Mechanical Performance of High-Strength Sustainable Concrete under Fire Incorporating Locally Available Volcanic Ash in Central Harrat Rahat, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

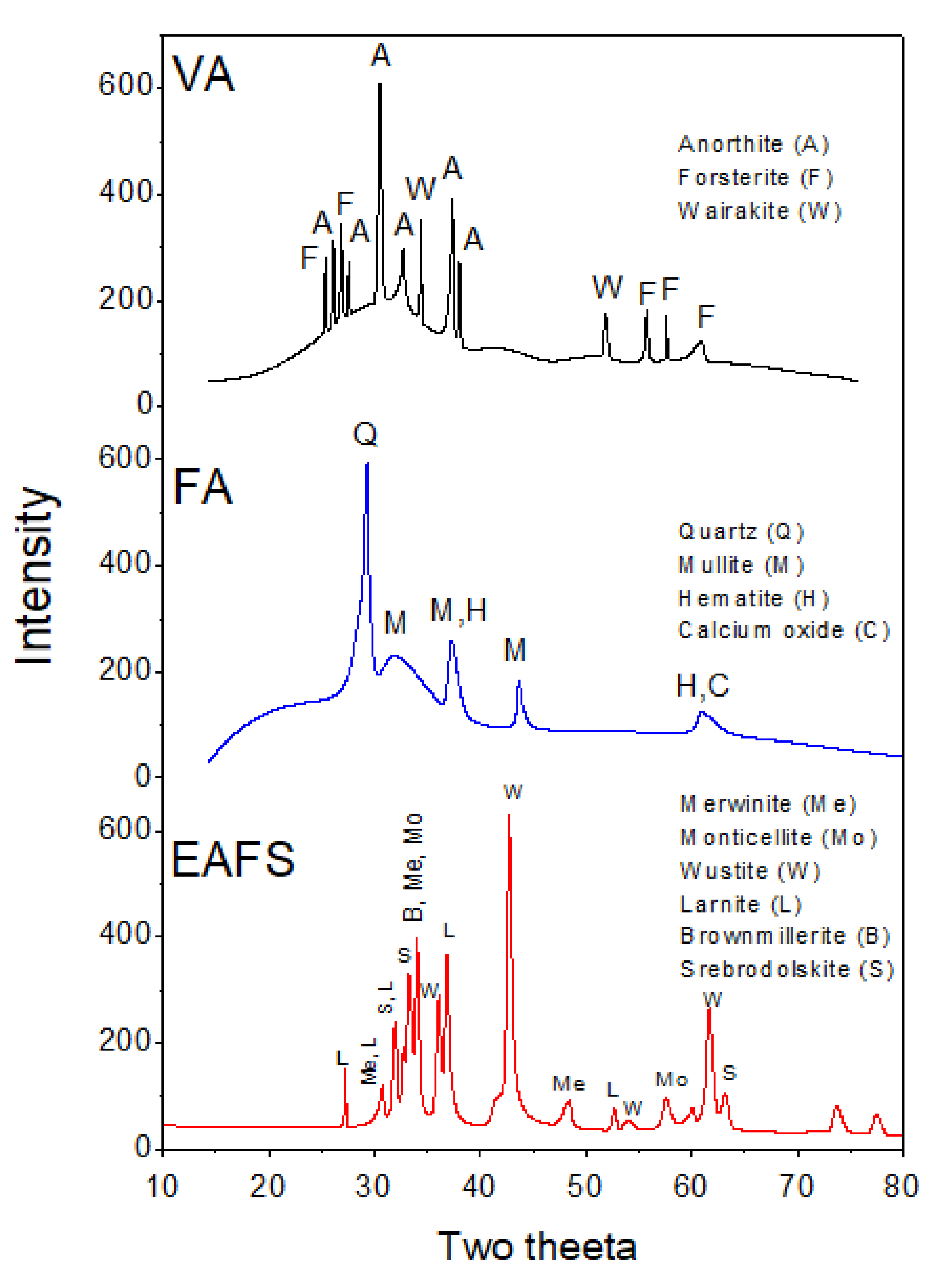

2.1. Materials

Grinding of EAFS

2.2. Mix Proportions and Specimen Preparation

2.2.1. Mix Proportions

2.2.2. Mixing and Preparation of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens

2.3. Test Methods

2.3.1. Thermal Exposure

2.3.2. Weight Loss

2.3.3. Compressive Strength, Splitting Tensile Strength, and Elastic Modulus

2.3.4. Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity

3. Result & Discussion

3.1. Weight Loss

3.2. Mechanical Properties of Concrete before Elevated Temperature Exposure

3.3. Mechanical Properties of Concrete after Elevated Temperature Exposure

3.3.1. Effect of Elevated Temperature on Compressive Strength

3.3.2. Effect of Elevated Temperature on Splitting Tensile Strength

3.3.3. Effect of Elevated Temperature on Elastic Modulus

3.4. Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity Before and After Exposure to Elevated Temperature

3.5. Relationship Between Residual Compressive Strength and UPV

4. Conclusions

- Before exposure to elevated temperatures, HSC incorporating VA (V20 & V20S10) produced either comparable or slightly better results for all mechanical properties (compressive and splitting tensile strengths, elastic modulus, and UPV) to that of reference FA (F20 & F20S10) concrete, irrespective of aging. A slightly lower value of these mechanical properties was observed for the concretes containing pozzolanic materials (VA or FA) when compared to CC, particularly at early ages. This is attributed to the slow pozzolanic reactivity of these pozzolanic materials. However, due to a late pozzolanic reaction with aging, both VA and FA concretes possessed comparable results to that of CC at 91 days.

- Looking at the encouraging response of VA concretes at 91 days, specimens were subjected to elevated temperatures, and gradual losses of weight, UPV, compressive strength, and tensile strength were noted for all tested concretes up to 400 °C, while significantly high rates of losses were observed under high-elevated temperatures between 400 and 800 °C. However, unlike other properties, a significantly high loss of elastic modulus was observed even at low elevated temperatures, due to the formation of internal air voids and hairline cracks because of the evaporation of free water at low temperatures and chemically bound water at high temperatures.

- Up to 400 °C, the loss of compressive strength, tensile strength, elastic modulus, and UPV was in the range of 28–38%, 7–28%, 52–67%, and 20–24%, respectively. The highest losses were observed for CC, and a reasonably close agreement was noted between concretes containing VA and FA. The reason for lower losses among VA and FA concretes is their pozzolanic reactivity at relatively low elevated temperatures.

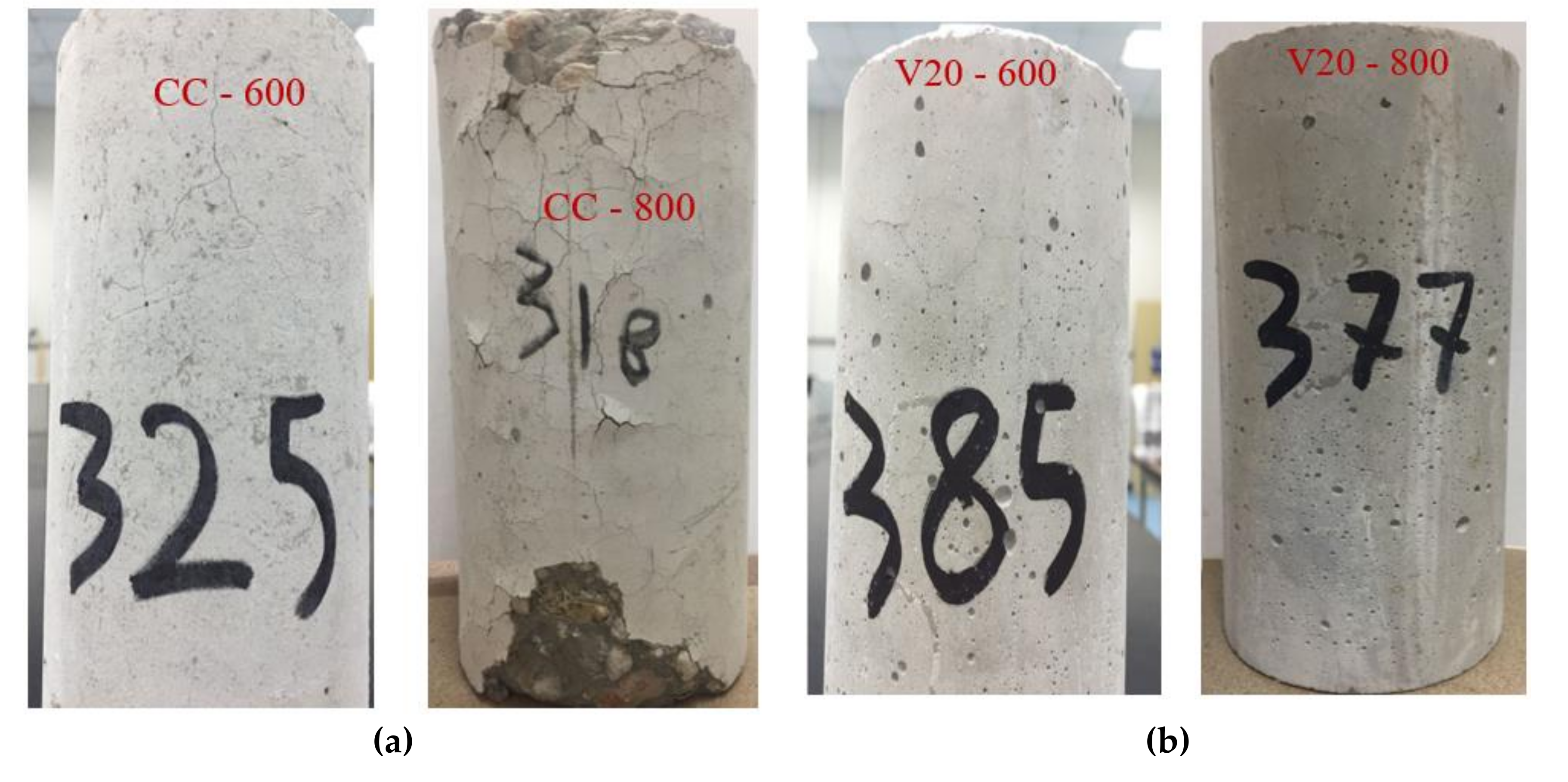

- Between 400 and 600 °C, the respective losses of those properties were abruptly raised for all concretes to 58–64%, 47–58%, 80–81%, and 45–57%, with the highest loss for CC. At such a high temperature, the stability of concrete is seriously affected by the decomposition of CSH and dehydration of Ca(OH)2 to free lime. The relatively lesser loss among concretes with VA or FA than CC was due to their inherited ability to partly replace Ca(OH)2, thus offering a higher resistance to degradation at elevated temperatures.

- Under high exposure temperature from 600 to 800 °C, the rate of high losses continued among all concretes, with values of 87–93%, 73–77%, 93–95%, and 75–77% for compressive strength, tensile strength, elastic modulus, and UPV, respectively. This is because of the large number of wider cracks and severe damage of concrete surfaces at such a high exposure temperature, irrespective of the type of concrete.

- For all concretes, an almost uniform trend of effect of elevated temperature exposure on residual UPV and RCS was noted. Therefore, a linear regression analysis was performed between the residual UPV and RCS of tested concretes. On the basis of the good correlation between the experimental data and regression line, an equation was proposed to use UPV as a nondestructive test to assess the RCS of fire-damaged (up to 800 °C) concrete incorporating VA, FA, and their blends with EAFS.

- The promising performance of concretes containing VA and EAFS before and after exposure to elevated temperature indicates that the use of these materials in construction as a partial substitute of cement can be very useful in terms of saving natural resources and protecting environment. However, it is suggested to extend this research to study the softening behavior of current concrete mixes at elevated temperature through their complete stress–strain curves. On this basis, a relationship between different concrete mechanical properties (strength and strains) can be proposed in terms of elevated temperature. In addition, other aspects of this research such as the influence of specimen dimension, heat conductivity, and heating/cooling rate on thermal damages need to be further explored.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Choi, E.; Shin, Y. The structural behavior and simplified thermal analysis of normal-strength and high-strength concrete beams under fire. Eng. Struct. 2011, 33, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Awal, A.S.M.; Shehu, I.A.; Ismail, M. Effect of cooling regime on the residual performance of high-volume palm oil fuel ash concrete exposed to high temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 98, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, J. Residual strength of hybrid-fiber-reinforced high-strength concrete after exposure to high temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 1065–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arioz, O. Effects of elevated temperatures on properties of concrete. Fire Saf. J. 2007, 42, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamonite, P.; Gambarova, P.G.; Meda, A. Today’s concretes exposed to fire-test results and sectional analysis. Struct. Concr. J. 2008, 9, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, D.; Zhan, B.; Poon, C.S. Thermal and residual mechanical profile of recycled aggregate concrete prepared with carbonated concrete aggregates after exposure to elevated temperatures. Fire Mater. 2018, 42, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bingol, A.F.; Gul, R. Effect of elevated temperatures and cooling regimes on normal strength concrete. Fire Mater. 2009, 33, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhar, S.; Cheng, T.W.; Luhar, I. Incorporation of natural waste from agricultural and aquacultural farming as supplementary materials with green concrete: A review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 175, 107076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, K.; Gupta, N. Application of domestic & industrial waste materials in concrete: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 26, 2926–2931. [Google Scholar]

- Celik, K.; Jackson, M.D.; Mancio, M.; Meral, C.; Emwas, A.H.; Mehta, P.K.; Monteiro, P.J.M. High-volume natural volcanic pozzolan and limestone powder as partial replacements for portland cement in self-compacting and sustainable concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2014, 45, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, K.; Ullah, M.F.; Shahzada, K.; Amin, M.N.; Bibi, T.; Wahab, N.; Aljaafari, A. Effective use of micro-silica extracted from rice husk ash for the production of high-performance and sustainable cement mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 258, 119589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasanipour, H.; Aslani, F.; Taherinezhad, J. Effect of silica fume on durability of self-compacting concrete made with waste recycled concrete aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 227, 116598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefni, Y.; Zaher, Y.A.E.; Wahab, M.A. Influence of activation of fly ash on the mechanical properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 172, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.N.; Murtaza, T.; Shahzada, K.; Khan, K.; Adil, M. Pozzolanic Potential and Mechanical Performance of Wheat Straw Ash Incorporated Sustainable Concrete. Sustainability 2019, 11, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, K.; Amin, M.N.; Saleem, M.U.; Qureshi, H.J.; Al-Faiad, M.A.; Qadir, M.G. Effect of Fineness of Basaltic Volcanic Ash on Pozzolanic Reactivity, ASR Expansion and Drying Shrinkage of Blended Cement Mortars. Materials 2019, 12, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salvador, R.P.; Rambo, D.A.S.; Bueno, R.M.; Silva, K.T.; Figueiredo, A.D.D. On the use of blast-furnace slag in sprayed concrete applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 218, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, A.; Memon, S.A.; Lo, T.Y. Mechanical performance, durability, qualitative and quantitative analysis of microstructure of fly ash and Metakaolin mortar at elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, K.W.; Marzouk, H.M. Properties of Mass Concrete Containing Fly Ash at High Temperatures. ACI J. Proc. 1979, 76, 537–550. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, F.U.A.; Vimonsatit, V. Effect of cooling methods on residual compressive strength and cracking behavior of fly ash concretes exposed at elevated temperatures. Fire Mater. 2016, 40, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Ali, M. Improvement in concrete behavior with fly ash, silica-fume and coconut fibres. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 203, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, N.; Siddique, R. Effects of elevated temperatures on properties of self-compacting-concrete containing fly ash and spent foundry sand. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 34, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitake, B.I.; Wong, H.; Ishida, T.; Nassif, A.Y. Thermal stress of high volume fly-ash (HVFA) concrete made with limestone aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 71, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitake, I.; Komure, H.; Nassif, A.Y.; Fukumoto, S. Tensile properties of high volume fly-ash (HVFA) concrete with limestone aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 49, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Yan, D.; Li, X. Flexural properties after exposure to elevated temperatures of a ground granulated blast furnace slag concrete incorporating steel fibers and polypropylene fibers. Fire Mater. 2014, 38, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y. The effects of elevated temperature on cement paste containing GGBFS. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2008, 30, 992–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.S.; Azhar, S.; Anson, M.; Wong, Y.L. Comparison of strength and durability performance of normal and high-strength pozzolanic concretes at elevated temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2001, 31, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, B.; Kelestemur, O. Effect of elevated temperature on the mechanical properties of concrete produced with finely ground pumice and silica fume. Fire Saf. J. 2010, 45, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohamad, S.A.; Al-Hamd, R.K.S.; Khaled, T.T. Investigating the effect of elevated temperatures on the properties of mortar produced with volcanic ash. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2020, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, K.M.A. High strength blended cement concrete incorporating volcanic ash: Performance at high temperatures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2006, 28, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurram, N.; Khan, K.; Saleem, M.U.; Amin, M.N.; Akmal, U. Effect of elevated temperatures on mortar with naturally occurring volcanic ash and its blend with electric arc furnace slag. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 2018, 5324036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, M.I.; Alhozaimy, A.M. Properties of natural pozzolan and its potential utilization in environmental friendly concrete. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2011, 38, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA-WBCSD, Cement Technology Roadmap 2009: Carbon Emissions Reductions up to 2050. Geneva, Switzerland. 2009. Available online: https://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/Cement.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2020).

- WBCSD-CSI, Cement Industry Energy and CO2 Performance: Getting the Numbers Right (GNR). WBCSD: Washington, DC, USA. 2009. Available online: https://www.wbcsd.org/Sector-Projects/Cement-Sustainability-Initiative/Resources/Cement-Industry-Energy-and-CO2-Performance (accessed on 19 December 2020).

- Laurent, D.; Al-Nakhebi, Z.A. Reconnaissance for Pozzolan in the Pyroclastic Cores of the Harrats. Bureau de RECHERCHES Geologiques et Minères (BRGM Saudi Arabian Mission); Technical Report 79-JED-18; 1979; p. 60. Available online: https://new.dmmr.gov.sa/mop/Pages/TechnicalReports.aspx (accessed on 19 December 2020).

- Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Guo, W. Volcanic Natural Resources and Volcanic Landscape Protection: An Overview. Karoly Nemeth, Intech Open. 2012. Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/books/updates-in-volcanology-new-advances-in-understanding-volcanic-systems/volcanic-natural-resources-and-volcanic-landscape-protection-an-overview (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Depci, T.; Efe, T.; Tapan, M.; Özvan, A.; Açlan, M.; Uner, T. Chemical characterization of Patnos Scoria (Ağrı, Turkey) and its usability for production of blended cement. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2012, 48, 303–315. [Google Scholar]

- Asiabanha, A.; Bardintzeff, J.; Veysi, S. North Qorveh volcanic field, western Iran: Eruption styles, petrology and geological setting. Miner. Petrol. 2017, 112, 501–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Tsafack, F.; Wandji, P.; Bardintzeff, M.; Bellon, H.; Guillou, H. The mount cameroon stratovolcano (Cameroon volcanic line, Central Africa): Petrology, geochemistry, isotope and age data. Geochem. Mineral. Petrol. Sofia. 2009, 47, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Camp, V.E.; Roobol, M.J.; Hooper, P.R. The Arabian continental alkali basalt province: Part II. Evolution of Harrats Khaybar, Ithnayn and Kura, KSA. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 1991, 103, 363–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moufti, M.R.; Sabtan, A.A.; El-Mahdy, O.R.; Shehata, W.M. Assessment of the industrial utilization of scoria materials in central Harrat Rahat, KSA. Eng. Geol. 2000, 57, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Amin, M.N. Influence of fineness of volcanic ash and its blends with quarry dust and slag on compressive strength of mortar under different curing temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 154, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C618-15. Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C136/C136M-19. Standard Test Method for Sieve Analysis of Fine and Coarse Aggregates; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C127-15. Standard Test Method for Relative Density (Specific Gravity) and Absorption of Coarse Aggregate; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C33/C33M-18. Standard Specification for Concrete Aggregates; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C128-15. Standard Test Method for Relative Density (Specific Gravity) and Absorption of Fine Aggregate; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ACI 363.2R-11. Guide to Quality Control and Assurance of High-Strength Concrete; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ACI 211.4R-08. Guide for Selecting Proportions for High-Strength Concrete Using Portland cement and Other Cementitious Materials; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C192/C192M-19. Standard Practice for Making and Curing Concrete Test Specimens in the Laboratory; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C39/C39M-20. Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, Y.B.; Jang, J.G.; Lee, H.K. Mechanical properties of lightweight concrete made with coal ashes after exposure to elevated temperatures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 72, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C496/C496M-17. Standard Test Method for Splitting Tensile Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C469/C469M-14. Standard Test Method for Static Modulus of Elasticity and Poisson’s Ratio of Concrete in Compression; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C597–16. Standard Test Method for Pulse Velocity Through Concrete; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.C.; Zhang, J.H.; Chen, G.M.; Xie, Z.H. Compressive behaviour of concrete structures incorporating recycled concrete aggregates, rubber crumb and reinforced with steel fibre, subjected to elevated temperatures. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 72, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.M. An investigation of high-volume fly ash concrete blended with slag subjected to elevated temperatures. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 93, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcu, I.B.; Demir, A. Effect of fire and elevated temperature on reinforced concrete structures. Bull. Chamber Civ. Eng. Eskisehir Branch 2002, 16, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, A.K.; Sarker, P.K.; Majhi, S. Effect of elevated temperatures on concrete incorporating ferronickel slag as fine aggregate. Fire Mater. 2019, 43, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- BS EN 1992-1-1. Design of Concrete Structures–Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. Eurocode 2; European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Design Guide of High Strength Concrete to Singapore Standard CP 65, Building and Construction Authority. 2007. Available online: https://www.bca.gov.sg/others/draft_HighStrengthConcrete_DesignGuide.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Aydin, S.; Baradan, B. Effect of pumice and fly ash incorporation of high temperature resistance of cement based mortars. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awal, A.A.; Shehu, I.A. Performance evaluation of concrete containing high volume palm oil fuel ash exposed to elevated temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 76, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lin, Y.; Hsiao, C.; Liu, J. Evaluating residual compressive strength of concrete at elevated temperatures using ultrasonic pulse velocity. Fire Saf. J. 2009, 44, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

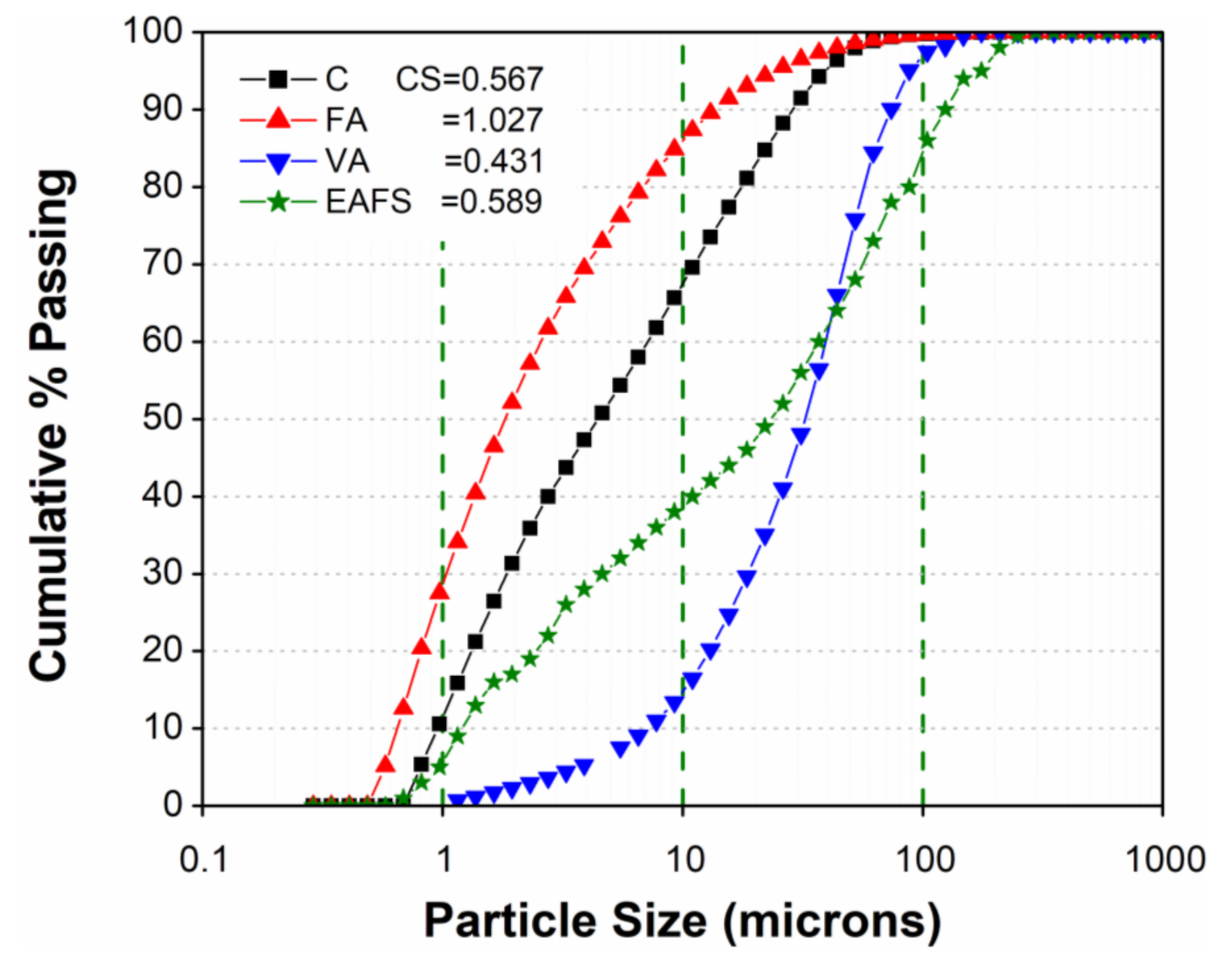

| Cement | FA | VA | EAFS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical properties | ||||

| Specific gravity (g/cm3) | 3.15 | 2.83 | 2.64 | 3.69 |

| Fineness (m2/kg) (Blain) | 344 | - | - | - |

| Fineness (m2/cc) (Microtrac S3500) | 0.5670 | 1.027 | 0.431 | 0.589 |

| Chemical properties (oxides, % by weight) | ||||

| SiO2 | 20.9 | 51.5 | 46.4 | 16.1 |

| Al2O3 | 5.18 | 24.3 | 14.4 | 3.80 |

| Fe2O3 (SiO2 + Al2O3 + Fe2O3) * | 3.04 - | 8.87 84.7 | 12.8 73.6 | 31.7 51.6 |

| CaO | 63.9 | 5.15 | 8.80 | 30.6 |

| MgO | 1.65 | 3.50 | 8.30 | 9.84 |

| Na2O | 0.10 | 2.38 | 3.80 | 0.56 |

| K2O | 0.52 | 1.47 | 1.90 | 0.18 |

| SO3 | 2.61 | 0.23 | 0.80 | Less than 0.1 |

| LOI ** | 2.51 | 0.25 | 2.80 | No Ignitable |

| Compounds (%) | ||||

| C3S | 52.1 | - | - | - |

| C2S | 19.6 | - | - | - |

| C3A | 8.17 | - | - | - |

| C4AF | 8.81 | - | - | - |

| Materials | Mean (µm) | Standard Deviation (µm) | D10 (µm) | D50 (µm) | D90 (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement (C) | 10.58 | 10.01 | 0.954 | 4.440 | 28.63 |

| FA | 5.840 | 4.000 | 0.694 | 1.819 | 13.59 |

| VA | 13.92 | 25.43 | 7.17 | 32.48 | 72.20 |

| EAFS | 10.85 | 25.13 | 1.130 | 24.13 | 130.5 |

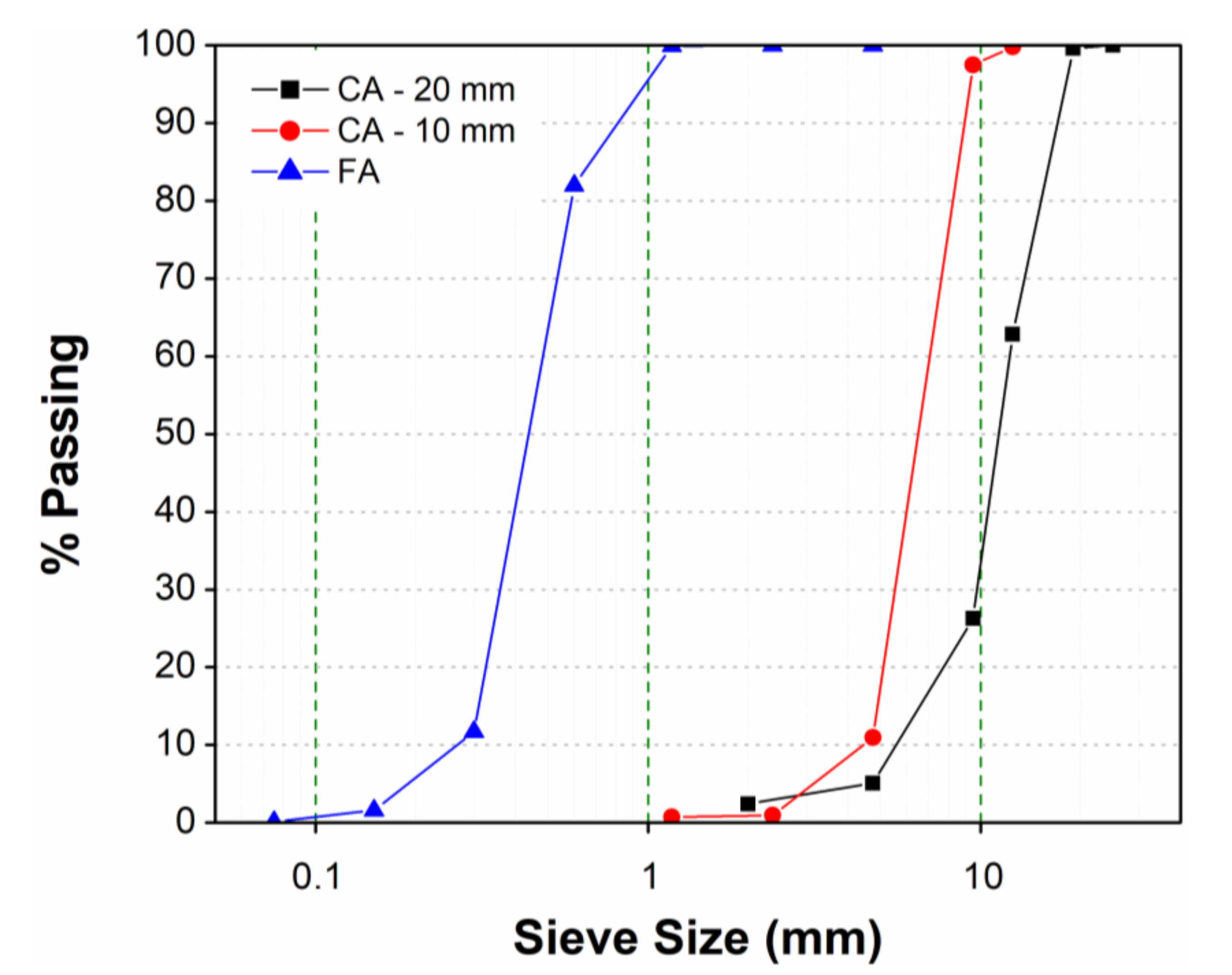

| Materials | Apparent Specific Gravity | Bulk Specific Gravity (SSD) | Bulk Specific Gravity (OD) | Water Absorption Ratio (%) | Fineness Modulus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse aggregate (20 mm) | 2.708 | 2.695 | 2.687 | 0.272 | - |

| Coarse aggregate (10 mm) | 2.706 | 2.685 | 2.674 | 0.300 | - |

| Fine aggregate | 2.678 | 2.613 | 2.574 | 1.415 | 2.05 |

| Mix ID | w/b | a/b | s/a | Binder (kg/m3) | W (kg/m3) | Aggregates (kg/m3) | Admixture ASTM C-494 (Type F) % of Binder | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | VA | FA | EAFS | FA | CA 10 mm | CA 20 mm | ||||||

| CC | 0.35 | 3.57 | 0.40 | 473 | - | - | - | 166 | 670 | 370 | 650 | 1 |

| V20 | 3.57 | 0.40 | 378 | 95 | - | - | 670 | 1.2 | ||||

| F20 | 3.57 | 0.40 | 378 | - | 95 | - | 670 | 0.5 | ||||

| V20S10 | 3.47 | 0.38 | 378 | 95 | - | 47 | 623 | 1.2 | ||||

| F20S10 | 3.53 | 0.39 | 378 | - | 95 | 47 | 650 | 0.5 | ||||

| Fresh properties | ||||||||||||

| Slump (mm) | Air content (%) | Unit weight (kg/m3) | ||||||||||

| CC | 90 | 3.5 | 2417 | |||||||||

| V20 | 120 | 3.1 | 2378 | |||||||||

| F20 | 150 | 2.3 | 2427 | |||||||||

| V20S10 | 120 | 3.5 | 2450 | |||||||||

| F20S10 | 100 | 3.1 | 2446 | |||||||||

| Concrete Specimen ID | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Splitting Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | UPV (m/s) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 Days | 28 Days | 91 Days | 7 Days | 28 Days | 91 Days | 7 Days | 28 Days | 91 Days | 91 Days | |

| CC | 42.6 | 51.4 | 73.1 | 3.96 | 4.93 | 5.04 | 36.0 | 39.5 | 41.6 | 5025 |

| V20 | 36.8 | 49.2 | 68.0 | 3.72 | 4.28 | 4.57 | 37.7 | 36.7 | 41.5 | 5013 |

| F20 | 35.6 | 49.5 | 70.0 | 3.42 | 4.20 | 4.64 | 34.7 | 42.0 | 39.1 | 5062 |

| V20S10 | 37.4 | 46.5 | 74.8 | 3.39 | 4.51 | 4.65 | 32.4 | 33.8 | 40.1 | 5089 |

| F20S10 | 40.9 | 46.9 | 71.8 | 3.20 | 3.81 | 4.43 | 33.4 | 35.4 | 40.6 | 5081 |

| Concrete Specimen ID | T (°C) | Residual Compressive Strength | Residual Splitting Tensile Strength | Residual Elastic Modulus | Residual UPV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPa | Relative (%) | MPa | Relative (%) | GPa | Relative (%) | m/s | Relative (%) | ||

| CC | 20 | 73.1 (3.6) * | 100 | 5.03 (0.11) | 100 | 39.8 (2.0) | 100 | 5021 (7) | 100 |

| 200 | 54.4 (2.5) | 74.0 | 3.97 (0.49) | 78.9 | 25.4 (1.5) | 63.8 | 4529 (67) | 90.2 | |

| 400 | 45.5 (3.6) | 62.2 | 3.61 (0.29) | 71.8 | 12.9 (1.5) | 32.5 | 3704 (19) | 73.8 | |

| 600 | 26.6 (2.5) | 36.4 | 2.15 (0.26) | 42.8 | 3.6 (2.5) | 9.0 | 2137 (46) | 42.6 | |

| 800 | 5.3 (2.0) | 7.2 | 1.29 (0.17) | 25.7 | 2.1 (0.5) | 5.2 | 1183 (14) | 23.6 | |

| V20 | 20 | 68.0 (0.2) | 100 | 4.70 (0.15) | 100 | 39.5 (1.1) | 100 | 4951 (56) | 100 |

| 200 | 51.4 (2.1) | 75.6 | 3.85 (0.43) | 82.0 | 28.1 (2.6) | 71.2 | 4598 (85) | 92.9 | |

| 400 | 46.5 (3.1) | 68.4 | 3.64 (0.14) | 77.5 | 16.9 (3.2) | 42.7 | 3949 (103) | 79.8 | |

| 600 | 28.2 (1.8) | 41.5 | 2.49 (0.20) | 52.9 | 8.0 (1.7) | 20.3 | 2735 (67) | 55.2 | |

| 800 | 8.9 (3.9) | 13.1 | 1.06 (0.38) | 22.6 | 2.5 (0.3) | 6.3 | 1315 (21) | 26.6 | |

| F20 | 20 | 70.0 (4.5) | 100 | 4.49 (0.07) | 100 | 42.3 (4.2) | 100 | 5062 (176) | 100 |

| 200 | 49.1 (1.1) | 70.2 | 3.96 (0.31) | 88.1 | 30.4 (1.8) | 71.8 | 4577 (110) | 90.4 | |

| 400 | 50.2 (1.3) | 71.7 | 4.08 (0.12) | 90.9 | 16.7 (3.2) | 39.4 | 4057 (102) | 80.1 | |

| 600 | 28.7 (2.3) | 41.0 | 2.40 (0.21) | 53.3 | 6.5 (0.3) | 15.3 | 2565 (100) | 50.7 | |

| 800 | 7.6 (3.6) | 10.8 | 1.04 (0.42) | 23.1 | 2.0 (0.3) | 4.7 | 1286 (90) | 25.4 | |

| V20S10 | 20 | 74.8 (3.5) | 100 | 4.66 (0.06) | 100 | 38.7 (2.3) | 100 | 5089 (145) | 100 |

| 200 | 52.3 (2.0) | 69.9 | 4.03 (0.44) | 86.6 | 30.5 (3.2) | 78.7 | 4652 (87) | 91.4 | |

| 400 | 48.1 (5.0) | 64.3 | 3.89 (0.10) | 83.5 | 18.3 (1.7) | 47.4 | 3976 (77) | 78.1 | |

| 600 | 26.6 (1.0) | 35.6 | 2.18 (0.08) | 46.8 | 6.7 (0.3) | 17.4 | 2711 (87) | 53.3 | |

| 800 | 9.7 (2.2) | 13.0 | 1.16 (0.32) | 24.9 | 2.7 (0.4) | 7.0 | 1230 (48) | 24.2 | |

| F20S10 | 20 | 71.8 (1.6) | 100 | 4.46 (0.05) | 100 | 40.7 (1.5) | 100 | 5103 (67) | 100 |

| 200 | 52.9 (4.1) | 73.7 | 4.02 (0.25) | 90.2 | 30.9 (2.1) | 76.0 | 4764 (120) | 93.4 | |

| 400 | 49.8 (2.3) | 69.4 | 4.13 (0.20) | 92.6 | 14.9 (2.5) | 36.6 | 4073 (87) | 79.8 | |

| 600 | 29.4 (2.5) | 41.0 | 1.88 (0.16) | 42.3 | 5.8 (0.2) | 14.2 | 2598 (86) | 50.9 | |

| 800 | 8.6 (3.8) | 12.0 | 1.19 (0.35) | 26.7 | 2.2 (0.5) | 5.4 | 1184 (62) | 23.2 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amin, M.N.; Khan, K. Mechanical Performance of High-Strength Sustainable Concrete under Fire Incorporating Locally Available Volcanic Ash in Central Harrat Rahat, Saudi Arabia. Materials 2021, 14, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14010021

Amin MN, Khan K. Mechanical Performance of High-Strength Sustainable Concrete under Fire Incorporating Locally Available Volcanic Ash in Central Harrat Rahat, Saudi Arabia. Materials. 2021; 14(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmin, Muhammad Nasir, and Kaffayatullah Khan. 2021. "Mechanical Performance of High-Strength Sustainable Concrete under Fire Incorporating Locally Available Volcanic Ash in Central Harrat Rahat, Saudi Arabia" Materials 14, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14010021

APA StyleAmin, M. N., & Khan, K. (2021). Mechanical Performance of High-Strength Sustainable Concrete under Fire Incorporating Locally Available Volcanic Ash in Central Harrat Rahat, Saudi Arabia. Materials, 14(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14010021