Influence of Non-Metallic Inclusions on Bending Fatigue Strength of High-Quality Carbon Constructional Steel Heated in an Industrial Electric Arc Furnace

Abstract

:1. Introduction

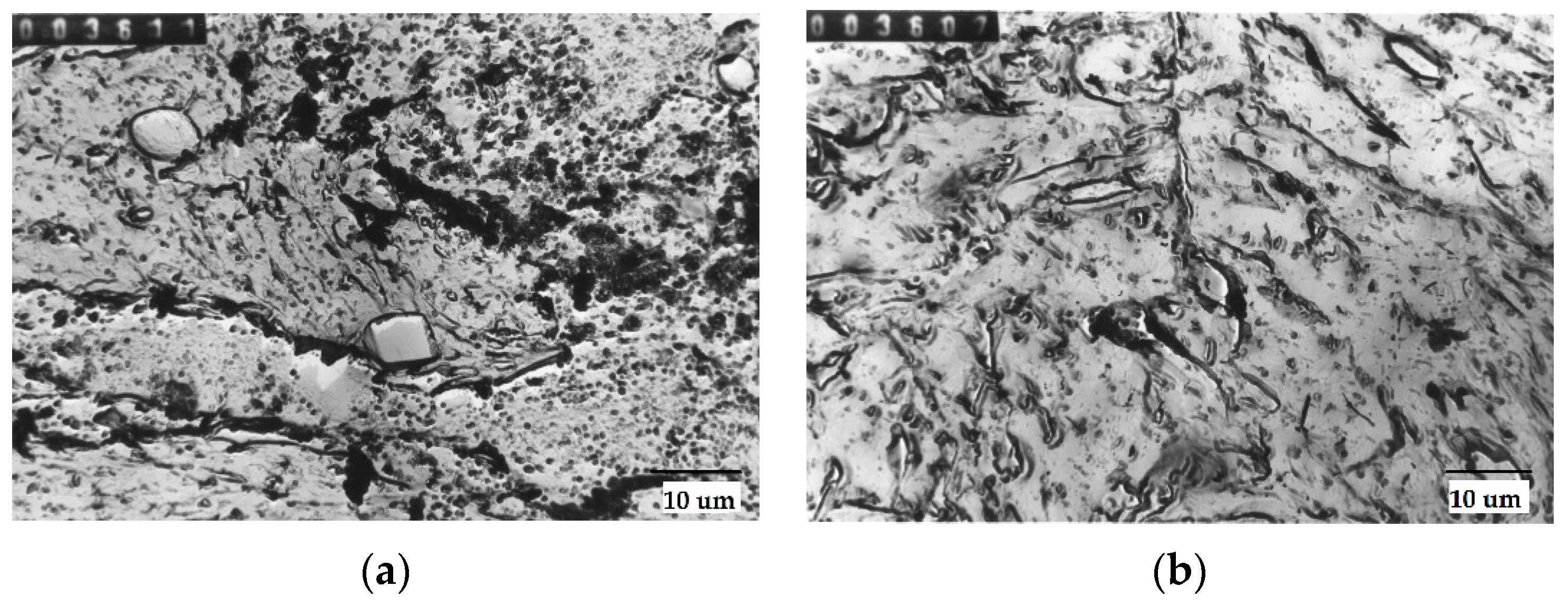

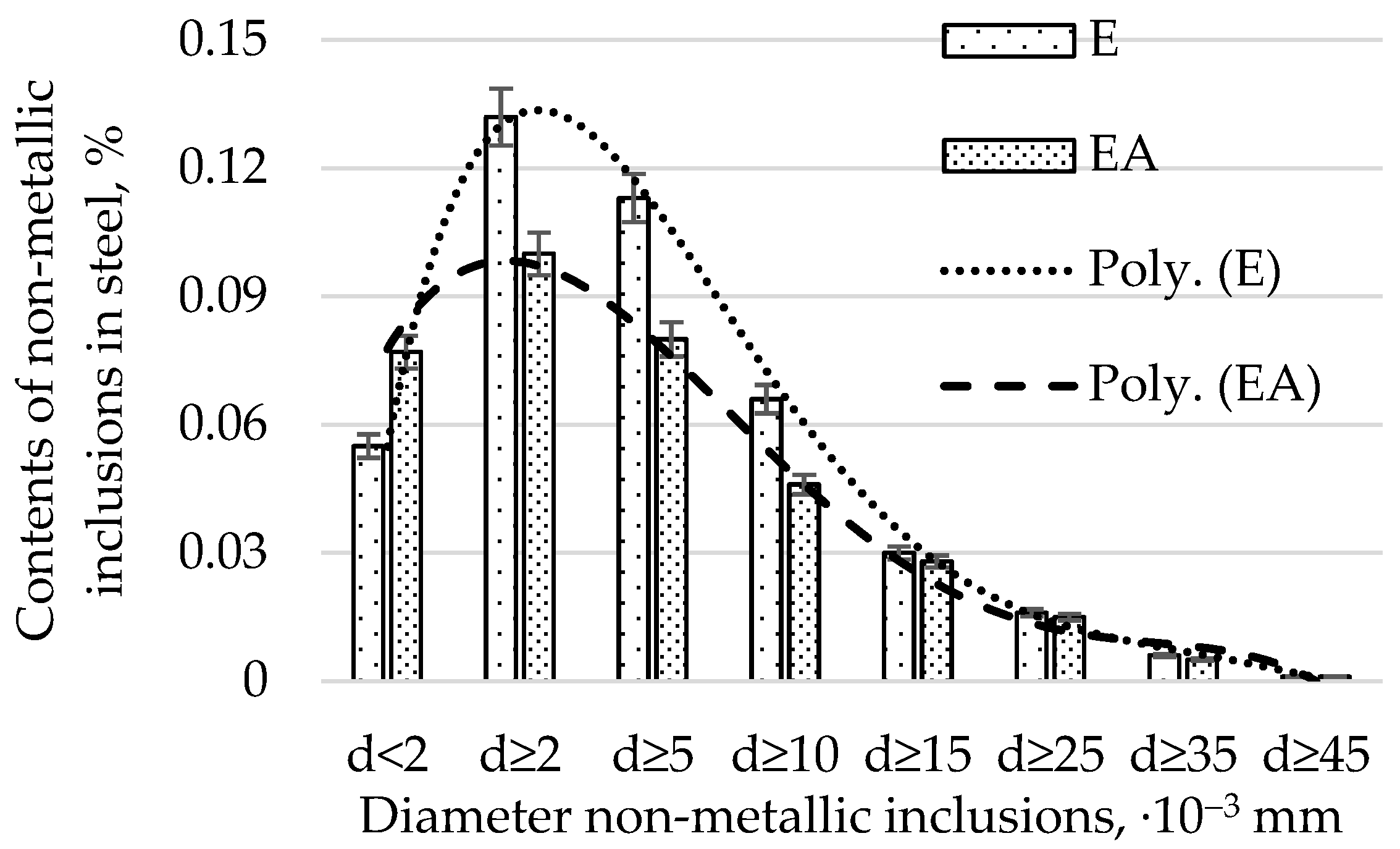

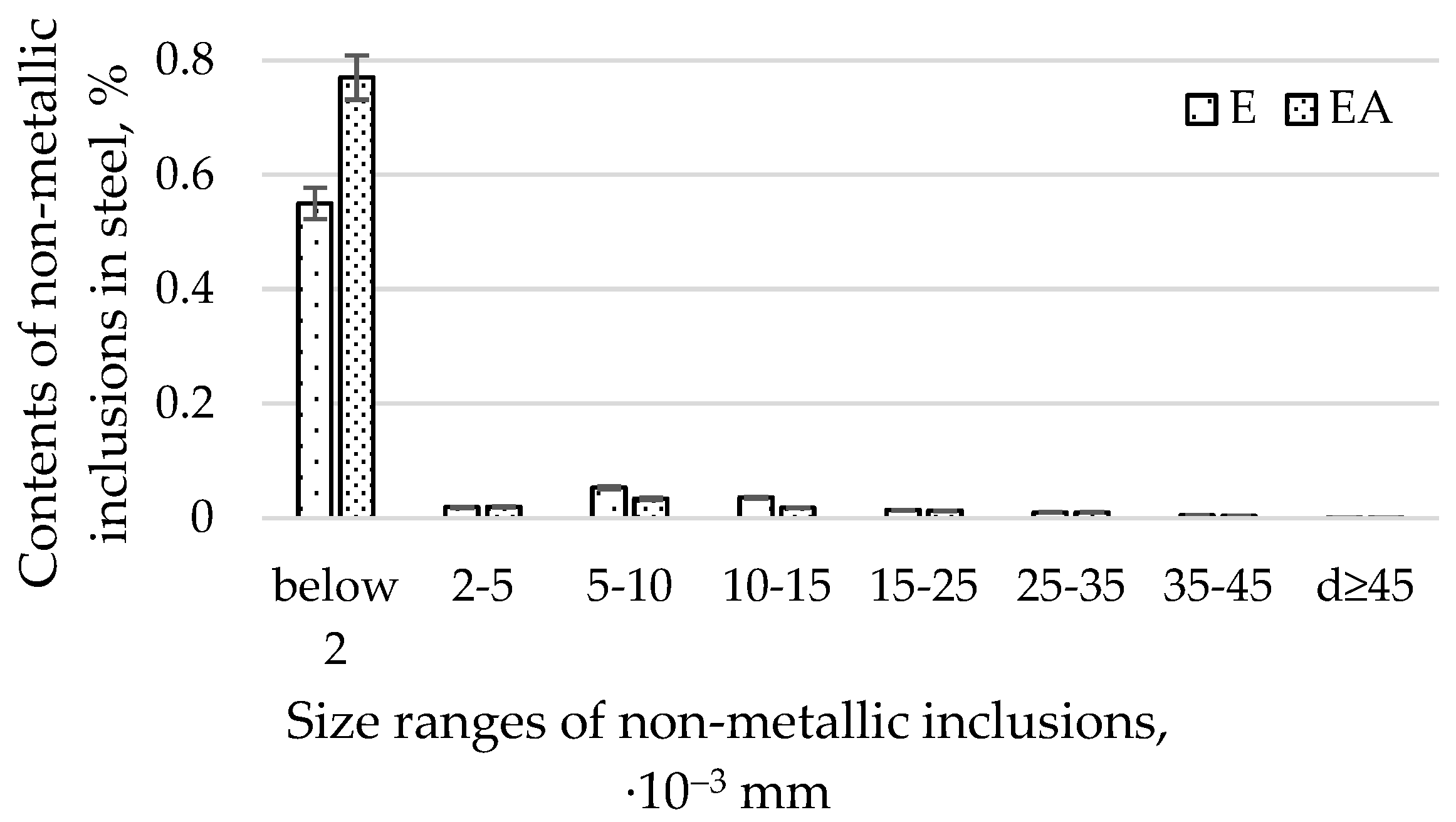

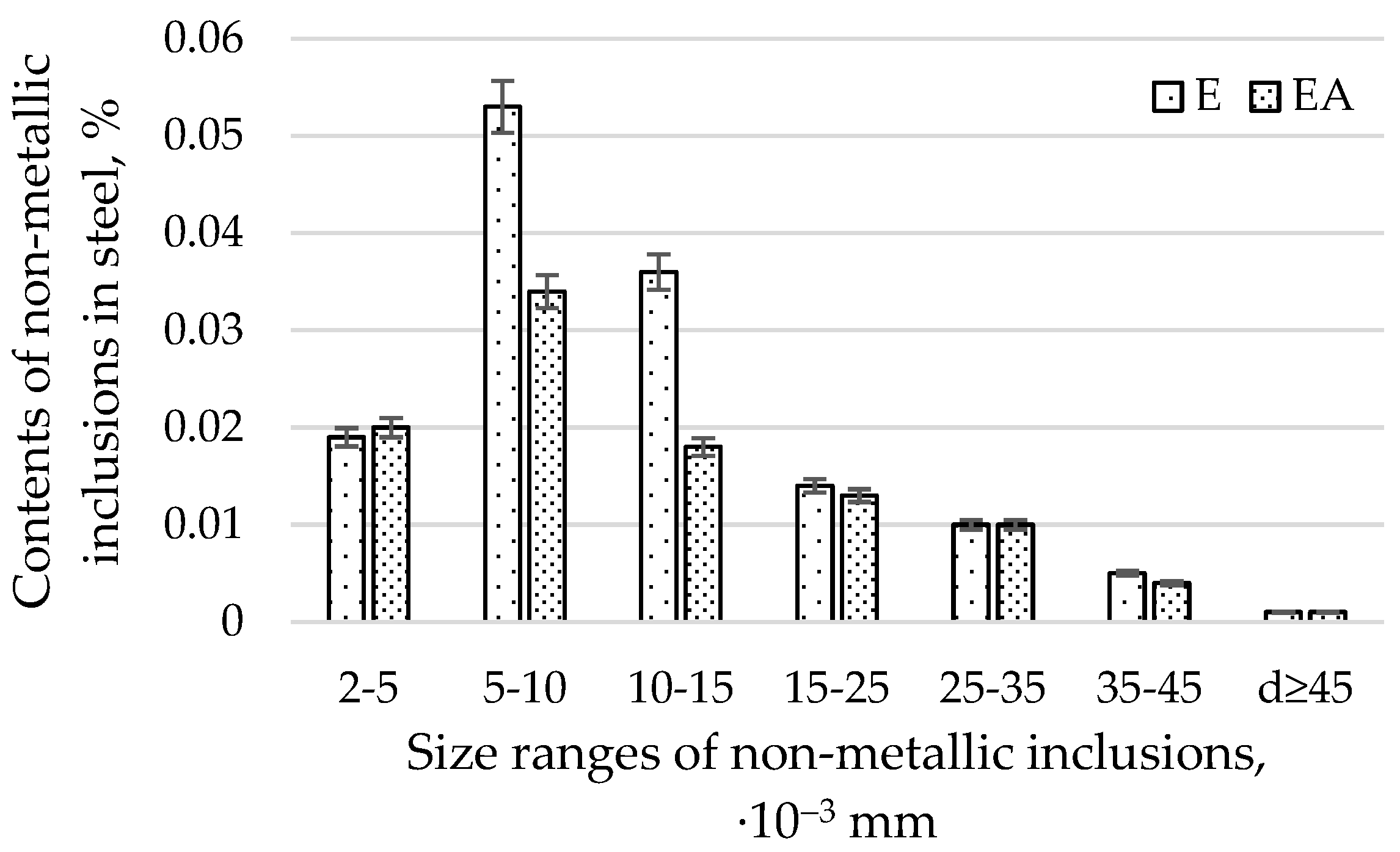

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hren, I.; Michna, Š.; Novotný, J.; Michnová, L. Comprehensive analysis of the coated component from a FORD engine. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 21, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricín, D.; Kříž, A. Influence of the Boriding Process on the Properties and the Structure of the Steel S265 and the Steel X6CrNiTi18-10. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 21, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipiński, T.; Ulewicz, R. The effect of the impurities spaces on the quality of structural steel working at variable loads. Open Eng. 2021, 11, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłysz, S. Selected problems of fatigue of materials and constructions elements. Tech. Sci. 2005, 8, 141–164. [Google Scholar]

- Jonšta, P.; Jonšta, Z.; Brožová, S.; Ingaldi, M.; Pietraszek, J.; Klimecka-Tatar, D. The Effect of Rare Earth Metals Alloying on the Internal Quality of Industrially Produced Heavy Steel Forgings. Materials 2021, 14, 5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jopek, M. Determination of Carbon Steel Dynamic Properties. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 21, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźny, A. Selected problems of managing work safety-case study. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2020, 26, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blikharskyy, Y.; Selejdak, J.; Kopiika, N. Corrosion fatigue damages of rebars under loading in time. Materials 2021, 14, 3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Deng, S.; Han, X.; Huang, S. Effect of material defects on crack initiation under rolling contact fatigue in a bearing ring. Tribol. Int. 2013, 66, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S. Fatigue of Materials; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Krynke, M. Management optimizing the costs and duration time of the process in the production system. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2021, 27, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenkovskiy, T.M.; Kulyk, V.V.; Duriagina, Z.A.; Kovalchuk, R.A.; Topilnytskyy, V.H.; Vira, V.V.; Tepla, T.L. Mode I and mode II fatigue crack growth resistance characteristics of high tempered 65G steel. Arch. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 84, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kováčiková, P.; Dubec, A.; Kuricová, J. The microstructural study of a damaged motorcycle gear wheel. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 21, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malashchenko, V.; Strilets, O.; Strilets, V.; Kłysz, S. Investigation of the energy effectiveness of multistage differential gears when the speed is changed by the carrier. Diagnostyka 2019, 20, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halford, G.L. Low Cycle Thermal Fatigue; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1986.

- Ivanytskyj, Y.L.; Lenkovskiy, T.M.; Molkov, Y.V.; Kulyk, V.V.; Duriagina, Z.A. Influence of 65G steel microstructure on crack faces friction factor under mode fatigue fracture. Arch. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 82, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blikharskyy, Z.; Brózda, K.; Selejdak, J. Effectivenes of Strengthening Loaded RC Beams with FRCM System. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2018, 64, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, J.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, R.; Li, G.; Wang, H.; Fang, Q.; Wang, X. Microstructures and Tensile Properties of 9Cr-F/M Steel at Elevated Temperatures. Materials 2022, 15, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.S. Roles of microstructure in fatigue crack initiation. Int. J. Fatigue 2010, 32, 1428–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulewicz, R.; Szataniak, P.; Novy, F. Fatigue properties of wear resistant martensitic steel. In Proceedings of the METAL 2014—23rd International Conference on Metallurgy and Materials, Brno, Czech Republic, 21–23 May 2014; pp. 784–789. [Google Scholar]

- Lipiński, T.; Wach, A. Effect Size Proportions and Distances Between the Non-metallic Inclusions on Bending Fatigue Strength of Structural Steel. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Metallurgy and Materials, Metal 2015, Brno, Czech Republic, 3–5 June 2015; pp. 754–760. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, W.; Geng, R.; Zhi, J.; Li, J.; Huang, F. Oxide Metallurgy Technology in High Strength Steel: A Review. Materials 2022, 15, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, M.; Niżnik-Harańczyk, B.; Pogorzałek, J. Influence of steel smelting technology with the addition of 3 ÷ 5% Al alloy on the type and morphology of non-metallic inclusions. Work. Iron Metall. Inst. 2016, 68, 24–32. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Gulyakov, V.S.; Vusikhis, A.S.; Kudinov, D.Z. Nonmetallic Oxide Inclusions and Oxygen in the Vacuum_Jet Refining of Steel. Steel Transl. 2012, 42, 781–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipiński, T.; Wach, A. Influence of outside furnace treatment on purity medium carbon steel. In Proceedings of the METAL 2014—23rd International Conference on Metallurgy and Materials, Brno, Czech Republic, 21–23 May 2014; pp. 738–743. [Google Scholar]

- Roiko, A.; Hänninen, H.; Vuorikari, H. Anisotropic distribution of non-metallic inclusions in forged steel roll and its influence on fatigue limit. Int. J. Fatigue 2012, 41, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Qian, D.; Yin, F.; Wang, F. Enhanced Impact Toughness of Previously Cold Rolled High-Carbon Chromium Bearing Steel with Rare Earth Addition. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 8178–8187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipiński, T.; Wach, A. The effect of fine non-metallic inclusions on the fatigue strength of structural steel Terms and conditions. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2015, 60, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Y. Metal Fatigue. Effects of Small Defects and Inclusions; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Spriestersbach, D.; Grad, P.; Kerscher, E. Influence of different non-metallic inclusion types on the crack initiation in high-strength steels in the VHCF regime. Int. J. Fatigue 2014, 64, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipiński, T. Effect of the spacing between submicroscopic oxide impurities on the fatigue strength of structural steel. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2015, 60, 2385–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macek, W.; Szala, M.; Trembacz, J.; Branco, R.; Costa, J. Effect of non-zero mean stress bending-torsion fatigue on fracture surface parameters of 34CrNiMo6 steel notched bars. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2020, 26, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, F.; Umar, M.; Elagin, V.; Kirschner, M.; Hoffmann, F.; Guk, S.; Prahl, U. Influence of non-metallic inclusions on local deformation and damage behavior of modified 16MnCrS5 steel. Crystals 2022, 12, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipiński, T. The effect of the diameter and spacing between impurities on the fatigue strength coefficient of structural steel. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2018, 63, 519–524. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, Y.; Kodama, S.; Konuma, S. Quantitative evaluation of effects of non-metallic inclusions on fatigue strength of high strength steels, I: Basic fatigue mechanism and fatigue fracture stress and the size and location of non-metallic inclusions. Int. J. Fatigue 1989, 11, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipiński, T.; Wach, A. Influence of inclusions on bending fatigue strength coefficient the medium carbon steel melted in an electric furnace. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2020, 26, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao-Fei, H.; Cheng-Fei, H.; Le, X.; Mao-Qiu, W. Effect of total oxygen on the nonmetallic inclusion of gear steel. Chin. J. Eng. 2021, 43, 537–544. [Google Scholar]

- Foletti, S.; Beretta, S.; Tarantino, M.G. Multiaxial fatigue criteria versus experiments for small crack under rolling contact fatigue. Int. J. Fatigue 2014, 58, 181–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipiński, T.; Wach, A. Effect of the impurities on the bending fatigue strength of structural steel. Eng. Rural. Dev. 2015, 14, 784–789. [Google Scholar]

- Di Schino, A. Analysis of phase transformation in high strength low alloyed steels. Metalurgija 2017, 56, 349–352. [Google Scholar]

- Kalisz, D.; Migas, P.; Karbowniczek, M.; Moskal, M.; Hornik, A. Influence of selected deoxidizers on chemical composition of molten inclusions in liquid steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 1479–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Ponson, L.; Osovski, S.; Bouchaud, E.; Tvergaard, V.; Needleman, A. Effect of inclusion density on ductile fracture toughness and roughness. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2014, 63, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.H.; Richardson, A.D.; Wang, L.; Wood, R.J.K.; Anderson, W.B. Confirming subsurface initiation at non-metallic inclusions as one mechanism for white etching crack (WEC) formation. Tribol. Int. 2014, 75, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Y.; Nomoto, T.; Ueda, T. Factors influencing the mechanism of super long fatigue failure in steels. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 1999, 22, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.R. Fundamentals of Modern Fatigue Analysis for Design. In Fatigue and Fracture; ASM Handbook; ASM International: Almere, The Netherlands, 1996; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Lipiński, T. Bending fatigue strength coefficient the low carbon steel with impurities. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2018, 21, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chubukov, M.Y.; Rutskiy, D.V.; Uskov, D.P. Analyzing the features of non-metallic inclusion distribution in Ø410 mm continuously cast billets of low carbon steel grades. Mater. Sci. Forum 2019, 973, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuartas, M.; Ruiz, E.; Ferreño, D.; Setién, J.; Arroyo, V.; Gutiérrez-Solana, F. Machine learning algorithms for the prediction of non-metallic inclusions in steel wires for tire reinforcement. J. Intell. Manuf. 2021, 32, 1739–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipiński, T.; Wach, A. The effect of the production processes and heat processing parameters on the fatique strength of high-grade medium-carbon steel. Arch. Foundry Eng. 2012, 12, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr | Ni | Mo | Cu | B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | 0.26 | 0.25 | 1.19 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.003 |

| EA | 0.23 | 0.29 | 1.22 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.003 |

| Technological Process | Statistical Parameter | Al2O3 | SiO2 | MnO | MgO | CaO | FeO | Cr2O3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | arithmetic average | 41.7 | 14.4 | 7.10 | 7.9 | 9.3 | 8.7 | 10.5 |

| standard deviation | 2.01 | 1.68 | 1.95 | 1.75 | 1.27 | 2.97 | 2.08 | |

| EA | arithmetic average | 39.3 | 13.2 | 8.5 | 9.7 | 10.3 | 9.6 | 9.1 |

| standard deviation | 2.06 | 1.45 | 2.26 | 0.82 | 1.57 | 2.25 | 1.25 |

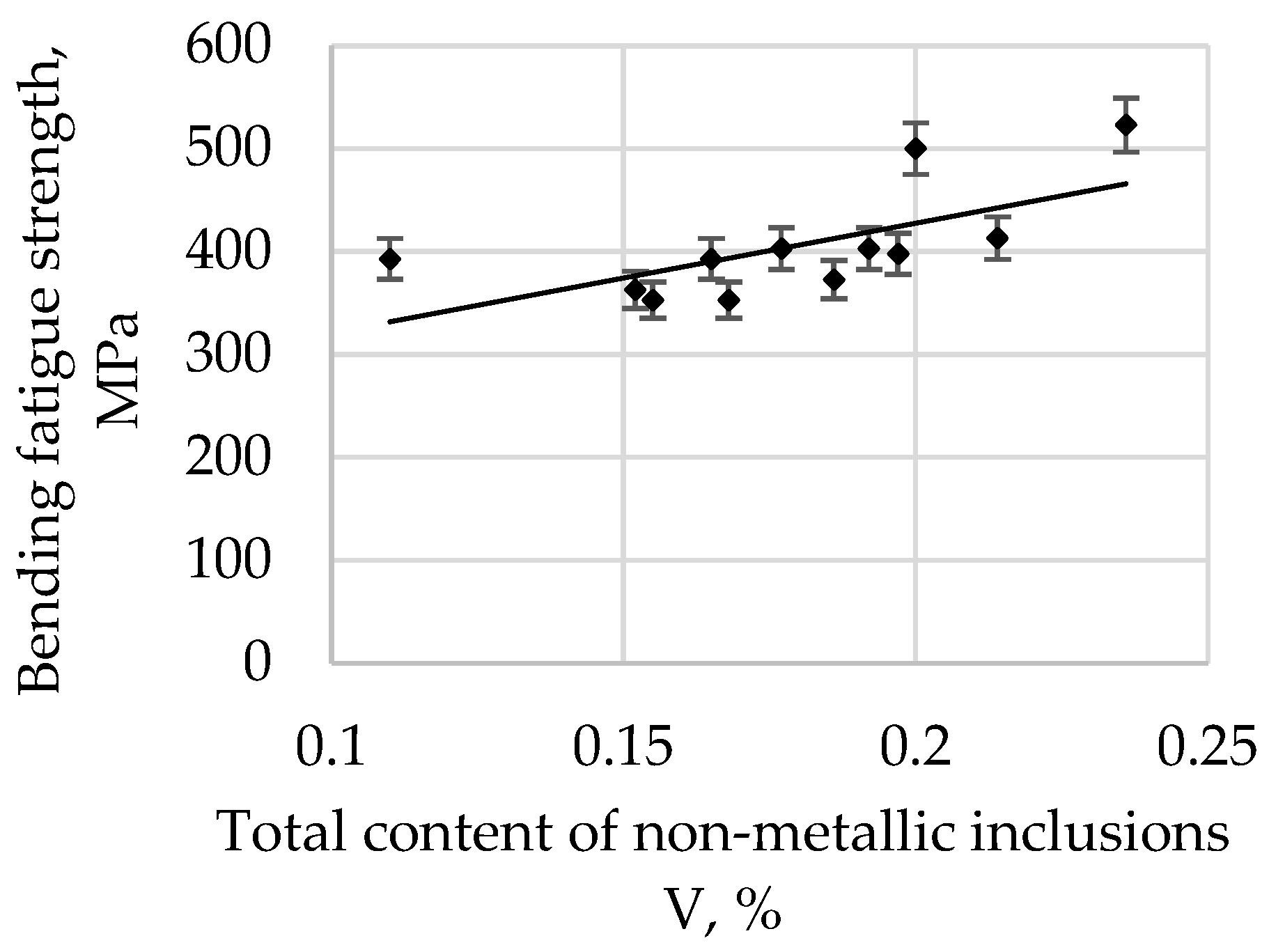

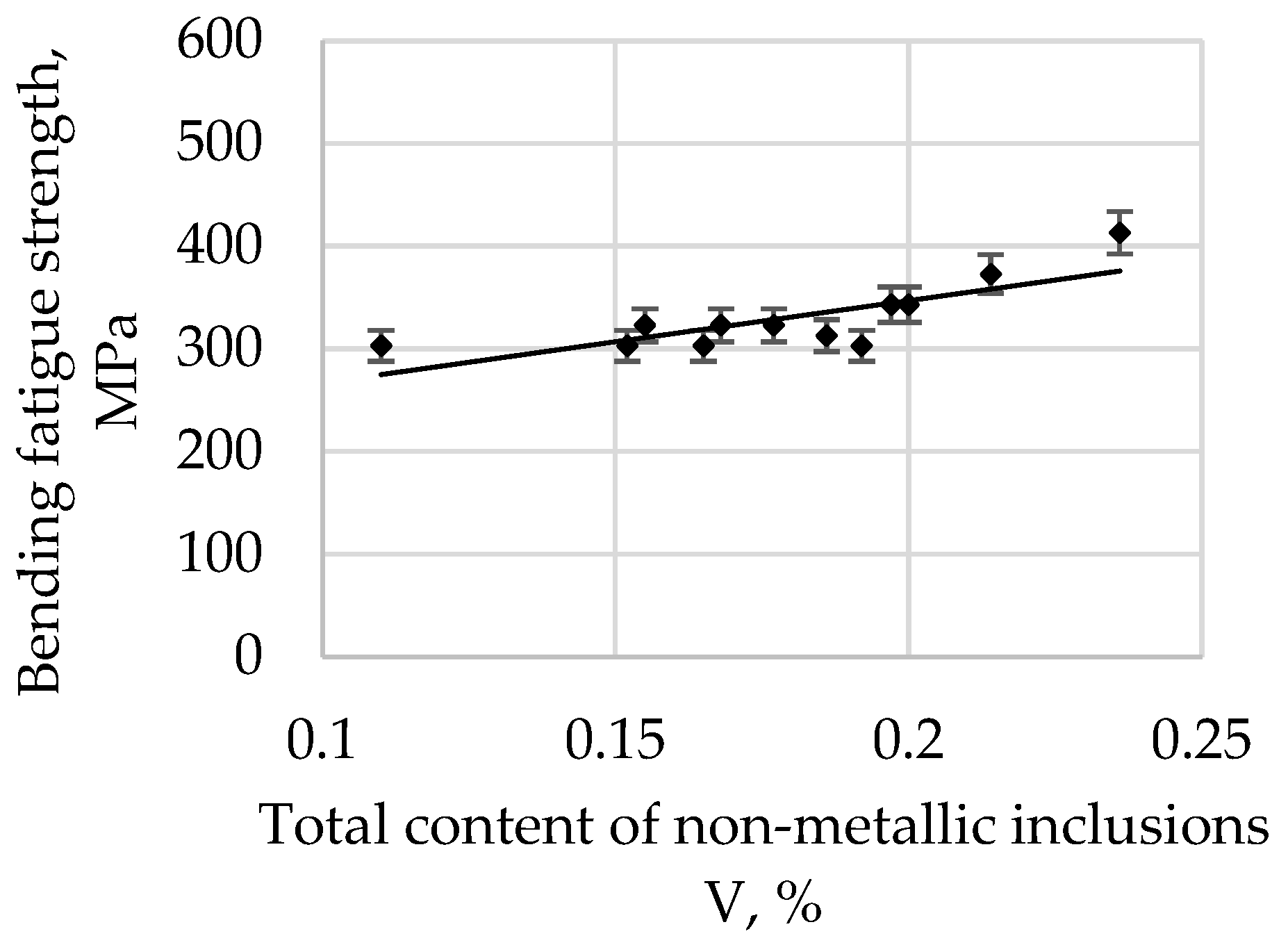

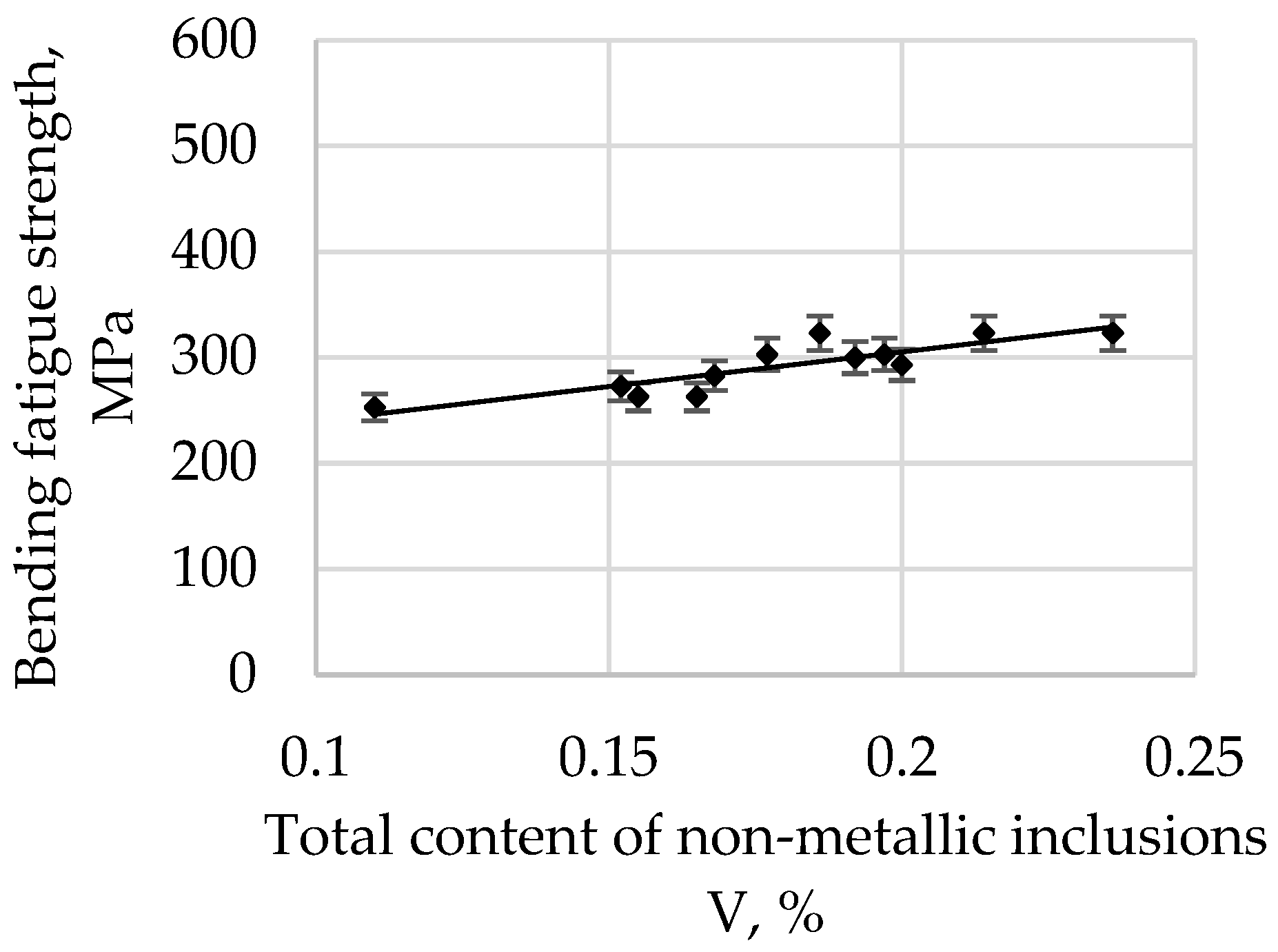

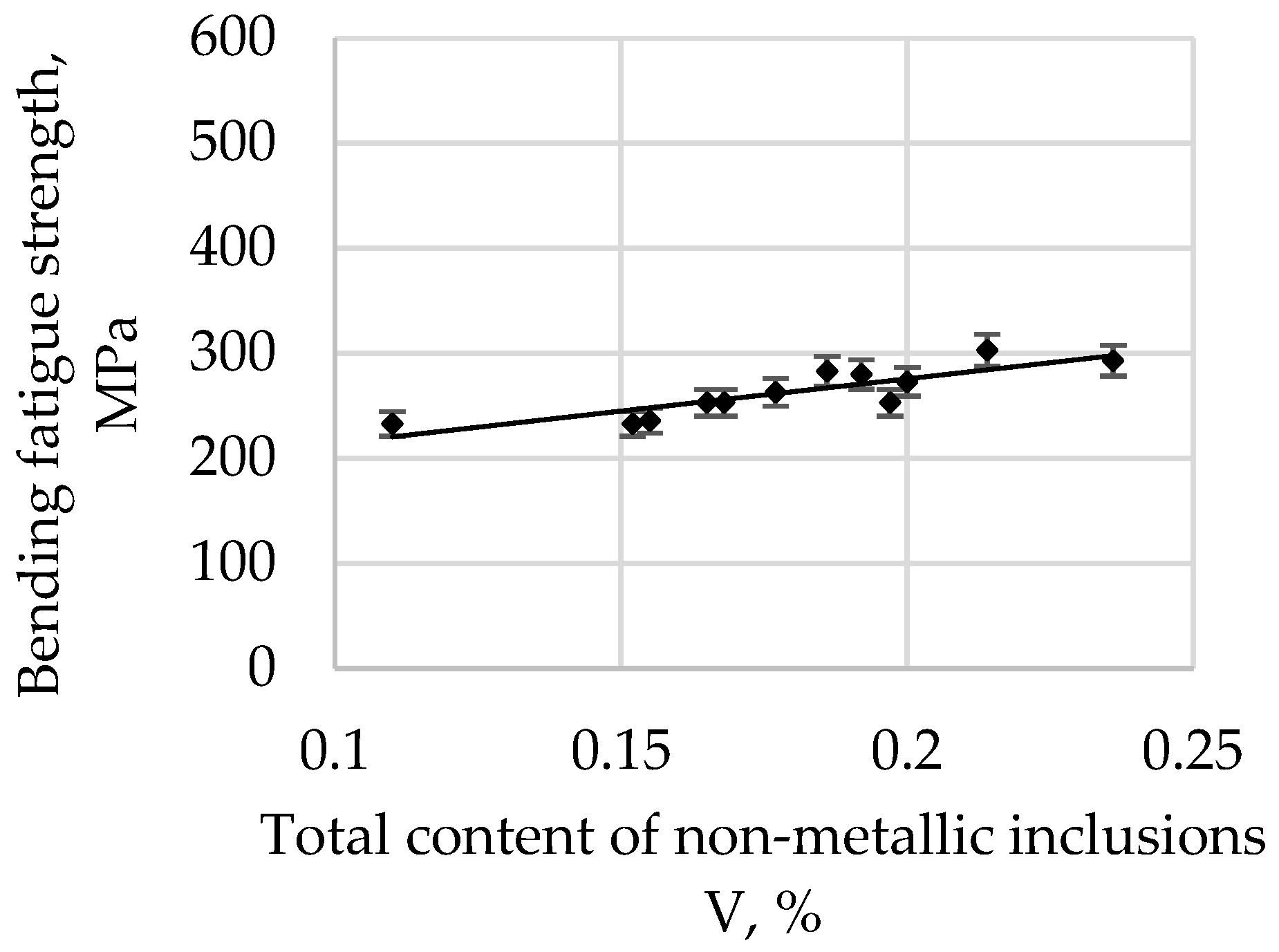

| Tempering Temperature °C | Regression Coefficient a (1) | Regression Coefficient b (1) | Correlation Coefficient r | Degree of Dissipation zgo around Regression δ [MPa] (3) | tα=0.05 Calculated by (2) | tα=0.05 from Student’s t-Distribution for p = (n − 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 | 1062 | 215.22 | 0.6506 | 81.33394572 | 2.841371571 | |

| 300 | 636.12 | 234.84 | 0.7094 | 41.47079098 | 3.338242423 | |

| 400 | 802.18 | 186.64 | 0.7831 | 41.80383589 | 4.176340892 | 2.201 |

| 500 | 656.55 | 174.17 | 0.8642 | 25.08698158 | 5.696583502 | |

| 600 | 614.64 | 152.77 | 0.8552 | 24.44294019 | 5.472482558 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lipiński, T. Influence of Non-Metallic Inclusions on Bending Fatigue Strength of High-Quality Carbon Constructional Steel Heated in an Industrial Electric Arc Furnace. Materials 2022, 15, 6140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15176140

Lipiński T. Influence of Non-Metallic Inclusions on Bending Fatigue Strength of High-Quality Carbon Constructional Steel Heated in an Industrial Electric Arc Furnace. Materials. 2022; 15(17):6140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15176140

Chicago/Turabian StyleLipiński, Tomasz. 2022. "Influence of Non-Metallic Inclusions on Bending Fatigue Strength of High-Quality Carbon Constructional Steel Heated in an Industrial Electric Arc Furnace" Materials 15, no. 17: 6140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15176140

APA StyleLipiński, T. (2022). Influence of Non-Metallic Inclusions on Bending Fatigue Strength of High-Quality Carbon Constructional Steel Heated in an Industrial Electric Arc Furnace. Materials, 15(17), 6140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15176140