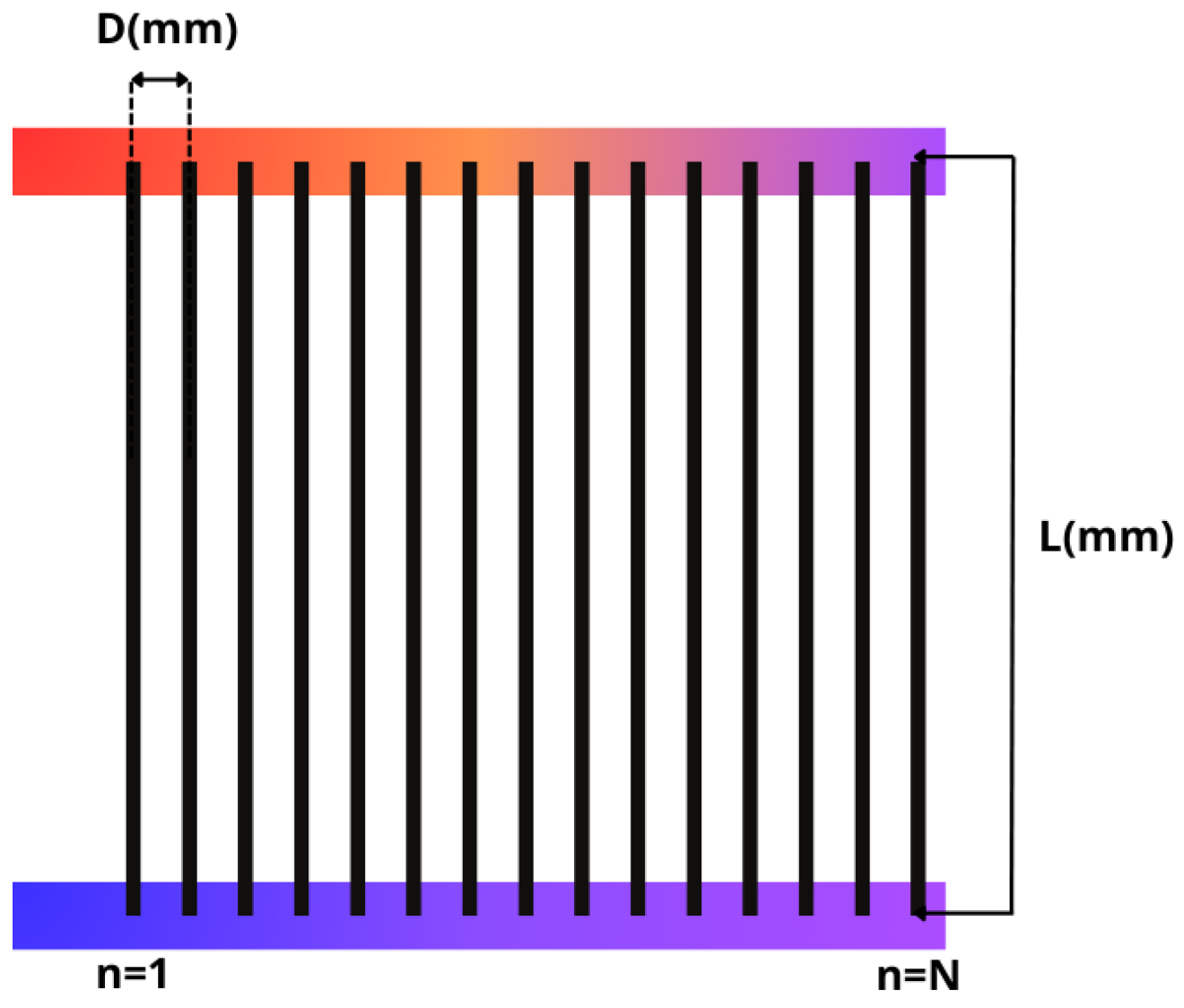

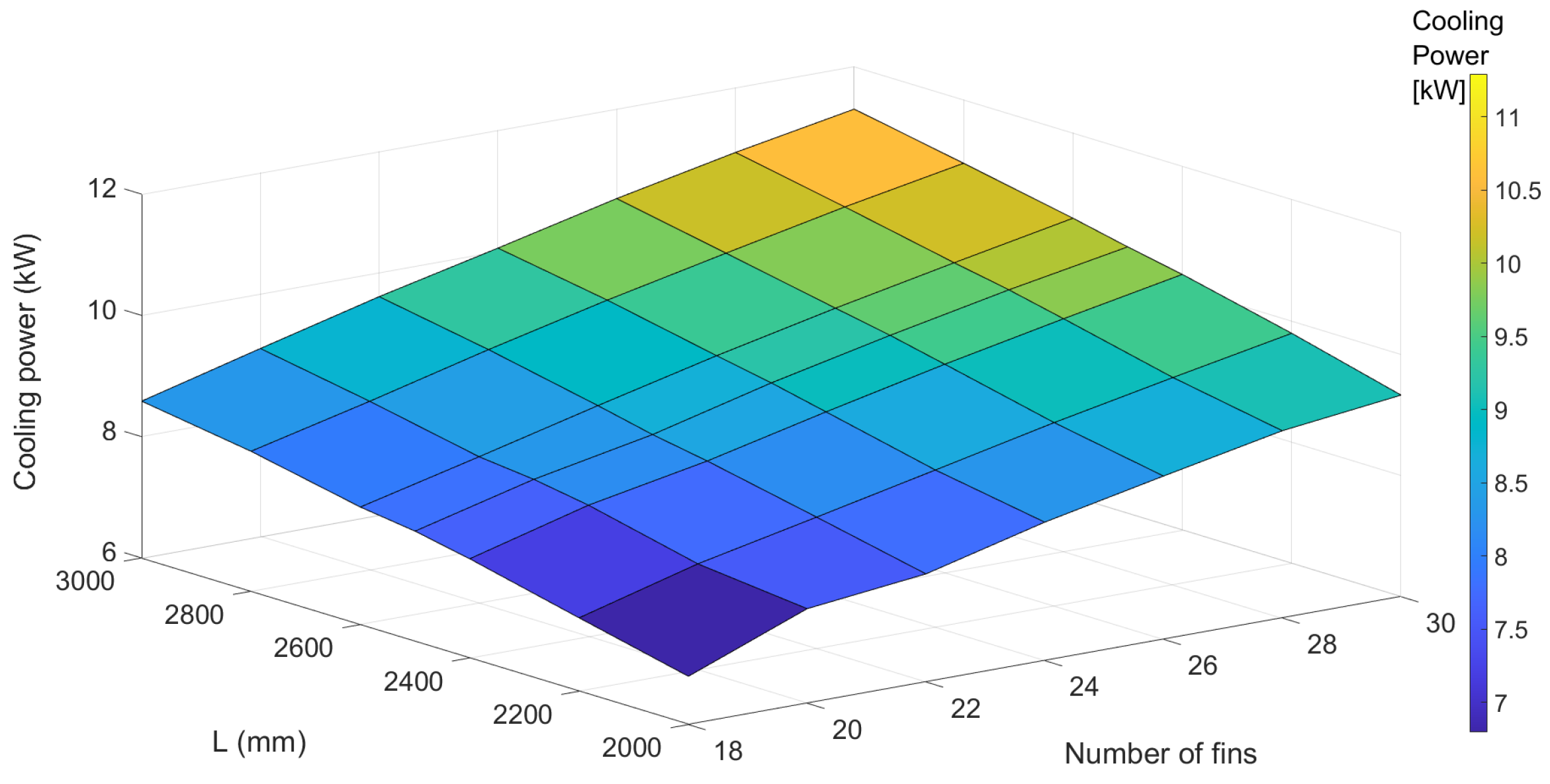

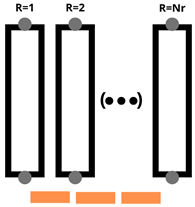

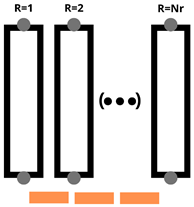

4.1. Effect of Dimensions on Radiator Performance

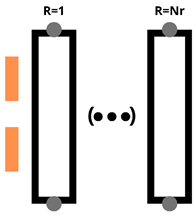

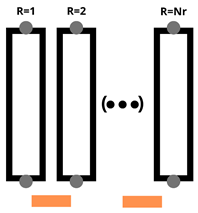

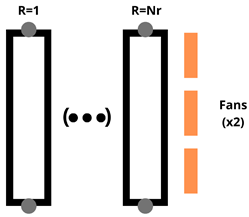

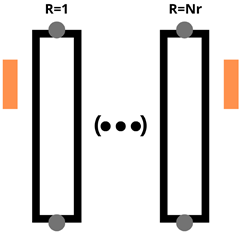

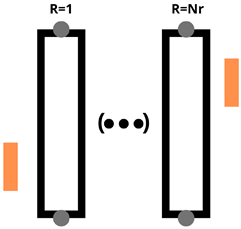

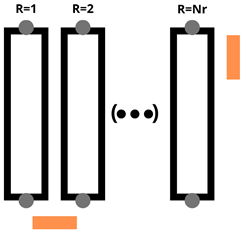

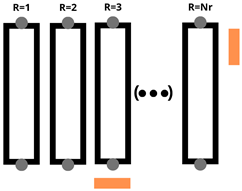

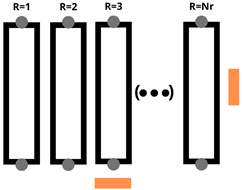

4.2. Optimal Placement and Configuration of Radiators

4.3. Techniques to Enhance Oil Cooling Efficiency

4.3.1. Ventilation Design: Fan Types, Placement, and Airflow Dynamics

Factor of Merit

Oil Flow Rate and Fan Speed Management

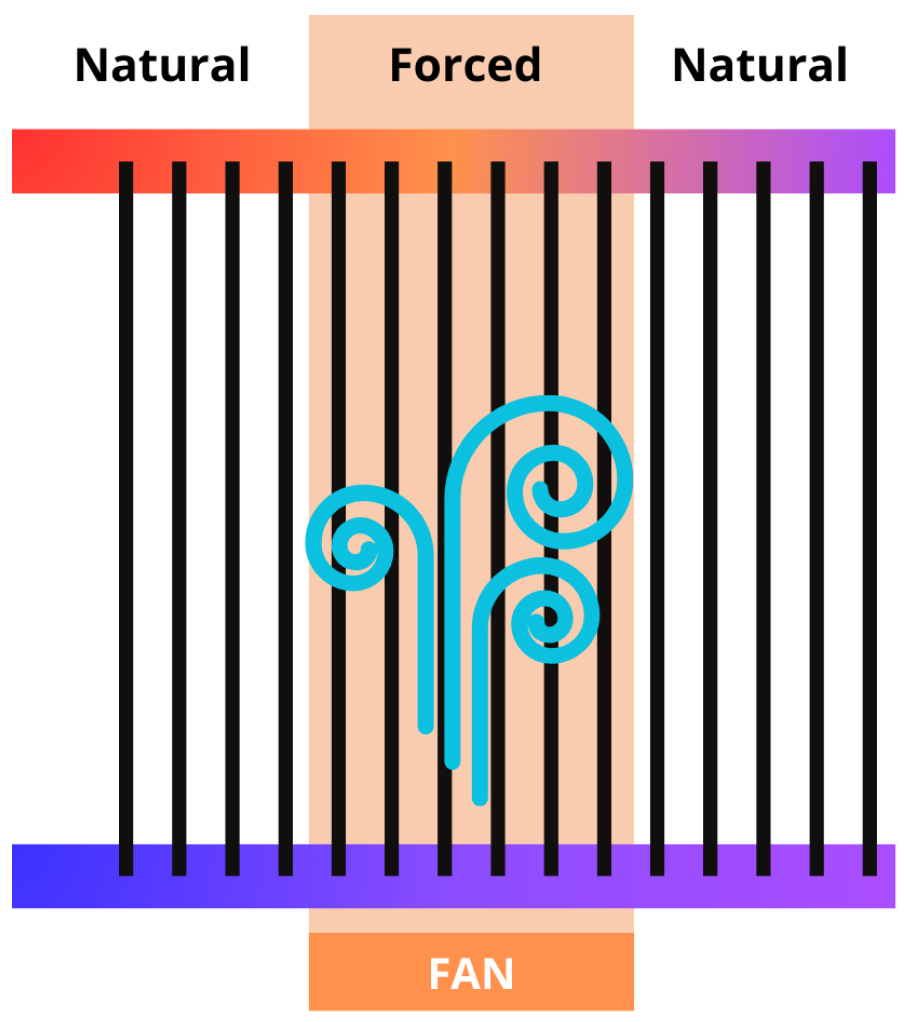

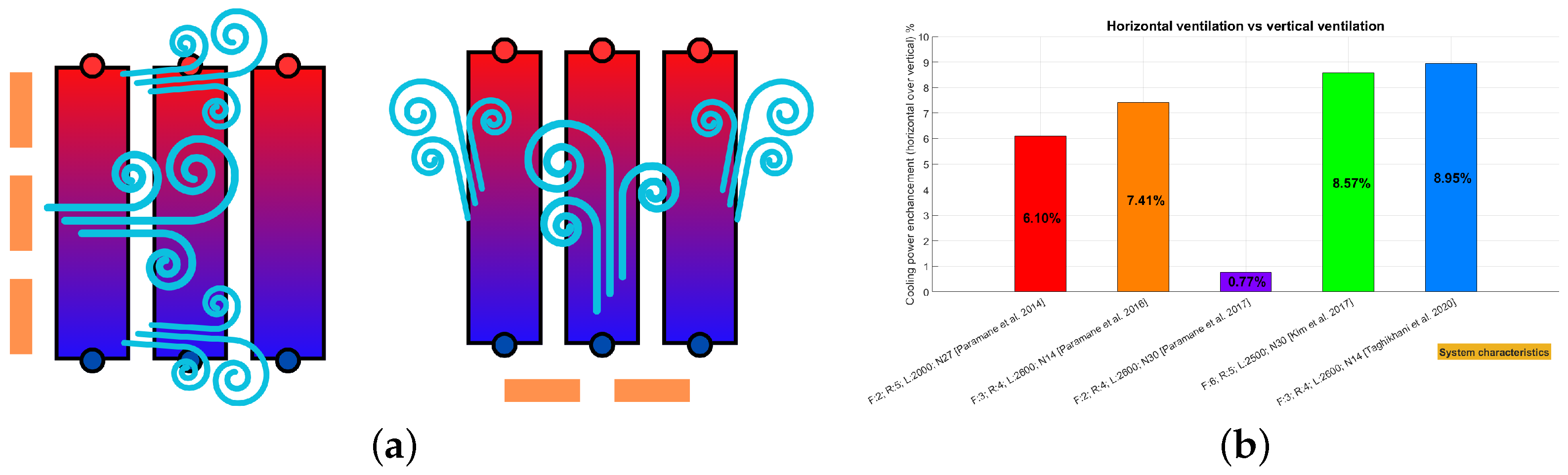

Only Directional Ventilation: Horizontal vs. Vertical

Not-Only Directional Ventilation

Offset Between Fans Centres

Fan Speed and Diameter

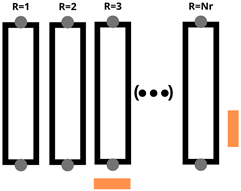

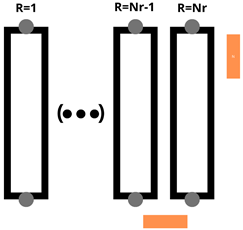

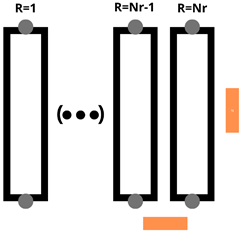

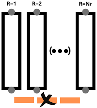

Fan Malfunction

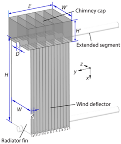

4.3.2. Passive Cooling Strategies for Improved Performance

5. Radiator Modelling Approaches

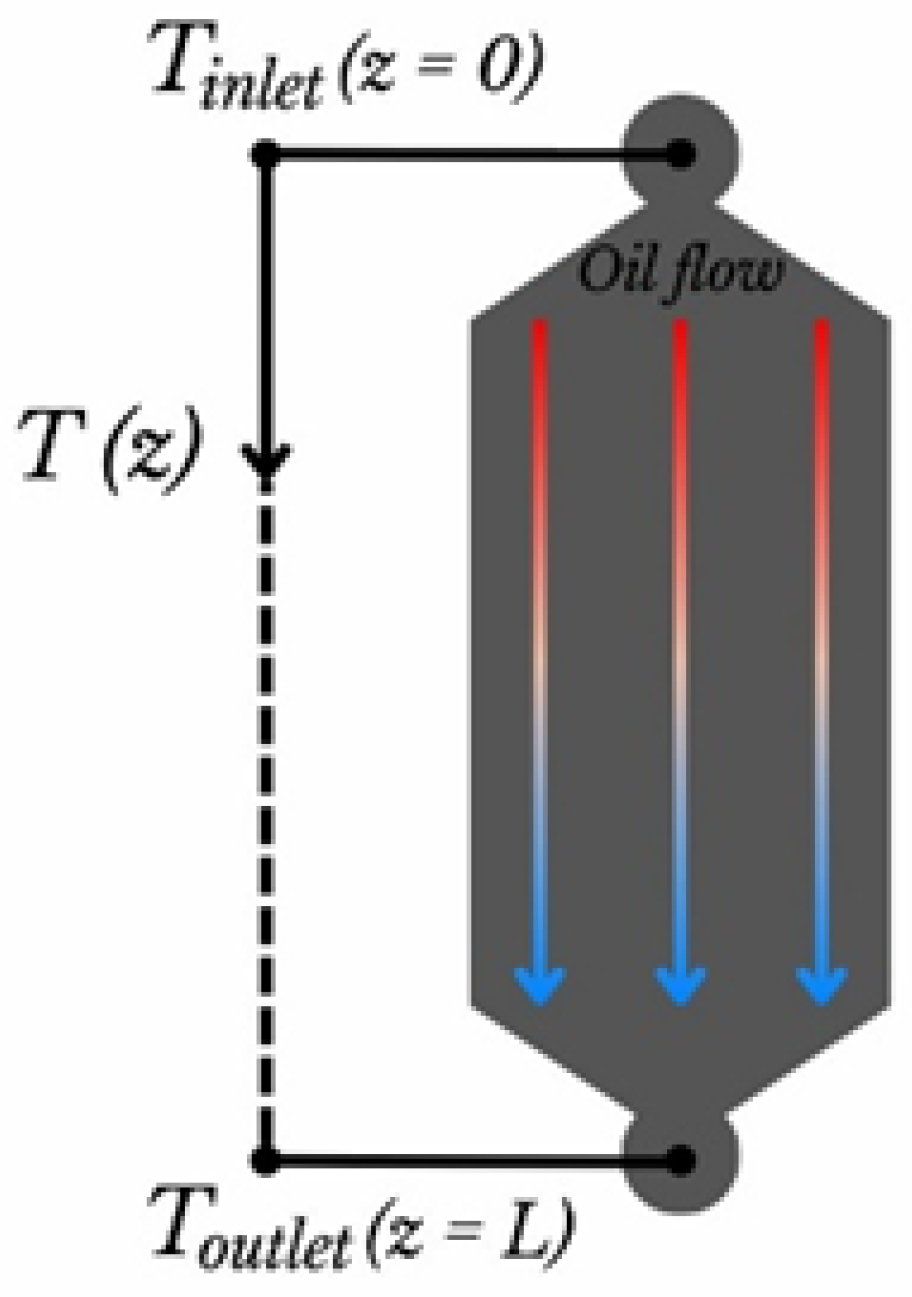

5.1. Analytical Modelling Techniques

5.2. Numerical Simulation Approaches

5.3. Experimental Validation and Testing

5.4. AI/Neural Networks

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koca, A.; Senturk, O.; Ömer, A.; Özcan, H. Techno-Economic Optimization of Radiator Configurations in Power Transformer Cooling. Designs 2024, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Jeong, M.; Park, Y.G.; Ha, M.Y. A numerical study of the effect of a hybrid cooling system on the cooling performance of a large power transformer. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 136, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S. The first step towards energy revolution. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2019, 21, 227–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telles, A.; Morera-Hernández, M.; Eneldo López-Monteagudo, F.; Villela-Varela, R. Prospectiva de las energías eólica y solar fotovoltaica en la producción de energía eléctrica. CienciaUAT 2017, 11, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Rathore, K. Renewable Energy for Sustainable Development Goal of Clean and Affordable Energy. Int. J. Mater. Manuf. Sustain. Technol. 2023, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M.W.; Stanić, Z. The Role of Renewable Energy Sources in Future Electricity Supply. J. Energy-Energija 2006, 55, 292–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Peng, W.; Adumene, S.; Yazdi, M. Attention Towards Energy Infrastructures: Challenges and Solutions. In Intelligent Reliability and Maintainability of Energy Infrastructure Assets; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chang, Y.; Lu, B. A review of temperature prediction methods for oil-immersed transformers. Measurement 2025, 239, 115383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Kim, D.; Abu-Siada, A.; Kumar, S. Oil-Immersed Power Transformer Condition Monitoring Methodologies: A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, L.H.; Oliveira, M.M.; Beltrame, R.C.; Bender, V.C.; Marchesan, T.B.; Marin, M.A. Thermal Experimental Evaluation of a Power Transformer Under OD/OF/ON Cooling Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2023 15th Seminar on Power Electronics and Control, SEPOC 2023, Santa Maria, Brazil, 22–25 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.E.; Poyrazoglu, G.; Celikpence, M.; Keles, M.; Kozalioglu, S.; Sevim, Y. Enhancing Energy Efficiency in Distribution Grids through Load Profile-Driven Mutual Displacement of Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th Global Power, Energy and Communication Conference (GPECOM), Budapest, Hungary, 4–7 June 2024; pp. 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Ma, N.; Li, B.; He, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S. Analysis of the Influence of Insulation Oil Type on Temperature Rise of Oil-immersed Power Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th Asia Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering (ACPEE), Shanghai, China, 11–13 April 2024; pp. 1968–1972. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Lin, B.; Zhang, H.; Huo, W.; Deng, H.; Liu, G. Analysis of external heat dissipation enhancement of oil-immersed transformer based on falling film measure. Therm. Sci. 2022, 26 Pt A, 4519–4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsili, M.A.; Amoiralis, E.I.; Kladas, A.G.; Souflaris, A.T. Power transformer thermal analysis by using an advanced coupled 3D heat transfer and fluid flow FEM model. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2012, 53, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.c.; Xiao, C.; Hou, J.; Kong, L.; Ye, J.; Yu, W.j. Analysis of Factors Affecting Temperature Rise of Oil-immersed Power Transformer. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1639, 012087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yao, W.; Gao, X.; Ren, Y. Temperature simulation of oil-immersed transformerbased on fluid-thermal coupling. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2503, 012060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Ding, Y.; Wang, T.; Wen, T.; Zhang, Q. Study on bubble evolution in oil-paper insulation during dynamic rating in power transformers. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Power Modulator and High Voltage Conference (IPMHVC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 6–9 July 2016; pp. 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletti, B.; Blaszczyk, A.; Wu, W. CFD Based Sensitivity Study of Cooling Performance of Transformer Radiators. In Proceedings of the 2019 6th International Advanced Research Workshop on Transformers (ARWtr), Cordoba, Spain, 7–9 October 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, Q.; Wilkinson, M.; Wilson, G.; Wang, Z. A Reduced Radiator Model for Simplification of ONAN Transformer CFD Simulation. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2022, 37, 4007–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Si, W.; Fu, C.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, P.; Yang, J.; Wang, Q. Numerical Study on Hydrodynamic and Heat Transfer Performances for Panel-Type Radiator of Transformer Using the Chimney Effect. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2023, 103, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorte, S.; Martins, N.; Oliveira, M.S.A.; Vela, G.L.; Relvas, C. Unlocking the Potential of Wind Turbine Blade Recycling: Assessing Techniques and Metrics for Sustainability. Energies 2023, 16, 7624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 60076-8:1997; Power Transformers—Part 8: Loading Guide for Oil-Immersed Power Transformers. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 1997.

- Gautam, S.P.; Kedia, S.; Bahirat, H.J.; Shukla, A. Design Considerations for Medium Frequency High Power Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Power Electronics, Drives and Energy Systems (PEDES), Chennai, India, 18–21 December 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.; Poulin, B.; Feghali, P.; Shah, D.; Ahuja, R. Transformer Design Principles, 3rd ed.; CRC press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 1–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Razi, S.; Farahani, H.; Khodakarami, A. Finite Element Analysis of Leakage Inductance of 3-Phase Shell-Type and Core Type Transformers. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2012, 4, 1721–1728. [Google Scholar]

- Lambada, P.; Wang, X. Design Optimization of Single-Phase Core-Type Transformers with Geometric Programming. In Power, Energy and Electrical Engineering; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std C57.91-2011 (Revision of IEEE Std C57.91-1995); IEEE Guide for Loading Mineral-Oil-Immersed Transformers and Step-Voltage Regulators. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 1–123. [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std. C57.12.00-2015; IEEE Standard for General Requirements for Liquid-Immersed Distribution, Power, and Regulating Transformers. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015.

- IEEE Std C57.12.90-2021 (Revision of IEEE Std C57.12.90-2015); IEEE Standard Test Code for Liquid-Immersed Distribution, Power, and Regulating Transformers. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–119. [CrossRef]

- Novkovic, M.; Radakovic, Z.; Torriano, F.; Picher, P. Proof of the Concept of Detailed Dynamic Thermal-Hydraulic Network Model of Liquid Immersed Power Transformers. Energies 2023, 16, 3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozovska, K.; Hilber, P. Study of the Monitoring Systems for Dynamic Line Rating. Energy Procedia 2017, 105, 2557–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallnerström, C.J.; Hilber, P.; Söderström, P.; Saers, R.; Hansson, O. Potential of dynamic rating in Sweden. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Probabilistic Methods Applied to Power Systems (PMAPS), Durham, UK, 7–10 July 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, A.A.; Abdali, A.; Taghilou, M.; Haes Alhelou, H.; Mazlumi, K. Investigation of Mineral Oil-Based Nanofluids Effect on Oil Temperature Reduction and Loading Capacity Increment of Distribution Transformers. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 4325–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std C57.100-1999; IEEE Standard Test Procedure for Thermal Evaluation of Liquid-Immersed Distribution and Power Transformers. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 1–17. [CrossRef]

- IEC 60076-7:2005; Power Transformers—Part 7: Loading Guide for Oil-Immersed Power Transformers. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- Najdenkoski, K.; Rafajlovski, G.; Dimcev, V. Thermal Aging of Distribution Transformers According to IEEE and IEC Standards. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Power Engineering Society General Meeting, Tampa, FL, USA, 24–28 June 2007; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isha, M.T.; Wang, Z. Transformer hotspot temperature calculation using IEEE loading guide. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference on Condition Monitoring and Diagnosis, Beijing, China, 21–24 April 2008; pp. 1017–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 60076; Power Transformers. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Jalal, T.S.; Rashid, N.; van Vliet, B. Implementation of Dynamic Transformer Rating in a distribution network. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Power System Technology (POWERCON), Auckland, New Zealand, 30 October–2 November 2012; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, S.; Taheri, H.; Fofana, I.; Hemmatjou, H.; Gholami, A. Effect of power system harmonics on transformer loading capability and hot spot temperature. In Proceedings of the 2012 25th IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE), Montreal, QC, Canada, 29 April–2 May 2012; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, D.; Koo, K.; WOO, J.W.; Kwak, J.S. A Study on the Hot Spot Temperature in 154kV Power Transformers. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2012, 7, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, M.; Sharma, S.R.; Singh, A.; Kumar, R.; Sood, Y.R. An Improved Infrared Thermography Techique for Hotspot Temperature, Per Unit Life and Aging Accelerating Factor Computation in Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Computing, Power and Communication Technologies (GUCON), Greater Noida, India, 2–4 October 2020; pp. 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utami, N.; Tamsir, Y.; Pharmatrisanti, A.; Gumilang, H.; Cahyono, B.; Siregar, R. Evaluation condition of transformer based on infrared thermography results. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE 9th International Conference on the Properties and Applications of Dielectric Materials, Harbin, China, 19–23 July 2009; pp. 1055–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betta, G.; Pietrosanto, A.; Scaglione, A. An enhanced fiber-optic temperature sensor system for power transformer monitoring. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2001, 50, 1138–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoop, S.; Naufal, N. Monitoring of winding temperature in power transformers—A study. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Instrumentation and Control Technologies (ICICICT), Kannur, Kerala, India, 6–7 July 2017; pp. 1334–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, A.; Kiesel, P.; Teepe, M.; Cheng, F.; Chen, Q.; Karin, T.; Jung, D.; Mostafavi, S.; Smith, M.; Stinson, R.; et al. Low-Cost Embedded Optical Sensing Systems For Distribution Transformer Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2021, 36, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; MacAlpine, J.; Chan, C.; Jin, W.; Zhang, M.; Liao, Y. A novel wavelength detection technique for fiber Bragg grating sensors. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2002, 14, 678–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiming, H.; Yifan, Z.; Yi, J.; Mingli, F.; Guoli, W.; Ran, Z.; Qiao, W. Study on the Influence of Harmonics on the Magnetic Leakage Field and Temperature Field of 500 kV Connected Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Conference on Electrical Materials and Power Equipment (ICEMPE), Guangzhou, China, 7–10 April 2019; pp. 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saric, M.; Hivziefendic, J.; Vuic, L. Analysis and Control of DG Influence on Voltage Profile in Distribution Network. In International Symposium on Innovative and Interdisciplinary Applications of Advanced Technologies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, L.; Wen, H.; Liu, C.; Hao, J.; Li, Z. Simulation Analysis of the Influence of Harmonics Current on the Winding Temperature Distribution of Converter Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th Asia Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering (ACPEE), Chongqing, China, 8–11 April 2021; pp. 1566–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdali, A.; Mazlumi, K.; Rabiee, A. Harmonics impact on hotspot temperature increment of distribution transformers: Nonuniform magnetic-thermal approach. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 157, 109826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeisian, L.; Niazmand, H.; Ebrahimnia-Bajestan, E.; Werle, P. Thermal management of a distribution transformer: An optimization study of the cooling system using CFD and response surface methodology. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 104, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Ruan, J.; Quan, Y.; Gong, R.; Huang, D.; Duan, C.; Xie, Y. A Method for Hot Spot Temperature Prediction of a 10 kV Oil-Immersed Transformer. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 107380–107388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rommel, D.; Di Maio, D.; Tinga, T. Transformer hot spot temperature prediction based on basic operator information. INternational J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 124, 106340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xu, G.; Li, N.; Li, K.; Liang, Y.; Zhong, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, P. Hotspot Temperature Prediction of Dry-Type Transformers Based on Particle Filter Optimization with Support Vector Regression. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez-Balderas, E.A.; Medina-Marin, J.; Olivares-Galvan, J.C.; Hernandez-Romero, N.; Seck-Tuoh-Mora, J.C.; Rodriguez-Aguilar, A. Hot-Spot Temperature Forecasting of the Instrument Transformer Using an Artificial Neural Network. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 164392–164406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J.; Zhao, T.; Zou, L.; Wang, X. A New Prediction Model for Transformer Winding Hotspot Temperature Fluctuation Based on Fuzzy Information Granulation and an Optimized Wavelet Neural Network. Energies 2017, 10, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.; Lemos, A.; Caminhas, W.; Boaventura, W. Thermal modeling of power transformers using evolving fuzzy systems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2012, 25, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, A.; García, D.; García, B.; Burgos, J.C. A comparative study on the dielectric properties of mineral oils and natural esters. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2023 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC/I&CPS Europe), Madrid, Spain, 6–9 June 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oparanti, S.O.; Rao, U.M.; Fofana, I. Natural Esters for Green Transformers: Challenges and Keys for Improved Serviceability. Energies 2023, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesewetter, D.V.; Reznik, A.S.; Zhuravleva, N.M.; Litvinov, D.V. Research of Dielectric Properties of the Mixtures of Petroleum Transformer Oils and Silicone Liquids. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Conference of Russian Young Researchers in Electrical and Electronic Engineering (ElConRus), St. Petersburg, Moscow, Russia, 26–29 January 2021; pp. 1224–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). Fluids for Electrotechnical Applications—Mineral Insulating Oils for Electrical Equipment; International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Chen, R.; Hu, X.; Xu, X.; Xu, Y. Dielectric and physicochemical properties of mineral and vegetable oils mixtures. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 19th International Conference on Dielectric Liquids (ICDL), Manchester, UK, 25–29 June 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombek, G.; Gielniak, J. Fire safety and electrical properties of mixtures of synthetic ester/mineral oil and synthetic ester/natural ester. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2018, 25, 1846–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidik, N.A.C.; Mohammed, H.; Alawi, O.A.; Samion, S. A review on preparation methods and challenges of nanofluids. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2014, 54, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, M.; Lv, Y.; Li, C. A Review on Properties, Opportunities, and Challenges of Transformer Oil-Based Nanofluids. J. Nanomater. 2016, 2016, 8371560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.J.; Halim, M.A.; Roy, P.; Sahjahan. Moisture Withstand Capability of Natural Ester Based Dielectric Oils for Power Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2023 10th IEEE International Conference on Power Systems (ICPS), Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 13–15 December 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdali, A.; Abedi, A.; Mazlumi, K.; Rabiee, A.; Guerrero, J.M. Precise thermo-fluid dynamics analysis of corrugated wall distribution transformer cooled with mineral oil-based nanofluids: Experimental verification. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 221, 119660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altay, R.; Santisteban, A.; Olmo, C.; Delgado, F.; Renedo, C.J.; Köseoğlu, A.; Ortiz, A. Performance analysis of natural, synthetic and mineral oil in a 100 MVA power transformer. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Dielectrics (ICD), Valencia, Spain, 5–31 July 2020; pp. 770–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Dai, W.; Zhuo, R.; Peng, Q.; Gao, M.; Zou, D.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, X. Numerical Calculation and Analysis of Temperature Rise in Power Transformers with Different Insulating Liquids. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Electrical Insulation Conference (EIC), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–5 June 2024; pp. 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Ha, M.Y. A study on the performance of different radiator cooling systems in large-scale electric power transformer. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2017, 31, 3317–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, G.C.; Medeiros, L.H.; Oliveira, M.M.; Barth, N.D.; Bender, V.C.; Marchesan, T.B.; Falcão, C.E. Thermal Analysis of Power Transformers with Different Cooling Systems Using Computational Fluid Dynamics. J. Control. Autom. Electr. Syst. 2022, 33, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, L.; Huebner, R.; Trevizoli, P. Numerical Evaluation of the Directed Oil Cooling System of a Mobile Power Transformer. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2023, 46, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santisteban, A.; Piquero, A.; Ortiz, F.; Delgado, F.; Ortiz, A. Thermal Modelling of a Power Transformer Disc Type Winding Immersed in Mineral and Ester-Based Oils Using Network Models and CFD. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 174651–174661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, S.; Ferreira, E.; Sá, D.; Corte-Real, C.; Lima, P.; Castro Lopes, R.; Costa, A.; Sá, C.; Monteiro, P.; Soares, M. Comparison of the Thermal Performance of Mineral Oil and Natural Ester for Safer Eco-Friendly Power Transformers A Numerical and Experimental Approach. Renew. Energy Power Qual. J. 2021, 19, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorgic, M.; Radakovic, Z. Oil-Forced Versus Oil-Directed Cooling of Power Transformers. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2010, 25, 2590–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Ryu, J. A Study on Optimizing Cooling Design for a Power Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2023 29th International Workshop on Thermal Investigations of ICs and Systems (THERMINIC), Budapest, Hungary, 27–29 September 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.g.; Cho, S.; Kim, J.K. Prediction and evaluation of the cooling performance of radiators used in oil-filled power transformer applications with non-direct and direct-oil-forced flow. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2013, 44, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garelli, L.; Ríos Rodriguez, G.; Storti, M.; Granata, D.; Amadei, M.; Rossetti, M. Reduced model for the thermo-fluid dynamic analysis of a power transformer radiator working in ONAF mode. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 124, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramane, S.B.; Joshi, K.; Van der Veken, W.; Sharma, A. CFD Study on Thermal Performance of Radiators in a Power Transformer: Effect of Blowing Direction and Offset of Fans. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2014, 29, 2596–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Jin, S.; Shou, Y.; Yuan, P.; Tian, Y.; Yang, J. Numerical study of cooling performance augmentation for panel-type radiator under the chimney effect. Therm. Sci. 2024, 28, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorella, J.; Storti, B.; Rios, G.; Storti, M. Enhancing Heat Transfer in Power Transformer Radiators via Thermo-Fluid Dynamic Analysis with Periodic Thermal Boundary Conditions. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 222, 125142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca, A.; Senturk, O.; Çolak, A.B.; Bacak, A.; Dalkilic, A.S. Artificial neural network-based cooling capacity estimation of various radiator configurations for power transformers operated in ONAN mode. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 50, 102515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wilkinson, M.; Daghrah, M.; Wilson, G.; Van Schaik, E. An Improved Analytical Method for Radiator Thermal Modelling of Natural Cooled Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on High Voltage Engineering and Applications (ICHVE), Chongqing, China, 25–29 September 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 60076-22-2:2019; Power Transformers—Part 22-2: Power Transformer and Reactor Fittings—Removable Radiators. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Anishek, S.; Sony, R.; Kumar, J.J.; Kamath, P.M. Performance Analysis and Optimisation of an Oil Natural Air Natural Power Transformer Radiator. Procedia Technol. 2016, 24, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S. An innovative method for cooling oil-immersed transformers by Rayleigh-Bénard convection. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE PES T&D Conference and Exposition, Chicago, IL, USA, 14–17 April 2014; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, C.H.; Kim, J.K.; Kweon, K.Y. Investigation of the thermal head effect in a power transformer. In Proceedings of the 2009 Transmission & Distribution Conference & Exposition: Asia and Pacific, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 26–30 October 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janic, Z.; Gavrilov, N.; Roketinec, I. Influence of Cooling Management to Transformer Efficiency and Ageing. Energies 2023, 16, 4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zuo, W.; Yang, Z.X.; Cai, Z.; Ma, P.; Ye, Z. CFD-Based Heat Dissipation Efficiency Monitoring for Radiator in Different Air-Cooling Modes. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on System Reliability and Safety, ICSRS 2021, Palermo, Italy, 24–26 November 2021; pp. 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, G.R.; Garelli, L.; Storti, M.; Granata, D.; Amadei, M.; Rossetti, M. Numerical and experimental thermo-fluid dynamic analysis of a power transformer working in ONAN mode. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 112, 1271–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, G.; Lin, B.; Deng, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, P. Thermal evaluation optimization analysis for non-rated load oil-natural air-natural transformer with auxiliary cooling equipment. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2022, 16, 3080–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djamali, M.; Tenbohlen, S. A validated online algorithm for detection of fan failures in oil-immersed power transformers. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2017, 116, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddik, M.S.; Shazly, J.; Eteiba, M.B. Thermal Analysis of Power Transformer Using 2D and 3D Finite Element Method. Energies 2024, 17, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milcă, A.S.; Dunca, G.; Pitorac, L. Numerical modelling of the cooling water system of a 106MW Hydro-Power Plant using EPANET. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1136, 012059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garakani, A.A.; Derakhshan, A. Implementing micro energy piles: A novel geothermal energy harvesting technique for enhancing foundation safety and cooling system efficiency in electric power transformers. Geothermics 2024, 123, 103097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.; Li, N.; Chen, S.; Tang, S.; Hu, Y.; Cai, J.; Lv, L.; Jin, C.; Bai, Z.; Zhong, H.; et al. Experimental study of the evaporative cooling system in a low-noise power transformer. In Proceedings of the 2012 China International Conference on Electricity Distribution, Shanghai, China, 10–14 September 2012; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Geng, M.; Liu, S.; Tang, B.; Wang, L.; Wu, J. Research on ventilation and noise reduction of indoor substation based on COMSOL Multiphysics. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 5th International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), Nangjing, China, 27–29 May 2022; pp. 3330–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hu, S.; Yang, C.; Huang, T.; Chen, W.; Tang, Q.; Cao, H.; Lu, L. Research on noise control technology of 110kV indoor substation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Big Data and Algorithms (EEBDA), Changchun, China, 24–26 February 2023; pp. 976–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Wang, L.; Zhong, H. Optimizing air inlet designs for enhanced natural ventilation in indoor substations: A numerical modelling and CFD simulation study. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 59, 104408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramane, S.B.; Veken, W.V.D.; Sharma, A. A coupled internal-external flow and conjugate heat transfer simulations and experiments on radiators of a transformer. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 103, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramane, S.B.; Veken, W.V.D.; Sharma, A.; Coddé, J. Effect of fan arrangement and air flow direction on thermal performance of radiators in a power transformer. J. Power Technol. 2017, 97, 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Taghikhani, M.A.; Afshar, M.R. Vertical and horizontal power transformer radiator fans reliability comparison in onaf cooling method. UPB Sci. Bull. Ser. D 2020, 82, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rogora, D.; Nazzari, S.; Radoman, U.; Radakovic, Z.R. Experimental Research on the Characteristics of Radiator Batteries of Oil Immersed Power Transformers. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2020, 35, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fdhila, R.B.; Kranenborg, J.; Laneryd, T.; Olsson, C.O.; Samuelsson, B.; Gustafsson, A.; Lundin, L.Å. Thermal modeling of power transformer radiators using a porous medium based CFD approach. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Computational Methods for Thermal Problems, Dalian, China, 5–7 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zuo, W.; Yang, Z.X.; Zhang, J.; Cai, Z. A Method for Fans’ Potential Malfunction Detection of ONAF Transformer Using Top-Oil Temperature Monitoring. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 129881–129889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematirad, R.; Behrang, M.; Pahwa, A. Acoustic-Based Online Monitoring of Cooling Fan Malfunction in Air-Forced Transformers Using Learning Techniques. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 26384–26400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std C57.91-1995; IEEE Guide for Loading Mineral-Oil-Immersed Transformers. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1996. [CrossRef]

- Susa, D.; Palola, J.; Lehtonen, M.; Hyvarinen, M. Temperature rises in an OFAF transformer at OFAN cooling mode in service. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2005, 20, 2517–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britter, R.; Schatzmann, M. COST 732: The model evaluation guidance and protocol document. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Computational Wind Engineering, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 23–27 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Germano, M.; Piomelli, U.; Moin, P.; Cabot, W.H. A dynamic subgrid-scale eddy viscosity model. Phys. Fluids A Fluid Dyn. 1991, 3, 1760–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandak, V.; Paramane, S.B.; Veken, W.V.d.; Codde, J. Numerical investigation to study effect of radiation on thermal performance of radiator for onan cooling configuration of transformer. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 88, 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariglino, F.; Ceresola, N.; Arina, R. External Aerodynamics Simulations in a Rotating Frame of Reference. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2014, 2014, 654037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keffer, J.F.; Shah, R.K.; Ganic, E.N. Experimental heat transfer, fluid mechanics, and thermodynamics, 1988. In Proceedings of the First World Conference on Experimental Heat Transfer, Fluid Mechanics, and Thermodynamics, Dubrovnik, Yugoslavia, 4–9 September 1988; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Saha, S.; Debnath, J.; Liu, G.; Mofijur, M.; Baniyounes, A.; Chowdhury, S.M.E.K.; Vo, D.V.N. Data-driven modelling techniques for earth-air heat exchangers to reduce energy consumption in buildings: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 4191–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Gerry, M.; Segal, D. Challenges in molecular dynamics simulations of heat exchange statistics. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 160, 074111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligus, G.; Wasilewski, M.; Kołodziej, S.; Zając, D. CFD and PIV Investigation of a Liquid Flow Maldistribution across a Tube Bundle in the Shell-and-Tube Heat Exchanger with Segmental Baffles. Energies 2020, 13, 5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.C.; Balas, V.; Perescu-Popescu, L.; Mastorakis, N. Multilayer perceptron and neural networks. WSEAS Trans. Circuits Syst. 2009, 8, 579–588. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Lu, S. Performance Analysis of Various Activation Functions in Artificial Neural Networks. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1237, 022030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, F.; Winkler, D. Bayesian Regularization of Neural Networks. In Artificial Neural Networks: Methods and Applications; Livingstone, D.J., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Analytical Methods | Numerical Methods | AI-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Examples | Thermal circuit models | FEM, CFD | Neural networks, SVR, Fuzzy logic |

| Accuracy | Moderate | High | High |

| Computational Demand | Low | High | Medium to high |

| Real-time Applicability | Good, suitable for real-time | Limited due to computational intensity | Moderate, depending on model complexity |

| Data Requirements | Low | Moderate (detailed design parameters) | High (historical data and environmental factors) |

| Implementation Complexity | Low | High (requires advanced setup) | Moderate to high |

| Cost of Deployment | Low | High | Medium |

| Typical Use Cases | Routine HST monitoring | Detailed simulation under load variations | Predictive maintenance, fault prevention |

| Limitations | Limited precision, static models | High computational demand | Dependent on data quality, computational cost |

| Fluid | Source | Property | Equation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mineral Oil | [68] | Density | |

| Conductivity | |||

| Specific Heat | |||

| Viscosity | |||

| Synthetic Ester Oil | [69] | Density | |

| Conductivity | |||

| Specific Heat | |||

| Viscosity | |||

| Natural Ester Oil | [70] | Density | |

| Conductivity | |||

| Specific Heat | |||

| Viscosity |

| Authors | Oil Circulation System | Air Circulation System | Flow Rate Radiator Inlet (m3/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| [72] | OD | AF | 0.400 (m/s) |

| [75] | AF | 25.000 × 10−3 | |

| AF | 16.667 × 10−3 | ||

| [76] | AF | 18.056 × 10−3 | |

| AF | 22.222 × 10−3 | ||

| [77] | - | 19.444 × 10−3 | |

| [73] | AF | 0.400 (m/s) | |

| AF | 0.700 (m/s) | ||

| [78] | AN | 3.300 × 10−3 | |

| AN | 4.200 × 10−3 | ||

| [10] | AN | 1.490 × 10−3 | |

| [72] | AN | 0.400 (m/s) | |

| [74] | AN | 0.250 (m/s) | |

| [72] | OF | AN | 0.400 (m/s) |

| AF | 0.400 (m/s) | ||

| [2] | AF | 0.740 × 10−3 | |

| AF | 2.210 × 10−3 | ||

| AF | 3.690 × 10−3 | ||

| AF | 5.160 × 10−3 | ||

| [10] | AN | 1.490 × 10−3 | |

| [79] | AF | 0.302 × 10−3 | |

| [80] | ON | AF | 1.700 × 10−3 |

| [78] | AN | - | |

| [10] | AN | - | |

| [74] | AN | 0.100 (m/s) | |

| [19] | AN | 0.016 × 10−3 | |

| AN | 0.022 × 10−3 | ||

| AN | 0.028 × 10−3 | ||

| AN | 0.032 × 10−3 | ||

| AN | 0.038 × 10−3 | ||

| AN | 0.041 × 10−3 | ||

| AN | 0.044 × 10−3 | ||

| [19] | AN | 0.030 × 10−3 | |

| AN | 0.040 × 10−3 | ||

| AN | 0.050 × 10−3 | ||

| AN | 0.100 × 10−3 | ||

| AN | 0.500 × 10−3 | ||

| [81] | AN | 0.157 × 10−3 | |

| [82] | AN | 0.004 × 10−3 | |

| [1,83] | AN | 0.019 × 10−3 | |

| AN | 0.031 × 10−3 | ||

| [79] | AN | 0.173 × 10−3 | |

| [80] | AN | 1.444 × 10−3 |

| Author | [°C]/ [°C] | Case | L [mm] | N | D [mm] | [°C] | Cooling Power/Cost [kW/€] | Cooling Power [kW] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [86] | 75/27 | 1 | 750 | 40 | 25.0 | - | - | 12.46 |

| 75/27 | 2 | 1500 | 20 | 45.0 | - | - | 10.91 | |

| [1] | 55/15 | 3 | 2000 | 18 | 50.0 | - | 5.72 | 6.80 |

| 55/15 | 4 | 20 | - | 5.74 | 7.56 | |||

| 55/15 | 5 | 22 | - | 5.38 | 7.78 | |||

| 55/15 | 6 | 24 | - | 5.25 | 8.28 | |||

| 55/15 | 7 | 26 | - | 5.09 | 8.69 | |||

| 55/15 | 8 | 28 | - | 4.95 | 9.09 | |||

| 55/15 | 9 | 30 | - | 4.74 | 9.33 | |||

| 55/15 | 10 | 2200 | 18 | 50.0 | - | 5.48 | 7.21 | |

| 55/15 | 11 | 20 | - | 5.31 | 7.75 | |||

| 55/15 | 12 | 22 | - | 5.09 | 8.17 | |||

| 55/15 | 13 | 24 | - | 4.92 | 8.59 | |||

| 55/15 | 14 | 26 | - | 4.77 | 9.03 | |||

| 55/15 | 15 | 28 | - | 4.62 | 9.42 | |||

| 55/15 | 16 | 30 | - | 4.49 | 9.80 | |||

| 55/15 | 17 | 2400 | 18 | 50.0 | - | 5.28 | 7.64 | |

| 55/15 | 18 | 20 | - | 5.09 | 8.17 | |||

| 55/15 | 19 | 22 | - | 4.85 | 8.55 | |||

| 55/15 | 20 | 24 | - | 4.69 | 9.00 | |||

| 55/15 | 21 | 26 | - | 4.54 | 9.44 | |||

| 55/15 | 22 | 28 | - | 4.40 | 9.84 | |||

| 55/15 | 23 | 30 | - | 4.26 | 10.22 | |||

| 55/15 | 24 | 2500 | 18 | 50.0 | - | 5.18 | 7.82 | |

| 55/15 | 25 | 20 | - | 4.96 | 8.32 | |||

| 55/15 | 26 | 22 | - | 4.73 | 8.71 | |||

| 55/15 | 27 | 24 | - | 4.59 | 9.21 | |||

| 55/15 | 28 | 26 | - | 4.44 | 9.64 | |||

| 55/15 | 29 | 28 | - | 4.29 | 10.04 | |||

| 55/15 | 30 | 30 | - | 4.15 | 10.40 | |||

| 55/15 | 31 | 2600 | 18 | 50.0 | - | 5.04 | 7.94 | |

| 55/15 | 32 | 20 | - | 4.82 | 8.42 | |||

| 55/15 | 33 | 22 | - | 4.64 | 8.91 | |||

| 55/15 | 34 | 24 | - | 4.48 | 9.38 | |||

| 55/15 | 35 | 26 | - | 4.33 | 9.81 | |||

| 55/15 | 36 | 28 | - | 4.19 | 10.21 | |||

| 55/15 | 37 | 30 | - | 4.06 | 10.59 | |||

| 55/15 | 38 | 2800 | 18 | 50.0 | - | 4.88 | 8.30 | |

| 55/15 | 39 | 20 | - | 4.64 | 8.78 | |||

| 55/15 | 40 | 22 | - | 4.47 | 9.28 | |||

| 55/15 | 41 | 24 | - | 4.30 | 9.75 | |||

| 55/15 | 42 | 26 | - | 4.15 | 10.17 | |||

| 55/15 | 43 | 28 | - | 4.01 | 10.58 | |||

| 55/15 | 44 | 30 | - | 3.87 | 10.95 | |||

| 55/15 | 45 | 3000 | 18 | 50.0 | - | 4.68 | 8.58 | |

| 55/15 | 46 | 20 | - | 4.47 | 9.10 | |||

| 55/15 | 47 | 22 | - | 4.30 | 9.61 | |||

| 55/15 | 48 | 24 | - | 4.13 | 10.06 | |||

| 55/15 | 49 | 26 | - | 3.99 | 10.52 | |||

| 55/15 | 50 | 28 | - | 3.85 | 10.93 | |||

| 55/15 | 51 | 30 | - | 3.71 | 11.29 | |||

| 55/15 | 52 | 35.0 | 48.80 | - | 3.02 | |||

| 55/15 | 53 | 1000 | 11 | 42.5 | 48.78 | - | 3.03 | |

| 55/15 | 54 | 50.0 | 48.74 | - | 3.05 | |||

| 55/15 | 55 | 35.0 | 42.77 | - | 5.96 | |||

| 55/15 | 56 | 1000 | 23 | 42.5 | 42.72 | - | 5.99 | |

| 55/15 | 57 | 50.0 | 42.61 | - | 6.05 | |||

| 55/15 | 58 | 35.0 | 37.22 | - | 8.67 | |||

| 55/15 | 59 | 1000 | 35 | 42.5 | 37.14 | - | 8.71 | |

| 55/15 | 60 | 50.0 | 36.94 | - | 8.81 | |||

| 55/15 | 61 | 35.0 | 46.56 | - | 4.11 | |||

| 55/15 | 62 | 2000 | 11 | 42.5 | 46.52 | - | 4.14 | |

| 55/15 | 63 | 50.0 | 46.39 | - | 4.20 | |||

| 55/15 | 64 | 35.0 | 38.96 | - | 7.82 | |||

| 55/15 | 65 | 2000 | 23 | 42.5 | 38.87 | - | 7.86 | |

| 55/15 | 66 | 50.0 | 38.63 | - | 7.98 | |||

| 55/15 | 67 | 35.0 | 32.70 | - | 10.87 | |||

| 55/15 | 68 | 2000 | 35 | 42.5 | 32.53 | - | 10.95 | |

| 55/15 | 69 | 50.0 | 32.17 | - | 11.12 | |||

| 55/15 | 70 | 35.0 | 43.47 | - | 5.62 | |||

| 55/15 | 71 | 3000 | 11 | 42.5 | 43.37 | - | 5.67 | |

| 55/15 | 72 | 50.0 | 43.18 | - | 5.76 | |||

| 55/15 | 73 | 3000 | 23 | 35.0 | 35.64 | - | 9.43 | |

| 55/15 | 74 | 42.5 | 35.31 | - | 9.60 | |||

| 55/15 | 75 | 3000 | 50.0 | 34.89 | - | 9.81 | ||

| 55/15 | 76 | 35.0 | 29.19 | - | 12.59 | |||

| 55/15 | 77 | 3000 | 35 | 42.5 | 28.75 | - | 12.80 | |

| 55/15 | 78 | 50.0 | 28.16 | - | 13.08 | |||

| [83] | 65/30 | 79 | 2000 | 16 | 50.0 | - | - | 2.73 |

| 65/30 | 80 | 2200 | - | - | 2.95 | |||

| 65/30 | 81 | 2400 | - | - | 3.19 | |||

| 65/30 | 82 | 2500 | - | - | 3.31 | |||

| 65/30 | 83 | 2600 | - | - | 3.42 | |||

| 65/30 | 84 | 2800 | - | - | 3.65 | |||

| 65/30 | 85 | 3000 | - | - | 3.88 | |||

| 65/30 | 86 | 2000 | 18 | 50.0 | - | - | 3.07 | |

| 65/30 | 87 | 2200 | - | - | 3.32 | |||

| 65/30 | 88 | 2400 | - | - | 3.59 | |||

| 65/30 | 89 | 2500 | - | - | 3.72 | |||

| 65/30 | 90 | 2600 | - | - | 3.85 | |||

| 65/30 | 91 | 2800 | - | - | 4.10 | |||

| 65/30 | 92 | 3000 | - | - | 4.36 | |||

| 65/30 | 93 | 2000 | 20 | 50.0 | - | - | 3.42 | |

| 65/30 | 94 | 2200 | - | - | 3.69 | |||

| 65/30 | 95 | 2400 | - | - | 3.99 | |||

| 65/30 | 96 | 2500 | - | - | 4.13 | |||

| 65/30 | 97 | 2600 | - | - | 4.27 | |||

| 65/30 | 98 | 2800 | - | - | 4.56 | |||

| 65/30 | 99 | 3000 | - | - | 4.85 | |||

| 65/30 | 100 | 2000 | 22 | 50.0 | - | - | 3.76 | |

| 65/30 | 101 | 2200 | - | - | 4.06 | |||

| 65/30 | 102 | 2400 | - | - | 4.39 | |||

| 65/30 | 103 | 2500 | - | - | 4.55 | |||

| 65/30 | 104 | 2600 | - | - | 4.70 | |||

| 65/30 | 105 | 2800 | - | - | 5.02 | |||

| 65/30 | 106 | 3000 | - | - | 5.33 | |||

| 65/30 | 107 | 2000 | 24 | 50.0 | - | - | 4.10 | |

| 65/30 | 108 | 2200 | - | - | 4.43 | |||

| 65/30 | 109 | 2400 | - | - | 4.78 | |||

| 65/30 | 110 | 2500 | - | - | 4.96 | |||

| 65/30 | 111 | 2600 | - | - | 5.13 | |||

| 65/30 | 112 | 2800 | - | - | 5.47 | |||

| 65/30 | 113 | 3000 | - | - | 5.82 | |||

| 65/30 | 114 | 2000 | 26 | 50.0 | - | - | 4.44 | |

| 65/30 | 115 | 2200 | - | - | 4.80 | |||

| 65/30 | 116 | 2400 | - | - | 5.20 | |||

| 65/30 | 117 | 2500 | - | - | 5.40 | |||

| 65/30 | 118 | 2600 | - | - | 5.56 | |||

| 65/30 | 119 | 2800 | - | - | 5.93 | |||

| 65/30 | 120 | 3000 | - | - | 6.30 | |||

| 65/30 | 121 | 2000 | 28 | 50.0 | - | - | 4.78 | |

| 65/30 | 122 | 2200 | - | - | 5.17 | |||

| 65/30 | 123 | 2400 | - | - | 5.58 | |||

| 65/30 | 124 | 2500 | - | - | 5.79 | |||

| 65/30 | 125 | 2600 | - | - | 5.98 | |||

| 65/30 | 126 | 2800 | - | - | 6.38 | |||

| 65/30 | 127 | 3000 | - | - | 6.79 | |||

| 65/30 | 128 | 2000 | 30 | 50.0 | - | - | 5.12 | |

| 65/30 | 129 | 2200 | - | - | 5.53 | |||

| 65/30 | 130 | 2400 | - | - | 5.98 | |||

| 65/30 | 131 | 2500 | - | - | 6.20 | |||

| 65/30 | 132 | 2600 | - | - | 6.41 | |||

| 65/30 | 133 | 2800 | - | - | 6.84 | |||

| 65/30 | 134 | 3000 | - | - | 7.27 |

| N | Correlation | L (mm) | Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | Qt = 1.520 L | 2200 | Qt = 170.75N |

| 20 | Qt = 1.6749 L | 2400 | Qt = 184.57N |

| 22 | Qt = 1.8244 L | 2500 | Qt = 199.33N |

| 24 | Qt = 1.9816 L | 2600 | Qt = 206.62N |

| 26 | Qt = 2.1371 L | 2800 | Qt = 213.67N |

| 28 | Qt = 2.2911 L | 3000 | Qt = 228.01N |

| 30 | Qt = 2.4426 L | 2000 | Qt = 242.39N |

| Authors | Representation | Radiator Block | Load | Tamb [°C] | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

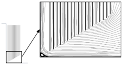

| [87] |  | L = 1500 mm; W = 520 mm; N = 38; e = 8 mm | 3400 kVA | 25 | 50% land mass reduction; 15% efficiency increase |

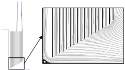

| [88] |  | - | 150 MVA | - | 38% area reduction in radiator; 40% oil flow rate increase |

| Author | Scheme | Fans | Radiator Block | Oil Flow Rate [m3/s] | Cooling Power [kW] | Heat Transfer Coefficient [W/m2·K] | Factor of Merit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [101] |  | = 33.7 °C; 2 fans; 4 blades/fan; 550 RPM | = 55.8 °C; Nr = 5 radiators; L = 2000 mm; D = 50 mm; N = 27 | 0.294 kg/s | 46.24 | - | - |

| = 33.7 °C; 2 fans; 4 blades/fan; 550 RPM | = 55.8 °C; Nr = 5 radiators; L = 2000 mm; D = 50 mm; N = 27 | - | 43.58 | - | - | |

| [80] |  | = 50 °C; 3 fans; Diameter: 500 mm; 7 blades; 940 RPM; with casing | = 93 °C; Nr = 4 radiators; L = 2600 mm; D = 50 mm; N = 14 | - | 67.5 | 14.4 | - |

| = 50 °C; 3 fans; Diameter 500 mm; 7 blades; 1130 RPM; with casing | = 93 °C; Nr = 4 radiators; L = 2600 mm; D = 50 mm; N = 14 | - | 78 | 16.5 | - | |

| = 50 °C; 3 fans; Diameter 610 mm; 4 blades; 700 RPM; no casing | = 93 °C; Nr = 4 radiators; L = 2600 mm; D = 50 mm; N = 14 | - | 61 | 13.4 | - | |

| = 50 °C; Diameter: 610 mm; 3 fans; 4 blades; 900 RPM; no casing | = 93 °C; Nr = 4 radiators; L = 2600 mm; D = 50 mm; N = 14 | - | 75 | 16 | - | |

| = 50 °C; 3 fans; Diameter: 500 mm; 7 blades; 940 RPM; with casing | = 93 °C; N = 4 radiators; L = 2600 mm; D = 50 mm; N = 14 | - | 73 | 15.1 | 55.2 | |

| = 50 °C; 3 fans; Diameter 500 mm; 7 blades; 1130 RPM; with casing | = 93 °C; Nr = 4 radiators; L = 2600 mm; D = 50 mm; N = 14 | - | 84.5 | 14 | 39.8 | |

| = 50 °C; 3 fans; Diameter 610 mm; 4 blades; 700 RPM; no casing | = 93 °C; Nr = 4 radiators; L = 2600 mm; D = 50 mm; N = 14 | - | 65 | 17.4 | 66.5 | |

| = 50 °C; Diameter: 610 mm; 3 fans; 4 blades; 900 RPM; no casing | = 93 °C; Nr = 4 radiators; L = 2600 mm; D = 50 mm; N = 14 | - | 80 | 16.8 | 40 | |

| = 50 °C; Diameter: 610 mm; 2 fans; 4 blades; 900 RPM; no casing | = 93 °C; Nr = 4 radiators; L = 2600 mm; D = 50 mm; N = 14 | - | 65.4 | - | 46 | |

| = 50 °C; Diameter 610 mm; 3 fans; 4 blades; 900 RPM; no casing; Offset = 50 mm | = 93 °C; N = 4 radiators; L = 2600 mm; D = 50 mm; N = 14 | - | 82.4 | - | 40.6 | |

| [102] |  | Diameter 1000 mm; 2 fans; 7 blades; 860 RPM; no casing | = 33.7 °C; Nr = 4 radiators; L = 3000 mm; D = 50 mm; N = 30 | - | 65.5 | 17.8 | - |

| Diameter 1000 mm; 2 fans; 7 blades; 860 RPM; no casing | = 33.7 °C; Nr = 4 radiators; L = 3000 mm; D = 50 mm; N = 30 | - | 65 | 17.5 | - | |

| [71] |  | = 20 °C; Diameter 600 mm; 6 fans; 4 blades; 550 RPM; Power consumption unit: 122.58 W | = 75 °C; Nr = 5 radiators; L = 2500 mm; D = 60 mm; N = 30 | 0.00074 0.00221 0.00369 0.00516 | 209.9 299.87 320.85 329.79 | 10.17 14.59 15.61 16.05 | 269.6/60.5 * 482.5/133.8 * 544.2/153.5 * 564.5/162.6 * |

| = 20 °C; Diameter 600 mm; 6 fans; 4 blades; 550 RPM; With casing; Power consumption unit: 122.58 W | = 75 °C; Nr = 5 radiators; L = 2500 mm; D = 60 mm; N = 30 | 0.00074 0.00221 0.00369 0.00516 | 223.06 324.19 349.82 361.22 | 10.85 15.77 17.02 17.58 | 308.3/73.6 * 550.7/158.2 * 616.13/182.5 * 646.5/194.0 * |

| Author | Scheme | Fans | Radiator Block | Oil Flow Rate [m3/s] | Cooling Power [kW] | Heat Transfer Coefficient [W/m2·K] | Factor of Merit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [102] |  | = 39.8 °C; Diameter 1000 mm; 2 fans; 7 blades; 860 RPM; no casing | = 56.1 C; Nr = 4 radiators; L = 3000 mm; D = 50 mm; N = 30 | - | 63 | 16.8 | - |

| - | 59.5 | 16 | - | |||

| [2] |  | = 20 °C; Diameter 600 mm; 2 fans; 4 blades; 550 RPM; With casing; Power consumption unit: 122.58 W | = 75 °C; Nr = 5 radiators; L = 2348 mm; D = 35 mm; N = 30 | 0.00074 0.00221 0.00369 0.00516 | 165.27 216.22 225.44 228.68 | 8.11 10.52 10.97 11.13 | 674.13 881.96 919.56 932.78 |

| 0.00074 0.00221 0.00369 0.00516 | 189.32 250.20 261.60 265.10 | 9.21 12.17 12.73 12.92 | 772.23 1020.56 1067.06 1082.34 | |||

| 0.00074 0.00221 0.00369 0.00516 | 195.76 257.73 269.77 273.55 | 9.49 12.53 13.12 13.40 | 798.50 1051.27 1110.38 1115.80 | |||

| 0.00074 0.00221 0.00369 0.00516 | 183.26 242.52 254.91 258.85 | 8.92 11.80 12.40 12.59 | 747.51 989.23 1039.77 1055.84 | |||

| 0.00074 0.00221 0.00369 0.00516 | 194.10 259.60 273.53 278.07 | 9.48 12.63 13.31 13.53 | 791.73 1058.90 1115.72 1134.24 | |||

| 0.00074 0.00221 0.00369 0.00516 | 201.29 263.73 278.81 279.64 | 9.79 12.83 13.57 13.65 | 821.06 1075.75 1137.26 1140.64 | |||

| 0.00074 0.00221 0.00369 0.00516 | 164.64 222.04 234.38 238.69 | 8.01 10.80 11.40 11.61 | 671.56 905.69 956.03 973.61 | |||

| 0.00074 0.00221 0.00369 0.00516 | 181.36 243.52 259.06 263.46 | 8.82 11.85 12.60 12.82 | 739.76 993.31 1056.70 1074.65 | |||

| 0.00074 0.00221 0.00369 0.00516 | 190.16 253.26 267.50 271.79 | 9.25 12.32 13.02 13.22 | 775.66 1033.04 1091.12 1108.62 |

| Scheme | Fans | Radiator Block | Cooling Power [kW] |

| = 50 °C; Diameter 500 mm; 3 fans; = 7 m/s. | Nr = 4 radiators; L = 2600 mm; N = 14. | 39.4 |

| 40.2 | ||

| 36.7 | ||

| 40.7 |

| Author | Enhancement Representation | Radiator Block | Enhancements | [°C] | Toil [°C] | Impact on Power Cooling [kW] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [20] |  | L = 1200 mm; W = 520 mm; N = 14; e = 6 mm | ChimneyWind Deflector | 25 | - | (+14.76%) |

| [81] |  | L = 1200 mm; W = 520 mm; N = 14; e = 6 mm; d = 45 mm | ChimneyWind Deflector | 24.85 | 69.9 | (+26.54%) |

| [82] |  | L = 1800 mm; W = 500 mm; N = 26; e = 8 mm | Turbulators used in the middle of the oil channel | 29.85 | 69.85 | - |

| [82] |  | L = 1800 mm; W = 500 mm; N = 26; e = 8 mm | Wall indentators | 29.85 | 69.85 | (+36%) |

| [18] |  | L = 2400 mm; W = 979 mm; N = 18; e = 11.9 mm | Trapezoidal radiator + panel area expansion | 25.5 | 69.89 | 12.9 (+16.9%) |

| [18] |  | L = 2400 mm; W = 979 mm; N = 18; e = 11.9 mm | Trapezoidal radiator | 25.5 | 69.89 | 12.2 (+10.2%) |

| [18] |  | L = 2400 mm; W = 979 mm; N = 18; e = 11.9 mm | ChimneyTrapezoidal radiator + panel area expansion | 25.5 | 69.89 | 15.4 (+39.5%) |

| [13] |  | - | Water film on the outer wall of the heat exchanger | 25 | - | - |

| Author | Radiator Block | Heat Transfer Coefficient and Nusselt Number |

|---|---|---|

| [19] | Convective; Oil | |

| [91] | Convective; Oil | |

| [77] | Convective; Oil; End-fins | |

| [77] | Convective; Oil; Inner-fins | , for S/L = 0 |

| [90] | Convective; Overall | |

| [91] | Convective; Air | |

| [91] | Conduction; Steel | |

| [19] | Radiation | |

| [91] | Overall |

| Author | Category | Inputs | Fluid Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| [84] | Oil | °C °C N.S. | - |

| [78] | Oil | = 20 °C; = 75 °C ; ; | |

| [90] | Oil | = 22 °C; = 62 °C ; ; ; | - |

| Author | Flow Rate (m3/s) | Temperature Prediction (°C) | Heat Dissipation (W) |

|---|---|---|---|

| [84] | - | ||

| [78] | On individual fins Overall | ||

| [90] | - |

| Article | Simulation Considerations | Av. Error Compared with Experimental: Cooling Power (%) | Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| [71] | Turbulence model: standard ; Velocity-pressure coupling (SIMPLE); Natural convection: Boussinesq approximation; Conjugation of heat transfer and fluid flow in the geometry of radiators: PMA (Porous Media Approach); Software: ANSYS FLUENT 13.0 | 5.15% | Compare Horizontal and Vertical ventilation |

| [102] | Turbulence model: Shear Stress Transport (SST); Eddy viscosity; Radiation: Calculated by DTM - Discrete Transfer Model; Software: Ansys CFXV. 12.1 | No experimentally validated | Compare four different cooling fan configurations |

| [2] | Turbulence model: standard ; Velocity-pressure coupling (SIMPLE); Natural convection: Boussinesq approximation; Conjugation of heat transfer and fluid flow in the geometry of radiators: PMA (Porous Media Approach); Software: ANSYS FLUENT 13.0 | 5.15% | Compare nine different cooling fan configurations |

| [80] | Turbulence model: Shear Stress Transport (SST); Software: Commercial flow solver (not specified) | 6.05% | Compare Horizontal and Vertical ventilation and uncentered fans |

| [90] | Radiation: Not considered; Software: ANSYS product (not specified) | No experimentally validated | Investigating temperature rise characteristics of radiators |

| [18] | Turbulence model: Shear Stress Transport (SST); Radiation: Calculated by DTM; Software: Ansys Fluent 18.0 | No experimentally validated | Study new radiator design options |

| [101] | Turbulence model: Shear Stress Transport (SST); Radiation: Calculated by DTM; Software: Ansys CFX 12.1 | 17.35% | Compare Horizontal and Vertical ventilation |

| [79] | Turbulence model: Germano’s model [111] (LES); Velocity-pressure coupling (SIMPLEC); Software: HPC CFD Code Saturne | Validated but do not compare the values with experimental data | Reduced model validation |

| [1] | Turbulence model: k-w SST; Pressure discretisation (PRESTO); Software: Ansys Fluent 2023 R1©; Radiation: Surface to Surface (S2S)—Ray Tracing | 7.90% | Parametric study and optimization design of radiators (Oil and air simulation) |

| [83] | Turbulence model: k-w SST; Pressure discretisation (PRESTO); Software: Ansys Fluent 2023 R1©; Radiation: Surface to Surface (S2S)—Ray Tracing | 9.80% | Parametric study and optimization design of radiators to train artificial neural networks to cooling power estimation |

| [91] | Turbulence model: LES; Velocity-pressure coupling (SIMPLEC); | 30.00 % | Analyse the cooling capacity, validate the numerical simulation and calculation procedures for further design on a radiator with ONAN mode |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sorte, S.; Monteiro, A.F.; Ventura, D.; Salgado, A.; Oliveira, M.S.A.; Martins, N. Power Transformers Cooling Design: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2025, 18, 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051051

Sorte S, Monteiro AF, Ventura D, Salgado A, Oliveira MSA, Martins N. Power Transformers Cooling Design: A Comprehensive Review. Energies. 2025; 18(5):1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051051

Chicago/Turabian StyleSorte, Sandra, André Ferreira Monteiro, Diogo Ventura, Alexandre Salgado, Mónica S. A. Oliveira, and Nelson Martins. 2025. "Power Transformers Cooling Design: A Comprehensive Review" Energies 18, no. 5: 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051051

APA StyleSorte, S., Monteiro, A. F., Ventura, D., Salgado, A., Oliveira, M. S. A., & Martins, N. (2025). Power Transformers Cooling Design: A Comprehensive Review. Energies, 18(5), 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051051