Valorization of Forest Biomass Through Pyrolysis: A Study on the Energy Potential of Wood Tars

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Raw Material—Wood

2.1.2. Material Used in the Tests—Wood Tar

2.2. Methods

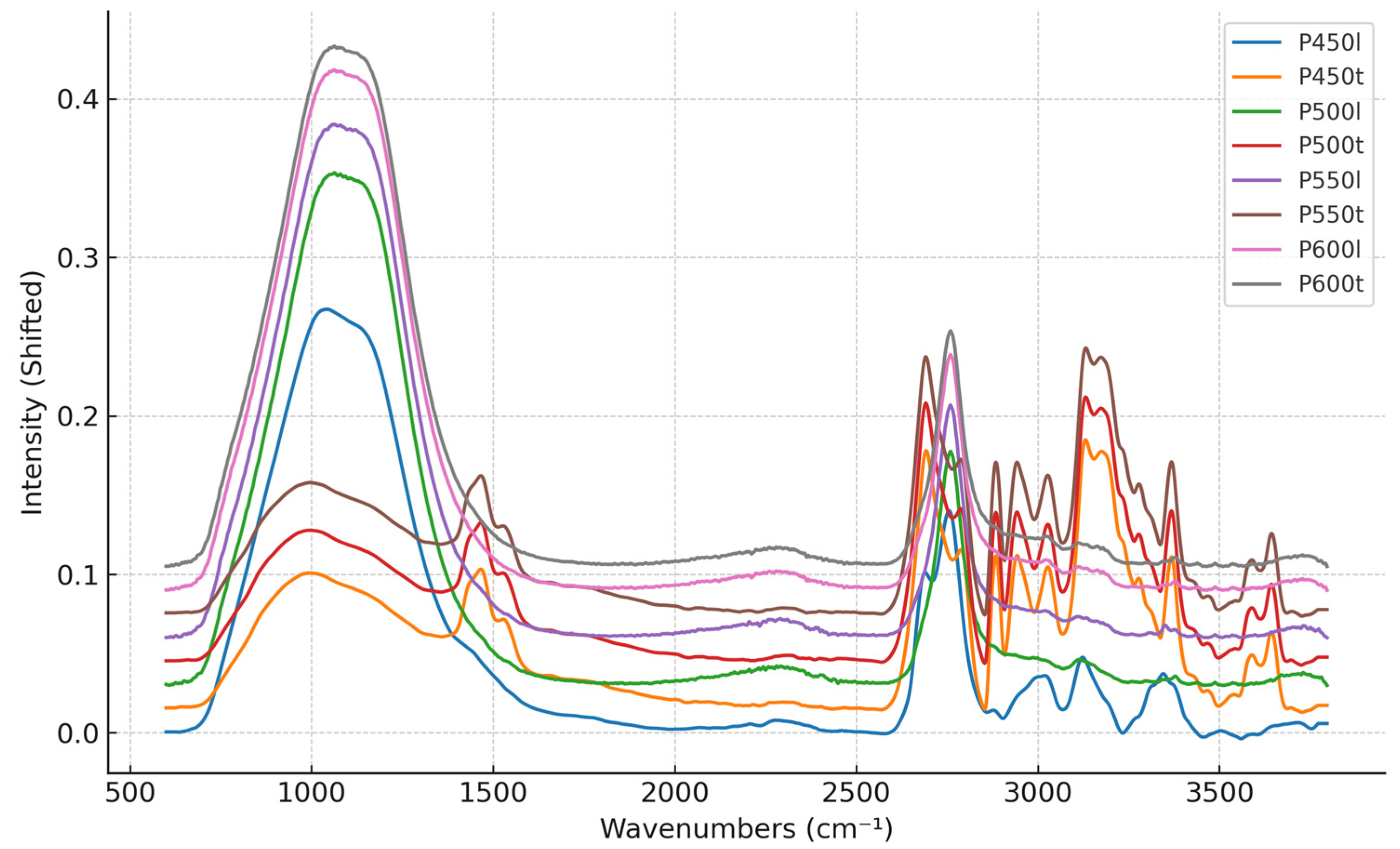

2.2.1. FTIR Analysis

- -

- Wavenumber range: 3700 cm−1–700 cm−1—covers the vibrational regions of key functional groups.

- -

- Resolution: 4 cm−1—provides sufficient spectral resolution for detailed peak analysis.

- -

- Background correction: performed before each measurement to eliminate environmental interference (e.g., water vapor and carbon dioxide absorption).

- -

- Spectral normalization to eliminate differences in sample thickness.

- -

- Baseline correction to minimize background interference from atmospheric absorption.

- -

- Smoothing algorithms to reduce noise and enhance peak clarity.

- -

- Differential analysis to highlight spectral differences between samples.

2.2.2. Moisture Content, Elemental Composition, and Ash Content

2.2.3. Calorific Value

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results of FTIR Analysis

3.2. Elemental Composition

3.3. Moisture Content, Ash Content, and Thermal Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mignogna, D.; Szabó, M.; Ceci, P.; Avino, P. Biomass Energy and Biofuels: Perspective, Potentials, and Challenges in the Energy Transition. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odzijewicz, J.I.; Wołejko, E.; Wydro, U.; Wasil, M.; Jabłońska-Trypuć, A. Utilization of Ashes from Biomass Combustion. Energies 2022, 15, 9653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Bioenergy Statistics 2022; World Bioenergy Association: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022.

- Kilpeläinen, A.; Peltola, H. Carbon Sequestration and Storage in European Forests. In Forest Bioeconomy and Climate Change; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F.; Dawood, A.; Hussain, A.; Alnasir, M.H.; Khan, M.A.; Butt, T.M.; Janjua, N.K.; Hamid, A. Fueling the Future: Biomass Applications for Green and Sustainable Energy. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighalo, J.O.; Iwuchukwu, F.U.; Eyankware, O.E.; Iwuozor, K.O.; Olotu, K.; Bright, O.C.; Igwegbe, C.A. Flash Pyrolysis of Biomass: A Review of Recent Advances. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2022, 24, 2349–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richert, A.; Malinowski, R.; Ringwelska, M.; Dąbrowska, G.B. Birch Tar Introduced into Polylactide and Its Influence on the Barrier, Thermal, Functional and Biological Properties of the Film Obtained by Industrial Extrusion. Materials 2022, 15, 7382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richert, A.; Kalwasińska, A.; Brzezinska, M.S.; Dąbrowska, G.B. Biodegradability of Novel Polylactide and Polycaprolactone Materials with Bacteriostatic Properties Due to Embedded Birch Tar in Different Environments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richert, A.; Olewnik-Kruszkowska, E.; Dąbrowska, G.B.; Dąbrowski, H.P. The Role of Birch Tar in Changing the Physicochemical and Biocidal Properties of Polylactide-Based Films. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dąbrowska, G.B.; Szydłowska-Czerniak, A.; Raszkowska-Kaczor, A.; Antoszewski, M.; Jędrzejewski, T.; Dąbrowski, H.P.; Bartkowiak, M.; Katolik, Z.; Brózdowski, J.; Cofta, G.; et al. The Physicochemical, Biocidal, and Antioxidant Properties of Carboxymethylcellulose-Based Films with Liquid Pyrolysis Products of Wood Pine. In Proceedings of the 4th Edition of International Conference “Plant Productivity and Food Safety: Microbiology, Soil Science, Food Quality and Agricultural Genetics”, Toruń, Poland, 26 September 2024; p. 118. [Google Scholar]

- Dąbrowska, G.; Garstecka, Z.; Narbutt, O.; Dąbrowski, H.P.; Pyrkosz, W. Trichoderma Harzianum ZggD-19 Fungus Strain, Method for Biostimulation of the Growth of Rapeseed and Crop Plants from the Brassicaceae Family, Method for Protecting Rapeseed and Crop Plants from the Brassicaceae Family and Solution for Protecting Rapeseed and Crop Plants from the Brassicaceae Family. PL Patent Pat.239,212, 1 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zborowska, M.; Brózdowski, J.; Starlander, J.; Woitsch, J.; Ribechini, E.; Ion, R.-M.; Nelle, O.; Deforce, K.; Varga, A.; Szabó, P. Network for Forest By-Products Charcoal, Resin, Tar, Potash (COST Action EU-PoTaRCh). Open Res. Eur. 2024, 4, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.; Park, Y.-K.; Kwon, E.E. Strategic Use of Biochar for CO2 Capture and Sequestration. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 32, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, M.E.A.; Pasa, V.M.D.; Lessa, A. Continuous Charcoal Production—A Brazilian Experience. In Advances in Thermochemical Biomass Conversion; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 1994; pp. 1289–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Fagernäs, L.; Kuoppala, E.; Tiilikkala, K.; Oasmaa, A. Chemical Composition of Birch Wood Slow Pyrolysis Products. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, I.A. Detection of the Methoxyl Group by Infrared Spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 1968, 22, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, R.M.; Bassler, G.C.; Morrill, T.C. Characteristic Group Absorptions of Organic Molecules. In Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds, 5th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1991; Volume 103. [Google Scholar]

- Ribechini, E.; Orsini, S.; Silvano, F.; Colombini, M.P. Py-GC/MS, GC/MS and FTIR Investigations on LATE Roman-Egyptian Adhesives from Opus Sectile: New Insights into Ancient Recipes and Technologies. Anal. Chim. Acta 2009, 638, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcañiz-Monge, J.; Cazorla-Amorós, D.; Linares-Solano, A. Characterisation of Coal Tar Pitches by Thermal Analysis, Infrared Spectroscopy and Solvent Fractionation. Fuel 2001, 80, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. 16948: 2015-07; Solid Biofuels—Determination of Total Carbon, Hydrogen and Nitrogen Content. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- P. 18122: 2016-01; English Version—Solid Biofuels—Determination of Ash Content. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- E.N. 18125: 2017; Solid Biofuels. Determination of Calorific Value. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2017.

- P. 16994: 2016-10; Biopaliwa Stałe–Oznaczanie Całkowitej Zawartości Siarki i Chloru [Solid Biofuels—Determination of Total Content of Sulfur and Chlorine]. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny: Warsaw, Poland, 2016.

- Jin, H.; Yuan, W.; Li, W.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Qi, F. Combustion Chemistry of Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2023, 96, 101076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Quinton, K.S.; Peng, Z.; Zhao, H.; Ladommatos, N. Effects of Oxygen Content of Fuels on Combustion and Emissions of Diesel Engines. Energies 2016, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefort, B.; Tsang, W. High Temperature Stability of Larger Aromatic Compounds. Combust. Flame 2011, 158, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trubetskaya, A.; Von Berg, L.; Johnson, R.; Moore, S.; Leahy, J.J.; Han, Y.; Lange, H.; Anca-Couce, A. Production and Characterization of Bio-Oil from Fluidized Bed Pyrolysis of Olive Stones, Pinewood, and Torrefied Feedstock. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2023, 169, 105841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Lu, J.; Yang, M.; Wu, Y. Improved Bio-Oil Quality from Pyrolysis of Pine Biomass in Pressurized Hydrogen. Appl. Sci. 2021, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negahdar, L.; Gonzalez-Quiroga, A.; Otyuskaya, D.; Toraman, H.E.; Liu, L.; Jastrzebski, J.T.B.H.; Van Geem, K.M.; Marin, G.B.; Thybaut, J.W.; Weckhuysen, B.M. Characterization and Comparison of Fast Pyrolysis Bio-Oils from Pinewood, Rapeseed Cake, and Wheat Straw Using 13C NMR and Comprehensive GC × GC. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 4974–4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Ichsan, G.M.H.; Nugrahaningtiyas, K.D.; Widjonarko, D.M.; Rahmawati, F.; Lestari, W.W. Conversion of Wood Waste to Be a Source of Alternative Liquid Fuel Using Low Temperature Pyrolysis Method. J. Kim. Sains Apl. 2019, 22, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.K.; Kyin, E.H.; Hua, L.S.; Chen, L.W.; Yee, C.Y. Yield and Calorific Value of Bio Oil Pyrolysed from Oil Palm Biomass and Its Relation with Solid Residence Time and Process Temperature. Asian J. Sci. Res. 2015, 8, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abnisa, F.; Arami-Niya, A.; Daud, W.M.A.W.; Sahu, J.N. Characterization of Bio-Oil and Bio-Char from Pyrolysis of Palm Oil Wastes. Bioenergy Res. 2013, 6, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Ganesh, A. Bio-Oil from Pyrolysis of Cashew Nut Shell—A near Fuel. Biomass Bioenergy 2003, 25, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujahid, R.; Riaz, A.; Insyani, R.; Kim, J. A Centrifugation-First Approach for Recovering High-Yield Bio-Oil with High Calorific Values in Biomass Liquefaction: A Case Study of Sewage Sludge. Fuel 2020, 262, 116628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Sun, S.; Ma, R.; Fang, L.; Zhang, P.; Qu, J.; Zhang, X.; Geng, H.; Huang, X. Characteristics and Reaction Mechanisms of Sludge-Derived Bio-Oil Produced through Microwave Pyrolysis at Different Temperatures. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 160, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveendran, K.; Ganesh, A. Heating Value of Biomass and Biomass Pyrolysis Products. Fuel 1996, 75, 1715–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pyrolysis Efficiency [%] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pine Product | Birch Product | |||||||

| P450 | P500 | P550 | P600 | B450 | B500 | B550 | B600 | |

| Liquid (wood tar) | 34 | 33 | 56 | 45 | 53 | 54 | 54 | 54 |

| Biochar | 28 | 18 | 22 | 20 | 31 | 28 | 28 | 27 |

| Gases | 38 | 49 | 22 | 35 | 16 | 18 | 18 | 19 |

| Material, Temperature, and Product | Symbol | Material, Temperature, and Product | Symbol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pine wood 450 °C, tar | P450t | Birch wood 450 °C, tar | B450t |

| Pine wood 450 °C, liquid | P450l | Birch wood 450 °C, liquid | B450l |

| Pine wood 500 °C, tar | P500t | Birch wood 500 °C, tar | B500t |

| Pine wood 500 °C, liquid | P500l | Birch wood 500 °C, liquid | B500l |

| Pine wood 550 °C, tar | P550t | Birch wood 550 °C, tar | B550t |

| Pine wood 550 °C, liquid | P550l | Birch wood 550 °C, liquid | B550l |

| Pine wood 600 °C, tar | P600t | Birch wood 600 °C, tar | B600t |

| Pine wood 600 °C, liquid | P600l | Birch wood 600 °C, liquid | B600l |

| Element [%] | B450l | B450t | B500l | B500t | B550l | B550t | B600l | B600t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen | 6.7 ± 0.3 | 7.3 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 0.1 | 7.3 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 0.1 | 7.2 ± 0.1 | 6.6 ± 0.1 | 7.2 ± 0.1 |

| Carbon | 62.9 ± 0.3 | 69.3 ± 0.2 | 57.0 ± 0.3 | 68.7 ± 0.2 | 58.7 ± 0.6 | 68.5 ± 4.3 | 65.1 ± 0.33 | 68.4 ± 0.4 |

| Nitrogen | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.27 ± 0.05 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.27 ± 0.07 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | 0.20 ± 0.03 |

| Sulfur | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| Element [%] | P450l | P450t | P500l | P500t | P550l | P550t | P600l | P600t |

| Hydrogen | 6.7 ± 0.2 | 7.3 ± 0.1 | 6.6 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 6.6 ± 0.1 | 7.3 ± 0.1 | 6.7 ± 0.1 | 7.2 ± 0.1 |

| Carbon | 57.7 ± 0.8 | 70.2 ± 0.8 | 59.9 ± 0.5 | 70.0 ± 0.3 | 61.5 ± 0.2 | 70.5 ± 0.3 | 61.8 ± 0.3 | 70.4 ± 0.2 |

| Nitrogen | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.28 ± 0.07 | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | 0.20 ± 0.04 |

| Sulfur | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| Property | B450l | B450t | B500l | B500t | B550l | B550t | B600l | B600t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture content [%] | 87.1 ± 3.2 | 52.5 ± 2.3 | 82.2 ± 3.0 | 53.8 ± 3.5 | 82.2 ± 3.0 | 53.9 ± 3.1 | 72.1 ± 5.1 | 49.6 ± 2.4 |

| Ash [%] | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Gross calorific value [MJ/kg] | 36.4 ± 2.8 | 45.2 ± 0.7 | 29.3 ± 3.0 | 47.2 ± 2.2 | 39.4 ± 5.8 | 44.0 ± 0.8 | 32.3 ± 1.6 | 41.7 ± 2.4 |

| Net calorific value [MJ/kg] [kWh/kg] | 2.4 ± 1.2 0.7 ± 0.3 | 19.4 ± 1.1 5.4 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 1.0 0.8 ± 0.3 | 19.7 ± 1.9 5.5 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 1.6 1.3 ± 0.4 | 18.2 ± 1.4 5.1 ± 0.4 | 6.8 ± 3.4 1.9 ± 0.9 | 19.1 ± 1.6 5.3 ± 0.4 |

| Property | P450l | P450t | P500l | P500t | P550l | P550t | P600l | P600t |

| Moisture content [%] | 64.8 ± 4.1 | 42.7 ± 1.6 | 60.5 ± 5.5 | 45.17 ± 1.70 | 63.0 ± 8.3 | 49.0 ± 1.9 | 59.7 ± 16.3 | 47.1 ± 1.8 |

| Ash [%] | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Gross calorific value [MJ/kg] | 30.1 ± 1.1 | 49.5 ± 1.8 | 31.7 ± 1.3 | 47.9 ± 1.2 | 29.8 ± 2.7 | 48.3 ± 4.8 | 30.1 ± 1.6 | 46.5 ± 1.4 |

| Net calorific value [MJ/kg] [kWh/kg] | 8.5 ± 0.9 2.7 ± 0.4 | 26.4 ± 1.3 7.3 ± 0.4 | 10.5 ± 1.6 2.9 ± 0.5 | 24.3 ± 1.0 6.7 ± 0.3 | 8.9 ± 5.2 2.5 ± 0.4 | 22.6 ± 2.6 6.3 ± 0.7 | 10.1 ± 1.2 2.8 ± 0.4 | 22.6 ± 1.1 6.3 ± 0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brózdowski, J.; Witczak, M.; Sikorska, K.; Ratajczak, I.; Woźniak, M.; Bartkowiak, M.; Cofta, G.; Dąbrowska, G.B.; Zborowska, M. Valorization of Forest Biomass Through Pyrolysis: A Study on the Energy Potential of Wood Tars. Energies 2025, 18, 1113. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051113

Brózdowski J, Witczak M, Sikorska K, Ratajczak I, Woźniak M, Bartkowiak M, Cofta G, Dąbrowska GB, Zborowska M. Valorization of Forest Biomass Through Pyrolysis: A Study on the Energy Potential of Wood Tars. Energies. 2025; 18(5):1113. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051113

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrózdowski, Jakub, Magdalena Witczak, Klaudia Sikorska, Izabela Ratajczak, Magdalena Woźniak, Monika Bartkowiak, Grzegorz Cofta, Grażyna B. Dąbrowska, and Magdalena Zborowska. 2025. "Valorization of Forest Biomass Through Pyrolysis: A Study on the Energy Potential of Wood Tars" Energies 18, no. 5: 1113. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051113

APA StyleBrózdowski, J., Witczak, M., Sikorska, K., Ratajczak, I., Woźniak, M., Bartkowiak, M., Cofta, G., Dąbrowska, G. B., & Zborowska, M. (2025). Valorization of Forest Biomass Through Pyrolysis: A Study on the Energy Potential of Wood Tars. Energies, 18(5), 1113. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051113