Research Progress on Microstructure Evolution and Strengthening-Toughening Mechanism of Mg Alloys by Extrusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Magnesium Alloy Extrusion Process and Advantages

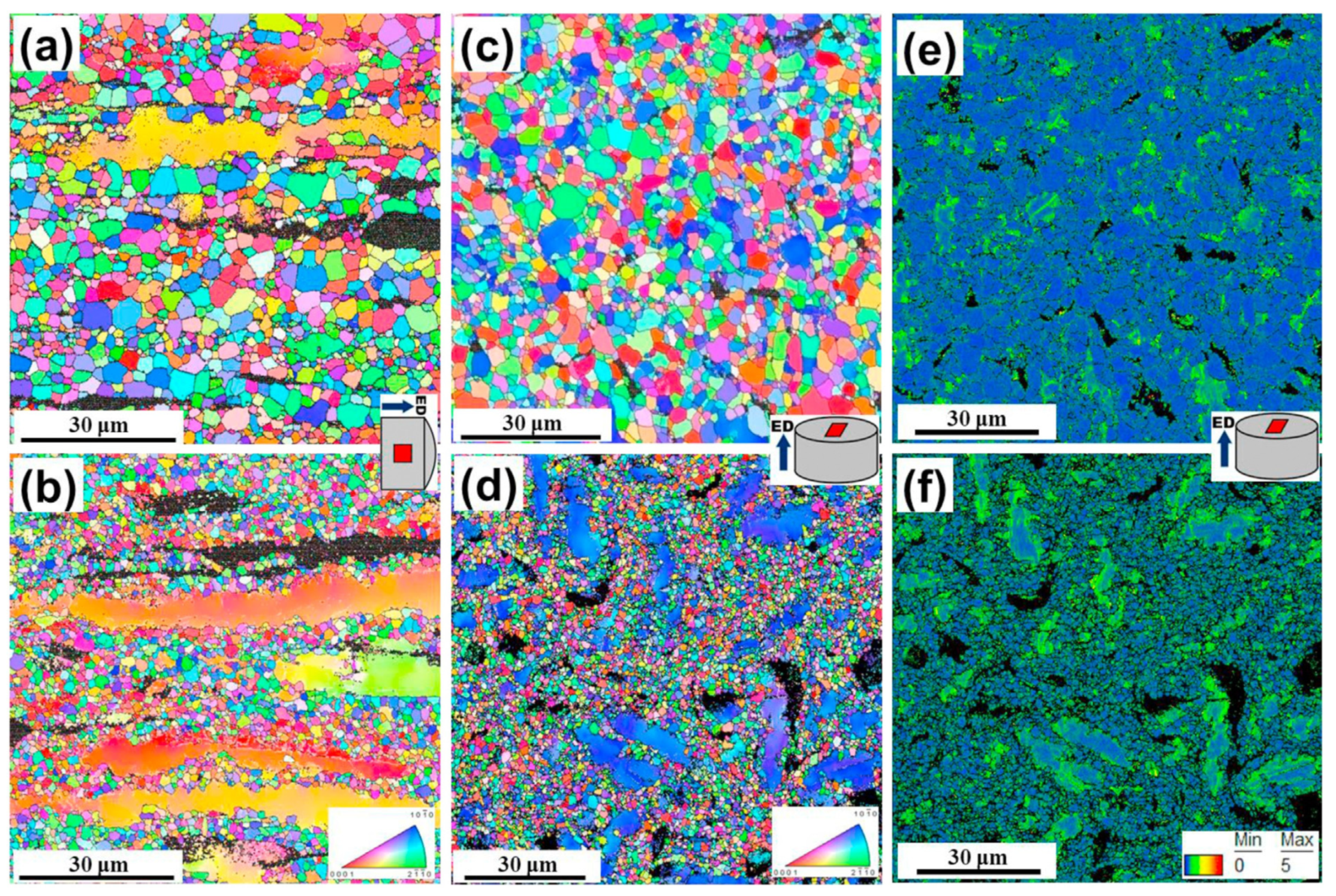

2.1. Direct Extrusion

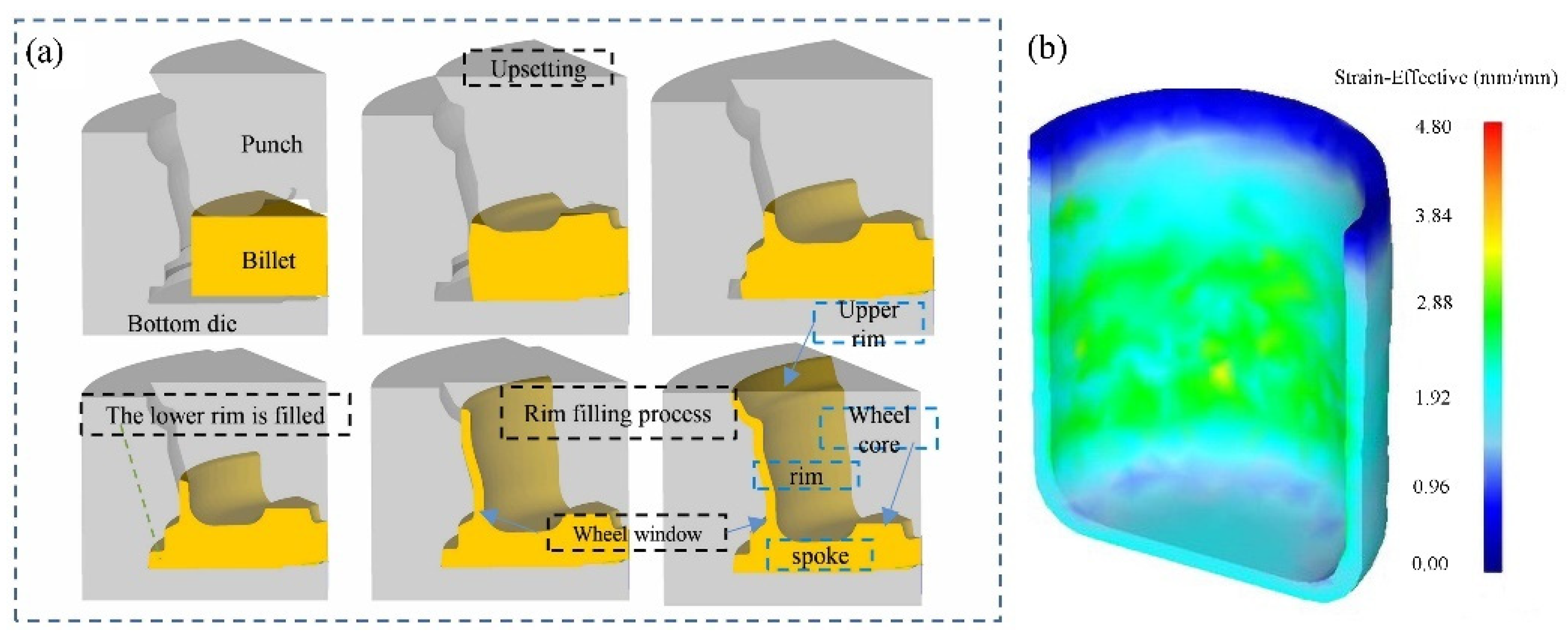

2.2. Indirect Extrusion

2.3. Equal Channel Angular Pressing

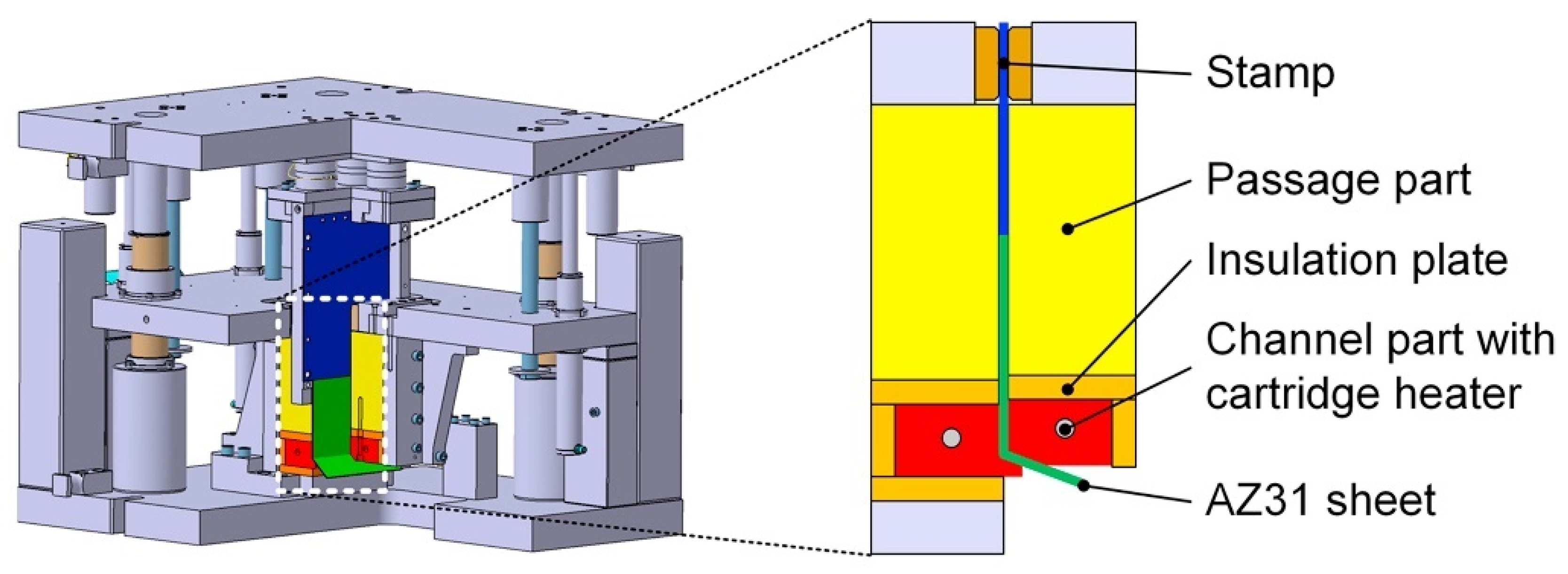

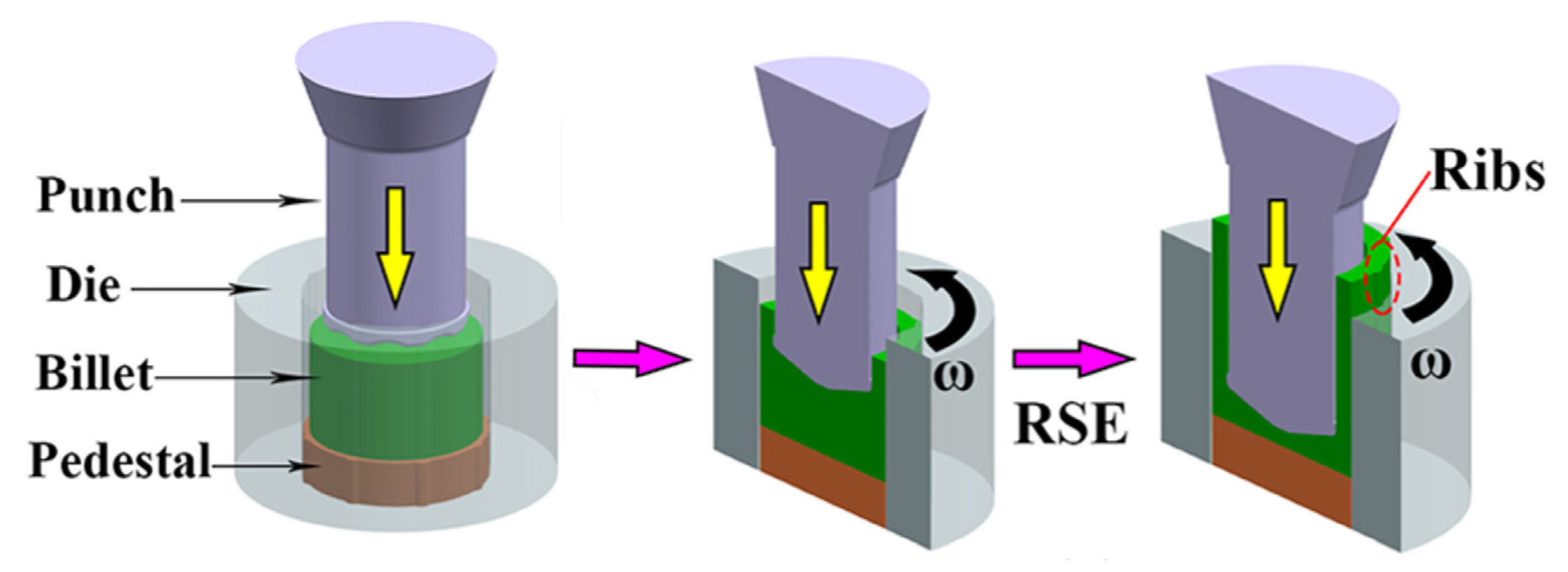

2.4. Rotary Extrusion

3. Effect of Extrusion on Mg Alloys

3.1. Mechanical Properties

3.2. Corrosion Performance

3.3. Corrosion Fatigue Performance

4. Deformation Mechanism of Extrusion

4.1. Slip Deformation

4.2. Twinning Deformation

5. Strengthening Mechanism of Extrusion

5.1. Fine Grain Strengthening and Precipitation Strengthening in DRX Process

5.2. Texture Strengthening

6. Conclusions

- The extrusion process can efficiently refine the grain of Mg alloy and improve its mechanical properties via the grain boundary strengthening mechanism. Moreover, the DRX behavior and texture of Mg alloys during extrusion can significantly improve the properties of alloys. Rare earth Mg alloys generate rare earth texture in the extrusion process, weakening the basal texture strength, and this texture is conducive to the occurrence of basal slip and elongation increase.

- The asymmetry caused by texture hinders the application of Mg alloys in key fields, so it is important to study the relationship between process and texture intensity, non-basal dislocation activation and twin formation.

- The deformation mechanism of magnesium alloy during extrusion is not clear, and the relationships between the dominant position of slip, twins and extrusion conditions needs to be established. In addition, the contribution of slip and twins to deformation has not been evaluated and quantitatively calculated.

- Due to the significant enhancement effect of the extrusion process on magnesium alloys, the extrusion pressure should be reduced in future by combining the optimization of the extrusion process with the setting of die parameters.

- Although the extrusion process enhances the comprehensive mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of alloys, the microstructure of the alloy is still insufficient, which is far from reaching the limit of the properties of magnesium alloy. Energy-field-assisted magnesium alloy extrusion forming, which may involve ultrasound, lasers, or magnetism, could optimize microstructure and promote manufacturing and is one of the potential development directions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xing, F.; Li, S.; Yin, D.D.; Xie, J.C.; Rommens, P.M.; Xiang, Z.; Liu, M.; Ritz, U. Recent progress in Mg-based alloys as a novel bioabsorbable biomaterials for orthopedic applications. J. Magnes. Alloys 2022, 10, 1428–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, M.; Jafari, H.; Singh, R. Effect of extrusion parameters on degradation of magnesium alloys for bioimplant applications: A review. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. 2022, 32, 2787–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Hu, H.J.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, W.; Liang, P.C.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, D.F. An extrusion–shear–expanding process for manufacturing AZ31 magnesium alloy tube. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. 2022, 32, 2569–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.H.; He, X.C.; Dai, Y.B.; Zang, Q.H.; Dong, X.G.; Zhang, Z.Y. Characterization of hot extrusion deformation behavior, texture evolution, and mechanical properties of Mg-5Li-3Sn-2Al-1Zn magnesium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 858, 144136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Z.; Chai, Y.F.; Jiang, B.; Yang, L.X.; Zhang, Y.H.; He, Y.J.; Liang, L.P. Effects of Zn Addition on the Microstructure, Tensile Properties and Formability of As-Extruded Mg-1Sn-0.5Ca Alloy. Metals 2023, 13, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, X.R.; Shao, C.; Zhang, P.; Hu, Z.C.; Liu, H. Effect of Equal Channel Angular Pressing on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of an Mg-5Sn Alloy. Metals 2022, 12, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.H.; Geng, X.; Zhang, X.B. Mechanical and Corrosion Properties of Mg-Gd-Cu-Zr Alloy for Degradable Fracturing Ball Applications. Metals 2023, 13, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.L.; Huo, R.; Tian, Q.W.; Yu, H.; You, B.-S. Dependence of Microstructure, Texture and Tensile Properties on Working Conditions in Indirect-Extruded Mg-6Sn Alloys. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2015, 44, 2132–2137. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.W.; Bian, L.P.; Tian, F.; Han, S.J.; Wang, T.; Liang, W. Microstructural evolution and mechanical response of duplex Mg-Li alloy containing particles during ECAP processing. Mater. Charact. 2022, 188, 111910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.M.; Zhang, Z.M.; Xu, P.; Meng, Y.Z.; Meng, M.; Dong, B.B.; Liu, H.L. Deformation behavior and microstructure evolution of rare earth magnesium alloy during rotary extrusion. Mater. Lett. 2020, 265, 127384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siahsarani, A.; Faraji, G. Hydrostatic cyclic extrusion compression (HCEC) process; a new CEC counterpart for processing long ultrafine-grained metals. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2020, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Liu, W.C.; Zhao, J.; Wu, G.H.; Zhang, H.H.; Ding, W.J. Effect of extrusion ratio on microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-8Li-3Al-2Zn-0.5Y alloy with duplex structure. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 692, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, J.B.; Lee, J.H.; Yu, H.; Park, S.H. Significant improvement in the mechanical properties of an extruded Mg-5Bi alloy through the addition of Al. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 821, 153442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Lin, T.; Meng, H.Y.; Wang, X.T.; Peng, H.; Liu, G.B.; Wei, S.; Lu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, A.Y.; et al. 3D gel-printed porous magnesium scaffold coated with dibasic calcium phosphate dihydrate for bone repair in vivo. J. Orthop. Translat. 2022, 33, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.L.; Wang, S.W.; Wang, Y.Y.; Chen, L.; Yang, L.X.; Xiao, L.; Yang, L.; Hort, N. Mechanical behaviors of extruded Mg alloys with high Gd and Nd content. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2021, 31, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, A.; Du, W.B.; Yu, Z.J.; Ding, N.; Fu, J.J.; Lou, F.; Liu, K.; Li, S.B. Effects of grain refinement and precipitate strengthening on mechanical properties of double-extruded Mg-12Gd-2Er-0.4Zr alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 898, 162873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolpak, F.; Schulze, A.; Dahnke, C.; Tekkaya, A.E. Predicting weld-quality in direct hot extrusion of aluminium chips. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2019, 274, 116294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Yu, Y.; Chen, W.Z.; Zhang, X.R.; Fang, D.Q.; Zhang, W.C.; Wang, W.K. Formation mechanism of <0001> texture connected with excellent ductility during hot extrusion in Mg-9Gd-5Y-0.5Zr alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 859, 144193. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.Y.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, Y.Z.; Zhang, R.; Qiu, W.; Li, C.; Li, W.; Chen, J. In-situ EBSD analysis of microstructural evolution and damage behavior of Mg-Al-Ca-Mn alloys with different extrusion ratios. Mater. Charact. 2023, 199, 112781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.W.; Yuan, K.Z.; Li, X.; Qiao, Y. Microstructure and properties of biomedical Mg-Zn-Ca alloy at different extrusion temperatures. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 105578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Bian, N.; Du, H.Q.; Huo, P.D. Mechanism of plasticity enhancement of AZ31B magnesium alloy sheet by accumulative alternating back extrusion. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, S.M.; Zarei-Hanzaki, A. Accumulative back extrusion (ABE) processing as a novel bulk deformation method. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 504, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.C.; Le, Q.C.; Zhou, W.Y.; Liao, Q.Y.; Zhu, Y.T.; Li, D.D.; Wang, P. Simulation study on microstructure evolution during the backward extrusion process of magnesium alloy wheel. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 105480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatermashhadi, V.; Manafi, B.; Abrinia, K.; Faraji, G.; Sanei, M. Development of a novel method for the backward extrusion. Mater. Des. 2014, 62, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.; Victoria-Hernández, J.; Letzig, D.; Golle, R.; Volk, W. Effect of processing route on texture and cold formability of AZ31 Mg alloy sheets processed by ECAP. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 669, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwahashi, Y.; Wang, J.T.; Horita, Z.; Nemoto, M.I.; Langdon, T.G. Principle of equal-channel angular pressing for the processing of ultra-fine grained materials. Scr. Mater. 1996, 35, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, C.; Ju, J.; Wang, G.W.; Jiang, J.H.; Ma, A.B.; Bai, J.; Xue, F.; Xin, Y.C. Anisotropy investigation of an ECAP-processed Mg-Al-Ca-Mn alloy with synergistically enhanced mechanical properties and corrosion resistance. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 911, 165046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Zhang, Z.M.; Li, G.J.; Xue, Y.; Xu, J. Evolution of the microstructure, texture and mechanical properties of ZK60 alloy during processing by rotating shear extrusion. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 877, 160229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.M.; Zhang, Z.M.; Wang, Q.; Hao, H.Y.; Cui, J.Y.; Li, L.L. Rotary extrusion as a novel severe plastic deformation method for cylindrical tubes. Mater. Lett. 2018, 215, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhilyaev, A.P.; Langdon, T.G. Using high-pressure torsion for metal processing: Fundamentals and applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2008, 53, 893–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.C.; Meng, X.C.; Li, Y.C.; Li, Y.L.; Wan, L.; Huang, Y.X. Friction stir extrusion for fabricating Mg-RE alloys with high strength and ductility. Mater. Lett. 2021, 289, 129414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, S.; Overman, N.; Joshi, V.; Varga, T.; Graff, D.; Lavender, C. Magnesium alloy ZK60 tubing made by shear assisted processing and extrusion (ShAPE). Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 755, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Wang, Q.; Dong, B.B.; Meng, M.; Gao, Z.; Liu, K.; Ma, J.; Yang, F.L.; Zhang, Z.M. The evolution of microstructure and texture of AZ80 Mg alloy cup-shaped pieces processed by rotating backward extrusion. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 1677–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Li, L.; Wen, Z.Z.; Liu, C.R.; Zhou, W.; Bai, X.; Zhong, H.L. Effects of extrusion ratio and temperature on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-Zn-Yb-Zr extrusion alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 833, 142521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Yang, G.Y.; Pei, R.S.; Zhen, Z.L.; Jie, W.Q. Effects of extrusion ratio and subsequent heat treatment on the tension-compression yield asymmetry of Mg-4.58Zn-2.6Gd-0.18Zr alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 810, 141021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Wang, Y.W.; Nazeer, F. The development of a strong and ductile Mg-Zn-Zr thin sheet through nano precipitates and pre-induced dislocation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 817, 141339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Yu, Q.; Jiang, Y.Y. Deformation of extruded ZK60 magnesium alloy under uniaxial loading in different material orientations. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 710, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.J.; Liu, C.M.; Jiang, S.N.; Wan, Y.C.; Chen, Z.Y. Microstructure, mechanical properties and damping capacity of as-extruded Mg-1.5Gd alloys containing rare-earth textures. Mater. Charact. 2022, 189, 111969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.F.; Wang, N.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.M.; Qin, H.; Kong, S.; Bai, T.; Lu, W.J.; Xiao, L.; Ma, X.K.; et al. Texture, microstructure and mechanical properties of an extruded Mg-10Gd-1Zn-0.4Zr alloy: Role of microstructure prior to extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 849, 143476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, F.; Lin, J.X.; Vahid, A.; Munir, K.; Wen, C.; Li, Y.C. Mechanical and corrosion properties of extruded Mg-Zr-Sr alloys for biodegradable implant applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 831, 142192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.Z.; Li, J.Y.; Qi, M.F.; Guo, W.H.; Deng, Y. A newly developed Mg-Zn-Gd-Mn-Sr alloy for degradable implant applications: Influence of extrusion temperature on microstructure, mechanical properties and in vitro corrosion behavior. Mater. Charact. 2022, 188, 111867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, Y.M.; Bae, J.H.; Joo, S.-H.; Park, S.H. Microstructural characteristics and low-cycle fatigue properties of AZ91 and AZ91-Ca-Y alloys extruded at different temperatures. J. Magnes. Alloys 2022, 11, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Yang, Y.; Sun, L.; Liu, J.W.; Deng, H.J.; Wen, C.; Wei, G.B.; Jiang, B.; Peng, X.D.; Pan, F.S. Tailoring the microstructure, mechanical properties and damping capacities of Mg-4Li-3Al-0.3Mn alloy via hot extrusion. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 4197–4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.W.; Pan, F.S.; Jiang, B.; Zeng, Y. Evolution of microstructure and mechanical properties of a duplex Mg–Li alloy under extrusion with an increasing ratio. Mater. Des. 2014, 57, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.S.; Jiang, B.; Zhou, G.Y.; He, J.J.; Pan, F.S. Enhancing strength and ductility of AZ31 magnesium alloy sheets by the trapezoid extrusion. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2014, 30, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.B.; Wang, Z.Z.; Yuan, G.Y.; Xue, Y.J. Improvement of mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of biodegradable Mg-Nd-Zn-Zr alloys by double extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2012, 177, 1113–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.F.; Xu, C.X.; Zhang, Z.W.; Yang, W.F.; Zhang, J.S. Microstructure evolution, strengthening mechanisms and deformation behavior of high-ductility Mg−3Zn−1Y−1Mn alloy at different extrusion temperatures. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. 2023, 33, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Peng, P.; Yang, Q.S.; Luo, A.A. Bimodal grain structure formation and strengthening mechanisms in Mg-Mn-Al-Ca extrusion alloys. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.H.; Bao, J.X.; Qiao, M.L.; Yin, S.Q.; Wang, Z.K.; Cui, J.Z.; Zhang, Z.Q. Microstructures and mechanical properties of Mg–6Zn-1Y-0.85Zr alloy prepared at different extrusion temperatures and speeds. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 21, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.J.; Liu, C.M.; Jiang, S.N.; Gao, Y.H.; Wan, Y.C.; Chen, Z.Y. Tailoring good combinations among strength, ductility and damping capacity in a novel Mg-1.5Gd-1Zn damping alloy via hot extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 871, 144827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.J.; Liu, C.M.; Huang, Y.J.; Jiang, S.N.; Gao, Y.H.; Wan, Y.C.; Chen, Z.Y. Effect of extrusion parameters on microstructure, mechanical properties and damping capacities of Mg-Y-Zn-Zr alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 935, 168122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.S.; Yang, Y.; Hu, J.W.; Su, J.F.; Zhang, X.P.; Peng, X.D. Microstructure and mechanical properties of as-cast and extruded Mg-8Li-1Al-0.5 Sn alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 709, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; She, J.; Yang, Q.S.; Long, S.; Tang, A.T.; Zhang, J.Y.; Dai, Q.W.; Pan, F.S. Bimodal grained Mg–0.5Gd–xMn alloys with high strength and low-cost fabricated by low-temperature extrusion. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 935, 168008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Han, D.S.; Wang, M.C.; Xu, S.; Cai, T.; Yang, S.; Shi, F.J.; Beausir, B.; Toth, L.S. High strength and high ductility of Mg-10Gd-3Y alloy achieved by a novel extrusion-shearing process. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 931, 167498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.D.; Pan, H.C.; Li, J.R.; Xie, D.S.; Zhang, D.P.; Chen, C.J.; Meng, J.; Qin, G.W. Fabrication of exceptionally high-strength Mg-4Sm-0.6 Zn-0.4 Zr alloy via low-temperature extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 833, 142565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.H.; Yang, Q.; Lv, X.L.; Meng, F.Z.; Qiu, X. Effects of reduced extrusion temperature on microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-6Zn-0.5 Zr alloy. Mater. Des. 2023, 225, 111568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.D.; Liu, C.M.; Jiang, S.N.; Gao, Y.H.; Wan, Y.C.; Chen, Z.Y. Effects of extrusion process on microstructure, precipitates and mechanical properties of Mg-Gd-Y-Zr-Ag alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 856, 143990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.Z.; Li, J.L.; Xu, H.B.; Zhao, W.Y.; Zhang, G.L.; Xiao, Y. Evolution of microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-5.9 Zn-1RE-0.6 Zr alloy during extrusion process and aging process. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 34, 105157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.G.; Li, H.R.; Zhao, D.Y.; Dai, Y.Q.; Zhang, J.H.; Zong, J.; Sun, J. High strength commercial AZ91D alloy with a uniformly fine-grained structure processed by conventional extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 780, 139193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Li, S.B.; Yu, Z.J.; Du, B.T.; Liu, K.; Du, W.B. Microstructure and mechanical performance of Mg-Gd-Y-Nd-Zr alloys prepared via pre-annealing, hot extrusion and ageing. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 931, 167476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Bao, J.; Li, Q.N.; Chen, X.Y.; Chen, P.J.; Li, X.Y.; Tan, J.F. Effect of Sm on microstructures and mechanical properties of Mg-Gd (-Sm)-Zr alloys by hot extrusion and aging treatment. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 3877–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Sun, L.; Ke, X.N.; Kong, F.X.; Xie, W.D.; Wei, G.B.; Yang, Y.; Peng, X.D. Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of the Mg-5Al-1Mn-0.5 Zn-xCa alloys prepared by regular extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 858, 144117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.B.; Zhang, Z.M.; Yu, J.M.; Meng, M.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, H.F.; Zhao, X.; Ren, X.W.; Bai, S.B. Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of industrial scale samples of Mg-Gd-Y-Zn-Zr alloy after repetitive upsetting-extrusion process. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 21, 2013–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.M.; Zeng, X.Q.; Peng, L.M.; Gao, X.; Nie, J.F.; Ding, W.J. Microstructure and strengthening mechanism of high strength Mg-10Gd-2Y-0.5 Zr alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2007, 427, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.Y.; Li, G.D.; Zheng, R.X.; Xiao, W.L.; Huang, Y.D.; Hort, N.; Chen, M.F.; Ma, C.L. Reduced yield asymmetry and excellent strength-ductility synergy in Mg-Y-Sm-Zn-Zr alloy via ultra-grain refinement using simple hot extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 856, 143783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Jiang, B.; Kang, Y.H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, W.W.; Zheng, K.H.; Pan, F.S. Tailoring microstructure and texture of Mg-3Al-1Zn alloy sheets through curve extrusion process for achieving low planar anisotropy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 113, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Wang, J.F.; Peng, Y.H.; Dai, C.N.; Pan, Y.L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.Q.; Wang, J.X.; Ma, Y.L.; Pan, F.S. Achieving high strength and rapid degradation in Mg-Gd-Ni alloys by regulating LPSO phase morphology combined with extrusion. J. Magnes. Alloys 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.C.; Xia, Z.H.; Qiao, X.G.; Golovin, I.S.; Zheng, M.Y. Superior ductility Mg-Mn extrusion alloys at room temperature obtained by controlling Mn content. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 869, 144508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.H.; Zhai, H.W.; Wang, L.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, B. A new strong and ductile multicomponent rare-earth free Mg–Bi-based alloy achieved by extrusion and subsequent short-term annealing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 860, 144309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Nakata, T.; Xu, C.; Wang, G.; Geng, L.; Kamado, S. Preparation of high-performance Mg-Gd-Y-Mn-Sc alloy by heat treatment and extrusion. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 934, 167906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cihova, M.; Schäublin, R.; Hauser, L.B.; Gerstl, S.S.A.; Simson, C.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Löffler, J.F. Rational design of a lean magnesium-based alloy with high age-hardening response. Acta Mater. 2018, 158, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.P.; Chen, J.J.; Ma, X.; Liu, W.H.; Xie, H.M.; Li, M.H.; Liu, X. Effects of extrusion speed on the formation of bimodal-grained structure and mechanical properties of a Mg-Gd-based alloy. Mater. Charact. 2022, 189, 111952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Fan, G.H.; Nakata, T.; Liang, X.; Chi, Y.Q.; Qiao, X.G.; Cao, G.J.; Zhang, T.T.; Huang, M.; Miao, K.S.; et al. Deformation behavior of ultra-strong and ductile Mg-Gd-Y-Zn-Zr alloy with bimodal microstructure. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 2018, 49, 1931–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wen, J.B.; Li, H.; He, J.H. Effects of extrusion parameters on the microstructure, corrosion resistance, and mechanical properties of biodegradable Mg-Zn-Gd-Y-Zr alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 891, 161964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.J.; Yu, H.; Zhang, H.X.; Cui, H.W.; Park, S.H.; Zhao, W.M.; You, B.S. Microstructure and mechanical properties of an extruded Mg-8Bi-1Al-1Zn (wt%) alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 690, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.X.; Kim, J.; Liu, T.T.; Tang, A.T.; She, J.; Peng, P.; Pan, F.S. Effects of Mn addition on the microstructures, mechanical properties and work-hardening of Mg-1Sn alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 754, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, J.; Zhou, S.B.; Peng, P.; Tang, A.T.; Wang, Y.; Pan, H.C.; Yang, C.L.; Pan, F.S. Improvement of strength-ductility balance by Mn addition in Mg-Ca extruded alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 772, 138796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, J.; Peng, P.; Xiao, L.; Tang, A.T.; Wang, Y.; Pan, F.S. Development of high strength and ductility in Mg–2Zn extruded alloy by high content Mn-alloying. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 765, 138203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.D.; Zhou, X.J.; Yu, S.L.; Zhang, J.; Lu, X.Z.; Chen, X.M.; Lu, L.W.; Huang, W.Y.; Liu, Y.R. Tensile behavior at various temperatures of the Mg-Gd-Y-Zn-Zr alloys with different initial morphologies of LPSO phases prior to extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 851, 143634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Liu, W.C.; Sun, J.W.; Ding, W.J. Role of extrusion temperature on the microstructure evolution and tensile properties of an ultralight Mg-Li-Zn-Er alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 876, 160181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Leil, T.; Hort, N.; Dietzel, W.; Blawert, C.; Huang, Y.D.; Kainer, K.U.; Rao, K.P. Microstructure and corrosion behavior of Mg-Sn-Ca alloys after extrusion. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. 2009, 19, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Sun, J.W.; Liu, H.J.; Wu, G.H.; Liu, W.C. Microstructure and corrosion behavior of as-homogenized and as-extruded Mg−xLi−3Al−2Zn−0.5Y alloys (x=4, 8, 12). Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. 2022, 32, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazhenov, V.E.; Li, A.V.; Komissarov, A.; Koltygin, A.; Tavolzhanskii, S.A.; Bautin, V.A.; Voropaeva, O.; Mukhametshina, A.M.; Tokar, A. Microstructure and mechanical and corrosion properties of hot-extruded Mg-Zn-Ca-(Mn) biodegradable alloys. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 1428–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.F.; Deng, Y.L.; Guan, L.Q.; Ye, L.Y.; Guo, X.B.; Luo, A. Effect of grain size and crystal orientation on the corrosion behavior of as-extruded Mg-6Gd-2Y-0.2Zr alloy. Corros. Sci. 2020, 164, 108338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, M.; Shi, Z.; Atrens, A.; Furukawa, A.; Kawamura, Y. Influence of crystallographic orientation and Al alloying on the corrosion behaviour of extruded α-Mg/LPSO two-phase Mg-Zn-Y alloys with multimodal microstructure. Corros. Sci. 2022, 200, 110237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.L.; Mishra, R.; Xu, Z.Q. Crystallographic orientation and electrochemical activity of AZ31 Mg alloy. Electrochem. Commun. 2010, 12, 1009–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfpour, M.; Dehghanian, C.; Emamy, M.; Bahmani, A.; Malekan, M.; Saadati, A.; Taghizadeh, M.; Shokouhimehr, M. In- vitro corrosion behavior of the cast and extruded biodegradable Mg-Zn-Cu alloys in simulated body fluid (SBF). J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 2078–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.-M.; Kang, J.S.; Kim, J.C.; Kim, B.; Shin, H.-J.; Park, S.S. Improved corrosion resistance of Mg-8Sn-1Zn-1Al alloy subjected to low-temperature indirect extrusion. Corros. Sci. 2018, 141, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.P.; Xu, F.J.; Deng, K.K.; Han, F.Y.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Gao, R. Effect of extrusion on corrosion properties of Mg-2Ca-χAl (χ = 0, 2, 3, 5) alloys. Corros. Sci. 2017, 127, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, K.; Shi, Y.; Ren, J.P. Effect of extrusion on corrosion behavior and corrosion mechanism of Mg-Y alloy. J. Rare Earths 2016, 34, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlov, D.; Ralston, K.D.; Birbilis, N.; Estrin, Y. Enhanced corrosion resistance of Mg alloy ZK60 after processing by integrated extrusion and equal channel angular pressing. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 6176–6186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.N.; Zhou, W.R.; Zheng, Y.F.; Cheng, Y.H.; Wei, S.C.; Zhong, S.P.; Xi, T.F.; Chen, L.J. Corrosion fatigue behaviors of two biomedical Mg alloys—AZ91D and WE43—In simulated body fluid. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 4605–4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, S.; Raman, R.K.S.; Davies, C.H.J.; Hofstetter, J.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Loeffler, J.F. Stress corrosion cracking and corrosion fatigue characterisation of MgZn1Ca0.3 (ZX10) in a simulated physiological environment. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 65, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.L.; Blawert, C.; Hou, R.Q.; Bohlen, J.; Konchakova, N.; Zheludkevich, M.L. A comprehensive comparison of the corrosion performance, fatigue behavior and mechanical properties of micro-alloyed MgZnCa and MgZnGe alloys. Mater. Des. 2020, 185, 108285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cao, G.S.; Wang, F.; Zhou, L.; Mao, P.L.; Jiang, X.P.; Liu, Z. Investigation of the microstructure and properties of extrusion-shear deformed ZC61 magnesium alloy under high strain rate deformation. Mater. Charact. 2021, 172, 110839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.W.; Oh-Ishi, K.; Kamado, S.; Homma, T. Twins, recrystallization and texture evolution of a Mg-5.99 Zn-1.76 Ca-0.35 Mn (wt.%) alloy during indirect extrusion process. Scr. Mater. 2011, 65, 875–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Q.; Cheng, C.L.; Le, Q.C.; Zhou, X.; Liao, Q.Y.; Chen, X.R.; Jia, Y.H.; Wang, P. Ex-situ EBSD analysis of yield asymmetry, texture and twinning development in Mg-5Li-3Al-2Zn alloy during tensile and compressive deformation. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 805, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbaghian, M.; Mahmudi, R.; Shin, K. Effect of texture and twinning on mechanical properties and corrosion behavior of an extruded biodegradable Mg-4Zn alloy. J. Magnes. Alloys 2019, 7, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.J.; Xu, D.K.; Dong, J.H.; Ke, W. Effect of the crystallographic orientation and twinning on the corrosion resistance of an as-extruded Mg-3Al-1Zn (wt.%) bar. Scr. Mater. 2014, 88, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.W.; Oh-ishi, K.; Kamado, S.; Uchida, F.; Homma, T.; Hono, K. High-strength extruded Mg-Al-Ca-Mn alloy. Scr. Mater. 2011, 65, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.G.; Yan, H.; Chen, R.S. Twinning, recrystallization and texture development during multi-directional impact forging in an AZ61 Mg alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 650, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zeng, X.; Liu, L.; Lu, C.; Zhou, H.; Li, Q.; Zhu, Y. Effects of yttrium on microstructure and mechanical properties of hot-extruded Mg-Zn-Y-Zr alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 373, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Bae, J.H.; Kim, S.-H.; Yoon, J.; You, B.S. Effect of Initial Grain Size on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Extruded Mg-9Al-0.6Zn Alloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2015, 46, 5482–5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadi, S.; Hanna, A.; Azzeddine, H.; Casas, C.; Baudin, T.; Helbert, A.-L.; Brisset, F.; Cabrera, J.M. Characterization of microstructure and texture of binary Mg-Ce alloy processed by equal channel angular pressing. Mater. Charact. 2021, 181, 111454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Jin, S.-C.; Jung, J.-G.; Park, S.H. Influence of undissolved second-phase particles on dynamic recrystallization behavior of Mg-7Sn-1Al-1Zn alloy during low- and high-temperature extrusions. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 71, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.Z.; Nakata, T.; Tang, G.Z.; Xu, C.; Wang, X.J.; Li, X.W.; Qiao, X.G.; Zheng, M.Y.; Geng, L.; Kamado, S.; et al. Effect of forced-air cooling on the microstructure and age-hardening response of extruded Mg-Gd-Y-Zn-Zr alloy full with LPSO lamella. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 73, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Qi, W.J.; Zheng, K.H.; Zhou, N. Enhanced strength and ductility of Mg-Gd-Y-Zr alloys by secondary extrusion. J. Magnes. Alloys 2013, 1, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, N.; Barnett, M.R. The origin of “rare earth” texture development in extruded Mg-based alloys and its effect on tensile ductility. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 496, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, J.D.; Twier, A.M.; Lorimer, G.W.; Rogers, P.D. Effect of extrusion conditions on microstructure, texture, and yield asymmetry in Mg-6Y-7Gd-0.5wt%Zr alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 7247–7256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, J.F.; Huang, S.; Dou, X.X.; Wang, J.X.; Wang, C.L. Formation of an abnormal texture in Mg-Gd-Y-Zn-Mn alloy and its effect on mechanical properties by altering extrusion parameters. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 831, 142270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.J.; Huang, Y.D.; Gan, W.M.; Zhong, Z.Y.; Hort, N.; Meng, J. Effects of extrusion ratio and annealing treatment on the mechanical properties and microstructure of a Mg-11Gd-4.5Y-1Nd-1.5Zn-0.5Zr (wt%) alloy. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 6670–6686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkar, H.; Hoseini, M.; Pekguleryuz, M. Effect of strontium on the texture and mechanical properties of extruded Mg-1%Mn alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 549, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.X.; Jin, L.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Ding, W.J.; Dong, J. Grain growth and texture evolution during annealing in an indirect-extruded Mg-1Gd alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 585, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Choo, H. Influence of texture on Hall–Petch relationships in an Mg alloy. Acta Mater. 2014, 81, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.P.; Zhang, X.M.; Deng, Y.L.; Tang, C.P.; Zhong, Y.Y. Effect of secondary extrusion on the microstructure and mechanical properties of a Mg-RE alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 616, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.Z.; Xu, W.C.; Yang, Z.Z.; Yuan, C.; Shan, D.B.; Teng, B.G.; Jin, B.C. Analysis of abnormal texture formation and strengthening mechanism in an extruded Mg-Gd-Y-Zn-Zr alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 45, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gneiger, S.; Arnoldt, A.; Papenberg, N. Investigations on a ternary Mg-Ca-Si wrought alloy extruded at moderate temperatures. Mater. Lett. 2022, 324, 132633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, G.L.; Wang, Y.S.; Jiang, J.; Gu, J.R.; Li, Y.D.; Chen, T.J.; Ma, Y. Microstructure and mechanical properties of extruded Mg-Y-Zn (Ni) alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 881, 160577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compositions (wt.%) | Extrusion Parameters T, v (mm/s), ER | UTS (MPa) | TYS (MPa) | EL (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg-3.07Al-0.78Zn-0.38Mn | 430 °C, 20, 101:1 | 340.3 | 181.3 | 21.8 | [45] |

| Mg-2.25Nd-0.11Zn-0.43Zr | 290 °C, 50, 8:1 | 247 ± 4.4 | 204 ± 5.3 | 20.6 ± 1.6 | [46] |

| Mg-9Gd-5Y-0.5Zr | 350 °C, 7, 10:1 | 333 | 237 | 31.5 | [18] |

| Mg-3Zn-1Y-1Mn | 360 °C, 1, 16:1 | 243 ± 3 | 177 ± 2 | 19.6 ± 1.2 | [47] |

| Mg-1Mn-0.5Al | 300 °C, 333, 25:1 | 235 | 224 | 35.9 | [48] |

| Mg-6Zn-1Y-0.85Zr | 250 °C, 1, 16:1 | 410 ± 2.8 | 365 ± 3.0 | 7.1 ± 0.6 | [49] |

| Mg-1.5Gd-1Zn | 300 °C, 0.5, 25:1 | 316 ± 2 | 314 ± 1 | 21 ± 0.8 | [50] |

| Mg-3.16Y-1.85Zn-0.37Zr | 360 °C, 0.5, 9:1 | 330 | 280 | 21 | [51] |

| Mg-2Zn-1.6Ca | 400 °C, 3-4, 30:1 | - | 283.47 | 18.08 | [20] |

| Mg-5Li-3Sn-2Al-1Zn | 250 °C, 2 | 270 | 178 | 21.03 | [4] |

| Mg-8Li-1Al-0.5Sn | 260 °C, 25:1 | 322 | 240 | 11 | [52] |

| Mg-0.5Gd | 250 °C, 33.3, 25:1 | 301 ± 2 | 295 ± 2 | 14.9 ± 0.3 | [53] |

| Mg-10Gd-3Y | 400 °C, 22, 4:1 | 249.9 ± 4.8 | 198.1 ± 6.2 | 20.64 ± 3.3 | [54] |

| Mg-4Sm-0.6Zn-0.4Zr | 300 °C, 0.1, 6.25:1 | 435 ± 3 | 430 ± 2 | 6.0 ± 1.2 | [55] |

| Mg-6Zn-0.5Zr | 180 °C, 0.1, 7:1 | 392 | 370 | 13.9 | [56] |

| Mg-7.5Gd-1.5Y-0.4Zr-0.5Ag | 420 °C, 0.2, 9:1 | 329 ± 2 | 239 ± 2 | 15.6 ± 0.4 | [57] |

| Mg-5.9Zn-1RE-0.6Zr | 210 °C, 3, 9:1, 16:1 | 360 | 317 | 13.9 | [58] |

| AZ91D | 240 °C, 0.2, 28:1 | 382 | 320 | 13.8 | [59] |

| Mg-6Gd-3Y-0.5Nd-0.5Zr | 410 °C, 2, 10:1 | 279 | 192 | 24.9 | [60] |

| Mg-6Zn-0.5Zr | 390 °C, 1 | 313 ± 4.6 | 279 ± 4.7 | 12.1 ± 0.4 | [28] |

| Mg-10Gd-3Sm-0.5Zr | 300 °C, 5, 9.67:1 | 345 | 287 | 6.4 | [61] |

| Mg-5Al-1Mn-0.5Zn-0.5Ca | 360 °C, 16, 25:1 | 317 ± 1 | 247 ± 5 | 19.1 ± 0.8 | [62] |

| Mg-9Gd-3Y-2Zn-0.4Zr | 410 °C, 1.2 | 357 | 242 | 9 | [63] |

| Mg-10Gd-2Y-0.5Zr | 350 °C, 9.3:1 | 314 | 232 | 22.9 | [64] |

| Mg-6.91Y-4.21Sm-0.60Zn-0.19Zr | 350 °C, 0.75, 25:1 | - | 369 | 12 | [65] |

| AZ31 | 400 °C, 0.55, 51:1 | 330 ± 5 | 216 ± 5 | 18.9 ± 0.4 | [66] |

| Mg-13.2Gd-4.3Ni | 400 °C | 484 | 334 | 7.4 | [67] |

| Mg-0.4Mn | 150 °C, 0.1, 12:1 | 175 | 128 | 22 | [68] |

| Mg-1Bi-1Mn-1Al-0.5Ca-0.3Zn | 300 °C, 0.5, 20:1 | 438 ± 5.4 | 425 ± 6.8 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | [69] |

| Mg-5.56Zn-1.79Yb-0.31Zr | 320 °C, 0.2, 20:1 | 370 | 259 | 25.9 | [34] |

| Mg-8Gd-4Y-0.5Mn-0.2Sc | 200 °C, 0.1, 10:1 | 380 | 315 | 11 | [70] |

| Mg-0.6Al-0.28Ca-0.25Mn | 350 °C, 0.1, 12:1 | 232 ± 2.7 | 165 ± 7.8 | 14 ± 0.3 | [71] |

| Mg-11Gd-3Y-0.5Nd-Zr | 360 °C, 1, 16:1 | 334 | 256 | 14.9 | [72] |

| Mg-8.2Gd-3.8Y-1.0Zn-0.4Zr | 450 °C, 0.1, 20:1 | 394 ± 1 | 344 ± 1 | 21.5 ± 0.6 | [73] |

| Mg-1.8Zn-1.74Gd-0.5Y-0.4Zr | 340 °C, 6, 12:1 | - | 233.6 | 25 | [74] |

| Mg-8Bi-1Al-1Zn | 300 °C, 1.1, 30:1 | 331 | 291 | 14.6 | [75] |

| Mg-1.11Sn-0.87Mn | 300 °C, 1, 25:1 | 277 | 201 | 14.8 | [76] |

| Mg-1Ca-1Mn | 280 °C, 41.67, 25:1 | 322 | 305 | 18.2 | [77] |

| Mg-2Zn-2Mn | 280 °C, 41.67, 25:1 | 315 | 290 | 24 | [78] |

| Mg-5Gd-3Y-1Zn-0.5Zr | 400 °C, 1, 27:1 | 317 ± 5.3 | 238 ± 0.8 | 7.7 ± 0.9 | [79] |

| Mg-10.22Li-4.73Zn-0.42Er | 150 °C, 25:1 | 272 | 271 | 53.1 | [80] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zheng, X.; Chen, L. Research Progress on Microstructure Evolution and Strengthening-Toughening Mechanism of Mg Alloys by Extrusion. Materials 2023, 16, 3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16103791

Zheng Y, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Tian Y, Zheng X, Chen L. Research Progress on Microstructure Evolution and Strengthening-Toughening Mechanism of Mg Alloys by Extrusion. Materials. 2023; 16(10):3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16103791

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Yaqi, Yuan Zhang, Yun Liu, Yaqiang Tian, Xiaoping Zheng, and Liansheng Chen. 2023. "Research Progress on Microstructure Evolution and Strengthening-Toughening Mechanism of Mg Alloys by Extrusion" Materials 16, no. 10: 3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16103791

APA StyleZheng, Y., Zhang, Y., Liu, Y., Tian, Y., Zheng, X., & Chen, L. (2023). Research Progress on Microstructure Evolution and Strengthening-Toughening Mechanism of Mg Alloys by Extrusion. Materials, 16(10), 3791. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16103791